Introduction

During the perinatal period (during pregnancy and the year after) parents are at an increased risk of developing a mental health problem (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Knapp and Parsonage2016) including perinatal obsessive-compulsive disorder (PNOCD; Forray et al., Reference Forray, Focseneanu, Pittman, McDougle and Epperson2010). Perinatal mental health problems result in substantial cost to health and social care budgets, estimated to be between £6.6 and £8.1 billion across the United Kingdom (UK) annually when accounting for subsequent childhood issues (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Knapp and Parsonage2016; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Tinelli and Knapp2022; Howard and Khalifeh, Reference Howard and Khalifeh2020). Therefore, it is important to ensure timely access to support for perinatal mental health problems. It is estimated that between 2 and 24% of mothers in the perinatal period experience PNOCD (Hudepohl et al., Reference Hudepohl, MacLean and Osborne2022). An even larger number experience subthreshold symptoms, with 95% of women reporting intrusive thoughts of accidental harm at 12 weeks post-partum (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Schwartz and Moore2003a; Fairbrother et al., Reference Fairbrother, Janssen, Antony, Tucker and Young2016; Fairbrother and Woody, Reference Fairbrother and Woody2008; Miller and O’Hara, Reference Miller and O’Hara2020). Intrusive thoughts are normal during the perinatal period. However, when they cause impairment due to distress, they can become PNOCD (Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Bavetta and Degiorgio2019). In perinatal populations, obsessions can involve unwanted thoughts of harm coming to the infant, including thoughts of harming the baby oneself or harm coming to the baby accidentally (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Schwartz, Moore and Luenzmann2003b). PNOCD symptoms can have a significant impact on both the parent and the child, with diagnosed parents reporting a mean time of 9.6 hours per day being troubled by symptoms (Challacombe et al., Reference Challacombe, Salkovskis, Woolgar, Wilkinson, Read and Acheson2016).

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is the primary treatment recommended by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (NICE, 2005) for OCD. Its effectiveness is well-established for OCD in both general adult and perinatal parent populations (Challacombe and Salkovskis, Reference Challacombe and Salkovskis2011; Olatunji et al., Reference Olatunji, Davis, Powers and Smits2013). In the UK, CBT for OCD is recommended over and above medication (NICE, 2005). In perinatal populations, CBT has been found to be significantly better than anti-depressant medication alone at improving symptoms and parenting behaviours (Marchesi et al., Reference Marchesi, Ossola, Amerio, Daniel, Tonna and De Panfilis2016).

Equity of access is a priority for the UK’s National Health Service (NHS England, Reference England2013). Timely treatment access reduces significant costs to society and the healthcare system (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Knapp and Parsonage2016; Howard and Khalifeh, Reference Howard and Khalifeh2020). The 2019 NHS long-term plan aimed to get 24,000 further women to specialist perinatal mental healthcare by 2023/4, directing additional funds accordingly (Kulakiewicz et al., Reference Kulakiewicz, Parkin and Baker2022). Furthermore, general practitioners (family physicians, GPs) are contractually obliged to have a consultation with new mothers about their physical and mental health at six to eight weeks postnatally (Kulakiewicz et al., Reference Kulakiewicz, Parkin and Baker2022). NICE guidance also states that during every appointment with perinatal women, healthcare professionals should ask about how they are feeling (NICE, 2014). Research has shown that primary care services tend to focus only on detecting depression, while specialist perinatal mental health services may be restricted to patients with serious mental illnesses (Kulakiewicz et al., Reference Kulakiewicz, Parkin and Baker2022). Access problems have increased post-pandemic; however, while services are rapidly adapting to meet the needs of those with more complex and severe perinatal mental health problems, they are yet to offer quality care for those experiencing common mental health problems (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Tinelli and Knapp2022).

