INTRODUCTION

Anti‐pluralist politicians and parties that question the legitimacy of political opponents and reject adherence to democratic norms in their speeches (Linz, Reference Linz1978; Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018) have been elected into government in various democracies worldwide. To name just a few examples, President Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil and Prime Ministers Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel and Narendra Modi of India have all consistently shown disdain for political competitors and disapproval of institutions that limit their power, such as judicial bodies and independent media (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016; Haggard & Kaufman, Reference Haggard and Kaufman2021; Waldner & Lust, Reference Waldner and Lust2018).

While the anti‐pluralist rhetoric from such democratically elected leaders poses a threat to democratic stability in itself, such as nurturing public disregard for democratic institutions, evidence indicates that many, but not all, incumbents translate their anti‐pluralist rhetoric into practice during their tenure. Just under a third of democracies with a newly elected or re‐elected anti‐pluralist government experienced democratic backsliding in the following year, while two‐thirds did not (Medzihorsky & Lindberg, Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024, p. 8). Although this evidence indeed suggests that anti‐pluralist parties in government can severely harm democracy, the question arises as to why and when some anti‐pluralist incumbents pursue undemocratic reforms while others are more reluctant to do so.

I argue that anti‐pluralist parties are more likely to undermine democracy while in office when citizen support for democratic governance is weak. Conversely, when citizens strongly embrace democracy as a preferred form of government, anti‐pluralist governments are less likely to drive democratic backsliding due to two primary mechanisms. Firstly, assuming incumbents' primary concern is re‐election, anti‐pluralist governments might fear electoral consequences in the subsequent election when citizens are firmly committed to upholding democracy and resisting the subversion of democratic institutions. Secondly, in societies where strong support for democratic governance prevails, attempts to implement undemocratic reforms are more likely to trigger public backlash, such as protests or general strikes. This backlash, in turn, can erode an incumbent's public support and offer the opposition an opportunity to rally against the anti‐pluralist incumbent. Together, these mechanisms help explain the varying degrees to which anti‐pluralist governments induce democratic backsliding.

I test this theory using longitudinal data on public opinion, government party composition and the democratic trajectories of democracies worldwide spanning from 1990 to 2019. Utilizing cross‐country survey data containing items on attitudes towards democratic governance, I employ Bayesian dynamic latent trait models (Claassen, Reference Claassen2019) to estimate evolving citizen support across the globe. I integrate the citizen‐level data with party system indicators from the V‐Party dataset (Lindberg et al., Reference Lindberg, Düpont, Higashijima, Kavasoglu, Marquardt, Bernhard, Döring, Hicken, Laebens, Medzihorsky, Neundorf, Reuter, Ruth‐Lovell, Weghorst, Wiesehomeier, Wright, Alizada, Bederke, Gastaldi, Grahn, Hindle, Ilchenko, Römer, Wilson, Pemstein and Seim2022), including a measure of the extent to which governing parties exhibit an anti‐pluralist rhetoric. This data source provides a unique opportunity to track the global development of party systems concerning their anti‐pluralist rhetoric. Employing dynamic time‐series cross‐section (TSCS) models predicting democratic backsliding, I demonstrate that anti‐pluralist parties in power during periods of low citizen endorsement for democratic governance are linked to episodes of democratic decay. In contrast, citizen support for democracy is unrelated to governments' subsequent anti‐pluralist rhetoric and vice versa.

This article contributes in two main ways to the literature on the dynamics and origins of democratic backsliding. Firstly, while recent research has explored when and why citizens might withdraw support from undemocratic elites during elections (Carey et al., Reference Carey, Clayton, Helmke, Nyhan, Sanders and Stokes2022; Frederiksen, Reference Frederiksen2022; Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Stolle and Bergeron‐Boutin2022), this article investigates whether public opinion regarding democracy affects incumbents' behaviour towards democratic institutions beyond the act of voting. Secondly, whereas earlier studies have often concentrated on either elites or citizens when explaining democratic decline (but see Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2003), this article proposes a theoretical framework that encompasses government composition and citizen attitudes, thereby advancing the integration of agency‐ and mass‐based perspectives on democratic backsliding.Footnote 1

Constraining anti‐pluralist governments: A theoretical framework

Executive constraints and democratic backsliding

Democratic backsliding refers to the ‘state‐led debilitation or elimination of any of the political institutions that sustain an existing democracy’ (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016, p. 5), typically driven by autocratic leaders (Haggard & Kaufman, Reference Haggard and Kaufman2021, p. 1). This form of system change distinguishes more recent forms of regime transformation from previous ones marked by military coups and self‐coups; today, democratically elected political actors usually induce backsliding by progressively undermining liberal democratic institutions and norms (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016, p. 14), while often exploiting the weaknesses of existing democratic institutions (Svolik, Reference Svolik2020, p. 5).

Given the subtler nature of recent autocratization in several democratic systems, scholars have begun to examine the origins of democratic backsliding (Coppedge, Reference Coppedge2017; Diamond, Reference Diamond2021; Gamboa, Reference Gamboa2022; Haggard & Kaufman, Reference Haggard and Kaufman2021; Miller, Reference Miller2021; Waldner and Lust, Reference Waldner and Lust2018). Some studies focus on how citizen preferences and behaviour contribute to system change at the country level (Claassen, Reference Claassen2020; Dalton & Welzel, Reference Dalton and Welzel2014; Welzel & Inglehart, Reference Welzel and Inglehart2008), while others predominantly analyse political elites' behaviour towards democratic institutions (Albertus & Menaldo, Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018; Bartels, Reference Bartels2023; Cleary & Öztürk, Reference Cleary and Öztürk2022; Capoccia, Reference Capoccia2005; Kneuer, Reference Kneuer2021; Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Mainwaring & Pérez Liñan, Reference Mainwaring and Pérez Liñan2013; Ziblatt, Reference Ziblatt2017), leaving citizens' potential to constrain political elites in their decision to undermine democracy less explored.

At the elite level, many democracies have witnessed the emergence of anti‐pluralist parties that reject the principles of forbearance and mutual toleration (Linz, Reference Linz1978; Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Medzihorsky and Lindberg, Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024). Forbearance entails not only respect for the institutions that limit politicians' and parties' power but also an adherence to the spirit that guided the establishment of these institutions. Mutual toleration involves recognizing the legitimacy of political opponents and treating them as equally valid participants in the political competition despite ideological differences (Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018).

An alternative perspective on political actors rejecting these principles involves studying them through the lens of populism (Grzymala‐Busse, Reference Grzymala‐Busse2019). In the context of democratic backsliding in Central Europe, Vachudova (Reference Vachudova2020) suggests that certain parties, including those in power, as in Hungary and Poland, employ a strategy of gaining support and power by explicitly emphasizing ethnic differences. While these ethnopopulist actors also challenge key democratic principles, they construct a narrative centered around national and ethnic identities to justify these transgressions (Vachudova, Reference Vachudova2020, Reference Vachudova2021). To precisely capture the rhetoric used by elites that target crucial components of democratic governance, such as forbearance and mutual toleration, I here employ the term ‘anti‐pluralism’ as one characteristic among several in this stream of scholarship.

Although anti‐pluralist politicians and parties reject liberal democratic principles, the presence of such actors in a democracy does not have to lead to the dismantling of democratic institutions per se. For one, even when anti‐pluralist actors receive a high number of votes in elections, whether they assume executive power hinges largely on the behaviour of other elites. In systems where government coalitions are the norm, such as Poland, Israel and Germany, pluralist parties can refuse to form a coalition with anti‐pluralist parties, thereby preventing them from ascending to power. In systems with mainly two competing parties, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, party elites can refuse to support anti‐pluralist elites and thereby harm their prospects of being selected as candidates for public office (Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018).

For another, even when anti‐pluralists assume power, democracy may still remain intact. According to Medzihorsky and Lindberg (Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024, p. 8), in instances where anti‐pluralist parties take over or are confirmed in government, 29 per cent of democracies experience democratic decline in the subsequent year. While this share is dramatically larger when anti‐pluralists and not pluralists are in government (only 4 per cent of democracies decline in the subsequent years if pluralist parties are in government), 71 per cent of democracies remain intact in the post‐election year, despite being governed by anti‐pluralist parties. This raises the question: Why do anti‐pluralist parties subvert democracy when elected into government while others do not?

