Refine search

Actions for selected content:

11 results

Prologue

-

- Book:

- Hannibal and Scipio

- Published online:

- 05 September 2024

- Print publication:

- 26 September 2024, pp 1-8

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Prologue

-

- Book:

- Hannibal and Scipio

- Published online:

- 05 September 2024

- Print publication:

- 26 September 2024, pp 1-8

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

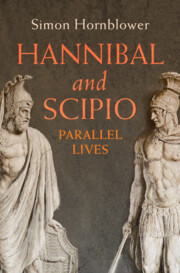

Hannibal and Scipio

- Parallel Lives

-

- Published online:

- 05 September 2024

- Print publication:

- 26 September 2024

Chapter 1 - The Empire Becomes a Body

-

-

- Book:

- Late Hellenistic Greek Literature in Dialogue

- Published online:

- 21 April 2022

- Print publication:

- 05 May 2022, pp 36-68

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Ennius’ Annals as Source and Model for Historical Speech

- from II - Authority

-

-

- Book:

- Ennius' <I>Annals</I>

- Published online:

- 10 April 2020

- Print publication:

- 09 April 2020, pp 147-166

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 34 - Mark Twain Sites

- from Part V - Historical, Creative, and Cultural Legacies

-

-

- Book:

- Mark Twain in Context

- Published online:

- 12 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 02 January 2020, pp 354-362

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Biography

- from Part I - Life

-

-

- Book:

- Mark Twain in Context

- Published online:

- 12 December 2019

- Print publication:

- 02 January 2020, pp 3-13

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Decapitation in Lucan, Statius, and Silius Italicus

-

- Book:

- Abused Bodies in Roman Epic

- Published online:

- 08 July 2019

- Print publication:

- 11 July 2019, pp 67-114

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - Grave Encounters: Silius Italicus’ Punica

-

- Book:

- Abused Bodies in Roman Epic

- Published online:

- 08 July 2019

- Print publication:

- 11 July 2019, pp 241-271

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - The Second Punic War

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Ancient History

- Published online:

- 28 March 2008

- Print publication:

- 07 December 1989, pp 44-80

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - The Carthaginians in Spain

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Ancient History

- Published online:

- 28 March 2008

- Print publication:

- 07 December 1989, pp 17-43

-

- Chapter

- Export citation