On Ash Wednesday 1387 Grand Duke Jogaila of Lithuania – newly crowned king of Poland and bearing his new polonised Christian name of Władysław Jagiełło – arrived in his capital city of Vilnius. At the time, Vilnius was the capital of a vast polity forged by the Lithuanians from the twelfth century onwards, which reached from the Baltic Sea to the territory of the Crimean Tatars at the edge of the Black Sea; the Grand Duchy of Lithuania took in today’s Belarus, parts of Ukraine, and some of what is now western Russia. Fourteenth-century Vilnius was a multi-religious city; there were already Orthodox and Catholic churches there and a Franciscan friary. There may even have been small communities of Jews and Muslim Tatars. But at the heart of the city stood a roofless building, unlike any other in a European capital city. Built as a cathedral over a century earlier, it was now sacred to Perkūnas, the god of thunder, and open to the skies. Six fires burned before a six-sided altar, representing the cycle of the year, where goats were sacrificed to the thunder god.Footnote 1 On a hill above the city burned a perpetual fire, attended by a vaidila (priest) who divined the future by gazing into the flames.Footnote 2 Sacred forests, where it was forbidden to fell a tree or hunt animals, surrounded the city, and at the confluence of the Rivers Neris and Vilnia was a sacred site dedicated to the cremation of the mighty dead.

Jogaila laboured for days to convince his people to embrace the Catholic Christian faith. It was no easy task; the Lithuanians had been at war with the Teutonic Knights, a crusading missionary order, for the past century and a half. Refusal to embrace one of the proselytising monotheistic faiths – Latin Catholicism, Greek Orthodox Christianity, or Islam – had become a defining feature of Lithuanian identity. Furthermore, Jogaila’s Polish priests had no knowledge of the Lithuanian language and the king himself had to act as translator. However, Jogaila had brought woollen robes which he offered as a gift to anyone who accepted baptism, and eventually the Lithuanians consented to be baptised en masse; the priests organised the converts into huge square formations by sex and sprinkled them with water while baptising everyone in each group with the same Christian name. The perpetual fire was extinguished, the altars were broken, the sacred forests were cut down, and the sacred snakes were killed (Plate 1).Footnote 3

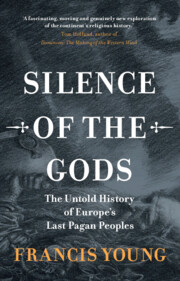

Plate 1 The Baptism of Lithuania by Władysław Ciesielski (oil on canvas, 1900), National Museum in Warsaw, Poland.

These events marked the official conversion of Europe’s last ‘pagan’ polity, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Christendom was, apparently, triumphant; and the conversion of Lithuania has often been taken as the high-water mark of the long process of conversion of the ‘barbarian’ peoples outside the Roman Empire that had begun a millennium earlier. It was the end of the imagined ‘pagandom’ that menaced Christian Europe. But the reality was rather different. As Jogaila stage-managed political and religious theatre in Vilnius, vast swathes of the continent of Europe remained unchristianised. The Prussians, Latvians, and Estonians, although under the thumb of crusading orders for centuries, had yet to embrace Christianity. Similarly, the Finnic Votians and Izhorians, in the sphere of influence of the Republic of Novgorod, had yet to become Orthodox, and a great swathe of animist peoples inhabited the far north of Fennoscandia and the Volga-Ural region in the far east of the Continent: the Sámi, the Karelians, the Nenets people, the Komis, the Maris, the Udmurts, the Mordvins, and the Chuvashes (to name just a few). At the level of geopolitics, the conversion of northern Europe to Christianity was indeed achieved at the end of the fourteenth century, and if history is only about the actions and decisions of ‘great men’, then that is all that matters. But in reality, many European peoples remained wholly or partly unchristianised for centuries thereafter. This book is about them.

There is a long history of fascination with ‘pagan survivals’ in modern historiography, beginning with a new Enlightenment attitude to religion in the eighteenth century as a culturally constructed phenomenon – a shift of attitude that will be explored in more detail in Chapter 5. Historians, ethnographers, and antiquarians became more willing to consider all religions on equal terms; and then the nineteenth century brought the advent of the disciplines of anthropology and folklore, which at the time were dominated by the idea that modern folklore and customs encoded impossibly ancient information about pre-Christian religions. Nationalism and secularism came together to render the imagined pagans of the past fascinating: idealised exemplars of nationhood who had existed before the cultural distortions imposed by colonisers and the imported faith of Christianity. The effect of all this was to make northern Europe’s long-vanished pagans into celebrities to rival the long-admired pagans of Greece and Rome: the druids of Gaul, Britain, and Ireland; the heathen Vikings of Scandinavia; the Germanic pagans of Wagnerian opera; and, for those who bought into the theories of Margaret Murray, the ‘pagan’ witches of early modern Europe.

In the midst of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries’ celebration of all things pagan, and the earnest search for ‘pagan survivals’ in everything from Morris dancing to nursery rhymes, the fact that pre-Christian religious practices endured into the early modern period in some parts of Europe was overlooked. This was, in large part, for historical and cultural reasons. Most of the peoples discussed in this book, with the notable exception of the Sámi of northern Fennoscandia, were then located within the borders of the transcontinental Russian Empire and were thus often excluded from discussions focussed on western Europe. Furthermore, nationalism inclined scholars to seek the evidence of ‘pagan survivals’ in their own nations and not to look further afield. And it was hard for scholars from far-flung corners of Europe to make their voices heard in a discourse dominated by German, British, French, or Italian scholars. Then, in the second half of the twentieth century, a new discourse of ‘paganism’ emerged, focussed on the revival (or reinvention) of pre-Christian religions in new religious movements – a discourse that sometimes pushed to one side the actual evidence for pre-Christian religions in favour of romanticised interpretations that matched the visions of revivalists.

The effect of all of this was to leave the story of the last phase of pre-Christian religion in early modern Europe largely untold, outside of those countries where it mattered as part of their national story. The purpose of Silence of the Gods is to provide a religious history of Europe’s last unchristianised peoples for the last five centuries of their existence. These peoples, and their religions, deserve more from historians than they have hitherto received; they deserve to be considered as more than an undifferentiated religious ‘other’ which Christianity displaced. For their history, if it has been told at all, has often been subsumed within a historiography of Christian mission and conversion, where the identities and beliefs of practitioners of pre-Christian religions were often left vague, or were unlocated in historical time – or imaginatively inferred from later folklore, rather than examined on the basis of contemporary documentary evidence.

No book could ever give a complete account of the pre-Christian religions of all European peoples who were still in existence in the early modern period, because there is simultaneously too much evidence and too little: too little historical evidence to give a clear picture of the true variety and structure of religious beliefs, and too much evidence to be teased from unreliable and mercurial sources like later folklore. But Europe’s unchristianised peoples were not wholly voiceless, with their beliefs and practices reported only by hostile Christian sources. It is true that these peoples are glimpsed mainly through a complex matrix of interpretation by Christians, but their voices do feature sporadically in missionary and disciplinary records from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.Footnote 4 Europe’s unchristianised peoples were neither passive recipients of ancient religious traditions from the distant past nor passive victims of Christianisation. They were as capable of agency and creativity in their belief systems as anyone else, and their beliefs underwent change and evolution during the early modern period. Unchristianised peoples rejected, ignored, or incorporated elements of Christianity into their religious outlooks on their own terms. That they were able to do so owed a great deal to the remoteness of their homelands and the rudimentary nature of ecclesiastical organisation and mission at Europe’s unchristianised edge, but it also speaks to a desire to innovate and respond to the changing world in which they lived.

