Refine search

Actions for selected content:

43 results

5 - Stuck

- from Part II - Malta

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 119-148

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 168-175

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Moving On

- from Part II - Malta

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 149-167

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 1-26

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Turbulence at Sea

-

- Book:

- Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023, pp 104-116

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Mobility Economies in Europe's Borderlands

- Migrants' Journeys through Libya and the Mediterranean

-

- Published online:

- 12 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 26 October 2023

19 - Investment Migration and the Importance of Due Diligence

- from Part III - Case Studies and Implications

-

-

- Book:

- Citizenship and Residence Sales

- Published online:

- 06 April 2023

- Print publication:

- 13 April 2023, pp 485-509

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - A Babel and a Gehenna

- from Part II - The Nation

-

- Book:

- Foreign Jack Tars

- Published online:

- 03 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp 83-116

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Local Attitudes towards Postgraduate Psychiatry Training: A Maltese Perspective

-

- Journal:

- European Psychiatry / Volume 65 / Issue S1 / June 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 September 2022, p. S847

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

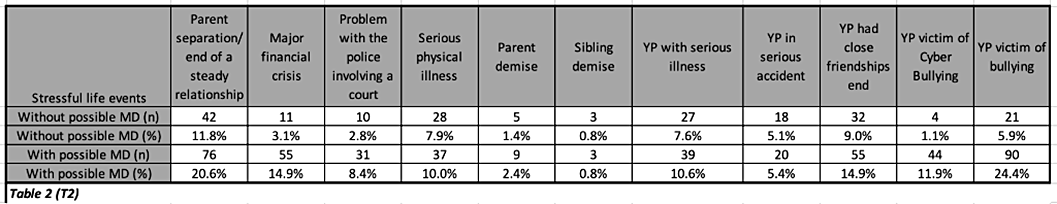

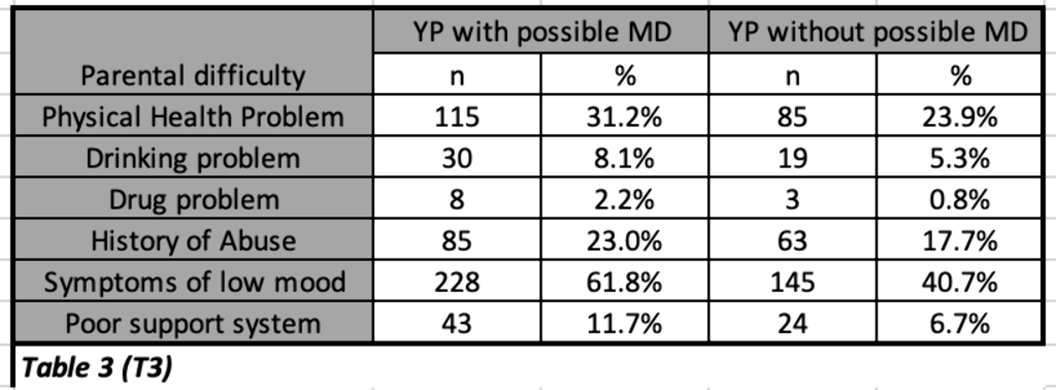

National Study on Mental Health and Emotional Wellbeing among Young People in Malta: Phase 1

-

- Journal:

- European Psychiatry / Volume 65 / Issue S1 / June 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 September 2022, pp. S596-S597

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

A Year of COVID-19 Pandemic Roller-Coaster: The Malta Experience, Lessons Learnt, and the Future

-

- Journal:

- Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness / Volume 17 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 May 2022, e153

-

- Article

- Export citation

11 - Toward Neo-Universalism: Toward a New Reality in International Law?

-

- Book:

- The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

- Published online:

- 17 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 20 May 2021, pp 306-339

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Architecture and the Senses in the Italian Renaissance

- The Varieties of Architectural Experience

-

- Published online:

- 30 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 27 May 2021

5 - Axis Ascendency

-

- Book:

- Strangling the Axis

- Published online:

- 04 June 2020

- Print publication:

- 25 June 2020, pp 107-126

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - The End of the Beginning

-

- Book:

- Strangling the Axis

- Published online:

- 04 June 2020

- Print publication:

- 25 June 2020, pp 127-147

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - The End in North Africa and the Shipping Crisis

-

- Book:

- Strangling the Axis

- Published online:

- 04 June 2020

- Print publication:

- 25 June 2020, pp 148-172

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

4 - Progress

-

- Book:

- Strangling the Axis

- Published online:

- 04 June 2020

- Print publication:

- 25 June 2020, pp 82-106

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Locating the British Mediterranean World

- from Part I - Mediterranean Currents

-

- Book:

- The Yellow Flag

- Published online:

- 27 March 2020

- Print publication:

- 16 April 2020, pp 48-74

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Governing Quarantine

- from Part II - Lazarettos, Health Boards, and the Building of a Biopolity

-

- Book:

- The Yellow Flag

- Published online:

- 27 March 2020

- Print publication:

- 16 April 2020, pp 77-94

-

- Chapter

- Export citation