Various factors may constrain anti‐pluralist governments in their pursuit of dismantling democratic institutions. To name only the most significant ones, the judiciary or other horizontal veto players such as a president in parliamentary systems or the lack of (super‐)majorities in parliament can hinder the executive from inducing backsliding. Moreover, international influences, such as the focus of democracy promotion schemes on the executive and elections, can lead to a strengthening of the executive branch vis‐à‐vis other democratic institutions (Meyerrose, Reference Meyerrose2020). Similarly, citizens may exert influence on how elites behave in public office. Given that democratic backsliding is characterized by the fact that electoral competition remains intact while being tilted in favour of the incumbent, it becomes even more relevant to examine how citizen attitudes and behaviour can affect whether their government undermines democratic institutions. Acknowledging the host of different constraints on government action (cf. Lührmann et al., Reference Lührmann, Marquardt and Mechkova2020), this article thus focuses on the potential impact of citizens on anti‐pluralist governments' conduct towards democratic institutions.

In electoral democracies, citizens can affect their governments in two principal ways: electoral turnover and rational anticipation on the part of elites, leading to policy shifts among already elected politicians (Stimson et al., Reference Stimson, MacKuen and Erikson1995). Firstly, citizens can replace their leaders with ones that align more with their ideological preferences (electoral turnover). In the context of regime change, citizens have the opportunity to support pluralist candidates and parties that embrace liberal democratic norms and, similarly, refuse to vote for politicians who embrace anti‐pluralist principles. However, citizens often support anti‐pluralist politicians, even though they support democratic ideals in principle (Wuttke et al., Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2022). Recent literature has addressed this puzzle, mostly by leveraging survey experimental evidence. This evidence indicates that citizens prioritize selecting co‐partisans over democratic politicians as their leaders (Carey et al., Reference Carey, Clayton, Helmke, Nyhan, Sanders and Stokes2022; Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Stolle and Bergeron‐Boutin2022; Svolik, Reference Svolik2019). Hence, partisan affiliation usually dominates electoral campaigns and voting behaviour, which is why partisan voters often acquiesce to co‐partisans who have previously made undemocratic claims. Moreover, many citizens might not be aware when political candidates have violated democratic principles, making it even less likely that voters would deliberately turn against a co‐partisan candidate who has shown undemocratic tendencies in the past.

While the direct influence of citizens on the democratic trajectory of their country through electoral turnover has been extensively studied in recent work, more indirect forms of citizen attitudes towards democracy and their impact on the government's behaviour towards democratic institutions remain understudied. Elites may take into account public preferences for policies and institutional change when in office, thereby seeking to be confirmed in office at the next election (rational anticipation; see Stimson et al., Reference Stimson, MacKuen and Erikson1995, p. 545). So far, only the direct effects of public opinion on institutional change, but not on the government's conduct towards democratic institutions, have been studied. According to these studies, in the long run, citizen preferences and behaviour can nurture democratic development, depending on the level of public commitment to democracy (Dalton & Welzel, Reference Dalton and Welzel2014; Welzel & Inglehart, Reference Welzel and Inglehart2008). More recently, Claassen (Reference Claassen2020) found that the prevalence of democratic attitudes in society contributes to maintaining democratic systems, suggesting a direct link between citizens' democratic orientation and institutional trajectories, including democratic backsliding.

However, political elites, unlike ordinary citizens, are ultimately responsible for undermining democracy. In other words, as citizens cannot directly induce democratic backsliding, it is critical to understand the pathways through which citizens enable or constrain their government in implementing undemocratic reforms. The question thus remains: Besides voting in elections, how, or whether at all, do citizen attitudes towards democracy influence anti‐pluralist governments' leeway to undermine democratic institutions beyond voting? In the next section, I will argue that citizen preferences for living in a democracy over authoritarian governance constrain even anti‐pluralist governments' decisions regarding undermining democratic institutions.

Citizen support for democracy, rational elite anticipation and democratic backsliding

In contemporary democracies, citizens' policy and institutional preferences have the potential to influence political elites, even without replacing them with ones that align more with their preferences (Burstein, Reference Burstein2003; Kingdon, Reference Kingdon2014; Manza & Cook, Reference Manza, Cook, Manza, Cook and Page2002; Stimson et al., Reference Stimson, MacKuen and Erikson1995). While anti‐pluralist parties in government possess the means to induce undemocratic change when holding executive power, I argue that whether or not they take advantage of these means and begin to implement undemocratic change is conditional on citizens' commitment to democratic governance.

A key underlying assumption of this argument, and theories of dynamic representation more generally (Stimson et al., Reference Stimson, MacKuen and Erikson1995, p. 544), is that elites seek to remain in power to pursue their policy preferences. Anti‐pluralist parties in government, therefore, aim to retain their governmental status while simultaneously seeking to reform democratic institutions to accumulate political power and reduce the chances of electoral turnover in the long run (Vachudova, Reference Vachudova2021, p. 490). Such reforms may concern but are not limited to weakening judicial constraints on the executive, limiting media pluralism and restraining the opposition's political activities (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016, pp. 11–13).

However, under some circumstances, namely strong citizen support for democracy, implementing such undemocratic reforms would incur such great costs for the government that it refrains from pursuing such severe reforms in order to maintain public support and remain in office. Hence, in cases where undermining democratic institutions would seriously risk its public support, anti‐pluralist incumbents will tend to restrain their undemocratic institutional preference. That anti‐pluralist governments prioritize enjoying public support and thereby increasing their chances of re‐election resonates with recent work on democratic backsliding. Game theoretic approaches presume that incumbents' key aim is to secure another tenure at the next election (Chiopris et al., Reference Chiopris, Nalepa and Vanberg2021; Luo & Przeworski, Reference Luo and Przeworski2023), which also allows for implementing policy platforms. Studying opposition behaviour in Latin American democracies that experienced backsliding, Gamboa (Reference Gamboa2022, p. 31) argues that political actors seek office to implement their policy preferences, but since reforms can only be achieved in public office, autocratic incumbents and opposition forces' main priority is to succeed in electoral contests.

Drawing on the assumption that anti‐pluralist incumbents' priority is to retain public support and thereby secure re‐election, I argue that if anti‐pluralist governments are confronted with a public that opposes undemocratic reforms, they will reduce the intensity of attacks on democratic institutions for the sake of retaining electoral support. More specifically, there are two main mechanisms by which citizens can restrain governments from undermining democracy beyond elections. Firstly, in contexts where citizen support for democracy is strong, anti‐pluralist governments may risk being punished for their undemocratic behaviour by losing the public's approval and votes in future elections (anticipated electoral punishment). Given the incremental character of democratic backsliding (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016, p. 14), anti‐pluralist governments usually do not dismantle democratic institutions at once but undermine certain norms and rules piecemeal. Consequently, backsliding is a dynamic process: the incumbent attacks or disregards a particular democratic institution (e.g., judicial independence) and then observes how other branches of government, the public and other constraining actors such as international organizations react to her actions.

In the short term, the more strongly citizens endorse democratic ideals, the more the anti‐pluralist government risks losing citizens' approval. This may have immediate repercussions on the government's ability to govern the country efficiently. In the longer term, an electorate that widely subscribes to democratic norms will be more likely to withdraw support from elites who have induced democratic backsliding than societies with less support for democracy as a form of government. As a result, the fewer citizens value living in a democracy, the less the anti‐pluralist government risks losing the public's approval, and the more likely it will be to attack democratic institutions. In other words, anti‐pluralist parties in power need to weigh the risk of losing political support from the public when weakening checks and balances against the potential advantages of such reforms.

