1 Introduction

Through digitalization the reach of formal finance can be expanded to previously underserved territories and populations, thereby enhancing the capacity of financial infrastructures to increase monetary flows. This transformation is observable in developing countries, where various actors collaborate to integrate informal economic activities into financial circuits, trying to connect them to the financialized capitalist system and adapt financial infrastructures. This chapter focuses on the role of philanthrocapitalist actors in this process, specifically examining the efforts of the Mastercard Foundation to advance the digitalization of financial infrastructures around the African agribusiness sector.

Our approach uses both critical development studies and science and technology studies (STS) to investigate infrastructuring processes. Grounded in the insights of Star and Ruhleder (Reference Star and Ruhleder1996), we perceive networking as a pivotal element of infrastructural change, encompassing interconnected social, organizational, and technical dimensions. We study the infrastructural transformation process by analysing the Foundation’s practices in agriculture and digital finance through discourse and programme analysis, as well as by examining its network of partnerships and fundings using social network analysis (SNA).

In keeping with Carse’s historical observation that infrastructure originally pertained to the organizational groundwork that preceded the construction of physical artefacts (Carse, Reference Carse, Harvey, Jensen and Morita2016), we posit that the Foundation contributes to financial infrastructural changes by assembling organizations, technologies, and capital through its networks, thereby creating platforms capable of (re)directing African resource flows into formal finance circuits. Previous research has shown that the Foundation helps to connect digital financial infrastructures to the financialized capitalist economy and that the firm Mastercard is frequently involved in those circuits (Langevin, Brunet-Bélanger, and Lefèvre, Reference Langevin, Brunet-Bélanger, Lefèvre, Chiapello, Engels and Gresse2023). This is not to suggest that these efforts to alter financial infrastructures are guaranteed to succeed; in fact, they encounter various challenges, gaps within existing infrastructures, and complexities in connecting them to peripheral economic elements such as rural finance. Nevertheless, we observe continued digitalization of agricultural finance in which the Foundation is actively involved. Our goal is to understand the project and shed light on the consequences of this process in terms of wealth circulation. We ask: How might the evolution of relationships reshape the credit landscape, impacting accessibility, costs, and organizational channels? We thus aim to contribute to social and policy debates about the power of (digital) financial infrastructures and their agency (Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019; de Goede, Reference de Goede2021; Pinzur, Reference Pinzur2021; Campbell-Verduyn and Hütten, Reference Campbell-Verduyn and Hütten2023).

We begin in Section 2 with our conceptual framework, followed by our methodology. Section 3 delves into the Foundation’s approach and analyses its project related to the emerging digital financial infrastructure in the African agribusiness sector. We then explore the various networks, organizations, and actors involved, and finally, we conclude by reflecting on the connections between this evolving infrastructure and global power structures in the financialized capitalist economy.

2 Philanthrocapitalism and Digital Financial Infrastructures

In a conception akin to an agencement, as described by Callon (Reference Callon2021), Pinzur (this volume) emphasizes, like Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn (Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019), that infrastructures do not inherently exist but instead take shape or materialize through labor that often remains unseen. We specifically argue that the contributions of organizations associated with philanthrocapitalism (or strategic philanthropy) to the emergence and transformation of market infrastructures are overlooked and remain largely imperceptible to analysts in critical development studies and STS. Nevertheless, entities like the Mastercard Foundation are significant actors in the realm of development and the capitalist economy. It is crucial to explore how the practices of these mega-foundations can potentially alter the circulation of wealth as they contribute to transformations such as the creation of new platforms, the digitalization of financial infrastructures, their recombination with other elements, and even the construction of new infrastructures.

Created by Mastercard International, a global payment technology firm that plays a major role in financialized capitalism, the Mastercard Foundation is one of the largest philanthropic institutions in the world in terms of capitalization. It is driven by its mission to advance education and financial inclusion as a catalyst for inclusive growth in developing countries. This raison d’être inherently places the Foundation within the process of financial infrastructures transformation and its digitalization. The critical literature on financial inclusion highlights the pivotal role of digital financial technologies in extending financialization at the margins (e.g., Langevin, Reference Langevin2019; Natile, Reference Natile2020; Bernards, Reference Bernards2022). These mechanisms are vital in establishing financial circuits that link peripheral agricultural markets to the dominant circuits of financialized capitalism. To make payment and credit transactions viable and profitable, operational digital financial infrastructures are essential.

