The influence of corporations on public health policy, research and practice, and more specifically ‘corporate attempts to shape government policy in ways favorable to the firm’(Reference Hillman, Keim and Schuler1), known as ‘corporate political activity’ (CPA), has been well documented in other countries(Reference Mialon, Swinburn and Sacks2–Reference Mialon and da Silva Gomes7). CPA is divided into action-based strategies (called ‘instrumental strategies’) and argument-based strategies (called ‘discursive strategies’) (see online Supplementary Material 1)(Reference Ulucanlar, Fooks and Gilmore8). There is evidence that CPA of the food industry is one of the principal obstacles to the development of public health policies(9,Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Allender10) , such as restrictions on the marketing of unhealthy food products to children, increased soda taxation and nutrition front-of-pack labels (FOPL)(Reference Pomeranz, Zellers and Bare11–Reference Mialon, Julia and Hercberg14).

In Colombia, in 2018, civil society organisations promoted Bill 214 of 2018 (Proyecto de Ley or PL 214 de 2018) which covered three aspects: (i) the introduction of a new FOPL system with warning labels (WL) and for foods carrying those WL, (ii) the prohibition of marketing to children and (iii) the restriction of sales and marketing in schools(15). As of April 2020, WL have been adopted in Chile, Israel, Mexico, Peru and Uruguay(16–18). In Chile, early evidence suggests that the introduction of WL has led to a decrease in the purchase of unhealthy beverages(Reference Taillie, Reyes and Colchero19). The sales of unhealthy products could therefore be threatened by such law. In Colombia, this is the second attempt to introduce such a bill. In 2017, they proposed the bill PL019 de 2017, also known as the ‘Junk food law’ (‘Ley de la comida chatarra’)(20). The bill in its proposed format was not approved but modified into another bill (PL256 de 2018), which proposed to use the Guideline Daily Amounts (GDA), a FOPL system originally developed by a food industry in the UK and used voluntarily on some food product in Colombia(Reference Fernández and Suárez21). Evidence shows that the GDA system is less effective at helping consumers making healthier choices than WL(Reference Temple22,Reference Deliza, de Alcantara and Pereira23) . Thus, civil society organisations did not support that new bill. Furthermore, civil society noting that food industry actors lobbied policymakers, disseminated industry-friendly information in the media and promoted their existing self-regulatory efforts to counter mandatory regulation(Reference Fernández and Suárez21,Reference Sandoval Salazar24) . However, to date, no study has thoroughly documented the food industry’s attempts to influence the introduction of WL in Colombia. Our objective was to identify the CPA practices used by the food industry during the development of a new nutrition front-of-pack labelling system in Colombia.

Methods

The current study was part of a broader project on the CPA of the food industry in Latin America. We conducted a qualitative analysis, involving a document analysis along with interviews with key informants. All data were collected in Spanish between May and August 2019, and quotes were translated to English by the first author in the current manuscript. The aim of the document analysis was to identify the CPA recently used by the most prominent actors in the food industry (as described in the following sections). The aim of the interviews was to identify additional examples of the CPA in Colombia, including those that are not necessarily available in public data such as lobbying through direct contacts or the provision of financial incentives to policymakers. The interviewees provided context for the CPA in Colombia, shared specific CPA examples and discussed their perspectives regarding these practices.

For the purpose of the current research, ‘food industry’ means manufacturers of food and beverage products, wholesalers, retailers, distributors, food service providers, as well as producers of raw material. It also includes organisations acting on their behalf, overtly or covertly, including trade associations, public relations firms, ‘philanthropic’ organisations, research institutions and other individuals and groups. To report our research, we followed the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research(Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig25) (see online Supplementary Material 2).

Document analysis

For the document analysis, we followed the recommendations of International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support for identifying and monitoring the CPA of the food industry at the country level(Reference Mialon, Swinburn and Sacks2). These methods, including the framework used for our data analysis, have been applied in other countries(Reference Mialon, Swinburn and Wate4–Reference Mialon and da Silva Gomes7,Reference Tselengidis and Östergren13,Reference Mialon and Mialon26,Reference Jaichuen, Phulkerd and Certthkrikul27) and consist of a step-by-step analysis of the CPA of the most prominent industry actors in a given country.