Research suggests that one barrier is a lack of healthcare professional knowledge of PNOCD, leading to under- and misdiagnosis (Burton et al., Reference Burton, Pickenhan, Carson, Salkovskis and Alderdice2022; Sharma and Mazmanian, Reference Sharma and Mazmanian2021). Previous research has found that over 70% of OCD patients with presenting symptoms were overlooked by consultant psychiatrists (Wahl et al., Reference Wahl, Kordon, Kuelz, Voderholzer, Hohagen and Zurowski2010). Misdiagnosis of PNOCD as perinatal depression has been cited as being due to lack of awareness of PNOCD (Challacombe and Wroe, Reference Challacombe and Wroe2013) and as PNOCD can present as anxiety and avoidant behaviours which overlap those seen within anxiety and depression (Sharma and Sommerdyk, Reference Sharma and Sommerdyk2015). A study looking at perinatal healthcare professionals’ recognition of PNOCD found that when presented with vignettes of PNOCD, 30.9% recognised the symptoms as PNOCD, 30.8% recognised symptoms as psychosis, 16.9% as depression and 24.6% were not sure what the symptoms were (Mulcahy et al., 2020). This misdiagnosis may result in inappropriate treatment or medication doses which can be ineffective or potentially cause harm; research found that the majority of perinatal health practitioners surveyed endorsed management strategies which could aggravate PNOCD symptoms (Mulcahy et al., 2020). Similarly, a questionnaire study found when psychiatrists were presented with vignettes of filicide obsessions, 60% included involuntary admission and 68% included reporting to child welfare authorities as their preferred management strategies, highlighting the need for improved PNOCD awareness (Booth et al., Reference Booth, Friedman, Curry, Ward and Stewart2014). Misrecognition of PNOCD and intrusive thoughts can result in clinicians making inappropriate referrals to treatments including admittance to in-patient units, meaning the parent could be seen as high-risk to the child and can result in social care services enforcing restricted contact with their child (Challacombe and Wroe, Reference Challacombe and Wroe2013). PNOCD often results in obsessions around harm coming to one’s child, and inappropriate safeguarding referrals can exacerbate this distress further, harming the parent–baby relationship (Challacombe and Wroe, Reference Challacombe and Wroe2013; Sharma and Sommerdyk, Reference Sharma and Sommerdyk2015). Even healthcare professionals who report feeling confident and skilled about supporting those with perinatal mental health issues have been found to lack knowledge and skills to address the full spectrum of mental health issues including PNOCD (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Downes, Carroll, Gill and Monahan2018). Thus, improvements are needed in how PNOCD is recognised and diagnosed (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Meltzer-Brody, Leserman, Killenberg, Rinaldi, Mahaffey and Pedersen2010; Mulcahy, Reference Mulcahy2021; Sharma and Mazmanian, Reference Sharma and Mazmanian2021).

Barriers to appropriate care exist not just at the level of recognition by HCPs. Often parents experience personal barriers including feeling stigma, shame or guilt around symptoms impacting their help-seeking behaviour (Burton et al., Reference Burton, Pickenhan, Carson, Salkovskis and Alderdice2022; Sharma and Mazmanian, Reference Sharma and Mazmanian2021). There are numerous barriers to accessing support and treatment for PNOCD. Identifying the most influential and modifiable barriers is crucial, as addressing these may significantly improve parents’ access to the support they need.

There is limited research on healthcare professionals’ perspectives on accessing support for PNOCD. A recent Delphi study reports on healthcare professionals’ recommendations for improving assessment and treatment for PNOCD (Mulcahy et al., Reference Mulcahy, Long, Morrow, Galbally, Rees and Anderson2023). However, it was conducted across Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom; thus, it is not specific to the NHS. Furthermore, this research presents 102 endorsed statements but does not prioritise or order recommendations. There is a need for research to identify which barriers healthcare professionals see as the most important or amenable to change, and to situate these barriers within the context of the English NHS. Therefore, this study aimed to prioritise a list of barriers to accessing evidence-based psychological therapies (EBPT) for PNOCD, in terms of importance and amenability to change, from the perspective of healthcare professionals.

Amenability to change and importance are included in order to allow identification of barriers which, when addressed, would have a high likelihood of increasing access to support.

Method

Design

An observational cross-sectional mixed-methods survey was used. This paper presents the quantitative results. The survey was designed by the research team, including a clinical psychologist, and a general practitioner (GP) was consulted.

Participants

Professionals were recruited through 24 NHS Trusts in England. Participants were recruited by study advertisements being shared with potentially relevant professions through emails, staff networks, and social media promotion. The recruitment poster and a study summary explained to participants that The Open Door Project aimed to explore barriers to accessing support for PNOCD and invite professionals’ opinions to develop practice recommendations. Inclusion criteria were that professionals held a clinical role within the NHS and interacted with perinatal populations, including those from non-perinatal specialist services. Healthcare professionals from different occupations, healthcare settings (including perinatal specialist and general adult population services) and regions of England were recruited. This was to include a range of perspectives of those who come into contact with perinatal populations, as PNOCD presentations, disclosures or help-seeking could occur when interacting with any of these professionals. For example, it is important to understand primary care staff’s perspectives as they can be gatekeepers to support. No exclusions were made for those who had no contact with individuals who had experience with PNOCD; however, these individuals went on to answer different questions, not reported here.