By looking at the prevailing constellation of actors involved in the Foundation’s financial inclusion project and targeting marginal spaces in the global political economy through a neo-colonial analytical lens, we seek to identify the power relations being played out. To do so, we draw upon a broad concept of infrastructures conceived as a background operation and define the financial ‘infrastructuring process’ as an agency process of emerging new capabilities born at the confluence of innovative practical configurations to link, in this case, segments on the periphery of formal economic and financial circuits. This perspective is essential for incorporating infrastructural agency because, as de Goede (Reference de Goede2021, p. 353) contends regarding global payment infrastructures, their inherently political nature holds the potential to ‘reinscribe power relations and reroute money flows’.

The Mastercard Foundation’s existence is intricately linked to global power structures. As part of its 2006 IPO (initial public offering), the firm Mastercard International provided the Foundation with its capital from the firm’s own shares. With a substantial endowment of over $39 billion (Canada Revenue Agency, 2022), the operational capacities of the Foundation are thus partly built on the profitability of the firm Mastercard, a dominant financial capitalism corporation. What Mastercard International does in global capitalism is provide technological financial services to states, consumers, and enterprises to make their financial transactions fluid and secure. Simply put, the business case for the firm is that the higher the volume of transactions through their financial infrastructures, the more user fees are collected. Our previous work revealed that the Foundation’s practices reinforce Mastercard’s global organizational power by helping establish new market infrastructures, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa (Langevin, Brunet-Bélanger, and Lefèvre, Reference Langevin, Brunet-Bélanger, Lefèvre, Chiapello, Engels and Gresse2023). In this chapter, we narrow our focus to agribusiness, a strategically vital area for development institutions, for-profit entities, public entities, and philanthrocapitalist organizations. Globally, the Foundation ranks among the top ten private foundations that invest in agriculture (OECD, 2018, p. 61), with a significant portion of its investment portfolio directed to this sector (OECD, 2023).

The infrastructures discussed in this chapter go beyond being mere physical conduits; they involve farmers who are integrated into the global political economy, albeit through various pathways and socio-technical relations. On a relational level, we aim to differentiate what impacts the potential for inclusion and wealth capture in this infrastructuring process. We explore how new infrastructures emerge and interconnect with existing ones and consider the adaptable nature of the ‘installed base’ (Star, Reference Star1999, p. 382). Socio-technical relations may in fact evolve ‘often subtly – as alternative bundles of sociotechnical relations arise and interact with sociotechnical relations that already exist’ (Campbell-Verduyn and Hütten, Reference Campbell-Verduyn and Hütten2023, p. 461). We put forward the following question: What new relationships between actors and technologies alter the landscape and influence who can access credit, at what cost, and through which organizational channels?

3 Method, Empirical Materials, and Analytical Grid

In Chapter 1 of this volume, the editors Westermeier, Campbell-Verduyn, and Brandl ask contributing authors to adopt an ‘infrastructural gaze’ for their analyses. Although our primary focus is a major player in development finance, we employ a form of ‘infrastructural gazing on finance’ that delves into micro-level empirical data to explore how and where infrastructures undergo change. Our particular interest lies in understanding the actors involved in the Mastercard Foundation’s network and the impact of digitalization on core infrastructure functions like payment and credit in the African rural economy. We examine the Foundation’s role in Africa’s agricultural sector in a relational manner, encompassing relationships with technologies, public and private entities, institutions, investment flows, and other resources within the Foundation’s networks of fundings and partnerships.

Using a database of the Foundation’s discourse on its website from its inception until 2019, we extracted and analysed references related to agricultural finance and the Foundation’s programmes in the African agricultural sector. In addition to examining brief statements such as news items and blog posts, we conducted an in-depth analysis of key documents, particularly those involving the Foundation and its partners in agricultural finance, such as the Fund for Rural Prosperity (FRP) and the Rural and Agricultural Finance Learning Lab (RAFLL). These documents include action plans and assessments regarding agricultural finance and digitalization of the sector. Our objective was to understand the project undertaken by the Foundation in this domain, with a focus on the role of technology in constructing new digital infrastructures or transforming existing ones, along with the (re)integration of certain components.

