Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about significant changes in various aspects of daily life, leading to an increase in psychological symptoms and a decline in mental health, as well as shifts in alcohol use behaviors (e.g., [Reference Avena, Simkus, Lewandowski, Gold and Potenza1–Reference Qi, Zhang, Robinson, Bobou, Gourlan and Winterer3]). Evidence consistently highlighted a rise in psychological distress, emphasizing the negative impact of the pandemic on well-being and mental health [Reference Thye, Law, Tan, Pusparajah, Ser and Thurairajasingam4].

In contrast, the impact of the pandemic on alcohol consumption has been less clear. It was shown that alcohol use increased (e.g., [Reference Kerr, Ye, Martinez, Karriker-Jaffe, Patterson and Greenfield5, Reference Jackson, Merrill, Stevens, Hayes and White6]), also depending on subgroup-specific aspects such as socio-demographics as well as age (e.g., [Reference Kerr, Ye, Martinez, Karriker-Jaffe, Patterson and Greenfield5]) and with changes in social drinking habits [Reference Jackson, Merrill, Stevens, Hayes and White6], or decreased, potentially due to restricted availability and financial limitations during the pandemic [Reference Rehm, Kilian, Ferreira-Borges, Jernigan, Monteiro and Parry7]. Some studies reported no significant changes in alcohol consumption [Reference Chaffee, Cheng, Couch, Hoeft and Halpern-Felsher8], while others observed a decrease [Reference Roberts, Rogers, Mason, Siriwardena, Hogue and Whitley9]. Given that studies have shown that psychological distress often co-occurs with problematic alcohol consumption [Reference Capasso, Jones, Ali, Foreman, Tozan and DiClemente10, Reference Evans, Alkan, Bhangoo, Tenenbaum and Ng-Knight11] and that social isolation and stress are key factors in disordered drinking [Reference Mangot-Sala, Tran, Smidt and Liefbroer12], there may be a relationship between changes in well-being from pre-pandemic to during the pandemic and shifts in alcohol use behaviors.

This may have already manifested at the very onset of the pandemic, when changes in daily life were most pronounced. Even though the pandemic is now years in the past, its relevance for clinical practice remains evident, particularly the importance of understanding and considering early processing and reactions. These early responses could serve as significant triggers for later reactions and developments, potentially helping to identify subgroups that, due to these initial responses, require different treatment approaches. Such experiences and reactions may persist (e.g., in the form of a generally altered coping style in challenging situations), even if they do not appear to have an immediate impact on the current situation.

Substance use, typically associated with social reinforcement, may shift during crises toward coping mechanisms driven by negative internal states [Reference Conrod, Pihl and Vassileva13, Reference Cooper14]. While the link between psychological symptoms and alcohol consumption is well-established [Reference Li, Wang, Li, Shen, Li and Zhang15, Reference Tran, Hammarberg, Kirkman, Nguyen and Fisher16], the intricate interplay of these factors may evolve due to the unique stressors and uncertainties introduced by the pandemic. This dynamic could have been particularly pronounced during the early phase of the pandemic, when challenges and restrictions in daily life were at their peak. Previous studies that have looked at these early periods of the COVID-19 pandemic have found an increase in depression and anxiety symptoms, sleep, and smoking, as well as increased drinking, to cope with worries [Reference Martínez-Cao, de la Fuente-Tomás, Menéndez-Miranda, Velasco, Zurrón-Madera and García-Álvarez17–Reference Stanton, To, Khalesi, Williams, Alley and Thwaite19].

Examining patterns from this period that extend beyond the well-known core aspects of depression and anxiety to include broader psychological symptoms, as well as their specific interaction with alcohol use and the comorbid presence of elevated symptoms within these spectrums, could offer valuable insights into the trajectories of these behaviors during later stages of the pandemic and the post-pandemic period. Furthermore, it is essential to examine data from an age-relatively homogeneous sample to minimize potential age-related experiential effects. Early adulthood is particularly important in the context of prevention and early intervention.

In the present study, we aimed to investigate the associations between psychological symptoms and alcohol consumption both several years prior to and during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, using a longitudinal approach in individuals in early adulthood. Through the application of group and correlation analyses as well as machine learning, we specifically sought to address the following research questions: 1. Are there differences in the levels of alcohol consumption and psychological symptoms between the pre-pandemic period and the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic? 2. Do the levels of alcohol consumption and psychological symptoms change from the pre-pandemic period to the early phase of the pandemic, and how are these changes related to the association between psychological symptoms and alcohol consumption?

