Introduction

The impact of urbanisation and urban migration is far-reaching globally. The urbanisation process creates dramatic macro-social changes in employment structures, income disparities, housing and transportation demands within urbanised spaces. Meanwhile, rural villages and communities are left to deal with out-migration that leaves behind skipped-generation families living in deserted and untilled lands; the social changes coming along with urbanisation in China are drastic and rapid. While urbanisation in Western countries occurred at a relatively slow pace, taking roughly 100 years in the United States of America (USA) for the urban population to increase from 10 to 70 per cent from the 1840s to the 1970s, China saw rapid urbanisation in just 30 years, with its percentage of urban population growing from 10 to 60 per cent between 1980 and 2010 (US Census Bureau, 2006; Zhan, Reference Zhan2011). China's rapid pace of urbanisation has created a structural lag in its urban areas; housing, employment, pension and health-care reforms have been unable to meet the needs and demands of the country's growing urban population. Meanwhile, there is an emerging cultural and structural lag in rural China as the long-held tradition of filial piety, known as xiao, is disrupted by the emerging skipped-generation families. Skipped-generation families are households in which grandchildren live with grandparents without the presence of a parent (Mills et al., Reference Mills, Gomez-Smith and Leon2005); these families are often the result of out-migration of the middle generation in the pursuit of better employment through migrant or urban work. To understand the cultural and structural lagging, one has to first understand the Chinese cultural traditions and structural changes that face major challenges as a result of urbanisation.

The foundational Chinese cultural tradition is best known as the Confucian doctrines of filial piety. The Confucian doctrines of filial piety dictates and harmonises social and familial relations by emphasising the importance of intergenerational relations. Parents are to be loving and benevolent (仁慈) to children; children are expected to respect and obey parents (孝顺) while they are young and take care of ageing parents financially, emotionally and physically when parents become frail and dependent (Sher, Reference Sher1984; Zhan and Montgomery, Reference Zhan and Montgomery2003). This cultural norm has functioned as a behaviour code between generations for thousands of years. Under Communist China, children's care for parents is further codified into the law by punishing those who fail to provide and care to ageing and frail parents as a punishable crime (Streib, Reference Streib1987; Ikels, Reference Ikels1993). Because Chinese families have traditionally been patriarchal and patrilocal, the care for ageing parents typically is provided through sons’ family, often by daughters-in-law. Even though recent research has noted an increasing involvement and share of responsibilities of daughters in the care for ageing parents in urban China (Zhan et al., Reference Zhan, Feng and Luo2008), rural families have continued to be more patriarchal and patrilineal in this practice (Silverstein et al., Reference Silverstein, Cong and Li2006). When large numbers of youngers have migrated to urban China for better job opportunities, the rupture of this Chinese tradition leads to the lagging of this intergenerational exchange.

Furthermore, China is experiencing an unprecedented demographic change. Chinese baby-boomers, born between 1950 and 1979, are rapidly entering retirement age. In 1950, according to the United Nations’ (2000) World Population Prospects, China's life expectancy at birth was 43 years; in 2020, people in China are expected to live to 77. With longer life expectancy, the proportion of older people has also been rapidly increasing. While it took France 115 years to double the 65+ age group from 7 to 14 per cent of its population, only 23 years were needed to do so in China. By 2035 the population aged 65+ in China will triple and constitute 21 per cent of the total population (He et al., Reference He, Goodkind and Kowal2016). Most of its ageing population resides in rural China: in 2000, 7.33 per cent of the total rural population were 65+ compared to 6.3 per cent in urban China (Zhou, Reference Zhou2004; Fan and Wu, Reference Fan and Wu2005; Gu et al., Reference Gu, Dupre and Liu2007). By 2015, 60+ older adults residing in rural China accounted for 17.7 per cent of its rural population while older adults accounted for 14.97 per cent of China's urban population (National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China, 2015a). This percentage is based on residential registration (hukou or 户口) of the citizen's birthplace. According to China's rural migrant workers survey report, there were 277.47 million rural migrant workers who resided in urban areas in 2015; these migrant workers made up 45.9 per cent of the total rural population registered through hukou (National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China, 2015b). Consequently, the rural elderly population accounts for 32.68 per cent of the actual population residing in rural areas along with grandchildren, women with children and a small percentage of rural workers. Unlike most ageing societies in welfare states where older adults enjoy pensions, medical care and long-term care insurance, China is still developing pension and medical care systems in much of its rural areas while the nation continues to depend on families to serve as the prominent provider of long-term care. When large numbers of the middle generation have migrated away from the home villages to urban areas to work and reside, how is this Confucian culture of filial piety going to continue?

Census data can only provide a broad and quantitative understanding of urban migration rates; such general details cannot possibly depict the lived experiences of China's rural families in the wake of the country's rapid urbanisation and population ageing. This paper contributes to the limited literature by painting a vivid picture of this cultural rupture in interior China's rural communities with much-needed qualitative evidence.

Literature background

Intergenerational exchange of support is common across the globe; however, the forms of this support varies. In developed societies where welfare states are strong, intergenerational support among families with three or more generations (i.e. grandparent, parent and grandchild) widely reflects a net-downward flow of resources. In other words, older generations provide more support to their children and grandchildren than they receive (Grundy, Reference Grundy2005; Litwin et al., Reference Litwin, Vogel, Künemund and Kohli2008). Such support can take on various forms, including financial support, child care, household assistance and emotional support (Hogan et al., Reference Hogan, Eggebeen and Clogg1993).

In China, studies from the 1990s found the practice of filial piety remained widespread in urban and rural families, with children financially and physically supporting their ageing parents (Lavely and Ren, Reference Lavely and Ren1992; Goldstein and Ku, Reference Goldstein and Ku1993; Zhan and Montgomery, Reference Zhan and Montgomery2003). In recent years, however, the need for this support has decreased in urban China, where growing numbers of urban retirees have become financially independent on account of substantial pension and retirement benefits (Zhan et al., Reference Zhan, Feng and Luo2008, Reference Zhan, Feng, Feng and Chen2011). The demand for adult children's hands-on care has also declined, as an increasing number of urban elders move to long-term care homes. The script of filial piety in urban China has shifted to include institutional care, while adult children continue to provide emotional care and financial assistance, as needed (Zhan et al., Reference Zhan, Feng, Feng and Chen2011). Filial piety remains integral for elders in rural China, where retirement funds are minimal. In rural Shandong province, for example, 75 per cent of adult children continue to provide financial support for their ageing parents (Zhong et al., Reference Zhong, Lu and Wei2015). Xu (Reference Xu2001: 311) describes rural parents’ continued reliance on adult children as a gendered phenomenon: with sons as their ‘pensions’ and daughters as ‘bonuses’. When rural elders can no longer rely on their own labour, due to frailty or illness, adult children assure their welfare.