We combined this method with SNA to examine how actors who play particular roles and mobilize capital are organized and brought into circulation by the Foundation. Our network dataset covers 2,206 fundings granted to 575 organizations from 2007 to 2021. We have also identified 68 partnerships spanning from 2008 to 2022 involving 166 partner organizations. SNA helps us understand the composition and functioning of networks associated with the Mastercard Foundation. It focuses on the structural patterns in relational data, where units (e.g., individuals and organizations) are interconnected within these networks, which is significant for both the unit and the network. This method aligns well with the concept of infrastructure as a relational entity and enables observation of how the Foundation’s practices stimulate network development in various sectors, like agriculture. It sheds light on the process of infrastructural transformation, including its (re)connection to the ‘installed base’. This approach helps us understand the Foundation’s relational capacity in digitalizing and formalizing informal sectors and reshaping markets, without assuming hierarchical control over the entire network or its components.

Our analytical framework, inspired by the ‘infrastructural gaze’, focuses on infrastructure as transformative socio-technical relations. In the discursive aspect, we scrutinize how the Mastercard Foundation defines and characterizes the infrastructuring project by observing their framing of current issues in the African financial sector for agriculture, their action plan, recommendations, the organizational constellation they aim to engage, the mobilizing and transformative roles digital technologies should play in the process, and implications for development circuits and flows. We also examine the diverse networks involved in this infrastructuring project, detailing the organizations participating in the Rural and Agricultural Finance (RAF) initiative and RAFLL, as well as those funded by the Mastercard Foundation, probing their functions and agency in this infrastructural process and potential relationships with power structures and macro-circuits of capital.

4 Agribusiness, Capital, and Technology: A Narrative of Necessity and Innovation

This section examines the Mastercard Foundation’s discourse on its website and in selected reports related to the RAF initiative and RAFLL. The goal is to capture the overall narrative regarding the transformation of financial infrastructure for agribusiness and understand the project promoted by the Foundation and selected partners. This process has been ongoing for about a decade, and the discursive materials, including programme details and sector diagnostics, provide insights into the Foundation’s intentions, practices, and, in some cases, results.

4.1 The Necessary Change

The Foundation’s intent to transform the financial infrastructure for agriculture is based on a diagnosis that positions the African agricultural sector at the heart of the meta-objective ‘inclusive growth’. Reeta Roy, President and CEO of the Mastercard Foundation, explains in this vein that ‘agriculture and agri-business hold tremendous potential to help [people] living in poverty in Africa improve their quality of life and build better futures for their families’ (Mastercard Foundation and One Acre Fund, 2013).

Agriculture is associated with the theme that comes up most often in the Foundation’s discourse, namely employability,1 as the intended effect of its actions: ‘Agriculture, the largest sector of employment in Africa, promises opportunities for job growth and economic prosperity’ (Mastercard Foundation, 2018).

The supply of formal jobs is fundamental to the narrative: poverty exists because there is no job creation. To counter poverty, unemployment must be addressed and, to do so, employment must be created in the formal sectors, mainly in agriculture; otherwise, unemployment and unpaid or poorly paid work persists on family farms and in informal labour. To solve these problems, it is necessary to transform the agricultural sector by intervening in the financial infrastructure to increase access, efficiency, and profitability, among other factors. The quote that follows by an associate programme manager at the Mastercard Foundation summarizes the rationale for infrastructural transformation in agriculture and digital finance in particular:

economic growth in agriculture can be twice as effective in reducing poverty than growth in any other sector. This sounds promising, but the formal sector economy in Africa is not growing fast enough to absorb the 11 million young people entering Africa’s labour market every year. The reality is that agriculture and the informal sector will be the only pathways for the majority of these young people in the next two decades. Transforming agriculture so it is more profitable for young people will be vital. It’s not only a matter of necessity, it’s also a matter of opportunity.

