1. Introduction

Understanding the physics of droplet impact on a solid wall is an important practical problem, as well as being a source of scientific curiosity. Practical applications include inkjet printing (Yarin Reference Yarin2006), cooling (Yarin Reference Yarin2006; Sáenz et al. Reference Sáenz, Sefiane, Kim, Matar and Valluri2015) and crop spraying (Yarin Reference Yarin2006; Moghtadernejad, Lee & Jadidi Reference Moghtadernejad, Lee and Jadidi2020), while droplet impact on superhydrophobic surfaces has important de-icing applications in aviation and in power transmission (Khojasteh et al. Reference Khojasteh, Kazerooni, Salarian and Kamali2016). Droplet impact has been studied using experimental (Chandra & Avedisian Reference Chandra and Avedisian1991; Antonini, Amirfazli & Marengo Reference Antonini, Amirfazli and Marengo2012; Riboux & Gordillo Reference Riboux and Gordillo2014), theoretical (Roisman, Rioboo & Tropea Reference Roisman, Rioboo and Tropea2002; Gordillo, Riboux & Quintero Reference Gordillo, Riboux and Quintero2019) and computational (Fukai, Tanaka & Miyatake Reference Fukai, Tanaka and Miyatake1998; Gunjal, Ranade & Chaudhari Reference Gunjal, Ranade and Chaudhari2005; Eggers et al. Reference Eggers, Fontelos, Josserand and Zaleski2010) methods. The various impact regimes have been categorised as involving bounce, deposition or splash (Josserand & Thoroddsen Reference Josserand and Thoroddsen2016). Droplet splash can be further categorised as either prompt splash or corona splash. Bouncing and deposition depend on the wetting properties of the substrate. The regime which occurs also depends crucially on droplet’s Weber number (

![]() ${\textit{We}}$

) and Reynolds number (

${\textit{We}}$

) and Reynolds number (

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

). For consistency with previous work (but going back to Eggers et al. (Reference Eggers, Fontelos, Josserand and Zaleski2010)), we use the definitions

${\textit{Re}}$

). For consistency with previous work (but going back to Eggers et al. (Reference Eggers, Fontelos, Josserand and Zaleski2010)), we use the definitions

where

![]() $\rho$

is the liquid density,

$\rho$

is the liquid density,

![]() $\mu$

is the liquid dynamic viscosity and

$\mu$

is the liquid dynamic viscosity and

![]() $\gamma$

is the surface tension. Also,

$\gamma$

is the surface tension. Also,

![]() $U_0$

is the droplet’s speed prior to impact and

$U_0$

is the droplet’s speed prior to impact and

![]() $R_0$

is the droplet radius prior to impact.

$R_0$

is the droplet radius prior to impact.

In this context, there is a splash parameter

![]() $K={\textit{We}}\sqrt {{\textit{Re}}}$

, which determines a threshold above which splash occurs (Mundo, Sommerfeld & Tropea Reference Mundo, Sommerfeld and Tropea1995). The threshold value is not universal (Marengo et al. Reference Marengo, Antonini, Roisman and Tropea2011), and different experiments have produced different values, a summary of which is provided in Moreira, Moita & Panao (Reference Moreira, Moita and Panao2010). The review by Josserand & Thoroddsen (Reference Josserand and Thoroddsen2016) states that ‘for impacts at

$K={\textit{We}}\sqrt {{\textit{Re}}}$

, which determines a threshold above which splash occurs (Mundo, Sommerfeld & Tropea Reference Mundo, Sommerfeld and Tropea1995). The threshold value is not universal (Marengo et al. Reference Marengo, Antonini, Roisman and Tropea2011), and different experiments have produced different values, a summary of which is provided in Moreira, Moita & Panao (Reference Moreira, Moita and Panao2010). The review by Josserand & Thoroddsen (Reference Josserand and Thoroddsen2016) states that ‘for impacts at

![]() $K$

exceeding

$K$

exceeding

![]() ${\sim}3000$

one can expect a splash’. Riboux & Gordillo (Reference Riboux and Gordillo2014) have recast the splash threshold in terms of powers of

${\sim}3000$

one can expect a splash’. Riboux & Gordillo (Reference Riboux and Gordillo2014) have recast the splash threshold in terms of powers of

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

,

${\textit{Re}}$

,

![]() ${Oh}=\sqrt {\textit{We}}/{\textit{Re}}$

, and the gas–liquid viscosity ratio. The authors find good agreement between their theoretical model and experiments. Just below the splash threshold, and typically for

${Oh}=\sqrt {\textit{We}}/{\textit{Re}}$

, and the gas–liquid viscosity ratio. The authors find good agreement between their theoretical model and experiments. Just below the splash threshold, and typically for

![]() ${\textit{We}} \geq 10^2$

and

${\textit{We}} \geq 10^2$

and

![]() ${\textit{Re}} \geq 10^3$

(de Ruiter et al. Reference de, Jolet, Rachel and Stone2010), there is a ‘rim-lamella’ (RL) regime, in which the droplet flattens and spreads into an axisymmetric structure involving a lamella, with a thicker rim forming at the extremity. A key parameter which characterises the droplet impact in this regime is the maximum spreading radius, denoted here by

${\textit{Re}} \geq 10^3$

(de Ruiter et al. Reference de, Jolet, Rachel and Stone2010), there is a ‘rim-lamella’ (RL) regime, in which the droplet flattens and spreads into an axisymmetric structure involving a lamella, with a thicker rim forming at the extremity. A key parameter which characterises the droplet impact in this regime is the maximum spreading radius, denoted here by

![]() $\mathcal{R}_{\textit{max}}$

, and is governed by

$\mathcal{R}_{\textit{max}}$

, and is governed by

![]() ${\textit{We}}$

and

${\textit{We}}$

and

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

. This quantity has applications in inkjet printing and forensic science (Josserand & Thoroddsen Reference Josserand and Thoroddsen2016). Even in this deposition regime, the presence of azimuthal instabilities which do not lead to topological transitions has been noted (Huang, Wan & Taslim Reference Huang, Wan and Taslim2018).

${\textit{Re}}$

. This quantity has applications in inkjet printing and forensic science (Josserand & Thoroddsen Reference Josserand and Thoroddsen2016). Even in this deposition regime, the presence of azimuthal instabilities which do not lead to topological transitions has been noted (Huang, Wan & Taslim Reference Huang, Wan and Taslim2018).

Certainly, droplet spreading is a three-dimensional phenomenon, exhibiting axisymmetry below the splash threshold. However, this paper focuses instead on cylindrical (quasi-two-dimensional) droplet impacts. Cylindrical droplets are unstable to the Rayleigh–Plateau instability, and cannot exist naturally over time scales greater than a characteristic breakup time

![]() $t_{\textit{breakup}}\sim [\rho R_0^3/\gamma ]^{1/2}$

(

$t_{\textit{breakup}}\sim [\rho R_0^3/\gamma ]^{1/2}$

(

![]() ${\lt}4\,\mathrm{ms}$

for a

${\lt}4\,\mathrm{ms}$

for a

![]() $1\,\mathrm{mm}$

-radius cylinder of water in air) (Chandrasekhar Reference Chandrasekhar1981). However, the present study may be indirectly applicable in certain experimental works, a summary of which is presented below.

$1\,\mathrm{mm}$

-radius cylinder of water in air) (Chandrasekhar Reference Chandrasekhar1981). However, the present study may be indirectly applicable in certain experimental works, a summary of which is presented below.

We mention in particular the paper by Néel et al. (Reference Néel, Lhuissier and Villermaux2020). There, the authors pierce a liquid sheet in two separate places, to form two holes in the sheet. The holes retract along their respective rims, with each rim rolling up into a toroidal shape. Arguably, the process is better described using a schematic diagram, which, for the purpose of maintaining focus in the introduction, is relegated to Appendix A. As the holes expand, their rims (the tori) approach one another and eventually collide. The minor radius of each torus is small compared with the size of the collision zone, meaning the collision is similar to a head-on collision of two liquid cylinders. The maximum spreading of the impacting tori scales as

![]() $\mathcal{R}_{\textit{max}}\sim {\textit{We}}$

, which we demonstrate below using the RL model to be a fundamentally two-dimensional (2-D) scaling behaviour.

$\mathcal{R}_{\textit{max}}\sim {\textit{We}}$

, which we demonstrate below using the RL model to be a fundamentally two-dimensional (2-D) scaling behaviour.

We mention also the work by Camus (Reference Camus1971), in which a cylindrical liquid droplet is generated by confining a liquid bridge between two parallel plates. Impact is achieved by projecting a third plate between the two spaced plates. Images of the resulting quasi-2-D droplet impacts are reproduced in the work by Field, Lesser & Dear (Reference Field, Lesser and Dear1985). This configuration enables precise observation of the internal dynamics (e.g. via schlieren imaging), while avoiding the refraction problems inherent in studies of spherical droplets (Field et al. Reference Field, Lesser and Dear1985). Although the work of Camus involves extremely high impact speeds (up to

![]() $70\,\mathrm{m}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}$

) where compressibility effects are important, it does show how quasi-2-D impacts are realisable in the laboratory and are therefore a worthwhile subject for theoretical modelling.

$70\,\mathrm{m}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}$

) where compressibility effects are important, it does show how quasi-2-D impacts are realisable in the laboratory and are therefore a worthwhile subject for theoretical modelling.

The same basic method of creating quasi-2-D droplets has been applied by Kärki et al. (Reference Kärki, Pääkkönen, Kyriakopoulos and Timonen2024). The paper also contains some investigations of droplet impact in two dimensions, albeit at very low impact speeds with

![]() ${\textit{We}}\ll 1$

– the opposite extreme to Camus (Reference Camus1971). Therefore, the present work addresses (albeit only theoretically) a missing regime not covered by the experiments. This observation comes with the caveat that the investigated quasi-2-D droplets are sustained between two plates, and thus, the presented model can only ever provide a partial representation of these experiments.

${\textit{We}}\ll 1$

– the opposite extreme to Camus (Reference Camus1971). Therefore, the present work addresses (albeit only theoretically) a missing regime not covered by the experiments. This observation comes with the caveat that the investigated quasi-2-D droplets are sustained between two plates, and thus, the presented model can only ever provide a partial representation of these experiments.

A further motivation for the study of 2-D RL models is to shed light on computational works. We mention the work by Tang, Adcock & Mostert (Reference Tang, Adcock and Mostert2024), in which the authors simulate the head-on collision of two liquid cylinders (equivalent to the impact of a liquid cylinder on a free-slip surface with contact angle

![]() $90^\circ$

). These simulations are performed in a full three-dimensional (3-D) geometry, and fingering is observed post collision, corresponding to an impact scenario above an effective splash threshold (e.g. figure 11

b). To understand the simulation results in depth, the authors introduce a 2-D RL model for the head-on collision of the two liquid cylinders. This particular model is a special case of the model in the present work. The theoretical bounds obtained herein can therefore be used to understand the scaling behaviour (with

$90^\circ$

). These simulations are performed in a full three-dimensional (3-D) geometry, and fingering is observed post collision, corresponding to an impact scenario above an effective splash threshold (e.g. figure 11

b). To understand the simulation results in depth, the authors introduce a 2-D RL model for the head-on collision of the two liquid cylinders. This particular model is a special case of the model in the present work. The theoretical bounds obtained herein can therefore be used to understand the scaling behaviour (with

![]() ${\textit{We}}$

) of this particular collision set-up. Appropriate schematic diagrams depicting both the experiment of Kärki et al. (Reference Kärki, Pääkkönen, Kyriakopoulos and Timonen2024) and the simulations of Tang et al. (Reference Tang, Adcock and Mostert2024) are provided in Appendix A.

${\textit{We}}$

) of this particular collision set-up. Appropriate schematic diagrams depicting both the experiment of Kärki et al. (Reference Kärki, Pääkkönen, Kyriakopoulos and Timonen2024) and the simulations of Tang et al. (Reference Tang, Adcock and Mostert2024) are provided in Appendix A.

We mention finally the wide range of previous computational studies on 2-D droplet impact, for instance Ding, Spelt & Shu (Reference Ding, Spelt and Shu2007), Shin & Juric (Reference Shin and Juric2009), Gupta & Kumar (Reference Gupta and Kumar2011), Wu & Cao (Reference Wu and Cao2017), Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Gui, Yang, Tu and Jiang2021) and Rafi, Haque & Ahmed (Reference Rafi, Haque and Ahmed2022). By providing a rigorous method to estimate the spreading radius, the present theoretical analysis provides insights into these studies.

