Refine search

Actions for selected content:

16 results

Chapter 3 - Counter-Revivals

- from Part I - Revivalism and the Call for Renewal

-

-

- Book:

- The Revival in Irish Literature and Culture

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 September 2025, pp 72-87

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 10 - Sounding Authentic: Renditions of Central and Eastern European Literature by Irish Writers

- from Part III - Missed Translations

-

-

- Book:

- Transnationalism in Irish Literature and Culture

- Published online:

- 13 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 14 November 2024, pp 189-206

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - Learning from Walcott

-

-

- Book:

- Race in Irish Literature and Culture

- Published online:

- 04 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 18 January 2024, pp 190-204

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 15 - Race, Place, and the Grounds of Irish Geopolitics

-

-

- Book:

- Race in Irish Literature and Culture

- Published online:

- 04 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 18 January 2024, pp 302-317

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - ‘The Re-Tuning of the World Itself’: Irish Poetry on the Radio

- from Part II - Infrastructures

-

-

- Book:

- Technology in Irish Literature and Culture

- Published online:

- 19 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 January 2023, pp 118-134

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 11 - Ireland

- from Part II - Nations and Voices

-

-

- Book:

- A History of World War One Poetry

- Published online:

- 18 January 2023

- Print publication:

- 12 January 2023, pp 182-199

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - Irish Nationalism

- from Part II - 1945–1989: New Nations and New Frontiers

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Literature and Politics

- Published online:

- 01 December 2022

- Print publication:

- 15 December 2022, pp 150-164

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

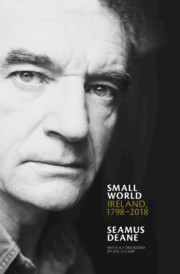

Small World

- Ireland, 1798–2018

-

- Published online:

- 03 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 27 May 2021

Chapter 20 - Classical Roots

- from V - Frameworks

-

-

- Book:

- Seamus Heaney in Context

- Published online:

- 15 March 2021

- Print publication:

- 01 April 2021, pp 221-230

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 17 - Late Style Irish Style

- from Part II - After Parnell

-

-

- Book:

- Parnell and his Times

- Published online:

- 03 December 2020

- Print publication:

- 17 December 2020, pp 294-309

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 12 - Northern Irish Poetry

- from Part Three - Forms and Practices

-

-

- Book:

- The New Irish Studies

- Published online:

- 18 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 24 September 2020, pp 211-227

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 19 - Irish Blockbusters and Literary Stars at the End of the Millennium

- from Part IV - Practices, Institutions, and Audiences

-

-

- Book:

- Irish Literature in Transition: 1980–2020

- Published online:

- 28 February 2020

- Print publication:

- 12 March 2020, pp 360-374

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 14 - Violence, Trauma, Recovery

- from Part III - Forms of Experience

-

-

- Book:

- Irish Literature in Transition: 1980–2020

- Published online:

- 28 February 2020

- Print publication:

- 12 March 2020, pp 263-277

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 12 - Violence, Politics and the Poetry of the Troubles

- from Part III - Sex, Politics and Literary Protest

-

-

- Book:

- Irish Literature in Transition, 1940–1980

- Published online:

- 28 February 2020

- Print publication:

- 12 March 2020, pp 216-232

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Coda: Eavan Boland and Seamus Heaney

- from Part I - Times

-

-

- Book:

- Irish Literature in Transition: 1980–2020

- Published online:

- 28 February 2020

- Print publication:

- 12 March 2020, pp 111-118

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 19 - Curriculum to Canon: Irish Writing and Education

- from Part V - Retrospective Frameworks: Criticism in Transition

-

-

- Book:

- Irish Literature in Transition, 1940–1980

- Published online:

- 28 February 2020

- Print publication:

- 12 March 2020, pp 344-358

-

- Chapter

- Export citation