The second mechanism pertains to immediate public backlash, such as protests or large‐scale strike action, to undemocratic reforms. Closely related to the punishment mechanism, anti‐pluralist governments operating in a societal environment that is nevertheless supportive of democratic governance may experience not only declining support but also active public mobilization. In societies where citizens are highly supportive of democratic rule, anti‐pluralist governments can expect to face more vigorous opposition when seeking to induce undemocratic institutional change, most notably by oppositional parties (Cleary & Öztürk, Reference Cleary and Öztürk2022), protest movements (Dimitrova, Reference Dimitrova2018; Laebens & Lührmann, Reference Laebens and Lührmann2021; McCarthy, Reference McCarthy2023) and civil society organizations more generally (Bernhard et al., Reference Bernhard, Hicken, Reenock and Lindberg2020; Greskovits, Reference Greskovits2015). The realistic scenario of sparking protest against undemocratic reforms may furthermore increase the cost of attacking democratic institutions and deter anti‐pluralist parties in power from undermining democracy in the first place.

Several instances worldwide illustrate the significance of public opposition in democracies where governments enact changes to institutions or are accused of violating democratic norms. In early 2023, tens of thousands of demonstrators flooded the streets in protest of Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador's proposal to revamp the nation's electoral commission, which included substantial reductions in funding (Reuters, 2023). Concurrently, sizable demonstrations erupted in Poland, denouncing the government's actions in undermining checks and balances, including the judiciary and media pluralism (AP News, 2023). France experienced protests as well, triggered by President Emmanuel Macron's implementation of a pension reform despite lacking a legislative majority for the proposal (France 24, 2023). In Israel, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's announcement of a plan to overhaul the judicial system sparked unprecedented protests, prompting trade unions to call for general strikes (Gidron, Reference Gidron2023). These events can all be considered robust public responses to governmental attempts to stretch power.

Clearly, often enough, this public backlash does not prevent governments from proceeding with the specific reform plan based on which protests emerged. Indeed, in many of the cases described above, the governments eventually implemented their plans despite forceful public backlash. Nonetheless, according to my argument, these public reactions send a strong signal to the government that inducing undemocratic change can be costly: resistance and opposition to the government's actions receive much public attention and demonstrate that the planned reforms to democratic institutions or violations of democratic principles are not based on a national consensus and may come with considerable audience costs. In its most extreme form, severe attacks on democracy, such as large‐scale electoral fraud, can lead to revolutionary episodes, as in several post‐communist countries (Kuntz & Thompson, Reference Kuntz and Thompson2009), whereby authoritarian‐leaning governments radically lost their grip on power as they underestimated the pressure of public backlash against their undemocratic actions. Public protests, for instance, signal to the government that undemocratic change does not go unnoticed and may thus reduce its willingness to subvert democracy in the future. Hence, to remain in power, anti‐pluralist parties need to take into account the potential of public backlash in their decision to undermine democratic institutions.

In summary, anti‐pluralist parties in power are confronted with a trade‐off that, in part, hinges on citizens' support for democratic governance. If citizens' commitment to selecting political leaders by democratic means is weak, anti‐pluralist incumbents can proceed with undermining checks and balances because the possibility of citizen punishment and backlash is low. By contrast, if citizens are firmly committed to democratic governance, implementing undemocratic reforms comes at a much higher cost, risking losing citizen support and provoking a backlash from opposition parties and protest movements. This argument translates into the following hypothesis:

Elite‐citizen interaction hypothesis: As anti‐pluralist rhetoric within a government rises and citizen support for democracy declines, more democratic backsliding occurs.

It is important to note that once severe democratic backsliding unfolds, governments acquire a broader array of tools to shape public opinion and perceptions of their governance (Vachudova, Reference Vachudova2021, p. 490). Governments that initiate backsliding frequently seize control of media outlets (Kwode et al., Reference Kwode, Asekere and Ayelazuno2024; Metin & Ramaciotti Morales, Reference Metin and Ramaciotti Morales2024), which can exert considerable influence in reporting violations of democratic institutions and framing them as undemocratic. If such reporting becomes restricted, citizens may become less informed about incumbent assaults on democratic institutions, reducing the likelihood of holding undemocratic governments accountable through elections or protests. Government‐aligned media may assert that such reforms would enhance democracy, a narrative that could gain even more traction among citizens if alternative media perspectives are unavailable. Furthermore, following instances of elite transgressions, citizens might experience a sense of relief that these transgressions did not escalate further. As a consequence, citizens who value democracy in principle may thus continue to support incumbents who undermine democratic institutions (Grillo & Prato, Reference Grillo and Prato2023).

Consequently, the impact of citizen support for democracy will be most pronounced in democracies where a diverse range of media sources is accessible, and opposition activities remain largely unconstrained. Conversely, in contexts where these freedoms are significantly curtailed, citizens' commitment to democracy is less likely to constrain the undemocratic actions of anti‐pluralist governments.

Analysing democratic decline from 1990 to 2019

According to my theory, anti‐pluralist parties in power are more likely to induce democratic backsliding when citizen support for democracy is low. By contrast, when citizens are strongly committed to democracy, anti‐pluralist governments are less likely to undermine democratic institutions. In the remainder of this article, I test the hypothesis using longitudinal data for democracies' institutional development, government composition, citizen support for democracy and a host of control variables.

Dependent variable: Downturn in liberal democracy

The primary outcome variable of this study is the degree of democratic backsliding experienced by a country each year. A common approach to measuring democratic change is to rely on the Varieties of Democracy (V‐Dem) project (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Luhrmann, Marquardt, McMann, Paxton, Pemstein, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Wilson, Cornell, Alizada, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Hindle, Ilchenko, Maxwell, Mechkova, Medzihorsky, von Römer, Sundström, Tzelgov, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2023), which is widely regarded as the most comprehensive data project on democratic development to date (Claassen, Reference Claassen2020, pp. 4–5). The V‐Dem dataset contains various measures of the democratic quality of most countries worldwide, enabling extensive large‐

![]() $N$ cross‐country analyses. V‐Dem's liberal democracy index is the most encompassing measure in this context, as it includes indicators based on Dahl's polyarchy concept (Dahl, Reference Dahl1971), checks and balances and the protection of minority rights. I opt for this broader democracy concept to account for the diverse ways in which democratic backsliding can manifest (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016). I rescale the liberal democracy index from 0 to 100.Footnote 2 In Online Appendix D, I investigate whether the findings also apply to predicting the decline of electoral democracy and find similar patterns.

$N$ cross‐country analyses. V‐Dem's liberal democracy index is the most encompassing measure in this context, as it includes indicators based on Dahl's polyarchy concept (Dahl, Reference Dahl1971), checks and balances and the protection of minority rights. I opt for this broader democracy concept to account for the diverse ways in which democratic backsliding can manifest (Bermeo, Reference Bermeo2016). I rescale the liberal democracy index from 0 to 100.Footnote 2 In Online Appendix D, I investigate whether the findings also apply to predicting the decline of electoral democracy and find similar patterns.

As I aim to predict democratic backsliding and my theoretical framework refers to anti‐pluralist governments' decisions to induce democratic backsliding, I focus exclusively on negative changes in a country's democracy score.Footnote 3 More precisely, I adopt the measure used by Teorell (Reference Teorell2010) for my outcome variable:

where

![]() $D_{it}^{-}=\text{min}\lbrace D_{it},D_{it-1}\rbrace$ (Teorell, Reference Teorell2010, p. 177). I use absolute values so that higher scores indicate more backsliding, and all upturn observations are assigned a value of zero. While this analysis focuses on democratic downturns, future work may investigate the determinants of democratization or democratic deepening using a similar statistical framework.

$D_{it}^{-}=\text{min}\lbrace D_{it},D_{it-1}\rbrace$ (Teorell, Reference Teorell2010, p. 177). I use absolute values so that higher scores indicate more backsliding, and all upturn observations are assigned a value of zero. While this analysis focuses on democratic downturns, future work may investigate the determinants of democratization or democratic deepening using a similar statistical framework.

