Refine search

Actions for selected content:

32 results

Cognition and Conspiracy Theories

-

- Published online:

- 03 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 04 December 2025

-

- Element

- Export citation

Prevalence, nature, and determinants of COVID-19-related conspiracy theories among healthcare workers: a scoping review

-

- Journal:

- European Psychiatry / Volume 68 / Issue 1 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 03 March 2025, e62

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Conspiracy Theories and Religious Worldviews: Unraveling a Complex Relationship

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Conspiracy theory, anti-globalism, and the Freedom Convoy: The Great Reset and conspiracist delegitimation

-

- Journal:

- Review of International Studies , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 January 2025, pp. 1-26

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

13 - Connecting Conspiracy Beliefs and Experiences of Social Exclusion

- from Part III - Topics Related to the Exclusion–Extremism Link

-

-

- Book:

- Exclusion and Extremism

- Published online:

- 16 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 23 May 2024, pp 287-307

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

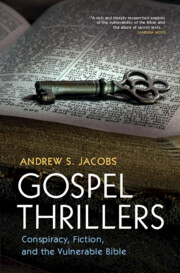

Gospel Thrillers

- Conspiracy, Fiction, and the Vulnerable Bible

-

- Published online:

- 09 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 30 November 2023

Chapter 2 - Down the Conspiracy Theory Rabbit Hole

- from Part II - Recruiting and Maintaining Followers

-

-

- Book:

- The Social Science of QAnon

- Published online:

- 14 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 17-32

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 14 - QAnon, Folklore, and Conspiratorial Consensus

- from Part IV - The Role of Communication in Promoting and Limiting QAnon Support

-

-

- Book:

- The Social Science of QAnon

- Published online:

- 14 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 234-251

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - QAnon in the Year 2020

- from Part III - QAnon and Society

-

-

- Book:

- The Social Science of QAnon

- Published online:

- 14 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 September 2023, pp 123-139

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Normative Inference Tickets

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Perceived expert and laypeople consensus predict belief in local conspiracy theories in a non-WEIRD culture: Evidence from Turkey

-

- Journal:

- Judgment and Decision Making / Volume 18 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 September 2023, e35

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Terrorist Attacks Against COVID-19-Related Targets during the Pandemic Year 2020: A Review of 165 Incidents in the Global Terrorism Database

-

- Journal:

- Prehospital and Disaster Medicine / Volume 38 / Issue 1 / February 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 December 2022, pp. 41-47

- Print publication:

- February 2023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Vaccine hesitancy and conspiracy theories: a Jungian perspective

-

- Journal:

- European Psychiatry / Volume 65 / Issue S1 / June 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 September 2022, p. S502

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

27 - Theories on the Causes of Antisemitism

- from Part III - The Modern Era

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Antisemitism

- Published online:

- 05 May 2022

- Print publication:

- 02 June 2022, pp 497-516

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Coproduction and the crafting of cognitive institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Institutional Economics / Volume 18 / Issue 6 / December 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 March 2022, pp. 961-967

-

- Article

- Export citation

The impact of social desirability bias on conspiracy belief measurement across cultures

-

- Journal:

- Political Science Research and Methods / Volume 11 / Issue 3 / July 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 March 2022, pp. 555-569

-

- Article

- Export citation

Epilogue - Earnest Satire, Cynical Credulity, and the Task of Irony

-

- Book:

- Irony and Earnestness in Eighteenth-Century Literature

- Published online:

- 19 January 2022

- Print publication:

- 27 January 2022, pp 184-189

-

- Chapter

- Export citation