On January 6, 2021, 139 Republican members of the House of Representatives voted to object to the count of the 2020 Electoral College ballots during a joint session of Congress, hereafter referred to as ‘objectors’. This vote occurred just hours after the violent insurrection in the US Capitol, prompting a strong reaction from the business community. In a statement after this assault on the peaceful transfer of power, National Association of Manufacturers President Jay Timmons criticized Republicans stoking Trump’s claims of voter fraud, which led to both the insurrection and the vote to overturn election results, saying, ‘Throughout the whole disgusting episode, Trump has been cheered on by members of his own party, adding fuel to the distrust that has enflamed violent anger’ (National Association of Manufacturers 2021). America’s largest corporations followed suit. During the period after January 6, 38 per cent of Fortune 500 company PACs announced they would temporarily suspend PAC operations, and many other companies issued public statements or unofficially suspended PAC operations without formally announcing a pause. Such efforts led to lower levels of financial support among corporate PACs in the first year of the 2022 election cycle, especially among corporations with a large share of Democratic-leaning employees (Li and Di Salvo Reference Li and Di Salvo2022). However, over the course of the 2021-2022 election cycle, most PACs resumed contributions to at least some candidates.

This project explores how support for overturning the 2020 election results impacts the relationship between major companies and Republican members of Congress. While PACs associated with ideological interest groups use contributions to support candidates who align with their values, business-oriented groups typically use their financial resources to gain access to lawmakers they aim to influence (Powell and Grimmer Reference Powell and Grimmer2016). We argue that businesses try to balance the competing demands for access to policymakers with stakeholders’ desire to hold lawmakers accountable for their attacks on U.S. democracy. Business groups navigate this trade-off by advancing a company’s political interests through continued relationships with members of Congress while also decreasing their contributions to those who undermine democratic norms. Corporations strike this balance because they are sensitive to the preferences of key stakeholder groups – including shareholders and company employees, especially those who are eligible to give to the PAC. While PACs have previously faced decisions about whether to support candidates under ethics investigations or those violating congressional and professional norms, these situations have been relatively limited in scope. The events of January 6, however, offer a unique opportunity to observe this trade-off on a much broader scale.

The efforts of Donald Trump and his allies in the weeks leading up to the storm on the Capitol represent a grave disruption of democratic norms, defined as ‘… informal rules that, though not found in the constitution or any other laws, are widely known and respected’ (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018, 110) and that serves as a ‘… shared understanding of appropriate behavior’ (Donno Reference Donno2013, 4) in democracies. As a highly salient event of historic proportions, we expect companies to decrease their PAC expenditures to those who objected to the 2020 election result while continuing to give to those who can influence the interest group’s policy priorities. We examine these questions by using Fortune 500 Company PAC contributions to Republicans in the wake of the January 6 insurrection. We chose Fortune 500 companies for three primary reasons: the companies use access-oriented strategies to advance their public policy agendas, PACs pay close attention to their public image and want to be perceived as a socially responsible ‘corporate citizen’ (Gawehns and Meli Reference Gawehns and Meli2022), and these large corporations have the financial resources to contribute to objectors if they would like to do so. The size of Fortune 500 firms makes it likely that employees, shareholders, and other stakeholders represent a cross-section of the national electorate and their political preferences. In addition, they tend to have large PACs that can afford to make contributions to a variety of candidates. During the 2022 election cycle, 285 (88.51 per cent) of the 322 active Fortune 500 PACs raised more than $50,000. The middle 50 per cent of Fortune 500 PACs raised between $131,492 and $796,805, which means that most Fortune 500 PACs are able to contribute to a variety of candidates. A non-contribution to an objector therefore represents a choice rather than a financial constraint. If we are correct about the trade-offs businesses face, then we should see Fortune 500 companies adjust their PAC giving by decreasing the amount they contribute to those who threaten democracy.