Independent variables

Anti‐pluralist parties in government

A key independent variable of interest pertains to the extent of anti‐pluralist rhetoric among parties in government. I build on the anti‐pluralism index from the V‐Party dataset (Lindberg et al., Reference Lindberg, Düpont, Higashijima, Kavasoglu, Marquardt, Bernhard, Döring, Hicken, Laebens, Medzihorsky, Neundorf, Reuter, Ruth‐Lovell, Weghorst, Wiesehomeier, Wright, Alizada, Bederke, Gastaldi, Grahn, Hindle, Ilchenko, Römer, Wilson, Pemstein and Seim2022), which comprises a weighted average of the following four components: demonization of opponents, rejection of democratic pluralism, disregard for the rights of political minorities and tolerance of political violence. These four indicators reflect political parties' discourse towards the democratic process and provide a comprehensive measure of a political party's alignment with liberal democratic values.Footnote 4

I develop a weighted measure of anti‐pluralist parties in government, drawing on V‐Party anti‐pluralism scores and seat share of parties in parliament participating in government. Specifically,

where

![]() $p_{ijt}$ denotes the anti‐pluralistism scores of parties that either participated in government as a senior (head of government belongs to this party) or junior (ministers belong to this party but not the head of government) partner in country

$p_{ijt}$ denotes the anti‐pluralistism scores of parties that either participated in government as a senior (head of government belongs to this party) or junior (ministers belong to this party but not the head of government) partner in country

![]() $j$ and year

$j$ and year

![]() $t$. To account for varying party dominance in coalition governments, this score is multiplied by the seat share gained at the previous election,

$t$. To account for varying party dominance in coalition governments, this score is multiplied by the seat share gained at the previous election,

![]() $s_{ijt}$. Finally,

$s_{ijt}$. Finally,

![]() $n_{jt}$ is the number of government parties in a country

$n_{jt}$ is the number of government parties in a country

![]() $j$ in year

$j$ in year

![]() $t$. This measure is assigned to each annual observation during a legislative period, where the score is (re‐)calculated for each party system in election years. In a few cases, data on parties' anti‐pluralist orientation are unavailable from 1990 onward. In such cases, I assign anti‐pluralist government scores from the first expert coding recorded onward.Footnote 5 Substantially, higher anti‐pluralist government scores indicate more prevalence of anti‐pluralist rhetoric in governmental parties.

$t$. This measure is assigned to each annual observation during a legislative period, where the score is (re‐)calculated for each party system in election years. In a few cases, data on parties' anti‐pluralist orientation are unavailable from 1990 onward. In such cases, I assign anti‐pluralist government scores from the first expert coding recorded onward.Footnote 5 Substantially, higher anti‐pluralist government scores indicate more prevalence of anti‐pluralist rhetoric in governmental parties.

Citizen support for democracy

To assess global citizen support for democracy over time, I use Bayesian dynamic latent trait modelling (Claassen, Reference Claassen2019). This method leverages the abundance of survey studies that enquire about respondents' views on democracy. Despite the numerous cross‐sectional surveys conducted in recent decades, the phrasing of survey items on democracy varies, which hampers direct comparisons of citizen support for democracy. Similarly, survey data for most countries are sporadic over time, complicating the study of the influence of public opinion on variables of interest such as citizen support for democracy.

Claassen's Bayesian dynamic latent trait model addresses these challenges by estimating smooth country‐year panels based on multiple survey projects and diverse items. Accordingly, I adopt this approach by applying latent trait models to survey items related to democracy and rejecting autocratic forms of governance from 1990 to 2019. The data up to 2015 come from Claassen (Reference Claassen2020) and were extended with more recent survey projects by Tai et al. (Reference Tai, Hu and Solt2024).Footnote 6 These survey items capture respondents' self‐reported support for democracy or opposition to non‐democratic alternatives, such as military rule or unconstrained leadership. The data consist of 4,710,679 individual responsesFootnote 7 across 145 countries, with a total of 61 different items measuring citizens' attitudes towards democracy. The model diagnostics confirm that the parameters have appropriately converged across all four chains (see Online Appendix A.2.1).Footnote 8

Importantly, consistent with Claassen (Reference Claassen2019), Online Appendix A.2.2 demonstrates that all survey items load onto the country's citizen support estimates in the expected direction: the more survey respondents in a given country support a given item about democracy, the higher the country's citizen support estimate obtained from the latent trait analysis. Furthermore, consistent with the literature (Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Ajzenman, Aksoy, Fiszbein and Molina2022; Edgell et al., Reference Edgell, Wilson, Boese and Grahn2020), Online Appendix A.2.3 reports that countries with a higher democratic stock tend to exhibit more robust citizen support for democracy. However, there are a few notable outliers, such as the United States as of 2019, which had lower support than Venezuela, a country that experienced substantive democratic decline over the last decades.

To examine whether the hypothesis guiding this article (that more anti‐pluralist rhetoric of governments combined with weaker citizen support for democracy increases the severity of democratic backsliding) holds empirically, I introduce an interaction between year‐country scores for public opinion on democracy and the anti‐pluralist government indicator. I follow Hainmueller et al. (Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2019) in assessing whether the estimate satisfies additional assumptions (i.e., linearity and common support) necessary to draw reliable conclusions from interaction estimates.

Control variables

Scholarship on democratic backsliding has proposed a few other potential causes of decaying democratic structures, most notably growing polarization of society, clientelistic party behaviour, the diffusion of regime types to neighbouring countries, a country's experience with democracy and economic development.

Polarization

Polarized societies are often considered highly susceptible to backsliding (Arbatli & Rosenberg, Reference Arbatli and Rosenberg2021). McCoy and Somer (Reference McCoy and Somer2019) argue that, within the context of democratic backsliding, political elites seek to divide the electorate into two opposing factions, a phenomenon they refer to as ‘pernicious polarization’. In such environments, both citizens and elites may become less concerned about safeguarding democratic institutions and more focused on their ideological priorities. Polarization can be observed at both the elite and citizen levels (Cinar & Nalepa, Reference Cinar and Nalepa2022), with both groups potentially becoming polarized along various dimensions, such as policy preferences (Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020) or partisan animosities (Bantel, Reference Bantel2023; Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019).

I utilize V‐Dem's polarization measure as an indicator to assess whether a society is divided between antagonistic political factions. In doing so, I follow the approach of Somer et al. (Reference Somer, McCoy and Luke2021), who used this measure to investigate the impact of polarization on democratic decline. They found substantial evidence supporting that a polarized society contributes to backsliding. However, it is important to acknowledge that this measure does not encompass all aspects of elite and mass polarization (see van der Veen, Reference van der Veen2023). In Online Appendix B, I examine the correlation between affective polarization measured in a subset of counties and years and V‐Dem's polarization index, which turns out to be moderately associated.

Clientelism

Another factor potentially leading to a decline in democratic governance is when voting behaviour is mainly driven by party–voter relationships based on the exchange of resources against political support (Mares & Young, Reference Mares and Young2018). Importantly, clientelistic ties can prevent citizens from defecting from political candidates who have shown undemocratic conduct. Citizens relying on financial support from the anti‐pluralist incumbent would risk losing these material benefits under a different government. In other words, such voters fail to serve as a check on the undemocratic behaviour of political actors, widening the anti‐pluralist incumbent's latitude to undermine democracy. By leveraging V‐Party clientelism party scores, I determine to what extent clientelistic parties dominate a national government. Specifically, a party with a high score on this indicator provides targeted goods in exchange for electoral support. The dominance of such parties in parliament is computed as for anti‐pluralist parties in government, where

![]() $p_{ijt}$ denotes each party's clientelism score.Footnote 9

$p_{ijt}$ denotes each party's clientelism score.Footnote 9

Democracy diffusion

A society's geographic environment may similarly influence the domestic sphere and its institutional development. The diffusion argument has been particularly prominent in democratization theory, where it is argued that democratic spells in adjacent states can trigger a transition process in hitherto autocratically governed systems (Wejnert, Reference Wejnert2014). Similarly, party ideologies and policy stances (Böhmelt et al., Reference Böhmelt, Ezrow, Lehrer and Ward2016) or public opinion towards democratic governance can diffuse across regional borders. Diffusion can thus occur at the institutional, elite or citizen level, affecting a country's democratic development. I include the mean values for each geographic region per annum for the liberal democracy index, the anti‐pluralist parties in government indicator and regional citizen support for democracy.Footnote 10

Democratic stock

A country's accumulated experience with democracy may affect its future chances of witnessing democratic backsliding (Edgell et al., Reference Edgell, Wilson, Boese and Grahn2020; Persson & Tabellini, Reference Persson and Tabellini2009). In this line of argument, countries that have been governed democratically in the past should be less likely to backslide than those with a more limited democratic legacy. A somewhat similar mechanism has been proposed with respect to democratic breakdowns in the interwar period, in which countries with a long tradition of democratic rule have been the most resilient against anti‐democratic attacks despite facing economic recession (Cornell et al., Reference Cornell, Møller and Skaaning2020). Using data from Edgell et al. (Reference Edgell, Wilson, Boese and Grahn2020), I add a democratic stock variable as an independent variable, measuring a country's democratic accumulated experience with a 1 per cent annual depreciation rate.