The late date at which the final Christianisation of these peoples was attempted means that we are able to view their pre-Christian beliefs through the eyes of Renaissance humanists and Enlightenment philosophes who were reaching towards more modern methods of ethnography. The collision of modernity with pre-Christian religion offers the tantalising possibility that such detailed ethnographic testimonies bear witness to religious traditions and outlooks that were once much more widespread – a glimpse, as it were, of the otherwise lost pre-Christian religious heritage of all northern Europe. But early modern commentators also channelled their own concerns and anxieties into their writings, revealing as much about themselves and their own time as about the peoples they set out to describe. Not only was everything we know about pre-Christian peoples in this period written down by Christians, but Christianity and literacy almost always arrived together – so that the historian necessarily glimpses pre-Christian religion in the moment of its overthrow, as it were. The act of observation was entangled with the act of destruction.

The one historical fact that overshadows any history of Europe’s last unchristianised peoples is that, almost without exception, these peoples eventually were Christianised; that is to say, they internalised Christianity as part of their national identities. This book is thus about the end of a phenomenon (pre-Christian religion), which largely disappeared during the period it considers. As Pierre Chuvin observed of the last pagans of Rome, ‘it is much easier to point out the first time an event occurred than the last’.Footnote 5 But it is not the aim of this book to identify Europe’s ‘last pagan’; that would be a fruitless exercise, and it assumes an absoluteness to religious identities in this period that does not reflect the reality. Ambiguity about who exactly might be considered a Christian or not is an unavoidable feature of this history, rather than a problem to be eliminated – and it is partly to accommodate that ambiguity that I choose to write of ‘unchristianised peoples’ rather than ‘pagans’. Describing peoples as ‘unchristianised’ does not require us to imagine they were completely untouched by Christianity, or that they defined themselves against Christianity, as describing them as ‘pagan’ might. Large elements of Christianity might have been incorporated into their worldview, but the pre-Christian past was still a presence in the memory of the community. These peoples were, in other words, only shallowly Christianised; deep Christianisation (a concept I discussed in my earlier book Twilight of the GodlingsFootnote 6) involves a degree of cultural forgetting of pre-Christian traditions, so that folk religion involves the creative reinterpretation of a Christian cosmology rather than the incorporation of ‘pagan survivals’.

Early modern Europe’s unchristianised peoples were small in number, scattered in distribution, and generally politically powerless. Nevertheless, they mattered well beyond their own regions because learned and powerful elites were deeply concerned about their continuing existence. Rulers and churchmen fretted about the ‘last pagans’ within their dominions. The conversion of all peoples was central to Christian belief,Footnote 7 and the Christianisation of all peoples within a given territory according to the ruler’s religious preference was essential to post-Reformation understandings of sovereignty. Furthermore, the pre-Christian peoples of Europe, whether the Guanches of the Canary Islands or the Samogitians of the Baltic, became the ideological proving ground for European responses to Indigenous peoples in the New World that would ultimately challenge everything human beings thought they knew about themselves, with repercussions that continue to this day in urgent debates about the legacy of colonisation and Indigenous rights.

Furthermore, like the decline of the Roman Empire, which allowed for the emergence of the early medieval world, the decline of Europe’s pre-Christian religions seeded something new. The nineteenth-century’s reinterpretation of pre-Christian cultures, considered in Chapter 6, led to the rise of nationalism and movements for national rebirth in central and eastern Europe that produced many of the nations of the region, influencing geopolitics to this day. Furthermore, the position of national minorities within the Russian Federation – many of whom are considered in this book – is a matter of considerable contemporary interest as a volatile Russia’s medium- and long-term political future remains seemingly in the balance. As Christianity loses its religious and cultural hold on Europe, there is understandably an upswell of popular curiosity about what came before it, especially if pre-Christian peoples are perceived as having lived in harmony with a natural environment that is now in crisis. While Europe’s pre-Christian religions ultimately faded from history, their memory became part of the material for newly fashioned identities, and that material remains a significant (if at times problematic) part of Europe’s cultural fabric. It is impossible to understand the totality of early modern European history without including unchristianised peoples in the story.

Speaking of Pagans

There is a long-standing debate among scholars of religious studies, as well as historians, about the use of the word ‘pagan’ to describe pre-Christian European cults.Footnote 8 Scholars who reject the use of the word ‘pagan’ generally do so because it is an ‘othering’ term invented by Christians in order to define Christianity against what it was not. On this view, ‘pagan’ is a pejorative term; but it is also a meaningless one, since anyone who was not a Christian (or who failed to meet a required standard of ‘Christian-ness’) could be called a pagan. It was not a word that anyone ever used of themselves. I have argued elsewhere that rejection of the word ‘pagan’ on these grounds is problematic,Footnote 9 not least because there are now people who call themselves pagans and identify with the pre-Christian religions of the past. Furthermore, ‘pagan’ is among those terms in the history of belief, like ‘religion’, ‘magic’, and ‘witchcraft’, that stubbornly resist unproblematic definition, but that non-specialists continue to use anyway. While the use of such terms should always be subject to critique and appropriate qualification, I take the view that abandoning a widely recognised and widely used term altogether requires exceptional justifications – not least because historians have little hope of communicating their ideas to the wider public if they decline to use commonly understood terminology.

While it is true that ‘pagan’ was (until very recent times) an exonym or etic term for a group of people defined by an external authority (the Christian church), the extent to which that definition was arbitrary should not be exaggerated. As we shall see, ‘pagan’ was a term used both technically and rhetorically by late medieval and early modern Christians. While it may not always be apparent that, in the heat of argument and polemic, the ‘rhetorical pagan’ and the ‘technical pagan’ were always clearly distinguished, theologians certainly retained the capacity to distinguish them. In the rhetorical sense, heretics, apostates, exceptionally ignorant Christians, and people forbidden from receiving the rites of the church under interdict or excommunication – and, later, people accused of witchcraft – might be called ‘pagans’. But in the technical sense that these people were baptised and therefore stood under the authority of the church’s canon law, they were not pagans. In the eyes of the church, baptism claimed a person for Christianity, regardless of that person’s level of understanding or catechesis, and a pagan in the technical sense was any unbaptised person who was not a Jew.

Where medieval theologians disagreed about the status of a group of people as pagans or not was in discussions of Islam, where interpretations were divided between those who considered Islam a kind of Christian heresy and those who believed Muslims were pagan idolaters.Footnote 10 Derived from the ninth-century author Nicetas of Byzantium,Footnote 11 and incorporating the libel that Muslims worshipped a trinity of false gods as idols (including ‘Mahumet’), the belief that Muslims were pagans provided a convenient justification for the Crusades, since pagans could be blamed for the death of Christ.Footnote 12 Furthermore, the ‘paganisation’ of Muslims headed off troubling questions about how another successful proselytising monotheistic religion with equally exclusive claims to divine favour could exist. However, since the Qur’an plainly referenced the Old Testament and mentioned Jesus, Islam could also be written off as a peculiar kind of Christian heresy.

While Christian attitudes to Islam lie beyond the scope of this book, the purported reasons why many medieval Christian commentators considered Muslims to be pagans bear examination. In addition to being unbaptised, Muslims were also pagans on account of their alleged idolatry and polytheism. Again and again, Christian authors associated paganism with the worship of idols and the veneration of multiple deities – with good reason, for the ultimate authority for the Christian definition of paganism was the Bible (even if the Latin Vulgate never once uses the word paganus). In the Old Testament, the Israelites and their leaders are repeatedly deemed to have fallen away from God when they turn to the worship of ‘strange gods’, ‘the gods of the nations’, or ‘the idols of the nations’.Footnote 13 Since the prophets of ancient Israel were reacting against a particular kind of non-Yahwistic religion, that Canaanite religion became the blueprint for the kind of paganism Christians expected to encounter – along with the paganism of the ancient Graeco-Roman world whose collision with Christianity is described in the Acts of the Apostles.Footnote 14 Christians thus expected to find pagans worshipping at temples, sacrificing animals (and perhaps even people), and venerating valuable cult images as actual deities. The Christian reinvention of Islam as idolatrous paganism was a particularly extreme form of a broader pattern of Christians interpreting every non-Christian religion they encountered via a scriptural hermeneutic.