We employ a difference-in-differences design to examine contribution patterns for the 2018, 2020 and 2022 election cycles, which provide important variation in majority control of Congress. We find that after January 6, Fortune 500 PACs responded to pressure from stakeholder groups by reducing their contributions to those Republicans who supported Trump’s election claims in Congress. Results reveal that Republican members of Congress who voted to uphold the 2020 election results receive, on average, $129,230 more in Fortune 500 PAC contributions than someone who voted to overturn. Notably, this financial penalty for objectors is comparable in magnitude to those retiring from Congress. We also find that party and committee leadership positions remain strong predictors of PAC contributions, providing support for our thesis that corporate America faces a balancing act regarding its two audiences. We provide evidence that objectors on key committees and in party leadership receive fewer total contributions from Fortune 500 PACs compared to non-objectors in similar positions.

These results have important implications for our understanding of the trade-off corporations face. We demonstrate that while businesses continue to value access to high-level lawmakers, they also bend to internal and external pressure to adjust their campaign finance activities when those in power threaten democratic norms. Risking their ability to build relationships with key policymakers, we observe that Fortune 500 PACs divert money away from objectors. In doing so, corporations act not only in their economic interests by gaining access to politicians through political donations, but also as a vehicle for Americans eager to support democracy. Taken together, our results indicate that big businesses are responsive to pressures beyond mere economic benefit, leading them to take calculated risks in their political strategies.

Why Do PACs Contribute to Candidates for Congress?

After years of debating whether PACs represented a quid pro quo with members of Congress – a theory that yielded null results in repeated studies (Baldwin and Magee, Reference Baldwin and Magee2000; Wawro, Reference Wawro2001; Roscoe and Jenkins, Reference Roscoe and Jenkins2005) – political scientists settled on an alternative explanation for interest groups’ support for congressional candidates. Instead of ‘buying votes’, scholars theorize that PAC contributions are a means to gain access to members of Congress (Sorauf Reference Sorauf1992; Wright Reference Wright2002).

Access serves corporate goals in several ways. For instance, Hall and Wayman (Reference Hall and Wayman1990) find that PAC contributions have a greater impact on issue involvement at the committee level than on floor votes. In addition, PAC contributions are more effective when the company has a presence in the district of the legislator receiving the contribution. Snyder (Reference Snyder1992) sees PAC contributions as ‘long-term investments’, enabling interest groups to maintain access to incumbent members of Congress through consistent support of specific lawmakers. PAC contributions also help legislators identify which groups are most likely to provide valuable information (Wright Reference Wright2002). As a result, corporate actors who value access employ one of two strategies: contributing to members of Congress with whom they share interests to reinforce existing relationships and contributing to those with whom they have little in common to establish new common ground (Wright Reference Wright2002).

Those in the business community, in particular, use access-oriented strategies to accomplish legislative and regulatory goals, while other groups contribute in order to elect ideological allies (Fox and Rothenberg Reference Fox and Rothenberg2011). Those who are access-oriented are more likely to give to incumbents compared to ideologically motivated groups (Fouirnaies and Hall Reference Fouirnaies and Hall2014). For example, interest groups are more likely to get meetings with legislators to whom they make PAC contributions (Kalla and Broockman Reference Kalla and Broockman2016), and members of Congress who are connected to the same lobbyists are likely to have similar voting records (Victor and Koger Reference Victor and Koger2016). In sum, there is considerable evidence that long-standing relationships can facilitate access to key legislators, reinforcing the notion that interest groups, particularly big businesses, adopt a ‘pragmatic’ approach to campaign contributions. This strategy aligns with Bauer, Pool, and Dexter’s (Reference Bauer, Pool and Dexter1964) findings from over half a century ago, emphasizing the pursuit of policy goals through strategic financial support.

While previous studies have provided evidence of a relationship-oriented connection between big businesses and members of Congress through PAC contributions, few have considered the potential consequences of undesirable behaviour by lawmakers on corporations’ ability to maintain their pragmatic approach to lobbying and political contributions.

The Limits of Pragmatism: Big Businesses & Norm Violations

We argue that businesses attempt to balance their access-based strategy with pressures from their stakeholders, in particular shareholders and employees who are eligible to contribute to the PAC, such as executives and the lobbyists themselves. To examine whether corporate PACs act strategically when facing norm violations by elected officials, we focus on Fortune 500 companies that have federal PACs making contributions to candidates for the U.S. House of Representatives. These companies see contributions primarily as an entry ticket to the halls of Congress.