Step 1: Identification of food industry actors

Based on a pilot study of the CPA of the food industry in Latin America and the Caribbean, conducted in 2018(Reference Mialon and da Silva Gomes7), and a discussion with local experts about their perspectives on who were the most influential actors in the country, we decided to include twenty food industry actors in our analysis. We included the twelve food manufacturers that are part of the International Food and Beverage Alliance, as these are amongst the most prominent food industry actors worldwide(28). These actors are Coca Cola, Danone/Alqueria, Ferrero, General Mills, Grupo Bimbo, Kellogg, Mars, McDonald’s, Mondelez, Nestlé, PepsiCo and Unilever. We also included four Colombian food manufacturers: Grupo Nutresa, Postobón, Colanta and Alpina. Grupo Éxito, a multinational company which owns supermarkets, was included in our sample, as well as two groups representing the food industry in Colombia, the Asociación Colombiana de Ciencia y Tecnología de Alimentos (Colombian Association of Science and Food Technology) and the Asociación Nacional de Empresarios de Colombia (the National Association of Businessmen of Colombia). Finally, we studied the activities of the branch of the International Life Science Institute in Colombia, ILSI Nor-Andino, a research foundation funded by the food industry(29).

Step 2: Selection of sources of information

Different sources of information were consulted for the current study and are presented in online Supplementary Material 3. These sources were identified through discussions with local experts and through a pilot study. These sources included the website(s) of the different industry actors, their Twitter accounts, as well as government material where it relates to nutrition, from the websites of the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Education, the Congress, the major political parties and the commissions in charge of elections. We collected additional information from the websites of major universities with a school/department of nutrition/dietetics/public health/ and/or exercise/physical activity, the websites of professionals associations, as well as information about major conferences in dietetics/nutrition/public health in Colombia. Among the industry actors, Mars, General Mills, Grupo Bimbo and Unilever had no national website or Twitter account.

Steps 3 and 4: Data collection and analysis

For each data source that was consulted online, we identified relevant information about the CPA in Colombia, navigating through the different web pages mentioned above. For the websites of the government, academia and civil society, we used the search engines on these websites, when available, and the names of the industry actors, to identify additional relevant information. Given our time constraints and number of actors selected, and based on the existing pilot study(Reference Mialon and da Silva Gomes7), we decided to include in our study data published between January and July 2019 (data were collected in July/August 2019). When there was no specific date on web pages, we collected the information available at the time of data collection. For annual reports and other events, we collected information for the most recent data available. When we identified information about the CPA of the food industry, the text was copied and pasted in an Excel document. In the document, we included additional information: name of the food industry actor, URL where the data were collected, date of data collection and notes/observations. Data collection and analysis were led by the first author. We collected and analysed the data in a deductive process, as recommended by International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support, using an existing framework for classifying the CPA of the food industry (see online Supplementary Material 1). The categories in this framework are not mutually exclusive, and some examples were included in multiple practices. The fourth author reviewed 100 % and the third author 10 % of the data for the document analysis. Disagreement was resolved after discussion between the authors, but not quantified.

Step 5: Reporting

From the results obtained about the CPA of the food industry in Colombia, in the current manuscript, we report about data that explicitly mentioned the development of a FOPL in Colombia. We present a narrative synthesis of our results and punctuate the following sections with illustrative examples of the CPA from our document analysis or interviews. All data from our document analysis are available in online Supplementary Material 4. When presenting these data, we use a code starting with the letter A followed by a number, from the online Supplementary Material 3. Information from our interviews is reported in quotes. To preserve the confidentiality and anonymity of our participants, we have removed all information that could identify our participants, only using generic terms to describe their professions and ‘she/her’ when referring to both male and female participants.