The principal reason I have chosen not to use the term ‘pagan’ in this book without careful qualification (preferring ‘pre-Christian’ or ‘unchristianised’) is that ‘pagan’ fails to do justice to the variety of beliefs and rites present in European societies before Christianisation – even if I do not think it is not a term that should be avoided altogether. The word ‘pagan’ evokes certain associations. Traditionally, those are associations with Greece and Rome, with its polytheistic pantheon of deities, temples, animal sacrifice, and anthropomorphic cult images. Put another way, ‘pagan’ is a word that triggers a latent hermeneutic of interpretatio Romana, where every pre-Christian society is judged against the implicit standard of the pagan society we know most about: Graeco-Roman antiquity. In more recent times ‘pagan’ is a word that has arguably acquired other connotations too: positive ones, such as an association with the uninhibited celebration of life, sexual liberation, and closeness to nature.Footnote 15 This too is a problem: it is every bit as unhistorical to project the attitudes and ideals of contemporary paganism back onto the pre-Christian peoples of the past as it is to expect all those peoples to behave like Greeks and Romans.

The peoples whose religious history is the subject of this book deserve to be unburdened from some of the unspoken assumptions that a word like ‘pagan’ carries with it. Their spiritual beliefs and practices were often very far from any template offered by Greece or Rome. In most cases, by the time we have any evidence for the pre-Christian religions of northern and eastern Europe those religions were perceived as marginalised and in decline. The temptation, therefore, has been to lump them all together. These people were ‘pagans’, ‘animists’, ‘shamanists’. To the Russians they were all ‘Chuds’, a generic mass of Finno-Ugric-speaking animists. But the religious diversity of Europe’s pre-Christian religions, like the diversity of its languages, was vast; and even if it is often now impossible to recover the true extent of that diversity, it deserves to be acknowledged. The limitations of our sources mean we can only glimpse the richness of the tapestry of Europe’s later pre-Christian religions, but enough evidence survives to show that it is very difficult to generalise about the beliefs of different peoples. The use of a generalising term like ‘pagan’ suggests a lack of imagination, funnelling us towards an interpretation of pre-Christian religions as nothing more than lingering survivals from an earlier era and implicitly excluding the possibility that these religions were capable of change and development too.

Potential alternatives to ‘pagan’ and ‘paganism’ include ‘pre-Christian religion’, ‘Indigenous religion’, ‘native faith’, and ‘ethnic religion’. In a study of the terms used to describe Sámi religion, Konsta Kaikkonen has been critical of the term ‘pre-Christian’ on the grounds that it clearly locates a religion in the past. In Kaikkonen’s view, the use of ‘shamanism’ is similarly problematic, since it is socially constructed and ‘irons out differences between all “shamanistic” cultures and simply sees them as sides of the same phenomenon’.Footnote 16 Vladimir Shumkin questioned the uncritical application of a model derived from Siberia to the Sámi noaidi (in Sámi culture, a person who communicates with the spirit world), arguing for greater cultural distinctiveness.Footnote 17 Ronald Hutton added a further qualification to the term ‘shamanism’, noting that shamanism is only one aspect of the religious outlooks in which shamans operate, and therefore it might not be appropriate to characterise an entire religion by that one practice.Footnote 18

As an alternative to earlier terms, Kaikkonen suggests the use of ‘Sámi autochthonous religion’; or, alternatively, ‘a more particularistic type of approach’ that uses purely Sámi terms like Noaidevuohta.Footnote 19 Clearly, the adoption of such ‘particularistic’ terms gives a more distinctive identity to a people’s religion and avoids the danger of lumping all non-Christian religions together as one undifferentiated mass of ‘pagan’, ‘animist’, or ‘pre-Christian’ beliefs. However, if we are concerned with redressing the marginalisation of Europe’s pre-Christian religions, ‘particularism’ is not necessarily the right way to go. It makes it harder to talk about these religions, and it risks the ‘Balkanisation’ of pre-Christian religions through the use of particularising language that makes it impossible to speak of common themes or connections – thereby hampering the spread of knowledge and understanding of pre-Christian religious traditions beyond one region. I have already highlighted the difficulty of generalising about pre-Christian religions, but there is also solidarity to be found in appropriately qualified generalisations, provided facile comparisons are avoided. And there is, of course, one experience that unites all the diverse pre-Christian religions of medieval and early modern Europe: the experience of contact with Christianity and attempted Christianisation.

Terms like ‘Indigenous’ and ‘autochthonous’ are problematic because the application of the concept of indigeneity (developed primarily in the Americas) to Europe remains controversial.Footnote 20 While there is no authoritative definition of what constitutes an Indigenous people, influential definitions often highlight the colonisation of the territories of Indigenous peoples by settler societies rather than simply the ‘autochthony’ of Indigenous peoples as the earliest known inhabitants of a region.Footnote 21 There is a debate in Estonia, for example, about whether the Estonians – repeatedly colonised by Baltic German, Danish, Swedish, and Russian settlers, and most recently by the Soviet Union – should consider themselves (and be considered) an Indigenous people, and a rhetoric of ‘indigeneity’ is part of the self-understanding of the ‘native faith’ Maausulised movement.Footnote 22 But in the extension of the concept of indigeneity to Europe there is a latent danger of the appropriation of the term by far-right ultra-nationalist groups, potentially allowing any group that claims ‘autochthony’ to define itself as ‘Indigenous’ and re-articulate xenophobic nationalisms in terms of ‘Indigenous rights’.

‘Pre-Christian religions’ is, in my view, the least problematic and most readily understandable term which can be meaningfully deployed to identify the historic belief systems of the Sámi, the Finno-Ugric-speaking animists of European Russia, the Estonians, the Balts, and others. It is a term that leaves open the possibility of vast differences within and between those belief systems, in contrast to ‘paganism’ (with its Graeco-Roman associations) or ‘animism’ (which may not accurately characterise the belief systems of all these peoples). It allows for the exploration of both the general and the particular. In a discussion of teaching about Sámi religion in Norwegian schools, Bengt-Ove Andreassen and Torjer Olsen are hesitant about the term ‘pre-Christian’, noting that it pushes Sámi religion into the past and places Christianity in a central position.Footnote 23 But this is not the only way to interpret the term. It is undeniable that Sámi religion, along with every other form of pre-Christian religion in Europe, has come into contact with and been affected by Christianity (or Islam). To refer to a religion as ‘pre-Christian’ is to acknowledge that a relationship with Christianity is part of the history of these religions, yet it does not presume priority for Christianity. Indeed, the term ‘pre-Christian’, as used in this book, grants ontological priority to religious traditions that preceded Christianity; it refers not just to a pristine state of religion before any contact with Christianity, but to any religious practices in a society before its thorough Christianisation. It is shorthand, in other words, for ‘pre-Christianisation’ religions.

Blurred Boundaries: Religion, Animism, Creolisation, and the ‘Christianesque’

While it may be possible to recognise some commonalities with Graeco-Roman religion in the religious concerns of the animists of Europe’s far north and east, the differences are more pronounced than the similarities. Animism (and indeed shamanism) cannot and should not be lumped in with ‘paganism’.Footnote 24 For the purpose of a recent study of the Komi people of European Russia, the Estonian scholars Art Leete and Piret Koosa defined animism as ‘an animal- and spirit-related mode of vernacular sensitivity, a complex way of perception, thought, and action that encompasses human and other-than-human persons’.Footnote 25 Clearly, nothing about this definition necessarily requires polytheism, sacrifice, temples, cult images, and so forth. Indeed, it is not altogether clear from this definition that animism need be considered ‘religion’ at all. As Graham Harvey has observed, scholars now generally reject definitions of animism in terms of belief (‘belief in spirits’, for example), preferring to see it in terms of ‘a concern with knowing how to behave appropriately towards persons, only some of whom are human’.Footnote 26 Madis Arukask, in a study of Finno-Ugric-speaking herdsmen in Russia, puts the emphasis on partnership between human beings and the forest and supernatural forces, leading to a ‘contractual’ relationship.Footnote 27 The animist outlook is thus the opposite of the modern Western interpretation of humanity’s relationship with nature as adversarial, expressed through metaphors of conflict and conquest.