The research on adult children's support for their ageing parents in China has been prolific, likely a product of the cultural emphasis on filial piety. As urbanisation has decreased the need for the upward flow of financial support from children to their older parents in urban areas, some parents have begun to direct their own resources down to support their adult children. Yet, there remains a dearth of literature on the downward support Chinese parents provide to their adult children and families. Further investigation is needed to understand how support continues to flow in China's rural communities.

Descending support in developed welfare states

Understanding intergenerational support in developed and welfare states may shed some light on understanding the intergenerational support patterns in China. In terms of financial support, older generations provide substantial support to their children, particularly to attend college and purchase their first home. This phenomenon has been observed in different countries; however, the extent of this support varies by wealth and nationality (Ronald and Lennartz, Reference Ronald and Lennartz2018). In the USA, parents’ financial support largely covers the cost of their children's college education: an estimated 70 per cent of college costs are paid for by parents (Sallie Mae, 2014). As young adults experience increasing difficulty entering housing markets, their parents’ support includes down-payments or signatures to serve as guarantors for their children's home mortgages (Köppe, Reference Köppe2018). Parents with higher incomes and levels of education typically provide more financial support for their children (Faber and Rich, Reference Faber and Rich2018; Haider and McGarry, Reference Haider and McGarry2018). Meanwhile divorced and uninvolved parents typically provide less financial support (Han, Reference Han2018). Additionally, parents serve as financial safety nets, as is the case with co-residential support, where children live rent-free in their parent's homes in order to save for their own homes (Köppe, Reference Köppe2018) or during times of financial strain and divorce (Santoro, Reference Santoro2014).

Child care is another major form of downward support provided by older generations in the USA. This support is more common around the time a new grandchild is born, or when adult children live nearby, compared to those who do not live nearby (Uhlenberg and Hammil, Reference Uhlenberg and Hammil1998; Michalski and Shackelford, Reference Michalski and Shackelford2005). When three generations co-reside, grandparents are most likely to invest time in both child care and housework while their adult children work outside the home (Hărăguş, Reference Hărăguş2014). This downward support of grandchild care can vary in regularity (scheduled, unscheduled) and form (time, monetary). As grandparents age, their health, financial stability, lack of social or familial support, as well as challenges in grandchildren's behaviour and health problems, may lead ageing grandparents to experience higher levels of stress and care difficulty; in turn, this may lead to a rapid decline of physical and mental health for some grandparents (Sand and Goldberg-Glen, Reference Sand and Goldberg-Glen2000; Kelley et al., Reference Kelley, Whitley and Capos2010; Sprang et al., Reference Sprang, Choi, Eslinger and Whitt-Woosley2015).

Provision of downward support across developed societies is not monolith. Countries with strong national social welfare programmes, such as child-care programmes, allow grandparents to provide alternate or complementary support to younger generations, such as financial support or assistance with housework (Igel et al., Reference Igel, Brandt, Haberkern and Szydlik2009). Family structure and size also have an influence on support provision. Parents who are widowed or divorced are less likely to provide support to their children (Eggebeen, Reference Eggebeen1992). Additionally, the number of children a parent has can limit the amount of support provided to each individual child (Hogan et al., Reference Hogan, Eggebeen and Clogg1993). Parents with step-children are less likely to provide support to all children as the proportion of step-children in their families rise (Eggebeen, Reference Eggebeen1992).

The gender of parents and children can also influence the provision and implications of intergenerational support. Analysis of time-use data among Australian households found that grandmothers are more likely to provide child care for their grandchildren, compared to grandfathers. Grandmothers who regularly provide grandchild care tend to report higher time pressures and less time for personal care and sleep, compared to grandmothers who are not regular care-givers, whereas the regularity of grandfathers’ child care was not associated with these pressures (Craig and Jenkins, Reference Craig and Jenkins2016). In the USA, maternal grandmothers are more likely to be involved in child care for their daughters’ children (Goodsell et al., Reference Goodsell, James, Yorgason and Call2015). Such gendered support has been found to vary among racial and ethnic groups, with adult African-American parents receiving more downward support from their direct-maternal family members (e.g. mothers and grandmothers), compared to Hispanic parents who receive intergenerational support from a larger extended-kin network, including both their mothers’ and fathers’ families (Haxton and Harknett, Reference Haxton and Harknett2009). Among adult children who receive support, gender also matters. Based on a study by Haxton and Harknett (Reference Haxton and Harknett2009), men, compared to women, were less likely to receive financial and housing support from family. Additionally, the gendered make-up of families with multiple children impacts the downward flow of support: Goodsell et al. (Reference Goodsell, James, Yorgason and Call2015) found that the number of sisters an adult child has is associated with decreased odds of receiving support from older parents.

Older generations in developed societies provide financial support, daily assistance and child care for younger generations. Do younger generations return with ascending support when parents grow older and physically dependent? It is widely known that welfare states provide financial stability through Social Security or pensions for older adults. Medical care is provided through systems such as Medicare in the USA, while long-term care insurance is established in nations such as Germany and Japan to ensure end-of-life care. These welfare states have taken over most, if not all, filial responsibilities for ageing parents.

With few ageing-care obligations placed upon younger generations, is the intergenerational bond weakening? Prolific research has shown that the family value and bond is not declining in the USA (Bengtson, Reference Bengtson2001; Hartnett et al., Reference Hartnett, Fingerman and Birditt2018; Fingerman et al., Reference Fingerman, Huo and Birditt2020), rather, it remains strong – not by obligation, but by choice. In Germany and Scandinavian countries, family members are compensated for the care of their ageing parents (Whittington et al., Reference Whittington, Kunkel and de Medeiros2019). This practice increases the quality of life for both the young and older generation so that the older generation can live at home longer and the younger generation can have their care work compensated so that they can be financially independent. How is China's urbanisation and rapid pace of population ageing influencing intergenerational contract of care?

Intergenerational exchange – theory and practice in China

Exchange theory is rooted in economics, with the assumptions that resources are generally unequal across individuals and that people with varying resources will engage in exchange only if the benefits are equal to, or greater than, the costs. In intergenerational exchange, the longstanding Chinese Confucian tradition of ‘raising sons for old age’ represents a typical practice of exchange theory within the family that has held the family together as an intergenerational contract. Parents raise their children, provide food, clothing and housing, and care for them until they get married and, in return, children, especially sons, are expected to provide care for their parents as they become more dependent in old age. This practice is normalised in Confucian culture and even codified in law in Communist China. Soon after the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the constitution of the PRC in 1954 stated that ‘Parents have the duty to rear and educate their minor children, and the adult children have the duty to support and assist their parents.’ In the penal code of 1980, the amendment established that children can be imprisoned for up to five years for neglecting their parents. In 1996, the Law of Elders’ Rights and Protection (老年人权益法; http://www.npc.gov.cn) officially enforced adult children's obligation to respect and take care of their ageing parents physically, financially and emotionally. The law formally regulated adult children's provision for ageing parents in terms of housing, medical care, property protection, and so on. These laws regulated not only sons’ but also daughters’ filial obligations towards elderly parents. As a result of this enforcement, elderly parents in China have often become characterised as care recipients rather than care-givers. Little attention is given to ageing parents’ efforts in support of children in the later years of their lifecourse. Ageing parents’ support for adult children is often provided through financial and child-care support, which are driven by patrilocal traditions.

