Summations

• Individuals who are forced to leave their homeland often develop stress-related mental health issues.

• Some birds, turtles, fish, and lampreys return to their birthplace to reproduce.

• The DDCS of birds may play a role in migration/navigation, and also in human mental health issues.

Considerations

• The anatomy, cytoarchitecture, and connectivity of the dorsal diencephalic conduction system in birds has hardly been studied.

• There may exist significant differences between different bird species.

• The cytoarchitecture of specific forebrain structures in birds and mammals has yet to be compared one-to-one.

Introduction

During the last half century — that is, since the author’s career as a scientist began — tremendous progress has been made in the development of techniques by which the functioning of the brain can be investigated. This applies to living humans in terms of the development of various neuroimaging and neurostimulation techniques. Groundbreaking work has also been done in the field of (bio)chemical and molecular biological analysis. The foregoing is even more true for technical advances in the field of animal experimental research. Consider, for example, the development of optogenetic research techniques that can very specifically activate or inhibit well-defined components of neuronal circuits (Deisseroth et al., Reference Deisseroth, Feng, Majewska, Miesenböck, Ting and Schnitzer2006; Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Federici and Boulis2009). However, there is one aspect of animal research that has not changed as much: although they have been surpassed by the transgenic mouse (Mus musculus) worldwide, purebred strains of the rat (Rattus norvegicus domestica, e.g., Wistar rat) is still considered an experimental animal of choice for research in the laboratory. This is hardly surprising; among laboratory animals, the easily bred laboratory rat is incredibly well documented. For most neuroscience experiments, this subspecies has some comparison material available. Such popularity also has limitations. Some biological phenomena cannot be studied in these animals because they do not exhibit them or because they cannot be simulated in an experimental setting. That’s why it’s probably a good idea to use other types of vertebrates as test animals in neuropsychopharmacological experiments.

Recently, a review article was written by the author on the neurobiology of animal migration (Loonen, Reference Loonen2024). For research on this, the rat is actually unsuitable as an experimental animal. Flying and swimming animals have a strong advantage when it comes to migrating, because it costs them much less energy. Population migration is also seen in larger land animals such as some hoofed herbivores (wildebeest, zebra, moose, reindeer), but actually not in small rodents such as the mouse or rat. Mammals basically have three options for surviving scarcity during winter: 1. Seasonal migration, 2. lowering metabolism by heterothermy (torpor and hibernation), 3. or adjusting behaviour to tolerate food scarcity with or without winter stockpiling. Rats belong to the latter category; they do not migrate and are not cardiophysiologically equipped to hibernate (Filatova et al., Reference Filatova, Kuzmin, Guskova and Abramochkin2023). Although rats seek warmer places to stay (e.g., shelters and houses) in order to cope with the winter cold, true migration over longer distances is not observed. Birds and marine mammals can navigate using the Earth’s magnetic field. An independent sense of direction is seen in rats (Poucet et al., Reference Poucet, Chaillan, Truchet, Save, Sargolini and Hok2015), but to the author’s knowledge it has not been demonstrated that the Earth’s magnetic field plays a role here (Shirdhankar & Malkemper, Reference Shirdhankar and Malkemper2024).

Nevertheless, it should not be forgotten that modern man originally led a nomadic existence as hunter-gatherers. The domestication of animals began about 15,000 years ago (Zeder, Reference Zeder2012), and the first permanent agricultural settlements of humans occurred during the following ‘Neolithic revolution’ some 10,000 years ago (Shavit & Sharon, Reference Shavit and Sharon2023). So that’s actually very recent in human’s evolution. Therefore, studying the neurobiological mechanisms that regulate animal migration may also be relevant for understanding the (patho)physiology of, e.g., human wandering. Perhaps remnants of this can be found in the physiology of present-day humans and play a role in seasonal fluctuations in the severity of mood disorders (Dollish et al., Reference Dollish, Tsyglakova and McClung2024). Moreover, these mechanisms may also contribute to the amplified occurrence of individuals with schizophrenia (Selten et al., Reference Selten, van der Ven and Termorshuizen2020) and other mental disorders (Osman et al., Reference Osman, Ncube, Shaaban, Dafallah and Bojorquez2024) among those who migrate in modern times.

With this article, the author aims to draw attention to the possibility of using animals from classes other than Mammalia (in particular Aves) as experimental subjects in neuropsychopharmacological studies. He aims to substantiate this by outlining how various aspects of the neurobiological mechanisms underlying migration and navigation in animals may also be relevant to human behaviour. As a prerequisite for application in this context, the anatomy of the forebrain of birds must be compared in more detail with that of humans. For research into the function of the dorsal diencephalic conduction system (DDCS), birds are less suitable similar as humans. It is better to turn to the most primitive classes of vertebrates, because in these the DDCS is relatively large and less complex. Of note, previously the term “connection” rather than “conduction” was used because it better reflects the complex role of the habenula as a reciprocal connecting hub, but “conduction” is the original term (Sutherland, Reference Sutherland1982). To avoid unnecessary repetition, the author refers to previous articles (Loonen & Ivanova, Reference Loonen and Ivanova2018a, Reference Loonen and Ivanova2018b; Loonen, Reference Loonen2024) for a more detailed description and the correct references.