Agriculture in Africa is not yet transformative […] Today’s young people don’t want to be farmers, they want to be ‘digital agripreneurs’. This makes sense if you consider that Africa is increasingly going digital.

4.2 The Programmatic Strategies of Change

The Foundation’s strategy for transforming the agricultural sector and its financial infrastructure involves two key elements. First, it emphasizes empowering youth who play a pivotal role in championing innovative, technology-driven, gender-aware, and climate-smart approaches to modernizing agriculture (Mastercard Foundation, 2018). Secondly, the focus is placed on digital finance to boost financial inclusion among farmers, with the promise of reaching more individuals and fostering inclusive growth in Africa by generating additional economic opportunities. It is generally implied in the Foundation’s discourse that jobs created in agriculture will be formal, yet detailed explanations of the process are lacking. While solutions mainly target mobilizing youth and leveraging digital finance, concrete strategies for transforming the agricultural job market are not clearly outlined. The underlying assumption is that more profitable and efficient agriculture, facilitated by digital finance infrastructure, will lead to the creation of formal jobs. The simplicity of this reasoning is typical of the Foundation’s discourse on socio-economic issues, whether about poverty or job creation (Langevin, Lefèvre, and Brunet-Bélanger, Reference Langevin, Lefèvre, Brunet-Bélanger, Grandvuillemin and Perrin-Joly2024).

Since its creation in 2006, the Foundation has implemented programmes to equip youth with skills in finance and technology, promote entrepreneurship, especially in agriculture, and provide market-oriented training. In 2015, the RAF initiative emerged, encompassing the multi-year (2015–2018) FRP competition and RAFLL. The $50 million FRP has aided 38 companies in creating 171 financial products and services in 15 sub-Saharan African countries (FRP, 2022a). These companies, united by their activity in the financial sector, serve ‘poor, rural, and financially excluded customers’ through various channels (direct banking, input-based finance, asset finance, and tech for access to finance) (FRP, 2022b). In subsequent years, the focus on finance, agriculture, and digital technology among youth persisted, as shown in initiatives like the Young Africa Works summits in 2016 and 2017, which celebrated efforts targeting farmers and supporting various activities in eleven African countries (AgDevCo et al., 2017).

An analysis of the Foundation’s national programmes, constituting its programmatic architecture as of 2022, confirms this orientation. In that year, six out of the seven programmes targeted agriculture as one of their fields of activity: Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, and Uganda. For instance, Kenya’s Young Africa Works programme targets agriculture and the digital economy to catalyse growth. The initiative aims to develop small businesses, enhance productivity in the agricultural value chain, and improve education through digital soft-skills programmes. The narrative strongly emphasizes the digitalization of finance, highlighting the need to expand digital payments for further financial inclusion of rural households. ‘Pathways to Prosperity: 2019 Rural and Agricultural Finance State of the Sector Report’ succinctly summarizes the mechanism: ‘Digitization of payments increases convenience and security of monetary transactions. In addition, it can enable access to other financial products, such as savings and credit, by providing vital customer data to financial service providers’ (ISF and RAFLL, 2019, p. 15).

4.3 The Challenges Encountered

But the success of this mechanism is not a given. Distinct challenges facing the process of digitalizing the agricultural sector are noted in the reports published by the Foundation and ISF Advisors. First, fragmented demand makes participants hard to reach and expensive to serve; a lack of knowledge about market actors fosters distrust. The nature of agricultural interactions, marked by volatility, low transaction values, and localized, seasonal production, discourages financial service provider interest (ISF and RAFLL, 2021, p. 39). Viability and scalability issues arise, given small profit margins and the need for rapid user acquisition with significant capital-intensive investments (ISF and RAFLL, 2021, p. 41). Inefficiencies persist with multiple intermediaries, and limited digital connectivity and physical infrastructures in rural areas pose challenges. Scaling-up digital finance services in agribusiness requires transitioning from early experimentation to reaching a critical mass, necessitating a different stage and type of investment by both service and capital providers to avoid innovation stagnation (ISF and RAFLL, 2019, pp. 7 and 43).

