Violence against women (VAW)Footnote 1 is a global problem, with one in three women experiencing physical or sexual violence at least once in their lifetime (WHO, 2021). With the share of women in politics steadily increasing around the world and VAW gaining political salience, it is critical to understand whether women politicians are more effective in reducing VAW.

At the legislative level, scholars have found no association between the number of women in legislatures and the implementation of comprehensive or progressive policies to combat VAW (Htun and Weldon, Reference Htun and Weldon2012; Beer, Reference Beer2017). However, at the sub-national level, some have found that women’s representation in local government can decrease deeply engendered attitudes and beliefs and shift their attitudes and behavior toward women and VAW (Beaman et al., Reference Beaman, Chattopadhyay, Duflo, Pande and Topalova2009; Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Mani, Mishra and Topalova2012; Kuipers, Reference Kuipers2020). Perhaps most relevant, a study in India found that women’s descriptive representation in local governments and as heads of local governments had no effect on the prevalence of VAW crimes but did increase the number of reported crimes against women, as well as arrests for these crimes (Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Mani, Mishra and Topalova2012). Related studies analyzing women executives and gendered policies have found that women leaders invest more in infrastructure that directly benefits women (Chattopadhyay and Duflo, Reference Chattopadhyay and Duflo2004), raise the educational attainment of girls (Beaman et al., Reference Beaman, Duflo, Pande and Topalova2012), increase spending on women’s issues (Funk and Philips, Reference Funk and Philips2019), and change the gender composition of bureaucracies (Albertiet al., Reference Alberti, Diaz-Rioseco and Visconti2022; Erlandsen et al., Reference Erlandsen, Hernández-Garza and Schulz2022). Thus, while the effect of women’s local political representation through executive positions on actual instances of VAW remains relatively unexplored, there is good reason to believe that women executives may impact these outcomes.Footnote 2

This short article provides an initial empirical evaluation of this issue through an analysis of women mayors and VAW in Mexico. The article uses a pre-registered regression discontinuity design (RDD) leveraging close elections where women mayors narrowly defeat men candidates to assess whether women-led municipalities have systematically different VAW outcomes than those led by men.Footnote 3 Drawing on data from the 2018 local elections in Mexico for 1,476 municipalities and VAW outcomes during the 3 years of the mayoral term that followed (2019–21), we find that municipalities with women mayors have 3.84 fewer homicides of women and 2.36 fewer homicides of young women over the course of the 3-year term. We also probe possible mechanisms and find that women mayors make explicit efforts to combat VAW, have more women staff and women-led municipal institutions, and provide more specialized services and care for crime victims through public security institutions.

1. Background and data

We focus on Mexico, where women’s political representation is high and VAW is prevalent and politically salient. Between 2015 and 2018, the proportion of women mayors nearly doubled, from 14 to 26% (ONU Mujeres, 2018). Yet, recent reports show that over 70% of Mexican women suffer from violence at least once in their lives (INEGI, 2021), and an average of 10 women are murdered every day (OECD, 2017). VAW has become a key political and electoral topic (Arista, Reference Arista2022) and since the early 2000s, Mexican national and subnational governments have created numerous institutions specifically to address women’s issues and prevent gender-based violence.Footnote 4

Mexico has 2,454 municipalities governed by an elected mayor (presidente municipal) who oversees the municipal council (ayuntamiento). Mayors are elected by plurality vote and serve for 3 years. Municipal elections primarily occur in July and mayors take office near the end of election year. We focus on the effect of mayors on VAW because they tend to have closer links with citizens, are better able to respond to local issues, and have considerable de jure and de facto powers given Mexico’s federal system (Selee, Reference Selee2011), including oversight of municipal institutions, public programs, and law enforcement, which can affect the prevalence of VAW.