In Chinese tradition, when a woman marries into a man's family, her husband's family is expected to provide housing (patrilocal tradition), because marriage serves as a continuation of the paternal family's bloodline (patrilineal). Parents of sons are continually expected to adhere to these patrilocal and patrilineal traditions. In contemporary China, descending financial support typically includes parents purchasing a flat in urban China or building a house in rural China for adult sons when they marry (Wang, Reference Wang2014; Wei and Jiang, Reference Wei and Jiang2017). As a result of urbanisation, housing prices have risen rapidly in the last few decades (Zhong, Reference Zhong2015; Chen, Reference Chen2017), leading young couples to draw increased financial support from their parents to afford a residence in urban areas. This has left parents bearing the pressure of increasingly costly housing needs as they fulfil traditional care expectations for their children. Child-care centres are available, but often costly, in urban China, which has also led many young couples to turn to their parents for assistance with child care. Research has shown that paternal grandparents’ households remain a popular destination for such child care (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Liu and Mair2011).

Few studies on the downward flow of intergenerational support in urban China have investigated possible gender differences in the support given to sons and daughters, likely due to the history of the one-child policy. In families with only one child, regardless of their child's gender, ageing parents may devote all their resources to the wellbeing of their only child and their partner's only child. In rural China, where families were permitted to have multiple children throughout the duration of the one-child policy, patrilocal and patrilineal traditions may continue to influence patterns of intergenerational support.

Descending support in rural China

Descending or downward flow of support in rural China has revealed a much more complicated storyline compared to that of urban China. Many rural elderly parents expect to live with their adult sons in later life (their oldest son, in particular), thus elderly parents taking the responsibility for providing housing for their adult son's marriage also has become a norm in rural China (Short et al., Reference Short, Fengying, Siyuan and Mingliang2001; Goh, Reference Goh2006). Once co-residing, maintaining the home and providing child care in the household become a joint task between adult children and their elderly parents. The demand for rural grandparents to provide child care has also been increasing in recent years, particularly among families whose sons take on migrant work and are unable to participate in child-rearing (Cong and Silverstein, Reference Cong and Silverstein2011). In the past three decades, over 220 million rural labourers migrated to urban cities, which resulted in an estimated 58 million rural children left in the care of grandparents and rural communities (Cong and Silverstein, Reference Cong, Silverstein, Mehta and Thang2012). Many grandparents in rural China lack the necessary resources to provide child care, thus opening both elders and their grandchildren to potential adverse outcomes (Silverstein and Cong, Reference Silverstein and Cong2013). The burden of providing ongoing financial and physical support eventually leads to serious health problems among rural Chinese elders (Chen and Liu, Reference Chen and Liu2012; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Chi and Silverstein2013, Reference Guo, Chi and Silverstein2017).

Excessive downward flow of support from elderly parents demanded by their adult children creates an intergenerational exchange gap. Several scholars have labelled such disproportionate flow of support as ‘intergenerational exploitation’, where elderly parents receive little or no reciprocation of physical, emotional and financial care from their adult children (Liu, Reference Liu2012; Wei and Jiang, Reference Wei and Jiang2017; Lu, Reference Lu2015). Previous research has identified macro-level factors (particularly issues stemming from urbanisation) that have contributed to the emergence of such ‘intergenerational exploitation’. Yan (Reference Yan2011) has argued from the perspectives of cultural value change. In the qualitative research, Yan argued that Chinese modernisation and Western cultural influence have resulted in the ‘individualisation’ of Chinese families. This ‘individualisation of the family’ is best represented in the ‘disembodiment of the individual’ from ‘the patriarchal order’ (Yan, Reference Yan2011: 208). Simply put, the younger generation in rural China is no longer bound by the social contracts of Confucian culture. These younger generations are more likely to choose their own marriage partners instead of accepting arranged marriages and seek to establish nuclear families away from their parents (Yan, Reference Yan2003). Consequently, ageing rural parents are more likely to live in their ‘empty nest’ and less likely to have adult children's direct support. In rural families where most male children become migrant labourers outside the village, many rural elder adults are left behind, raising grandchildren, experiencing a ‘lone sunset’ in their old age (Ye and He, Reference Ye and He2008) or living in skipped-generation families (Luo and Zhan, Reference Luo and Zhan2012).

Using national survey data, Fang et al. (Reference Fang, Giles, O'Keefe and Wang2012) have shown that the living arrangements for Chinese rural elders illustrate a pattern of declining intergenerational co-residence, increasing empty nest households. The presence of adult children living nearby, rather than in the same household, however, remains common. As age and dependency levels increase, rural elderly parents become more vulnerable. Poverty level increases with age among rural elders. Having more children and migrant workers in the family tend to reduce the levels of old-age poverty for elders. A third of urban elders receive income from other family members, mainly children; meanwhile, over half of rural elders relied on their families for financial support. Rural women, in particular, report the greatest dependence on children: 68 per cent of rural women age 60+ exclusively rely on children's financial support (Fang et al., Reference Fang, Giles, O'Keefe and Wang2012).

Using longitudinal qualitative research, Yan (Reference Yan2016: 245) has portrayed a more positive picture of the Xiajia village in north-eastern China. In Xiajia village, the descending intergenerational exchange results in ‘consensual solidarity’ in which filial piety is redefined to be filial respect without unconditional obedience. Yan found that adult children's appreciation for their ageing parents developed as they raised their own children. The shared goal of raising an “exceptional” third generation, thus, reunites adult children and their ageing parents. Even though many families continued the renewed sense of filial piety, some rural families rejected the tradition, even filing for divorces due to intergenerational conflicts (Yan, Reference Yan2015).

When children fail to provide financial or physical care in rural China, a qualitative investigation by Xu (Reference Xu2001) explains, an influential extended family member or village cadres (i.e. local government leaders) usually step in to intervene. Following the end of agricultural taxation in rural China in 2006, however, local rural governments have lost the resources to provide education, medical care and other rural welfare programmes (http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2005-12/31). In addition, declining administrative powers of village cadres has lessened the impact of social sanctions against village members who fail to support their ageing parents financially and physically (Ye and He, Reference Ye and He2008; Yan Reference Yan2011).