Economic development

Lastly, previous scholarship has pointed to the effects of a country's economic performance on democratic development (Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Johnson, Robinson and Yared2009; Acemoglu & Robinson, Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2006). Research has also found that a high level of socioeconomic development makes new democracies more resilient against backsliding (Alemán & Yang, Reference Alemán and Yang2011). Put differently, democracies experiencing economic recession should be more susceptible to democratic backsliding than others. To account for countries’ economic development and its potential influence on democratic change, I include GDP per capita and the life expectancy of women at birth in a given country.

Empirical strategy

I employ dynamic TSCS models to predict downward changes in a country's level of democracy. In addition to country/year fixed effects, dynamic TSCS models add lagged values of the dependent variable to the right‐hand side of the regression equation (Baltagi, Reference Baltagi2015; Das, Reference Das2019). In considering previous observations of the dependent variable as a predictor, the model takes into account the history of each country's democratic trajectory. This is substantially important as a decline of democracy is – along with other covariates such as anti‐pluralist government – likely affected by preceding shifts in democratic governance or, in other words, a country's recent experience with backsliding may influence subsequent processes of democratic decline.Footnote 11 I thus implement the following model:

$$\begin{equation} \def\eqcellsep{&}\begin{array}{rcl}{\textit{Back}\textit{slid}\textit{in}{g}_{\textit{it}}}& =& {{\alpha}_{1}\textit{Back}\textit{slid}\textit{in}{g}_{\textit{it}-1}+{\alpha}_{2}\textit{Back}\textit{slid}\textit{in}{g}_{\textit{it}-2}}\\ & & {+\hspace*{0.28em}{\beta}_{1}\textit{Gove}\textit{rnmen}{t}_{\textit{it}-1}+{\beta}_{2}\textit{Citi}\textit{zenS}\textit{uppor}{t}_{\textit{it}-1}}\\ & & {+\hspace*{0.28em}{\beta}_{3}\textit{Gove}\textit{rnmen}{t}_{\textit{it}-1}\ensuremath{\times{}}\textit{Citi}\textit{zenS}\textit{uppor}{t}_{\textit{it}-1}}\\ & & {+\hspace*{0.28em}{\chi}_{\textit{it}-1}+{\mu}_{i}+{\gamma}_{t}+{\varepsilon}_{\textit{it}},}\end{array} \end{equation}$$

$$\begin{equation} \def\eqcellsep{&}\begin{array}{rcl}{\textit{Back}\textit{slid}\textit{in}{g}_{\textit{it}}}& =& {{\alpha}_{1}\textit{Back}\textit{slid}\textit{in}{g}_{\textit{it}-1}+{\alpha}_{2}\textit{Back}\textit{slid}\textit{in}{g}_{\textit{it}-2}}\\ & & {+\hspace*{0.28em}{\beta}_{1}\textit{Gove}\textit{rnmen}{t}_{\textit{it}-1}+{\beta}_{2}\textit{Citi}\textit{zenS}\textit{uppor}{t}_{\textit{it}-1}}\\ & & {+\hspace*{0.28em}{\beta}_{3}\textit{Gove}\textit{rnmen}{t}_{\textit{it}-1}\ensuremath{\times{}}\textit{Citi}\textit{zenS}\textit{uppor}{t}_{\textit{it}-1}}\\ & & {+\hspace*{0.28em}{\chi}_{\textit{it}-1}+{\mu}_{i}+{\gamma}_{t}+{\varepsilon}_{\textit{it}},}\end{array} \end{equation}$$where

![]() $\alpha _{1}$ and

$\alpha _{1}$ and

![]() $\alpha _{2}$ denote the dependent variables lagged by 1 and 2 years, respectively, and

$\alpha _{2}$ denote the dependent variables lagged by 1 and 2 years, respectively, and

![]() $\beta _{1}$ and

$\beta _{1}$ and

![]() $\beta _{2}$ the parameters for anti‐pluralist government and citizen support, respectively. The main parameter of interest is

$\beta _{2}$ the parameters for anti‐pluralist government and citizen support, respectively. The main parameter of interest is

![]() $\beta _{3}$, denoting the interaction term of anti‐pluralist government and citizen support.

$\beta _{3}$, denoting the interaction term of anti‐pluralist government and citizen support.

![]() $\chi$ indicates a vector of control variables, and

$\chi$ indicates a vector of control variables, and

![]() $\mu _{i}$ and

$\mu _{i}$ and

![]() $\gamma _{t}$ country and year fixed effects, respectively. I lag all independent variables by 1 year because the effect of all of these variables on democratic development can be expected to be moderately delayed.Footnote 12 Furthermore, I standardize all continuous variables by a mean of zero and two standard deviations to facilitate the relative interpretation of coefficients (Gelman, Reference Gelman2008).

$\gamma _{t}$ country and year fixed effects, respectively. I lag all independent variables by 1 year because the effect of all of these variables on democratic development can be expected to be moderately delayed.Footnote 12 Furthermore, I standardize all continuous variables by a mean of zero and two standard deviations to facilitate the relative interpretation of coefficients (Gelman, Reference Gelman2008).

A critical assumption of the dynamic model defined above is that covariates are exogenous; that is, processes of backsliding do not have any effect on the independent variables such as citizen support or anti‐pluralist government. Since backsliding likely affects subsequent changes in these variables, I leverage a generalized method of moments (GMM) approach (Wawro, Reference Wawro2002). In this specification, more distant lags of the dependent variable are used as instruments while the two lagged variables by

![]() $t-1$ and

$t-1$ and

![]() $t-2$ remain on the right‐hand side of the regression equation. I use

$t-2$ remain on the right‐hand side of the regression equation. I use

![]() $t-3$ through

$t-3$ through

![]() $t-5$ as instruments, assuming that these values do not affect

$t-5$ as instruments, assuming that these values do not affect

![]() $Backsliding_{it}$ (cf. Claassen, Reference Claassen2020).Footnote 13

$Backsliding_{it}$ (cf. Claassen, Reference Claassen2020).Footnote 13

I restrict the data to those countries that have at least been an electoral or liberal democracy in 1 year between 1990 and 2019 and remove pre‐democracy observations.Footnote 14 This amounts to a dataset covering about 100 democracies over 29 years.Footnote 15

Statistical evidence

Patterns of citizen support, anti‐pluralist parties in power and democratic backsliding