‘Religion’ is a term that is notoriously difficult to define. But animism (as usually conceptualised) differs significantly from both Christian and Graeco-Roman modes of religiosity, not least because its concerns are seemingly different from those of religion. It is perhaps because animism ‘flies under the radar’ of religion that animism manages to co-exist in some societies and individuals with the public profession of Christianity or Islam. Emma Wilby and Michael Ostling have argued for the idea that animism is in some sense more fundamental than religion, a kind of ‘bedrock’ of popular belief that can continue to exist beneath layers of religion, resilient to religious changes.Footnote 28 To use an analogy from linguistics, animism could be seen as a cultural ‘substrate’ to most societies, perhaps long since extinct in and of itself, but nevertheless detectable in later religious and ritual vocabularies. In 2014 a Mari woman, Nastia Aiguzina, told a BBC journalist that ‘In the morning people might attend church and in the afternoon visit the sacred forests.’Footnote 29 I had a similar conversation in 2023 with a professor of Sámi language at the University of Tromsø in Norway, who noted that many Sámi people who identify as Lutheran Christians may ask permission of the spirits before lighting a fire or camping in a specific place in the landscape. At one time such phenomena were conceptualised as ‘dual-faith observance’,Footnote 30 but this missed the point that religion and animism do not co-exist as equivalents. Animist traditions may not interact with religious beliefs at all, and the perception that animism is ‘pagan’ or in potential conflict with the profession of Christianity is externally projected by academics, journalists, or missionaries onto societies in which animism still remains significant; it may not be a tension felt by animists themselves.

On the other hand, by defining animism as something other than religion we may risk perpetuating, in a different form, the sort of closed thinking about religion that caused missionaries to despise the practices of animist peoples. While animism need not compete with Christianity within a Christianised society, and its presence need not be seen as indicative of some sort of conscious compromise or syncretism, excluding it from the category of religion altogether risks denigrating or demoting it. The continued presence or absence of animism in a society can perhaps be taken as a measure of the depth or cultural thoroughgoingness of that society’s Christianisation – in the sense that Christianity typically becomes a more and more ‘culturally totalising’ presence in a society over time. This is not because the adoption of Christianity necessarily requires the thorough Christianisation of every aspect of life, but because the abandonment of traditional religions can result, over time, in a collective forgetting of the pre-Christian context for those cultural practices, and thus they are furnished with new Christian contexts and rationalisations. A good example would be Ilgės or Vėlinės, the ‘Lithuanian Day of the Dead’, which in all likelihood has pre-Christian origins, but has now merged into the mainstream of traditional commemorations of the departed that are common in many Christian countries in late October and early November, clustering around the feast of All Saints.

The continued presence of elements of animistic belief and practice in a society could be taken as a sign that its Christianisation is fairly recent, or that it was not wholly successful for a long time. Timothy Insoll has argued that the identification of a society with Christianity (or, looked at another way, a society’s self-identification as a Christian society) can take a long time, and it is the final stage of Christianisation.Footnote 31 As Hutton has argued, Christianity was not always immediately successful in supplying substitute beliefs for every aspect of pre-Christian religion. Christianity is a religion primarily concerned with the soul’s eternal destiny rather than with the pragmatic realities of life in a rural subsistence society, or indeed a nomadic society based on hunting and foraging. As Hutton puts it, ‘the sheer otherworldliness of Christianity … forced medieval people to retain memories of ancient pagan beliefs in order to cope with the present world’.Footnote 32 The persistence of animism and the retention of other pre-Christian beliefs and practices may not, therefore, be indicative of any kind of conscious departure or dissent from Christianity. Rather, it reflects the necessity of navigating the personhood of non-human beings as part of one’s perception of reality.

Just as ‘animism’ can prove a problematic concept, so the concepts of ‘crypto-religion’ and ‘syncretism’ are not altogether satisfactory for dealing with the presence of older beliefs and practices in a society alongside Christianity. The phrase ‘crypto-religion’ seems to imply that older beliefs must be concealed beneath a veneer of Christian devotional practices – which is by no means always the caseFootnote 33 – while the concept of ‘syncretism’ implies that older beliefs survive primarily by being assumed into or synthesised with the dominant religion (or at least its popular expressions). John Marenbon has argued that it is perfectly possible for people to inhabit more than one tradition or conceptual scheme without synthesising them,Footnote 34 and our need to see a synthesis of belief in other societies may say more about us than it does about them. In other words, because a post-Enlightenment mindset renders us incapable of inhabiting more than one world of belief without consciously synthesising or harmonising them, we imagine that it is so for everyone else. But there is no good reason to suppose that unchristianised peoples were insincere (or set out to deceive) in their incorporation of elements of Christianity into their religious practices, and no evidence that they deliberately and cynically relabelled gods and goddesses in order to evade the attention of church authorities.

On the other hand, there is evidence that unchristianised peoples often populated a partially pre-Christian framework of belief with Christian characters during the Christianisation process, as one possible intermediate stage between pre-Christian cult and thorough Christianisation. These, in the words of Tuuli Kurisoo and Tõnno Jonuks, are the people ‘who use Christian symbolism while living in a pagan society’, like medieval Estonians who happily wore jewellery featuring crosses long before it is likely that any conversion had taken place,Footnote 35 or the early Anglo-Saxon leader buried in Sutton Hoo’s Mound 1 in the seventh century with a mixture of pagan and Christian artefacts. At an early stage of their contact with Christianity, people might retain a pre-Christian outlook based on polytheism, sacrifice, and the placation of deities, yet choose to sacrifice to the Christian god and the saints as well on the grounds that the Christian God was a powerful deity worthy of worship – in the absence of any understanding of Christianity’s radical claims of exclusivity for its deity.

I have argued elsewhere that worship of Jesus as one god among many may explain some of the more baffling archaeological evidence for religion in late Roman Britain,Footnote 36 and the popularity of Christian imagery on early modern Sámi drums has been interpreted in much the same way: the addition of a Christian cast of characters to an existing set of beliefs.Footnote 37 To argue endlessly about whether those who have adopted the supernatural personnel of Christianity (God the Father, Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints) but show no apparent commitment to monotheism are ‘Christians’ or ‘pagans’ is to miss the point and deal in essentialist conceptions of religious allegiance that fail to do justice to the fluidity and creativity of an era of religious transition. If a puppeteer adds puppets of Marvel superheroes to a traditional Punch and Judy Show that does not make the puppet show part of the Marvel franchise. In medieval and early modern Europe ‘there could have been “Christians” who had nothing to do with the “real” Christianity’Footnote 38 – people who identified with Christian imagery and Christian religious figures before they understood anything of what it meant. As Kurisoo and Jonuks note, we do not really have a word for this sort of relationship with Christianity,Footnote 39 although I propose we could refer to it as the ‘Christianesque’: a cosmetic adoption of features of Christianity without adoption of the Christian faith in a way recognisable to the church authorities. And just as there were ‘Christianesque’ unchristianised people incorporating Christian themes into pre-Christian belief worldviews and belief systems, there were also ‘paganesque’ Christians who continued to use pre-Christian rites but whose overall belief system was Christian, to the point where, in Slavic lands, even Christian priests participated in ‘paganesque’ rites.Footnote 40

The phenomenon of the ‘Christianesque’ is closely linked to another idea central to the argument of this book: the concept of religious creolisation. The idea of creoles arose first in linguistics to describe new languages formed in a colonial context from the interaction of Indigenous and colonial languages, and the corresponding concept of religious creolisation was initially developed to understand the complex religious traditions of people of African descent in the Caribbean and Latin America; for North America, the term métisisation might also be used, in reference to the new Métis culture created by a fusion of French settler and Native American traditions. However, the creole paradigm is increasingly applied by archaeologists and ancient historians to the religions of ancient Europe. In the same way that a linguistic creole is a stable new language developed from the combination of elements of two interacting languages, so that it can no longer be accurately described as a variant form of either one of those two languages, the creole religions of black communities in Caribbean and Latin America cannot be described satisfactorily as manifestations of either Christianity or African traditional religions. A third religion has come into being as a result of contact and interaction between multiple traditions.Footnote 41