Previous studies have shown that stakeholders and organized interests influence each other, for example, by using political contributions as a signal to voters, similarly to the way some groups use endorsements (Ainsworth and Sened Reference Ainsworth and Sened1993). In this way, the organizations behind PACs aim to influence their members’ support for candidates for office. This relationship can work in the other direction as well, with interest groups responding to the desires of their members to maintain internal support for the group’s political programs. As with other interest groups, businesses aim to minimize potential conflicts between members and the organization’s goals and actions.

We argue that corporate PAC contribution strategies are sensitive to strongly held preferences of employees and shareholders, especially those who are eligible to give to the company’s PAC (see also Li Reference Li2018). Federal law establishes that corporate PACs, technically known as Separate Segregated Funds, may solicit contributions from the company’s executive and administrative personnel, which typically includes executives, managers, administrative employees, and professional employees, including the government affairs team (Federal Election Commission 2022). PACs rely on voluntary donations from this group of employees to sustain the PAC. As a result, these employees’ preferences are taken into account when the PAC makes contribution decisions.

We can observe how corporate PACs respond to concerns of PAC-eligible employees. According to a recent survey of corporate PACs, 85–90 per cent maintain either formal or informal contribution guidelines as part of their PAC bylaws to provide transparency about their decision-making processes (Public Affairs Council 2021). Of the groups that have contribution guidelines, 63 per cent list character, ethics, or reputation as criteria for PAC contributions (Public Affairs Council 2021). Traditionally, cases of personal corruption have dominated considerations of potentially undesirable behaviour, but January 6th brought attention to the violation of democratic norms as another form of problematic conduct. After January 6, several PACs placed new restrictions on contributions based on support for democratic principles or integrity-related criteria (Public Affairs Council 2021).

In addition to constraints written into bylaws, PACs use transparency as an accountability tool. Many PACs publish annual reports that contain lists of the contributions the PAC makes to all candidates (Public Affairs Council 2021). Some companies, including Coca-Cola, even publish their PAC contributions on their corporate websites (Coca-Cola Corporation Reference Corporation2022). These practices were adopted by PAC directors in response to calls for accountability by PAC-eligible employees and other stakeholders,Footnote 1 and demonstrate that employees and shareholders care about the PAC’s choices, are involved in the PAC’s decision-making, and that companies are responsive to their employees’ concerns about PAC contributions. These realities support Ainsworth and Sened’s (Reference Ainsworth and Sened1993) theory of two interest group audiences. PACs operate as a link between their principals and government officials, and they aim to balance the demands of these distinct audiences. The events of January 6 present corporate America with an opportunity to translate its pro-democracy attitudes into political action through targeted campaign donations.

In addition to PACs’ administrative procedures, we can also observe changes in PAC contribution behaviour in response to members of Congress dealing with controversy. For example, former Representative Duncan Hunter was a Republican member of Congress who received heavy support from corporate PACs until he was indicted for falsifying campaign finance records and using political contributions to pay for personal expenses (Open Secrets Reference Secrets2022; Thornton Reference Thornton2018). After Hunter was indicted at the end of the 2018 election cycle, PAC contributions dropped precipitously. However, it is impossible to determine whether the drop occurred due to Hunter’s anticipated resignation from Congress or his unethical behaviour. Therefore, a more systematic study is needed.

January 6: A Case Study in Big Business and Democracy

The events around January 6 provide a high-profile test for our theory of cross-pressured business interests. While controversies involving members of Congress have tended to be isolated incidents, nearly two-thirds of House Republicans voted to object to election results in one or more states, challenging previous individualized views of ethics violations. Donald Trump’s attempt to stay in office violated the fundamental democratic norm that election results are accepted by those competing for power (‘losers’ consent’, see Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005), thereby eroding citizens’ trust in elections (Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Davis, Nyhan, Porter, Ryan and Wood2021; Howe Reference Howe2017) and further politicizing constitutional norms in the USA (Kingzette et al. Reference Kingzette, Druckman, Klar, Krupnikov, Levendusky and Ryan2021). Republicans’ support for Trump’s efforts also speaks to the rising concern about the robustness of democratic norms in Western democracies (Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Davis, Nyhan, Porter, Ryan and Wood2021; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Saikkonen and Christensen Reference Saikkonen and Christensen2023; Wuttke, Schimpf and Schoen Reference Wuttke, Schimpf and Schoen2020).

