Refine search

Actions for selected content:

6 results

Chapter 7 - Commentary and Canonisation

- from Part I - 1200–1450

-

-

- Book:

- A History of Poetry in Italy

- Published online:

- 15 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 January 2026, pp 232-265

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

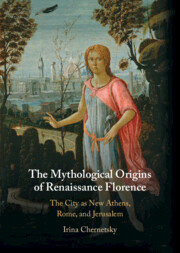

The Mythological Origins of Renaissance Florence

- The City as New Athens, Rome, and Jerusalem

-

- Published online:

- 07 August 2023

- Print publication:

- 13 October 2022

Chapter 16 - Plutarch in the Italian Renaissance

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Plutarch

- Published online:

- 29 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 13 July 2023, pp 323-339

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - The Philosopher, the Humanist, the Translator and the Reader

-

- Book:

- The Vernacular Aristotle

- Published online:

- 10 February 2020

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2020, pp 128-179

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Cantare ad Lyram and Humanist Education

- from Part II - Cantare ad Lyram: The Humanist Tradition

-

- Book:

- Singing to the Lyre in Renaissance Italy

- Published online:

- 31 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 21 November 2019, pp 245-272

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part II - Cantare ad Lyram: The Humanist Tradition

-

- Book:

- Singing to the Lyre in Renaissance Italy

- Published online:

- 31 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 21 November 2019, pp 177-422

-

- Chapter

- Export citation