In 2007, the Chinese central government started the minimum guaranteed income for rural elders living below the poverty line. In 2018, 39.4 million people in rural China were defined as living below the poverty line. Among them, an estimated 14.94 million were older adults, that is 37.9 per cent of its total. The national average for minimum monetary of income support was 4,833 yuan (or US $690) per year, averageing 402 yuan (or US $57) per month in 2018. Despite regional differences in support, this income would barely cover the costs of food in most households. When additional expenses, such as medical care costs, occur, rural elders become even more vulnerable and must rely on their adult children or other family members to cover these expenses.

Are adult children available for the financial and physical support for their ageing parents? With nearly half of rural population migrating to urban areas for better work opportunities, how is the cultural contract of intergenerational exchange holding up in the wake of China's rapid urbanisation and population ageing? Using qualitative interviews with 50 rural families in Anhui Province, China, this study contributes to the existing body of literature that understands how this intergenerational exchange, or exploitation, emerges within the descending flow of support from older parents to adult children in rural China.

Methodology

Sample and research site

Data for this analysis are taken from ‘The Research of the Livelihood of Rural Migrant Workers and Their Sustainability’, which was funded by the Chinese National Social Science Foundation. The goal of the research was to understand the exchange of intergenerational support within families in rural China. This research is based on participant observation and interviews taken in Lee Village in Sixian, Anhui Province, China, between August 2017 and December 2018.

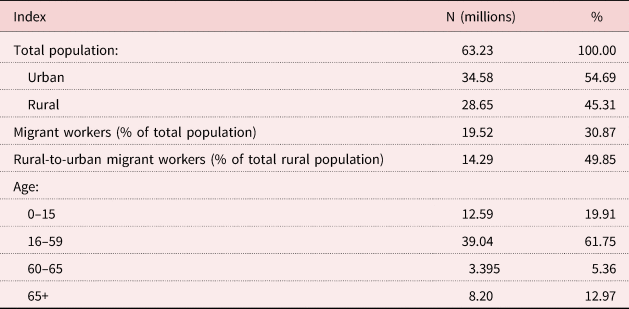

Anhui Province lies in the interior of China, with Sixian being a county in north-east Anhui Province. This part in the interior of China is economically underdeveloped. Most residents have traditionally relied on agricultural farming, however, increasing numbers of farmers are making a living as migrant workers. Anhui Province had the eighth largest population with 63.23 million permanent residents, accounting for 4.5 per cent of China's total population (Table 1). The province's population aged 65+ totalled just over 8.20 million, accounting for 12.97 per cent of the total province population (Statistics Bureau of Anhui Province, 2018). A little over half of the province's population lived in urban areas (54.69%), while the remainder (45.31%) are registered as rural residents (Statistics Bureau of Anhui Province, 2018). It is important to note that the Chinese hukou (residential registration) system does not reflect well the positioning of rural migrant workers in urban areas; while these workers may currently reside and work in cities they are registered as rural residents (Lu, Reference Lu2008). In 2018, there were 19.52 million migrant workers in Anuhi Province. Among them, 14.29 million (or 73%) are rural-to-urban migrants (Statistics Bureau of Anhui Province, 2018); adding this rural-to-urban migrant population into the count of urban residents, in Anhui Province alone, the urban residents make up effectively 77 per cent of the total population. These trends in out-migration have disrupted the rural family structure, leading to many rural grandparents caring for grandchildren without parents present.

Table 1. Population of Anhui Province at the end of 2018 and its composition

Source: Statistics Bureau of Anhui Province (2018).

At the end of 2018, Sixian's registered population totalled 961,100, the majority of whom were rural residents (78.43%). The per capita disposable average annual income of both urban and rural residents was 15,728 yuan per year (roughly US $2,247). The per capita disposable income of urban residents was 27,217 yuan per year (roughly US $3,888); that of rural residents was 11,455 yuan per year (roughly US $1,636) (Statistics Bureau of Sixian, 2018). The county's population is distributed across 222,635 households. Sixian was nationally designated as a poverty-stricken county due to its underdeveloped economy. Even though the number of people living below the poverty line declined from 101,400 in 2012 to 65,400 in 2014 (Sixian, 2020), the poverty rate is still relatively high. Sixian is considered to be a major labour export county as many adults take on urban and migrant work.

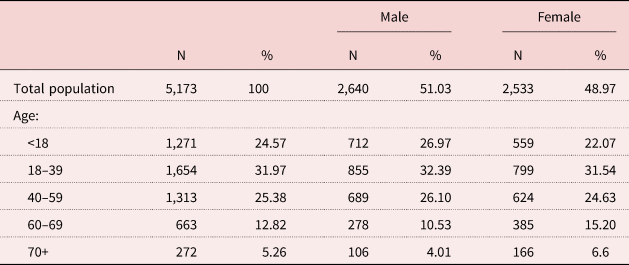

Lee Village is an administrative unit in Sixian, with a population of 5,173 people from 1,263 households (Table 2). Based on the 2018 Census Department of Sixian, one-quarter (24.57%) of Lee Village residents were children under 18, less than one-third (31.97%) were adults between the ages of 18 and 39; adults between 40 and 59 accounted for 25.38 per cent; 12.82 per cent were older adults ages 60–69; and only 5.26 per cent of elders were aged 70 and older in Lee Village (Police Office in Sixian, 2020). According to a local village official's estimate that the vast majority, roughly 90 per cent, of able-bodied young and middle-aged adults have become migrant workers outside the village. The elders and children are left behind in the village, relying on income from either local agricultural farming or wages sent home from migrant family workers.

Table 2. Demographics of Lee Village in 2018

Note: Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

Source: Census Department of Sixian, Anhui Province, China.

Data collection

This paper's primary author spent over one year in Lee Village to conduct research through participant observation and intensive interviews. A total of 85 elders or older parents and 20 adult children from 50 families were interviewed. Most interviews were obtained via snowball sampling, while interviewees were initially identified by the primary author during the participant observation activities. Interviews were mostly conducted in the homes of the participants, ranging in length from half an hour to two hours. In the cases where multiple family members were present at home, the interviewer attempted to conduct interviews with individuals separately in order to avoid discomfort or dispute. Oral consent was obtained before each interview started. Interviews were not recorded to avoid rural participants’ discomfort with video or audio taping; the researcher completed field notes soon after each interview concluded. In addition to interview notes, the senior researcher collected over 320 pages of field notes as part of the research. These notes included conversations with neighbours of the interviewees and village cadres, and general comments made by villagers.