To determine the effect of women mayors on VAW in Mexico, we create a dataset covering 1,476 local elections in 2018 across 23 statesFootnote 5 and VAW data during the 3 years of the mayoral administration (2019–2021). Using data from each state’s electoral agency, we hand-code the gender of the first and second place candidates and calculate the difference in the share of votes received by the top two candidates. Of the 1,476 municipalities analyzed, 611 (41.4%) held elections where a woman and a man were the top two vote-receiving candidates.

We analyze the effect of women mayors on various forms of VAW for the 2018 mayoral administration. We explore these outcomes disaggregated by term year to analyze temporal effects and pooled (total instances) to examine overall effects. Using official death certificate data from Mexico’s Statistical Agency (INEGI), we calculate the total number of women in each municipality who died by homicide each year. We also construct a measure of homicides of young women aged 15–44, as this group is particularly vulnerable to VAW in Mexico (SEGOB, INMUJERES, and ONU Mujeres, 2017) and Latin America (ECLAC, 2021). To measure other forms of VAW, we use official data from the National Security Agency (SESNSP) on instances of reported rape, domestic violence, sexual abuse, and sexual harassment from 2019 to 2021. One limitation is that these reported crimes are not disaggregated by victim gender. However, since 90% of sexual violence victims are women both in Mexico (Universal, Reference Universal2019) and worldwide (UN Women, 2022), we believe that these data are a valid measure of our proposed concept. Moreover, if any reporting bias is present, measures drawn from crime report data should understate the prevalence of VAW, leading our estimate of the treatment effect to be more conservative (Jaitman and Anauati, Reference Jaitman and Anauati2019).

2. Research design

To estimate the effect women politicians have on VAW, we leverage an RDD of close elections. Our research design exploits close mayoral races in 2018 where either (1) a woman candidate narrowly defeats a man candidate or (2) a man candidate narrowly defeats a woman candidate, (n = 611). The close election RDD allows us to leverage the election of a woman to estimate the local average treatment effect of having a woman mayor on VAW. If the continuity assumption is met, municipalities where a woman narrowly defeated a man should serve as a good counterfactual for municipalities where a man narrowly defeated a woman (De la Cuesta and Imai, Reference De la Cuesta and Imai2016).

Formally, we estimate the following specification:

where Yi denotes the number of instances of a particular VAW outcome in municipality i; Wi is a binary variable that takes the value of 1 if a woman was elected mayor in municipality i and 0 otherwise; the running variable Xi is the margin of victory which takes positive values when a woman candidate wins and negative values when a man candidate wins; and ![]() $f(X_i)$ is a polynomial that denotes the functional form used to estimate the model. The coefficient of interest is τ, which estimates the causal effect of having a woman mayor on outcome Yi.

$f(X_i)$ is a polynomial that denotes the functional form used to estimate the model. The coefficient of interest is τ, which estimates the causal effect of having a woman mayor on outcome Yi.

Following the literature, we estimate first- and second-order polynomials (Calonico et al., Reference Sebastian, Cattaneo and Titiunik2014; Gelman and Imbens, Reference Gelman and Imbens2019) using optimal bandwidths that minimize the mean-squared error (MSE) (Calonico et al., Reference Sebastian, Cattaneo and Titiunik2014) and robust standard errors. The RDD is estimated using a triangular kernel. We rely on the rdrobust package in R to estimate the RDD (Calonico et al., Reference Sebastian, Cattaneo and Titiunik2015).

2.1. Identification and threats to inference

We run a series of tests to evaluate the robustness of the main results and include details in the Appendix. First, the key assumption of the RDD is that potential outcomes are continuously distributed at the treatment cutoff; that is, the only change at the cutoff is the treatment status (De la Cuesta and Imai, Reference De la Cuesta and Imai2016). This assumption could be violated if candidates can influence their assignment-to-treatment (the margin of victory) and sort nonrandomly around the threshold. We conduct the McCrary test (McCrary, Reference McCrary2008) and a nonparametric test (Cattaneo et al., Reference Cattaneo, Jansson and Ma2020) and find no evidence of sorting. Discontinuities in confounding variables at the threshold could also violate the identification assumption. We conduct balance tests by estimating the RDD using municipal-level gender sociodemographic data from the 2010 Census as outcomes—e.g., number of women, economically active women, women-run households, and average women’s education. We find no discontinuity at the threshold, suggesting that the findings are not driven by underlying gendered differences across municipalities.