Survey and study measures

A survey was created for this study. Participants self-reported demographic information including gender, ethnicity, and occupation. They also reported work-related information such as whether they worked in a perinatal service, and their years in their role. Participants were also asked about their interactions with people experiencing PNOCD and OCD. Participants were then asked about their confidence in treating, diagnosing and supporting people with PNOCD. Participants were asked to report any PNOCD-relevant training.

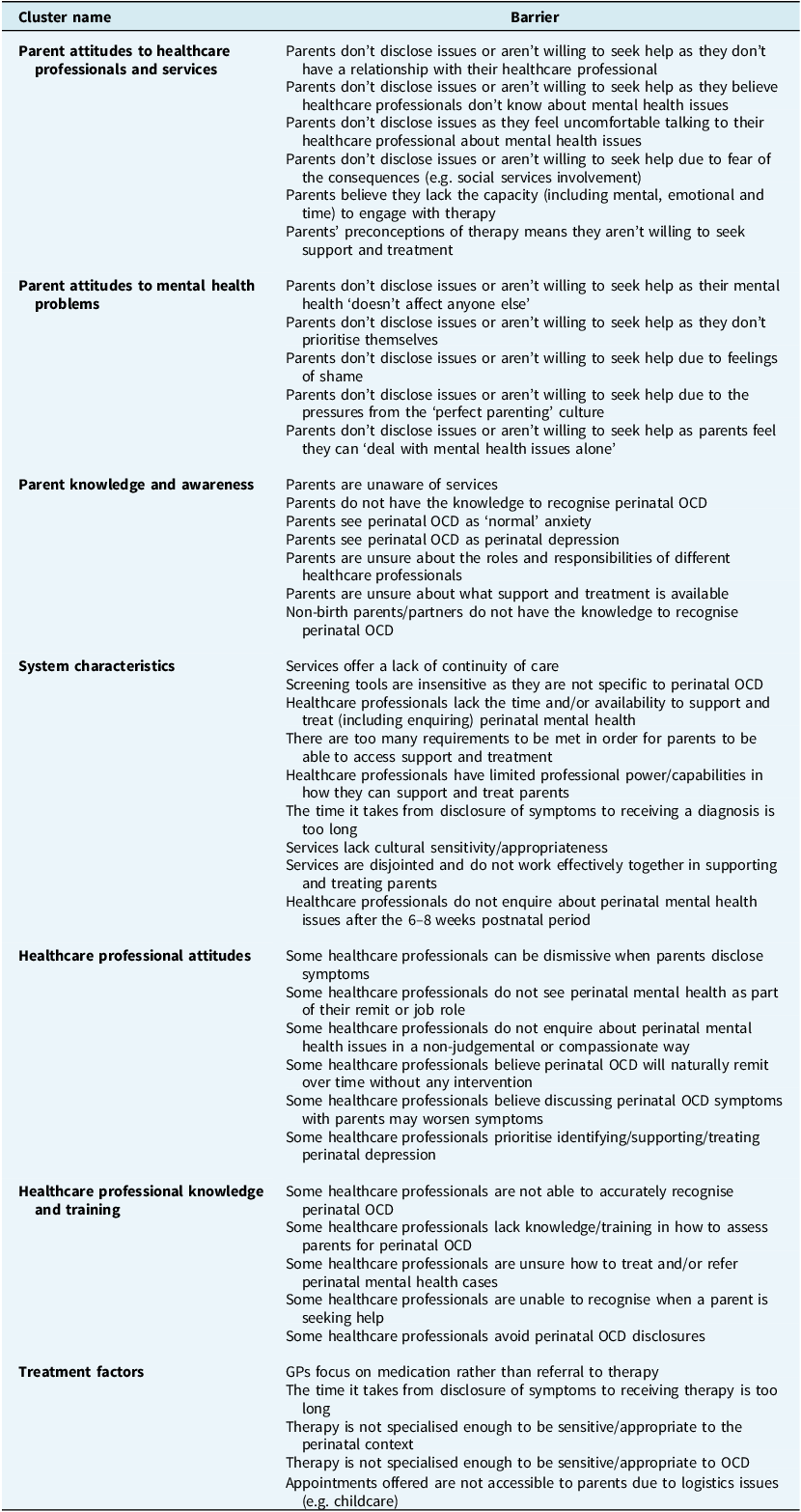

Participants with experience with PNOCD were directed to a list of 47 barriers which was developed using findings from previous interview research and searches of the wider PNOCD literature on parents’ access to support such as Mulcahy et al. (Reference Mulcahy, Long, Morrow, Galbally, Rees and Anderson2023). The barriers were grouped conceptually by the research team into seven clusters based on their content. The full list of barriers can be found in Table 1. Participants were presented with each of the seven clusters and asked to rank the barriers within each cluster in order of importance and then rank them again with respect to amenability to change. Participants were then presented with the seven cluster names and were asked to rank them in order of importance and how amenable to change they were. Rankings were assigned numerical values, where 1 was the most important/amendable to change, and between 5 and 7 were the least important/amenable to change, depending on the number of items.

Table 1. Barriers and clusters to accessing evidence-based psychological therapy for perinatal obsessive-compulsive disorder presented in the survey

Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 28). Descriptive characteristics were calculated using means, percentages, and range. For each barrier and each cluster, the median rank value was calculated across the responses. Friedman (non-parametric ANOVA) tests were used to determine the nature and significance of this differences in rank values. All pairwise comparisons were produced, with Bonferroni corrections applied for multiple testing, to identify whether each average rank value was significantly significant than that of another barriers/cluster. Kendall’s W was also calculated to assess the effect size of the difference in mean preference rankings with 0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 approximating to a small, moderate and large effect, respectively (Walker, Reference Walker2003). The same statistics for subgroups with over 20 participants were also calculated to investigate if subgroup professions perspectives differed from the overall perspective, along with Mann–Whitney tests to identify associations between subgroups training and confidence in treating and identifying PNOCD.

Results

Participant characteristics