Animal migration

Timing of migration in birds

Of all animal species that undertake annual migrations, migratory birds are by far the best studied (Loonen, Reference Loonen2024). Millions of birds change residence each spring and fall between their wintering grounds and their higher latitude breeding grounds. The physiological changes that occur in migrants compared to conspecifics that breed in the wintering grounds (residents) have all been very well elucidated. The main determinant of timing is the ratio of day to night hours, i.e., the length of the photoperiod (Stevenson and Kumar, Reference Stevenson and Kumar2017). The circannual rhythm is regulated in migratory birds by a photosensitive centre in specific regions of the hypothalamus (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Singh and Rani2004; Natesan et al., Reference Natesan, Geetha and Zatz2002). These photosensitive neurons are coupled neither to the retina nor to the epiphysis and project onto the median eminence and the part of the adenohypophysis in close apposition to it: the pars tuberalis (PT) (Korf, Reference Korf2018). These photosensitive neurons activate a system that ultimately regulates the secretion of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) by specific hypothalamic neurons into the primary portal hypophysial circulation in the median eminence. The process involves PT-specific cells in the pars tuberalis and particular glial cells (tanycytes) lining the third ventricle at the median eminence and mediobasal hypothalamus. An essential role is played by thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH-β) secreted by PT-specific cells that induces these tanycytes to express type 2 and type 3 deiodinase (Dio2, Dio3) within the basomedial hypothalamus (Korf, Reference Korf2018; Dardente & Migaud, Reference Dardente and Migaud2021). In spring, Dio2 predominates, producing the active lyothyronine (T3) and at the end of summer Dio3 producing the inactive reverse trijiodothyronine (rT3) and diiodothyronine (T2). In parallel, GnRH release is promoted in spring and extinguishes at the end of summer. This sexual maturity (particularly in females) determines migration to and from the breeding grounds (Kimmitt, Reference Kimmitt2020).

Mammals also display this system in the ventral part of the wall of the third ventricle, but the photosensitive neurons in the hypothalamus are missing (Korf, Reference Korf2018; Dardente & Migaud, Reference Dardente and Migaud2021). Instead, the secretion of TSH-β is regulated by type 1 melatonin receptors (MT1) and depends on the secretion of the hormone melatonin by the pineal gland. The pineal gland is connected to photosensitive cells of the retina and produces melatonin at an inverse photoperiod-dependent rate. The relationship with reproduction is preserved in some mammals (sheep, goat, hamster), but the system is also preserved in species where this is less (F344 rats) or not (mouse) the case (Dardente & Migaud, Reference Dardente and Migaud2021).

When considering this endocrine regulation of migration timing, a comparison with the add-on treatment of human mood disorders comes to mind (with light, melatonin agonists, lyothyronine, and oestrogens) (Loonen & Ivanova, Reference Loonen and Ivanova2016a). It would also be interesting to conduct experimental studies in birds to investigate whether the response to pharmacological interventions depends on this circadian regulation of migratory behaviour and then translate this to treatment of humans.

Migration in mammals

Some mammals also exhibit seasonal migration. The catchiest examples of this are certain whales, which travel relatively long distances between low latitude breeding and high latitude foraging areas where they spend winter and summer, respectively (Andrews-Goff et al., Reference Andrews-Goff, Bestley, Gales, Laverick, Paton, Polanowski, Schmitt and Double2018; De Weerdt et al., Reference De Weerdt, Pacheco, Calambokidis, Castaneda, Cheeseman, Frisch-Jordán, Garita Alpízar, Hayslip, Martínez-Loustalot, Palacios, Quintana-Rizzo, Ransome, Urbán Ramírez, Clapham and Van der Stocken2023). Because relatively little food is available in the intermediate area, whales, like some songbirds, make stopovers precisely to brush up on their feeding status (Silva et al., Reference Silva, Prieto, Jonsen, Baumgartner, Santos and Anil2013).

Other animals that migrate depending on the seasons are the large hoofed mammals, ungulates, like caribou also known as (aka) reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), moose (Alces alces), wildebeest aka gnu (Connochaetes taurinus), and zebra (Equus quagga). In these animals, the reasons for this seasonal migration are: 1. the availability of higher value food, 2. the one-sided availability of essential nutrients and 3. the escape from seasonal predators, parasites and insects (Bolger et al., Reference Bolger, Newmark, Morrison and Doak2008). Evading predators is, of course, relative: migrating herds are often also followed by predators such as grey wolf (Canis lupus) that also benefit from improved nutritional status that way (Joly et al., Reference Joly, Gurarie, Sorum, Kaczensky, Cameron, Jakes, Borg, Nandintsetseg, Hopcraft, Buuveibaatar, Jones, Mueller, Walzer, Olson, Payne, Yadamsuren and Hebblewhite2019). Actually, humans can also be included in this category of active followers. This is most true of the Indigenous people who inhabited the great plains of North America and hunted the wandering herds of bison (Bison bison). More domesticated were reindeer in the case of the original inhabitants of Lapland, the Sami (or Samen). But even in this case, humans followed the herds as they migrated and not the other way around. An interesting phenomenon that occurs in these ungulates is that they apparently anticipate a later need for nutritious food. This is nicely illustrated by some caribou in Newfoundland that begin their spring migration even before the snow has largely melted away to be in an area with plenty of nutritious young greenery when they later calve and need to lactate (Laforge et al., Reference Laforge, Bonar and Vander Wal2021). Apparently in these animals, the melting of the snow is a cue to initiate migration. Although less explicitly than in migratory birds, reproduction also plays an important role in these ungulates as a reason for migration. The wildebeest are also known to tailor their annual migration to rainfall and places where food is most nutritious (Boone et al., Reference Boone, Thirgood and Hopcraft2006; Holdo et al., Reference Holdo, Holt and Fryxell2009). The latter is called following the green wave (Aikens et al., Reference Aikens, Kauffman, Merkle, Dwinnell, Fralick, Monteith and Nathan2017). However, on which internal and external cues they initiate this journey is not well known. Most likely, this is based on a cognitive process that can be incorporated into general behavioural planning.