In Ó Náraigh & Mairal (Reference Ó Náraigh and Mairal2023), a 2-D energy-budget analysis of droplet impact is proposed. This allows one to estimate the maximum spreading radius, written in dimensionless terms as

![]() $\beta _{\textit{max}}=\mathcal{R}_{\textit{max}}/R_0$

. By balancing the energy before impact and at maximum spreading, the following correlation is obtained:

$\beta _{\textit{max}}=\mathcal{R}_{\textit{max}}/R_0$

. By balancing the energy before impact and at maximum spreading, the following correlation is obtained:

\begin{align} \underbrace {1}_{{\overset {\text{Pre-impact}}{\scriptscriptstyle \text{kinetic energy}}}}+\underbrace {\frac {4}{\textit{We}}}_{\overset {\text{Pre-impact}}{\scriptscriptstyle \text{surface energy}}} &= \underbrace {\frac {2}{\pi {\textit{We}}}\left [2\beta _{\textit{max}}\left (1-\cos \vartheta \right )+ \frac {\pi }{\beta _{\textit{max}}}\right ]}_{\overset {\text{Surface energy}}{\scriptscriptstyle \text{at maximum spreading}}} \nonumber \\&\quad +\underbrace {\frac {2}{\pi }\frac {2a}{\sqrt {{\textit{Re}}}}\beta _{\textit{max}}\sqrt {\beta _{\textit{max}}-1}}_{\overset {\text{Viscous dissipation}}{\scriptscriptstyle \text{in the boundary layer}}}+\underbrace {b}_{\text{Head loss}} \! . \end{align}

\begin{align} \underbrace {1}_{{\overset {\text{Pre-impact}}{\scriptscriptstyle \text{kinetic energy}}}}+\underbrace {\frac {4}{\textit{We}}}_{\overset {\text{Pre-impact}}{\scriptscriptstyle \text{surface energy}}} &= \underbrace {\frac {2}{\pi {\textit{We}}}\left [2\beta _{\textit{max}}\left (1-\cos \vartheta \right )+ \frac {\pi }{\beta _{\textit{max}}}\right ]}_{\overset {\text{Surface energy}}{\scriptscriptstyle \text{at maximum spreading}}} \nonumber \\&\quad +\underbrace {\frac {2}{\pi }\frac {2a}{\sqrt {{\textit{Re}}}}\beta _{\textit{max}}\sqrt {\beta _{\textit{max}}-1}}_{\overset {\text{Viscous dissipation}}{\scriptscriptstyle \text{in the boundary layer}}}+\underbrace {b}_{\text{Head loss}} \! . \end{align}

Hence, (1.2) is an energy balance made dimensionless on the kinetic energy density

![]() $(1/2)\rho U_0^2$

. Also,

$(1/2)\rho U_0^2$

. Also,

![]() $\vartheta$

is an appropriate contact angle, usually taken to be the advancing contact angle (for a discussion on this, see Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Yang, Wang, Zhu and Fang2019)). The `head loss’ term in (1.2) is a key term which reflects energy dissipation due to internal flows which develop in the RL structure and which are otherwise not included in a simple energy balance. The head loss can be modelled as a simple fraction of the initial kinetic energy (Wildeman et al. Reference Wildeman, Visser, Sun and Lohse2016). A theoretical justification for this is given in Villermaux & Bossa (Reference Villermaux and Bossa2011). In this way, (1.2) contains two free parameters,

$\vartheta$

is an appropriate contact angle, usually taken to be the advancing contact angle (for a discussion on this, see Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Yang, Wang, Zhu and Fang2019)). The `head loss’ term in (1.2) is a key term which reflects energy dissipation due to internal flows which develop in the RL structure and which are otherwise not included in a simple energy balance. The head loss can be modelled as a simple fraction of the initial kinetic energy (Wildeman et al. Reference Wildeman, Visser, Sun and Lohse2016). A theoretical justification for this is given in Villermaux & Bossa (Reference Villermaux and Bossa2011). In this way, (1.2) contains two free parameters,

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() $b$

, which have been fitted to the data emanating from numerical simulations (Ó Náraigh & Mairal Reference Ó Náraigh and Mairal2023).

$b$

, which have been fitted to the data emanating from numerical simulations (Ó Náraigh & Mairal Reference Ó Náraigh and Mairal2023).

Equation (1.2) has some important asymptotic limits:

-

(i) inviscid limit: for

${\textit{Re}}\rightarrow \infty$

, (1.2) reduces to(1.3)with exact solution

${\textit{Re}}\rightarrow \infty$

, (1.2) reduces to(1.3)with exact solution \begin{align} \frac {\pi }{2}(1-b){\textit{We}}+2\pi =\left [2\beta _{\textit{max}}(1-\cos \vartheta )+\frac {\pi }{\beta _{\textit{max}}}\right ]\!, \end{align}

(1.4)For

\begin{align} \frac {\pi }{2}(1-b){\textit{We}}+2\pi =\left [2\beta _{\textit{max}}(1-\cos \vartheta )+\frac {\pi }{\beta _{\textit{max}}}\right ]\!, \end{align}

(1.4)For \begin{align} \beta _{\textit{max}}=\frac {\omega +\sqrt {\omega ^2-8\pi (1-\cos \vartheta )}}{4(1-\cos \vartheta )},\qquad \omega =\frac {\pi }{2}(1-b){\textit{We}}+2\pi . \end{align}

\begin{align} \beta _{\textit{max}}=\frac {\omega +\sqrt {\omega ^2-8\pi (1-\cos \vartheta )}}{4(1-\cos \vartheta )},\qquad \omega =\frac {\pi }{2}(1-b){\textit{We}}+2\pi . \end{align}

${\textit{We}}$

large but finite, this further reduces to(1.5)The equivalent scaling behaviour for 3-D axisymmetric droplets is (Wildeman et al. Reference Wildeman, Visser, Sun and Lohse2016)

${\textit{We}}$

large but finite, this further reduces to(1.5)The equivalent scaling behaviour for 3-D axisymmetric droplets is (Wildeman et al. Reference Wildeman, Visser, Sun and Lohse2016) \begin{align} \beta _{\textit{max}}\approx \frac {{\textit{We}}\,\pi (1-b)}{4(1-\cos \vartheta )}. \end{align}

(1.6)hence,

\begin{align} \beta _{\textit{max}}\approx \frac {{\textit{We}}\,\pi (1-b)}{4(1-\cos \vartheta )}. \end{align}

(1.6)hence, \begin{align} \beta _{\textit{max}}\approx \sqrt {\frac {4}{1-\cos \vartheta }\left [\dfrac {1}{12}(1-b){\textit{We}}+1\right ]}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \beta _{\textit{max}}\approx \sqrt {\frac {4}{1-\cos \vartheta }\left [\dfrac {1}{12}(1-b){\textit{We}}+1\right ]}, \end{align}

$\beta _{\textit{max}}\sim {\textit{We}}$

for 2-D Cartesian droplets and

$\beta _{\textit{max}}\sim {\textit{We}}$

for 2-D Cartesian droplets and

$\beta _{\textit{max}}\sim {\textit{We}}^{1/2}$

for 3-D axisymmetric droplets;

$\beta _{\textit{max}}\sim {\textit{We}}^{1/2}$

for 3-D axisymmetric droplets;

-

(ii) finite viscosity, large Weber number: for

${\textit{We}}\rightarrow \infty$

(1.2) reduces to(1.7)For

${\textit{We}}\rightarrow \infty$

(1.2) reduces to(1.7)For \begin{align} \frac {\pi }{2}(1-b)\approx \frac {2a}{\sqrt {{\textit{Re}}}}\beta _{\textit{max}}\sqrt {\beta _{\textit{max}}-1}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\pi }{2}(1-b)\approx \frac {2a}{\sqrt {{\textit{Re}}}}\beta _{\textit{max}}\sqrt {\beta _{\textit{max}}-1}. \end{align}

${\textit{Re}}$

large but finite, this gives

${\textit{Re}}$

large but finite, this gives

$\beta _{\textit{max}}\sim {\textit{Re}}^{1/3}$

for 2-D Cartesian droplets. The corresponding result for 3-D axisymmetric droplets is

$\beta _{\textit{max}}\sim {\textit{Re}}^{1/3}$

for 2-D Cartesian droplets. The corresponding result for 3-D axisymmetric droplets is

$\beta _{\textit{max}}\sim {\textit{Re}}^{1/5}$

.

$\beta _{\textit{max}}\sim {\textit{Re}}^{1/5}$

.

In the 3-D axisymmetric case, a RL model provides an alternative method for estimating the maximum spreading radius for 3-D axisymmetric droplets. The RL model is pertinent when the droplet spreads to form a RL structure (specifically,

![]() ${\textit{We}} \gtrsim 10^2$

,

${\textit{We}} \gtrsim 10^2$

,

![]() ${\textit{Re}} \gtrsim 10^3$

and below the splash threshold

${\textit{Re}} \gtrsim 10^3$

and below the splash threshold

![]() $K={\textit{We}}\sqrt {{\textit{Re}}}\lesssim 10^3-10^4$

). In a previous set of papers by Amirfazli et al. (Reference Amirfazli, Bustamante, Hu and Ó Náraigh2024) and Bustamante & Ó Náraigh (Reference Bustamante and Ó Náraigh2025), one of the present authors (with co-authors) was able to place rigorous bounds on the maximum spreading radius for 3-D axisymmetric droplets ((1.3), Bustamante & Ó Náraigh (Reference Bustamante and Ó Náraigh2025)). The bounds were derived by first formulating a RL model and then analysing the resulting set of ordinary differential equations using differential inequalities, in particular, Gronwall’s inequality (Doering & Gibbon Reference Doering and Gibbon1995). The bounds are found to be consistent with the correlation given by Roisman (Reference Roisman2009), stated here for a Reynolds number and a Weber number based on droplet radius (not diameter)

$K={\textit{We}}\sqrt {{\textit{Re}}}\lesssim 10^3-10^4$

). In a previous set of papers by Amirfazli et al. (Reference Amirfazli, Bustamante, Hu and Ó Náraigh2024) and Bustamante & Ó Náraigh (Reference Bustamante and Ó Náraigh2025), one of the present authors (with co-authors) was able to place rigorous bounds on the maximum spreading radius for 3-D axisymmetric droplets ((1.3), Bustamante & Ó Náraigh (Reference Bustamante and Ó Náraigh2025)). The bounds were derived by first formulating a RL model and then analysing the resulting set of ordinary differential equations using differential inequalities, in particular, Gronwall’s inequality (Doering & Gibbon Reference Doering and Gibbon1995). The bounds are found to be consistent with the correlation given by Roisman (Reference Roisman2009), stated here for a Reynolds number and a Weber number based on droplet radius (not diameter)

The correlation (1.8) has been validated extensively via numerical simulation (Wildeman et al. Reference Wildeman, Visser, Sun and Lohse2016) and experimental measurements. For completeness, we mention also the correlation due to Laan et al. (Reference Laan, De, Karla, Bartolo, Josserand and Bonn2014), which gives

a relationship also used in bloodstain pattern analysis (Laan et al. Reference Laan, de, Karla, Slenter, Wilhelm, Jermy and Bonn2015). Here,

![]() $P={\textit{WeRe}}^{-2/5}$

and

$P={\textit{WeRe}}^{-2/5}$

and

![]() $a_0$

and

$a_0$

and

![]() $a_1$

are empirical coefficients. Equation (1.9) reverts to (1.8) in the limit of large

$a_1$

are empirical coefficients. Equation (1.9) reverts to (1.8) in the limit of large

![]() $P$

. Such correlations have now been identified as limiting regimes within a unified framework by Sanjay & Lohse (Reference Sanjay and Lohse2025), while the effect of non-Newtonian rheology on the correlation has also been quantified by Mobaseri, Kumar & Cheng (Reference Mobaseri, Kumar and Cheng2025). Hence, based on the theory of Sanjay & Lohse (Reference Sanjay and Lohse2025), (1.8) is valid below the splash threshold at large

$P$

. Such correlations have now been identified as limiting regimes within a unified framework by Sanjay & Lohse (Reference Sanjay and Lohse2025), while the effect of non-Newtonian rheology on the correlation has also been quantified by Mobaseri, Kumar & Cheng (Reference Mobaseri, Kumar and Cheng2025). Hence, based on the theory of Sanjay & Lohse (Reference Sanjay and Lohse2025), (1.8) is valid below the splash threshold at large

![]() $P$

and low

$P$

and low

![]() $\textit{Oh}$

.

$\textit{Oh}$

.

1.1. Aim of the paper

The main aim of the present work is to establish a result analogous to (1.8) for 2-D droplets. For this purpose, we formulate a RL model for 2-D droplets. Within the framework of the RL model, we show

where

![]() $k_1$

and

$k_1$

and

![]() $k_2$

are constants to be determined, and

$k_2$

are constants to be determined, and

![]() $\vartheta _a$

is the advancing contact angle. We verify the bounds (1.10) using computational fluid dynamics simulations of droplet impact. We use the volume of fluid (VOF) method to capture the interface and hence to model the multiphase flow.

$\vartheta _a$

is the advancing contact angle. We verify the bounds (1.10) using computational fluid dynamics simulations of droplet impact. We use the volume of fluid (VOF) method to capture the interface and hence to model the multiphase flow.

A key motivation for studying the 2-D case is that the RL model in two dimensions is much simpler than in three dimensions. This makes the analysis more tractable. As a by-product of this analysis, we find that the RL model in the 2-D inviscid case is exactly solvable in terms of polynomials and square roots. This enables us to obtain an analytical expression confirming the scaling behaviour

![]() $\beta _{\textit{max}}\sim {\textit{We}}$

.

$\beta _{\textit{max}}\sim {\textit{We}}$

.

1.2. Plan of the paper

In § 2 we derive the RL model from first principles. The result is a set of coupled ordinary differential equations for the rim area

![]() $V$

, the greatest extent of the lamella

$V$

, the greatest extent of the lamella

![]() $R$

and the lamella height

$R$

and the lamella height

![]() $h$

. In § 3 we examine the inviscid limit of the model, where we derive a closed-form expression for

$h$

. In § 3 we examine the inviscid limit of the model, where we derive a closed-form expression for

![]() $R(t)$

, the variation of

$R(t)$

, the variation of

![]() $R$

with respect to time. Crucially, we find a closed-form expression for the maximum value of

$R$

with respect to time. Crucially, we find a closed-form expression for the maximum value of

![]() $R(t)$

,

$R(t)$

,

![]() $R_{\textit{max}}$

and show that it scales linearly with Weber number, a result consistent with the energy-budget analysis (1.5). In § 4 we extend the analysis to the viscous case. In this case, an exact closed-form solution is not possible; however, we use an analysis of the RL model based on Gronwall’s inequality to establish the bounds (1.10). In § 5 we validate the bounds using numerical simulations of 2-D droplet impact within the framework of the VOF method. Discussion and concluding remarks are presented in § 6. We emphasise that, in this paper, we use the symbol

$R_{\textit{max}}$

and show that it scales linearly with Weber number, a result consistent with the energy-budget analysis (1.5). In § 4 we extend the analysis to the viscous case. In this case, an exact closed-form solution is not possible; however, we use an analysis of the RL model based on Gronwall’s inequality to establish the bounds (1.10). In § 5 we validate the bounds using numerical simulations of 2-D droplet impact within the framework of the VOF method. Discussion and concluding remarks are presented in § 6. We emphasise that, in this paper, we use the symbol

![]() $V$

for rim area, to emphasise the similarity of theoretical model with previous work on 3-D axisymmetric droplets, where

$V$

for rim area, to emphasise the similarity of theoretical model with previous work on 3-D axisymmetric droplets, where

![]() $V$

was used to denote a rim volume.

$V$

was used to denote a rim volume.

2. Mathematical model

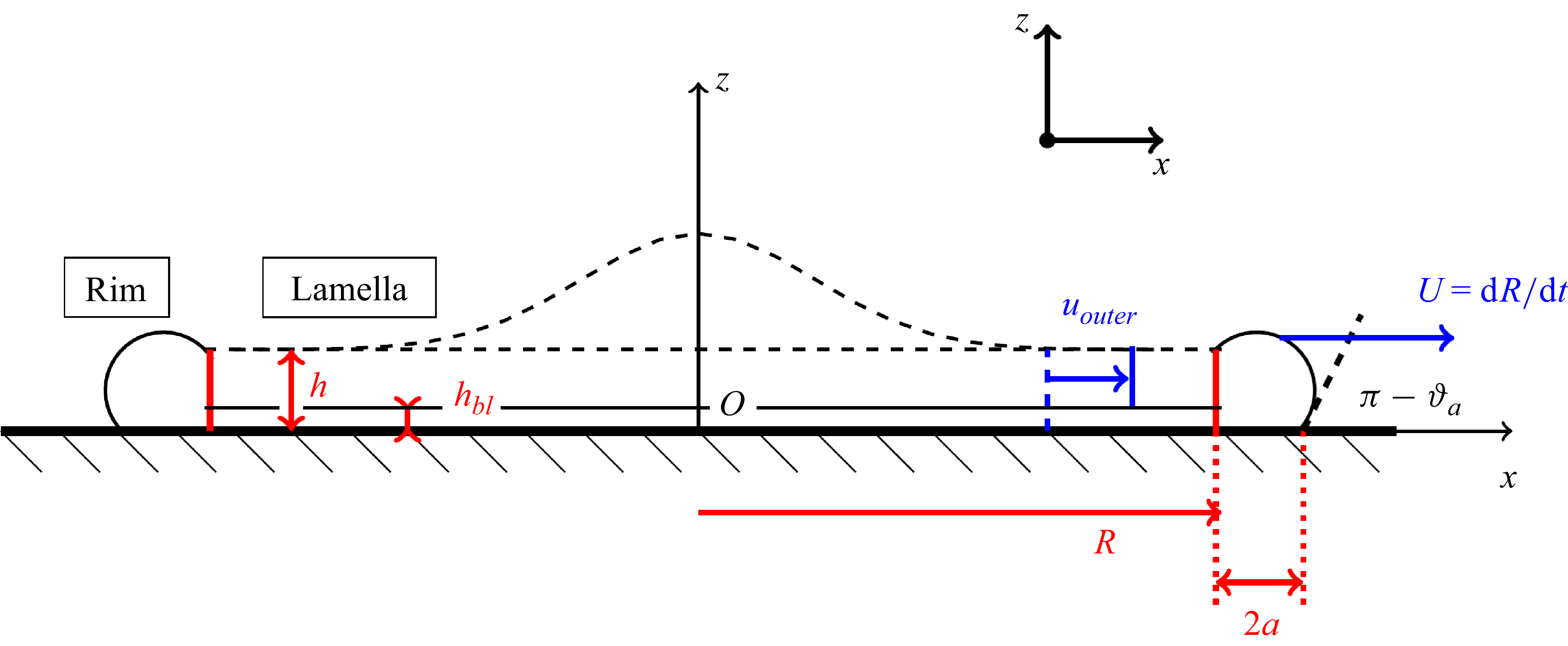

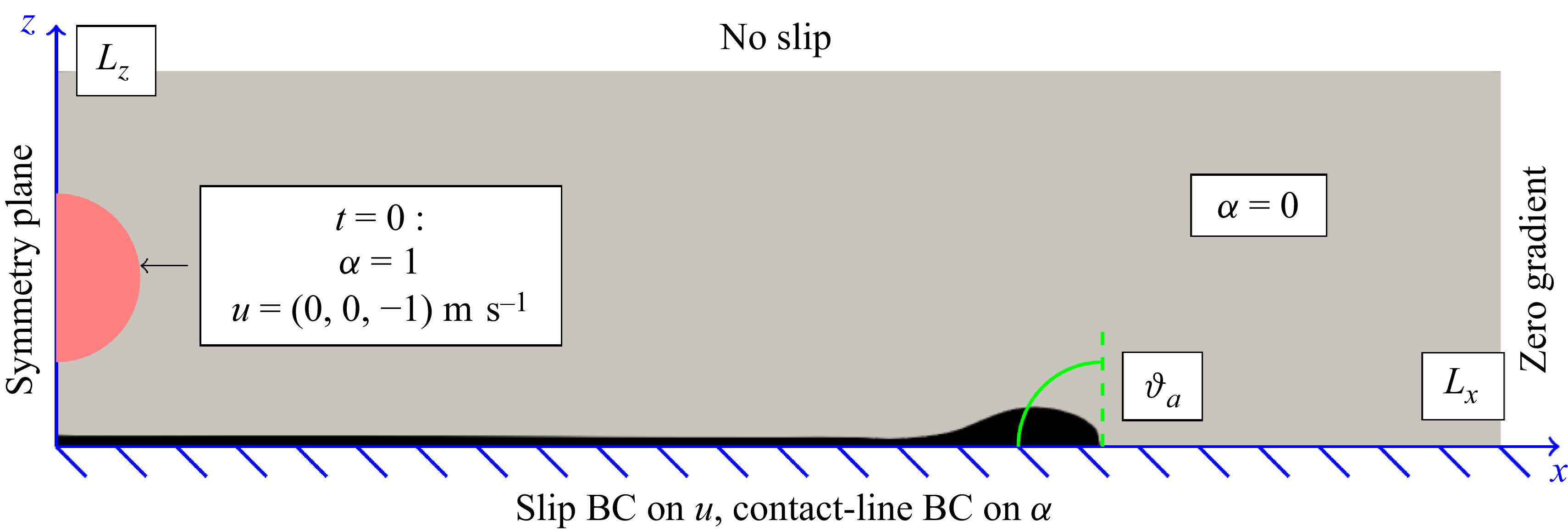

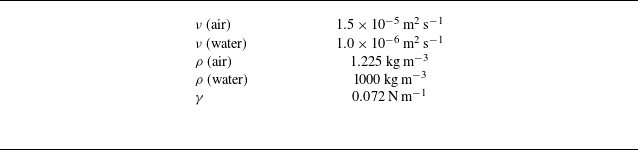

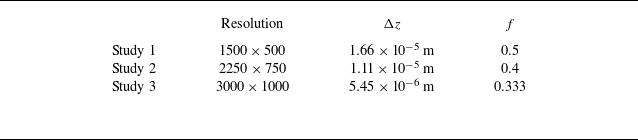

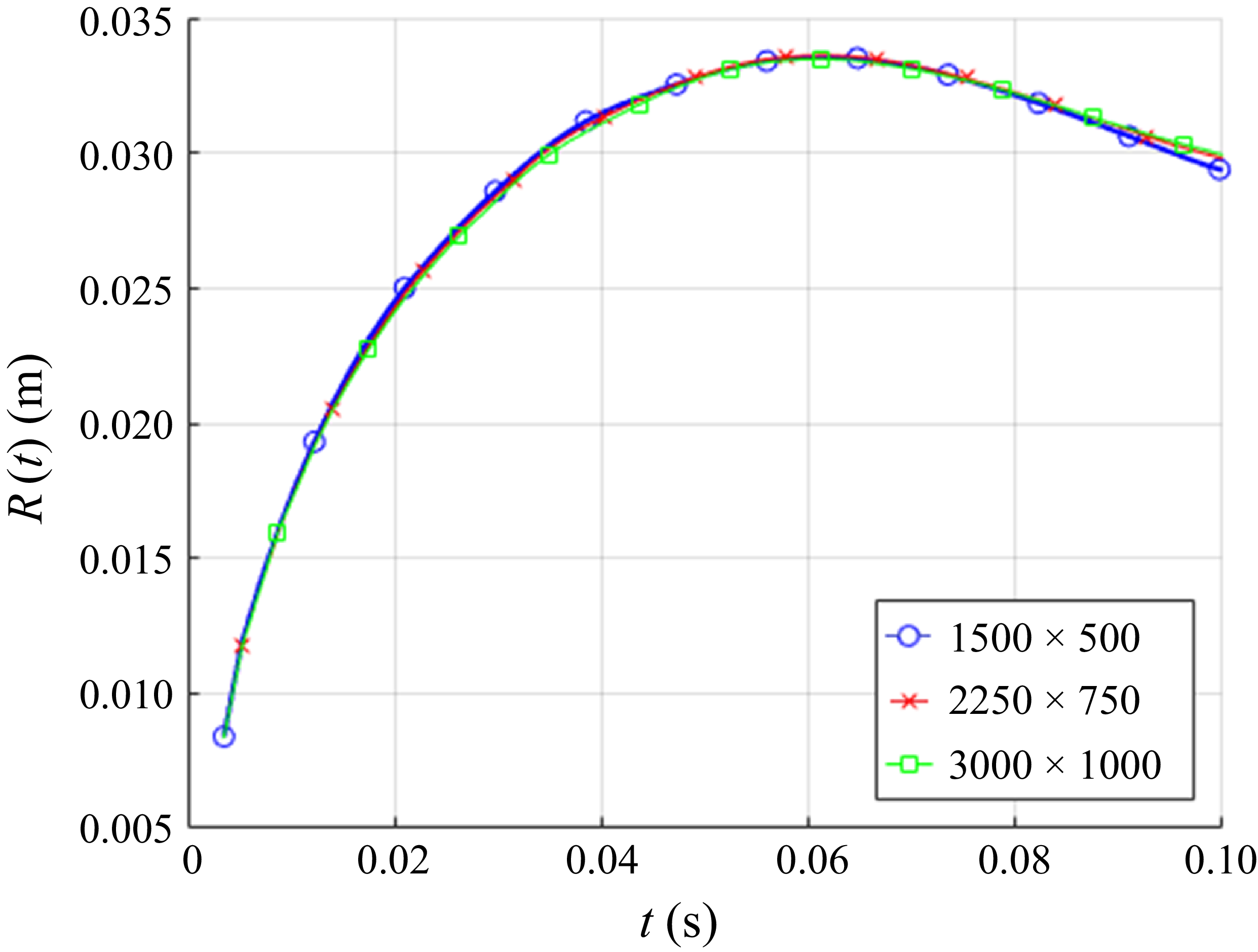

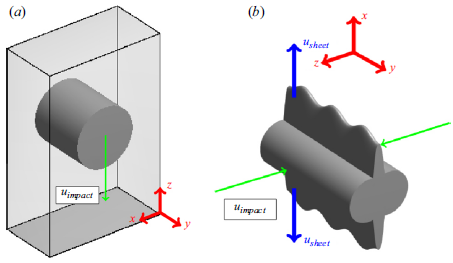

We introduce a RL model for 2-D droplets, based on the analogous one for 3-D axisymmetric droplets given by Bustamante & Ó Náraigh (Reference Bustamante and Ó Náraigh2025) (but see also Eggers et al. (Reference Eggers, Fontelos, Josserand and Zaleski2010) and Gordillo et al. (Reference Gordillo, Riboux and Quintero2019)). The schematic diagram is presented in figure 1. The diagram shows the development of the RL structure at a time

![]() $\tau$

after the initial droplet impact. A hyperbolic flow arises from the droplet impact after a characteristic time

$\tau$

after the initial droplet impact. A hyperbolic flow arises from the droplet impact after a characteristic time

![]() $t_0$

, the horizontal component of which drives the flow in the lamella. Air resistance and compressibility are neglected in the derivations, which is appropriate for the range of Reynolds and Weber numbers considered in the work, together with the implied droplet length scale

$t_0$

, the horizontal component of which drives the flow in the lamella. Air resistance and compressibility are neglected in the derivations, which is appropriate for the range of Reynolds and Weber numbers considered in the work, together with the implied droplet length scale

![]() $R_0=O\,(\mathrm{mm})$

. We work through the different elements of the model, starting with the flow in the lamella.

$R_0=O\,(\mathrm{mm})$

. We work through the different elements of the model, starting with the flow in the lamella.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram showing the cross-section of a 2-D RL structure. Dashed curved line: true lamella height

![]() $h(x,t)=(t+t_0)^{-1}f[(x/(t+t_0)]+h_{\textit{PI}}(t)$

, as given by (2.6). Dashed straight line: the remote asymptotic approximation

$h(x,t)=(t+t_0)^{-1}f[(x/(t+t_0)]+h_{\textit{PI}}(t)$

, as given by (2.6). Dashed straight line: the remote asymptotic approximation

![]() $h(x,t)=h_{\textit{init}}(\tau +t_0)/(t+t_0)+h_{\textit{PI}}(t)$

.

$h(x,t)=h_{\textit{init}}(\tau +t_0)/(t+t_0)+h_{\textit{PI}}(t)$

.

We emphasise that in this work, we use a RL model to place bounds on the maximum value of

![]() $R$

. However, from figure 1, it can be seen that

$R$

. However, from figure 1, it can be seen that

![]() $\mathcal{R}_{\textit{max}}=R+2a$

, where

$\mathcal{R}_{\textit{max}}=R+2a$

, where

![]() $\mathcal{R}_{\textit{max}}$

is the quantity of interest. However, in § 4 we will demonstrate that

$\mathcal{R}_{\textit{max}}$

is the quantity of interest. However, in § 4 we will demonstrate that

![]() $2a$

is negligibly small compared with

$2a$

is negligibly small compared with

![]() $R$

, and hence can be ignored.

$R$

, and hence can be ignored.

2.1. Flow in the lamella

The horizontal flow far from the substrate is denoted by

![]() $u_{\textit{outer}}$

(the outer flow). Similar to the 3-D axisymmetric case, this is assumed to be a hyperbolic flow and is given (in 2-D Cartesian coordinates) by the expression

$u_{\textit{outer}}$

(the outer flow). Similar to the 3-D axisymmetric case, this is assumed to be a hyperbolic flow and is given (in 2-D Cartesian coordinates) by the expression

where

![]() $t_0$

is a model parameter which describes the onset time of the flow, prior to the formation of the RL structure. The assumption of this hyperbolic flow profile in the lamella is justified by earlier simulations of 2-D droplet impact (Ó Náraigh & Mairal Reference Ó Náraigh and Mairal2023).

$t_0$

is a model parameter which describes the onset time of the flow, prior to the formation of the RL structure. The assumption of this hyperbolic flow profile in the lamella is justified by earlier simulations of 2-D droplet impact (Ó Náraigh & Mairal Reference Ó Náraigh and Mairal2023).

A boundary layer forms close to the substrate, in which the fluid velocity transitions from

![]() $u_{\textit{outer}}$

to zero, across a distance

$u_{\textit{outer}}$

to zero, across a distance

![]() $h_{bl}$

, the boundary-layer thickness. From boundary-layer theory (White et al. Reference Frank2011), the boundary-layer thickness scales as

$h_{bl}$

, the boundary-layer thickness. From boundary-layer theory (White et al. Reference Frank2011), the boundary-layer thickness scales as

![]() $h_{bl}\propto \sqrt {\nu x/u_{\textit{outer}}}$

, where

$h_{bl}\propto \sqrt {\nu x/u_{\textit{outer}}}$

, where

![]() $\nu =\mu /\rho$

is the kinematic viscosity of the liquid. Given the functional form of

$\nu =\mu /\rho$

is the kinematic viscosity of the liquid. Given the functional form of

![]() $u_{\textit{outer}}$

, the

$u_{\textit{outer}}$

, the

![]() $x$

-dependence cancels out, to give

$x$

-dependence cancels out, to give

![]() $h_{bl}\propto \sqrt {\nu (t+t_0)}$

. We allow for an additional degree of freedom in the problem by taking

$h_{bl}\propto \sqrt {\nu (t+t_0)}$

. We allow for an additional degree of freedom in the problem by taking

![]() $h_{bl}\propto \sqrt {\nu (t+t_1)}$

, where

$h_{bl}\propto \sqrt {\nu (t+t_1)}$

, where

![]() $t_1$

describes the time of formation of the boundary layer (Eggers et al. Reference Eggers, Fontelos, Josserand and Zaleski2010). Following boundary-layer theory (White et al. Reference Frank2011), we describe the vertical variation of the flow using a transition function, such that

$t_1$

describes the time of formation of the boundary layer (Eggers et al. Reference Eggers, Fontelos, Josserand and Zaleski2010). Following boundary-layer theory (White et al. Reference Frank2011), we describe the vertical variation of the flow using a transition function, such that

where

![]() $F(z=0)=0$

and

$F(z=0)=0$

and

![]() $F(z)=1$

for

$F(z)=1$

for

![]() $z\geq h_{bl}$

. For simplicity, and following Bustamante & Ó Náraigh (Reference Bustamante and Ó Náraigh2025) and Eggers et al. (Reference Eggers, Fontelos, Josserand and Zaleski2010) for the 3-D axisymmetric case, we use a step function for the transition function, such that

$z\geq h_{bl}$

. For simplicity, and following Bustamante & Ó Náraigh (Reference Bustamante and Ó Náraigh2025) and Eggers et al. (Reference Eggers, Fontelos, Josserand and Zaleski2010) for the 3-D axisymmetric case, we use a step function for the transition function, such that

\begin{align} F(z)=\begin{cases} 0,& z\lt h_{bl},\\ 1,& z\gt h_{bl}.\end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} F(z)=\begin{cases} 0,& z\lt h_{bl},\\ 1,& z\gt h_{bl}.\end{cases} \end{align}

We have used the notation

![]() $u(x,z,t)$

for the flow in the horizontal direction; the corresponding flow in the vertical direction is denoted by

$u(x,z,t)$

for the flow in the horizontal direction; the corresponding flow in the vertical direction is denoted by

![]() $w(x,z,t)$

. We use the incompressibility condition

$w(x,z,t)$

. We use the incompressibility condition

![]() $\partial _x u+\partial _z w=0$

to obtain an expression for

$\partial _x u+\partial _z w=0$

to obtain an expression for

![]() $w(x,z,t)$

$w(x,z,t)$

\begin{align} w(x,z,t)=\begin{cases} 0,& z\lt h_{bl},\\ -\dfrac {z-h_{bl}}{t+t_0},&z\gt h_{bl}.\end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} w(x,z,t)=\begin{cases} 0,& z\lt h_{bl},\\ -\dfrac {z-h_{bl}}{t+t_0},&z\gt h_{bl}.\end{cases} \end{align}

2.2. Lamella height

To model the lamella height

![]() $h(x,t)$

, we assume the kinematic condition, such that the interface

$h(x,t)$

, we assume the kinematic condition, such that the interface

![]() $h(x,t)$

moves with the flow. Hence, the height of the lamella

$h(x,t)$

moves with the flow. Hence, the height of the lamella

![]() $h(x,t)$

satisfies

$h(x,t)$

satisfies

In the remainder of this section, we assume we are in phase 1 of the motion, such that

![]() $h(R,t)\gt h_{bl}$

, and such that

$h(R,t)\gt h_{bl}$

, and such that

![]() $(u,w)_{z=h}\neq 0$

. We discuss phase 2 of the motion, wherein

$(u,w)_{z=h}\neq 0$

. We discuss phase 2 of the motion, wherein

![]() $h(R,t)$

reaches a limiting value set by the boundary layer, and

$h(R,t)$

reaches a limiting value set by the boundary layer, and

![]() $(u,w)_{z=h}=0$

in § 4. Thus, (2.5) becomes

$(u,w)_{z=h}=0$

in § 4. Thus, (2.5) becomes

Equation (2.6) has an exact solution (valid in phase 1) by the method of characteristics

\begin{align} h(x,t)=\frac {\tau +t_0}{t+t_0}f \!\left (x\frac {\tau +t_0}{t+t_0}\right )+ \underbrace {\frac {2}{3}\left [h_{bl}(t)\frac {t+t_1}{t+t_0}-h_{bl}(\tau )\frac {\tau +t_1}{t+t_0}\right ]}_{=h_{\textit{PI}}(t)}\qquad t\geq \tau , \end{align}

\begin{align} h(x,t)=\frac {\tau +t_0}{t+t_0}f \!\left (x\frac {\tau +t_0}{t+t_0}\right )+ \underbrace {\frac {2}{3}\left [h_{bl}(t)\frac {t+t_1}{t+t_0}-h_{bl}(\tau )\frac {\tau +t_1}{t+t_0}\right ]}_{=h_{\textit{PI}}(t)}\qquad t\geq \tau , \end{align}

where

![]() $f$

is set by the initial conditions. At late times,

$f$

is set by the initial conditions. At late times,

![]() $f$

is taken to be a constant function, which is the so-called remote asymptotic solution (Roisman Reference Roisman2009). Here, we use the parameter

$f$

is taken to be a constant function, which is the so-called remote asymptotic solution (Roisman Reference Roisman2009). Here, we use the parameter

![]() $\tau$

to denote the initial time

$\tau$

to denote the initial time

![]() $t=\tau$

at which point the RL structure seen in figure 1 forms. As in the 3-D axisymmetric case (Marengo et al. Reference Marengo, Antonini, Roisman and Tropea2011), the contribution

$t=\tau$

at which point the RL structure seen in figure 1 forms. As in the 3-D axisymmetric case (Marengo et al. Reference Marengo, Antonini, Roisman and Tropea2011), the contribution

![]() $h_{\textit{PI}}(t)$

is the viscous correction, it is positive definite and, as such, represents a thickening of the lamella compared with the inviscid scenario.

$h_{\textit{PI}}(t)$

is the viscous correction, it is positive definite and, as such, represents a thickening of the lamella compared with the inviscid scenario.

2.3. Mass conservation

We derive an Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) for the volume of the rim in what follows. We omit the redundant dimension out of the plane of the page, which carries with it a factor of

![]() $\lambda$

, this being the length of the idealised cylindrical droplet. Hence, we work with the rim area

$\lambda$

, this being the length of the idealised cylindrical droplet. Hence, we work with the rim area

![]() $V$

, the lamella area

$V$

, the lamella area

![]() $2\int _0^R \mathrm{d} x\int _0^{h(x,t)}\mathrm{d} z$

and the total area

$2\int _0^R \mathrm{d} x\int _0^{h(x,t)}\mathrm{d} z$

and the total area

![]() $V_{\textit{tot}}$

, such that

$V_{\textit{tot}}$

, such that

We use

![]() $\mathrm{d} V_{\textit{tot}}/\mathrm{d} t=0$

and (2.6) to get

$\mathrm{d} V_{\textit{tot}}/\mathrm{d} t=0$

and (2.6) to get

where

![]() $R$

denotes the greatest extent of the lamella at time

$R$

denotes the greatest extent of the lamella at time

![]() $t$

, and where we henceforth use the simplified notation

$t$

, and where we henceforth use the simplified notation

By mass conservation, (2.9) has exact solution

where

![]() $g(s)=\int _0^s f\!(s)\,\mathrm{d} s$

.

$g(s)=\int _0^s f\!(s)\,\mathrm{d} s$

.

2.4. Momentum

In a similar way, we derive an ODE for the momentum of the rim. We work with one half of the rim momentum

![]() $P$

, and one half of the lamella momentum

$P$

, and one half of the lamella momentum

![]() $\rho \int _0^R \mathrm{d} x\int _0^{h(x,t)}\mathrm{d} z$

, such that the total momentum in (say) the right-hand half of the RL structure in figure 1 is

$\rho \int _0^R \mathrm{d} x\int _0^{h(x,t)}\mathrm{d} z$

, such that the total momentum in (say) the right-hand half of the RL structure in figure 1 is

where again,

![]() $\lambda$

is the length of the idealised cylindrical droplet in the plane of the page. When

$\lambda$

is the length of the idealised cylindrical droplet in the plane of the page. When

![]() $h\gt h_{bl}$

(phase 1) this becomes

$h\gt h_{bl}$

(phase 1) this becomes

\begin{align} P_{\textit{tot}}=P+\underbrace {\rho \lambda \int _0^R \frac {x}{t+t_0}\left [h(x,t)-h_{bl}(t)\right ]\mathrm{d} x}_{=P_{\textit{lam}}}. \end{align}

\begin{align} P_{\textit{tot}}=P+\underbrace {\rho \lambda \int _0^R \frac {x}{t+t_0}\left [h(x,t)-h_{bl}(t)\right ]\mathrm{d} x}_{=P_{\textit{lam}}}. \end{align}

By direct differentiation, we have

By Newton’s second law, we have

Here,

![]() $\vartheta _a$

is the advancing contact angle, assumed for the present purposes to be constant. Hence, combining (2.14) and (2.15) and using

$\vartheta _a$

is the advancing contact angle, assumed for the present purposes to be constant. Hence, combining (2.14) and (2.15) and using

![]() $h\equiv h(R,t)$

we have

$h\equiv h(R,t)$

we have

We use

![]() $\mathrm{d} P/\mathrm{d} t=\rho \lambda U (\mathrm{d} V_{1/2}/\mathrm{d} t)+\rho \lambda V_{1/2}(\mathrm{d} U/\mathrm{d} t)$

(

$\mathrm{d} P/\mathrm{d} t=\rho \lambda U (\mathrm{d} V_{1/2}/\mathrm{d} t)+\rho \lambda V_{1/2}(\mathrm{d} U/\mathrm{d} t)$

(

![]() $V_{1/2}$

is half the rim area) and

$V_{1/2}$

is half the rim area) and

![]() $U\equiv \dot R$

to re-write the momentum equation in a final form

$U\equiv \dot R$

to re-write the momentum equation in a final form

Here, we have divided out by the redundant length scale

![]() $\lambda$

, and we have introduced the notation

$\lambda$

, and we have introduced the notation

![]() $u_0\equiv R/(t+t_0)$

.

$u_0\equiv R/(t+t_0)$

.

