Refine search

Actions for selected content:

9 results

2 - Employment

-

- Book:

- Stratification Economics and Disability Justice

- Published online:

- 21 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 05 June 2025, pp 52-75

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Fast fashion or clean clothes? Evaluating consumer demand for ethically sourced apparel

-

- Journal:

- Business and Politics / Volume 27 / Issue 2 / June 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 03 April 2025, pp. 309-329

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

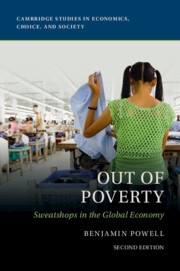

4 - Don’t Cry for Me Kathie Lee

-

- Book:

- Out of Poverty

- Published online:

- 02 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2025, pp 57-69

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Introduction

-

- Book:

- Out of Poverty

- Published online:

- 02 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2025, pp 1-8

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Save the Children?

-

- Book:

- Out of Poverty

- Published online:

- 02 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2025, pp 105-117

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - The Anti-Sweatshop Movement

-

- Book:

- Out of Poverty

- Published online:

- 02 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2025, pp 9-22

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Out of Poverty

- Sweatshops in the Global Economy

-

- Published online:

- 02 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2025

7 - The International Labour Organization

-

- Book:

- International Organizations

- Published online:

- 17 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 159-180

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

26 - Strengthening Labor Rights in the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement: A Lost Opportunity?

-

-

- Book:

- The Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership

- Published online:

- 11 November 2021

- Print publication:

- 02 December 2021, pp 604-632

-

- Chapter

- Export citation