January 6 not only represents a serious crisis in the American political system but also a highly salient event for corporations, their employees, and shareholders. In addition to intense media coverage, PAC managers and political directors received an extraordinary amount of feedback from eligible employees in the aftermath of January 6. Corporate public affairs departments also handled inquiries from CEOs and other C-suite executives. This pressure, not to mention government affairs managers’ own reactions to the insurrection, led to PAC pauses, bans on contributions to objectors, changes to PAC bylaws, and a variety of other new constraints.Footnote 2

After January 6, PACs faced a trade-off between their desire to represent their members’ interests by maintaining contacts with policymakers on one hand, and stakeholders’ aversion to blatant violations of democratic norms such as subverting trust in elections on the other. Balancing these competing interests meant pausing, reducing, or possibly ceasing contributions to those involved on January 6. A complete stop of all contributions would jeopardize the core purpose of campaign contributions – access to lawmakers. However, not reacting to the events would alienate key company stakeholders.

Hypotheses

As a result of these cross pressures, we expect Fortune 500 PACs to maintain their access-oriented strategy but decrease their contributions to those members of Congress who objected to the 2020 election results. It is, however, not enough to compare contributions to objectors and non-objectors in the election cycle following January 6. To see whether this pattern represents a change in behaviour, we need to analyze how contribution patterns changed between objectors and non-objectors before and after January 6.

Hypothesis 1: Unlike non-objectors, objectors will receive fewer total contributions from Fortune 500 company PACs after January 6 than they did in the two election cycles prior to January 6.

Party leaders tend to receive more financial support than rank-and-file members. This is because having access to House and Senate leadership comes at a premium for businesses seeking to leverage leaders’ agenda-setting and policy-making power (Romer and Snyder Reference Romer and Snyder1994). However, we expect objections to the 2020 election results to constrain the extent to which Fortune 500 PACs support leaders. The ‘leader premium’ for objectors should decrease accordingly.

Hypothesis 2: Party leaders who voted to object to the 2020 election results will receive less of a financial advantage over non-objectors in similar positions after January 6.

Similarly, political science literature predicts that organizations pursuing an access-oriented strategy will seek involvement from members of key committees (Hall and Wayman Reference Hall and Wayman1990). For the purposes of this study, we designate as ‘key committees’ those identified by Bernhard et al. (Reference Bernhard, Sewell and Sulkin2017): Appropriations, Energy and Commerce, Ways and Means, and Rules. We expect that objections to the 2020 election results will constrain the extent to which Fortune 500 PACs support members of these committees.

Hypothesis 3: Members of key committees who voted to object to the 2020 election results will receive less of a financial advantage over non-objectors in similar positions after January 6.

Data and Method

Data were collected using bulk download files available from the Federal Election Commission (FEC). All contributions from Fortune 500 companies to House Republicans during the 2022 cycle, with just one exception, occurred after January 6, 2021. This means that nearly all contributions took place after the cut point in our model. We include contributions to a member of Congress’s re-election committee, leadership PACs operated by members of Congress, and independent expenditures made by PACs to support members of Congress. Our goal is to understand how objections to the 2020 election results – along with access-related variables – influence the total contributions Republican members of Congress receive from Fortune 500 PACs. We first use OLS estimates to establish the total contribution amounts for objecting and non-objecting Republicans during the 2021-2022 election cycle, followed by a difference-in-differences design to account for contributions to objectors and non-objectors over time.