In total, 486 professionals consented to the survey; 68 of these did not rank the barriers as they did not have experience working with someone experiencing PNOCD and 218 did not complete the ranking task, likely due to attrition. Therefore, 203 professionals completed the full questionnaire and thus were included for analysis. Participants completing the rankings were predominantly White and female. Participants ranged in occupation, including 19 Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners (9%), 14 psychiatrists (7%), 22 CBT therapists (11%), 23 practitioner psychologists (11%), 16 midwives (8%), 16 health visitors (8%) and 53 nurses (26%). Overall, 125 participants worked in a perinatal service (62%). On average, participants had worked in the NHS for 7.32 years (SD=5.38). Participant characteristics and details of participants’ interactions with patients with PNOCD are presented in full in the Supplementary material. Overall, participants predominantly saw themselves as supporting patients with PNOCD, interacted with them at least once a month (n=97, 48%), and had worked with an average of 15.91 patients with PNOCD.

Only professionals who completed the full survey were included in analysis. A chi-square test was carried out to assess if there was a significant difference between those included in analysis and those not. There were no significant differences in this population according to gender, ethnicity and years of experience in their professions. However, there were significant differences in terms of profession (χ2 (18, n=545)=41.06, p=0.01); those who worked in perinatal specific services (χ² (2, n=545)=7.99, p=0.018) with a higher proportion of survey completer working in perinatal services (62%) than survey non-completers (53%); how often professionals worked with people with PNOCD (χ² (8, n=545)=90.19, p<0.01) and how many people with PNOCD they had worked with (χ² (42, n=545)=67.92, p=0.007) with survey completers having worked with a mean of 17 people (SD=22.1) with PNOCD, compared with a mean of 13 (SD=27.4) for survey non-completers.

Participants were asked about their confidence and training in relation to PNOCD. Overall, 62% of participants (n=126) had not received training for treating PNOCD, and 55% (n=112) had not received training for identifying PNOCD. The results from the Mann–Whitney tests can be found in the Supplementary material. These have also been broken down into professional subgroups for analysis. It appears when participants had received training on a treating or identifying PNOCD, they felt more confident than when they had not. This trend appeared within each of the subgroups and each of the tests are significant.

Healthcare professionals’ prioritisation of barrier cluster names

Full results of preferences can be found in Table 2. The Friedman’s test across the cluster names was highly significant for both importance, χ2(6)=220.101, p<0.001 and amenability to change, χ2(6)=200.618, p<0.001. This means that there is a statistically significant difference between the mean ranks of the cluster names. Analysis across the cluster names found small to moderate effect sizes for differences in ranking of both importance and amenability to change (Kendall’s W=0.18 and 0.26 respectively).