The importance of social stimuli

The timing of migration is dependent not only on internal cues — such as the secretion TSH-β leading to that of testosterone (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Tripathi and Kumar2022) or the secretion of Ghrelin (Lupi et al., Reference Lupi, Morbey, MacDougall-Shackleton, Kaiya, Fusani and Guglielmo2022) — and external cues (such as the melting of snow (Laforge et al., Reference Laforge, Bonar and Vander Wal2021)), but to a significant extent also on social cues (Guttal & Couzin, Reference Guttal and Couzin2010; Oestreich et al., Reference Oestreich, Aiu, Crowder, McKenna, Berdahl and Abrahms2022; Reyes & Szewczak, Reference Reyes and Szewczak2022). Oestreich and colleagues (2022) distinguish six mutually non-exclusive types of social interactions between conspecifics that determine this timing in different animal species (mainly vertebrates). Following this, it can be postulated that the timing of migration is controlled by three concurrent processes embedded in a reasonably flexible cognitive procedure: 1. the perception and response to internal and external cues by (any) trail seeking individuals; 2. the social interactions between these trail seeking individuals and the rest of the population, and 3. the added value that the social interactions bring to the adequate and specific response to internal and external cues of the trail seekers. This timing and possibly the route and destination can be adapted to climate change and human-induced barriers by influencing some of the individuals as previously suggested in Loonen (Reference Loonen2024). Such changes in migration behaviour may also occur spontaneously. This may be concluded from research on short-term changes in the breeding area and route taken by the pink-footed goose (Anser brachyrhynchus) (Madsen et al., Reference Madsen, Schreven, Jensen, Johnson, Nilsson, Nolet and Pessa2023).

Animal navigation

Route determination

The study by Madsen et al. (Reference Madsen, Schreven, Jensen, Johnson, Nilsson, Nolet and Pessa2023) reveals another insight: apparently, the choice of route is variable. The original flight route of the pink-footed goose was from northern Denmark across Norway to Svalbard in the Arctic Ocean, some 565 km north of Norway. As this route became less attractive, some animals flew a stretch with the migration route of the taiga bean goose (Anser f. fabalis) over Sweden and its staging areas on the Swedish Bothnian coast to its breeding grounds in northern Fennoscandia. Some pink-footed geese previously deviated from this flight route during spring migration to fly to their original breeding grounds on Svalbard, but others flew on to a new breeding area in Novaya Zemlya in northern Russia. The latter group increased in 10 years to 3000 (spring)-4000 (autumn) specimens (Madsen et al., Reference Madsen, Schreven, Jensen, Johnson, Nilsson, Nolet and Pessa2023). That social interactions with conspecifics are very important for juvenile migration is also shown by the research of Loonstra et al. (Reference Loonstra, Verhoeven, Both and Piersma2023). They machine-hatched eggs from nests of the black-tailed godwit (Limosa limosa limosa) and hand-raised these specimens. In autumn they released siblings in the area of origin (Netherlands) or 1000 km east (Poland) and monitored the route they chose. It turned out that for the most part they followed the route of the local birds in the area where they were released. Interestingly, something similar may also be the mechanism by which the pink-footed goose got to Novaya Zemlya (Madsen et al., Reference Madsen, Schreven, Jensen, Johnson, Nilsson, Nolet and Pessa2023). Some taiga bean geese undertake a molt migration from Finland to Novaya Zemlya and pink-footed geese may have flown with them. In this way, the new breeding area may have been actively discovered by these birds.

The multi-annual variability of bird migratory movements shows that the route chosen is much less precisely fixed than the timing of departure (Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, MacPherson, Fraser, McKinnon, Stutchbury and Mettke-Hofmann2012). Inter-individual variability is also significant (Pancerasa et al., Reference Pancerasa, Ambrosini, Romano, Rubolini, Winkler and Casagrandi2022). This constitutes an indication that the emotional and cognitive interpretation of variable sensory information plays a greater role in route determination than in departure timing. It appears that the route is mainly calculated by means of a cognitive neural process and that the timing of departure is mainly regulated by a neuroendocrine emotional process (Loonen, Reference Loonen2024). Migratory birds combine information about the position and strength of magnetic field lines with that about the position of celestial bodies and that of the landscape (Åkesson and Bianco, Reference Åkesson and Bianco2017; Muheim et al., Reference Muheim, Schmaljohann and Alerstam2018).

Sensitivity to earth’s magnetic field

A large number of living creatures are sensitive to the Earth’s magnetic field, i.e., exhibit magnetoreception; these include plants (Galland & Pazur, Reference Galland and Pazur2005), microorganisms (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Kirschvink, Paterson, Bazylinski and Pan2020; Monteil & Lefevre, Reference Monteil and Lefevre2020), insects (Fleischmann et al., Reference Fleischmann, Grob and Rössler2020), fish (Formicki et al., Reference Formicki, Korzelecka-Orkisz and Tański2019; Naisbett-Jones & Lohmann, Reference Naisbett-Jones and Lohmann2022), birds (Mouritsen & Ritz, Reference Mouritsen and Ritz2005; Wiltschko & Wiltschko, Reference Wiltschko and Wiltschko2019) and several species of mammals (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Kirschvink, Ahmed and Dizon1992; Kremers et al., Reference Kremers, López Marulanda, Hausberger and Lemasson2014; Caspar et al., Reference Caspar, Moldenhauer, Moritz, Němec, Malkemper and Begall2020; Zhang & Malkemper, Reference Zhang and Malkemper2023). Several indications exist that humans too are capable of magnetoreception (Baker, Reference Baker1987; Carrubba et al., Reference Carrubba, Frilot, Chesson, Webber, Zbilut and Marino2008; Foley et al., Reference Foley, Gegear and Reppert2011; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Hilburn, Wu, Mizuhara, Cousté, Abrahams, Bernstein, Matani, Shimojo and Kirschvink2019; Chae et al., Reference Chae, Kim, Kwon and Kim2022), but that interference with this perception occurs by low-level anthropogenic electromagnetic fields and leads to medical problems is controversial (Henshaw & Philips, Reference Henshaw and Philips2024). Two forms of magnetosensing are involved in birds: one via cryptochrome and the other via magnetite (Johnsen & Lohmann, Reference Johnsen and Lohmann2005; Mouritsen & Ritz, Reference Mouritsen and Ritz2005; Clites & Pierce, Reference Clites and Pierce2017; Wiltschko & Wiltschko, Reference Wiltschko and Wiltschko2019). However, these theories are recently heavily criticised by Panagopoulos et al. (Reference Panagopoulos, Karabarbounis and Chrousos2024), who argue that specific magnetosensitive organs are not needed at all to enable sensitivity to the geomagnetic influence. This will be left aside here.