Dependent Variable: The outcome variable for all hypotheses is total contributions in thousands. To create this variable, we calculate the aggregate amount in thousands of dollars individual Republican members of Congress received from Fortune 500 PACs during the 2021-22 election cycle. The mean contribution amount to Republicans from Fortune 500 companies during the 2022 election cycle is just under $200,000. The median is $140,500, indicating a number of outliers at the high end of the distribution. For difference-in-differences models, we also include total contributions in thousands for the 2017-2018 election cycle and for the 2019-2020 election cycle. The 2017-2018 cycle provides important variation in majority control of the House of Representatives. We conducted the analysis using inflation-adjusted contributions per cycle, with 2022 US dollars as a baseline and adjustments for 2020 and 2018 based on changes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Using non-adjusted contribution data does not change the results in a substantive way.

Independent Variable: The key independent variable is an indicator variable for Republicans who formally objected to the constitutionally required count of Electoral College ballots from Arizona, Pennsylvania, or both during the joint session on January 6 and 7, 2021 (vote #10 and #11 of the 117th Congress). These objections were part of Donald Trump’s efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election. Congress adjourned twice to debate the objections but ultimately voted them down. One hundred and thirty-nine Republicans – roughly two-thirds of the GOP conference – objected to the election and are coded with a 1; seventy-six (35.5 per cent) Republicans did not vote to object to the election results and are coded with a 0. Objector status is used as the treatment variable in difference-in-differences models.

To understand other reasons why corporate PACs might support a member of Congress, we include variables for committee leaders (committee ranking members in 2021), subcommittee leaders (subcommittee ranking members in 2021), party leadership (including speaker, majority/minority leader, majority/minority whip, chief deputy whip, conference chair, and NRCC chair), and membership on the ‘big four’ committees: Appropriations, Energy and Commerce, Rules, and Ways and Means. We include these access variables for members of Congress based on their position in December 2021, which represents the approximate midpoint of the election cycle.

We also include a dichotomous variable for members in competitive districts to account for the fact that interest groups give more money to candidates in competitive races (Ballard, Hassell and Heseltine Reference Ballard, Hassell and Heseltine2021; Bonica Reference Bonica2013). The districts included are those with an absolute value of district partisan lean smaller than 9, using the Cook Political Report’s PVI score (Wasserman Reference Wasserman2021). We also include DW-NOMINATE scores as distance from the chamber median to control for ideological extremity as a possible confounding variable, as well as the number of terms served in Congress as a measure of seniority. In addition, we add a variable for members who retired at the end of 2022 or ran for another office during the 2022 election cycle since those members are less likely to receive contributions to their House campaigns (McCarty, Poole and Rosenthal Reference McCarty, Poole and Rosenthal2016). We also conducted robustness checks included in the online supplementary material to rule out the possibility that retirements had an impact on the main variables of interest. There is no statistically significant difference in district competitiveness between retiring versus non-retiring Republican House members.Footnote 3 However, the difference in DW-NOMINATE scores is statistically significant, with retiring Republicans being more moderate than non-retiring Republicans.Footnote 4 We do not find that more moderate Republicans received a fundraising advantage.

To evaluate our hypotheses across election cycles, we employ a difference-in-differences design in order to examine whether objecting Republicans received fewer contributions after January 6 compared to the trends prior to January 6, 2021. The difference-in-differences model allows us to compare the outcome (contributions) before and after the ‘treatment’ (voting to object on January 6) while controlling for changes in majority status, committee assignments and leadership positions of members of Congress. Our goal is to understand how objections to the 2020 election results – along with access-related variables – influence the total contributions Republican members of Congress receive from Fortune 500 PACs.Footnote 5

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for those who were members of the 115th Congress (2017-2018) and continued to serve during the 117th Congress (2021-2022). Those who voted to object on January 6 – our ‘treatment group’ – were more conservative and came from safer districts. Objectors were also less likely to receive corporate donations in the first place, a finding first discussed by Miller and Bates (Reference Miller and Bates2023).