To address these challenges, recommendations include advancing towards a cashless society, urging rural and agricultural economies to embrace digital financial transactions (ISF and RAFLL, 2019, p. 15). The proposed model emphasizes technology-based platformization of agricultural finance, mobile money penetration, and the use of social media for data. Platforms would facilitate direct connections between various value chain actors, enhancing market efficiency and transparency through digitized transaction data (ISF and RAFLL, 2021, p. 15). Special attention to women is advised, considering their higher mobile phone usage and underserved market segment status (ISF and RAFLL, 2019, p. 15). This emphasis is strategic. In a 2021 report on agricultural platforms, ISF and RAFLL cite DigiFarm as a noteworthy example of ‘targeting women’. The case highlights women’s potential as lucrative customer segments ‘with high lifetime customer value. Particularly since Platforms tend to be able to capture more value from offtake-related transactions (services that women may be more likely to use than men) than from other lower margin services such as advisory, or inputs’ (ISF and RAFLL, 2021, pp. 46–47). Finally, reports suggest that another key is an enabling regulatory ecosystem in which to operate. This includes trade policies, foreign exchange management, pricing, and data regulation (ISF and RAFLL, 2021, p. 19).

4.4 Contributing Institutions and Actors

A distinctive feature of the Foundation’s practices is that it works in partnership and involves different types of actors around its initiatives (Lefèvre and Langevin, Reference Lefèvre and Langevin2020). The Foundation does not act independently in the field but instead connects actors to whom it grants financial and sometimes technical resources (see Section 5 for details on this network). The Foundation always calls upon networks of actors. The Digital Financial Services for Agriculture handbook, co-published with the International Finance Corporation (Mastercard Foundation and IFC, 2018), details the roles every type of actor should play to expand the digitalization process from mobile network operators, financial institutions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), or development organizations and agribusinesses to third-party technology providers. In most of the documents analysed, the crucial argument made to justify this relational mode of practice is that partnerships are essential to develop commercial and sustainable digital agricultural financial products and services.

To understand the standard relational modalities in infrastructure transformation, we note that the structuring into networks and platforms between different types of actors is also a hallmark of the model adopted by several of the Foundation’s key partners (especially those who have won FRP challenge grants over the years and make up the RAF initiative portfolio) such as Apollo Agricultulre, APA Insurance, Finserve, and M-KOPA. We can thus conceptualize that those platforms and networks are connected to infrastructures and thereby participate in their transformation.

4.5 The Role of Digital Technologies

The Foundation emphasizes expanding digital technology to reach unbanked, rural, and poor populations, recognizing its role in enhancing financial infrastructure efficiency. Mobile financial technologies, particularly digital payments and mobile money accounts, are crucial for inclusive growth in agriculture to absorb the youth entering the labour market. The concept of the ‘digital farmer’ is evident in the Mastercard Foundation’s statements, reflecting a techno-utopian vision (see, e.g., Mastercard Foundation and KCB Group, 2016). Digital wallets and other technological solutions, such as weather stations and soil sensors, extend beyond finance into the agricultural sector. These transformations converge into digital platforms that organize interactions, streamline communication across the value chain, and generate substantial data that is shared with financial institutions for assessing farmers’ creditworthiness (MastercardFoundation, 2020; ISF and RAFLL, 2021).

4.6 Implications for Circuit/Flux Development

Our examination of the Foundation’s narrative and programmatic materials reveals practices that aim to direct resource flows into the formal economic and finance sector. A key action plan outlines technical recommendations for agribusiness finance growth and defines digitalization, identifying the actors involved and shedding light on flow circulation. Digitalization, as defined by RAFLL, encompasses various aspects, including customer relationship management, registration, loan analysis, disbursement, repayment cash flows, and delivery of support services (Dalberg and RAFLL, 2016, p. 1). We can envision the monetary flows (credit and savings) and who and what will capture a part of the value of this circulation: value created by rural households and the agricultural sector will, in part, be captured by traditional microfinance institutions, agribusiness, and commercial banks, as well as high-tech banks and niche non-banking financial institutions (Dalberg and RAFLL, 2016, p. 2). The promotion of digital platforms by the Foundation and its affiliates encourages both disintermediation and re-intermediation, leading to a transformation of the existing financial circuit (ISF and RAFLL, 2021, p. 49).

