Refine search

Actions for selected content:

119 results

Chapter 34 - Felix Mendelssohn’s Posthumous Reception

- from Part VI - Reception and Legacies

-

-

- Book:

- Fanny Hensel and Felix Mendelssohn in Context

- Published online:

- 19 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 January 2026, pp 276-286

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 31 - Interpretations of Jewish Identity

- from Part VI - Reception and Legacies

-

-

- Book:

- Fanny Hensel and Felix Mendelssohn in Context

- Published online:

- 19 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 January 2026, pp 253-259

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bukovina’s Three Stooges of Empire: Nationalism in Central Europe before and after 1918

-

- Journal:

- Central European History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 December 2025, pp. 1-23

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

‘I No Longer Can Say “Never Again”’: A Qualitative Study of the Experiences of Canadian Jewish Older Adults Since the October 7th Attack in Israel

-

- Journal:

- Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue canadienne du vieillissement , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 December 2025, pp. 1-10

-

- Article

- Export citation

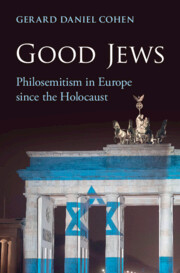

Good Jews

- Philosemitism in Europe since the Holocaust

-

- Published online:

- 19 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 07 August 2025

Chapter 16 - Richard Wagner

- from Part V - Schoenberg’s Others

-

-

- Book:

- Schoenberg in Context

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 04 September 2025, pp 165-173

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 32 - Poetry, Literature and Language

- from Part VIII - Ideas, Beliefs and Interventions

-

-

- Book:

- Schoenberg in Context

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 04 September 2025, pp 316-324

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 28 - Music Criticism and Music Critics

- from Part VII - Performers and Critics

-

-

- Book:

- Schoenberg in Context

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 04 September 2025, pp 276-284

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 29 - Religion

- from Part VIII - Ideas, Beliefs and Interventions

-

-

- Book:

- Schoenberg in Context

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 04 September 2025, pp 287-297

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Mödling

- from Part I - Schoenberg in Place

-

-

- Book:

- Schoenberg in Context

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 04 September 2025, pp 31-38

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - “The Long 1960s” and the Jews (1960–1980)

-

- Book:

- Good Jews

- Published online:

- 19 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 07 August 2025, pp 171-214

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - From Antisemitism to Tactical Philosemitism (1945–1960)

-

- Book:

- Good Jews

- Published online:

- 19 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 07 August 2025, pp 25-59

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

20 - “Judenforschung”: Nazi Jewish Studies

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 16 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 12 June 2025, pp 420-439

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

15 - Hitler and the Nazi Party

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 16 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 12 June 2025, pp 309-327

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - The Holocaust in Eastern European Memory and Politics after the Cold War

- from Part II - Geography

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 16 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 12 June 2025, pp 256-284

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

24 - International Responses to Nazi Race and Jewish Policy, 1933–1939

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 16 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 12 June 2025, pp 502-522

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

10 - Antisemitism in Interwar Europe

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 16 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 12 June 2025, pp 198-219

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - Race-Thinking, Völkisch-Nationalism, and Eugenics

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 16 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 12 June 2025, pp 220-247

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Holocaust Denial and Antisemitism

- from Part I - History

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 16 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 12 June 2025, pp 188-212

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

17 - Antisemitic Policy in the Early Years of the Third Reich

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the Holocaust

- Published online:

- 16 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 12 June 2025, pp 351-372

-

- Chapter

- Export citation