The concept of creole religion as a sort of religious bricolage undermines the traditional Christian–pagan binary in the historiography of European religion. Whereas the ideas of ‘crypto-religion’ and syncretism presuppose the interaction of two distinct religious traditions in a dynamic of dissembling and conscious compromise, the paradigm of creolisation allows for something more organic and more fluid: the emergence of a new system of ritual and belief from cross-cultural interactions. The Christianisation of Europe can thus be reimagined as an interplay between three religious traditions – Christianity itself, the largely unrecoverable religions of peoples untouched by Christianity, and various creole traditions developed in response to contact with Christianity but prior to complete Christianisation. The re-conceptualisation of pre-Christian religious traditions as creole religions enables the historian to break free of the assumption that the religious beliefs and practices of unchristianised peoples in Europe always had their roots in the distant past. For example, some scholars have suggested that the Samogitian god of merchants Markopollus, first mentioned in the sixteenth century, could have been a corruption of the name of the explorer Marco Polo,Footnote 42 and nineteenth-century folklorists noted that Latvians had added a new goddess, ‘Mother of Tobacco’, to the many Latvian divine mothers.Footnote 43

The archaeologists Ralph Haeussler, Elizabeth Webster, and Jane Webster have been among the first to apply the paradigm of creolisation to the religions of Europe, albeit in ancient rather than modern times.Footnote 44 For these scholars, creolisation provides a better framework than ‘Romanisation’ to describe the transformation of local cults in the provinces of the Roman Empire, since ‘Romanisation’ implies the imposition of one culture from the centre of the empire onto its peripheries. The archaeological evidence suggests the real situation was more complex, with peoples colonised by the Roman Empire exercising their own agency to create new, composite religious traditions in response to Roman religion. Elsewhere I have discussed the extent to which some of the cults of Roman Britain – such as the cults of Brigantia or Faunus – might have been neither truly ‘Roman’ nor truly ‘Celtic’, but new cults created in Britain as the need for them arose.Footnote 45 The binary interpretation usually applied in the study of Romano-British religion – that every cult was either an import from the Roman world or a survival from Iron Age British religious practice – is inadequate, because it ignores the possibility that people in Roman Britain were capable of religious creativity.

The same critique of the shortcomings of ‘Romanisation’ can also be applied to the idea of ‘Christianisation’ at a later period. Christianisation is a problematic concept because it implies a one-way transfer of religious influence, emanating from the centres of Christian authority and power, which gradually turned ‘pagans’ into good Christians. However, Christianisation took many forms, from the haphazard adoption of ‘Christianesque’ beliefs and practices by unchristianised peoples to the forcible imposition of Christianity by political power – and everything in between, including sincere, heartfelt conversion resulting from non-violent missionary activity. What is clear, however, is that contact with Christianity did not extinguish pre-Christian beliefs. Instead, it often re-formed them into new creole belief systems and cults that reflected neither a pristine pre-Christian cult nor proper assimilation into the Christian world. Furthermore, like the creole religions of the Caribbean, the creole religions of Europe were a response to crisis. That crisis, for European peoples, was not total separation from their ancestral homelands and traditions; rather, it was the destruction of their religious traditions by missionaries who did not then provide the pastoral and educational infrastructure for Christianity to become culturally embedded. People were left in a religious no-man’s land, simultaneously de-paganised and unchristianised, and responded by creating creole religions as best they could.

The notion that creole religions existed in early modern Europe represents a challenge to the two broad historiographical paradigms that have been applied to Christianisation: a ‘paganising’ paradigm derived from nineteenth-century nationalism, which prefers to see pre-Christian religion as largely pristine and presents Christianity as a culturally destructive force; and a ‘Christianising’ paradigm in which Christianity was wholly triumphant and forged new identities for Christianised peoples within Christendom. These historiographical tendencies might be considered the ‘maximalising’ view of pre-Christian religion – that it survived to a late date – and the ‘minimalising’ view that pre-Christian religion was extinguished early and later reports of ‘paganism’ were simply invented, imagined, or misinterpreted by commentators (a view taken, for example, by the German historian Michael BrauerFootnote 46). Hutton has astutely observed that the excessive reification of ‘paganism’ in societies that had already experienced a conversion event results in ‘endless, and irreconcilable, arguments over the extent of the survival of the essence of a religion when the people who professed it have been formally converted to another’.Footnote 47 Put another way, the historian searching for ‘pagans’ in late medieval and early modern Europe risks becoming entangled in a fruitless ‘no true Scotsman’ line of reasoning, endlessly defending the idea that this or that group of people ‘were pagans at heart’, in spite of evidence for their extensive contact with Christianity.

But there is another reason to avoid essentialism in the discussion of ‘paganism’ and Christianity in the societies of northern and eastern Europe – the epistemological ‘elephant in the room’. This epistemological elephant is the difficulty of saying anything about how Christianity and pre-Christian religion interacted when we know virtually nothing, in many cases, about pre-Christian religion before it came into contact with Christianity. What passes for a description of ‘pagan’ religion is often, in all likelihood, a description of creolised practice. A pivot to understanding the religions of unchristianised peoples as creole belief systems removes the need to engage in arid essentialist debates about who was or was not a pagan or what exactly constituted ‘true’ paganism. It reveals the slow progress of Christianisation in some regions of eastern and northern Europe as neither the plucky survival of paganism against all the odds, nor the overwhelming success of Christianity, but rather the creative response of people who chose their own ways to worship the divine in response to a spiritual and pastoral crisis.

Conversion, Christianisation, and Unchristianised Peoples

In the 1970s the Norwegian missiologist and Lutheran bishop Fridtjov Birkeli distinguished between a ‘conversion event’ and the process of Christianisation that follows it,Footnote 48 introducing a more refined understanding of Christianisation than earlier models which conflated conversion and Christianisation. Simply put, a ‘conversion event’ is a society’s outward adoption of Christianity, either through mass self-identification with Christianity or through a ruler’s decision to adopt the Christian faith. Conversion events are themselves historically complex, usually coming at the end of a long road that begins with a culture’s first contact with Christianity, and they are not always clearly defined – especially if a culture is highly decentralised. This is why it is very difficult to determine a date for such a conversion event for the Sámi, a collection of peoples with no overarching political organisation spread over a vast area of northern Fennoscandia from the Atlantic coast of Norway to the Kola Peninsula. Determining the date of a conversion event by a leader’s decision to adopt Christianity entails large assumptions about the political structure of a region and it is not altogether clear how colonised nations with no political autonomy fit into such a definition. The ‘conversion’ of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which marks the terminus post quem of this book, is one such event. On the one hand, it can be precisely dated to February 1387; but on the other, it is unlikely to have involved more than a few hundred people in the city of Vilnius.