Cryptochromes belong to a family of photolyases/cryptochromes (PHR/CRY) that are very widespread in living nature and are involved in a wide range of processes (Ozturk, Reference Ozturk2017). They are flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-bearing flavoproteins (Calloni & Vabulas, Reference Calloni and Vabulas2023), which in vertebrates also play a role in repression of genetic expression and in reentrainment of the circadian clock (Parico & Partch, Reference Parico and Partch2020; DeOliveira & Crane, Reference DeOliveira and Crane2024). Of particular interest are cryptochrome 1 (Cry1a and Cry1b), cryptochrome 2 (cry2) and cryptochrome 4 (Cry4a and Cry4b) and these are found in birds mainly in the retina and also in the pineal gland (Nagy & Csernus, Reference Nagy and Csernus2007; Rotov et al., Reference Rotov, Goriachenkov, Cherbunin, Firsov, Chernetsov and Astakhova2022; Wiltschko & Wiltschko, Reference Wiltschko and Wiltschko2019). The sensitivity to the Earth magnetic field is attributed to the difference in the spin of unpaired electrons upon the recoil of FADH· radicals from the FAD cofactor of these cryptochromes (Hore and Mouritsen, Reference Hore and Mouritsen2016; Karki et al., Reference Karki, Vergish and Zoltowski2021; Zhang & Malkemper, Reference Zhang and Malkemper2023; DeOliveira & Crane, Reference DeOliveira and Crane2024). The presence in cones in the retina would thus make it sensitive to the direction of the field lines of the geomagnetic field, which in turn depends on its position on Earth (Mouritsen & Ritz, Reference Mouritsen and Ritz2005; Rotov et al., Reference Rotov, Goriachenkov, Cherbunin, Firsov, Chernetsov and Astakhova2022; Wiltschko & Wiltschko, Reference Wiltschko and Wiltschko2019; Wiltschko et al., Reference Wiltschko, Nießner and Wiltschko2021).

Magnetite involves very small particles (called nanoparticles) of iron (II, III) oxide (Fe3O4), which can orient themselves in a magnetic field (Cadiou & McNaughton, Reference Cadiou and McNaughton2010; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Boyd, House, Woodward, Mathes, Cowin, Saunders and Baer2015). Magnetite crystals of 50-100 nm are permanently magnetised and are called “magnetic single-domain” particles. Assemblies of crystals up to 50 nm are “superparamagnetic” particles, that is, they are magnetisable by an external magnetic field but lose this property when this field is absent (Cadiou & McNaughton, Reference Cadiou and McNaughton2010). These particles are found in nerve endings in the skin over the rim of the upper beak of homing pigeons (Fleissner et al., Reference Fleissner, Stahl, Thalau, Falkenberg and Fleissner2007), belonging to the ophthalmic nerve branch of the trigeminal nerve (Heyers et al., Reference Heyers, Zapka, Hoffmeister, Wild and Mouritsen2010). The specialised epithelium of the lagena of the inner ear has also been mentioned as a possible carrier of magnetoreceptors (Wu & Dickman, Reference Wu and Dickman2011), but later research found no evidence for the presence of magnetite in this structure (Malkemper et al., Reference Malkemper, Kagerbauer, Ushakova, Nimpf, Pichler, Treiber, de Jonge, Shaw and Keays2019). Magnetite-containing receptors could be sensitive to geomagnetic field strength and incorporate this information into a map of the landscape.

Little research has been done into whether and what role the perception of the Earth’s magnetic field plays in regulating neurochemical and neuropharmacological processes in humans. To distinguish this sensitivity from that for other types of magnetic fields, we could perhaps look at how this works in birds.

Comparison of the avian to the mammalian cerebrum

Birds can be quite good models for certain processes that also occur in humans. However, a major problem exists: the forebrain is built differently and the differences were interpreted differently in the first half of last century (Loonen, Reference Loonen2024). Reiner et al. (Reference Reiner, Perkel, Bruce, Butler, Csillag, Kuenzel, Medina, Paxinos, Shimizu, Striedter, Wild, Ball, Durand, Gütürkün, Lee, Mello, Powers, White, Hough, Kubikova, Smulders, Wada, Dugas-Ford, Husband, Yamamoto, Yu, Siang and Jarvis2004) describe that it was not until 2002 that a new nomenclature was adopted in which the misleading concept that the avian hemispheres consist almost entirely of striatal areas was abandoned.