Methods

Data source

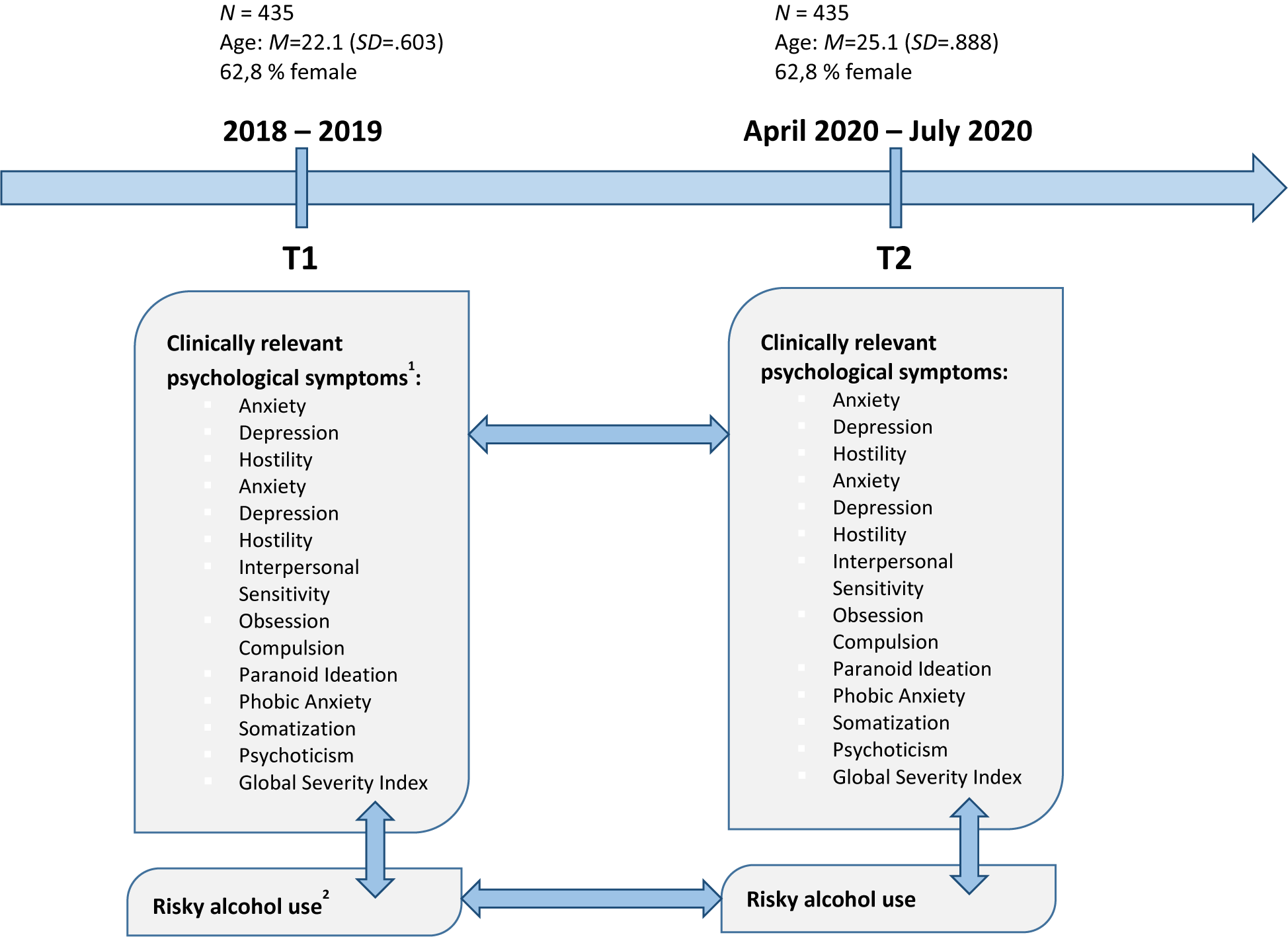

In the present study, we investigated a sample of healthy young adults (N = 435, age range 22–25 years) from the longitudinal Imaging Genetics (IMAGEN) study [Reference Schumann, Loth, Banaschewski, Barbot, Barker and Büchel20]) for whom data pre- and during COVID-19 exist (Figure 1). Young adults were recruited in Germany, Ireland, France, and the United Kingdom through school visits, flyers, and registration offices. Exclusion criteria were serious medical conditions, pregnancy, and previous head trauma with unconsciousness. The COVID assessments were performed in addition to the general longitudinal baseline and follow-up timeline, and participation was voluntary, with only a subset of individuals choosing to take part in this assessment. We included in our analyses only participants with complete data for all required variables (BSI, demographics, and AUDIT) at both measurement timepoints.

Figure 1. Data assessment before (T1, FU3 assessment in Imaging Genetics (IMAGEN)) and during COVID-19 (T2); 1using the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT, total score).

Ethics statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects were approved by the local ethics committees of the recruitment centers. All participants and their guardians provided written or online informed consent prior to participation.

Measures

Assessment of psychological symptoms

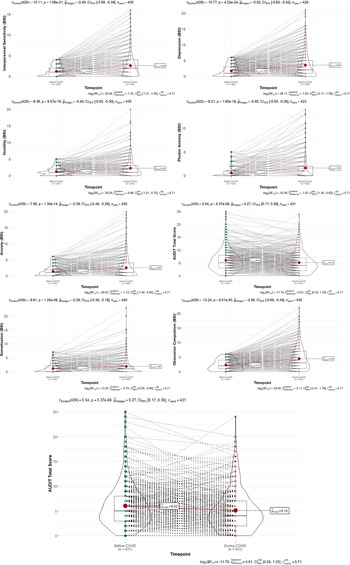

We used the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), which covers nine symptom dimensions (Table 1): somatization, obsession-compulsion, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation and psychoticism, and the global severity index, which represents the sum of those dimensions [Reference Derogatis21].

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alphas for study variables and comparison of mental health pre-pandemic to during the pandemic

Assessment of alcohol consumption

For the assessment of alcohol consumption, we used the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) score for our analyses [Reference Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders and Monteiro22]. The AUDIT Alcohol Assessment is a globally recognized tool designed to evaluate alcohol consumption habits, providing valuable insights into individuals’ drinking patterns and associated risks [Reference Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders and Monteiro22, Reference Saunders, Aasland, Amundsen and Grant23]. It serves as a standard for identifying different levels of alcohol use and the potential for dependency. The AUDIT score (Table 1) comprises nine items that collectively represent an individual’s alcohol consumption behavior. This scoring system allows for a comprehensive evaluation of alcohol use patterns and related behaviors, which provided a valid indicator concerning our research question and, in relation to previous studies, specifically of the IMAGEN cohort, to be able to link the results with the existing knowledge from the studies.

