Refine search

Actions for selected content:

69 results

3 - “Find Where Their Women Are”

- from Part I - War in Florida

-

- Book:

- Protecting Women

- Published online:

- 27 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 December 2025, pp 106-142

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 11 - Bloomsbury and Russomania

- from Part II - Global Bloomsbury

-

-

- Book:

- A History of the Bloomsbury Group

- Published online:

- 09 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 23 October 2025, pp 171-186

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 10 - Bloomsbury and the USA

- from Part II - Global Bloomsbury

-

-

- Book:

- A History of the Bloomsbury Group

- Published online:

- 09 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 23 October 2025, pp 155-170

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - The Making of Europe

-

- Book:

- An Economic History of Europe

- Published online:

- 02 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 02 October 2025, pp 15-38

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part VII - Texts from Ibn Khaldūn’s Universal History

-

- Book:

- Ibn Khaldūn: Political Thought

- Published online:

- 14 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 23 January 2025, pp 201-203

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - The European Mythology of the Indies

-

- Book:

- Fallen From Heaven

- Published online:

- 12 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024, pp 173-190

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - The Spanish Civil War and the Legacy of Nineteenth-Century Adventurers

-

- Book:

- Ghosts of International Law

- Published online:

- 12 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024, pp 36-94

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - The European Mythology of the Indies

-

- Book:

- Fallen From Heaven

- Published online:

- 12 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024, pp 225-244

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 14 - What Is Living and What Is Dead in Collingwood’s New Leviathan?

- from Part II - Issues in Collingwood’s Philosophy

-

-

- Book:

- Interpreting R. G. Collingwood

- Published online:

- 22 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 05 December 2024, pp 262-279

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - The Predicament of Civilization

-

-

- Book:

- A History of Haitian Literature

- Published online:

- 07 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 November 2024, pp 158-174

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction to the Second edition

-

- Book:

- Myth and Territory in the Spartan Mediterranean

- Published online:

- 31 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 13 June 2024, pp xxiv-liv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

An Orient of One’s Own: Music and Islamic Modernism in the Late Ottoman Empire

-

- Journal:

- Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle / Volume 54 / April 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 April 2024, pp. 21-36

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

9 - Shelley in the Overgrowth

-

-

- Book:

- Percy Shelley for Our Times

- Published online:

- 07 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 14 March 2024, pp 195-213

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

17 - Civic Signs

- from Part III - Other Signs

-

- Book:

- Chinese Signs

- Published online:

- 29 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 07 March 2024, pp 160-168

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Nations and Nationalisms in the Late Ottoman Empire

- from Part I - Imperial and Postcolonial Settings

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of Nationhood and Nationalism

- Published online:

- 08 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 November 2023, pp 24-42

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Nature and Norms

- from Part II - Thought

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to the Sophists

- Published online:

- 23 December 2023

- Print publication:

- 19 October 2023, pp 157-178

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Rediscovering Moderation in Our Immoderate Age

- from PART II - WHAT KIND OF VIRTUE IS MODERATION?

-

- Book:

- Why Not Moderation?

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 12 October 2023, pp 31-36

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

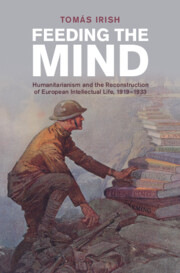

Feeding the Mind

- Humanitarianism and the Reconstruction of European Intellectual Life, 1919–1933

-

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 05 October 2023

1 - 1919

-

- Book:

- Feeding the Mind

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 05 October 2023, pp 17-47

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Feeding the Mind

- Published online:

- 07 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 05 October 2023, pp 1-16

-

- Chapter

- Export citation