Refine search

Actions for selected content:

7 results

Chapter 1 - Bodies

- from Part I - Dramatic Action

-

- Book:

- Entertaining Uncertainty in the Early Modern Theater

- Published online:

- 02 February 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 February 2023, pp 35-70

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter Eight - Of Webs and Wonder

- from Part III - Literature

-

-

- Book:

- Margaret Cavendish

- Published online:

- 28 April 2022

- Print publication:

- 12 May 2022, pp 129-143

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - “Imagination helps me”

-

- Book:

- Cognition and Girlhood in Shakespeare's World

- Published online:

- 24 June 2021

- Print publication:

- 15 July 2021, pp 65-104

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

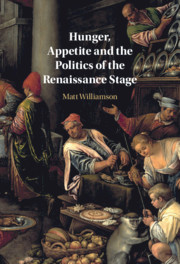

Hunger, Appetite and the Politics of the Renaissance Stage

-

- Published online:

- 28 May 2021

- Print publication:

- 10 June 2021

Chapter 8 - ‘The old name is fresh about me’

- from Part II - The Jacobean Tradition

-

-

- Book:

- Performances at Court in the Age of Shakespeare

- Published online:

- 31 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 24 October 2019, pp 120-134

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part II - The Jacobean Tradition

-

- Book:

- Performances at Court in the Age of Shakespeare

- Published online:

- 31 October 2019

- Print publication:

- 24 October 2019, pp 77-134

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

18 - The Restoration poetic and dramatic canon

- from LITERARY CANONS

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain

- Published online:

- 28 March 2008

- Print publication:

- 14 November 2002, pp 388-409

-

- Chapter

- Export citation