Statistical analysis

The present study aimed to explore the relationship between psychological symptoms and alcohol consumption before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, including the predictive impact of psychological symptoms (using the BSI scales) on alcohol use (using the AUDIT total score). To achieve this, we have employed a series of detailed analyses using R Studio’s ggstatsplot library. We performed correlation analyses to examine the associations between the BSI scales and AUDIT scores separately for the pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19 periods. We conducted paired samples t-tests to assess whether BSI and AUDIT scores have significantly changed pre- versus during COVID-19. We calculated difference scores of BSI and AUDIT score levels pre- versus during COVID-19 for each participant. These difference scores were then used in further analyses to examine if and how the changes in psychological symptoms and alcohol consumption are associated (for distribution plots for both BSI scales and AUDIT scores, see Supplementary Material 1–3). These analyses included correlation analyses as well as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and classification models. This analysis was conducted in two contexts: first, predicting AUDIT scores during COVID-19 using pre-COVID-19 BSI subscales, and second, predicting changes in AUDIT scores (pre- to during-COVID-19) using changes in BSI subscales. Model performance was evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 scores. The SHAP values indicate the relative importance of each feature (BSI scales) in predicting alcohol use (AUDIT scores), both during COVID-19 as well as for the change from pre- to during COVID-19. For the latter one, participants were grouped in alcohol use into three categories, based on their difference scores: increased consumption, decreased consumption, and persistent consumption. SHAP values were used to interpret the impact of each psychological symptom on the likelihood of a participant falling into one of the three alcohol consumption groups (increase, decrease, and persistent). We employed the brute force method to determine the most predictive subset of psychological symptom changes (subscales) for forecasting the level of alcohol use (AUDIT total score) during COVID-19 and the changes from pre- to during COVID-19. This approach systematically evaluates all possible subsets of predictors to determine which combination yields the best model performance. Finally, to also take into account the changes in psychological symptoms pre- versus during COVID-19, we performed a classification model using the difference values of psychological symptoms as predictors and the categorized changes in alcohol consumption (increase, decrease, and persistent) as the target variable. Throughout the analyses, we controlled for covariates including age and center, and, for the change-related associations, also the pre-COVID-19 levels, to account for potential confounding variables and effects. Throughout the analyses, covariates including age, center, and pre-COVID-19 AUDIT levels were included to control for potential confounding effects. A significance threshold of p < .05 was applied for all statistical tests, with corrections for multiple comparisons conducted using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. For all significant findings, effect sizes (e.g., Cohen’s d, r) were calculated to contextualize the magnitude of the effects.

Results

Associations between alcohol consumption and psychological symptoms pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19