Data analysis was performed by the principal researcher who conducted the interviews. Emerging concepts and themes were reviewed and discussed on a weekly basis with the second author, using grounded theory methods (Strauss and Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998). After the initial coding, we reviewed the emerging concepts and combined similar concepts into themes to generate a higher level of understanding. Following the identification of key themes, we compared the relationships between the themes and frequencies of concepts, in what Strauss and Corbin (Reference Strauss and Corbin1998; Corbin and Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2015) called axial coding. In the presentation of our data, we describe three areas of intergenerational support transmission: (a) the descending transfer of financial support, (b) the descending transfer of child-care support, and (c) upward transfer of support. In the process of this presentation, a clear gap of exchange between generations emerges, through which we find the cultural lag in the intergenerational exchange in rural China.

Description of the sample characteristics

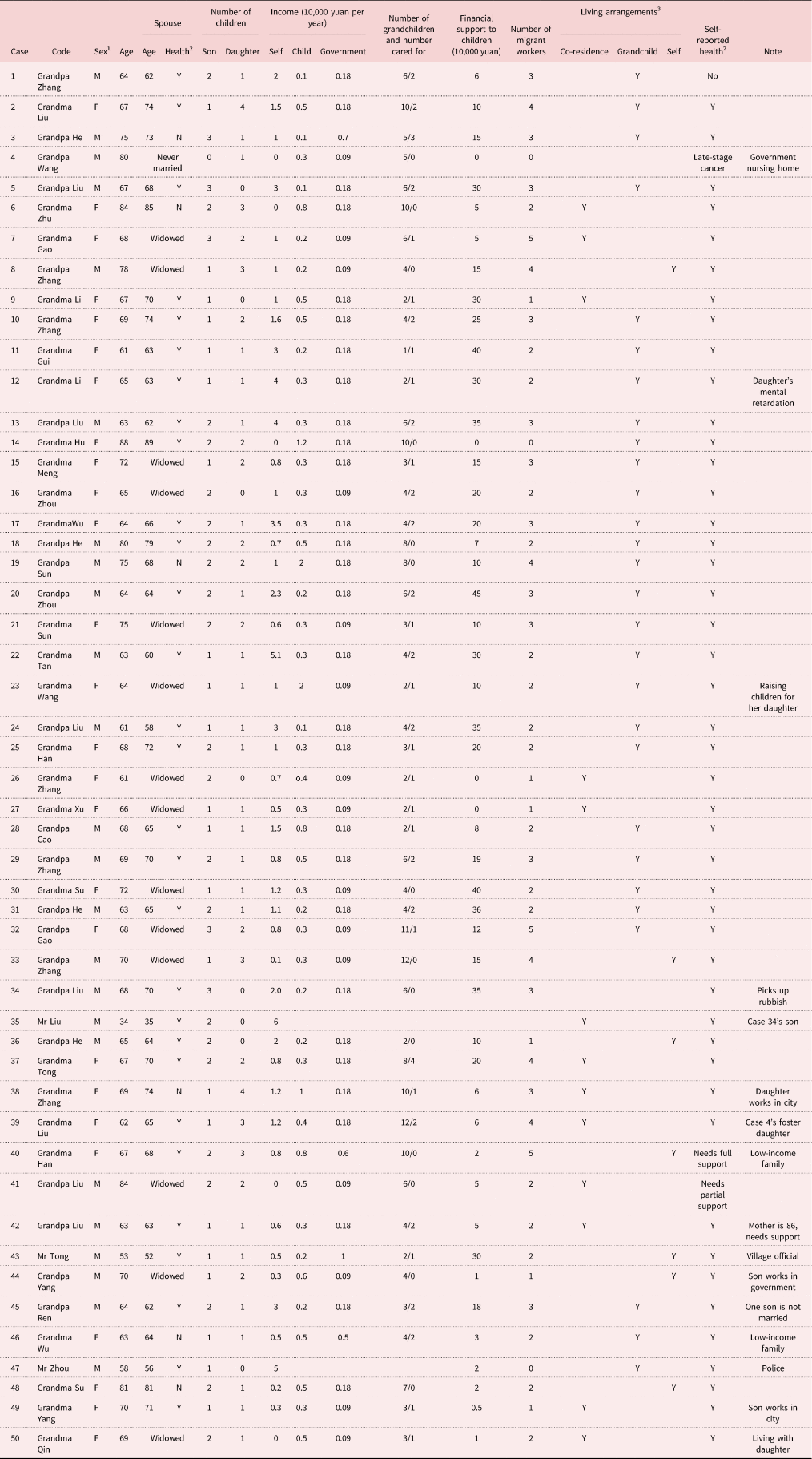

Among the interviewees in the 50 families sampled, 26 were women and 24 were men. The majority of interviewees (32) were aged between 60 and 69, nine were between 70 and 79, and six were 80 or older (for details, see Table 3). The majority of participants were married (35), 14 were widowed and one participant was never married; most of the elders (three-quarters) lived with their spouse or alone. Thirty-four elders reported they were taking care of grandchildren, either living in their adult children's home or having grandchildren living with the grandparent. Among these households, the majority (29 of 34) were skipped-generation families. As is common in Lee Village, middle-aged adults were rarely available to participate in the study, as most had travelled outside the village to seek migrant work. The very few younger adults who stayed behind in the village did so in order to care for their own young children, ageing parents or parents-in-law. Four participants co-resided with their daughters-in-law, who earned money handknitting or weaving while taking care of their own children alongside their elderly parents-in-law.

Table 3. Demographic descriptions of participants

Notes: 1. M: male; F: female. 2. Y: healthy; N: not healthy. 3. Y: yes.

Interestingly, one grandparent couple chose to live separately part-time, allowing the grandmother to co-reside with her adult child's family and to help raise grandchildren in the city; meanwhile, the grandfather remained in Lee Village full-time, living by himself. Only one participant had no adult children to rely on; this man resided in an elder-care home funded for childless elders by the government.

The vast majority of participants continued to rely on their own farming or labour to survive, either farming in the village or doing seasonal migrant work. Only five reported having no income, as they were unable to work due to ageing and frailty; these elders relied entirely on support from their children or government welfare. From a programme beginning in 2009, rural elders aged 60+ received a ‘Basic Retirement Pension’ of 75 yuan per month from the government, totalling 900 yuan each year. Though the amount of government support is meagre, it does help the rural elders to have the very basic income to survive. Despite meagre government support and personal incomes, older rural parents continue to shoulder heavy financial burdens to provide ongoing support to their children.

Findings

Qualitative findings are presented in three themes. The first two themes focus on the downward provision of support through financial transfers and child care provided by ageing parents. The third theme describes the ascending support from adult children to their ageing parents.