Whether or not ‘conversion events’ can be defined satisfactorily, it is nevertheless clear that no society becomes thoroughly Christian in a single event. Christianisation is the long process of cultural assimilation of Christianity into all aspects of life that follows the conversion event, including catechisation of the population so that they understand Christianity as well as simply deciding to identify with it. Some Christianisations were fairly rapid. Ireland could serve as an example of a country where Christianisation was successful, from ‘first contact’ with Christianity in the early fifth century (at the latest) to an end to pre-Christian cult by high-status individuals in the mid-sixth century. By 600 ce Ireland had been ‘converted on the level of hierarchy and institution’, and by 700 ce even ‘increasingly marginalized manifestations of non-Christian religion’ were gone.Footnote 49 In Anglo-Saxon England, likewise, conversion at the elite level was complete by around 680, having begun in 597. Neither early medieval Ireland nor Anglo-Saxon England were anything like a modern unitary state, but regardless of political fragmentation there were strong ties of kinship between different political units as well as an implicit or explicit hierarchy of rulers and sub-rulers which ensured that Christianity snowballed once the most influential rulers endorsed it. A further factor behind the rapid Christianisation of England may have been the prestige of the religion of late imperial Rome, which cast its seductive glamour over early medieval England – a heady cocktail of Christianity, Roman cultural prestige, and the promise of mimicking imperial power.Footnote 50

Christianisation in some other nations was notably slower and beset with reverses – such as Hungary, Scandinavia, and the lands of the West Slavs. But, in the Baltic region, Christianisation ground to a halt altogether. The specific reasons for this will be examined in more detail in Chapter 1, but Sylvain Gouguenheim has singled out four factors that account for the failure of Christianisation in the Baltic: negligent missionaries, poor church infrastructure, geographical distance and remoteness, and the language barrier.Footnote 51 While these four factors were undoubtedly significant, Gouguenheim’s analysis omits a fifth factor: active resistance and rejection of Christianity by the local population. For peoples undergoing Christianisation were not merely passive recipients of a faith, with their acceptance or rejection of the faith dependent on the skill and diligence of missionaries. Pre-Christian peoples had agency. In his study of Samogitia (site of Europe’s last conversion event), Mangirdas Bumblauskas breaks conversion and Christianisation down into four stages: mission Christianisation (activities preceding a conversion event), official conversion, broad conversion (some level of outward identification with Christianity), and inner Christianisation. The latter did not occur in Samogitia, in Bumblauskas’s view, until the late eighteenth century.Footnote 52

The fact that Christianisation could not only fail, but might also be actively rejected, seldom receives the attention it deserves in histories of the conversion and Christianisation of Europe. Furthermore, we should also consider the possibility that the fairly swift outward adoption of Christianity could be the best way for a people to preserve their religious traditions and redirect the attention of missionaries. Often, the very idea of writing a history of conversion and Christianisation implicitly privileges Christianity over whatever it replaces, by placing the emphasis on the growth of Christianity rather than on the response of followers of pre-Christian religions, which may be seen as a heterogeneous mishmash of traditional religions and beliefs with insufficient unity or cultural power to resist the new faith. This was a particular problem in the traditional historiography of the Baltic Crusades, for example, where the religion of the crusaders’ enemies received little attention (in spite of its self-evident resilience, which was the reason for the crusades in the first place). This is in part due to the nature of the sources, all of which were written by Christians. But it also reflects, consciously or unconsciously, a teleological historiography of Christianity as the ‘inevitable’ religion of northern Europe – or, in somewhat more secular terms, a teleological historiography of the inevitable adoption of Christianity as a higher stage of religious development, to be succeeded in due course by secularisation.

In the period considered by this book, there existed both baptised and unbaptised unchristianised peoples in Europe. What unchristianised peoples had in common was that they did not integrate Christianity in any significant way into their culture, continuing pre-Christian practices not only concerned with life events such as birth, marriage, death, and burial but also practices of a decidedly ‘religious’ character, such as sacrifices and the veneration of images of deities. As David Petts has argued, there is no prima facie reason to view the continuance of pre-Christian rites of betrothal, marriage, burial, or commemoration of the dead in post-conversion societies as continuations of pre-Christian religion, as the church often did not take an interest in imposing its own norms and rituals on these customs until many years after a conversion event.Footnote 53 What, then, was the content of pre-Christian religion that marked a people as unchristianised? Bumblauskas singles out three key factors that mark the end of a pagan society: the end of sacrifices to gods, the baptism of all adults, and the establishment of a meaningful parish system.Footnote 54 Building on these observations, I suggest five factors that, either singly or together, might lead us to suspect we are dealing with unchristianised people rather than just ignorant or deviant Christians:

1. Active rejection of the church or the Christian faith.

2. The presence of significant numbers of unbaptised adults in the community.

3. Sacrifices and libations to specific, named pre-Christian deities.

4. Worship of images of specific, named pre-Christian deities.

5. Veneration of natural features such as trees, rocks, and bodies of water in a manner unconnected with Christian piety.

Even here, however, we must tread carefully. While open rejection of the Christian faith is the clearest way in which unchristianised people could show agency, such rejections are not often recorded and they may sometimes have been exaggerated – such as when disobedience to authority and rejection of a new pastor or new devotional practices were presented as the outright rejection of Christianity, for example. Sacrifices and libations, as we have seen, might be offered to Christian saints as well as to pre-Christian deities – and it is not always clear whether we should interpret such acts as ‘pagan’. Furthermore, the offering of libations can shade into folk custom – few scholars would seriously suggest, for example, that people leaving milk and cream out for the fairies in rural Ireland constitutes an act of pagan sacrifice. And it can be hard to establish with certainty whether an alleged pre-Christian deity really was a pre-Christian deity. Acts of piety undertaken at natural landscape features might be interpreted as ‘pagan’ just because they deviated from official Christian practice and not because they actually perpetuated pre-Christian cults. Nevertheless, it remains the case that the presence of one or more of these features should lead us to suspect the presence of pre-Christian religious traditions unincorporated into an essentially Christian worldview.

Histories of ‘Pagan’ Europe

A great deal has been written about Europe’s last pre-Christian religions, but most of it has not been written by historians of religion, has generally been highly focussed on one specific nation or region, and has often not been written in English. For today’s Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, Sámi, Maris, and others, the unchristianised peoples of the early modern era are ancestors – and not only ancestors, but often mythologised heroes and bearers of national identity. However, the story of Europe’s last pre-Christian peoples – and, indeed, their very existence – is one that is often poorly known outside Fennoscandia and eastern Europe. To date, only one book in English has attempted to deal generally with the theme of the persistence of pre-Christian religion in Europe into the early modern era.Footnote 55

The historical theme of the ‘last pagans’ has attracted a degree of scholarly attention, but this is focussed primarily on one context: the last pagans of Rome.Footnote 56 There is also a considerable (and ever-growing) literature on the revival of paganism in modern times,Footnote 57 but its historiography seldom reaches any earlier than the nineteenth century. My own volume Paganism Persisting, co-authored with Robin Douglas, is an attempt to push the history of revivals of paganism much further back – indeed, into antiquity itself.Footnote 58 Furthermore, there is some literature on the pagan theme in learned discourse in the Middle Ages.Footnote 59 Not every account of the ‘last pagans’ has confined itself to Europe, with some scholars taking in the Near East on the grounds that late Graeco-Roman paganism was highly influential there,Footnote 60 while the pre-Christian religions of the Sámi and other Finno-Ugric-speaking peoples of the far north have sometimes been considered in a ‘Circum-Polar’ rather than European context – on the basis that the commonalities with Siberian and Inuit religion are more salient.Footnote 61

Much of the scholarship on Europe’s pre-Christian religions is to be found in the fields of church history and archaeology, and specifically studies of the conversion of Europe and the Northern Crusades.Footnote 62 While much of this research is excellent, the primary purpose of such studies is to trace the development of Christian mission and Christianity’s eventual dominance, and they are not focussed on the pre-Christian peoples themselves and their religion. While not specifically about religion, S. C. Rowell’s Lithuania Ascending (1994) broke ranks by concentrating on the pagan Lithuanians themselves, albeit in a time period earlier than that covered by this book.Footnote 63 Sylvain Gouguenheim’s recent French-language book Les derniers païens (2022) is noteworthy for being devoted to Baltic pre-Christian religion and taking the history of that religion right up to the eighteenth century.Footnote 64 While not focussed exclusively on religion, the work of Rein Taagepera and Neil Kent provides a crucial survey of the Sámi and other Finno-Ugric-speaking ‘animists’ at the fringes of Europe,Footnote 65 while Andreas Klein has recently produced an indispensable guide to seventeenth-century antiquarian interest in the Sámi.Footnote 66

There are now a number of editions of medieval and early modern sources on late manifestations of pre-Christian religion in Europe, including Juan Antonio Álvarez-Pedrosa’s edition of sources for Slavic religion and my own edition of early modern primary sources on Baltic religion.Footnote 67 The scholarship of Norbertas Vėlius and, more recently, Vytautas Ališauskas, has made available a comprehensive collection of extracts from primary sources in the original languages (and Lithuanian translation) dealing specifically with alleged survivals of pre-Christian religion to the end of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.Footnote 68 The work of the Czech Balticists Marta Eva Bět’áková and Václav Blažek in producing the Lexicon of Baltic Mythology (2021) is also a very welcome contribution to this field.Footnote 69 However, even when written in English, the research of scholars from Fennoscandia and eastern Europe often does not receive the attention it deserves, largely because the history of pre-Christian religions is deemed a matter of local interest and its importance for the wider religious history of Europe goes unrecognised.

As we have seen, one of the key debates about pre-Christian religion in early modern Europe is whether it existed at all. At the ‘maximalist’ end of the spectrum on this question, largely superseded in scholarship but still strong in the popular imagination in many countries (including Britain and Ireland) is the idea that all folk culture is essentially ‘pagan’. The view that medieval Europe was only superficially or cosmetically Christianised is associated above all with Jean Delumeau, who argued in the 1970s that the Protestant Reformers and the Catholic missionaries of the Counter-Reformation effectively had to convert Catholic Europe to Christianity properly for the first time.Footnote 70 In the Baltic region, folklorists such as Pranė Dundulienė and Jonas Trinkūnas (the latter a key figure in the pagan revivalist Romuva movement) could be associated with this trend.Footnote 71 Clearly, to those interested in reviving pagan religions as a living reality (and indeed those interested in boosting a region’s tourist industry), the idea that folk culture has somehow ‘encoded’ pre-Christian religious beliefs and practices is especially seductive, because it makes it possible to fill the (significant) gaps in our direct knowledge of pre-Christian religion by reverse engineering or ‘re-paganising’ a folk culture presumed to be pagan in the first place.

At the ‘minimalist’ end of the spectrum lie the extreme sceptics, who have questioned whether there is any compelling evidence that followers of pre-Christian religions existed in early modern Europe at all. Endre Bojtár, for instance, argued that we can know virtually nothing about pre-Christian Baltic religion because all we have are literary traditions of commentary on imagined religions, unmoored from reality.Footnote 72 In this conclusion Bójtar followed W. C. Jaskiewicz, who thought none of the Baltic religious and mythological information transmitted by sixteenth-century authors could be trusted.Footnote 73 In 1986 John van Engen came at this problem from a slightly different direction, arguing that Christianisation was successfully accomplished in the Middle AgesFootnote 74 – although it is important to note that Van Engen’s article was not focussed on the geographical ‘peripheries’ of Europe that are the subject of this book. This extreme scepticism is occasionally reflected in popular writing on the region; one recent writer took the view that

Almost everything that has ever been written about the ancient religion of the Balts and Slavs is false … Beyond the names of a few deities and a few scant archaeological remains, nothing is clear. So what can we say about these gods with certainty? Only three things: they lived in trees, they spoke through horses, and they savoured the smell of freshly baked bread.Footnote 75

Such flippant scepticism does little to dispel the prejudice that eastern European culture is without real value, and it promotes stereotypes every bit as much as a credulous embrace of the nationalistic excesses of the nineteenth century. The trend in more recent scholarship is towards a median between these two extremes of interpretation. For example, Darius Baronas and S. C. Rowell have argued that late medieval Lithuania was less ‘pagan’ than it is usually portrayed, but that ‘Orthodox’ Ruthenia was also more pagan than it appears; and while they are sceptical of the existence of temples in Lithuania, they do not deny the possibility of rural worship of spirits.Footnote 76 Similarly, the work of Siv Rasmussen on early Sámi religion has highlighted the extent of popular Catholicism in Sámi culture, which was often demonised as pagan by Lutheran missionaries; but Rasmussen does not draw the conclusion from this that Sámi pre-Christian religion did not actually exist in the early modern era.Footnote 77

Alexandra Walsham has argued that ‘the problem of pagan survival was in large part a semantic one’,Footnote 78 in the sense that one historian’s pagan survival is another’s deviant popular Christianity, depending on which argument the historian wants to make. There is some truth to this, and I would add to Walsham’s analysis that one country’s pagan survival is another’s deviant popular Christianity; in other words, folk customs are more likely to be interpreted as ‘pagan’ in a country whose conversion event occurred later. However, the notion of ‘depth of Christianisation’ is relevant here; while there is no reason why a fairly recently Christianised society cannot develop its own forms of deviant popular Christianity, it is highly unlikely that ‘pagan survivals’ can exist in a society deeply Christianised over the course of many centuries – and to claim that they can is an extraordinary claim, requiring extraordinary evidence. But the idea that the popular culture of a country whose Christianisation was accomplished only a few generations ago might be closer to its pre-Christians traditions is not prima facie implausible.

Like Baronas, Rowell, Rasmussen, Walsham, and others, I am conscious of the importance of acknowledging the potentially Christian or Christian-inspired character of early modern popular religion, even at its most deviant. Many accusations of ‘paganism’ arose from anti-Catholic or anti-Orthodox polemic. But the suggestion that pre-Christian religion did not exist anywhere in early modern Europe is no more plausible than the idea that every survival of folk culture encodes forgotten pagan rites. Christianisation is not an instantaneous process and not every author who recorded ‘pagan’ rites and beliefs did so with an overt religious agenda. None of the societies described by early modern antiquarians and ethnographers were untouched by Christianity; however haltingly and unsuccessfully, Christianisation had already begun, following a conversion event. Nevertheless, that Christianisation was also incomplete, which is why I propose the term ‘unchristianised peoples’ to refer to groups where pre-Christian religious outlooks and practices remained dominant (or continued alongside Christian practices).

Many of the conceptual difficulties associated with discussing ‘paganism’ in medieval and early modern Europe have arisen from a misplaced essentialism whereby Christianity and paganism are seen as discrete ideological opposites in a battle of ideas.Footnote 79 But rarely did the Christianisation process look like this; missionaries in northern Europe did not, like Paul of Tarsus in the Athenian Areopagus in Acts 17, address themselves to societies with highly intellectualised conceptions of reality. David Kling has argued that paganism, decentralised and non-hierarchical as it was, did not compete with Christianity for the same space in people’s lives.Footnote 80 Paganism and Christianity were mental worlds apart – which was a problem for Christianity as it sought to portray pre-Christian religion as a false belief it was replacing. But while the church was concerned with matters of identity, eternal salvation, and sacred authority, the cults and rites of the gods marked the ritual, natural, and agricultural years and were focussed on ensuring equilibrium between the divine, human, and natural worlds and the continuance of natural cycles. This was the ‘asymmetry … in the religious attitude’ of Christians and pagans that made both discussion and coherent conflict difficult.Footnote 81 The collision of Christianity and pre-Christian religions did not, in most cases, produce a battle of ideas, but resulted either in conversion (in responsive societies) or creolisation (in recidivist ones). It is those recidivist societies that are the focus of this book.

Sources and Hermeneutics

The principal sources for the study of pre-Christian religions in Europe between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries include chronicles, hagiographies of missionaries, ethnographic (or proto-ethnographic) and antiquarian writings, catechisms, ecclesiastical records dealing with discipline such as episcopal visitations, missionary reports, deeds of foundation of churches, judicial proceedings (for example, trials for witchcraft and sorcery), and, at a later date, the work of lexicographers. The authors of all these works were Christians, and antiquarians and ethnographers often worked from second- or third-hand reports on remote regions rather than relying on personal experience. However, it is undeniable that from the mid-fifteenth century onwards it became more common for ethnographic literature to be driven by curiosity as well as pious horror at pagan beliefs and practices. It is in this period, therefore, that we first have the possibility of glimpsing something of the reality of pre-Christian religions. On the other hand, as these chapters will explore, ethnographic and proto-ethnographic writings relying on hearsay and much older textual traditions were often much less immediate than disciplinary and judicial records. The disciplinary and judicial records, while clearly created with the intent of stigmatising and punishing pre-Christian beliefs and practices, were also written in response to specific infractions, and the level of detailed and geographically specific information they contain can therefore surpass the writings of the ethnographers.