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Objectors and Non-Objectors (115th Congress)

To construct our panel data, we use contribution data from the 2017-2018, 2019-2020, and 2021-2022 election cycles. Each cycle begins in January of the previous year (for example, 2021 for the 2022 cycle) and ends in December of the election year. Since PACs budget their contributions to candidates based on election cycles, it is important to group these contributions by their two-year cycle instead of by year. Our unit of analysis is the Member of Congress by-election cycle. The dependent variable is total contributions in thousands for the election cycle, with each member of Congress having three entries in the dataset – one each for the 2018, 2020, and 2022 cycles. We omit any member of Congress who was not in office during all three periods. The key independent variable for Model 2 is an interaction between objector status and a variable indicating whether the election cycle took place after January 6 (‘Period’). We control for the same variables as in the OLS model (retiring, ideology, competitive seat, seniority, and access-oriented variables). Additional interactions allow us to account for differences in Fortune 500 contributions before and after January 6 for members of key committees and leaders who objected or did not object to the election results. We include legislator (unit) fixed effects in models that span multiple election cycles.

Results

Before analyzing the relationships between our independent and dependent variables, we begin by reviewing the descriptive statistics. Figure 1 displays the observed Fortune 500 PAC contributions to objectors and non-objectors across various positions during the 2022 cycle. As shown, Fortune 500 companies contributed significantly more to Republican legislators who voted to uphold the 2020 election results, providing initial support for our hypotheses. By contrast, objectors in key committee roles and leadership positions saw a notable decrease in fundraising totals, despite their influential status. Figure 1 also suggests that holding key positions serves as an important mediating variable in the relationship between contribution amounts and objector status.

Figure 1. Aggregate Contributions to Republicans During the 2022 Election Cycle.

Model 1 in Table 2 provides OLS results for the 2022 cycle. Results indicate that, after controlling for access-oriented variables, objectors will receive less financial support from Fortune 500 companies compared to non-objectors. The difference between objectors and non-objectors is substantively significant – objectors are expected to receive approximately $196,000 less in total PAC contributions from Fortune 500 companies. This penalty surpasses that of retiring members of Congress, who the model predicts will receive $142,000 less than their non-retiring counterparts. The magnitude of this ‘objector penalty’ is unexpected.

Table 2. Predictors of Fortune 500 PAC Contributions

Note: * < 0.05 (two-tailed). Model 1 uses total PAC contributions from all Fortune 500 PACs in the 2021-2022 congressional election cycle as the dependent variable (in thousands of dollars). The unit of analysis for Models 2 and 3 is Republican members of Congress in each election cycle (includes 2018, 2020, and 2022 election cycles), with standard errors clustered by member of Congress. Data from 2017-2018 and 2019-2020 have been adjusted for inflation. The dependent variable for Models 2 and 3 is the election cycle total contributions from Fortune 500 PACs.

In addition, OLS results indicate that committee leaders, party leaders, and key committee members will receive more financial support from Fortune 500 companies compared to those who do not serve in those key positions. These findings are in line with previous research emphasizing positions of power as sources of lawmaking effectiveness (Volden and Wiseman Reference Volden and Wiseman2014) and targets of interest group behaviour (Romer and Snyder Reference Romer and Snyder1994). Meanwhile, subcommittee ranking member status, seniority, ideology, and district competitiveness do not have a statistically significant impact on Fortune 500 PAC contributions during the 2022 election cycle. In sum, the effect of objector status on 2022 fundraising totals is large enough to offset traditional access-oriented positions like membership on key committees and is nearly large enough to offset being a committee leader.

While OLS estimates suggest a relationship between objector status and PAC contributions, they do not take preexisting patterns of campaign contributions into account. We therefore focus on changes over three election cycles in order to exclude alternative explanations for the drop-off in funding. The difference-in-differences estimates in Model 2 of Table 2 provide support for Hypothesis 1. The statistically significant interaction term between objector status and period (2022 cycle) indicates that objectors receive fewer contributions from Fortune 500 PACs compared to non-objectors following January 6, in contrast to the two previous election cycles. The model estimates that, after controlling for other variables, objectors will receive $129,230 less in total contributions from Fortune 500 companies. Remarkably, this penalty is comparable in magnitude to those for retiring members of Congress, which is estimated to be $149,550. Additionally, the model predicts that, all else being equal, members of key committees receive $160,590 more in total contributions from Fortune 500 companies compared to Republicans not on Appropriations, Rules, Ways and Means, and Energy and Commerce. Additionally, even after controlling for objector status, members of Congress who are more distant from the chamber’s mean ideology score will receive fewer contributions from Fortune 500 company PACs compared to those who are closer to the chamber’s mean ideology. The model predicts no fundraising advantage for party leaders and non-party leaders, committee leaders, and subcommittee leaders.

