Refine search

Actions for selected content:

4 results

Epilogue - Staging Libel in Early Stuart England

-

- Book:

- Libels and Theater in Shakespeare's England

- Published online:

- 05 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 19 October 2023, pp 204-213

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Audience

- from Part III - Theater History

-

- Book:

- Entertaining Uncertainty in the Early Modern Theater

- Published online:

- 02 February 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 February 2023, pp 185-217

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Plain Talk

-

- Book:

- The Pursuit of Style in Early Modern Drama

- Published online:

- 26 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 25 August 2022, pp 192-229

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

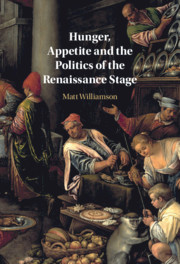

Hunger, Appetite and the Politics of the Renaissance Stage

-

- Published online:

- 28 May 2021

- Print publication:

- 10 June 2021