Refine search

Actions for selected content:

6 results

Chapter 12 - Assessing Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient: Influence, Genre, and Voice

- from II - People

-

-

- Book:

- Wagner in Context

- Published online:

- 14 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 14 March 2024, pp 122-130

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

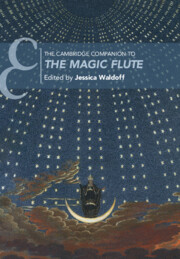

The Cambridge Companion to The Magic Flute

-

- Published online:

- 24 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 02 November 2023

5 - Staging Imperial Identity

-

- Book:

- Music Theatre and the Holy Roman Empire

- Published online:

- 14 June 2022

- Print publication:

- 07 July 2022, pp 218-266

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction: Music for an Imperial Stage

-

- Book:

- Music Theatre and the Holy Roman Empire

- Published online:

- 14 June 2022

- Print publication:

- 07 July 2022, pp 1-41

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - German National Identity and Operatic Italianità

-

-

- Book:

- Italian Opera in Global and Transnational Perspective

- Published online:

- 17 March 2022

- Print publication:

- 24 March 2022, pp 239-260

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 27 - World War I

- from Part V - In History

-

-

- Book:

- Richard Strauss in Context

- Published online:

- 08 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 29 October 2020, pp 247-255

-

- Chapter

- Export citation