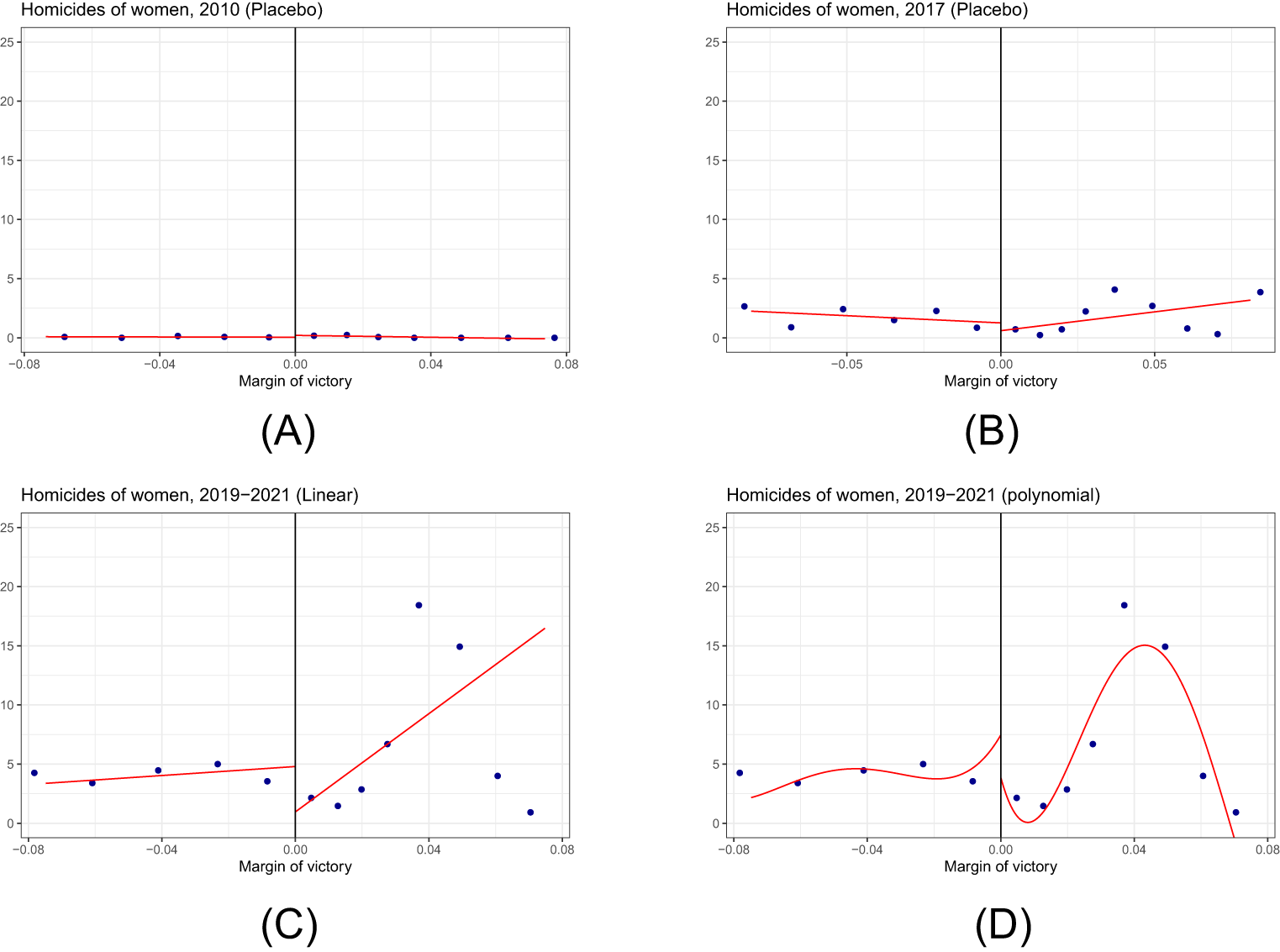

Additionally, we conduct two placebo tests by using past VAW outcomes: homicides of women and young women in 2010, to align with the sociodemographic Census data, and in 2017, to capture VAW outcomes before the election (Figure 1, Plots A and B). Null results in both tests provide compelling evidence that women politicians did not self-select into and win close elections in municipalities with low VAW levels. There is also no evidence of a spurious correlation due to some confounding municipal characteristic driving both low VAW levels and the electoral success of women politicians in close elections.

Figure 1. Linear RDD plots for (A) homicides of women in 2010 (placebo), (B) homicides of women in 2017 (placebo), (C) homicides of women from 2019 to 2021, and polynomial RDD plot for (D) homicides of women from 2019 to 2021. Running variable is winning margin. Bandwidths are optimized to minimize the mean-squared error. Data is binned using spacing estimators. rdplot in R is used to plot the RDDs.

To ensure the robustness of our main models, we also conduct placebo cutoff tests, use alternative bandwidths, higher-order polynomials, and an alternative estimation strategy—local randomization (see Appendix). The sample size could explain why some estimates are not statistically significant. Following Lucardi et al. Reference Lucardi, Micozzi and Vallejo(2023), the main table includes the power to detect an effect of one standard deviation (SD) of the outcome for the untreated group for each specification (Cattaneo et al., Reference Cattaneo, Titiunik and Vazquez-Bare2019).

Even with district-level balance, our RDD could be capturing both the gender effect and compensating differentials (Marshall, Reference Marshall2024), affecting interpretation of results. The direction of the potential bias is unclear. Unfortunately, there is no data on candidate characteristics to bound the effect, but we test whether women mayors disproportionately come from major parties or benefit from political alignment. We find no differences in partisanship but do find that women mayors benefit more from political alignment (see Appendix). Given the null results for non-VAW crimes, if political alignment is aiding women mayors it appears to do so only for VAW and homicides. Moreover, the main effects of women mayors on VAW become slightly larger when controlling for party or alignment, showing that these factors do not explain the results. The RDD estimates should nevertheless be interpreted as capturing the (weighted) effects of gender and possible compensating differentials.