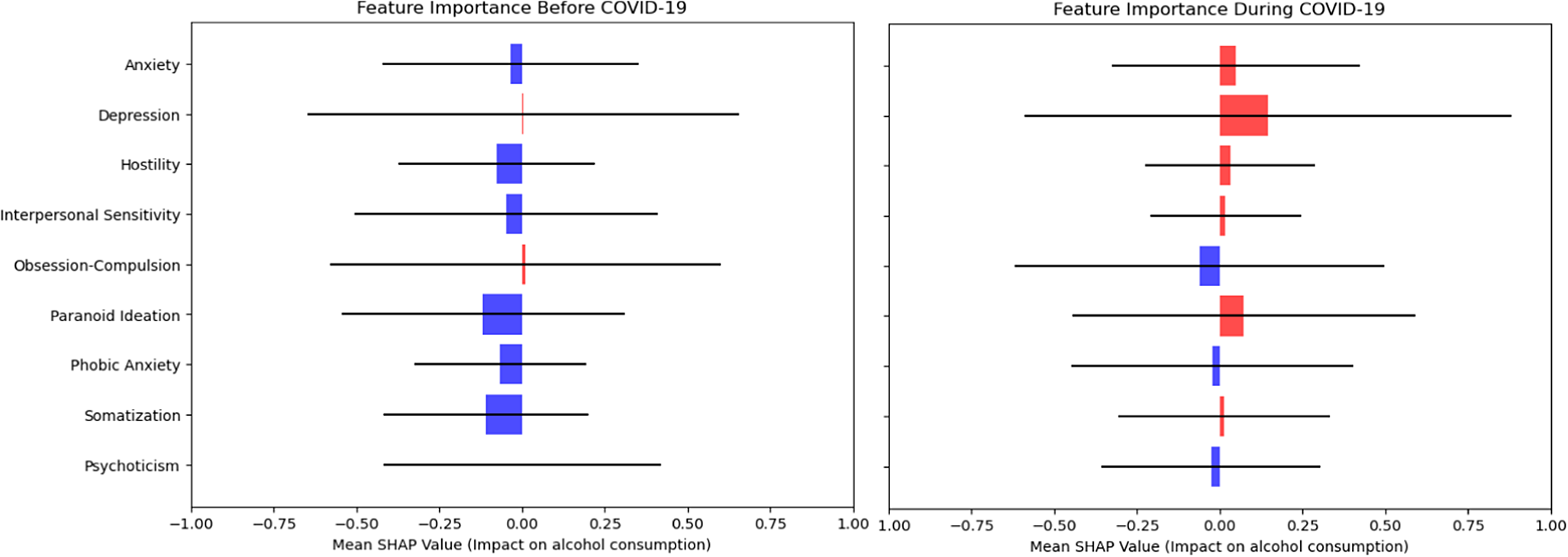

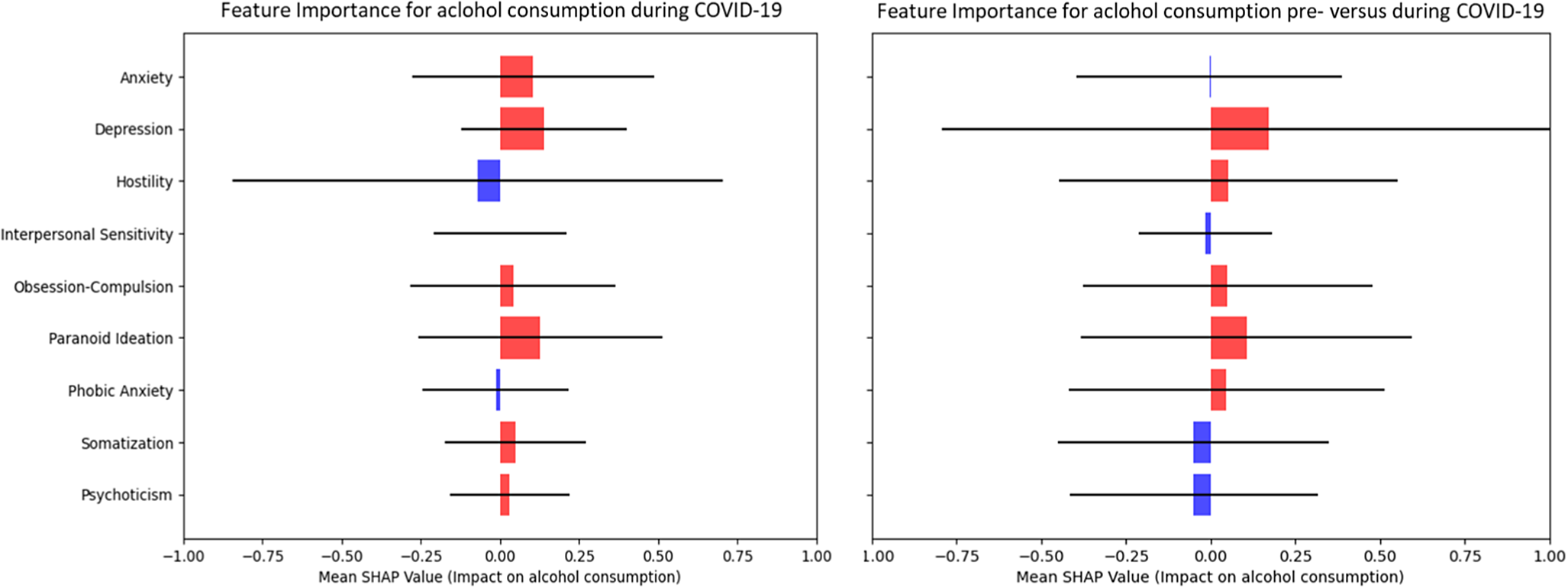

We found a diverse set of significant correlations between several psychological symptoms and alcohol consumption both pre- and during COVID-19. While BSI anxiety (pre: r = 0.102, p = 0.036; during: r = 0.146, p = 0.003) and psychoticism (pre: r = 0.112, p = 0.022; during: r = 0.115, p = 0.019) were significantly positively correlated with alcohol use both pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19, in addition, BSI depression (r = 0.192, p < 0.001), interpersonal sensitivity (r = 0.146, p = 0.003), obsession-compulsion (r = 0.134, p = 0.006), paranoid ideation (r = 0.141, p = 0.004), and the global severity index (r = 0.166, p < 0.001) were all significantly positively correlated with AUDIT scores. The SHAP analyses also showed varied impact of and distinct importance among psychological symptoms on alcohol use pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19 periods (Figure 2). For example, while pre-COVID-19, depression had a minimal influence on alcohol use (SHAP value of 0.00040), during COVID-19, depression emerged as the most influential factor, with a mean SHAP value of 0.1463.

Figure 2. SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values for psychological symptoms predicting alcohol use pre- and during COVID-19.

The SHAP values represent the relative importance of each psychological symptom (BSI subscale) in predicting AUDIT scores. Positive SHAP values (in red) indicate that higher symptom levels increase the likelihood of higher alcohol use (AUDIT scores), while negative SHAP values (in blue) indicate the opposite effect. Horizontal bars reflect the variability of SHAP values across participants, providing insight into the consistency of each symptom’s contribution to model predictions. The mean SHAP values, shown as points, summarize the overall contribution of each symptom. It is important to note that SHAP values are not statistical confidence intervals but rather describe the magnitude of feature importance in the model.

Changes of levels of alcohol consumption and psychological symptoms from pre-COVID-19 to during COVID-19 and their associations

