Refine search

Actions for selected content:

58 results

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Irish Romanticism

- Published online:

- 27 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 December 2025, pp 1-25

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Rival institutions: politics, religion, and the jam ʿiyyāt in mid-nineteenth-century Beirut

-

- Journal:

- Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 November 2025, pp. 1-24

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

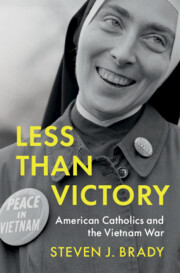

Less Than Victory

- American Catholics and the Vietnam War

-

- Published online:

- 16 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025

Introduction

-

- Book:

- The Humanity of Christ as Instrument of Salvation

- Published online:

- 21 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 04 September 2025, pp 1-12

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

7 - Contact with “Others”

- from Part II - Community Structures

-

- Book:

- Three Consuls

- Published online:

- 31 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 November 2024, pp 183-204

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

L'histoire du christianisme dans la région du Djérid (sud-ouest de la Tunisie)

-

- Journal:

- Libyan Studies / Volume 55 / November 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 19 March 2025, pp. 143-149

- Print publication:

- November 2024

-

- Article

- Export citation

Imperial mission: Jesuits, French diplomacy, and medical education at l’Aurore University in Shanghai, 1912–1952

-

- Journal:

- Medical History / Volume 68 / Issue 2 / April 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 October 2024, pp. 200-216

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

4 - Social Justice through Taxation?

-

-

- Book:

- Social Justice in Twentieth-Century Europe

- Published online:

- 29 February 2024

- Print publication:

- 07 March 2024, pp 78-95

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

No Strings Attached: How Catholic Institutions Prospered at the Expense of the Administrative State and Patient Autonomy

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics / Volume 52 / Issue 1 / Spring 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 31 May 2024, pp. 169-171

- Print publication:

- Spring 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - W. B. Yeats, the Irish Free State, and the Rhetoric of Race Suicide

-

-

- Book:

- Race in Irish Literature and Culture

- Published online:

- 04 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 18 January 2024, pp 143-171

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Protestant Travellers to Rome and the Legacies of the Apostolic Church

- from Part IV - Travelling the World

-

-

- Book:

- Victorian Engagements with the Bible and Antiquity

- Published online:

- 28 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 12 October 2023, pp 211-234

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

-

- Book:

- Beyond the Analogical Imagination

- Published online:

- 28 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 12 October 2023, pp 1-18

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - David Tracy’s Theology-in-Culture

- from Part I - Theology and Culture

-

-

- Book:

- Beyond the Analogical Imagination

- Published online:

- 28 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 12 October 2023, pp 21-40

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 22 - Puccini and Religion

- from Part VI - Puccini through a Political Lens

-

-

- Book:

- Puccini in Context

- Published online:

- 31 August 2023

- Print publication:

- 14 September 2023, pp 181-188

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - The Eighteenth-Century Constitution

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Constitutional History of the United Kingdom

- Published online:

- 12 August 2023

- Print publication:

- 17 August 2023, pp 259-287

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Wards of the State

-

- Book:

- Multiracial Identities in Colonial French Africa

- Published online:

- 25 May 2023

- Print publication:

- 08 June 2023, pp 63-102

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Survival of the Fittest

-

- Book:

- Why Populism?

- Published online:

- 17 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 06 April 2023, pp 163-198

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - ‘A Holy Indifference and Tolerant Favour’

-

- Book:

- Sexual Restraint and Aesthetic Experience in Victorian Literary Decadence

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 09 March 2023, pp 114-144

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - The Catholic Church, ‘Sympathetic’ Priests and Religious Influences on Family Planning Practices after Humanae Vitae

-

- Book:

- Contraception and Modern Ireland

- Published online:

- 16 February 2023

- Print publication:

- 23 February 2023, pp 151-183

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

15 - Natural Law and Human Rights in Catholic Christianity

- from Part III - Natural Law and Human Rights within Religious Traditions

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Handbook of Natural Law and Human Rights

- Published online:

- 03 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 November 2022, pp 218-232

-

- Chapter

- Export citation