Joint ancestry

Birds and mammals are both descended from the same extinct captorhinomorphs (Butler, Reference Butler1994). From this ancestor developed synapsids on the one hand and non-synapsids (diapsids) and turtles on the other. All reptiles (except turtles) evolved from the diapsid group and birds are a late offshoot of this group. From the synapsids later emerged the mammals. In birds and mammals, the forebrain developed differently (Butler, Reference Butler1994). In mammals a lining emerged with a six-layered neocortex and in birds this became a dorsal ventricular ridge (DVR) and the so-called Wulst with a different structure. Although they grew differently in birds and mammals, all structures of the captorhinomorph ancestor are found in the forebrain of both birds and mammals.

Anatomical differences

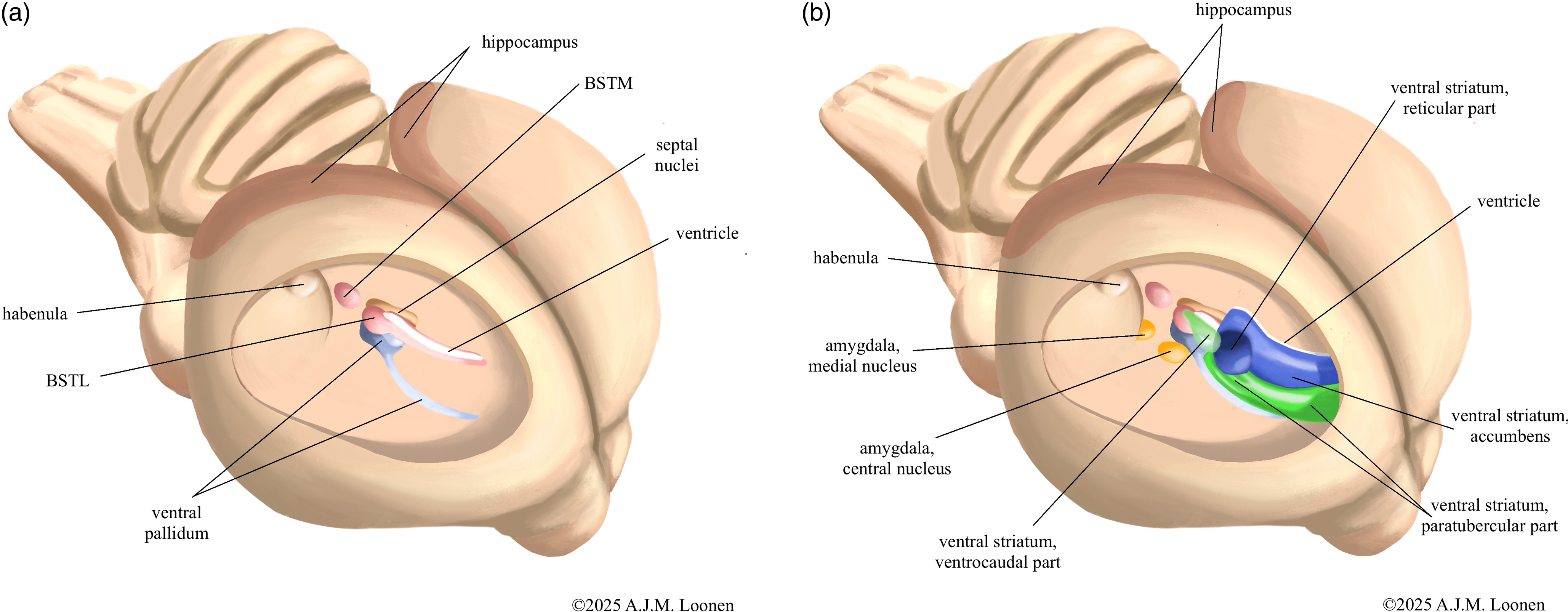

The greatest differences in blueprint exist at the forebrain level and involve the basal ganglia, dorsal thalamus, and the so-called pallial structures; as described in detail by the author in an earlier article (Loonen, Reference Loonen2024). Paraphrased in simpler terms, the differences boil down to the fact that in birds the forebrain structures involved in the processing of visual, acoustic and balance sensory information (collothalamic) are developed more than those for somatosensory and visceral data (lemnothalamic) (Butler, Reference Butler1994). In mammals, this development does not appear to be that unilateral. It is easy to imagine how this translated into functional differences. Regarding the basal ganglia, gross anatomical differences exist mainly in the dorsal striatopallidum (Kuenzel et al., Reference Kuenzel, Medina, Csillag, Perkel and Reiner2011). Anatomically, the amygdaloid and ventral striatopallida of birds and mammals are apparently reasonably similar (Abellán & Medina, Reference Abellán and Medina2009; Bruce et al., Reference Bruce, Erichsen and Reiner2016). To illustrate this, the relative position of these phylogenetically older structures in the ventral hemisphere is shown schematically in Fig. 1. More differences are described at the microscopic level (Abellán & Medina, Reference Abellán and Medina2009; Kuenzel et al., Reference Kuenzel, Medina, Csillag, Perkel and Reiner2011; Bruce et al., Reference Bruce, Erichsen and Reiner2016; Medina et al., Reference Medina, Abellán, Morales, Pross, Metwalli, González-Alonso, Freixes and Desfilis2023), but the author found no direct, one-to-one comparative studies examining the extent of these differences. As for tissues derived from the pallium, the differences are quite significant (Medina et al., Reference Medina, Abellán, Morales, Pross, Metwalli, González-Alonso, Freixes and Desfilis2023). This includes structures that do not derive from the dorsal pallium, such as the corticoid amygdala (Hanics et al., Reference Hanics, Teleki, Alpár, Székely and Csillag2017; Medina et al., Reference Medina, Abellán, Morales, Pross, Metwalli, González-Alonso, Freixes and Desfilis2023) and the hippocampus (Atoji et al., Reference Atoji, Sarkar and Wild2016; Striedter, Reference Striedter2016) (see Fig. 1). So this goes far beyond just for DVR and Wulst (Belgard et al., Reference Belgard, Montiel, Wang, García-Moreno, Margulies, Ponting and Molnár2013).