Overall, we deduce from this analysis that financial inclusion, digitalization, and the formal economy are at the core of the Foundation’s programmatic strategy. For farmers, the focus is on microfinance, digital finance, and large-scale data collection to understand their behaviour and adapt microfinance and digital finance to this promising market. This strategy contributes to the process of infrastructuring agribusiness by rejigging some infrastructures already in place, sometimes connecting to new ones in a global and digital manner. Like the process highlighted by Plantin et al. (Reference Plantin, Lagoze, Edwards and Sandvig2018) these programmatic orientations point towards processes of ‘platformization’ of infrastructures and an ‘infrastructuralization’ of platforms.

5 Network of Partnerships

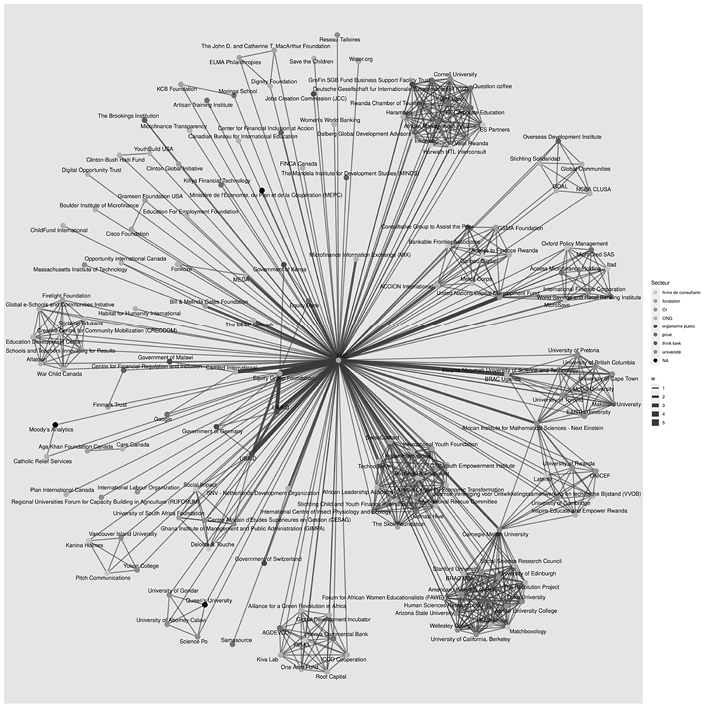

The Foundation’s practices induce the development of new networks around the agricultural sector in Africa, overlapping public and private components. We now turn our attention to the relational changes at the infrastructural level by unpacking the components and connections in these networks. Thus, networking conceived as the core infrastructural change ‘becomes a primary analytic phenomenon’ (Star and Ruhleder, Reference Star and Ruhleder1996, p. 113). Figure 26.12 maps the partnership network surrounding the Foundation since its launch. The mapping exposes partnership clusters in specific sectors with different kinds of actors and organizations, such as in education, the public domain, private consultancy firms, think tanks, NGOs, and private corporations. We noticed a myriad of key actors in the field of financial inclusion, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, USAID (United States Agency for International Development), Women World Banking, Grameen, CGAP (Consultative Group to Assist the Poorest), GSMA (Global System for Mobile Communications Association) Foundation, SEEP (Small Enterprise Evaluation Project) Network, UNCDF (United Nations Capital Development Fund), and Accion. Notably, the Foundation’s initiatives connect influential players on the African continent, tied to colonial power structures, to foster the digital financial services market for the poor, evident in partnerships with Equity Bank, Equity Group Foundation, and the Kenya Commercial Bank (KCB) (details in Langevin et al., in press).