3. Results

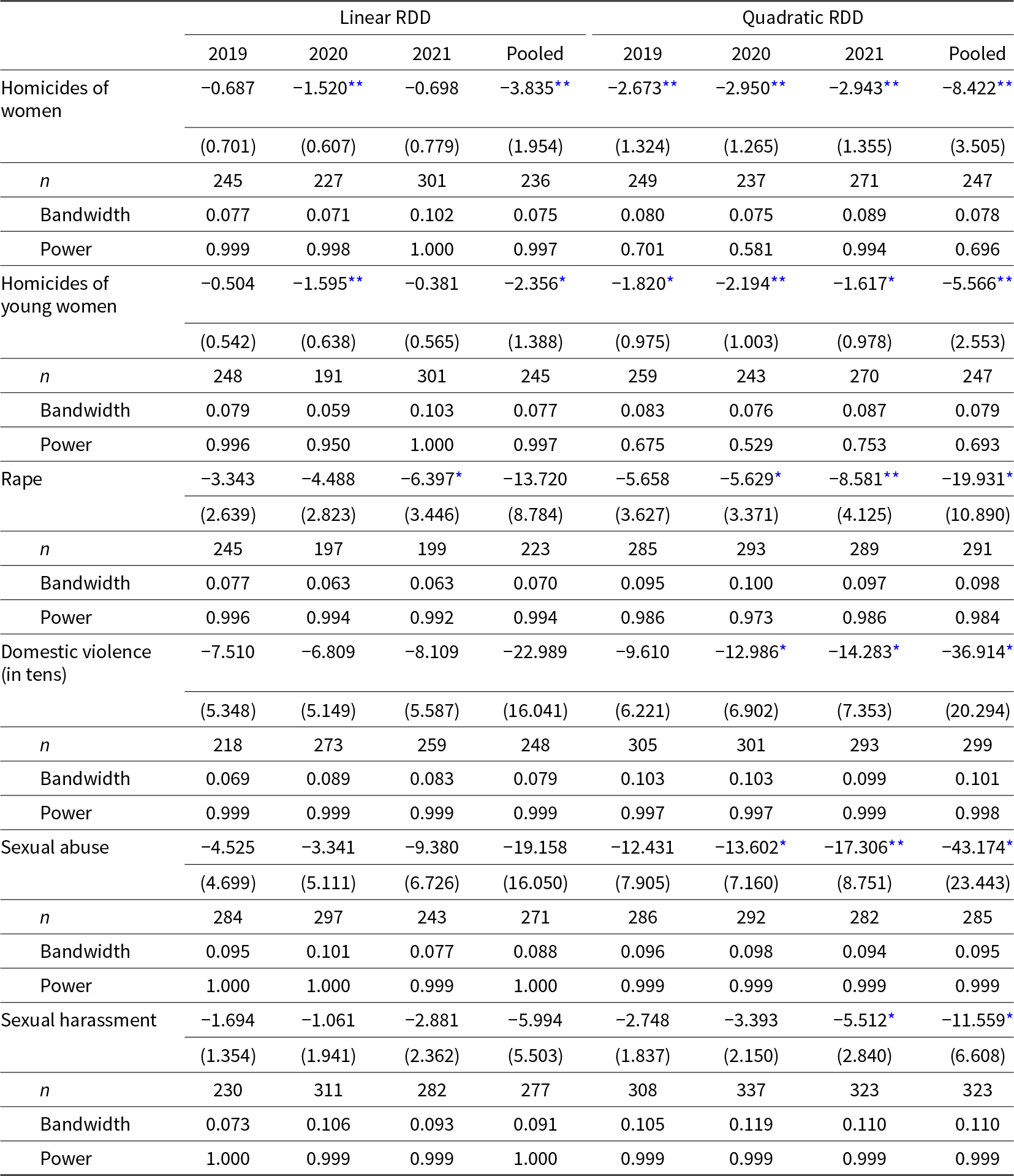

Table 1 presents the main RDD estimates for VAW outcomes across a mayor’s 3-year term (2019–2021) and pooled results. We report linear specifications for all years and second-order polynomial estimates for the pooled model. Higher-order polynomials are consistent with the quadratic model.

Table 1. Regression discontinuity results: Effect of women politicians on VAW

Notes: Conventional RDD estimates with robust standard errors and optimal bandwidth that minimizes mean-squared errors. Robust standard errors shown in parentheses.

* p < 0.1, **p < 0.05.

We find strong evidence that women politicians reduce the most severe forms of VAW, including homicides of women and young women, and reports of rape. We find suggestive evidence that they reduce other forms of VAW like domestic violence, sexual abuse, and sexual harassment. Specifically, the more conservative linear RDD point estimates find that during their 3-year terms, women mayors reduce homicides of women by 0.458 SDs (SD = 8.379 among observations within the MSE optimal bandwidth, to the left of the cutoff), and homicides of young women by 0.395 SDs (SD = 5.960 among observations within the MSE optimal bandwidth, to the left of the cutoff). These effects are substantively large and suggest that women-led municipalities have 3.84 fewer homicides of women (a 64.7% decline) and 2.36 fewer homicides of young women (57.1% decline) over a 3-year period.