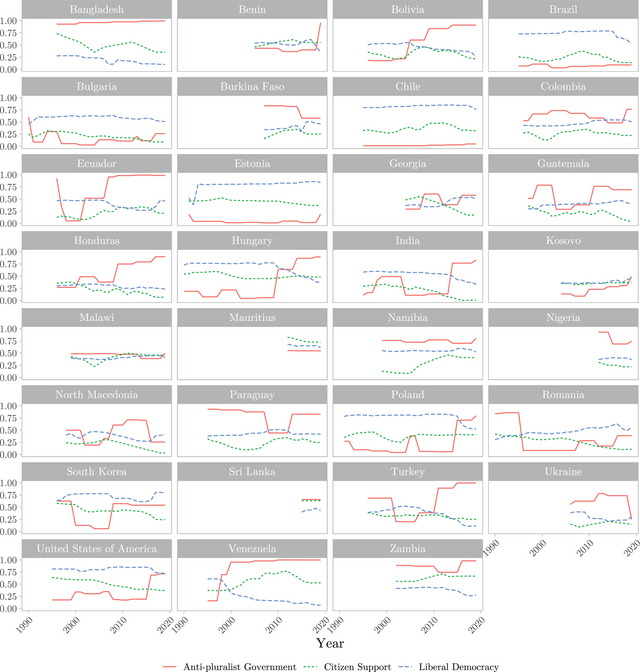

To begin with, Figure 1 displays the democratic trajectory of all countries that experienced a period of democratic backsliding between 1990 and 2019, along with citizen support for democracy and the anti‐pluralist parties in government indicators. Two general patterns can be observed. First, governmental parties' degree of anti‐pluralist orientation varies considerably over time in various countries, such as Hungary, India and Venezuela. In other countries, the level of government's anti‐pluralist behaviour has been comparatively constant (e.g., Estonia, Namibia).

Figure 1. Development of liberal democracy, anti‐pluralist parties in power and citizen support for democracies in countries with at least one downturn in liberal democracy in the highest quantile of a 20‐bin grouping since 1990. Only party scores with at least four expert coders are shown.

Regarding the trajectories of citizen support for democracy, several countries have witnessed a drop in citizen support for democracy during or even before periods of democratic backsliding. This pattern is evident in Brazil, Bulgaria, India, the United States and Romania, where there has been a decline in citizen commitment to democracy and stronger dominance of anti‐pluralist parties in government. Simultaneously, the level of democracy decreased, suggesting that public opinion, the composition of government and democratic trajectories follow parallel trends in some cases of democratic backsliding. However, a few countries deviate from this pattern, such as Bolivia and Venezuela, both of which witnessed an increase in public support for democratic governance when backsliding occurred. While these descriptive patterns allow for an overview of the development of the three main variables in question, the following section turns to the results of the TSCS models predicting democratic backsliding.

Are citizen support for democracy and anti‐pluralist parties in power related to democratic backsliding?

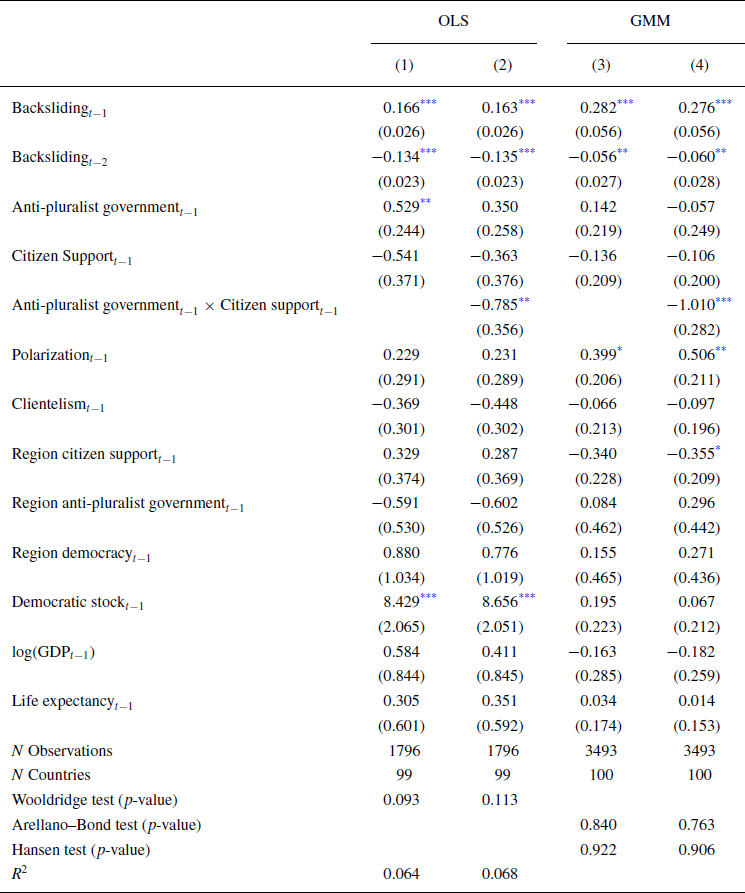

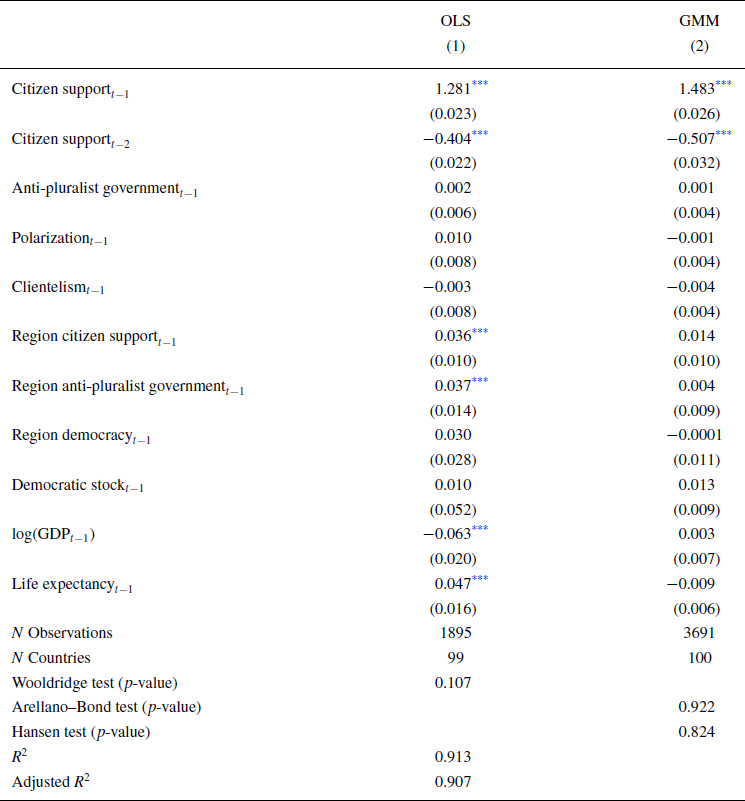

Table 1 reports the outcomes of the dynamic regression models predicting democratic decline. The Wooldridge test for serial correlation fails to achieve statistical significance, suggesting the absence of strong autocorrelation in the linear model. Similarly, the Hansen test for instrument validity and the Arellano–Bond test for second‐order correlation point to an adequately specified GMM model. Note that, in line with linear models similar to those employed by Claassen (Reference Claassen2020, SI 17), the variability in the outcome variable explained by the independent variables is fairly low. This can be attributed to the intentionally reduced variance in the outcome variable: given that the focus here lies on the independent variables predicting downturns in democracy, and since all instances of upturns are assigned a value of zero, the outcome variable displays less variance. As a result, the overall variation in the outcome variable explained by the independent variables is reduced by design.Footnote 16

Table 1. Dynamic TSCS models predicting downturn changes in liberal democracy

Abbreviations: GMM, generalized method of moments; OLS, ordinary least squares; TSCS, time‐series cross‐section.

*

p

![]() $<$0.1; **p

$<$0.1; **p

![]() $<$0.05; ***p

$<$0.05; ***p

![]() $<$0.01.

$<$0.01.