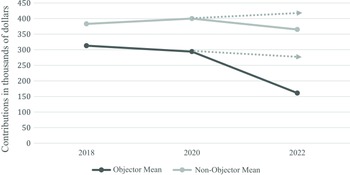

The parallel trends assumption (PTA) in DiD designs posits that, in the absence of treatment, the average outcomes for both the treated and control groups would have evolved in a parallel manner (Roth et al. Reference Roth, Sant’Anna, Bilinski and Poe2023). Accordingly, we include Figure 2 to graph the inflation-adjusted differences between objector and non-objector means over three election cycles. Contributions to objectors were already decreasing prior to January 6, while contributions to non-objectors were trending up, not consistent with the PTA. After January 6, however, the trends diverged sharply, with contribution totals to Republican objectors plummeting and contributions to Republican non-objectors slightly decreasing compared to the inflation-adjusted number of previous cycles. Non-objectors saw a slight increase from 2018 to 2020, followed by a decrease in inflation-adjusted contributions from 2020 to 2022. By contrast, objectors saw a slight decrease from 2018 to 2020, followed by a sharp drop after January 6, 2021. We include a non-inflation-adjusted chart in the supplementary materials.

Figure 2. Mean Contributions to Objecting and Non-Objecting Republicans by Election Cycle (inflation-adjusted).

To further investigate the impact of pre-existing trends, we conducted a two-cycle difference-in-differences model as a placebo test, which is included in Table S2 in the supplementary material. In this DiD model, data from 2018 and 2020 are used, with an interaction between objector status and an indicator for the 2020 cycle. The results indicate a positive and statistically significant difference between objectors and non-objectors prior to January 6, which undermines the parallel trends assumption. However, the coefficient (-32.57) is substantively smaller than the one found in the three-cycle analysis (-129.23), suggesting a four-fold increase in the magnitude of the objector-non-objector difference during the 2022 cycle.

Given the result of the placebo test, we added a third model with an additional interaction between election cycle and objector status to Table 2. The model confirms that after accounting for separate time trends for objectors and non-objectors, the effect of objector status on contributions is still significant and larger than in previous estimates. This suggests that even after considering pre-existing trends, objector status remains a strong determinant of campaign contributions. Importantly, most of the variation in contributions due to objector status is captured by the interaction between objector status and treatment period (2022 cycle).

How does objector status interact with key variables of congressional influence? Table 3 provides results for a three-way interaction to understand the interplay between objector status and leadership positions as hypothesized in H2. Hypothesis 2 posits that party leaders who are objectors will experience a smaller financial advantage compared to non-objector leaders following January 6. The model results provide support for this. Figure 3 indicates that prior to January 6, objecting leaders and non-objecting leaders received similar levels of support from Fortune 500 PACs, but that the level of support for objectors drops precipitously during the 2022 cycle (including controls). In comparison, non-objecting leaders are expected to receive similar levels of support before and after January 6. In sum, January 6 resulted in a substantively significant reduction in Fortune 500 campaign contributions for party leaders who objected to the 2020 election results.

Table 3. Predictors of Fortune 500 PAC Contributions – Conditional on Objector Status and Leadership

Note: * < 0.05 (two-tailed). Models are fixed effects on members of Congress with robust standard errors. The dependent variable is the inflation-adjusted total PAC contributions in thousands of dollars.

Figure 3. Marginal effects of leadrership.

Hypothesis 3 makes similar predictions about objecting and non-objecting members of key committees. Figure 4 indicates that these two groups received similar levels of support from Fortune 500 companies prior to January 6. During the 2022 cycle, however, the two paths diverged. While both objectors and non-objectors received lower contribution totals from Fortune 500 after adding control variables, Figure 4 illustrates that those who objected to the 2020 election results experienced a bigger decrease compared to non-objectors. Overall, the model predicts that non-objectors on key committees receive just under $700,000 whereas objectors on key committees receive less than $500,000 in contributions from Fortune 500 company PACs – a difference of around $200,000. Hypothesis 3 is supported by the available data – positions of power continue to yield benefits, albeit at a significantly reduced rate.