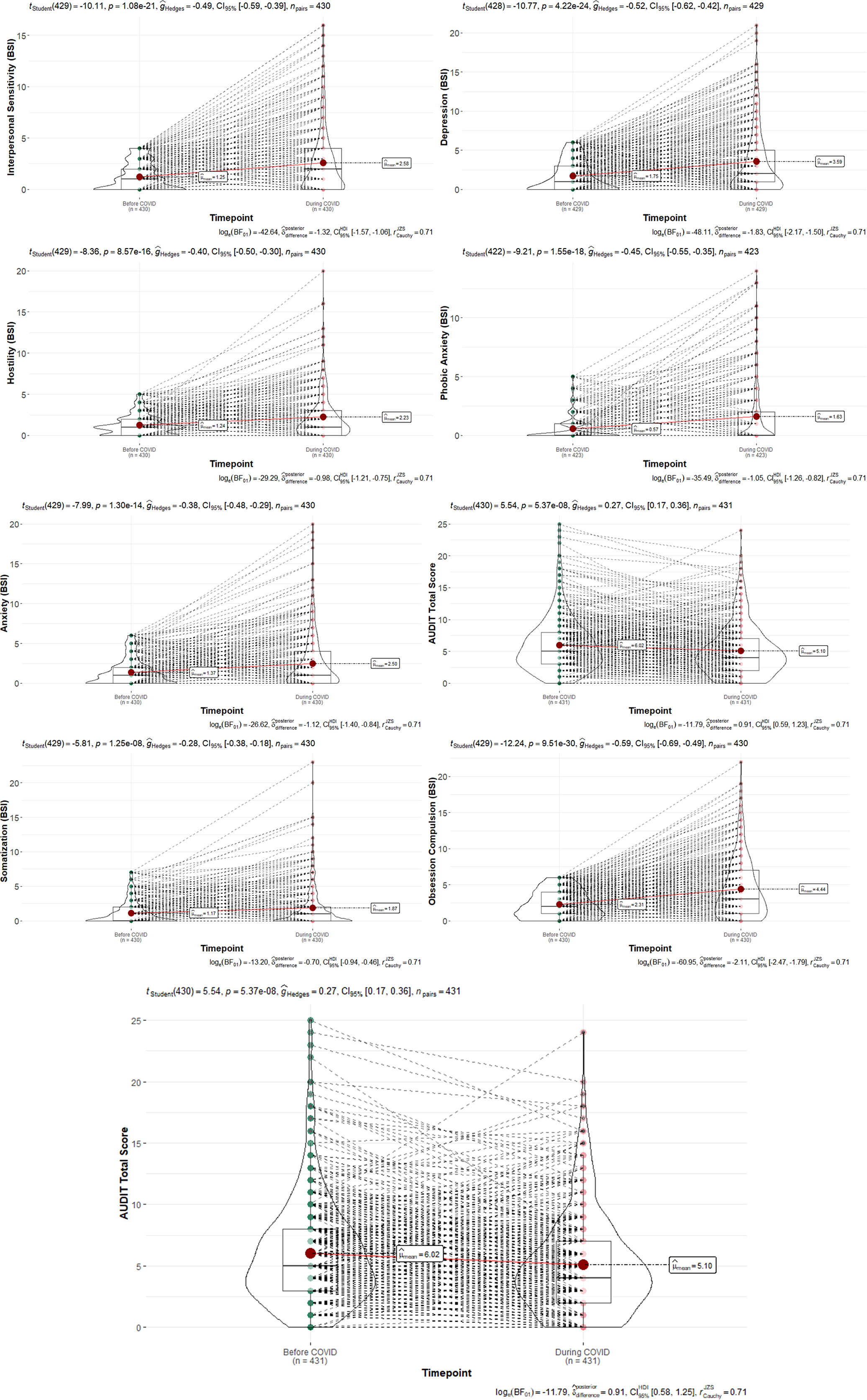

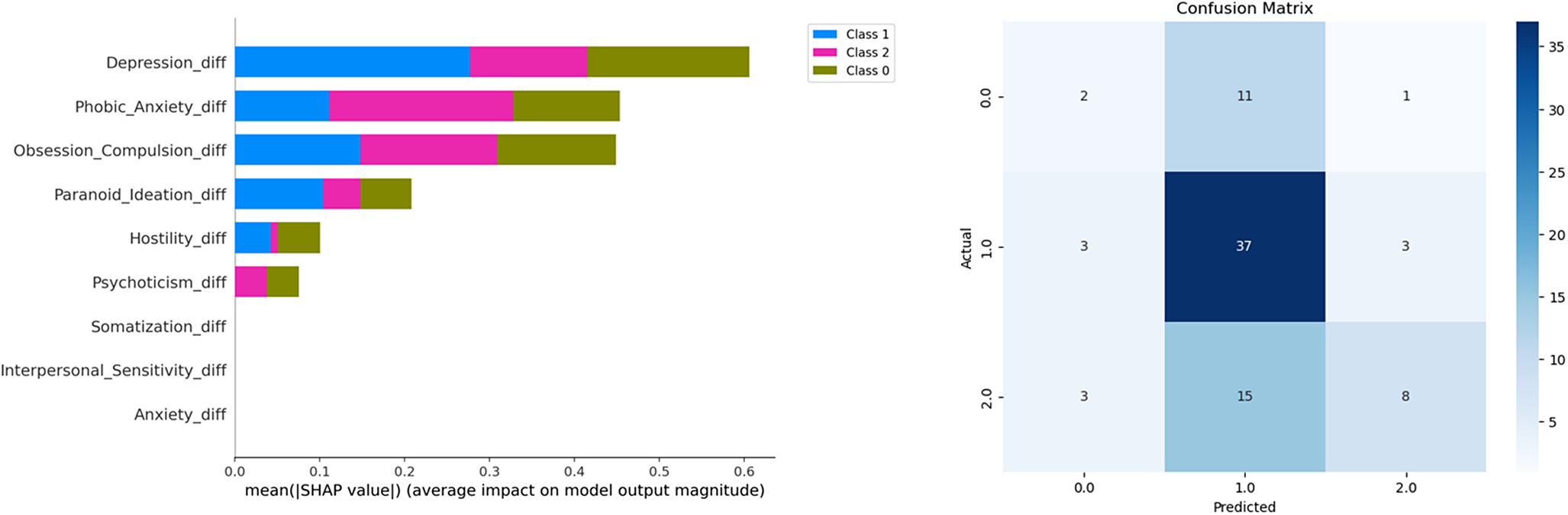

For pre-compared during COVID-19, we found significant differences for both the AUDIT scores and the BSI scales (Figure 3). Participants showed significantly higher levels in all BSI scales and significantly lower levels in the AUDIT total score during versus pre-COVID-19 (Table 2).

Figure 3. Changes in BSI scales and AUDIT scores from pre- to during COVID-19.

