Refine search

Actions for selected content:

226 results

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Theatre and Censorship in France from Revolution to Restoration

- Published online:

- 30 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 December 2025, pp 1-24

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 11 - ‘Art Thou Base, Common and Popular?’

- from Part III - ‘One of Us’

-

-

- Book:

- 'The People' and British Literature

- Published online:

- 11 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 December 2025, pp 175-188

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Theatre as Technology

-

- Book:

- Theatre as Technology

- Published online:

- 27 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 December 2025, pp 1-35

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Theatre and Censorship in France from Revolution to Restoration

-

- Published online:

- 30 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 December 2025

Theatre as Technology

- Apparatus, Nostalgia, Obsolescence

-

- Published online:

- 27 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 December 2025

Chapter 3 - Mr Wise and Mr Foolish Go to Town

-

- Book:

- Selling Healing

- Published online:

- 07 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 20 November 2025, pp 47-57

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Sundaris and Jans in the Age of Mechanical Reprodarshan

-

- Book:

- The Archives and Afterlives of Nautch Dancers in India

- Published online:

- 24 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 November 2025, pp 88-133

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Archives and Afterlives of Nautch Dancers in India

-

- Published online:

- 24 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 November 2025

Caryl Churchill's Eco-Socialist Feminism

-

- Published online:

- 07 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 November 2025

-

- Element

- Export citation

English Madrigals on the Jesuit Stage

- Musical Theatre of Martyrdom at the Venerable English College, Rome

-

- Published online:

- 30 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 October 2025

-

- Element

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - Michael Field and Verse Drama

- from Part II - Forms and Genres

-

-

- Book:

- Michael Field in Context

- Published online:

- 03 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 25 September 2025, pp 68-76

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 25 - Late-Victorian Theatre and the New Drama

- from Part IV - ‘Be contemporaneous’

-

-

- Book:

- Michael Field in Context

- Published online:

- 03 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 25 September 2025, pp 230-238

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 35 - Performing Michael Field

- from Part V - Afterlives and Future Fields

-

-

- Book:

- Michael Field in Context

- Published online:

- 03 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 25 September 2025, pp 333-339

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - The Healer and the Witch

- from Part II - The Politics of the Irish Revival

-

-

- Book:

- The Revival in Irish Literature and Culture

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 September 2025, pp 164-181

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 14 - Intermediality

- from Part II - Themes and Issues

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Modernist Theatre

- Published online:

- 28 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp 250-266

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - Philosophy and Theory

- from Part II - Themes and Issues

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Modernist Theatre

- Published online:

- 28 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp 163-179

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Will in English Renaissance Drama

-

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 September 2025

Little Central America, 1984 in Washington, DC, and the Transformative Possibilities of Community-Based Theatre

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Public Humanities / Volume 1 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 August 2025, e126

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Learning in drama

- from Part 2 - What: the arts learning areas

-

- Book:

- Teaching the Arts

- Published online:

- 28 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 August 2025, pp 130-171

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

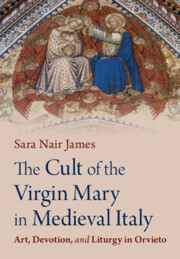

The Cult of the Virgin Mary in Medieval Italy

- Art, Devotion, and Liturgy in Orvieto

-

- Published online:

- 24 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 24 July 2025