Table 2. Healthcare professionals ranked elements of barriers to accessing evidence based psychological therapy for perinatal obsessive-compulsive disorder

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The pairwise comparisons show that overall, healthcare professionals rated ‘healthcare professional knowledge and training’ as the cluster of barriers that was most important and most amenable to change (ranked 2.59 and 2.09, respectively, on a ranking scale of 1 to 7). This was followed by parents’ knowledge and awareness (ranked 3.35 and 3.16, respectively), parents’ attitudes to healthcare professionals and services (ranked 3.80 and 3.77, respectively), and parents’ attitudes to mental health problems (ranked 3.69 and 4.29, respectively). These were not found to be significantly different from one another in importance, i.e. they each reflect the second most important clusters of barriers as ranked by participants. Parents’ knowledge and awareness and parent attitudes to professionals and services were not significantly different in amenability to change, i.e. both reflect clusters of barriers considered the second most amenable to change. System characteristics, professionals’ attitudes, and treatment factors were considered the least important and amenable to change (see Supplementary material). The pairwise comparisons for the clusters can be found in Figs 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Pairwise comparisons among all clusters in terms of importance. Dashed lines, p>0.05; dotted line, p<0.05; double lines; p<0.01, single lines; p<0.001; bold items rated as most important/amenable to change, 1=most important/amenable to change, highest number=least important/amenable to change.

Figure 2. Pairwise comparisons among all clusters in terms of amenability to change. Dashed lines, p>0.05; dotted line, p<0.05; double lines; p<0.01, single lines; p<0.001; bold items rated as most important/amenable to change, 1=most important/amenable to change, highest number=least important/amenable to change.

Healthcare professionals’ prioritisation of barriers within clusters

All Friedman’s tests within each cluster were highly significant (p<0.001), meaning that there was a statistically significant difference between the mean ranks of the barriers within each cluster. The Kendall’s W were between 0.05 to 0.46, suggesting small to moderate effect sizes, therefore the barriers’ sum ranks were small to moderately different from one another. Findings of all the pairwise comparisons denoting the hierarchy of prioritisation can be found in the Supplementary material. These figures indicate how each barrier differs in prioritisation ranking compared with all other barriers in that cluster. Often the barriers which are seen as the most important, are also seen as the most amenable to change. The within-cluster results for the four clusters ranked as most important are described here, with results for the other clusters presented in the Supplementary material.

Prioritisation within the cluster ‘Professionals’ knowledge and training’

The Friedman test for the barriers within the cluster ‘Professionals’ knowledge and training’ was statistically significant for both importance, χ2(4)=328.51, p<0.001, and amenability to change, χ2(4)=236.78, p<0.001. Pairwise comparisons identified that two barriers were seen as the most important and amenable to change: ‘some healthcare professionals lack knowledge/training in how to assess parents for perinatal OCD’ and ‘some healthcare professionals are not able to accurately recognise perinatal OCD’. These pairwise comparisons can be seen in the Supplementary material. ‘Parents’ knowledge and awareness’ was ranked as the second most important cluster of barriers and that second most amenable to change. The two barriers seen as significantly the most important were ‘Parents are unaware of services’ and ‘Parents do not have the knowledge to recognise PNOCD’. The barrier seen as significantly the most amenable to change was ‘Parents are unaware of services’ followed by ‘Parents do not have the knowledge to recognise PNOCD’.

Prioritisation within the cluster ‘Parents’ attitudes to mental health problems’

The Friedman test for the barriers within the cluster ‘Parents’ attitudes to mental health problems’ was statistically significant for both importance, χ2(4)=273.34, p<0.001, and amenability to change, χ2(4)=28.75, p<0.001. This cluster was ranked as the third most important and fourth most amenable to change. Pairwise comparisons identified that the barrier rated as significantly the most important in this cluster was ‘Parents don’t disclose issues or aren’t willing to seek help due to feelings of shame’. This was also seen significantly as the most amenable to change, along with ‘Parents don’t disclose issues or aren’t willing to seek help as their mental health doesn’t affect anyone else’.