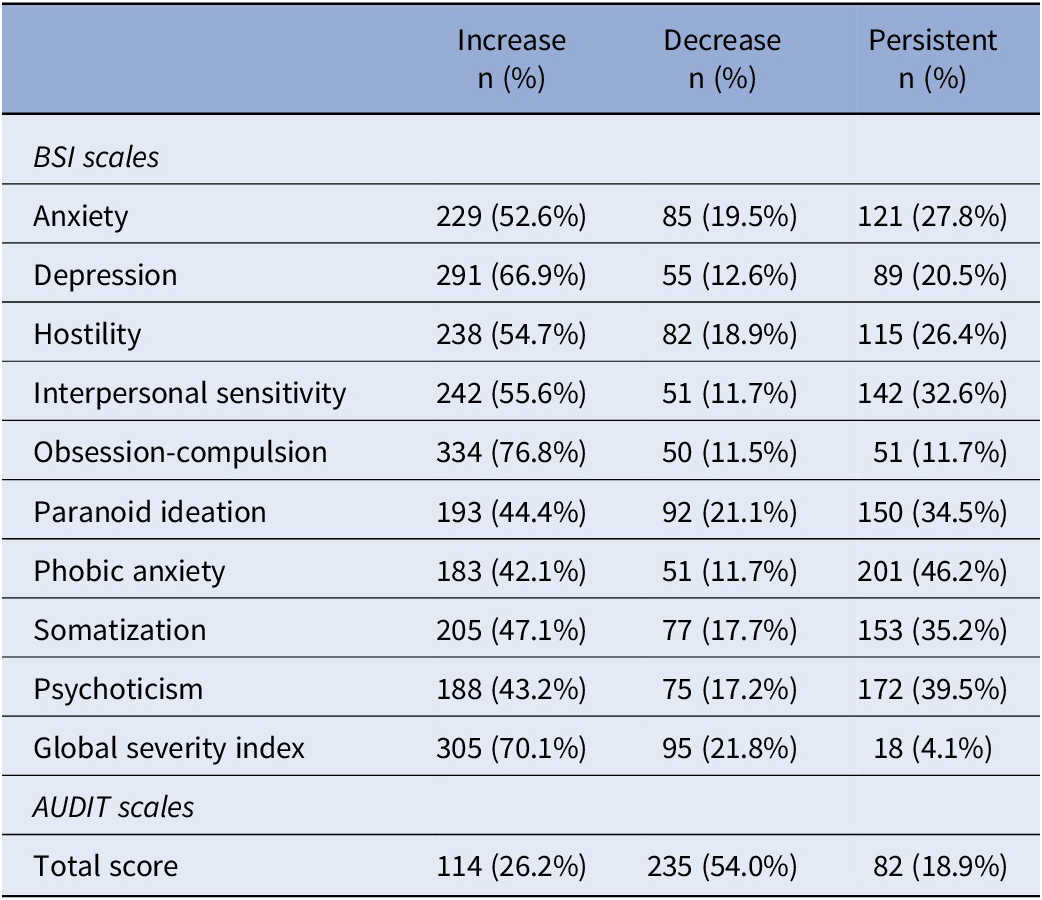

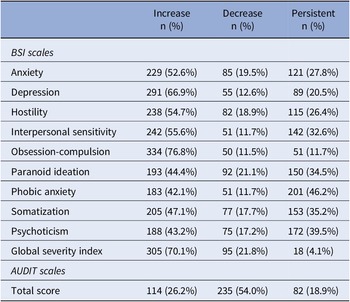

Table 2. Changes from pre-pandemic to during the pandemic grouped in clusters

SHAP models showed that changes in depression and paranoid ideation were the strongest factors for alcohol use during COVID-19, and changes in anxiety, depression, and paranoid ideation were most strongly associated with changes in alcohol use pre- versus during COVID-19 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Left: SHAP models for the relative impact of difference scores of psychological symptoms (BSI scales) pre- versus during COVID-19 for alcohol consumption (AUDIT scores). Right: SHAP models for the relative impact of difference scores of psychological symptoms (BSI scales) pre- versus during COVID-19 for difference scores in alcohol consumption (AUDIT scores).

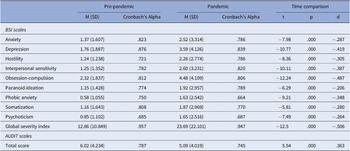

Moreover, while depression was mainly predictive for a decrease in alcohol use, anxiety served as the main factor for an increase in alcohol consumption pre-compared to during COVID-19 (Figure 5). The classification model achieved an overall accuracy of 56.63%, which, while modest, exceeds the chance level of 50% and reflects the complexity of the relationship between psychological symptoms and alcohol use. The detailed classification report showed varying precision, recall, and F1 scores for different groups, highlighting the model’s strengths and weaknesses in predicting categories of alcohol consumption, with the following performance metrics: a precision of 0.25 for class 0 (no change in AUDIT scores), 0.59 for class 1 (decrease in AUDIT scores), and 0.67 for class 2 (increase in AUDIT scores), with corresponding recall values of 0.14, 0.86, and 0.31, respectively (Figure 5). The weighted average F1 score was 0.52, reflecting the model’s overall balanced performance across different classes. Results of cross-validation and interaction plots are presented in Supplementary Material 8–11.

Figure 5. Left: The classification report for the prediction of three alcohol consumption classes pre- versus during COVID-19 by changes in psychological symptoms pre- versus during COVID-19. Middle: The confusion matrix, which illustrates that the model had the highest recall for class 1, suggesting that it was particularly effective in identifying this group. Right: Overview on the number of participants in each of the clustered groups by psychological symptom scales and alcohol use. Note: class 0 = no change in alcohol use pre- versus during COVID-19, class 1 = decrease in alcohol consumption pre- versus during COVID-19, and class 2 = increase in alcohol consumption pre- versus during COVID-19.

Discussion

Studies have demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a significant increase in psychological symptoms and changes in alcohol consumption patterns (e.g., [Reference Avena, Simkus, Lewandowski, Gold and Potenza1–Reference Qi, Zhang, Robinson, Bobou, Gourlan and Winterer3]). However, there remains limited understanding of the interactions between these factors during the pandemic and how they differ from the pre-pandemic period. In this study, we used longitudinal data from a large cohort study and applied group-based analyses, correlation techniques, and machine learning approaches (SHAP and classification models) to investigate the associations between psychological symptoms and alcohol use in individuals during early adulthood, comparing the pre-pandemic to the early phase of COVID-19.

Existing models of alcohol consumption have highlighted factors such as stress, social reinforcement, and psychological symptoms like anxiety and depression as key influences on drinking patterns [Reference Arya and Gupta24, Reference Ornell, Moura, Scherer, Pechansky, Kessler and von Diemen25]). However, global crises like the COVID-19 pandemic may have disrupted these dynamics. The pandemic has been perceived as a stressful and negative life event [Reference Mousavi, Hooshyari and Ahmadi26], altered the social environment and associated factors [Reference Kapecki27], and resulted in an increase in psychological symptoms, including anxiety and depression [Reference Hawes, Szenczy, Klein, Hajcak and Nelson28].

Consistent with previous studies (also, e.g., [Reference Avena, Simkus, Lewandowski, Gold and Potenza1–Reference Qi, Zhang, Robinson, Bobou, Gourlan and Winterer3, Reference Roberts, Rogers, Mason, Siriwardena, Hogue and Whitley9]), we observed significantly higher levels of psychological symptoms and lower levels of alcohol consumption when comparing the pre-pandemic periods to the early phase of COVID-19. The rise in psychological symptoms likely reflects reactions to the numerous challenges brought about by the pandemic. Although some previous studies have reported an increase in alcohol use [Reference Roberts, Rogers, Mason, Siriwardena, Hogue and Whitley9, Reference Roberts, Wong, Jenkins, Neher, Sutton and O’Meara29], the overall decline in alcohol consumption observed in our study aligns with findings from other studies [Reference Qi, Zhang, Robinson, Bobou, Gourlan and Winterer3, Reference Rossow, Bye, Moan, Kilian and Bramness30]. This reduction may be attributed to social contact restrictions and limited access to alcohol during lockdowns in the early period of the pandemic [Reference Davies, Puljevic, Gilchrist, Potts, Zhuparris and Maier31], when our COVID-19 data were collected.