Descending transfer of financial support

Based on participant observation and intensive interviews, our findings reveal financial support often comes in the form of constructing or building a new home for children, almost exclusively for sons. The patrilocal marriage custom in rural Anhui Province is such that the groom's parents are expected to build a house, if living in a rural area, or purchase a flat in urban areas as their sons prepare to be married. Among the families interviewed, only four participants reportedly did not provide financial support for their children's housing. Based on reports from the majority of interviewed elders, the financial cost to support their adult children in obtaining housing ranged between 10,000 and 400,000 yuan (roughly US $1,400–57,000). A migrant labourer earns roughly 100 yuan a day by making bricks or doing construction work. After paying for rent and food, a migrant labourer may save $10,000–20,000 after a year of migrant labour. For parents with a single male child, the ability to build or purchase a house as part of their son's wedding may be a joy; however, for rural couples who have several sons to prepare for marriage, the financial pressure can be immense and burdensome.

Grandpa Liu, age 68, and his wife, age 70, have three sons and no daughters. To prepare for their first son's marriage, they built a small house costing them 180,000 yuan (roughly US $25,700); some of this money was borrowed from extended family members. When the couple could not earn enough money through their farming to pay off the debt, they decided to migrate to Xiamen, a coastal city cross the strait from Taiwan. The couple worked during the day and collected garbage in the evenings to sell for additional money. They accounted:

Before we were able to pay back the loan fully for our first son's house, our second son was on his way to get married. We then had to migrate to work and sell garbage again in order to accumulate more money. By the time our third son proposed to get married, we told the future daughter-in-law: ‘In five years, I promise we will build you a new house for your marriage.’ Only in this way the young woman was willing to marry into our family. It is not until a few days prior to this interview did we finally pay back the loans for the three houses.

In some cases, parents’ intensive efforts to secure a house for their sons and future daughters-in-law seemed to be taken for granted. When interviewing the Liu's first daughter-in-law, she explained:

I made it clear before marriage that I have to have my own housing to live. I also made it clear before marriage that after marriage, my husband and I will have our own separate finances. We don't want to use our income to pay his parents’ debt. When we make money as migrant workers, that is our money. Otherwise, we will forever be poor. Also, we have two sons now, we will have to prepare for their housing for their future marriages.

As seen in the daughter-in-law's expectations, family finances are becoming ‘individualised’, focusing on the nuclear family, reflective of the findings in Yan's (Reference Yan2003, Reference Yan2011) research. The younger generation appear to be more focused on their small family. They take the patrilocal family tradition as a norm, explicitly expressing the expectation of financial support from the groom's family. Meanwhile, the daughter-in-law wanted to have separate finances because when she and her husband make money, ‘it is our money’. In this intergenerational relationship, the older generation is primarily giving, while the benefiting adult children indicate little intention to ‘share’ or give back after marriage, according to the daughter-in-law.

In the He family, the financial burden from two sons was slightly lighter than the Liu's. Both Mr He, 65, his wife, 64, never received a formal education. They had two sons, one received college education and found a job in a nearby city while the other had been employed as a migrant worker. In order to help their migrant worker son to purchase a flat in an urban area, Mr and Ms He leased their land in Lee Village for 10,000 yuan and temporarily relocated to an urban area to begin migrant work. Working as a construction worker or brick maker, they each could earn roughly 100 yuan per day. By the end of the year, they saved 30,000 yuan between the two for their son's flat. ‘With the money we saved, we can help our son to afford a flat in an urban area. Only in this way, can he afford to survive in urban China.’

Among the 50 families studied, all parents expressed the norm of parents to financially support their sons in preparing housing before marriage. Patrilocal tradition induces the cultural norm of sons’ expectation for parents’ financial investment, but not for daughters. In rare cases parents described financially supporting their daughters. When they did, their effort appeared to be challenged by their sons. Grandma Zhang, 69, and her husband, 74, had one son and four daughters. The son was the oldest. When their first daughter went to college, the parents helped her financially. Grandma Zhang recollected:

Our son was not happy, he complained that we put all our money into our daughter's education. My son and daughter-in-law complained that they were the ones expected to take care of us in old age, but our money was all spent on our daughters. I went to court to announce that we had no expectation for their care in old age. But the court is powerless.

As shown in earlier studies (e.g. Xu, Reference Xu2001), rural families typically use extended family members or village cadres to intervene in family conflicts. Local courts rarely intervene in civil affairs unless a crime is involved. In the situation of Zhang's family, Grandma and Grandpa Zhang have not yet become physically dependent. They may not expect any help from their son; instead, their daughters have consistently expressed willingness to provide financial and physical care for their ageing parents. The increasing involvement in rural parents’ care by daughters was found in some research to be a ‘bonus’ in rural older parents’ retirement (Xu, Reference Xu2001: 311), or a broadened concept of filial piety in others (Luo and Zhan, Reference Luo and Zhan2012).

Descending transfer of child-care support

In rural Anhui Province, cultural expectations make paternal grandparent's care for their grandchildren a social norm. In patrilocal tradition, a daughter, once married, becomes a family member of the groom's family. Among the 50 families interviewed, 49 families had at least three living generations and, in 23 of these families, grandparents were caring for their grandchildren.

Mrs Tong, 67, and her husband, 70, have two sons and two daughters. Both sons have a separate household and one child, and the sons and their wives have migrated out of the village to work, leaving Mrs and Mr Tong to stay at home and raise their two grandchildren. The couple did not ask for any financial compensation from their adult children. In this way, they can help their children to earn more money without the burden of child care.

In the Liu family, the elderly grandparents were living with and caring for their two grandchildren, an 11-year-old granddaughter and 7-year-old grandson, when they were interviewed. Their son and daughter-in-law were both migrant workers living away from the village. Like the Tongs, the Liu grandparents did not ask their children to compensate them for child care. Instead, the grandparents paid for food, clothing and school-related costs for their grandchildren. Grandma Liu commented:

Last year, when the young couple decided to buy a flat in the city, the down-payment was 400,000 yuan. We helped them with 100,000 yuan in cash. We cannot let them own no space in a city when all other migrant workers are buying a flat. At home, we cannot let our grandchildren wear shabby clothing when they go to school. You see we have to help.

In rural families, when adult children find successful employment in a city, grandparents may move in to their children's urban homes to help raise their grandchildren, functioning as live-in maids. The Yangs, who have one son and one daughter, are grandparents to three grandchildren. Mrs Yang, 70, was expected to help raise her son's only child and move into the family's city home to do so. Mrs Yang left her rural home, where her husband still resides, to support her son's family. Mrs Yang reflected:

It has been six year since I came to the city. My husband is living alone in the village … I am sad for him – he does not cook well; he eats just to survive. We have to live apart in order for me to take care of our grandchild. I cannot wait until summer vacation comes because only during the summer and winter vacations can I have time to go home and visit my husband and be with him. I feel miserable living in the city. I don't like the lifestyle here.