Prioritisation within the cluster ‘Parent attitudes to health professionals and services’

The Friedman test for the barriers within the cluster ‘Parent attitudes to healthcare professionals and services’ was statistically significant for both importance, χ2(5)=405.259, p<0.001, and amenability to change, χ2(5)=136.792, p<0.001. This cluster rated as the fourth most important and third most amenable to change. Pairwise comparisons identified that the barrier rated as significantly the most important within this was ‘Parents don’t disclose issues or aren’t willing to seek help due to fear of the consequences (e.g. social services involvement)’. Within this cluster, four barriers were ranked as significantly the most amenable to change: ‘Parents don’t disclose issues or aren’t willing to seek help as they don’t have a relationship with their healthcare professional’; ‘Parents don’t disclose issues as they feel uncomfortable talking to their healthcare professional about mental health issues’; ‘Parents don’t disclose issues or aren’t willing to seek help as they believe healthcare professionals don’t know about mental health issues’; ‘Parents don’t disclose issues or aren’t willing to seek help due to fear of the consequences (e.g. social services involvement)’.

Discussion

This is the first known study investigating how healthcare professionals prioritise barriers to accessing therapy for PNOCD, in terms of importance and amenability to change. The significance of all Friedman’s tests demonstrates that some clusters of barriers, and specific barriers within each conceptual cluster, are considered more important and more amenable to change than others.

The study highlights that professionals view professional training and knowledge of PNOCD as the most important barrier on which to focus, with respect to improving access to EBPT for people experiencing PNOCD, and as the most amenable to change. Within this cluster, professionals ranked professionals lacking knowledge and training on assessing parents for PNOCD, and their ability to accurately recognise PNOCD, as significantly the most important. This can be linked to access theories such as Levesque and colleagues (Reference Levesque, Harris and Russell2013), where once engaging with services, their appropriateness is an important factor which is defined as the technical/interpersonal quality and adequacy of services. Our findings align with previous research that suggests that professionals see assessment of PNOCD as a barrier to accessing support (Mulcahy et al., Reference Mulcahy, Long, Morrow, Galbally, Rees and Anderson2023). Professional lack of recognition of OCD has also previously been identified as creating barriers to accessing support and thus calls for increased OCD training for professionals (Vuong et al., Reference Vuong, Gellatly, Lovell and Bee2016). Training on perinatal mental health for professionals such as midwives has been found to be perceived as inadequate (Noonan et al., Reference Noonan, Doody, Jomeen and Galvin2017). The implementation of training on recognising mental health conditions has been found to improve professional knowledge, attitudes, skills, confidence clinical practice and patient outcomes (Caulfield et al., Reference Caulfield, Vatansever, Lambert and Van Bortel2019). Previous interventions have been successful in changing primary care professionals’ attitudes and practices towards mental health (MacCarthy et al., Reference MacCarthy, Weinerman, Kallstrom, Kadlec, Hollander and Patten2013). Our findings also suggest that confidence increases if someone has engaged in training. It is notable, however, that 55% of our respondents had not received training for identifying PNOCD themselves. However, 52% of those who had not received training felt ‘completely’ or ‘fairly’ confident in identifying PNOCD. This highlights a potential gap in professionals’ self-awareness, as they rate professional inability to recognise PNOCD as the most important barrier to parents accessing support yet feel confident themselves in recognising PNOCD without training.

Parents’ knowledge and awareness was ranked among the barriers that were second most important and amenable to change. Parents being unaware of services and not having the knowledge to recognise PNOCD were seen as the barriers significantly most important and amenable to change within this cluster. This suggests that professionals perceive that parents may need more education and information around what support services are on offer and increased mental health literacy to be able to recognise PNOCD in themselves. Research focusing on OCD outside of the perinatal period has found that it takes on average 6.9 years after the onset of the disorder for individuals to seek professional support (Albert et al., Reference Albert, Barbaro, Bramante, Rosso, De and Maina2019). The present study suggests professionals believe that patients’ lack of recognition of their PNOCD creates barriers to help-seeking and accessing EBPT. This mirrors Mulcahy and colleagues’ (Reference Mulcahy, Long, Morrow, Galbally, Rees and Anderson2023) findings where professionals endorsed statements that psychoeducation of parents is a barrier to PNOCD assessment and treatment. Previous research has found that PNOCD involving sexual or harm-related obsessions are poorly recognised and highly stigmatised, while contamination-related PNOCD is more readily recognised and regarded similarly to post-partum depression (Cooke et al., Reference Cooke, McCarty, Budd, Ordway, Roussos-Ross, Mathews, McNamara and Guastello2024). Therefore, increased recognition of PNOCD has been associated with lower stigma and is crucial for access to evidence-based treatments (Cooke et al., Reference Cooke, McCarty, Budd, Ordway, Roussos-Ross, Mathews, McNamara and Guastello2024). A similarly ranked barrier, the third most important and fourth most amenable to change, was parents’ attitudes to mental health problems. Parents’ lack of disclosure or help-seeking due to feelings of shame was ranked as the barrier that was most important and amenable to change within this cluster. This aligns with previous research in which stigma and shame have been found to be a barrier to seeking treatment for OCD (Glazier et al., Reference Glazier, Wetterneck, Singh and Williams2015; Vuong et al., Reference Vuong, Gellatly, Lovell and Bee2016). Previous research has found that delivering psychoeducation to women on harm-related intrusive thoughts significantly increased disclosure of such thoughts and significantly decreased shame (Melles and Keller-Dupree, Reference Melles and Keller-Dupree2023).