Interviews

The first author conducted fourteen semi-structured interviews with eighteen key informants in Colombia, including two group interviews. One person, from academia, accepted our invitation but could not be interviewed because she was travelling during the time of data collection. From the eighteen participants, one was a politician (legislative), one from the government (executive), one from academia, twelve from civil society and two from the media. We also interviewed a former food industry employee. We conducted interviews until data saturation was reached (i.e. when no new theme/CPA practices were identified by the interviewer). Sampling was purposive and based on the ability of participants to provide with information with regard to the CPA of the food industry in Colombia, as expressed in the media. We also used the snowball sampling technique, where participants were invited to identify additional potential interviewees through their networks.

Participation was voluntary. Participants were first contacted by email or through a phone call. During the day of the interview, an ethics consent form was signed, with information regarding: the study, their consent for the digital recording of the interview and for field notes to be taken, the possibility to revise the transcript before the submission of the current manuscript and the compromise of confidentiality and anonymity from the researchers. The interview guide is available in online Supplementary Material 5 (in Spanish). Interviews lasted 60 min on average and were conducted face to face (n 13) and on Skype (n 1). Interviews were conducted in Spanish (n 10), Spanish/English (n 3) and French (n 1). Interviews were transcribed verbatim by a contracted translator, with whom a confidentiality agreement was signed. After revising her transcript, one participant asked for most of the information contained in the document to be deleted, for fears of reprisals.

Data collection and analysis were led by the first author. We adopted the same approach to data analysis as our document analysis, using an existing framework for categorising the political practices of the food industry, in an iterative process. The last author reviewed 100 % and the second author 10 % of the data from the interviews. We used Microsoft Word and Excel to manage the data.

Results

In Colombia, we identified instances where food industry used its political practices during the development of new nutrition front-of-pack labels on food products. These strategies are presented in the sections below, using the different CPA categories to build a narrative synthesis of our findings.

Coalition management

A common corporate political practice of food industry actors is to build alliances with third parties in communities, the media and health organisations, amongst others. In March 2019, while the FOPL (PL 214 de 2018) was discussed in Congress, the food industry launched a public−private initiative, the ‘Alianza por la Nutrición Infantil’ (‘Alliance for Child Nutrition’) [A78, A82]. The objective of the Alliance was to have ‘the first generation in Colombia with zero chronic malnutrition by 2030’ [A82]. The first lady of Colombia participated in its launch in the capital city, Bogotá [A82]. Furthermore, a pact was signed with Colombia’s Attorney General and the Alliance partnered with the Ministry of Health, the Presidential Council for Children and Adolescents and the National Association of Neonatology, among others [A91–4, A101–2]. Industry actors stated that the partnership between the industry and the government ‘represent[s] the necessary articulation of the public and private sector to favour the rights of children’ [A82]. The event was later launched in other cities with the support of different city councils and in the presence of government officials or their partners [A89–90, A 95].

Information management

Food industry actors also influence the production and dissemination of evidence and information, in ways favourable to the industry. In parallel, corporations criticise and try to suppress evidence that does not fit the industry’s interests. In Colombia, during discussion in Congress and in their communication online on FOPL in 2019, food industry actors promoted their preferred FOPL system, the GDA, and discredited the proposed WL [A31, A39–40, A165–8]. Their main arguments were that the WL (i) were not aligned with international norms, citing here the Codex Alimentarius, a joint initiative of the WHO and the FAO in charge of establishing food standards, (ii) had no scientific basis and (iii) had no impact in the reduction of obesity in the country where they have been implemented (Chile was often mentioned) [A31, A40, A168, A174, interviews]. Here, the food industry used experts to defend its arguments without being transparent about these relationships. In our interviews, a public health advocate mentioned an academic, Susana Sokolowsky from Argentina, who was presented as an independent expert, intervened in Congress and in the media, but on occasions spoke on behalf of the industry:

She appeared both in the media and in the congress as an independent academic (…). However, exactly eight days later, in a [new] audience (…) in the Senate, they invited the companies (…). In this case Postobón said: “Postobón does not come” but they sent a video of their spokeswoman and it was [that same person]. (Public health advocate)

The International Life Science Institute, funded by the food industry and which has been criticised for its influence over public health policy and research at the international level(Reference Steele, Ruskin and Sarcevic30–32), has a branch for Colombia, Ecuador and Venezuela, called Nor-Andino (in reference to the Andes mountains). In 2019, ILSI Nor-Andino organised two workshops on FOPL: one in March, targeted at BSc students in nutrition and dietetics from the Faculty of Sciences of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana [A127] and one in August, during the annual congress of the Colombian Association of Dietetics and Nutrition [A117]. In the workshop in the university, the main speaker was presented as a member of ILSI, but he also worked at the same time for Nestlé [A127]. Among the three other scientists who were present that day, two were presented as members of ILSI but used to work for the food industry (Mondelez and Alpina) [A127]. We found no detail about the content of these presentations. One of our interviewees described another event in the Faculty of Nutrition of the National University of Colombia, where ‘students who were going to graduate (…) got an email, telling them that a food company was going to invite them to a dinner for their graduation and also wanted to [present] a FOPL workshop’ (public health advocate).

Direct involvement and influence in policy

A well-known political practice of corporations is to directly influence policy, including through their lobbying of politicians or their donations to political parties and policymakers. We observed the use of such practices in Colombia, in the case of the development of the FOPL policy. The lobby of the food industry against the WL was discussed by our participants, explaining ‘[In the discussion on FOPL], I had never seen so many lobbyists. There were more than 60 people between the lobby companies and the food industry outside the Congress elliptical room, looking for allies for the bill to sink, or the bill to lose its essence’ (politician).

Our interviewees also explained that some government agencies, such as the Ministry of Commerce, the Ministry of Agriculture and the Instituto Nacional de Vigilancia de Medicamentos y Alimentos or National Institute for Food and Drug Surveillance, also lobbied alongside the food industry, including through the use of the revolving door, where former industry members eventually work in the government (or the opposite). A public health advocate recollected how the industry had ‘co-opted the Ministry of Health to these agendas’ by bringing in the discussions to the Ministry of Commerce to defend the positions of Codex and present the negative impacts WL would have on foreign trade. The interviewee also noticed that Instituto Nacional de Vigilancia de Medicamentos y Alimentos or National Institute for Food and Drug Surveillance, when discussing labelling, was using ‘exactly the same discourse as the industry’. In May 2019, the Codex Alimentarius Commission organised a discussion on FOPL in Canada. In the meeting, Colombia had a delegation of five individuals, none of them working for the Ministry of Health, despite the impacts FOPL have on population health: three individuals were from ANDI, one from the Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism and one from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs [A14]. The media also reported that one of the former directors of ANDI, and now Presidential advisor, as well as other individuals from Postobón, lobbied Senators during the discussion on FOPL [A142–3]. The Ministry of Defence, which used to work for the National Federation of Merchants (Federación Nacional de Comerciantes), therefore representing corporations, was also lobbying on the industry side against the WL (interview, member of government). The Minister of Health, as of December 2019, was a former director of the Santa Fé Foundation, which receives funding from the Grupo Ardila Lulle, owner of Postobón. Some interviewees suggested that this could have been the reason why the Minister supports the interactions between the government and the industry.

The current Minister of Health, (…) says that they are a much more open government, that the industry must be heard. (…) [He] openly says he is talking to the industry. (Public health advocate)

One participant noted that the industry felt ‘victimised’ during the discussion and that ‘Congressmen (….) said they did not support the bullying that civil society was doing to [the industry]’ (public health advocate).

In their efforts to show support for the government, food industry actors welcomed the idea of using a FOPL system on food products [A29, A33, A40, A218]. The Asociación Nacional de Empresarios de Colombia and Postobón welcomed the openness of the government for participation of the food industry in the discussion and stressed the fact that they were voluntarily using the GDA system since 2016 [A18, A41, A143, A153, A169, A256, A258, A273], thus advocating for self-regulation rather than the introduction of a mandatory FOPL chosen in a democratic process.

Legal strategies

Finally, food industry actors and their allies in the government threatened to use legal actions during the public hearings for the FOPL policy in 2019, a known political practice employed by corporations when faced with the possible adoption of public health policies that would limit the sales of their commodities. This was a practice detailed by our interviewees:

In the hearing that was held in the Congress of the Republic, the speaker from academia (…) clearly showed that if Colombia continued (…) promoting these initiatives, they could present [the case] to international trials, particularly arbitration tribunals, the WTO [World Trade Organization]. (Public health advocate)

Discursive strategies

To support their instrumental strategies, food industry actors made use of a number of argument-based, discursive strategies when opposing the WL system in Colombia. Several participants noted that the food industry issued common economic arguments, describing the negative effects that WL would have on trade in Latin America:

The issue of legal instability, was as a novelty, and in the case of labelling, this year, the issue of its effects on foreign trade - so much so that at the last audience [in mid-2019], they brought the Colombian-Venezuelan Chamber of Commerce, the Ministry of Commerce, ALAIAB [Alianza Latinoamericana de Asociaciones de la Industria de Alimentos y Bebidas, Latin American Alliance of Food and Beverage Industry Associations]. (Public health advocate)

Here is the other argument, which is the strongest they have used for labelling, which is affecting international trade … and generates legal instability. (Public health advocate)

In the FOPL discussion in Colombia, the industry pointed to the consumer as responsible for its own choices and the industry as a necessary ally to help consumers make these choices [A34, A36, A218]. While the industry said it was supporting the introduction of a FOPL system, one participant described how the food industry tried to delay its development:

This issue of cost of compliance, for example, is widely used to avoid changes in the labelling, yes. For the cost of the packing material and for the time it would take to change everything. It is one of the most powerful arguments to delay the application of regulation (…) it is a mechanism to save time. (Former food industry employee)

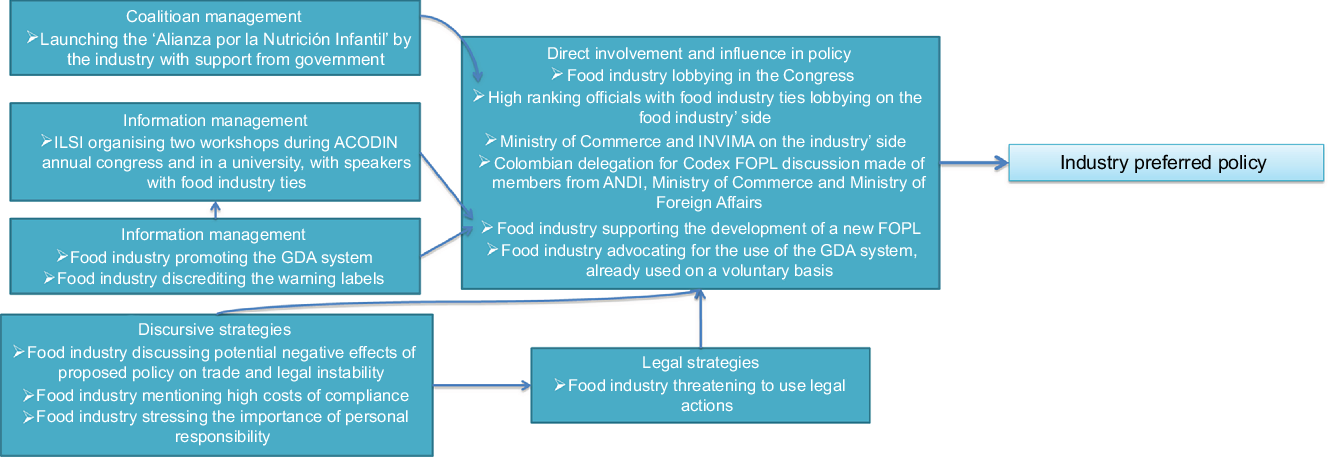

In Fig. 1, we have constructed a model to illustrate how these different strategies could be combined and may have influenced the FOPL policy in Colombia.

Fig. 1 Illustration of how these different corporate political activity (CPA) strategies were combined and may have influenced the front-of-pack labels (FOPL) policy in Colombia

During the year 2019, the food industry was directly involved and influencing the policy process in Colombia, through lobbying in the Congress and its participation in the Codex meeting on FOPL, in May, and the promotion of its existing voluntary efforts. Other strategies may also have had an indirect influence on the policy process. This is the case of the launch of the Alliance in nutrition in March 2019 and the presentations made by ILSI in March and August the same year, given their timing, during discussions in the Congress, and through the relationships then established with government decision makers and public health professionals. The information used by food industry actors against the WL and for the GDA system was feeding these discussions as well. Finally, the arguments used by the industry on the potential negative aspects of the proposed policy, and its threats of litigation, may have also influenced the development of the FOPL discussion.

Discussion

Our study confirms the testimonies of civil society organisations that food industry actors lobbied in the Congress and pushed for their agenda in the media, in their attempts to prevent the adoption of WL in Colombia(Reference Fernández and Suárez21,Reference Sandoval Salazar24) . But we found that the industry also used a much broader range of CPA strategies during the FOPL policy-making process. Specifically, food industry actors developed partnerships with third parties, including those in the government, and launched a public−private alliance in the presence of members of the government in different parts of the country. These actions may have helped the industry build relationships with authorities and show that they could be part of the solution(Reference Marks33). However, partnering with industry actors risks compromising the integrity and credibility of government decision-makers and their institutions(Reference Marks33). The food industry used experts to promote its preferred FOPL and discredit the proposed WL, including through events organised by ILSI. The industry used different arguments to criticise the proposed WL but did not provide peer-reviewed scientific evidence to sustain these claims. Moreover, it is important to note that individuals make healthy choices if they evolve in a healthy environment. The purpose of the FOPL was to protect and promote these healthy environments, so this was not in contradiction with individual choices. We also noted that there was an intense lobbying in the Congress and that food industry actors were part of the Colombian delegation in the Codex discussion on FOPL.

These results add evidence to the existing literature on the CPA of the food industry and particularly on the efforts of industry actors to negatively influence the development of a new FOPL(Reference Mialon, Swinburn and Sacks2,Reference Mialon, Julia and Hercberg14,17,Reference Ares, Bove and Díaz34) . In Canada, Chile and France, the food industry delayed the development and implementation of a FOPL, including WL, created divisions in the public health community and among policymakers by lobbying for the adoption of industry-friendly FOPL, deflected the attention from the FOPL discussion to issues related to commerce and trade and denied evidence that new FOPL systems proposed by governments were effective(17,Reference Corvalán, Reyes and Garmendia35) . In France, for example, the food industry lobbied for the collection and analysis of additional evidence, promoted an alternate FOPL model, shifted its lobbying efforts on the national authorities to the European Union and built alliances with the media(Reference Mialon, Julia and Hercberg14). Unlike in other countries, in Colombia, food industry actors are very close to the governments, with some members of large trade associations now being in decision-making positions in the public sector. This means that the commercial interests of the food industry are now represented in the government, in what is called ‘regulatory capture’(Reference Miller and Harkins36).

In addition, our results show that the government endorses large nutrition initiatives from the food industry. Codex is also a platform through which the industry gains access to decision-making, which could be at the detriment of public health. In particular, the industry’s current involvement with Codex negotiations could help establish weak and corporate-friendly Codex nutrition labelling standards that pre-empt countries from adopting more effective FOPL with WL(Reference Crosbie, Hatefi and Schmidt37), and in some cases force countries through new trade agreements(Reference Labonté, Crosbie and Gleeson38). This merits further investigations. Our findings are also similar to the CPA strategies used by the tobacco industry during the development of tobacco plain-packaging legislations, which could be considered as the closest equivalent to the WL for foods(Reference Hatchard, Fooks and Gilmore39,Reference Crosbie and Thomson40) . In response, governments should adopt a ‘whole-of-government’ and ‘health-in-all policies’ approach that incorporates health norms and practices with other parts of government to minimise both inter-sectoral conflicts and industry interference(Reference Crosbie, Thomson and Freeman41).

A limitation of our study is that we have only analysed some of the largest actors in the food industry, but other actors might also be influential. Moreover, our period of analysis only covers a fraction of the discussion on the FOPL policy, and more work is needed to better understand how the industry influenced its initiation, early development, and how it, perhaps, will influence the implementation of the WL in the near future. We have included data from the public domain and data from interviews, and most individuals willing to discuss the CPA of the food industry where those from civil society. It was particularly difficult to get access to members of the industry without compromising our safety and independence, as the food industry has a vested interest in the discussion on the adoption of new nutrition front-of-pack labels, although we managed to get access to a former industry staff member. In addition, studying the effects that these different CPA practices had on the policy process was beyond the scope of our project. It is likely that we would never have had access to the true intentions behind the use of such practices, as these involve complex psychological mechanisms(Reference Marks33). But the food industry would not invest time and money if these were not useful. Further work on the CPA could be based on additional sources of information and include ethnographic and anthropological studies, for example, not only in the Congress but also in communities and local branches of the government where the industry is interacting with government officials and communities. The International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support protocol to monitor the CPA of the food industry, used in the current study, does not include public data from the Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism or Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In addition, we did not identify informants from these Ministries willing to discuss about the CPA in Colombia. These are powerful actors in governments that, without necessarily being influenced by the industry, could oppose public health policies. These internal forces need to be addressed, particularly in neoliberal economies, where economic development might be prioritised over public health goals and the protection of natural resources and vulnerable populations. Finally, this was not a study of the FOPL policy per se and of the dynamics between different actors involved in that process, but this could be the subject of future research projects.

The food industry was opposed to previous efforts to introduce a new FOPL in the country (PL019 de 2017). It was the strongest opponent to the bill PL214 for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases in Colombia. Despite the use of such political practices, in February 2020, the President of Colombia declared that WL would be mandatorily adopted in the country on all packaged foods from the end of 2022(42). There is still an urgent need to learn and condemn the practices of corporations that would prevent the implementation of internationally recommended measures, in Colombia and abroad, FOPL and WL being only of them(43,Reference Popkin, Willett and Monteiro44) . There is a need to better protect public health from undue influence from the food industry, including through the implementation of lobbying regulation and conflicts of interest policies, for example(45).

Conclusion

We found evidence, both in the public domain and through our interviews, that food industry actors in Colombia used a broad range of political practices during the development of new nutrition front-of-pack labels. These included the development of an Alliance with third parties from the public sector right when the Congress was discussing the adoption of new labels and intense lobbying against the WL in the Congress itself. Moreover, the food industry used scientific experts to promote its preferred FOPL and discredit the proposed WL, in the Congress and other events, some of those being supported by ILSI. These results could be shared among civil society organisations, academics, policymakers and, more importantly, the public, as they would benefit from the adoption of an evidence-based nutrition labelling policy.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge Cora-Lee Leblanc, from the University of Moncton, Canada, for her contributions in the early stages of the current study. The authors would also like to thank their participants for their involvement in the current study. Financial support: M.M. received a Fellowship from the São Paulo Research Foundation, Brazil (grant no. 2017/24744-0). M.M. obtained seed funding from the Faculty of Health Sciences at the American University of Beirut, as part of a grant funded by the International Development Research Centre. This funding supported her fieldwork in Colombia and Chile in 2019. F.B.S. received a fellowship from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, Brazil (grant no. 309514/2018-5). The funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of the current article. The authors are solely responsible for the opinions, hypotheses and conclusions or recommendations expressed in the current publication. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: M.M. led the study design, data collection, analysis and writing of the manuscript. F.B.S. contributed to the study design. D.A.G.C., G.C. and E.M.P.T. contributed to the study design, data collection and analysis. E.C. contributed to data analysis. All authors contributed to the manuscript writing and read and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study, which was part of a broader project on the food industry in Latin America, was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by the ethics committee of the School of Public Health, University of Sao Paulo, Brazil (project no. 07944118.7.0000.5421). An ethics informed consent form was signed by the participants before they took part in the study.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020002268