Note: Beck‐Katz panel corrected standard errors for linear models, and Windmeijer corrected standard errors for GMM models are reported. All independent variables are standardized by 2 standard deviations

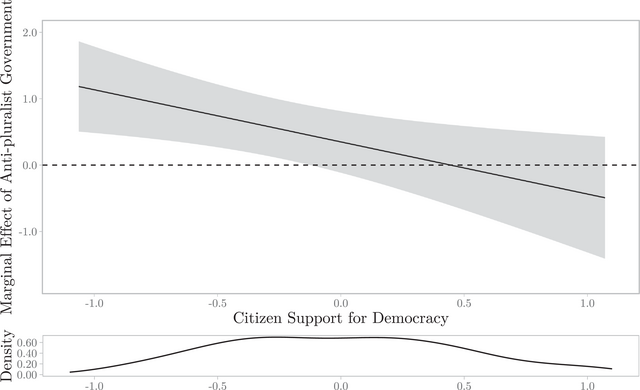

Model 1 includes anti‐pluralist government and citizen support for democracy as predictors alongside control variables, excluding the interaction term. This model shows that a stronger anti‐pluralist stance among governmental parties and a weaker commitment to democracy among citizens are associated with increased backsliding. With the introduction of the interaction term between anti‐pluralist government and citizen support (Model 2), the predictive strength of anti‐pluralist government and the negative relationship between public opinion and democratic backsliding remains. Simultaneously, the interaction of anti‐pluralist government and citizen support for democracy reveals a negative coefficient. Figure 2 shows the marginal effects of an anti‐pluralist government on democratic backsliding conditional on citizen support for democracy. This finding implies that a higher presence of anti‐pluralist parties in government, coupled with reduced citizen commitment to democratic ideals, is associated with subsequent backsliding. Another substantive predictor is democratic stock.

Figure 2. Marginal effect of anti‐pluralist government conditional on citizen support for democracy on democratic downturn (Model 2 in Table 1). 95 per cent confidence intervals are reported.

The GMM models produce consistent outcomes for the primary hypothesis but differ for certain other variables (Models 3 and 4 in Table 1). While anti‐pluralist government and citizen support do not appear to affect backsliding, the interaction effect between the variables turns out to be significantly negative. As in the linear models, a more anti‐pluralist government in conjunction with lower citizen support for democracy is associated with a more substantial decline in liberal democracy. All other variables do not turn out to be consistently statistically significant.

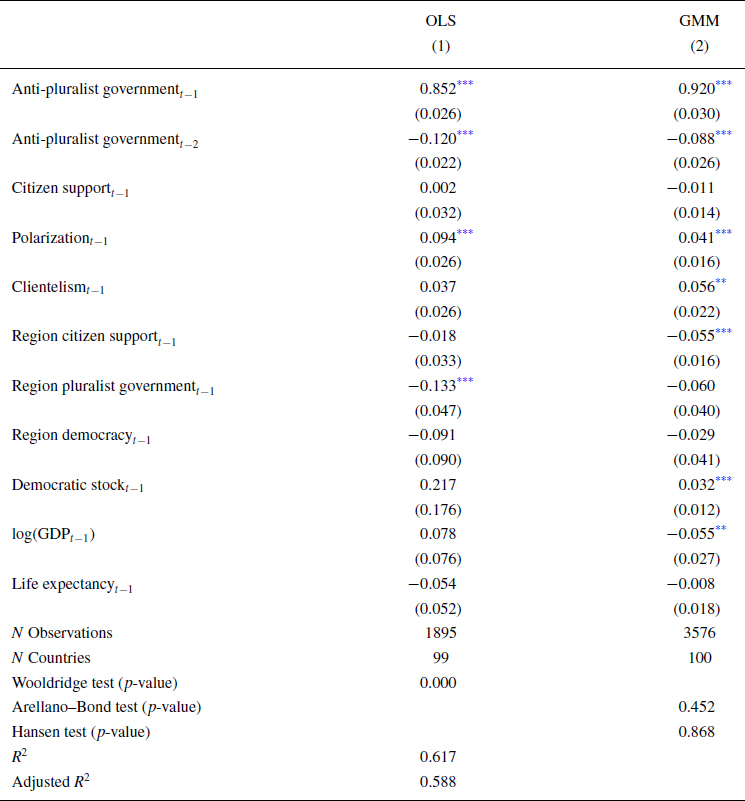

Is citizen support for democracy related to anti‐pluralist government rhetoric or vice versa?

While these results provide empirical support for the argument that anti‐pluralist governments can induce anti‐democratic institutional change most swiftly when citizen commitment to democracy is low, the question remains whether governments turn anti‐pluralist when citizen support for democracy declines: Does citizen support translate into party system change in the first place by affecting anti‐pluralist parties' chances to achieve governmental office?

To examine the relationship between citizen support and anti‐pluralist governments, I implement the following dynamic model, again both with OLS and GMM specifications:

Table 2 shows the results of the dynamic TSCS model predicting the level of anti‐pluralist governments.Footnote 17 As Model 1 (OLS) shows, higher citizen support is not associated with subsequent changes in the degree to which governments show anti‐pluralist conduct, but note that the Wooldridge test indicates autocorrelation in this specification. Model 2 (GMM) similarly does not suggest an effect of citizen support on anti‐pluralist governments.

Table 2. Dynamic TSCS models predicting anti‐pluralist parties in government

Abbreviations: GMM, generalized method of moments; OLS, ordinary least squares: TSCS, time‐series cross‐section.

*

p

![]() $<$0.1; **p

$<$0.1; **p

![]() $<$0.05; ***p

$<$0.05; ***p

![]() $<$0.01.

$<$0.01.

Note: Beck‐Katz panel corrected standard errors for linear models, and Windmeijer corrected standard errors for GMM models are reported. All independent variables are standardized by 2 standard deviations

Having found no evidence for an effect of citizen support for democracy on governmental parties' anti‐pluralist orientation, one may argue that anti‐pluralist governments are successful at making citizens less supportive of democratic ideals, hence dropping overall citizen commitment to democracy. This argument aligns with approaches that consider political elites to affect public opinion rather than vice versa. To test this proposition, I run the following dynamic TSCS model:

The results, however, do not provide empirical support for an elite effect on public opinion (see Table 3). Again, in the linear models, regional trends in anti‐pluralist governance and socioeconomic factors are related to subsequent changes in citizen support.

Table 3. Dynamic TSCS models predicting citizen support for democracy

Abbreviations: GMM, generalized method of moments; OLS, ordinary least squares; TSCS, time‐series cross‐section.

*

p

![]() $<$0.1; **p

$<$0.1; **p

![]() $<$0.05; ***p

$<$0.05; ***p

![]() $<$0.01.

$<$0.01.

Note: Beck‐Katz panel corrected standard errors for linear models, and Windmeijer corrected standard errors for GMM models are reported. All independent variables are standardized by 2 standard deviations

Robustness tests

In the spirit of Neumayer and Plümper (Reference Neumayer and Plümper2017), I implement a series of robustness tests to examine how measurement and modelling decisions may lead to similar or diverging results in the regression analysis.

Measurement uncertainty

A recent contribution has raised the potential issue of measurement uncertainty in latent trait modelling of public opinion (Tai et al., Reference Tai, Hu and Solt2024). However, there are various ways of taking account of measurement uncertainty, and, as Claassen (Reference Claassen2021) shows, the decision on how to incorporate uncertainty is as relevant as whether to incorporate it at all. To evaluate whether the main results are sensitive to the range of country‐level parameters obtained from the MCMC model, I iteratively run dynamic TSCS regressions with country/year estimates of citizen support from each parameter sample (see Online Appendix E.1). The results of both OLS and GMM specifications confirm a negative interaction effect as found in the main analysis with mean public opinion estimates. The regression estimates are consistently significant at the 90 per cent level for all more robust GMM specification and in 84 per cent of all models for the linear specification.

Alternative measures

In the results reported above, governments' anti‐pluralist orientation is measured by the mean of all parties' anti‐pluralist scores weighted by their seat share in the legislature. While this approach seeks to consider the effect of electoral systems on achieving political power in a given system, one might argue that the raw vote share in elections would be a better indicator to approximate each political party's dominance in a country's government. I compute an alternative indicator of anti‐pluralist governments (average anti‐pluralism scores of governmental parties weighted by vote share in the previous election) and rerun the TSCS model specification outlined in the empirical strategy. Similarly, I measure the anti‐pluralist government with the anti‐pluralism score of the head of the government's party. The findings are similar to the seat share measure, but the interaction estimate using the vote share measure is smaller in its effect size (see Online Appendix E.2).

