Refine search

Actions for selected content:

39 results

Chapter 29 - Notes on the Aporetics of the One in Greek Neoplatonism

- from Part V - Metaphysics

-

- Book:

- The Ladder of the Sciences in Late Antique Platonism

- Published online:

- 08 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 January 2026, pp 378-385

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 27 - Metaphysical Science (or Theology) in Proclus as Spiritual Exercise

- from Part V - Metaphysics

-

- Book:

- The Ladder of the Sciences in Late Antique Platonism

- Published online:

- 08 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 January 2026, pp 360-369

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

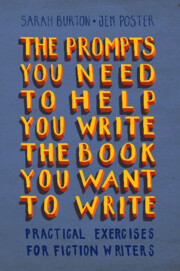

The Prompts You Need to Help You Write the Book You Want to Write

- Practical Exercises for Fiction Writers

-

- Published online:

- 25 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 November 2025

Preface

-

- Book:

- Optimization Models in Electricity Markets

- Published online:

- 09 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 June 2024, pp ix-xiii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

13 - Worked Examples

- from Part V - Supplemental Material

-

- Book:

- Social Inquiry and Bayesian Inference

- Published online:

- 28 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 625-644

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Grammar in Operation

-

- Book:

- Doing English Grammar

- Published online:

- 02 March 2021

- Print publication:

- 11 March 2021, pp 125-146

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part III - Maritime Forces

-

- Book:

- The Culture of Military Organizations

- Published online:

- 05 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2019, pp 319-400

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

14 - The Royal Navy, 1900–1945

- from Part III - Maritime Forces

-

-

- Book:

- The Culture of Military Organizations

- Published online:

- 05 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2019, pp 321-350

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

A Consensus Process on the Use of Exercises and After Action Reports to Assess and Improve Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response

-

- Journal:

- Prehospital and Disaster Medicine / Volume 28 / Issue 3 / June 2013

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 March 2013, pp. 305-308

- Print publication:

- June 2013

-

- Article

- Export citation

Making Exercises More Useful and Relevant Through Application of Modeling and Simuation Technology

-

- Journal:

- Prehospital and Disaster Medicine / Volume 25 / Issue S1 / February 2010

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 June 2012, p. S42

- Print publication:

- February 2010

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Promoting Hospital Preparedness to Chemical Events through Exercises

-

- Journal:

- Prehospital and Disaster Medicine / Volume 25 / Issue S1 / February 2010

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 June 2012, p. S4

- Print publication:

- February 2010

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Community Partnership Development for Emergency Management

-

- Journal:

- Prehospital and Disaster Medicine / Volume 20 / Issue S3 / October 2005

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 June 2012, p. s163

- Print publication:

- October 2005

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Assessment Report on the Amendment of Disaster Medical Services in Japan—What Has Been Changed during the Last 10 Years after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake?

-

- Journal:

- Prehospital and Disaster Medicine / Volume 20 / Issue S2 / June 2005

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 June 2012, pp. S126-S127

- Print publication:

- June 2005

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Applying Management Science to Emergency Medical Planning for Mass-Casualty Incidents in the City of Munich

-

- Journal:

- Prehospital and Disaster Medicine / Volume 20 / Issue S2 / June 2005

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 June 2012, pp. S121-S122

- Print publication:

- June 2005

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Metrics for Measuring Disaster Preparedness

-

- Journal:

- Prehospital and Disaster Medicine / Volume 20 / Issue S1 / April 2005

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 June 2012, p. 71

- Print publication:

- April 2005

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

International Activity of the Council on Cooperation in the Field of Public Health of NIS Countries for Emergencies and Acts of Terrorism Prevention and Relief

-

- Journal:

- Prehospital and Disaster Medicine / Volume 18 / Issue S1 / March 2003

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 17 February 2017, pp. S21-S22

- Print publication:

- March 2003

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

The International Health Specialist Program

-

- Journal:

- Prehospital and Disaster Medicine / Volume 18 / Issue S1 / March 2003

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 17 February 2017, p. S11

- Print publication:

- March 2003

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Terror Australis: Preparedness of Australian Hospitals for Incidents Involving Weapons of Mass Destruction

-

- Journal:

- Prehospital and Disaster Medicine / Volume 17 / Issue S2 / December 2002

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 April 2022, p. S49

- Print publication:

- December 2002

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Review of Disaster Preparedness of Australian Emergency Departments

-

- Journal:

- Prehospital and Disaster Medicine / Volume 17 / Issue S2 / December 2002

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 June 2012, p. S66

- Print publication:

- December 2002

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Disaster Medicine and the Flinders Graduate Entry Medical Program

-

- Journal:

- Prehospital and Disaster Medicine / Volume 17 / Issue S2 / December 2002

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 June 2012, p. S84

- Print publication:

- December 2002

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation