I. Introduction

In business and human rights (BHR) scholarship, a legal waiver refers to a clause within a settlement agreement that facilitates compensation to rightholders in exchange for relinquishing the right to pursue future claims, typically civil claims, arising from a human rights dispute with a corporation. Legal waivers serve two functions. First, legal waivers provide finality and predictability to future claims by confirming a full and final settlement, including the waiver of any further rights or actions related to the same subject matter.Footnote 1 Second, they prevent double recovery.Footnote 2 Double recovery refers to instances where a claimant seeks multiple compensations for the same grievance. It can be argued that the normative basis of waivers aligns closely with Ruggie’s approach to the drafting of United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs):Footnote 3 a principled form of pragmatism.Footnote 4 Principled pragmatism involves leveraging corporate engagement as a means of addressing complex human rights challenges with ‘practical results’.Footnote 5 Such an approach encourages companies to integrate human rights considerations into their policy frameworks and daily operations as a strategic and operational priority leading to ‘practical action paths’.Footnote 6

It is not unfounded that without waivers, companies may risk facing repeated legal challenges regarding compensation, which could disrupt operations and lead to financial losses. Alternatively, legal waivers come with the risk of corporations being seen as using them to limit rightholders access to judicial remedies as well as a measure to limit exposure to potential legal liability.Footnote 7 However, legal waivers are not mere procedural instruments that stem potential claims. They carry substantive legal implications, shaping the contours of corporate accountability and rightholders’ access to remedy.

The use of legal waivers was witnessed in the Porgera gold mine settlement in Papua New Guinea, where 119 Indigenous women, who had suffered sexual violence by the mine’s security personnel, were required to sign legal waivers in order to receive individual benefits.Footnote 8 In many instances, the women did not fully understand the consequences of signing legal waivers.Footnote 9 The case was eventually settled out of court, but the final settlement amount was not disclosed publicly. It was an instance that sheds light on how legal waivers hinder access to remedies for vulnerable rightholders.

Understanding legal waivers is relevant as they are currently presented as a neutral tool that gives a choice mitigating the probability of resorting to future claims or jeopardising access to remedies. This creates a false dilemma that pits corporate survivability against corporate accountability. It is further bolstered by the overarching design of nonjudicial mechanisms that presents waivers as part of the ‘take-it or leave-it’Footnote 10 settlement agreement. Such a binary framing fails to interrogate the systemic power asymmetries that shape settlement processes. For the purposes of this article, the analysis is confined to legal waivers used in operational-level grievance mechanisms, where rightholders and corporations enter into settlement agreements.

Against this backdrop, complex legal and ethical questions arise. Can waivers be ‘legitimately’Footnote 11 included in settlements, especially in BHR cases, concerning adverse human rights impact irrespective of the harm caused? Should waiver clauses be permitted where there is a demonstrable power imbalance between the parties? Should legal waivers be the default tool irrespective of the nature and context of harm? With few exceptions,Footnote 12 existing scholarship largely concentrates on the design and efficacy of non-judicial grievance mechanisms.Footnote 13 International law guidance on legal waivers suggests its limited use in resolving BHR disputes.Footnote 14 The basis of restricting their use is that legal waivers may conflict with the commentary to Principle 29 of the UNGPs, which emphasises that grievance mechanisms must not preclude access to judicial or other nonjudicial grievance mechanisms.Footnote 15 Drawing from this, I contend that there is an emerging need for legal waivers to be governed by stricter substantive standards and subject to greater transparency.

This article will grapple with three fundamental questions. First, why is the current framework of the UNGPs unable to establish legal standards for waivers? Second, what is the need for legal waivers in BHR cases? Third, how does confidentiality hinder the development of comprehensive legal standards governing waivers in BHR disputes? These three questions are interconnected, as each underscores how the absence of clear legal standards has created a grey zone, enabling corporations to draft waivers with limited independent oversight irrespective of associated contextual factors. Taken together, these three lines of inquiry, on need, status and structural opacity of legal waivers address significant gaps in the BHR literature that must be attended to.

The article is structured in five parts. Following this introduction, Part II examines why the current framing of the UNGPs is insufficient to address legal waivers. It shows how the UNGPs’ procedural formalism, combined with the post-hoc corporate justification of waivers as practical tools, creates a grey zone exacerbating existing inequality of bargaining power. Part III analyses the financial dynamics of settlement agreements, arguing that corporations deploy waivers to contain litigation risks in the face of volatile and potentially prohibitive costs. Part IV turns to confidentiality, demonstrating how non-disclosure of settlement terms entrenches opacity, reinforces corporate informational advantage and obstructs the development of legal standards on waivers. It introduces a hybrid regulatory model anchored in a differentiated disclosure regime that operationalises transparency and strengthens corporate accountability for settlement of human rights disputes as a response to confidentiality. Part V concludes that legal waivers are not neutral contractual devices but structural instruments that limit rightholders’ claims and insulate corporations from accountability.

II. Procedural Formalism and Justifying Legal Waivers

The incorporation of non-state-based grievance mechanisms into the UNGPs marked a significant evolution in access to nonjudicial remedies within the BHR framework.Footnote 16 A common observation within BHR scholarship is that remedies have remained ‘rare’Footnote 17 and that Pillar III, i.e., the access to remedy pillar of the UNGP, is a ‘forgotten pillar’.Footnote 18 Organisations such as the International Commission of JuristsFootnote 19 and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)Footnote 20 have issued reports to strengthen the implementation of access to remedy. These reports became the point of departure for a critical examination of non-state-based grievance mechanisms. But these reports did not discuss legal waivers at length. OHCHR has reaffirmed that effective grievance mechanisms must not require individuals to waive their right to pursue remedies through alternative grievance mechanisms, whether state-based or non-state-based, as a condition for access or participation.Footnote 21

I contend that there are two pointers that highlight the current limitations regarding legal waivers. First, the procedural focus of the UNGPs on the design and effectiveness of grievance mechanisms, and second, the corporate justification of legal waivers as practical measures. As discussed below, these two factors together highlight the inherent power imbalance between rightsholders and corporations in private, company-led processes.

There has been an emphasis on crafting ‘effective’ grievance mechanisms under Principle 31 of the UNGPs than on wider substantive minimum human rights standards for remedies. The larger debate on how we can hold corporations accountable under international lawFootnote 22 transformed into how we can ‘design’Footnote 23 effective grievance mechanisms. Scholarly attention also gravitated towards discussions surrounding the effectiveness of grievance mechanisms in seeking redress.Footnote 24 Through generating effective alternative avenues to resolve disputes, the fundamental question of corporate accountability under international law took a backseat. This shift has been criticised as ‘elevation of forum over substance’.Footnote 25 Owing to this shift, corporations retain significant discretion in defining what constitutes effective remedies, especially for remedies obtained from nonjudicial processes.Footnote 26

To fill the vacuum of substantive minimum human rights standards for remedies, the United Nations Working Group on BHR defined effective remedies as remedies that are ‘rightsholders-oriented’.Footnote 27 This approach is characterised by positioning ‘human solidarity’ with ‘victims of violations of international law’Footnote 28 as the central tenet of remedies. The Working Group articulated guidance delineating the constituent elements of effective remedies. An effective remedy:

-

• is free from fear of victimisation,

-

• requires a bouquet of remedies,

-

• provided through judicial or nonjudicial remedial mechanisms should not treat rightsholders merely as recipients of remedy,

-

• should be judged from the perspective of affected rightsholders,

-

• should address the existing power imbalance between the affected rightsholders and given enterprise-facing allegations of human rights abuses,

-

• is available without discrimination,

-

• is sensitive to the diverse experiences of victims,

-

• is accessible, affordable, adequate and timely and

-

• requires that rightsholders have access to information about their rights, the duties of states and the responsibilities of businesses concerning those rights.Footnote 29

Despite the above guidance on effective remedies, legal waivers continue to be problematic and have remained a thorny issue for BHR experts with ‘acute’ concerns given significant power disparity.Footnote 30

Moreover, legal waivers are seen as practical measures that prioritise predictability of litigation over securing substantive justice. When the late Professor John Ruggie, who had drafted the UNGPs, was asked about his opinion on legal waivers, he indicated that doing away with waivers is an unlikely event.Footnote 31 This position was also echoed in OHCHR’s advisory, which clarified that there is no international legal prohibition on the use of legal waivers for civil suits.Footnote 32 The OHCHR issued a non-legally binding opinion on the inclusion of legal waivers in Barrick’s settlement agreement in the Porgera case. The opinion stated that:

the presumption should be that as far as possible, no waiver should be imposed on any claims settled through a non-judicial grievance mechanism. Nonetheless, and as there is no prohibition per se on legal waivers in current international standards and practice, situations may arise where business enterprises wish to ensure that, for reasons of predictability and finality, a legal waiver be required from claimants at the end of a remediation process.Footnote 33

The OHCHR position analogised using legal waivers to reparations programs driven by states in post-conflict states.Footnote 34 The opinion focused on the fact that ‘contextual factors play a significant role’Footnote 35 in determining how grievance mechanisms are designed.Footnote 36 Moreover, OHCHR suggested that there is ‘no consistent practice or jurisprudence from regional and national courts on this issue’.Footnote 37 Scholarly opinion on legal waivers also followed OHCHR’s advice, but with some caveats. Some scholars have urged ‘a very strong presumption against’Footnote 38 the use of legal waivers, especially for serious corporate human rights abuses.Footnote 39 Others argue that waivers must be used only when there is a ‘clear demonstration of equality of arms, fully informed claimant consent and provision of comprehensive legal advice, and strict compliance with human rights principles and the effectiveness criteria’.Footnote 40 Experts have also challenged the acceptability of waivers, citing that waivers are only assessed on grounds of rights-compatibility without considering Principle 31 of the UNGPs as a whole.Footnote 41 However, a point of consensus seems to have emerged that suggests that legal waivers need to be constructed ‘narrowly’.Footnote 42 Yet, even the most narrowly constructed waivers must still meet the underlying corporate objective of precluding future claims against the company.

The procedural emphasis of the UNGPs on the design and effectiveness of grievance mechanisms, combined with the normative post-hoc business justification of legal waivers as a practical tool, reveals the inherent power imbalance between rightholders and corporations in operational-level grievance mechanisms. There is a disconnect between the intent of the UNGPs (substantive justice and reparations) and the actual implementation of nonjudicial grievance mechanisms (focused on process and conflict management).Footnote 43 Remedies arrived at without a ‘participatory parity’Footnote 44 of the rightholders risks allowing power imbalances to skew the outcomes against the marginalised. Given the power imbalance between rightsholders and corporations, issues such as legal waivers are often reduced to technical minutiae, falling outside the scope of meaningful scrutiny. Rightholders, often operating with limited legal support, under financial duress, or in contexts of institutional and informational disadvantage, may feel compelled to accept waivers as the only viable pathway to any form of remedy.Footnote 45 This tension is most clearly illustrated by examining one of the key drivers why corporations push for waivers: the cost of settlements.

III. Corporate ‘Settlement Mill’Footnote 46

Settlements of claims can arise in various contexts. Some settlements are reached after litigation has been initiated but before adjudication is complete; others occur post-adjudication after determination of liability. In some instances, settlements result from direct negotiations between the parties prior to any formal legal proceedings. The settlements that are achieved from direct negotiations reflect a market function where the ‘individual rights of harmed become secondary to the market efficiencies’.Footnote 47 These settlements are not necessarily justice-oriented but instead serve the instrumental purpose of resolving grievances quickly. However, publicly available data on settlement reached because of direct negotiations for BHR linked disputes remains limited. This opacity presents a significant obstacle to confidentiality for BHR research in the coming decade (discussed in the next part). In the absence of publicly available data, meaningful insight can nonetheless be derived through an analysis of publicly disclosed settlements involving corporate-human rights violations. While these figures are not reflective of outcomes reached via direct negotiations, they serve to approximate the scale of financial liability borne by corporations and underscore patterns of monetary redress in well-known cases of corporate wrongdoing.

Existing scholarship suggests that only a small number of cases are settled.Footnote 48 In a 2012 study, a selection of 36 tort-based cases revealed that settlements were achieved only in around 6 cases.Footnote 49 Furthermore, dismissal of claims against companies has become common, especially when litigated in courts.Footnote 50 The Business and Human Rights Resource Centre’s (BHRRC) global lawsuit database tracker shows that most cases against corporations were closed or dismissed.Footnote 51 The number of cases that were dismissed was higher than those settled.Footnote 52 Even though settlements are rare and dismissals of cases against corporations high, some cases can put both parties in a ‘lose-lose situation’.Footnote 53

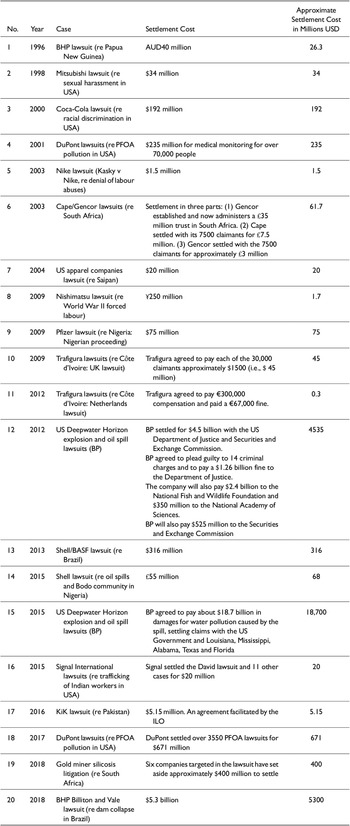

An empirical review of 151 cases (1994–2018) in the BHRRC database, published in the Good Business report, shows that settlements can impose significant financial burdens on corporations, in some instances amounting to billions of dollars.Footnote 54 Table 1 presents the financial costs incurred by defendant companies to settle cases between 1996 and 2018, including only settlements where the amounts were publicly disclosed.Footnote 55 These cases span a wide range of claims, including environmental damage, employment discrimination, labour rights violations and transnational tort litigation. While such a comparative analysis, spanning different categories of human rights violations and instances beyond direct negotiations, is not conclusive, it is methodologically justified in light of the structural similarities in the harms addressed and the corporate actors involved. For analytical consistency, all monetary values were converted into approximate United States dollars using indicative historical exchange rates at the time of settlement. This allowed for meaningful comparison across different legal systems and currencies.

Table 1. Sample Costs of Out-of-Court SettlementFootnote 56

A closer scrutiny of the sample reveals a small number of exceptionally high-value settlements. These include BP’s Deepwater Horizon settlements in 2012 and 2015, as well as the 2018 settlement arising from the BHP and Vale dam collapse in Brazil. Graph 1 converts the table into a visualisation and shows the standardised data on 20 major settlements between 1996 and 2018 (minus the 3 exceptionally high settlements). This is done to see whether there is a generalisable pattern in year-on-year settlement costs.

Graph 1. Approximate Settlement Cost in Millions USD.

When the big settlement outliers are excluded, a more stable pattern emerges. Most settlements fall within a range of US$20 million to US$300 million. Smaller-scale settlements continue to appear throughout, even post-2010. This suggests that high-profile disasters attract exceptionally large payouts, but that is the case in minority of cases. The observed increases are case-specific, often influenced by a wide array of factors including the severity of harm, media attention, legal complexity, jurisdiction or the political and reputational pressures facing the defendant. Considering the financial implications of settlements on corporations, settlements can become a costly affair.

It will be incorrect to assume that all BHR lawsuits worldwide result in high-value settlements. Settlement rates vary markedly across jurisdictions. Existing research highlights that common law systems such as the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia display significantly higher rates of settlement than civil law countries, particularly those influenced by the French legal tradition.Footnote 57 Several factors account for this divergence. Legal origin, case type and procedural rules play a decisive role. Mechanisms such as early evidence disclosure and the pace of court proceedings affect the likelihood of settlement.Footnote 58 Settlement rates are higher in tort actions, especially in the United States.Footnote 59

In this context, legal waivers operate as a tool for cost management. Where settlements are substantial, legal waivers function to bar further litigation, thereby providing finality. Even where settlement amounts are more modest, legal waivers serve to minimise the diversion of corporate resources and reinforce closure of the dispute. Corporations are thus overall incentivised to employ them as a means of foreclosing future proceedings.

IV. Confidentiality

Confidentiality manifests in BHR settlements in different ways. These include confidentiality over the terms of settlement agreements, nontransparent grievance processes and the protection of rightholders’ identities. For the purposes of this article, the focus will be on one of the most significant challenges to public accountability: confidentiality over the terms of settlement agreements. When rightholders accept settlements that contain legal waiver clauses, confidentiality provisions imposed by corporations often prevent public scrutiny of these agreements. This raises critical concerns about compatibility of the practice of confidentiality by corporations with the transparency requirement embedded in the UNGPs. Specifically, Principle 31(e) of the UNGPs, which outlines transparency in grievance mechanisms, is limited to defining transparency as keeping parties informed about the development and operation of grievance mechanisms.Footnote 60 This limited definition creates a normative gap that arguably legitimises corporate reliance on confidential settlements including legal waivers, thus undermining the effectiveness of these mechanisms. It also raises a fundamental question: can remedial outcomes secured through grievance mechanisms with confidential terms and conditions be reconciled with the right to an effective remedy under Pillar III?Footnote 61

A particularly illustrative case about confidentiality of terms emerged when civil society organisations challenged African Barrick Gold (subsequently renamed Acacia Mining) regarding their implementation of legal waivers in North Mara, Tanzania.Footnote 62 The company articulated three principal justifications for maintaining confidentiality in settlement agreements containing legal waivers. First, the company argued that ‘providing information about specific grievances to the public at large’Footnote 63 does not align with the definition of transparency under the UNGPs. Second, the company added that fear for the women’s safety, who could be affected by disclosing the amount received as compensation in exchange for legal waivers, might create ‘heightened concerns about abuse and re-victimization of the women’.Footnote 64 The company claimed that rightholders ‘have asked that that fact not be publicized because they fear for their own safety from members of the community seeking to appropriate their remediation benefits’.Footnote 65 The company further argued that it was because ‘revealing levels of financial compensation would compromise individuals and legitimate processes’.Footnote 66 The company also claimed that confidentiality provided a ‘safe space for engagement’, ‘protected the privacy of users’ and ‘prevented reprisals’.Footnote 67 Third, ‘local views and preferences’ and the ‘needs of vulnerable populations’ made a case to favour confidentiality.Footnote 68 Based on these reasons, the company assumed the agreement’s confidentiality to be a ‘consensually agreed norm’.Footnote 69 The company, however, revised the agreement and later made confidentiality of the agreement optional in 2014, as it accepted the criticism that its confidentiality requirement was ‘unnecessarily strict’.Footnote 70 Whereas the confidentiality provision was revised, the company decided to ‘continue to honour the confidentiality provision’ and said that it would ‘not object if complainants choose to share their Grievance Resolution Agreements’Footnote 71 even when someone has accepted the confidentiality provision.

Another relevant case concerning the use of legal waiver is that of the Solai Dam burst in Kenya.Footnote 72 In this case, local media in Kenya reported that ‘a small group of people were asked to sign waivers and received compensation in a way that seemed inappropriate’.Footnote 73 When the rightholders decided to sue the government and the dam operator for infringement of their constitutional rights, the use of waiver was also reported by other media outlets.Footnote 74 The use of waiver and its role in providing remedies was later detailed in a report by the Working Group, where waivers tantamounted to ‘obstruction of access to an effective remedy for victims’.Footnote 75 The report highlighted that

During its visit in situ, the Working Group met with members of affected communities and was concerned to hear that during a meeting convened by some company managers with the presence of local authorities, cheques had been handed to people who had lost family members, housing and/or business, in exchange for their signing an indemnity form that would absolve the company of any responsibility for the disaster. This could amount to an obstruction of access to an effective remedy for victims.Footnote 76

Unlike the Porgera and North Mara cases, the Solai Dam case did not generate the same debate in the BHR field, possibly because it has limited public information for informed analysis. The case was recently reported to have settled out of court at 57 million Kenyan Shillings (US$441,000).Footnote 77

Confidentiality has an adverse impact on rightholders. First, confidentiality over terms, including that of legal waivers, risks creating an information asymmetry where corporations maintain detailed records of settlements while affected communities are put in a ‘take-it or leave-it’ position.Footnote 78 This information asymmetry fundamentally undermines the ability of rightholders to seek higher settlements. Second, confidentiality of terms, including legal waivers, limits the opportunities for developing solidarity amongst different groups of rightholders who are involved in the settlement. The lack of free flow of information within rightholders’ communities may stem the development of community resistance against accepting whatever compensation is awarded. Third, confidential settlements in the BHR field do not contribute to the development of legal precedent. The absence of a public judgment diminishes the potential deterrent effect on future misconduct and reduces the chance for structural change. By embedding waivers within routine contractual settlement agreements, corporations can effectively insulate themselves from legal and reputational consequences. This opaqueness is particularly problematic in jurisdictions with weak regulatory oversight, where rightholders may have limited access to independent legal advice or alternative avenues for redress.

I advance the argument that two key principles may assist in recalibrating the relationship to address the issue of confidentiality over terms in BHR settlements. First, a pragmatic solution to the challenge of confidentiality in settlement agreements is to differentiate between commercial terms (e.g., settlement amounts) and rights-affecting terms (e.g., concessions by rightholders). By categorising various clauses in a settlement agreement, we can better calibrate the extent of disclosure needed without entirely compromising legitimate business interests. Such a framework avoids the reductive all-or-nothing transparency approach. I term this a differentiated disclosure regime. It attempts to balance rightholders’ informational needs and decisional autonomy while securing corporate interests. The concept of differentiated disclosure derives from legal design theory in consumer law scholarship.Footnote 79 It rejects the prevailing ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to contractual transparency.Footnote 80

The bifurcation between commercial and rights-affecting terms must rest on clear, justiciable standards. Otherwise, there may be a risk of corporations using the cover of commercial terms to not disclose rights-affecting terms. The primary standard should be public interest. Commercial terms such as settlement amounts typically concern the private economic arrangements between parties. While not irrelevant to public accountability, their confidentiality does not fundamentally undermine the effectiveness of grievance mechanisms under Principle 31 of the UNGPs. By contrast, rights-affecting terms engage broader public interests. These include waivers of future legal claims, non-disparagement clauses, confidentiality provisions that prevent disclosure of harmful corporate practices, and indemnification clauses that shift legal liability. These provisions shape rightholders’ ongoing legal capacities and their ability to participate in public discourse about corporate accountability.

Secondly, courts must subject settlement agreements to substantive scrutiny under domestic legal systems, especially those accompanying legal waivers. This principle addresses a critical gap in current practice. Courts often treat confidentiality provisions as presumptively enforceable absent extraordinary circumstances. By subjecting legal waivers to greater local scrutiny, domestic courts can develop further specific standards for BHR settlements. The legal basis for such scrutiny already exists in various forms across jurisdictions. For instance, in Papua New Guinea, the Fairness of Transaction Act 1993 in PNG serves as the primary legal framework that can scrutinise legal waivers in settlement agreements used by Barrick Gold.Footnote 81 The Act includes provisions that regulate conduct between two parties in unequal bargaining positions. Moreover, the Act emphasises the role of the state in reviewing unfair contractual obligations as part of remedial processes. However, such application of domestic contract law to legal waivers has not been examined in BHR scholarship.

These two principles together point towards a possibility of a hybrid regulatory model for settlement of human rights claims: one that advocates for scaffolded disclosure of settlement terms while allowing for contextual flexibility. The hybrid model would operate on two levels. At the foundational level, it would establish bright-line prohibitions against certain categories of provisions. These include waivers that extend to criminal claims, non-disparagement clauses or sharing of information about personal harm suffered with others and indemnification clauses that shift liability for indirect breaches to rightholders. These core prohibitions would be non-waivable. They would apply regardless of the parties’ consent. This recognises that severe inequality of bargaining power undermines the voluntariness of settlement agreement. At the second level, the hybrid model would incorporate contextual factors that influence the permissibility and enforceability of other settlement terms. Key contextual considerations would include: the relative sophistication and resources of the parties, whether rightsholders had access to independent legal advice and whether the settlement provides for ongoing remediation. This contextual layer acknowledges that not all power imbalances are equally severe. It recognises that some corporate confidentiality interests may be legitimate. For instance, information protected as trade secrets may remain confidential when disclosure would compromise legitimate commercial interests. By combining core protections with contextual flexibility, this hybrid model recognises that inequality of bargaining power is not a binary condition but exists on a spectrum.

V. Conclusion

This article has shown that the procedural formalism of the UNGPs, the prohibitive cost of settlements, and the opacity surrounding settlement terms collectively enable corporations to use legal waivers as shields against future accountability. The absence of standardised frameworks governing legal waivers introduces significant risks to achieving remedies that are ‘authentically dialogic … morally expansive [and] victim centric’.Footnote 82 The debate over legal waivers has too often been framed in binary terms: should they be permitted or prohibited? This dichotomy is unproductive.

A more constructive way forward lies in the development of a differentiated disclosure regime coupled with domestic legal scrutiny. Such a framework would reject blanket confidentiality, distinguish between commercial terms and rights-affecting terms and mandate disclosure where public interest demands it. In parallel, domestic courts should subject settlement agreements containing waivers to substantive review, ensuring that freedom to contract does not validate provisions that undermine access to remedy.

Taken together, these principles point towards a hybrid regulatory model: one that establishes bright-line prohibitions against the most harmful practices (such as waivers of criminal liability, non-disparagement clauses, or indemnification of corporate wrongdoing), while allowing contextual flexibility for less harmful provisions. The differentiated disclosure framework is therefore not a cosmetic adjustment but a structural recalibration of how confidentiality and waivers operate in BHR settlements. It ensures that confidentiality serves its protective function without eroding accountability. Unless such reforms are pursued, legal waivers risk entrenching a system in which corporate accountability is sacrificed for efficiency. The stakes for the credibility of the BHR framework, and for the right to effective remedy under Pillar III, could not be higher.