For other VAW-related crimes, all linear and quadratic RDD point estimates are negative. Results from both RDD specifications indicate that women politicians significantly reduce rape their third year in office (p < 0.1 in linear models; p < 0.05 in quadratic models) and that they generally have a more discernible impact on non-homicide VAW outcomes the longer they are in office. The estimates from the quadratic RDD indicate that women mayors systematically reduce instances of domestic violence, sexual abuse, and sexual harassment by their third year in office and overall during their term (p < 0.1). Since data on non-homicide VAW come from reported crimes, these results could reflect a reduction in VAW reporting, rather than VAW prevalence. However, we believe our findings are unlikely to be caused by a negative reporting effect for three reasons: (1) our results using death certificate data show that women mayors reduce actual homicides of women; (2) we show women mayors do not reduce reporting of non-VAW crimes (see below); and (3) previous research shows that women politicians increase VAW reporting (Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Mani, Mishra and Topalova2012).

3.1. Probing mechanisms

Mayors may influence VAW through several channels (see

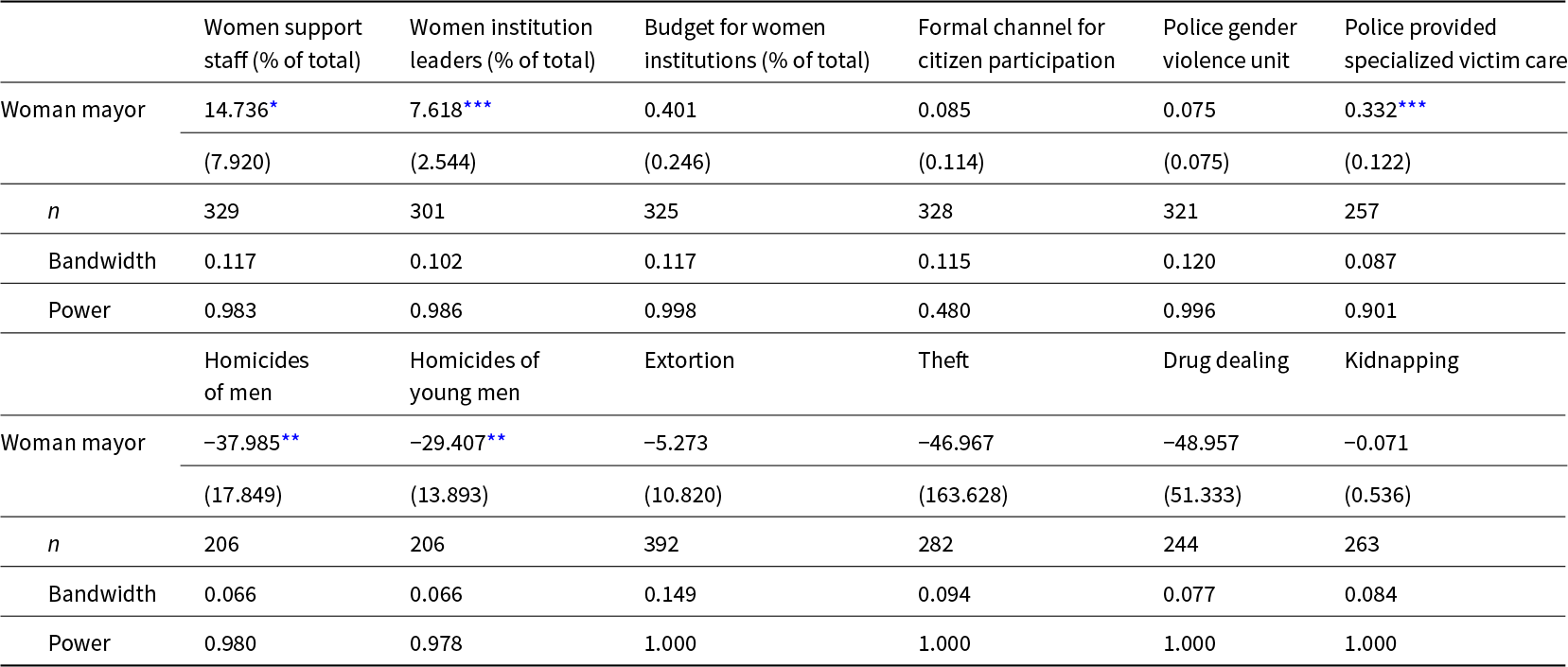

INMUJERES, 2005; 2022). Qualitatively investigating a subset of narrowly elected women mayors (![]() $0 \leq X_{i}\leq0.2$%, n = 33), we find that most spearheaded initiatives to combat VAW (detailed in the Appendix), including leveraging municipal institutions to provide programs, workshops, events, and services. To assess the systematic effects of these efforts, we estimate the RDD using official 2020 municipal government data (the only year these data are available). Table 2 shows that women mayors have more women staff and women-led municipal institutions, likely improving institutional awareness and responsiveness to gendered violence. They are also more likely to have municipal police offering specialized services and care for victims and, though not statistically significant, specialized units addressing VAW, which may reduce barriers to reporting and enhance response measures. Additional results, though not statistically significant, suggest that women mayors spend more on institutions addressing women’s issues and establish more channels for citizen participation, enabling sustained efforts to combat VAW. Together, these mechanisms suggest that women mayors influence VAW by institutionalizing gender-responsive policies and fostering environments where VAW is less likely to persist.