2.5. Summary of the model equations

We gather up the model equations here in one place. We emphasise that the equations are for phase 1 of the motion, wherein

![]() $h(t)\gt h_{bl}(t)$

$h(t)\gt h_{bl}(t)$

\begin{align} V\frac {\mathrm{d} U}{\mathrm{d} t}&=2\big [(u_0-U)^2\left (h-h_{bl}\right )+U^2h_{bl}\big ]\nonumber \\&\quad +\frac {1}{2}\frac {h_{bl} R^2}{(t+t_0)(t+t_1)}-2\frac {\gamma }{\rho }(1-\cos \vartheta _a), \\[9pt] \nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} V\frac {\mathrm{d} U}{\mathrm{d} t}&=2\big [(u_0-U)^2\left (h-h_{bl}\right )+U^2h_{bl}\big ]\nonumber \\&\quad +\frac {1}{2}\frac {h_{bl} R^2}{(t+t_0)(t+t_1)}-2\frac {\gamma }{\rho }(1-\cos \vartheta _a), \\[9pt] \nonumber \end{align}

where

![]() $h$

is given by (2.10), and

$h$

is given by (2.10), and

![]() $u_0=R/(t+t_0)$

. We analyse (2.18) in the following sections.

$u_0=R/(t+t_0)$

. We analyse (2.18) in the following sections.

3. Inviscid case

In this section we look at the RL model (2.18) in the inviscid case, which can be obtained by shrinking the boundary layer

![]() $h_{bl}$

to zero. Hence, the model simplifies

$h_{bl}$

to zero. Hence, the model simplifies

The corresponding RL model in the 3-D axisymmetric case has a geometric factor of

![]() $2\pi R$

on the right-hand side of both the mass-conservation equation and the momentum equation (Amirfazli et al. Reference Amirfazli, Bustamante, Hu and Ó Náraigh2024). The fact that this factor does not occur in 2-D RL model (3.1) means that it has an exact solution, which we present here.

$2\pi R$

on the right-hand side of both the mass-conservation equation and the momentum equation (Amirfazli et al. Reference Amirfazli, Bustamante, Hu and Ó Náraigh2024). The fact that this factor does not occur in 2-D RL model (3.1) means that it has an exact solution, which we present here.

3.1. Exact solution

As in the 3-D axisymmetric model, we introduce the velocity defect

![]() $\varDelta =u_0-U$

. (3.1) can then be recast in terms of an ODE for

$\varDelta =u_0-U$

. (3.1) can then be recast in terms of an ODE for

![]() $\varDelta$

$\varDelta$

where

is the Taylor–Culick speed (

![]() $c$

is time-dependent, through

$c$

is time-dependent, through

![]() $h$

). We further recast (3.2) as an ODE for

$h$

). We further recast (3.2) as an ODE for

![]() $V \kern-1pt \Delta$

$V \kern-1pt \Delta$

Thus, there is an exact solution for

![]() $V \kern-1pt \Delta$

$V \kern-1pt \Delta$

where

![]() $V_{\textit{init}}$

denotes the initial condition, i.e.

$V_{\textit{init}}$

denotes the initial condition, i.e.

![]() $V$

evaluated at

$V$

evaluated at

![]() $t=\tau$

, and similarly for

$t=\tau$

, and similarly for

![]() $\varDelta _{\textit{init}}$

. We recall the definition of

$\varDelta _{\textit{init}}$

. We recall the definition of

![]() $\varDelta$

, to obtain

$\varDelta$

, to obtain

This can be further re-written as

\begin{align} \frac {\mathrm{d} }{\mathrm{d} t}\left (\frac {R}{t+t_0}\right )=-\frac {V_{\textit{init}}}{V}\frac {\varDelta _{\textit{init}}}{t+t_0}\left (\frac {\tau +t_0}{t+t_0}\right )-\frac {\gamma }{\rho }\frac {\left (1-\cos \vartheta _a\right )}{V}\left [1-\left (\frac {\tau +t_0}{t+t_0}\right )^2\right ]\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\mathrm{d} }{\mathrm{d} t}\left (\frac {R}{t+t_0}\right )=-\frac {V_{\textit{init}}}{V}\frac {\varDelta _{\textit{init}}}{t+t_0}\left (\frac {\tau +t_0}{t+t_0}\right )-\frac {\gamma }{\rho }\frac {\left (1-\cos \vartheta _a\right )}{V}\left [1-\left (\frac {\tau +t_0}{t+t_0}\right )^2\right ]\!. \end{align}

To make further progress, we take

![]() $f$

to be a constant in (2.7) for

$f$

to be a constant in (2.7) for

![]() $h(R,t)\equiv h$

. This approximation is valid at late times and is pursued here for mathematical convenience. The foregoing analysis is still valid without this approximation, but would become intractable. Hence, we obtain

$h(R,t)\equiv h$

. This approximation is valid at late times and is pursued here for mathematical convenience. The foregoing analysis is still valid without this approximation, but would become intractable. Hence, we obtain

We further assume that the lamella has flattened into a rectangular shape, hence

![]() $V=V_{\textit{tot}}-2R[(\tau +t_0)/(t+t_0)]h_{\textit{init}}$

, an assumption discussed in more detail below (§ 3.3). We also group together the terms

$V=V_{\textit{tot}}-2R[(\tau +t_0)/(t+t_0)]h_{\textit{init}}$

, an assumption discussed in more detail below (§ 3.3). We also group together the terms

![]() $R[(\tau +t_0)/(t+t_0)]$

as

$R[(\tau +t_0)/(t+t_0)]$

as

![]() $\eta$

. Thus, we have

$\eta$

. Thus, we have

\begin{align} \frac {\mathrm{d}\eta }{\mathrm{d} t}=-\varDelta _{\textit{init}}\frac {V_{\textit{init}}}{V_{\textit{tot}}-2\eta h_{\textit{init}}}\left (\frac {\tau +t_0}{t+t_0}\right )^2-\frac {\gamma (\tau +t_0)}{\rho }\frac {\left (1-\cos \vartheta _a\right )}{V_{\textit{tot}}-2\eta h_{\textit{init}}}\left [1-\left (\frac {\tau +t_0}{t+t_0}\right )^2\right ]\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\mathrm{d}\eta }{\mathrm{d} t}=-\varDelta _{\textit{init}}\frac {V_{\textit{init}}}{V_{\textit{tot}}-2\eta h_{\textit{init}}}\left (\frac {\tau +t_0}{t+t_0}\right )^2-\frac {\gamma (\tau +t_0)}{\rho }\frac {\left (1-\cos \vartheta _a\right )}{V_{\textit{tot}}-2\eta h_{\textit{init}}}\left [1-\left (\frac {\tau +t_0}{t+t_0}\right )^2\right ]\!. \end{align}

This is a separable ODE. Following the steps outlined in Appendix B, (3.9) can be solved to yield

where

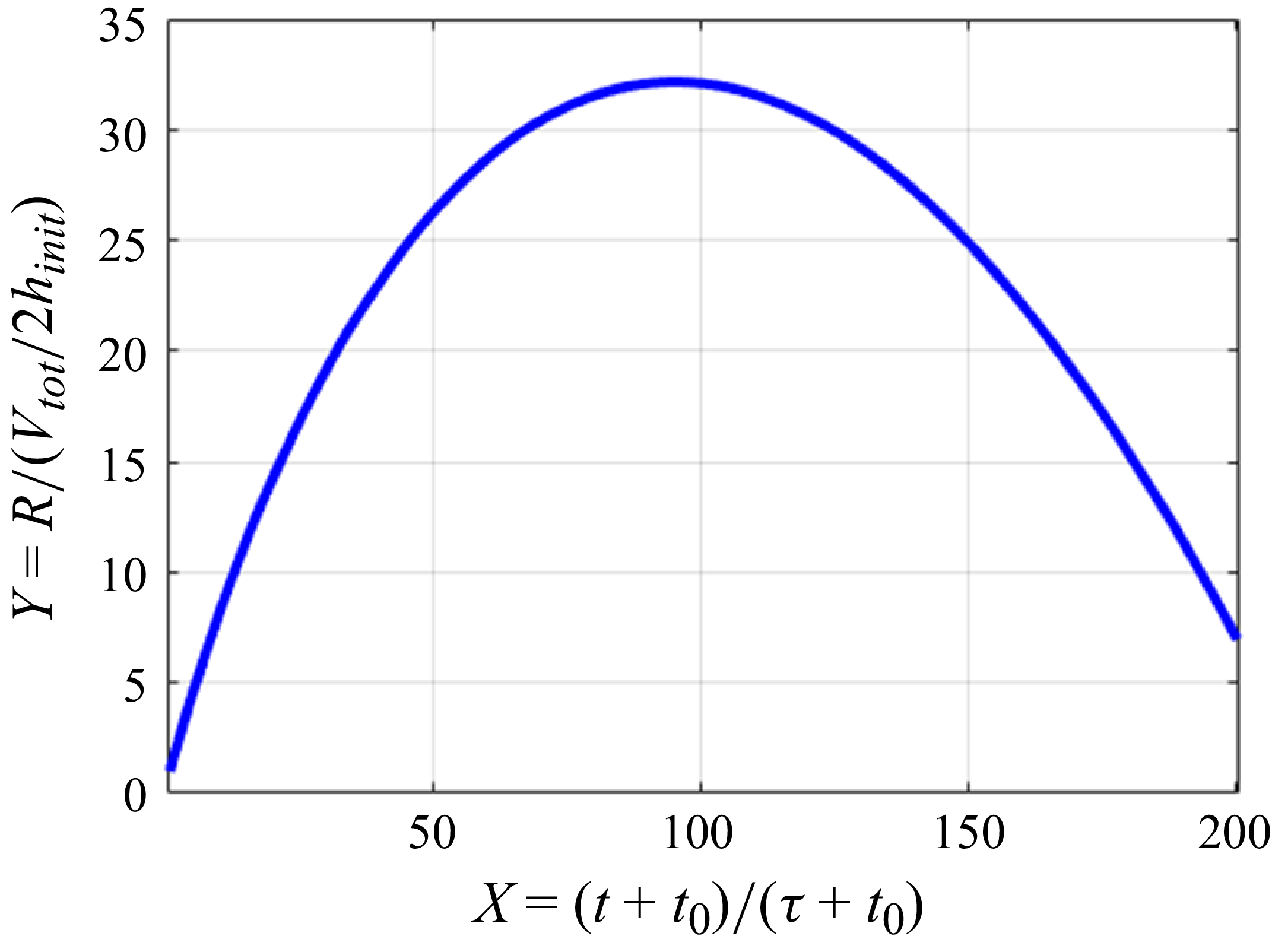

Equation (3.10) is the required exact solution of the RL model. A sample solution at

![]() ${\textit{We}}=100$

is shown in figure 2.

${\textit{We}}=100$

is shown in figure 2.

3.2. Maximum spreading radius

The maximum spreading occurs at

![]() $\mathrm{d} R/\mathrm{d} t=0$

, hence

$\mathrm{d} R/\mathrm{d} t=0$

, hence

![]() $\mathrm{d} Y/\mathrm{d} X=0$

. Based on (3.10), this occurs when

$\mathrm{d} Y/\mathrm{d} X=0$

. Based on (3.10), this occurs when

Assuming the maximum spreading occurs at large value of

![]() $t$

(hence,

$t$

(hence,

![]() $X$

), this gives

$X$

), this gives

![]() $X\approx 4/(9A)$

, a result which will be verified a posteriori. Correspondingly,

$X\approx 4/(9A)$

, a result which will be verified a posteriori. Correspondingly,

By using the explicit definition of

![]() $A$

from (3.11) we have (details in Appendix B)

$A$

from (3.11) we have (details in Appendix B)

In order for the large-

![]() $X$

approximation to be valid, we require

$X$

approximation to be valid, we require

![]() $A$

to be small, and hence

$A$

to be small, and hence

![]() ${\textit{We}}$

to be large. Thus, (3.14) is valid in the large Weber number limit. This scaling behaviour (

${\textit{We}}$

to be large. Thus, (3.14) is valid in the large Weber number limit. This scaling behaviour (

![]() $\mathcal{R}_{\textit{max}}/R_0\sim {\textit{We}}$

, for

$\mathcal{R}_{\textit{max}}/R_0\sim {\textit{We}}$

, for

![]() ${\textit{We}}\gg 1$

) is exactly what is seen in previous published work on 2-D droplet impact (Ó Náraigh & Mairal Reference Ó Náraigh and Mairal2023), and is consistent with the energy-budget analysis (1.5).

${\textit{We}}\gg 1$

) is exactly what is seen in previous published work on 2-D droplet impact (Ó Náraigh & Mairal Reference Ó Náraigh and Mairal2023), and is consistent with the energy-budget analysis (1.5).

3.3. Parameter estimation

In order to make a systematic comparison between (3.14) and both the correlation (1.5) and numerical simulations, it is necessary to estimate the pre-factors in (3.14).

Following Amirfazli et al. (Reference Amirfazli, Bustamante, Hu and Ó Náraigh2024) for the RL model in 3-D axisymmetry (inviscid case), we estimate

![]() $h_{\textit{init}}/(\tau +t_0)$

as

$h_{\textit{init}}/(\tau +t_0)$

as

![]() $U_0$

, hence

$U_0$

, hence

We estimate

![]() $h_{\textit{init}}$

using dimensional analysis. Hence, we assume that at the onset of the RL phase, the rim is small compared with the lamella, hence

$h_{\textit{init}}$

using dimensional analysis. Hence, we assume that at the onset of the RL phase, the rim is small compared with the lamella, hence

![]() $V_{\textit{init}}=0$

. We crudely approximate the lamella as a rectangle of sides of length

$V_{\textit{init}}=0$

. We crudely approximate the lamella as a rectangle of sides of length

![]() $2R_{\textit{init}}$

and

$2R_{\textit{init}}$

and

![]() $h_{\textit{init}}$

. On grounds of dimensional analysis, we can say that an estimation based on a more complex lamella shape will yield similar results, although the prefactors in the foregoing analysis will change.

$h_{\textit{init}}$

. On grounds of dimensional analysis, we can say that an estimation based on a more complex lamella shape will yield similar results, although the prefactors in the foregoing analysis will change.