Figure 1. Insight view into the right hemisphere of pigeon’s brain with schematic representation of the amygdaloid and ventral pallidum (A) and striatopallidum (B). The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis is shown here as a separate amygdaloid pallidum and the nuclear amygdala as a separate amygdaloid striatum, but in reality these structures are cytologically and anatomically highly intertwined. Parts of the medial striatum that may also be homologues of the core and shell portion of the ventral striatum are not shown. The paratubercular and ventrocaudal striatal regions can be considered the shell of the ventral striatum. The nature of the shown reticular portion of the ventral striatum is uncertain. BSTM - medial bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, BSTL - lateral bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Adapted from figures by Bruce et al. (Reference Bruce, Erichsen and Reiner2016) and Medina et al., Reference Medina, Abellán, Morales, Pross, Metwalli, González-Alonso, Freixes and Desfilis2023.

Functional similarities

Despite these anatomical differences between mammals and birds, relevant similarities exist at a more fundamental level in the wiring that plays a role in the function of different brain structures (Atoji et al., Reference Atoji, Sarkar and Wild2016; Güntürkün et al., Reference Güntürkün, von Eugen, Packheiser and Pusch2021; Jarvis et al., Reference Jarvis, Yu, Rivas, Horita, Feenders, Whitney, Jarvis, Jarvis, Kubikova, Puck, Siang-Bakshi, Martin, McElroy, Hara, Howard, Pfenning, Mouritsen, Chen and Wada2013; Smulders, Reference Smulders2017; Herold et al., Reference Herold, Schlömer, Mafoppa-Fomat, Mehlhorn, Amunts and Axer2019). It are precisely these similarities despite all anatomical differences that make birds particularly interesting as experimental animals. Some bird species are remarkably intelligent (Bugnyar, Reference Bugnyar2024; Güntürkün et al., Reference Güntürkün, Pusch and Rose2024). As indicated in section 3.1, navigational ability is a highly developed cognitive skill in various bird species. Contrary to previous thinking (see Nevitt and Hagelin, Reference Nevitt and Hagelin2009), the sense of smell is also significantly developed in at least some bird species (Prada & Furton, Reference Prada and Furton2018; Gagliardo & Bingman, Reference Gagliardo and Bingman2024). This is not very different from humans, where smell as a sense also co-determines emotional behaviour (Rolls, Reference Rolls2019; Bratman et al., Reference Bratman, Bembibre, Daily, Doty, Hummel, Jacobs, Kahn, Lashus, Majid, Miller, Oleszkiewicz, Olvera-Alvarez, Parma, Riederer, Sieber, Williams, Xiao, Yu and Spengler2024) and also plays a role in cognitive functioning (Green et al., Reference Green, Reid, Kneuer and Hedgebeth2023; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Xiao, Tong, Dong, Chen and Xu2024). Therefore, it might be an interesting challenge to use birds as experimental animals in biobehavioural research questions, including those related to cognitive functioning and consciousness.

Dorsal diencephalic conduction system (DDCS)

Relevance of using birds in studying DDCS

At first glance, birds seem less suitable as experimental animals for investigating the role of the dorsal diencephalic conduction system (DDCS) in regulating anxiety and mood (Loonen & Ivanova, Reference Loonen and Ivanova2018a, Reference Loonen and Ivanova2018b, Reference Loonen and Ivanova2019a; Loonen et al., Reference Loonen, Ochi, Geers, Simutkin, Bokhan, Touw, Wilffert, Kornetov and Ivanova2021) and in addiction (Loonen et al., Reference Loonen, Schellekens and Ivanova2016; Batalla et al., Reference Batalla, Homberg, Lipina, Sescousse, Luijten, Ivanova, Schellekens and Loonen2017; Loonen, Reference Loonen2024). This system connects various structures of the forebrain to important monoaminergic and cholinergic centres of the upper brainstem (Batalla et al., Reference Batalla, Homberg, Lipina, Sescousse, Luijten, Ivanova, Schellekens and Loonen2017; Metzger et al., Reference Metzger, Souza, Lima, Bueno, Gonçalves, Sego, Donato and Shammah-Lagnado2021; Loonen & Ivanova, Reference Loonen and Ivanova2022). Via ascending efferent fibres, these upper brainstem centres in turn selectively regulate the activity of the various components of the forebrain. Along these lines, the DDCS determines response flexibility in social, defensive, and appetitive contexts. A well-known example is the role of fibres running from the pallidum to the lateral habenula that regulate whether behaviour continues or is aborted in lampreys (Stephenson-Jones et al., Reference Stephenson-Jones, Kardamakis, Robertson and Grillner2013). These fibres — which are known to co-transmit glutamate and GABA (Meye et al., Reference Meye, Soiza-Reilly, Smit, Diana, Schwarz and Mameli2016; Kim & Sabatini, Reference Kim and Sabatini2023; Shabel et al., Reference Shabel, Proulx, Piriz and Malinow2014) — probably play a similar role in obsessive–compulsive disorder (Loonen & Ivanova, Reference Loonen and Ivanova2019b). A problem in studying the role of the DDCS in regulating human behaviour is that in humans this system is very small and still complex in composition. The habenula consists of a lateral (∼ 94%) and a medial (∼ 6%) division (Díaz et al., Reference Díaz, Bravo, Rojas and Concha2011) and in humans measures only 15–30 mm3 on each side of the midline (Batalla et al., Reference Batalla, Homberg, Lipina, Sescousse, Luijten, Ivanova, Schellekens and Loonen2017; Loonen & Ivanova, Reference Loonen and Ivanova2022). Nevertheless, the habenula consists of a large number of different nuclei and regions that differ in terms of connections and chemoarchitecture (Loonen & Ivanova, Reference Loonen and Ivanova2022). To the best of my knowledge, the DDCS of birds is still chronically understudied in comparison to other classes of animals. There is some evidence for the presence of major components of the DDCS in birds (e.g., Medina & Reiner, Reference Medina and Reiner1994, Reference Medina and Reiner1997). However many important details about the anatomy and chemoarchitecture of this system in birds still need to be clarified. Other important details of the DDCS such as the exact course of the fasciculus retroflexus, which is the bundle of fibres connecting the habenula to the brainstem have only been described recently (Ferran & Puelles, Reference Ferran and Puelles2024). Thus, it is important to further investigate the avian DDCS as well as to determine its role in navigation and magnetosensing (Loonen, Reference Loonen2024), because these functions may be less developed in mammals used as animal models for mental diseases. Any residues of this avian functionality in humans can then be better targeted and tested out.