$0 \leq X_{i}\leq0.2$%, n = 33), we find that most spearheaded initiatives to combat VAW (detailed in the Appendix), including leveraging municipal institutions to provide programs, workshops, events, and services. To assess the systematic effects of these efforts, we estimate the RDD using official 2020 municipal government data (the only year these data are available). Table 2 shows that women mayors have more women staff and women-led municipal institutions, likely improving institutional awareness and responsiveness to gendered violence. They are also more likely to have municipal police offering specialized services and care for victims and, though not statistically significant, specialized units addressing VAW, which may reduce barriers to reporting and enhance response measures. Additional results, though not statistically significant, suggest that women mayors spend more on institutions addressing women’s issues and establish more channels for citizen participation, enabling sustained efforts to combat VAW. Together, these mechanisms suggest that women mayors influence VAW by institutionalizing gender-responsive policies and fostering environments where VAW is less likely to persist.

Table 2. Linear RDD results: Effect of women politicians on administrative outcomes (2020) and non-VAW crimes (2019–2021)

Notes: Conventional RDD estimates with robust standard errors and optimal bandwidth that minimizes mean-squared errors.

* p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Lastly, it could be that women politicians address crime more broadly rather than just VAW. We estimate the RDD using the following outcomes: homicides of men and young men, extortion, home burglary and vehicle theft, kidnapping, and drug dealing. Table 2 shows that for the pooled sample, women mayors also reduced homicides of men and young men. Interestingly, while coefficients for homicides of (young) women are largest during their second year in office, those for (young) men are strongest the third year and weakest the second (see Appendix). Additionally, women politicians have no effect on the prevalence of reported non-VAW crimes for any year or the full term, suggesting that women mayors reduce VAW and homicides more broadly but do not differentially impact non-VAW crimes.

4. Concluding remarks

We find that women mayors reduce homicides of women and some reported instances of VAW relative to men mayors. We provide qualitative evidence that women mayors actively spearheaded anti-VAW initiatives and suggestive quantitative evidence that they appoint more women to local governments and provide more services to victims. However, these results are limited to contemporary Mexico and further research should be conducted in other contexts. Nevertheless, the findings highlight the importance of women’s representation in local politics in advancing women’s safety.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2025.10030. To obtain replication material for this article, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/1KEFJ5.

Acknowledgements

We thank Claire Adida, Sebastian Saiegh, Austin Beacham, and two anonymous reviewers for their comments. We also thank Natalie Arce and Olina Philippoussis for their research assistance.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

None.