An energy balance at this instant gives

In more detail, this expression is:

\begin{align}& \rho \int _0^{R_{\textit{init}}}\int _0^{h_{\textit{init}}}\left [\left (\frac {x}{\tau +t_0}\right )^2+\left (\frac {z}{\tau +t_0}\right )^2 \right ]\mathrm{d} x\,\mathrm{d} z+[2R_{\textit{init}}(1-\cos \vartheta _a)+2h_{\textit{init}}]\gamma \nonumber \\&\quad = \gamma (2\pi R_0)+\frac {1}{2}\rho V_{\textit{tot}}U_0^2. \end{align}

\begin{align}& \rho \int _0^{R_{\textit{init}}}\int _0^{h_{\textit{init}}}\left [\left (\frac {x}{\tau +t_0}\right )^2+\left (\frac {z}{\tau +t_0}\right )^2 \right ]\mathrm{d} x\,\mathrm{d} z+[2R_{\textit{init}}(1-\cos \vartheta _a)+2h_{\textit{init}}]\gamma \nonumber \\&\quad = \gamma (2\pi R_0)+\frac {1}{2}\rho V_{\textit{tot}}U_0^2. \end{align}

We evaluate the integral, and use the fact that

![]() $V_{\textit{tot}}=2R_{\textit{init}}h_{\textit{init}}=\pi R_0^2$

, hence

$V_{\textit{tot}}=2R_{\textit{init}}h_{\textit{init}}=\pi R_0^2$

, hence

![]() $R_{\textit{init}}=V_{\textit{tot}}/(2h_{\textit{init}})$

. We further divide both sides by

$R_{\textit{init}}=V_{\textit{tot}}/(2h_{\textit{init}})$

. We further divide both sides by

![]() $\rho U_0^2 R_0^2$

. This gives

$\rho U_0^2 R_0^2$

. This gives

\begin{align}& \frac {1}{3} \frac {1}{R_0^2 U_0^2(\tau +t_0)^2}\left [ \left (\frac {V_{\textit{tot}}}{2h_{\textit{init}}}\right )^{\! 3} h_{\textit{init}} +\left (\frac {V_{\textit{tot}}}{2h_{\textit{init}}}\right )\! h_{\textit{init}}^3\right ] \nonumber\\&\quad +\frac {1}{R_0{\textit{We}}}\left [ 2\left (\frac {V_{\textit{tot}}}{2h_{\textit{init}}}\right )\left (1-\cos \vartheta _a\right )+2h_{\textit{init}}\right ]=\frac {2\pi }{\textit{We}}+\frac {1}{2}\pi .\end{align}

\begin{align}& \frac {1}{3} \frac {1}{R_0^2 U_0^2(\tau +t_0)^2}\left [ \left (\frac {V_{\textit{tot}}}{2h_{\textit{init}}}\right )^{\! 3} h_{\textit{init}} +\left (\frac {V_{\textit{tot}}}{2h_{\textit{init}}}\right )\! h_{\textit{init}}^3\right ] \nonumber\\&\quad +\frac {1}{R_0{\textit{We}}}\left [ 2\left (\frac {V_{\textit{tot}}}{2h_{\textit{init}}}\right )\left (1-\cos \vartheta _a\right )+2h_{\textit{init}}\right ]=\frac {2\pi }{\textit{We}}+\frac {1}{2}\pi .\end{align}

We multiply both sides by

![]() $h_{\textit{init}}^2$

and go over to the large-

$h_{\textit{init}}^2$

and go over to the large-

![]() ${\textit{We}}$

limit. This gives

${\textit{We}}$

limit. This gives

\begin{align} \frac {1}{3} \underbrace {\frac {h_{\textit{init}}^2}{U_0^2(\tau +t_0)^2}}_{=1}\frac {1}{R_0^2}\left [ \left (\frac {V_{\textit{tot}}}{2h_{\textit{init}}}\right )\!^3 h_{\textit{init}} +\left (\frac {V_{\textit{tot}}}{2h_{\textit{init}}}\right )\! h_{\textit{init}}^3\right ]\sim \frac {1}{2} \pi h_{\textit{init}}^2,\qquad {\textit{We}}\gg 1. \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {1}{3} \underbrace {\frac {h_{\textit{init}}^2}{U_0^2(\tau +t_0)^2}}_{=1}\frac {1}{R_0^2}\left [ \left (\frac {V_{\textit{tot}}}{2h_{\textit{init}}}\right )\!^3 h_{\textit{init}} +\left (\frac {V_{\textit{tot}}}{2h_{\textit{init}}}\right )\! h_{\textit{init}}^3\right ]\sim \frac {1}{2} \pi h_{\textit{init}}^2,\qquad {\textit{We}}\gg 1. \end{align}

After effecting cancellations, this simplifies to

We go back up to (3.15), with

![]() $h_{\textit{init}}^4\sim V_{\textit{tot}}^2/8$

for large

$h_{\textit{init}}^4\sim V_{\textit{tot}}^2/8$

for large

![]() ${\textit{We}}$

, hence

${\textit{We}}$

, hence

To two significant figures, this gives

![]() $R_{\textit{max}}/R_0\sim 0.47\,{\textit{We}}/(1-\cos \vartheta _a)$

, valid for

$R_{\textit{max}}/R_0\sim 0.47\,{\textit{We}}/(1-\cos \vartheta _a)$

, valid for

![]() ${\textit{We}} \gg 1$

.

${\textit{We}} \gg 1$

.