All of these sources must be used with caution; they hold up a mirror to the anxieties of the Christian societies that produced them and the question of whether a reality of pre-Christian belief can also be glimpsed ‘through a glass darkly’ in that mirror is a fraught one. Furthermore, early modern writings tell us more about some aspects of pre-Christian religion than others; they are rich sources for reports of ritual practices, because these were the most visible manifestations of religion and were often reported by eyewitnesses, but it is much rarer for them to attempt to describe the mythologies or belief systems underlying ritual practice, or to give a detailed account of the material culture of pre-Christian religion.

In addition to establishing the limitations of the sources we have, it is also important to establish which alleged sources of evidence for pre-Christian religions are not, in fact, acceptable historical sources. In the nineteenth century, amateur and professional collectors began gathering, editing, and publishing tales, songs, dances, and customs from rural people all over Europe, resulting in a vast expansion in the body of apparent evidence for popular beliefs reaching far back into the past, owing to the early folklorists’ prevailing assumption that folk culture preserved immemorial – and probably pre-Christian – customs. As Margaret Murray confidently declared in 1921, in medieval western Europe ‘the mass of the people continued to follow their ancient customs and beliefs with a veneer of Christian rites’.Footnote 82 Similarly, the historian Geoffrey Coult insisted medieval women were crypto-pagans: ‘in church, the women crowded around Mary, yet they paid homage to the old deities by their nightly fireside, or at the time-honoured sacred haunts, grove or stone or spring’.Footnote 83 However, the idea that folklore collected in the nineteenth century (and later) constitutes a body of historical evidence for ancient belief systems has been largely discredited.Footnote 84

This is not to say that folklore is not important to the study of a culture, and Carlo Ginzburg warned that the rejection of ‘Murrayite’ excesses, such as Margaret Murray’s imagined Neolithic ‘witch cult’ surviving into early modern Europe, might produce a reaction that went too far towards scepticism. In some places in early modern Europe, agrarian fertility cults really did exist.Footnote 85 And while the existence of animist fertility cults in early modern Scotland or Italy is a claim requiring extraordinary evidence, the persistence of pre-Christian religion into modern times at Europe’s northern and eastern margins is less controversial – even if it is rather overlooked by many scholars. What is more controversial is whether folklore collected in the nineteenth century should be used as an interpretative framework for the scattered references to deities and rituals that appear in chronicles, missionary reports, and other sources before the nineteenth century. The pre-nineteenth-century evidence can easily become pieces of a puzzle to be slotted into a folklorically determined conception of what a particular people’s pre-Christian religion was like. At one level, this approach is not entirely unreasonable. Given that we have good reason to believe that unchristianised people still existed in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Sápmi as late as the eighteenth century, is it beyond the bounds of possibility that folklore collected in the nineteenth (and even twentieth) centuries has a chance of preserving some kernel of truth regarding the nature of pre-Christian religion? Certainly, it is more reasonable than folklorists in nineteenth-century England trying to reconstruct Neolithic fertility rites from Morris dancing.

However, one difficulty with the use of folklore collected from the nineteenth century onwards as a historical source is that it privileges folkloric material for its quantity and narrative coherence rather than for its closeness in time to the actual practice of pre-Christian religions. The methodology of the early folklorists was undoubtedly better than the haphazard way in which earlier authors recorded fragments of pre-Christian lore, but, crucially, the folklorists were living at a time when the practice of pre-Christian religions was essentially extinct – even if its extinction in a region like the eastern Baltic was much more recent than in Britain, Ireland, or Germany. The problem was the belief that folklore was full of ancient and immemorial survivals. Contemporary folklore studies, by contrast, emphasise the importance of human creativity and the creation of folklore as a continuous process, in contrast to an older ‘diffusionist’ view that legends and customs can only be passed from generation to generation indefinitely rather than being invented as the need arises.Footnote 86 It is thus the fragmentary evidence not systematically collected by folklorists but recorded at a time before successful Christianisation which, whatever its shortcomings, brings us tantalisingly close to the world of pre-Christian religions.

As the Latvian archaeologist Zenta Broka-Lāce has put it, ‘the use of [folklore] has always been treated with suspicion [by historians], because particular events and notions have arisen in different periods, so only in rare cases can folklore be directly linked to an actual timescale’.Footnote 87 In other words, folklore has an ahistorical tendency to ‘flatten’ the past (treating all mythological data, from any era, as equal), thus removing most of the meaningful historical data. This ‘flattening’ of the past is exacerbated by a prevalent assumption that pre-Christian religions were deeply conservative and did not change over time. This is an especially problematic assumption given the profound impact of contact with Christianity on many pre-Christian religions. The role of the nineteenth century in forming our perceptions of ‘paganism’ will be explored in detail in Chapter 6, but the historian dealing with a period before the nineteenth century cannot afford to rely on speculations founded on nineteenth-century folklore-collecting, however diligent. Nineteenth-century folklore tells us a great deal about the nineteenth century, and perhaps even the eighteenth; whether it has anything reliable to tell us about earlier eras is something on which the historian must suspend judgement.

Just as folklore is not a historical source, comparative mythology grounded in historical linguistics and Indo-European studies cannot be treated as a historical source either. The example of Dievas/Dievs, the ‘supreme god of the Baltic pantheon’, illustrates some of the difficulties. Dievas/Dievs is, of course, the Lithuanian/Latvian word for ‘God’, referring in modern Baltic languages to the Christian God. While the ancient Balts may well once have worshipped a sky god named *Deivas, on the basis that this theonym is cognate with numerous other Indo-European words (like Latin deus), there is no actual documentary evidence for a Baltic god Dievas/Dievs – an absence explained away by some earlier mythologists on the basis that Dievas/Dievs was identified early on with the Christian God. We thus have a historical claim being made (that Christian missionaries took a pagan sky god, Dievas/Dievs, and identified him as the Christian God) on the basis of the absence of textual evidence.Footnote 88 This is not an acceptable methodology for the historian. We cannot make large assumptions about pre-Christian religion purely on the basis of linguistic and comparative mythological suppositions, which risk creating mirages with no real attested existence like the alleged Baltic sky god. What we can say with certainty, on the basis of Baltic folklore and folk song, is that modern Balts formed their own folk conception of the Christian God (Dievas/Dievs), which may or may not have been influenced by the persistence of elements of pre-Christian belief, poor catechesis in the Christian faith, or both.Footnote 89

Unfortunately, the temptation to privilege folklore as a historical source for pre-Christian religions was for too long indulged by a historiography that threw the net too wide in the search for ‘pagan survivals’. If any expression of popular religion that deviates from officially sanctioned Christianity is deemed ‘pagan’, if folk medicine is deemed ‘pagan’, if seasonal folk customs are deemed ‘pagan in origin’, if any folktale can be reinterpreted as a degenerated pagan religious myth – then ‘paganism’ is everywhere, to the point that distinguishing a people’s pre-Christian from their Christianised culture is scarcely meaningful at all. The hermeneutic of ‘pagan survivalism’ in ethnography and folkloristics, which was dominant for over a century between the mid-nineteenth and mid- to late twentieth century, was underpinned by a prevailing assumption that folklore was very old. If the memory of the folk retained data from the distant past, that data was in all likelihood ‘pagan’ – and the more recent the Christianisation of a particular people, the more likely it was that folklore testified to a ‘pagan’ substratum of ritual and belief. I have referred to this tendency elsewhere as ‘pagans under the bed’:Footnote 90 the belief that pagans and paganism are to be found everywhere in European culture, if only we look closely enough.