Figure 26.1 Mastercard Foundation’s Partnership Network, 2007–2021. For a higher-resolution, color version visit: www.cambridge.org/Westermeier

Figure 26.2 Legend. For a higher-resolution, color version visit: www.cambridge.org/Westermeier

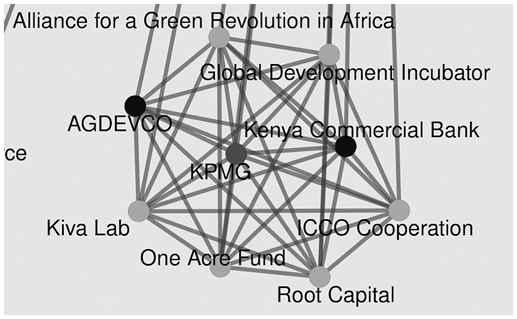

Within this constellation of actors, we focus now more specifically on the RAF initiative (Figure 26.33), which, as noted earlier, involved the Foundation supporting a portfolio of private organizations funded through the FRP. The project was carried out from 2015 to 2019 in collaboration with the RAFLL, an organization created by the Foundation dedicated to learning, best practices, dissemination and mobilization. This trio (RAF, FRP, and RAFLL) collaborates synergistically to disseminate practices across the financial and agricultural sectors, uniting private sector businesses and NGOs (Table 26.1). The budget for this partnership is approximately $148 million.

Figure 26.3 Partnership. For a higher-resolution, color version visit: www.cambridge.org/Westermeier

Table 26.1 The Mastercard Foundation’s Rural and Agricultural Finance Partnerships

| Partner organization | Specific project | Sector | Country | Total funding | Employment ties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KPMG | Mastercard Foundation FRP | Private sector | Kenya | $74,132,092 | 5 |

| ICCO Cooperation | Strengthening African Rural Smallholders | NGO | Netherlands | $28,309,552 | 0 |

| Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa | Financial Inclusion for Smallholder Farmers in Africa Project Support of Farmers and SMEs | NGO | Kenya | $21,211,653 | 0 |

| AGDEVCO | Agricultural Finance for Smallholders and Related Businesses | Private sector | United Kingdom | $17,767,607 | 0 |

| One Acre Fund | Expanding One Acre Fund’s Outreach | NGO | Kenya | $15,442,070 | 0 |

| KCB | Expanding Access to Finance for Smallholder Farmers | Private sector | Kenya | $12,054,328 | 0 |

| Kiva | Expand Financial Access Among African Smallholder Farmers and Rural Populations | NGO | United States | $8,931,909 | 0 |

| Global Development lncubator | Learning Partner: RAFLL | NGO | United States | $8,879,941 | 0 |

| Root Capital | Expanding the Frontier of Rural Agricultural Finance in West Africa | NGO | United States | $7,264,620 | 1 |

KPMG East Africa is the organization which receives the most funding from the Foundation within this partnership, receiving $74 million. The professional services firm manages the FRP. The FRP’s office and phone numbers are the same as KPMG’s offices in Kenya, thus we deduce that the funding is intended for the management of this programme. The Fund’s original aims included improving access to finance for over one million farmers, supporting the commercialization of innovative products and services, and fostering agricultural finance markets. In our analysis of the Foundation’s employment relationships network since its inception, which includes board members and senior and middle management, we identified five connections linking both entities, including current and former COOs of the Foundation.4 These connections are significant, as the Big 4 global professional service firms like KPMG ‘exercise power in the global economy by commanding transnational infrastructures of expertise that provide stability and order to globalization, and which form a critical resource that other actors – namely corporations and regulators – depend on to act’ (Christensen, Reference Christensen2022, p. 1). AgDevCo, a British not-for-profit investment firm specializing in African agribusiness, partnered with the Foundation to enhance productivity and market access for nearly 500,000 smallholder farmers. The KCB collaborated with the Foundation to improve financial service access for up to two million farmers, providing financial and non-financial services through the mobile solution, KCB MobiGrow, with a commitment to make $200 million in credit available (Mastercard Foundation and KCB Group, 2016).

It is worth noting that the private sector partners in this network hold influential positions in the financialized capitalist political economy. KPMG, a major accounting and consulting firm, is part of the elite Big 4, AgDevCo focuses on the African agricultural sector from the United Kingdom, and KCB, known for its connections to neo-colonialism, extends its influence beyond Kenya across the African continent (Bernards, Reference Bernards2022; Langevin et al., in press).