Grandparents’ sacrifices to provide child care for their grandchildren are rarely compensated but often expected. These grandparents report rarely asking adult children to pay for the cost of living or schooling for grandchildren and, in conversation with their adult children, many adult children appeared to take the costs of this practice for granted. As with parents’ financial support, paternal grandparents are expected to care for their son's children while no care is expected from maternal grandparents. The intergenerational support from the older generation to the younger generation, according to the Chinese Confucian tradition of filial piety, should ensure an upward flow of care as older parents age. Yet, much of the descending support from older parents and grandparents remains unrecognised in these rural families. Has filial piety remained the norm in Lee Village?

Ageing and upward flow of support

In China, filial piety has long been the cultural practice of caring for ones ageing parents. Within this Confucian norm, adult children are expected to provide financial, physical and emotional care for their ageing parents (Zhan et al., Reference Zhan, Luo and Chen2012). In Lee Village, however, social and economic change, as well as rural-to-urban migration, have made the tradition of taking care of ageing parents much more difficult, if not impossible.

Mr Liu, at age 63, is taking care of his mother who is 86 years old. His mother had a fall a few months ago and requires active care. Even though Mother Liu has several children, all except Mr Liu are migrant workers or otherwise living outside Lee Village. Mr Liu's wife complains that he is not earning money while he cares for his mother; however, he believes that the care for his mother works well as he also cares for his own grandchild. Mr and Mrs Liu's children offered to pay their parents 1,000 yuan per year to help care for their grandson while Mr Liu's brother supplements this income by 100 yuan per month (or 1,200 yuan annually) as he cares for their elderly mother. When asked how he manages to live, he commented:

We live in a rural area, don't need to spend much. We harvest our own grain, extract our own cooking oil and plant our own vegetables. We only need the money to purchase some meat for nutritional purposes.

The care situation for widower Grandpa Li, 84, is less fortunate. Despite being barely able to see due to cataracts, he can still manage most activities of daily living. His oldest son built a small hut next to his house, where Grandpa Li lives. Here, his son brings him food daily. Grandpa Li reflects:

I'm old, can no longer work, only eat. Every day I wait for my son to bring me food, usually two meals a day. In the evenings, I usually do not eat. At sunset, I go to bed early. During the day, if there is sunshine, I would sit by the door to enjoy the sun or chat with neighbours. I cannot walk well, so I avoid going to places where there are too many people. If I get sick, I don't want to go to the hospital. I have lived long enough. I only fear that I would die by myself without anyone by my side. I hope I could die on Chinese New Year Festival because at that time, my children will be returning home. So, they can discover me in time to bury me. My sons have gone out to work, my daughter-in-law is taking care of the grandchildren.

As is the case with Mother Liu and Grandpa Li, many elders’ children have left Lee Village and migrated to urban areas with greater economic opportunity. Younger than the other two care recipients, Mrs Han, 67, has been left bed-ridden after having a stroke at age 60. Her husband is her full-time care-giver, despite having two sons and three daughters. She said:

I have been paralysed for seven years; my husband has been taking care of me. Our children are all busy. How can they possibly sustain such a long time of care? If it were not because of my husband who cooks, cleans and cares for me, I would have died long ago.

Sitting next to his wife on the edge of the bed, Mr Han smiled and said:

I have been used to the tasks of taking care of her. How can I possibly expect any of our children to take care of her?! They all have to work outside the village as migrant workers. Even if they come home, they can only stay around for a few days. It is impossible to expect their care for seven years. While I am capable of taking care of my wife, I will do my best. If I am dying, I will bring her along with me. If she dies first, I will make sure to have a proper funeral for her.

Married couples expressed having each other as a companion in old age as a blessing in many interviews. When widowed, and living alone, life can be rather depressing in rural China. In an unusual case within Lee Village, Mr Wang, a childless man at age 80, describes a rather different experience. He used to live with his niece, whom he had previously adopted. The two quarrelled often, so he decided to lease the land to his niece for 3,200 yuan per year and moved into a government-run elder-care home, paid for by the land-lease to his niece. Commenting on his current situation, he said:

Being a childless elderly man, the government takes care of me, they even buy me new clothing, I feel my life is much better here than living at home. The elder-care home even serves meat at times. When I am sick, they are responsible for treating my sickness. I actually feel pretty good. After I die, then, they can move my body home, or I don't know, and don't care. They can do whatever they want with my body.

The experience and outcomes following intergenerational conflict in Lee Village are not all like Mr Wang's. At the time of the study, Ms Zhang, a 75-year-old widow, had recently committed suicide. Ms Zhang had two sons and one daughter and, after her husband died, she moved in with her youngest son, who lives with mental illness. Ms Zhang's daughter-in-law was very unhappy in her marriage and, according to others in the village, often took out her frustrations on her mother-in-law; including insulting Ms Zhang several times in public. After an extended time living with her youngest son and daughter-in-law, Ms Zhang committed suicide by hanging herself.

Ms Zhang's suicide is not an uncommon phenomenon across China. The suicide rate among Chinese older adults has increased in the past 30 years, especially in rural China. An estimated 57,000 suicide cases were reported among older adults ages 55+ in 1990; this number increased to 74,400 in 2000 and 78,500 in 2001 (Huang and Liu, Reference Huang and Liu2013). Among these older adults, suicide rates are highest among those in rural areas; with rural elders being six times more likely to commit suicide than their urban counterparts in China (Huang and Liu, Reference Huang and Liu2013). Some of the top reasons cited for rural elders’ suicide included poverty, lack of health care and physical care, and lack of emotional support (Liu, Reference Liu2016); these issues are widespread in communities like Lee Village.

In the recent decades of rapid social change in China, large numbers of rural youth have migrated to urban areas in search of better employment and economic opportunity. From this change, an unprecedented rupture has emerged in the traditional Chinese practices of intergenerational exchange of support. Today's older generations have continued to fulfil traditional patrilocal and patrilinear expectations, providing financial support and child care to their adult children despite overwhelming costs to do so. As these elders approach the point of needing care and support from their children, many see little exchange in return, with limited expression of filial piety. Without substantial savings or a safety net beyond the fading hope of filial piety, drastic means, such as suicide, may be taken by many rural elderly parents.

Discussion

Intergenerational exchange is shown to be a normative pattern of social support between generations in most societies. Even though ageing parents in developed countries are more likely to provide descending flow of support to growing children, when parents are sick, an overwhelming percentage of children are known to make themselves available to take care of their parents – 65 per cent in the USA, 74 per cent in the United Kingdom, 70 per cent in Canada and 79 per cent in Germany (Rein and Salzman, Reference Rein and Salzman1995). In traditional China, intergenerational exchange has been facilitated through patriarchal traditions in which the senior male authority may hold the resources to ensure younger generations’ reciprocity. With drastic social and demographic changes accompanying rapid urbanisation, the traditional pattern of intergenerational exchange appears to face major challenges in China.