The barrier of treatment challenges was rated as the least important and the second least amenable to change. This could be as within the UK treatments follow NICE guidelines; in order to achieve NICE guideline status, therapies undergo rigorous assessments to ensure there is an evidence base of efficacy (NICE, 2013). Thus, this strong evidence base may be why professionals view this as the least important barrier, or in fact, not even a barrier. Furthermore, due to the rigour of achieving NICE status, it would also be one of the most difficult factors to change.

A systematic review looking at barriers to accessing support for perinatal mental health issues has identified healthcare professionals’ rude or disinterested attitudes as a barrier to treatment (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare, Roberts, Alderdice, Coates and Hogg2021). Contrary to this research, our research suggests that professionals do not perceive this barrier to be among the most important factors contributing to access. Furthermore, an integrative review of midwives’ perspectives of caring for women experiencing perinatal mental health problems identified time constraints and lack of continuity of care as a major barrier to effective support (Noonan et al., Reference Noonan, Doody, Jomeen and Galvin2017). However, in the present research, system characteristics including time constraints were identified as less important in comparison with other barriers. This suggests that the barriers most pertinent to accessing support for PNOCD may be different from those experienced more widely across perinatal mental health conditions.

Strengths and limitations

This study is strengthened by recruiting a wide range of professionals, across a wide range of specialities, and as a result reflecting perspectives across pathways of access to EBPT. A particular strength is that professionals were recruited from perinatal services, who have specific expertise delivering support to perinatal populations, and non-perinatal services that interact, albeit less regularly, with perinatal populations. This sampling approach allowed for the inclusion of professionals with a limited perinatal experience, which will have impacted responses and subsequently the results. However, incorporating the perspectives of professionals with varying levels of experience in dealing with PNOCD, yet who interact with perinatal populations, likely makes the findings more robust due to ensuring heterogeneity in experiences and responses. By sampling a wide array of professionals, this research portrays, as best as possible, the current landscape of accessing support within the NHS for PNOCD. However, a limitation was that only a very small number of GPs were recruited and thus their perspectives are poorly represented. GPs represent an opportunity to shape access to appropriate mental health support; two in five GP appointments now include discussions on mental health (Mind, 2018) and most people experiencing OCD seek help from their GP (Vuong et al., Reference Vuong, Gellatly, Lovell and Bee2016), therefore this group of professionals may be key in improving recognition and signposting to other parts of the treatment pathway. The research is further limited by not including the perspectives of people experiencing PNOCD.

Another key strength of this study is the use of ranking to order barriers in order of importance and amenability to change. Ranking generates clarity with regard to what professionals consider to be of the highest priority, thus enabling recommendations for improving access to psychological treatments for PNOCD to be targeted for intervention development.

Further limitations include that the order of barriers and clusters presented in the survey was not randomised, but fixed. This may have had some impact on the way in which professionals ranked the barriers, due to order effect and response fatigue (Egleston et al., Reference Egleston, Miller and Meropol2011; Strack, Reference Strack, Schwarz and Sudman1992). Second, some clusters presented up to nine barriers and some may have struggled to consider this many barriers and discriminate between them. The research is also limited due to a focus on barriers rather than on an asset-based approach by focusing on facilitators. Our approach identified current difficulties within accessing support for PNOCD, but did not indicate which factors professionals see as important to continue practising in order to facilitate access. Furthermore, the survey was lengthy and did not include any reimbursement, which meant that there was a high amount of incomplete responses. The research is limited as a list-wise deletion approach was used, as survey responses were not analysed unless the participant had ranked all clusters. Chi-square tests showed that participants included in the analysis were more likely to work in perinatal services, report having worked with more people with PNOCD and done so more frequently. This may be because it is expected to be due to those professionals who worked in perinatal services and subsequently had worked with individuals experiencing PNOCD more often, and would be more engaged to complete the survey. As such, the high rate of attrition limits the results as potentially different barriers may have been prioritised if a higher proportion of non-perinatal professionals had completed the survey; this study has not captured the perspectives of professionals across the whole access pathway. A final limitation is that a power analysis for the Friedman’s test was not conducted, and therefore the results should be viewed as exploratory and potentially under-powered. Additionally, the subgroup analysis was conducted using a small sample, thus there are reduced defined effects and further research with larger samples are required to draw firmer conclusions.