Among NGO partners, ICCO Cooperation (International Cocoa Cooperation) in the Netherlands received over $28 million to offer affordable agricultural financial products to 200,000+ farmers. Kenyan NGO AGRA, founded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation, collaborated with the Foundation to expand financial services access to 700,000 smallholder farmers, emphasizing agribusiness as a primary financing method and supporting agricultural market information systems and payment innovations. One Acre Fund, a Kenyan NGO, provides East African farmers with asset-based financing and agricultural training. US-based NGO Kiva Microfunds, focusing on inclusive finance, established Kiva Labs to provide 700,000 clients access to new financial products.

Global Development Incubator, an American NGO, served as the learning partner for the RAF initiative, overseeing the RAFLL. It shared best practices, improved stakeholder understanding, and developed the monitoring, evaluation, and learning framework for the entire RAF portfolio. The role of this American NGO is an indicator of the significance of the organizational capacity-building and the continuous learning process within infrastructuring seen as a process. Organizational work is a vital aspect of an infrastructural perspective. Carse’s genealogy of the concept notes that, in the early twentieth century, infrastructure ‘referred primarily to the organizational work required before railroad tracks could be laid: either establishing a roadbed of substrate material (literally beneath the tracks) or other work functionally prior to laying tracks like building bridges, embankments, and tunnels’ (Carse, Reference Carse, Harvey, Jensen and Morita2016, p. 28). The Mastercard Foundation’s network-driven transformations empower various actors to document and make visible this learning, accessible through websites like those of the Foundation, RAFLL, and affiliated entities such as Dalberg and ISF, two development consulting firms.

Root Capital, a US-based NGO, engages in social investment in marginalized rural communities. Collaborating with the Foundation on the ‘Expanding the Frontier of Rural Agricultural Finance in West Africa’ initiative, with a budget of approximately $7 million, the partnership aimed to enhance the livelihoods of over 200,000 smallholder farmers. It sought to connect them to local markets, offering access to training and financial services. This collaboration reflects the process of integrating agricultural economies into formal marketplace structures, aligning with Brooks’ (Reference Brooks2021, p. 1) concept of inserting new market subjects ‘into value chains and wider circuits of capital and data’. This aligns with Mann’s (Reference Mann2018, p. 28) observation that digital data in Africa is designed to ‘become a source of power in economic governance’.

From this analysis, we deduce that the majority of these actors are based in the Global North, where innovations are conceived before being implemented in Africa with the support of the Foundation’s capital, expertise, and programmes. These innovations are frequently crafted to integrate new consumers into digital finance platforms assembled in Africa, often through neo-colonial corporate telecommunication, digital, and data infrastructures, enrolling diverse populations previously excluded from formal financial relations under colonial regimes (Langley and Leyshon, Reference Langley and Leyshon2022, p. 401).

6 Conclusion

Our analysis, guided by the infrastructural gaze, has aimed to understand how the infrastructure-(re)building process is linked to existing power dynamics and how it integrates with established circuits, such as those of the Foundation and other key channels in financialized capitalism and the neoliberal development agenda. Discourse analysis reveals an underlying agenda to generate more wealth through inclusive growth, aspiring to establish a commercial agricultural sector fully supported by formal finance and digital technologies. Our SNA indicates that actors involved in (re)building infrastructures and integrating resource flows into channels, whether through activating digital and financial literacy or constructing platforms leveraging massive data of African farmers, all share the characteristic of being anchored in the formal economy and finance.

This study sheds light on the ongoing involvement of philanthrocapitalist organizations in the financial sector in Africa, providing insights into the way financial infrastructures in the developing world are interconnected with global power structures (Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn, Reference Bernards and Campbell-Verduyn2019). Echoing concerns expressed in critical infrastructure literature, we acknowledge how infrastructural technologies ‘inscribe specific ways of doing things [and] sediment historical power relations and core-periphery relations’ (de Goede, Reference de Goede2021, p. 354). This prompts us to question the implications for the future of agribusiness in Africa, considering that the transformed financial infrastructure, through the integration of the Foundation’s networks, assigns pivotal functions to neo-colonial financial institutions like KCB. The financial infrastructure underlying agribusiness in Africa today significantly mirrors the power dynamics of the past. The project that seeks to ‘bank the unbanked’ is being made possible by the transformations of financial and development infrastructures that redistribute financial access while being anchored in powerful existing systems that can capture wealth.