The age range of our sample (young adulthood) is also a relevant factor, given this period’s heightened sensitivity to environmental and health influences and the critical role of social factors and contexts, including those related to alcohol consumption.

Moreover, previous findings reporting increases, decreases, or no changes in alcohol use when comparing pre- and during COVID-19 periods highlight substantial individual variation in alcohol use. This suggests the presence of underlying effects that may not be immediately apparent, warranting further investigation to better understand alcohol use behaviors during the pandemic.

When classifying individuals into groups based on increased, decreased, or stable alcohol consumption from pre- to during COVID-19, distinct psychological symptoms emerged as predictors of these changes. Anxiety was the primary factor associated with increases in alcohol use, while depression was more strongly linked to decreases or stable patterns of alcohol consumption.

A recent study using data from the same sample, along with data from clinically depressed individuals, identified varying trajectories of depression during the pandemic [Reference Qi, Zhang, Robinson, Bobou, Gourlan and Winterer3]. These findings underscore the importance of considering potentially distinct associations when examining risk and resilience factors during, and now also following, the pandemic.

Such distinct associations were also observed in our study. Coping behaviors may have intensified during the pandemic, potentially shifting the motives for alcohol use – for example, from social motives driven by peer relationships to internal reinforces such as feelings and thoughts [Reference Conrod, Pihl and Vassileva13, Reference Cooper14].

Prior to the pandemic, we observed significant positive correlations between alcohol consumption and psychological symptoms of anxiety and psychoticism. During the pandemic, additional significant correlations emerged, including those with depression, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and interpersonal sensitivity. While depression had a minimal influence on alcohol consumption before COVID-19, it became the most influential factor during the pandemic.

In our analyses, we utilized the total score of the AUDIT questionnaire as a measure of alcohol-related behaviors (according to [Reference Reinert and Allen32]). While the global AUDIT score is primarily a tool for assessing the risk of alcohol use disorder, it also reflects a comprehensive information that integrates both consumption patterns and alcohol-related consequences. This approach aligns with our study’s objectives, as it allows for a holistic understanding of changes in alcohol use behaviors (see also [Reference Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders and Monteiro22]) and their associations with psychological symptoms. In the manuscript, we therefore speak about alcohol use behaviors when referring to the score.

While these findings underscore the critical role of psychological symptoms in influencing alcohol use behaviors during crises [Reference Clay and Parker33] and suggest that the specific symptoms influencing alcohol use may shift during challenging periods, one could also argue that these differences might be related to changes in the variance of each variable pre- compared to during COVID-19. However, these differences were not statistically significant (see Supplementary Information). Additionally, the pre-COVID-19 levels could have affected the change-related associations [Reference Qi, Zhang, Robinson, Bobou, Gourlan and Winterer3], which is why we included them as covariates in our analyses. Therefore, the observed effects should primarily be attributed to the pandemic itself, along with its numerous disruptions and consequences. To further investigate the relationship between psychological symptoms and alcohol use, we examined whether baseline anxiety predicted later alcohol use while controlling for baseline AUDIT scores. The results did not indicate a significant longitudinal association, suggesting that baseline anxiety alone does not drive changes in alcohol-related behaviors beyond the initial alcohol use level (see Supplementary Information). This finding underscores the complex interplay between psychological distress and drinking behaviors, indicating that additional factors, such as coping mechanisms, social influences, or personality traits, may contribute more prominently to changes in alcohol use over time.

Addictive behaviors have long been understood through multifaceted models that encompass genetic, environmental, and psychological factors [Reference Conrod and Nikolaou34]. This approach is crucial for understanding the changes and patterns we observed in the associations between psychological symptoms and alcohol consumption before and during COVID-19, as other factors may have influenced these dynamics. Future research should therefore incorporate more psychosocial and environmental data, when available, to further explore these interactions during such critical periods in a medical crisis, helping to inform strategies for potential future scenarios. Moreover, future studies should continue to investigate these interactions during later stages of the pandemic and in the post-pandemic period.

Our study has several limitations. The reliance on self-reported data, while common in epidemiological research, may introduce biases such as recall or social desirability bias. Future research could incorporate physiological markers to complement self-reported behaviors. Additionally, the generalizability of our findings may be limited to specific demographic or cultural contexts, underscoring the need for cross-cultural studies to better understand global patterns of substance use during crises. Another limitation pertains to participant retention and representativeness. The COVID assessments were an additional voluntary measure within the longitudinal IMAGEN framework, leading to a reduced sample size compared to the original cohort. While we included only participants with complete data at both COVID timepoints, this selection process may have introduced biases, which should be kept in mind regarding the generalizability of our findings. Finally, one limitation pertains to the use of the AUDIT score. The AUDIT is widely used to assess alcohol-related behaviors [Reference Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders and Monteiro22, Reference Karyadi and Cyders35]; however, we also want to note that it is primarily designed to identify individuals at risk for alcohol use disorder rather than to directly measure alcohol consumption levels. Given that the total AUDIT score integrates both consumption-related and consequence-related factors, we decided to use this score as our indicator, as it fits with our hypotheses and with previous studies as an important aspect for comparisons, but we also want to specify that the categorization of alcohol use changes (increased, decreased, and persistent use) done in the present study is based on a broader risk framework rather than solely on consumption frequency. For future studies, it could be interesting to consider also alternative measures that more precisely capture consumption behaviors to reflect other issues of alcohol use.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study explored the multiple associations between psychological symptoms and alcohol use both a few years before and very early during the COVID-19 pandemic in an age-homogeneous sample of young adults. Our findings suggest a change in these associations, with depression appearing as the main factor linked to a decrease in alcohol use during the pandemic, but not before, and anxiety being the primary factor associated with an increase in alcohol use before versus during COVID-19. These results offer valuable insights for prevention and intervention strategies. Future studies should further refine and complement existing interaction models to understand how extreme environmental stressors interact with pre-existing vulnerabilities to influence alcohol use behaviors [Reference Arya and Gupta24, Reference Ornell, Moura, Scherer, Pechansky, Kessler and von Diemen25]. Moreover, future research could examine the impact of environmental changes and challenges during later periods of the pandemic and in the post-pandemic. Here, one study on adult twin pairs provided some first information by controlling for genetic and shared environmental factors [Reference Avery, Tsang, Seto and Duncan18]. Still, integrating additional contextual factors, when available, could help enrich strategies for effective public health responses.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2025.2450.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