Possible alternative as experimental animal

The DDCS is phylogenetically very old. The habenula is already present in an evolutionary ancestor of the first vertebrates (Loonen, Reference Loonen2024). These first vertebrates from 560 million years ago had a central nervous system (CNS) similar to that of the present-day lamprey. Although relatively small compared to the rest of the CNS, the forebrain of the lamprey is composed of the same components as the forebrain of humans, although of course the proportions have considerably changed and several ‘newer parts’ have developed (Loonen & Ivanova, Reference Loonen and Ivanova2015, Reference Loonen and Ivanova2016b). The DDCS occupies a relatively large portion of the forebrain in the lamprey (Robertson et al., Reference Robertson, Kardamakis, Capantini, Pérez-Fernández, Suryanarayana, Wallén, Stephenson-Jones and Grillner2014; Grillner, Reference Grillner2021). This makes it interesting to investigate the mono- and polysynaptic afferent and efferent part of the DDCS under the use of advanced neuropharmacological research techniques. The anatomy and cytoarchitecture can indeed be studied well in the relatively simple brain of the lamprey. However, the precise function is more difficult to determine because DDCS’s possible significance in behavioural experiments has not yet been fully explored. The precise significance of this connectivity can, therefore, better be verified in zebrafish (Danio rerio). It should be noted, however, that these ray-finned fish have an everted instead of inverted forebrain which changes the anatomical relationships (Mueller, Reference Mueller2022; Nieuwenhuys, Reference Nieuwenhuys2009). Zebrafish are an excellent model for studying the genetic, neurochemical and pharmacological underpinnings of mental disorders (Meng et al., Reference Meng, Yang, Liao, Sun, Su and Mei2025) such as anxiety disorders (Golushko et al., Reference Golushko, Matrynov, Galstyan, Apukhtin, de Abreu, Yang, Stewart and Kalueff2025) and autism (Jiao et al., Reference Jiao, Xu, Tian, Zhou, Chen and Wang2024). Furthermore, the involvement of the habenula in zebrafish in such processes has been investigated previously (Agetsuma et al., Reference Agetsuma, Aizawa, Aoki, Nakayama, Takahoko, Goto, Sassa, Amo, Shiraki, Kawakami, Hosoya, Higashijima and Okamoto2010; Andalman et al., Reference Andalman, Burns, Lovett-Barron, Broxton, Poole, Yang, Grosenick, Lerner, Chen, Benster, Mourrain, Levoy, Rajan and Deisseroth2019). By combining this with findings in lampreys, the mechanism can be refined further. This author has previously suggested, quite rightly, that the lamprey should also be recognised as a suitable experimental animal for the regulation of human behaviour (Loonen & Ivanova, Reference Loonen and Ivanova2018a).

Why recommend using birds and lampreys in animal models for human mental disorders?