Table 4. Predictors of Fortune 500 PAC Contributions – Conditional on Objector Status and Membership on Key Committees

Note: * < 0.05 (two-tailed), ^ <0.10 (two-tailed). Models are fixed effects on members of Congress with robust standard errors. The dependent variable is the inflation-adjusted total PAC contributions in thousands of dollars.

Figure 4. Marginal effects of key committee membership.

Discussion and Conclusion

Corporate PACs faced a difficult choice after January 6. On the one hand, they rely on campaign contributions to maintain relationships with lawmakers and advance their interests. On the other hand, continuing to support those who challenged the election results risked backlash from employees, consumers, and investors who saw these actions as a threat to democratic norms. We argue that instead of making an all-or-nothing decision, many PACs adjusted their giving to balance these competing pressures. This tension between political access and public accountability shaped corporate responses in the wake of January 6 and continues to influence their role in the political system.

We find support for this balancing act in the aftermath of January 6. On average, Republicans who objected to the 2020 election results experienced a reduction in total contributions of $129,230 compared to non-objectors. This ‘objector penalty’ is similar in magnitude to the one faced by those who retired from Congress in 2022, and not accounted for by pre-existing contribution patterns. Although leaders and key committee members continue to receive benefits due to their influential roles, these benefits are diminished compared to their non-objecting counterparts in similar positions. Our results suggest that while companies strategically leverage access to influence policy, they also respond to stakeholder pressures by reallocating campaign contributions away from members of Congress who undermine democratic norms. It remains to be seen whether this shift will persist in future election cycles or if companies will eventually prioritize access over accountability, reverting to past patterns of campaign contributions in the wake of Donald Trump’s 2024 victory.

We believe that the evidence presented here offers valuable lessons beyond January 6. While Fortune 500 companies use campaign contributions to support their legislative goals, they are more than single-minded seekers of financial advantage using contributions in exchange for access. Large companies are organizations made up of people with preferences, and those preferences shape the strategies of the larger organization. Reducing campaign contributions to members of Congress is not merely symbolic but demonstrates big businesses’ desire to align with stakeholder preferences, even at the risk of losing access to those in power. Corporations’ use of financial power to penalize those who violate democratic rules is particularly notable considering their long-standing conservative leanings (Barari Reference Barari2024; Grumbach and Pierson Reference Grumbach and Pierson2019) and the aversion of many voters to sanction norm-violating politicians when facing a trade-off between democratic principles and their own policy goals (Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik2020).

Future studies should consider objectors’ overall fundraising efforts following January 6. Media reports suggest that objecting Republicans have been able to offset losses in PAC contributions by raising more money from small-dollar individual donors (Montellaro Reference Montellaro2021; Sonnenfeld and Tian Reference Sonnenfeld and Tian2022). Scholars should examine the extent to which these contribution patterns influenced candidates’ ability to pivot away from corporate America towards ideologically motivated activists and primary voters. Such a trend would fit the broader picture of severing ties between the GOP and its traditional allies in the business community. Many businesses see an increase in violations of democratic norms (Kalmoe and Mason Reference Kalmoe and Mason2022), predictions about higher levels of civil conflict in US politics (Walter Reference Walter2022), and the pursuit of ideologically extreme legislation by Republicans as threats. Notably, some on the right welcome this development for its potential to ‘liberate’ the party from corporate constraints on its ‘culture war’ (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2022). While the relationship between the Republican Party and big business is gradually evolving, a key takeaway from this study is corporate America’s ability to navigate its dual audiences – balancing the risk of losing access to power with the imperative to align with its stakeholders’ values.

Data availability statement

Replication Data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GBM3DR.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the discussants and participants at the 2023 Midwest Political Science Association conference in Chicago for their feedback. We also thank the anonymous reviewers whose suggestions considerably improved this manuscript. We are especially grateful for the comments and advice provided by Kris Miler, Craig Volden and Mike Hanmer throughout this project.

Financial support

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Competing interests

One of the authors was previously employed at the Public Affairs Council, which counts Fortune 500 companies among its clients.