Varying variable lags

Different lag structures of the independent variable might lead to diverging regression results. To test whether alternative structures yield different results from the 1‐year lagged independent variables (as defined in the main analysis), I implement a model with independent variables lagged by 2 years (see Online Appendix E.3). I also only vary the lag structure of citizen support for democracy while retaining a 1‐year lag of all other variables (including anti‐pluralist government).Footnote 18 Moreover, I run multiple models with randomly drawn lags between 1 and 2 years for all control covariatesFootnote 19 and all independent variables.Footnote 20 In all of these specifications, the interaction effect remains consistently negative.

Removing upper‐bound cases of backsliding

To see whether the severity of backsliding is related to the findings, I drop all countries from the analysis that experienced a downturn in the 100th percentile of the overall distribution (Online Appendix E.4). Removing these countries reduces the effect size, but the overall pattern remains the same. Given that countries such as Brazil, Hungary and Venezuela are among the countries falling into the group of countries with observations in the 100th percentile, the reduced effect size may be explained by the absence of prominent cases of backsliding in this analysis.

Dropping regions

To evaluate whether a subset of democracies mainly drives the results, I remove each region (e.g., Southern Africa, Central America) from the sample once at a time (see Online Appendix E.5). The interaction coefficient retains its negative effect in all models, suggesting that the main finding holds irrespective of which region is removed from the analysis. By contrast, the relationship between citizen support and anti‐pluralist governments is consistently null across models.Footnote 21

Different covariate combinations

Lastly, since the interaction effect may be affected by whether or not additional variables are added as predictors to the TSCS models, I rerun the OLS and GMM models reported above with all possible covariate constellations (see Online Appendix E.6). Irrespective of which constellation of additional independent variables enter the regression equation, the interaction effect between citizen support for democracy and anti‐pluralist government retains its significance across all models. A different picture emerges regarding the relationship between citizen support for democracy and anti‐pluralist governments and vice versa. In some GMM specifications, stronger citizen support for democracy is marginally negatively associated with anti‐pluralist government orientation. Similarly, in some OLS specifications, anti‐pluralist governments are slightly positively related to citizen support for democracy. These inconclusive findings are in contrast to the consistent interaction effect between government and citizen support in the models predicting a democratic downturn.

Non‐parametric estimator

Following Hainmueller et al. (Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2019), I use a binning estimator, which groups the citizen support for democracy scores in three subgroups (upper, median and higher tercile) and estimates the marginal effect of anti‐pluralist government on the downturn in democracy for the median public opinion value of each subgroup. I also implement a model with a non‐parametric Kernel estimator (see Online Appendix E.7). These alternative estimators support the linearity assumption of the interaction term.

Conclusions: Safeguarding democracy beyond voting

Although anti‐pluralist parties openly question the integrity of their political contenders and disapprove of democratic norms (Linz, Reference Linz1978; Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018), many, but not all, of these anti‐pluralist parties induce severe democratic backsliding when in government (Medzihorsky & Lindberg, Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024). Why do we observe these diverging outcomes? I argue that anti‐pluralist governments are more reluctant to undermine democratic institutions when they are faced with a society firmly committed to democracy. In such settings, anti‐pluralist parties in power face a high risk of voter punishment in the next election and public backlash, such as large‐scale protests, that may harm the government's popularity. Conversely, if citizen support for democracy is weak, anti‐pluralist actors in government have less to fear in terms of detrimental electoral consequences and dropping public support. Consequently, in societies where citizens are less supportive of democratic governance, democratic backsliding is more likely to occur.

The results of a TSCS analysis from 1990 to 2019 align with this argument: political systems are more likely to witness democratic backsliding when anti‐pluralist governments operate in a society where public support for democracy is weak. Meanwhile, citizen support for democracy is unrelated to changes in anti‐pluralist government or vice versa. However, it is important to note that two cases of backsliding, Bolivia and Venezuela, deviate from this overall pattern: In these countries, citizen support for democracy grew shortly before and during the backsliding sequence.Footnote 22 Whether this is because the governments in these two countries disseminated the narrative that their reforms strengthen democracy or citizens become more supportive of democracy as they realize that it is under threat, future scholarship may investigate how citizen attitudes towards democratic governance change during times of democratic backsliding.

This study holds implications for the conditions under which democracies are either vulnerable or more resilient. Despite scholarly concerns regarding social desirability bias when surveying citizens about democracy (Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020), a relevant finding of this study is that more robust support for democracy, as indicated by responses in public opinion surveys, seems to create an environment in which anti‐pluralist incumbents are less inclined to undermine democracy. Consequently, democratic institutions are more likely to endure even in the presence of anti‐pluralist parties in power, provided that most citizens align with democratic values while rejecting authoritarian governance and unconstrained leadership. Alongside the positive influence of citizen support for the democratization of political systems (Claassen, Reference Claassen2020; Welzel, Reference Welzel2007), disseminating democratic beliefs among citizens in both new and established democracies could safeguard liberal democracy from the extent of decay that anti‐pluralist parties in power could cause. As Bermeo (Reference Bermeo2003, p. 254), writing about the prospects of democracy in the 21st century, already noted prior to the recent debate on the origins of democratic backsliding:

More people prefer democracy to dictatorship, a strengthened civil society is better able to express these preferences, and political elites have better information about just what people's preferences are. However, caution and vigilance are still very much in order. The expanded mass media can be used for ill purposes as well as good; anti‐democratic leaders can replace Left‐Right polarities with religious, ethnic, and regional polarities instead; the embrace of democracy is very far from universal, and our more densely organized civil societies can still contain fundamentally anti‐democratic elements.

These insights remain relevant today. Despite widespread citizen support for democracy, there is potential for this support to evolve into a preference to weaken checks and balances for the sake of government efficiency, particularly during crises (Gratton & Lee, Reference Gratton and Lee2024). However, even when anti‐pluralist parties attain power and gain the means to undermine democratic institutions, public support for democracy can constrain their efforts to execute their anti‐pluralist agenda. Meanwhile, citizens represent just one facet of constraint on the executive. Future research could further investigate how other constraints, such as those originating from different branches of government like the judiciary or international organizations, might increase the costs for anti‐pluralist governments aiming to target democratic institutions, thereby potentially reducing the risk of democratic backsliding.

Certainly, the risk to democracies would be reduced if anti‐pluralist governments were not to assume power initially. However, as previous research has demonstrated (Carey et al., Reference Carey, Clayton, Helmke, Nyhan, Sanders and Stokes2022; Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Stolle and Bergeron‐Boutin2022; Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020), many citizens who fundamentally value democracy would still vote for their preferred candidates and parties, even in cases of undemocratic conduct. And yet, as this study suggests, even if citizens are reluctant to remove undemocratic governments from office, their commitment to democratic governance appears to constrain their governments. Thus, even when anti‐pluralist parties attain governmental power, democracy is not inherently destined to decline but can still be safeguarded by a public that embraces democracy as its preferred form of government.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Chris Claassen, Mark Dawson, Kristian Frederiksen, Sebastian Hellmeier, Sebastian Juhl, Anton Könnecke, Barton Lee, Hans Lueders, Monika Nalepa, Greta Schenke, Frank Schimmelfennig, Benjamin Smith, Milan Svolik, Henry Thomson, Natasha Wunsch and the anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on previous versions of the manuscript. I am grateful to Amanda Edgell for sharing data on democratic stock variables. I am also indebted to audiences at APSA, DVPW, EPSA and MPSA Conferences and the Hertie School Berlin/ETH Zurich Workshop for feedback. This research was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (PZ00P1_185908).

Open access funding provided by Eidgenossische Technische Hochschule Zurich.

Data availability statement

The data and materials required to verify the computational reproducibility of the results, procedures and analyses in this article are available on the Harvard Dataverse Network, at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SVBACA.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Online Appendix.