Refine search

Actions for selected content:

16 results

Chapter 5 - Playgoing, Apprenticeship, and Profit: Francis Quicksilver, Goldsmith, and Richard Meighen, Stationer

- from Part II - Playgoers

-

-

- Book:

- Playing and Playgoing in Early Modern England

- Published online:

- 10 March 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 March 2022, pp 104-121

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - ‘Theatre’ and ‘Play+House’: Naming Spaces in the Time of Shakespeare

- from Part III - Playhouses

-

-

- Book:

- Playing and Playgoing in Early Modern England

- Published online:

- 10 March 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 March 2022, pp 186-204

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Sexual Desire

-

- Book:

- Hunger, Appetite and the Politics of the Renaissance Stage

- Published online:

- 28 May 2021

- Print publication:

- 10 June 2021, pp 100-123

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

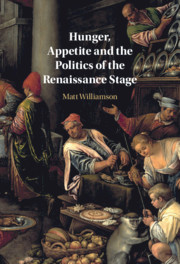

Hunger, Appetite and the Politics of the Renaissance Stage

-

- Published online:

- 28 May 2021

- Print publication:

- 10 June 2021

Afterword - Re-Making Jonson in the Digital World; or, Jonson, Our Contemporary?

- from Part III - Jonsonian Afterlives

-

-

- Book:

- Ben Jonson and Posterity

- Published online:

- 24 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 241-250

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Anecdotal Jonson

- from Part III - Jonsonian Afterlives

-

-

- Book:

- Ben Jonson and Posterity

- Published online:

- 24 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 149-166

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Jonson’s Ghost and the Restoration Stage

- from Part II - Jonson’s Early Reception

-

-

- Book:

- Ben Jonson and Posterity

- Published online:

- 24 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 105-124

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Popular Jonson

- from Part I - Conceptualizing Jonson

-

-

- Book:

- Ben Jonson and Posterity

- Published online:

- 24 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 25-43

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - Jonson in the Shadows

- from Part III - Jonsonian Afterlives

-

-

- Book:

- Ben Jonson and Posterity

- Published online:

- 24 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 167-192

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Seventeenth-Century Readers of Jonson’s 1616 Works

- from Part II - Jonson’s Early Reception

-

-

- Book:

- Ben Jonson and Posterity

- Published online:

- 24 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 85-104

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Corporeal Jonson

- from Part I - Conceptualizing Jonson

-

-

- Book:

- Ben Jonson and Posterity

- Published online:

- 24 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 63-82

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - Adapting Jonson: Three Twentieth-Century Volpones

- from Part III - Jonsonian Afterlives

-

-

- Book:

- Ben Jonson and Posterity

- Published online:

- 24 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 193-213

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Pedantic Jonson

- from Part I - Conceptualizing Jonson

-

-

- Book:

- Ben Jonson and Posterity

- Published online:

- 24 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 44-62

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - Jonson and the Friends of Liberty

- from Part II - Jonson’s Early Reception

-

-

- Book:

- Ben Jonson and Posterity

- Published online:

- 24 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 125-146

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 10 - Jonson and Modern Memory

- from Part III - Jonsonian Afterlives

-

-

- Book:

- Ben Jonson and Posterity

- Published online:

- 24 September 2020

- Print publication:

- 08 October 2020, pp 214-240

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - The Art of Early Modern Cookery

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Food

- Published online:

- 17 March 2020

- Print publication:

- 19 March 2020, pp 29-43

-

- Chapter

- Export citation