Members of the IMAGEN Consortium are: Tianye Jia, Tobias Banaschewski, Gareth J. Barker, Arun L. W. Bokde, Sylvane Desrivières, Herta Flor, Antoine Grigis, Hugh Garavan, Penny Gowland, Andreas Heinz, Rüdiger Brühl, Jean-Luc Martinot, Marie-Laure Paillère Martinot, Eric Artiges, Frauke Nees, Dimitri Papadopoulos Orfanos, Tomáš Paus, Luise Poustka, Sarah Hohmann, Sabina Millenet, Juliane H. Fröhner, Michael N. Smolka, Nilakshi Vaidya, Henrik Walter, Robert Whelan, and Gunter Schumann.

Members of the CoviDrug consortium are: Frauke Nees, Rabia Zohair, Karina Janson (Institute of Medical Psychology and Medical Sociology, University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, Kiel University, Kiel, Germany), Tobias Banaschewski, Nathalie Holz, Stella Guldner (Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Central Institute of Mental Health, Medical Faculty Mannheim, Heidelberg University, Mannheim, Germany), Herta Flor, Maren Prignitz (Institute of Cognitive and Clinical Neuroscience, Central Institute of Mental Health, Medical Faculty Mannheim, Heidelberg University, Mannheim, Germany), Olaf Reis, Elisa Wandinger, Antonia Fröhlich (Department of Psychiatry, Neurology & Psychosomatics in Childhood and Adolescence, University Medicine Rostock, Rostock, Germany), Emanuel Schwarz and Ersoy Kocak (Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Central Institute of Mental Health, Medical Faculty Mannheim, University of Heidelberg, Mannheim, Germany; Hector Institute for Artificial Intelligence in Psychiatry, Central Institute of Mental Health, Medical Faculty Mannheim, Heidelberg University, Mannheim, Germany).

Author contribution

The research was conceptualized and designed by F.N., T.B., and H.F. The data were obtained and compiled by D.P.O. and analyzed by K.J. The manuscript was drafted by F.N. and K.J., and critically reviewed for significant intellectual content by T.B., H.F., O.R., E.S., A.L.W.B., S.D., H.G., P.G., A.G., A.H., J.L.M., M.L.P.M., E.A., D.P.O., T.P., L.P., M.S., N.E.H., N.V., H.W., R.W., G.S., and F.N. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the research project “CoviDrug:” The role of pandemic and individual vulnerability in longitudinal cohorts across the life span: refined models of neurosociobehavioral pathways into substance (ab)use? “which has been funded within the Call for proposals for interdisciplinary research on epidemics and pandemics in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak by the German Research Foundation (NE 1383/15–1, BA 2088/7–1, FL 156/44–1, RE 1732/3–1, SCHW 1768/4–1;coordinated by the Institute of Medical Psychology and Medical Sociology, University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel).

In addition, this work received support from the following sources: the European Union-funded FP6 Integrated Project IMAGEN (Reinforcement-related behavior in normal brain function and psychopathology) (LSHM-CT- 2007-037286), the Horizon 2020 funded ERC Advanced Grant ‘STRATIFY’ (Brain network-based stratification of reinforcement-related disorders) (695313), Horizon Europe ‘environMENTAL,’ grant no: 101057429, UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Horizon Europe funding guarantee (10041392 and 10038599), Human Brain Project (HBP SGA 2, 785907, and HBP SGA 3, 945539), and the Chinese government via the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST). The German Center for Mental Health (DZPG), the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF grants 01GS08152; 01EV0711; Forschungsnetz AERIAL 01EE1406A, 01EE1406B; Forschungsnetz IMAC-Mind 01GL1745B), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG project numbers 186318919 [FOR 1617], 178833530 [SFB 940], 386691645 [NE 1383/14–1], 402170461 [TRR 265], and 454245598 [IRTG 2773]), the Medical Research Foundation and Medical Research Council (grants MR/R00465X/1 and MR/S020306/1), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded ENIGMA-grants 5U54EB020403–05, 1R56AG058854–01, and U54 EB020403, as well as NIH R01DA049238, and the National Institutes of Health, Science Foundation Ireland (16/ERCD/3797). NSFC grant 82150710554. Further support was provided by grants from: – the ANR (ANR-12-SAMA-0004, AAPG2019 – GeBra), the Eranet Neuron (AF12-NEUR0008–01 – WM2NA; and ANR-18-NEUR00002–01 – ADORe), the Fondation de France (00081242), the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (DPA20140629802), the Mission Interministérielle de Lutte-contre-les-Drogues-et-les-Conduites-Addictives (MILDECA), the Assistance-Publique-Hôpitaux-de-Paris and INSERM (interface grant), Paris Sud University IDEX 2012, the Fondation de l’Avenir (grant AP-RM-17-013), and the Fédération pour la Recherche sur le Cerveau.

Funded by the European Union. Complementary funding was received by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) under the UK government’s Horizon Europe funding guarantee (10041392 and 10038599). Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union, the European Health and Digital Executive Agency (HADEA), or UKRI. Neither the European Union nor HADEA nor UKRI can be held responsible for them.

Competing interests

Dr. Banaschewski served in an advisory or consultancy role for Lundbeck, Medice, Neurim Pharmaceuticals, Oberberg GmbH, and Shire. He received conference support or speaker’s fee by Lilly, Medice, Novartis, and Shire. He has been involved in clinical trials conducted by Shire and Viforpharma. He received royalties from Hogrefe, Kohlhammer, CIP Medien, and Oxford University Press. The present work is unrelated to the above grants and relationships. Dr. Poustka served in an advisory or consultancy role for Roche and Viforpharm and received speaker’s fee by Shire. She received royalties from Hogrefe, Kohlhammer, and Schattauer. The present work is unrelated to the above grants and relationships. The other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.