Research and practice implications

Future research could compare our results with the prioritisation of barriers of people with PNOCD in order to increase confidence in the identification of prioritised barriers. Specific recommendations are needed as to how to mitigate the barriers that professionals have identified as important in improving psychological treatment access for PNOCD, and amenable to change. These recommendations, which would have intentions to be implemented as policy or interventions, should be co-produced with professionals and patients. Experience-based co-design is quickly becoming essential within health research as it results in innovation with better health outcomes compared with service-led design, benefiting patients and allowing innovation within the services (Fylan et al., Reference Fylan, Tomlinson, Raynor and Silcock2021; Steen et al., Reference Steen, Manschot and De Koning2011).

Increased professional training on PNOCD, particularly recognising and assessing PNOCD symptoms, could be developed. It is suggested that this training be co-produced with professionals in order to enhance its relevance to the professional population through suiting their needs and strengths (Clark, Reference Clark2015). However, previous research suggests there are barriers to engaging healthcare professionals in professional development and training such as motivation, ability to learn and perceived relevance of the topic to their practice (Haywood et al., Reference Haywood, Pain, Ryan and Adams2012). There is also a necessity for increased awareness within the perinatal population to identify PNOCD and to be informed about available services; frontline HCP could distribute this information during appointments, for example as written leaflets. Interventions aimed at reducing feelings of shame and stigma about mental health issues are additionally indicated to promote help-seeking (Clement et al., Reference Clement, Schauman, Graham, Maggioni, Evans-Lacko, Bezborodovs, Morgan, Rüsch, Brown and Thornicroft2015; Ferrari, 2016; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Huang, Kösters, Staiger, Becker, Thornicroft and Rüsch2018).

The impact of stigma and shame to help-seeking identifies a gap with respect to public health intervention in the form of awareness-raising to increase parents’ mental health literacy and improve their understanding of PNOCD specifically. Previous public health interventions have been found to increase recognition and awareness in conditions such as strokes (Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Bell and Ranta2019). Furthermore, interventions such as Time to Change, have been effective at reducing stigma around mental health (Evans-Lacko et al., Reference Evans-Lacko, Corker, Williams, Henderson and Thornicroft2014). Therefore, such an approach could help to reduce feelings of shame and increase mental health help-seeking for PNOCD.

Conclusions

This is the first known study to investigate professional prioritisation of barriers to evidence-based psychological therapies for PNOCD. Professional training and knowledge of PNOCD was ranked as the barrier that is most important and amenable to change. Therefore, efforts should be focused on professional training to increase knowledge, recognition, and accurate assessment of PNOCD in order to improve access for this population. Further research efforts should focus on co-producing training interventions to improve professional knowledge of PNOCD. Parents’ knowledge and awareness and their attitudes to mental health problems and professionals and services were seen as the barriers that are second most important and amenable to change. Future research is needed to identify the most appropriate and effective awareness and attitude change interventions for parents.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465825101136.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, A.T.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding of this review from the ARC KSS.

Author contributions

All authors substantially contributed to the design of the work or acquisition, analysis, interpretation, or presentation of data and the drafting or revision of the intellectual content and approved it for publication. Alice Tunks: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Resources (equal), Software (equal), Validation (equal), Visualization (equal), Writing - original draft (lead), Writing - review & editing (equal); Elizabeth Ford: Conceptualization (equal), Funding acquisition (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing - review & editing (equal); Clio Berry: Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Funding acquisition (equal), Methodology (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing - review & editing (equal); Clara Strauss: Conceptualization (equal), Funding acquisition (equal), Methodology (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing - review & editing (equal).

Financial support

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration Kent, Surrey, Sussex, as part of funding for a PhD (grant number: NIHR 200179). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests

There are no known conflicts of interests to disclose.

Ethical standards

All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Health Research Authority (HRA; IRAS: 319602) approved on 8 February 2022. All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolment in the study. Authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.