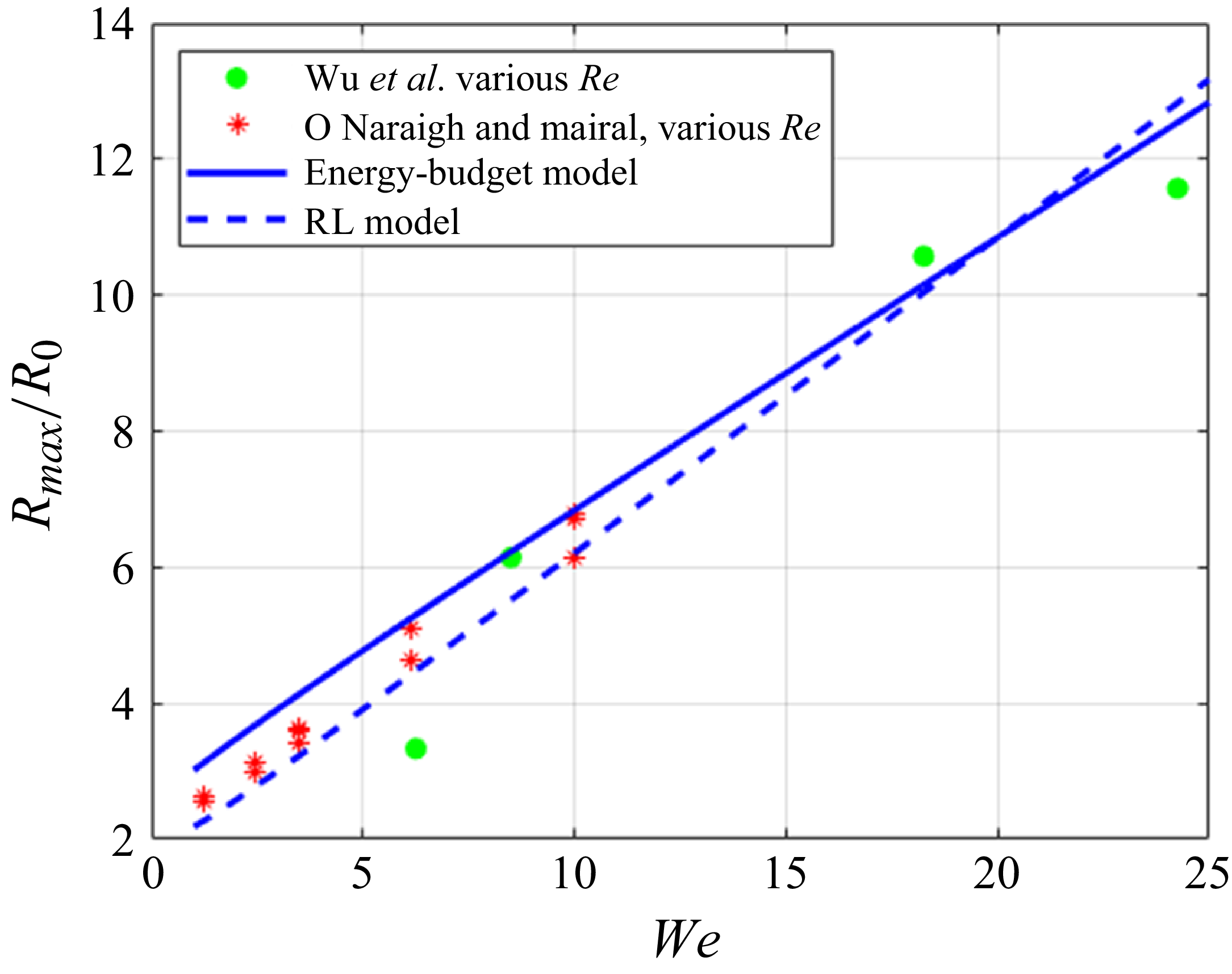

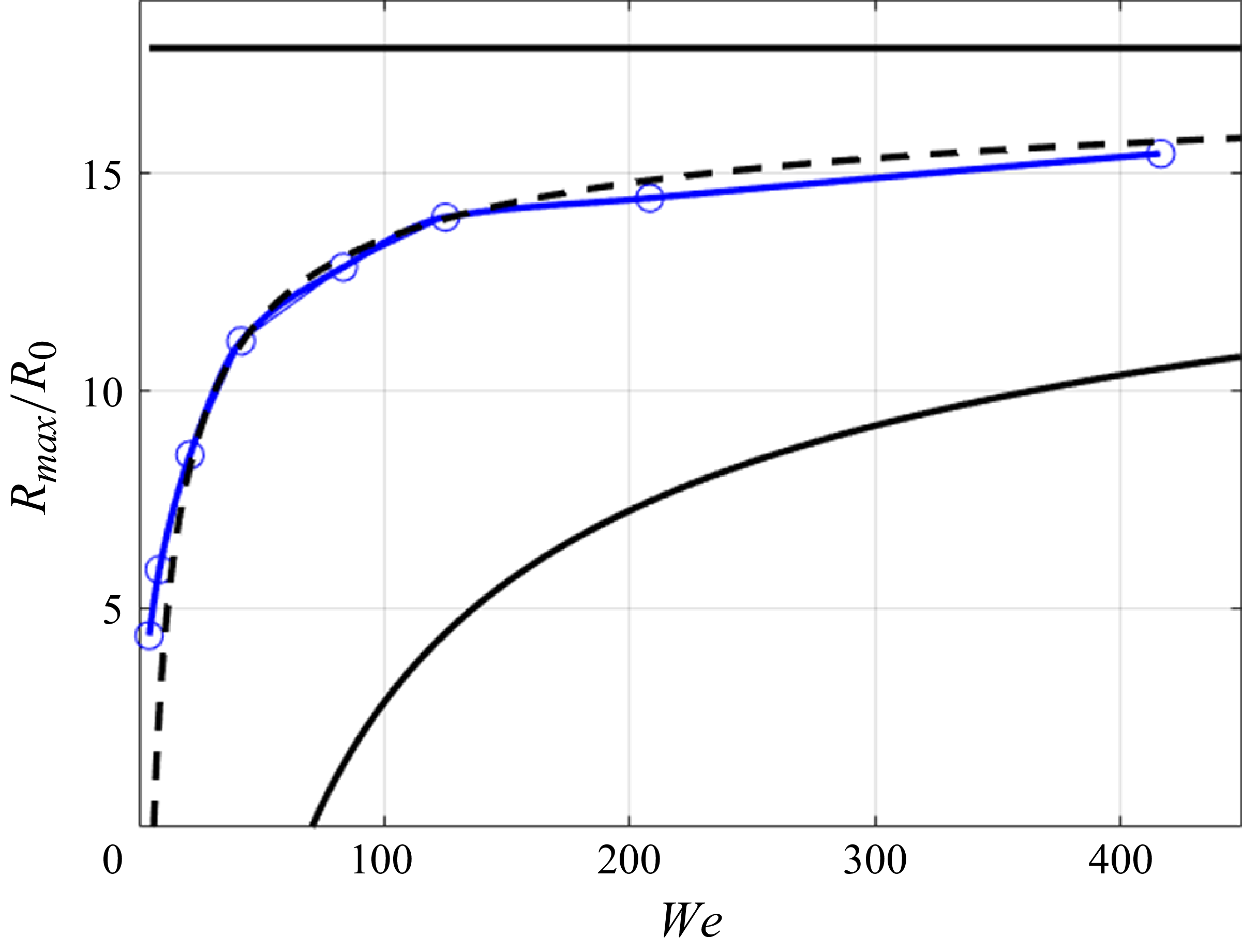

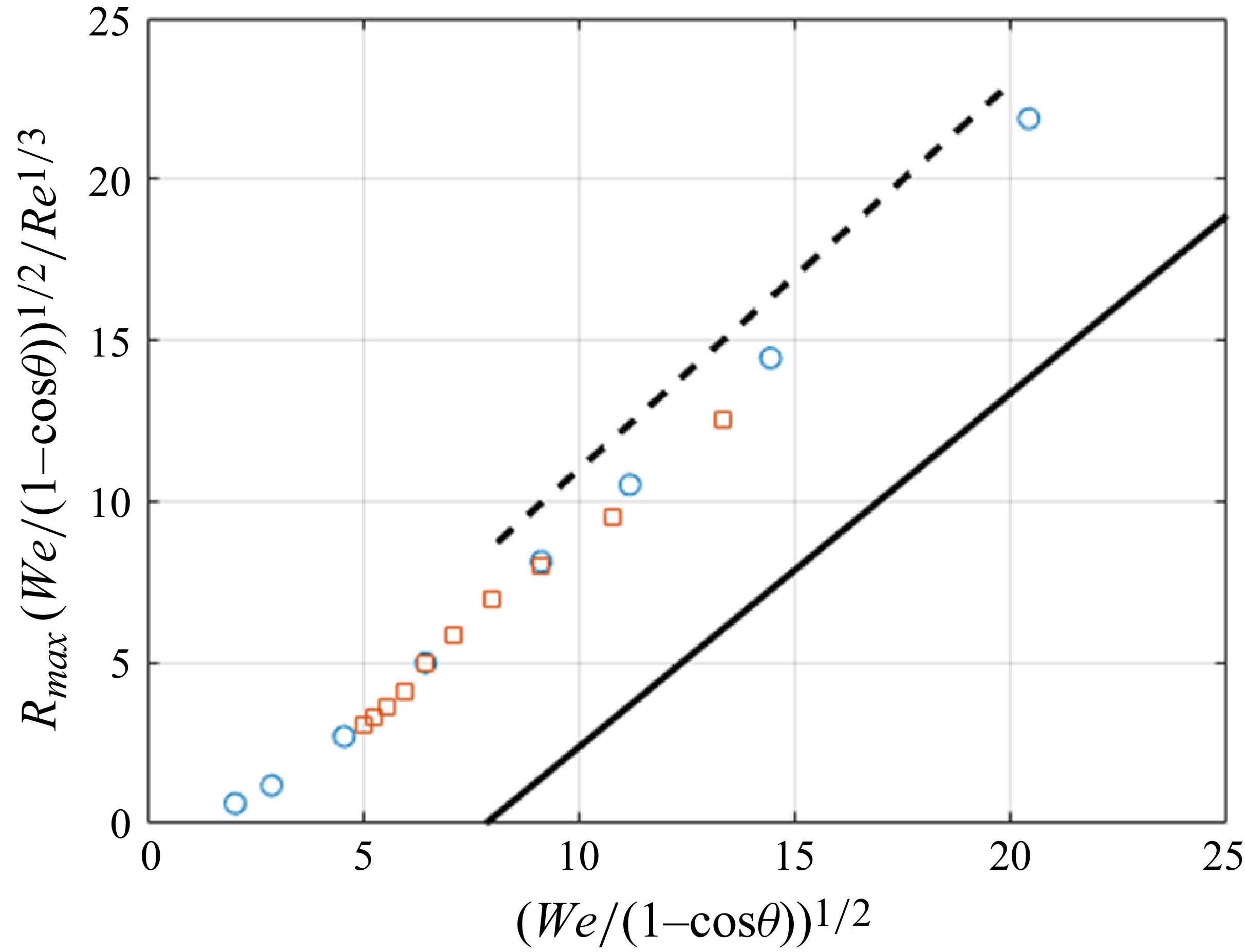

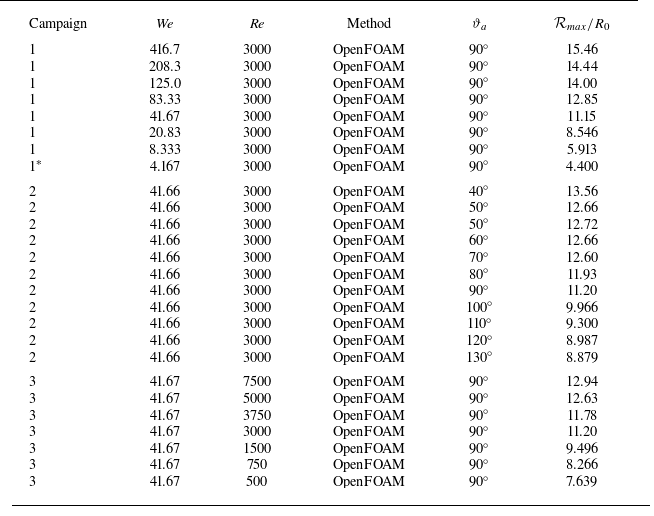

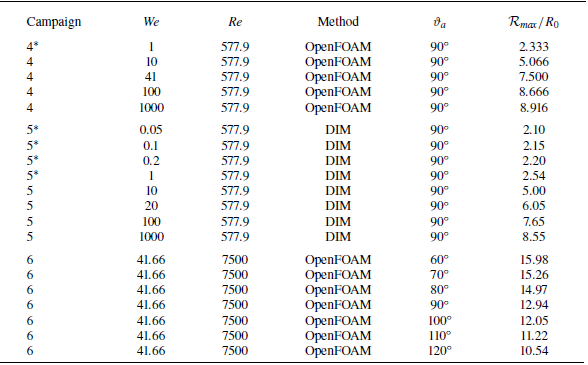

Figure 3. Comparison between the direct numerical simulation data of Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Gui, Yang, Tu and Jiang2021) and Ó Náraigh & Mairal (Reference Ó Náraigh and Mairal2023) and the theoretical models of droplet spreading. Solid line: energy-budget analysis ((1.2)), with

![]() $b=0.5$

. Dashed line: the RL model (3.10)–(3.11). The parameters in (3.11) have been selected using the methodology in § 3.3.

$b=0.5$

. Dashed line: the RL model (3.10)–(3.11). The parameters in (3.11) have been selected using the methodology in § 3.3.

3.4. Comparisons

We compare the result (3.21) with other results from the literature. First, we look at the energy budget (1.2) in the limit of large

![]() ${\textit{We}}$

and

${\textit{We}}$

and

![]() ${\textit{Re}}=\infty$

, which gives

${\textit{Re}}=\infty$

, which gives

Following the energy-budget results of Wildeman et al. (Reference Wildeman, Visser, Sun and Lohse2016) (albeit for 3-D axisymmetric droplets), we take

![]() $b=1/2$

as per the ‘head loss’ argument therein. To two significant figures, this gives

$b=1/2$

as per the ‘head loss’ argument therein. To two significant figures, this gives

![]() $R_{\textit{max}}/R_0\sim 0.39\, {\textit{We}}/(1-\cos \vartheta _a)$

, to be compared with

$R_{\textit{max}}/R_0\sim 0.39\, {\textit{We}}/(1-\cos \vartheta _a)$

, to be compared with

![]() $R_{\textit{max}}/R_0\sim 0.47\,{\textit{We}}/(1-\cos \vartheta _a)$

for the RL model. Since the aim of this section is to derive a scaling law with an

$R_{\textit{max}}/R_0\sim 0.47\,{\textit{We}}/(1-\cos \vartheta _a)$

for the RL model. Since the aim of this section is to derive a scaling law with an

![]() $O(1)$

prefactor, the discrepancy between the prefactors here can be considered small. Furthermore, we have compared both models with Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS) (figure 3), and there is good agreement between the DNS and the models, with little to be said in favour of accepting one prefactor over another.

$O(1)$

prefactor, the discrepancy between the prefactors here can be considered small. Furthermore, we have compared both models with Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS) (figure 3), and there is good agreement between the DNS and the models, with little to be said in favour of accepting one prefactor over another.

4. Viscous case

Having completely characterised the inviscid case down to deriving an exact solution for the spreading radius

![]() $R(t)$

, we return to the viscous case, recalled here as (2.18). These equations are valid for phase 1 of the motion, in which the height of the boundary layer is still small compared with the film height

$R(t)$

, we return to the viscous case, recalled here as (2.18). These equations are valid for phase 1 of the motion, in which the height of the boundary layer is still small compared with the film height

![]() $h$

. The aim of this section is to analyse phase 1 of the motion, and also to study phase 2, in which the height of the boundary layer exceeds

$h$

. The aim of this section is to analyse phase 1 of the motion, and also to study phase 2, in which the height of the boundary layer exceeds

![]() $h$

. In this second phase, the form of the (2.18) simplifies drastically.

$h$

. In this second phase, the form of the (2.18) simplifies drastically.

4.1. Recasting of equations for the RL system

We recall (2.18c ) for the momentum

We re-write

We introduce

![]() $\overline {u}=u_0[1-(h_{bl}/h)]$

. Thus, (4.1) becomes

$\overline {u}=u_0[1-(h_{bl}/h)]$

. Thus, (4.1) becomes

\begin{align} V\frac {\mathrm{d} U}{\mathrm{d} t}=2\big (\overline {u}-U\big )^2h+\underbrace {2u_0^2 h_{bl}\left (\!1-\frac {h_{bl}}{h}\right )+\frac {1}{2}\frac {h_{bl} R^2}{(t+t_0)(t+t_1)}}-2\frac {\gamma }{\rho }(1-\cos \vartheta _a). \end{align}

\begin{align} V\frac {\mathrm{d} U}{\mathrm{d} t}=2\big (\overline {u}-U\big )^2h+\underbrace {2u_0^2 h_{bl}\left (\!1-\frac {h_{bl}}{h}\right )+\frac {1}{2}\frac {h_{bl} R^2}{(t+t_0)(t+t_1)}}-2\frac {\gamma }{\rho }(1-\cos \vartheta _a). \end{align}

In a previous work on the analogous 3-D axisymmetric RL model (Bustamante & Ó Náraigh Reference Bustamante and Ó Náraigh2025), a term analogous to the one with the underbrace in (4.3) was omitted, on the basis that it was negligibly small (as justified by Gordillo et al. Reference Gordillo, Riboux and Quintero2019) and also, led to a mathematically tractable set of equations. We follow the same approach here, and we therefore work with a modified momentum equation

where

![]() $c^2=[\gamma /(\rho h)](1-\cos \vartheta _a)$

, and where

$c^2=[\gamma /(\rho h)](1-\cos \vartheta _a)$

, and where

![]() $c$

is the Taylor–Culick speed. Therefore, for the purposes of this section, we examine the following RL model:

$c$

is the Taylor–Culick speed. Therefore, for the purposes of this section, we examine the following RL model:

4.2. Initial conditions

Initial conditions apply at the onset of phase 1. The model has built-in an implied set of initial conditions that give rise to rim generation. At time

![]() $t=R_0/U_0=\tau$

, we take the rim volume to be zero, as in the analogous work on 3-D axisymmetric RL models (Amirfazli et al. Reference Amirfazli, Bustamante, Hu and Ó Náraigh2024; Bustamante & Ó Náraigh Reference Bustamante and Ó Náraigh2025). This gives a natural way to parametrise the rim generation phenomenon, since, by taking

$t=R_0/U_0=\tau$

, we take the rim volume to be zero, as in the analogous work on 3-D axisymmetric RL models (Amirfazli et al. Reference Amirfazli, Bustamante, Hu and Ó Náraigh2024; Bustamante & Ó Náraigh Reference Bustamante and Ó Náraigh2025). This gives a natural way to parametrise the rim generation phenomenon, since, by taking

![]() $V(\tau )=0$

, we obtain (from (4.5c

))

$V(\tau )=0$

, we obtain (from (4.5c

))

Hence

\begin{align} U(t=\tau )=\overline {u}-\sqrt { \frac {\gamma (1-\cos \vartheta _a)}{\rho h}}, \end{align}

\begin{align} U(t=\tau )=\overline {u}-\sqrt { \frac {\gamma (1-\cos \vartheta _a)}{\rho h}}, \end{align}

or

The values

![]() $R_{\textit{init}}$

and

$R_{\textit{init}}$

and

![]() $h_{\textit{init}}$

describe the initial lamella, i.e. just prior to the formation of the rim. For the inviscid case (§ 3), it is important to describe carefully the dependence of these parameters on

$h_{\textit{init}}$

describe the initial lamella, i.e. just prior to the formation of the rim. For the inviscid case (§ 3), it is important to describe carefully the dependence of these parameters on

![]() ${\textit{We}}$

, as this has implications for the value of the prefactor in

${\textit{We}}$

, as this has implications for the value of the prefactor in

![]() $R_{\textit{max}}/R_0\sim {\textit{We}}$

for

$R_{\textit{max}}/R_0\sim {\textit{We}}$

for

![]() ${\textit{We}} \gg 1$

. For the viscous case, this seems less important. For instance, Roisman et al. (Reference Roisman, Rioboo and Tropea2002) determine

${\textit{We}} \gg 1$

. For the viscous case, this seems less important. For instance, Roisman et al. (Reference Roisman, Rioboo and Tropea2002) determine

![]() $R_{\textit{init}}$

and

$R_{\textit{init}}$

and

![]() $h_{\textit{init}}$

using an energy-budget analysis, whereas Eggers et al. (Reference Eggers, Fontelos, Josserand and Zaleski2010) use a geometric argument. In these studies, the final dependence of the spreading radius on

$h_{\textit{init}}$

using an energy-budget analysis, whereas Eggers et al. (Reference Eggers, Fontelos, Josserand and Zaleski2010) use a geometric argument. In these studies, the final dependence of the spreading radius on

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

and

${\textit{Re}}$

and

![]() ${\textit{We}}$

is insensitive to the approach used to set the initial conditions. We use a similar geometric argument to Eggers et al. (Reference Eggers, Fontelos, Josserand and Zaleski2010) here: we assume that the droplet assumes a ‘pancake’ shape at time

${\textit{We}}$

is insensitive to the approach used to set the initial conditions. We use a similar geometric argument to Eggers et al. (Reference Eggers, Fontelos, Josserand and Zaleski2010) here: we assume that the droplet assumes a ‘pancake’ shape at time

![]() $\tau$

, with initial height

$\tau$

, with initial height

![]() $h_{\textit{init}}=R_0/2$

. This gives

$h_{\textit{init}}=R_0/2$

. This gives

![]() $R_{\textit{init}}=V_{\textit{tot}}/(2h_{\textit{init}})$

, where

$R_{\textit{init}}=V_{\textit{tot}}/(2h_{\textit{init}})$

, where

![]() $V_{\textit{tot}}=\pi R_0^2$

is the total (conserved) area.