The question may arise as to why it is at all interesting to look at the brains of “early” vertebrates such as lampreys and non-mammalian “late” vertebrates such as birds in order to gain insight into the pathophysiology and pharmacology of human mental disorders. Its relevance may lie in the presence or absence of consciousness. Now I want to steer clear of the age-old discussion of what consciousness actually is, which takes place in a combination of neuroscientific and philosophical domains (León & Zahavi, Reference León and Zahavi2023; Wagner-Altendorf, Reference Wagner-Altendorf2023; Kozuch, Reference Kozuch2024). For this article, I want to limit myself to the personal view that consciousness is the human mind capacity that enables the individual to perceive and define oneself by translating perceptions of the external world into strictly personal thoughts and sensations. According to the classical view, a properly functioning cerebral cortex is essential for having and maintaining consciousness (Koch, Reference Koch2018; Nieder, Reference Nieder2021). However, some birds — members of the corvid songbird family (crows, ravens, jays) — exhibit cognitive abilities that also indicate the presence of consciousness (Güntürkün, Reference Güntürkün2021; Nieder, Reference Nieder2021). Reptiles and amphibians do not have these and thus probably do not have consciousness (Nieder, Reference Nieder2022). In humans, consciousness is at least partly responsible for the onset and manifestations of mental disorders. However, the cerebral cortex (neocortex, isocortex) of humans is so extensive that the significance for the emergence of specific mental disorders has a large number of degrees of freedom. This makes the interpretation of large neuroimaging studies aimed at finding cortical abnormalities in, for example, individuals with schizophrenia (Van Erp et al., Reference van Erp, Walton, Hibar, Schmaal, Jiang, Glahn, Pearlson, Yao, Fukunaga, Hashimoto, Okada, Yamamori, Bustillo, Clark, Agartz, Mueller, Cahn, de Zwarte, Hulshoff Pol, Kahn, Ophoff, van Haren, Andreassen, Dale, Doan, Gurholt, Hartberg, Haukvik, Jørgensen, Lagerberg, Melle, Westlye, Gruber, Kraemer, Richter, Zilles, Calhoun, Crespo-Facorro, Roiz-Santiañez, Tordesillas-Gutiérrez, Loughland, Carr, Catts, Cropley, Fullerton, Green, Henskens, Jablensky, Lenroot, Mowry, Michie, Pantelis, Quidé, Schall, Scott, Cairns, Seal, Tooney, Rasser, Cooper, Shannon Weickert, Weickert, Morris, Hong, Kochunov, Beard, Gur, Gur, Satterthwaite, Wolf, Belger, Brown, Ford, Macciardi, Mathalon, O’Leary, Potkin, Preda, Voyvodic, Lim, McEwen, Yang, Tan, Tan, Wang, Fan, Chen, Xiang, Tang, Guo, Wan, Wei, Bockholt, Ehrlich, Wolthusen, King, Shoemaker, Sponheim, De Haan, Koenders, Machielsen, van Amelsvoort, Veltman, Assogna, Banaj, de Rossi, Iorio, Piras, Spalletta, McKenna, Pomarol-Clotet, Salvador, Corvin, Donohoe, Kelly, Whelan, Dickie, Rotenberg, Voineskos, Ciufolini, Radua, Dazzan, Murray, Reis Marques, Simmons, Borgwardt, Egloff, Harrisberger, Riecher-Rössler, Smieskova, Alpert, Wang, Jönsson, Koops, Sommer, Bertolino, Bonvino, Di Giorgio, Neilson, Mayer, Stephen, Kwon, Yun, Cannon, McDonald, Lebedeva, Tomyshev, Akhadov, Kaleda, Fatouros-Bergman, Flyckt, Busatto, Rosa, Serpa, Zanetti, Hoschl, Skoch, Spaniel, Tomecek, Hagenaars, McIntosh, Whalley, Lawrie, Knöchel, Oertel-Knöchel, Stäblein, Howells, Stein, Temmingh, Uhlmann, Lopez-Jaramillo, Dima, McMahon, Faskowitz, Gutman, Jahanshad, Thompson, Turner, Farde, Flyckt, Engberg, Erhardt, Fatouros-Bergman, Cervenka, Schwieler, Piehl, Agartz, Collste, Victorsson, Malmqvist, Hedberg and Orhan2018) or depression (Schmaal et al., Reference Schmaal, Hibar, Sämann, Hall, Baune, Jahanshad, Cheung, van Erp, Bos, Ikram, Vernooij, Niessen, Tiemeier, Hofman, Wittfeld, Grabe, Janowitz, Bülow, Selonke, Völzke, Grotegerd, Dannlowski, Arolt, Opel, Heindel, Kugel, Hoehn, Czisch, Couvy-Duchesne, Rentería, Strike, Wright, Mills, de Zubicaray, McMahon, Medland, Martin, Gillespie, Goya-Maldonado, Gruber, Krämer, Hatton, Lagopoulos, Hickie, Frodl, Carballedo, Frey, van Velzen, Penninx, van Tol, van der Wee, Davey, Harrison, Mwangi, Cao, Soares, Veer, Walter, Schoepf, Zurowski, Konrad, Schramm, Normann, Schnell, Sacchet, Gotlib, MacQueen, Godlewska, Nickson, McIntosh, Papmeyer, Whalley, Hall, Sussmann, Li, Walter, Aftanas, Brack, Bokhan, Thompson and Veltman2017) extremely difficult. The lack of an advanced and well-developed dorsal pallium makes the cognitive interpretation of sensory information impossible. It may be assumed therefore that “early” vertebrates such as the lamprey perceive the external world by having emotional sensations such as fear, pain, gloom without the accompanying awareness. According to this author, this makes it likely that these emotions are also generated in humans in the so-called ‘primary’ forebrain (amygdaloid and hippocampal complexes, the hypothalamus, septal nuclei, and habenula). Indeed, lampreys must be able to perceive the external environment, because they are able to respond appropriately to an unsafe environment. Neurobiology can be examined in these early vertebrates without the modulation (and sensation) by the cerebral cortex that occurs in humans. At the other end of the vertebrate spectrum, if crows have - if only partially – human-advanced cognitive abilities (Bugnyar, Reference Bugnyar2024; Güntürkün et al., Reference Güntürkün, Pusch and Rose2024) that in humans are related to consciousness (Güntürkün, Reference Güntürkün2021; Nieder, Reference Nieder2021) it is likely that their far-through evolved dorsal pallium can affect the “primary” brain in the same way as the human isocortex. By comparing the modulation observed in humans with that in birds, it may be possible to distinguish specific cortical influences via forebrain networks from non-specific influences. This is indeed an interesting thought that is worth investigating further.

Acknowledgements

This article was able to emerge thanks to years of cooperation and many fruitful discussions with Prof. Svetlana A. Ivanova and her colleagues of the Mental Health Research Institute, Tomsk National Research Medical Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 634014 Tomsk, Russia. The figures by Stella Simons are in the public domain and can be freely downloaded from the Prof. Dr Anton J.M. Loonen Foundation site (www.antonloonen.nl).

Financial support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Funding Statement

Open access funding provided by University of Groningen.

Competing interests

none

Statement

During the preparation of this work the author used DeepL Translate (https://www.deepl.com/nl/translator) in order to increase variability of English language formulations. After using this tool/service, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.