$V_{\textit{tot}}=\pi R_0^2$

is the total (conserved) area.

4.3. Phase 2 of the motion

In phase 2 of the motion, the boundary layer reaches the height of the lamella. In the present simplified mathematical model, all flow inside the lamella then stops and (2.5) for the interface height reduces to

![]() $\partial h/\partial t=0$

, hence

$\partial h/\partial t=0$

, hence

![]() $h=\text{Const.}$

. We use

$h=\text{Const.}$

. We use

![]() $t_*$

to denote the onset time of phase 2;

$t_*$

to denote the onset time of phase 2;

![]() $t_*$

is obtained from (2.7) by solving

$t_*$

is obtained from (2.7) by solving

Here, we work with the remote asymptotic solution, such that

![]() $f(\boldsymbol{\cdot })=\text{Const.}$

in (2.7). In this case, (4.5) simplify greatly

$f(\boldsymbol{\cdot })=\text{Const.}$

in (2.7). In this case, (4.5) simplify greatly

Equation (4.10) have the simple fixed-point solution

which remains valid until

![]() $R=R(t_*)-c_* t$

touches down to zero (here,

$R=R(t_*)-c_* t$

touches down to zero (here,

![]() $R(t_*)$

is the value of

$R(t_*)$

is the value of

![]() $R(t)$

at the onset of phase 2). Also,

$R(t)$

at the onset of phase 2). Also,

is the Taylor–Culick retraction speed. We note in passing the use of

![]() $c_*$

for a different speed in § 3; we rely on the reader’s judgment to distinguish these, based on the context.

$c_*$

for a different speed in § 3; we rely on the reader’s judgment to distinguish these, based on the context.

The sharp jump between phases 1 and 2 is an artefact of the model, due to the fact that

![]() $\mathrm{d} h/\mathrm{d} t$

changes to zero abruptly in this phase. Thereafter,

$\mathrm{d} h/\mathrm{d} t$

changes to zero abruptly in this phase. Thereafter,

![]() $R(t)$

decreases, meaning that rim retraction begins immediately in phase 2, if it is has not done so already in phase 1. Nevertheless, phase 2 of the model does capture accurately the competing effects of intertia and surface tension in rim retraction. Indeed, (4.10) is identical in form to the model put forward by Taylor (Reference Taylor1959) to describe the retraction of a liquid sheet (once the necessary changes in the problem set-up have been accomplished). The more realistic radially symmetric version of the model is also presented in the work by Taylor (Reference Taylor1959), and by Culick (Reference Culick1960). An exact solution of the radially symmetric model is presented by Bustamante & Ó Náraigh (Reference Bustamante and Ó Náraigh2025).

$R(t)$

decreases, meaning that rim retraction begins immediately in phase 2, if it is has not done so already in phase 1. Nevertheless, phase 2 of the model does capture accurately the competing effects of intertia and surface tension in rim retraction. Indeed, (4.10) is identical in form to the model put forward by Taylor (Reference Taylor1959) to describe the retraction of a liquid sheet (once the necessary changes in the problem set-up have been accomplished). The more realistic radially symmetric version of the model is also presented in the work by Taylor (Reference Taylor1959), and by Culick (Reference Culick1960). An exact solution of the radially symmetric model is presented by Bustamante & Ó Náraigh (Reference Bustamante and Ó Náraigh2025).

4.4. Analysis of the equations of motion using inequalities

Unlike in the inviscid case, the viscous RL model (4.5) does not admit an exact solution. However, we can characterise the solution using differential inequalities, similar to what was done in the 3-D axisymmetric case by Bustamante & Ó Náraigh (Reference Bustamante and Ó Náraigh2025). We summarise the approach here, and refer the interested reader to Appendix C for the lengthy calculations which underpin this summary. We start with the velocity defect

Hence, (4.1) become

By direct computation, we get

\begin{align} \frac {\mathrm{d}\Delta }{\mathrm{d} t}+\frac {\varDelta }{t+t_0}\left (1-\frac {h_{bl}}{h}\right )= -2 (\varDelta ^2-c^2 )(h/V)-\frac {u_0}{t+t_0}\frac {h_{bl}}{h}\underbrace {\left [{1-\frac {h_{bl}}{h}}+\frac {1}{2}\frac {t+t_0}{t+t_1}\right ]}_{=\varPhi (t)\geq 0}\!. \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\mathrm{d}\Delta }{\mathrm{d} t}+\frac {\varDelta }{t+t_0}\left (1-\frac {h_{bl}}{h}\right )= -2 (\varDelta ^2-c^2 )(h/V)-\frac {u_0}{t+t_0}\frac {h_{bl}}{h}\underbrace {\left [{1-\frac {h_{bl}}{h}}+\frac {1}{2}\frac {t+t_0}{t+t_1}\right ]}_{=\varPhi (t)\geq 0}\!. \end{align}

Since each term on the right-hand side is now of definite sign, we can conclude

The appearance here of a differential inequality linear in

![]() $\varDelta$

enables us to apply Gronwall’s inequality. We apply this inequality to (4.16) with

$\varDelta$

enables us to apply Gronwall’s inequality. We apply this inequality to (4.16) with

![]() $V(t=\tau )=0$

to obtain

$V(t=\tau )=0$

to obtain

where

The full details of this calculation are provided in Appendix C. We use

![]() $\varDelta =[R/(t+t_0)] [1-(h_{bl}/h)]-(\mathrm{d} R/\mathrm{d} t)$

to re-write inequality (4.17) as

$\varDelta =[R/(t+t_0)] [1-(h_{bl}/h)]-(\mathrm{d} R/\mathrm{d} t)$

to re-write inequality (4.17) as

This can be re-written as

We note that

![]() $V=V_{\textit{tot}}-2\textit{Rh}$

and identify

$V=V_{\textit{tot}}-2\textit{Rh}$

and identify

![]() $\eta = \textit{Rh}$

. Hence, we re-write inequality (4.20) as

$\eta = \textit{Rh}$

. Hence, we re-write inequality (4.20) as

This can be solved to give

\begin{align} V_{\textit{tot}}\eta -\eta ^2\geq V_{\textit{tot}}\eta _{\textit{init}}-\eta _{\textit{init}}^2 -(\gamma /\rho )(1-\cos \vartheta _a)\underbrace {\left [2\int _\tau ^t h^2 I_h(t)\mathrm{d} t\right ]}_{=\Delta G(t)} \! . \end{align}

\begin{align} V_{\textit{tot}}\eta -\eta ^2\geq V_{\textit{tot}}\eta _{\textit{init}}-\eta _{\textit{init}}^2 -(\gamma /\rho )(1-\cos \vartheta _a)\underbrace {\left [2\int _\tau ^t h^2 I_h(t)\mathrm{d} t\right ]}_{=\Delta G(t)} \! . \end{align}

Inequality (4.22) is a quadratic inequality. Critical points occur at

![]() $\eta _{\textit{cr},\pm }(t)$

, where

$\eta _{\textit{cr},\pm }(t)$

, where

(we write

![]() $\eta _{\textit{cr},\pm }(t)$

to indicate that the critical points are time-dependent). Since

$\eta _{\textit{cr},\pm }(t)$

to indicate that the critical points are time-dependent). Since

![]() $\eta (t)=R(t)h(t)$

, we have

$\eta (t)=R(t)h(t)$

, we have

![]() $R(t)h(t)\leq \eta _{\textit{cr},+}(t)$

. Similarly, with the negative sign chosen, we get

$R(t)h(t)\leq \eta _{\textit{cr},+}(t)$

. Similarly, with the negative sign chosen, we get

![]() $R(t)h(t)\geq \eta _{\textit{cr},-}(t)$

. Since this is true for all

$R(t)h(t)\geq \eta _{\textit{cr},-}(t)$

. Since this is true for all

![]() $t$

, we must have

$t$

, we must have

![]() $R(t_*)h(t_*)\geq \eta _{\textit{cr},-}(t_*)$

, hence

$R(t_*)h(t_*)\geq \eta _{\textit{cr},-}(t_*)$

, hence

\begin{align} R(t_*)\geq \frac {\eta _{\textit{cr}-}(t_*)}{h(t_*)}\mathop {=}\limits ^{\text{(4.23)}} \frac {1}{2}\frac {V_{\textit{tot}}}{h(t_*)}-\underbrace { [(\gamma /\rho )(1-\cos \vartheta _a)]^{1/2}\frac {[\Delta G(t_*)]^{1/2}}{h(t_*)}}. \end{align}

\begin{align} R(t_*)\geq \frac {\eta _{\textit{cr}-}(t_*)}{h(t_*)}\mathop {=}\limits ^{\text{(4.23)}} \frac {1}{2}\frac {V_{\textit{tot}}}{h(t_*)}-\underbrace { [(\gamma /\rho )(1-\cos \vartheta _a)]^{1/2}\frac {[\Delta G(t_*)]^{1/2}}{h(t_*)}}. \end{align}

We apply the following observations to inequality (4.24):

-

(i) since the term with the underbrace is proportional to

$\gamma ^{1/2}$

, and

$\gamma ^{1/2}$

, and

$\gamma \propto {\textit{We}}^{-1}$

, the right-hand side of the inequality is positive, for sufficiently large

$\gamma \propto {\textit{We}}^{-1}$

, the right-hand side of the inequality is positive, for sufficiently large

${\textit{We}}$

;

${\textit{We}}$

; -

(ii) by definition, we have

$\max _t R(t)\geq R(t_*)$

. Here, the maximum

$\max _t R(t)\geq R(t_*)$

. Here, the maximum

$\max _t ({\cdots} )$

is taken over all times for which the RL model applies (

$\max _t ({\cdots} )$

is taken over all times for which the RL model applies (

$t\geq \tau$

).

$t\geq \tau$

).

Putting these observations together, we have

Here, the last inequality is true for

![]() ${\textit{We}}$

sufficiently large; without this, the string of inequalities would be vacuous.

${\textit{We}}$

sufficiently large; without this, the string of inequalities would be vacuous.

For an upper bound, we reuse the argument due to Bustamante & Ó Náraigh (Reference Bustamante and Ó Náraigh2025). We have

Hence,

If the maximum occurs in phase 1, then

![]() $h(t)$

is monotone decreasing, hence

$h(t)$

is monotone decreasing, hence

![]() $h(t_{\textit{max}})\geq h_*$

, hence

$h(t_{\textit{max}})\geq h_*$

, hence

![]() $1/h(t_{\textit{max}})\leq 1/h_*$

and

$1/h(t_{\textit{max}})\leq 1/h_*$

and

If the maximum occurs in phase 2, then

![]() $h(t)$

is a constant function and equal to

$h(t)$

is a constant function and equal to

![]() $h_*$

, so it is still the case that

$h_*$

, so it is still the case that

![]() $R_{\textit{max}}\leq V_{\textit{tot}}/(2h_*)$

. Hence, in both cases, inequality (4.28) is true. Hence, by a sandwich result, we have

$R_{\textit{max}}\leq V_{\textit{tot}}/(2h_*)$

. Hence, in both cases, inequality (4.28) is true. Hence, by a sandwich result, we have

4.5. Evaluation of the bounds

To make further progress, we study

![]() $h_*$

in more detail, to extract its

$h_*$

in more detail, to extract its

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

-dependence. For this purpose, we solve (2.6) numerically. We assume the remote asymptotic approximation such that

${\textit{Re}}$

-dependence. For this purpose, we solve (2.6) numerically. We assume the remote asymptotic approximation such that

![]() $h(x,t)$

no longer depends on space, and such that (2.6) becomes an ODE, specifically

$h(x,t)$

no longer depends on space, and such that (2.6) becomes an ODE, specifically

(as we are using the remote asymptotic approximation, the inequality

![]() $\tau \ll t$

is applied here). As per the previous discussion in this section, we use the initial condition

$\tau \ll t$

is applied here). As per the previous discussion in this section, we use the initial condition

![]() $h(\tau )=R_0/2$

. Equation (4.30) can be solved explicitly; however, it is just as straightforward to solve it numerically in Matlab. We use the stiff solver ode15s, which readily handles the transition which occurs when

$h(\tau )=R_0/2$

. Equation (4.30) can be solved explicitly; however, it is just as straightforward to solve it numerically in Matlab. We use the stiff solver ode15s, which readily handles the transition which occurs when

![]() $\mathrm{d} h/\mathrm{d} t$

jumps abruptly to zero at

$\mathrm{d} h/\mathrm{d} t$

jumps abruptly to zero at

![]() $t=t_*$

. We furthermore solve (4.30) using dimensionless variables, such that all length scales are normalised by

$t=t_*$

. We furthermore solve (4.30) using dimensionless variables, such that all length scales are normalised by

![]() $R_0$

, and all velocity scales by

$R_0$

, and all velocity scales by

![]() $U_0$

. The fluid density

$U_0$

. The fluid density

![]() $\rho$

sets the scale for mass. Equation (4.30) can then be non-dimensionalised by formally replacing

$\rho$

sets the scale for mass. Equation (4.30) can then be non-dimensionalised by formally replacing

![]() $\nu$

by

$\nu$

by

![]() ${\textit{Re}}^{-1}$

, and by implicitly taking

${\textit{Re}}^{-1}$

, and by implicitly taking

![]() $h\rightarrow h/R_0$

,

$h\rightarrow h/R_0$

,

![]() $t\rightarrow t U_0/R_0$

and similarly for