Cultural lag in intergenerational exchange

Findings in this study reveal that ageing parents in rural Anhui Province continue to live up to the traditional patrilocal and patrilinear expectations. They work hard, tilling the land or working as migrant labourers, in order to save enough money to secure homes for their sons’ families. This traditional intergenerational exchange pattern is similar in other rural Chinese provinces, such as Shandong (Zhang and Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2017) and Fujian (Lu, Reference Lu2015). Qualitative findings in this study further add to the support in the literature that patrilocal tradition in Anhui Province is still strong and prevalent. Alternative provisions of support and deviations from these traditions were met with criticism within Lee Village, such as when parents paid for their daughter's college education their sons threatened to revoke adherence to filial piety and refuse to care for their parents in their old age. Yan's (Reference Yan2016) recent study has shown that daughters are increasingly involved in ascending support for their natal family. Family dispute, even divorce, occurred when married daughters become more involved in natal families instead of patrilocal families. With the increasing power of women in the younger generation, future studies may continue to explore the changing dynamics of gendered cultural expectation: Do parents provide equal support to their sons’ and daughters’ families in urban and rural China? Do adult daughters and sons provide similar support for their ageing parents in urban and rural China?

Based on this qualitative study, the downward flow of support from parents to adult children outweighs the upward support provided by children to their parents. Several prior studies in China have labelled this pattern of intergenerational exchange as ‘exploitation’ (He, Reference He2009, Reference He2010, Reference He2011; Liu, Reference Liu2012; Lu, Reference Lu2015). We would point out that this intergenerational exchange must be considered within the research methods employed and the socio-historic context of China. Specifically, the emerging exchange imbalance could be explained in terms such as ‘deferred exchange’ and ‘cultural lag’.

To understand ‘deferred exchange’, we must recognise that most of the recent studies of rural intergenerational exchange patterns are based on cross-sectional studies. At any point in time, older parents who are helping adult children are likely to be still relatively young and independent, not yet at a point when ongoing aged-care is needed. The time for this generation's reciprocal return of support may be ‘deferred’ until they are in their late seventies or eighties. Cross-sectional data, whether qualitative or quantitative, should take caution in labelling the imbalance of intergenerational exchange as ‘exploitation’.

Yan's (Reference Yan2003, Reference Yan2011, Reference Yan2016) longitudinal qualitative studies appear to show a pattern of moving out and moving in between the generations. Many adult children have regained their appreciation of parents’ sacrifices, and re-assumed their filial responsibility, after they have become parents themselves. Adult children and ageing parents share the common goal of raising the third generation, together, gaining a ‘consensual solidarity’ between the generations. In the process, filial piety is redefined in a revised form to include better communication between the generations and reduced obedience of the younger generation in rural China.

Although the majority of China's rural families continue to abide by social contracts of intergenerational exchange, major social and demographic changes pose ongoing challenges to the maintenance of filial piety. The movement of adult children away from rural villages in search of better job opportunities and higher pay is facilitated by the process of urbanisation and the economic scarcity in rural regions. The fact that many, if not most, adult children are not living in the same household as their ageing parents nor fulfilling the traditional patterns of intergenerational exchange may not be a personal choice, but an unfortunate byproduct of the pressures of urbanisation. Regardless of this phenomenon being a personal choice or intention, the widespread presence of skipped-generation families has created a ‘cultural lag’ in rural China, in which the middle generation (i.e. adult children) is unable to fulfil their duty to care for older generations (i.e. elderly parents) in need. This burden and subsequent unfulfilled family support facing rural Chinese elders underlines the widespread need for social care, which points to a structural lag in rural China.

The structural lag of social care in rural China

The Confucian tradition of intergenerational exchange has functioned well in China for over 2,000 years. Yet, the rapid pace of industrialisation and urbanisation accompanied by population ageing is rapidly changing behaviour patterns in Chinese families. When large numbers (nearly 50%) of rural elders have no adult children in their household, who will be there to take care of these adults as they continue to age? As shown in earlier studies in China, increasing numbers of rural elders are committing suicide as a result of poverty, lack of health care and lack of emotional support. The altruistic tradition in the downward flow of intergenerational support works well when reciprocity is ensured by filial piety. When adult children are not nearby, simply providing financial support to parents may not be enough, as physical help is not easily purchased in rural China. While increasing numbers of assisted-living facilities and elder-care homes in urban China are taking care of the elders with or without children, government regulation continues to reinforce rural elders’ reliance on their children; only childless elders can receive welfare benefits for long-term care in rural China. As shown in this study, only one older adult met the criterion, and was living in a government-run elder-care home (yanglao yuan). Based on this study and several others in rural China, enhanced community or village-based social care is needed to fill the vacuum of support created by the emergence of skipped-generation families.

Is urbanisation and modernisation causing the decline of elders’ status in the family and society, and therefore the decline of cultural valuing of filial piety? Modernisation theories, dating back to Cowgill (Reference Cowgill1974), argued that as societies urbanise and modernise, older adults’ knowledge becomes obsolete. These retired elders are non-contributory and live in retirement homes and nursing homes that promote social segregation. Therefore, they have lost their social status at home and in the society. Yan (Reference Yan2003, Reference Yan2011) has argued for the rising ‘individualisation’ of Chinese families where the younger generation has an increasing amount of bargaining power for a more private, autonomous and individualistic lifestyle compared to a more family-oriented tradition. Even though the majority of adult children in Chinese families are continuing to provide and care for their ageing parents, when they fail to do so, as Xu (Reference Xu2001: 318) elaborated, there is no way to ‘compel them to perform the duty’. In major demographic and social changes of population ageing and urbanisation, familial care is no longer a panacea. When Chinese culture and social structures lag behind the pace of economic and demographic changes, the absence of alternative social insurance places millions of families, especially rural elderly family members, at risk. In Germany, France, the Netherlands and Sweden, national long-term care insurance for frail and physically dependent older adults have offered more flexible benefits by allowing cash benefits for home care services, including family members (Pavolini and Ranci, Reference Pavolini and Ranci2008). In the USA, consumer-directed care empowers elderly consumers to make care decisions and hire care-givers, including one's family members (Hooyman et al., Reference Hooyman, Mahoney and Sciegaj2016). Paying for families to care for ageing parents does not lead to the decline of family values; instead, studies have shown, it leads to higher quality of care because ageing parents have greater trust and confidence in their own family members while care-giving family members, usually women, are compensated financially, reducing care-giver stress and increasing satisfaction with care work (Simon-Rusinowitz et al., Reference Simon-Rusinowitz, Mahoney and Benjamin1998; Kunkel et al., Reference Kunkel, Applebaum and Nelson2003).

In China, the care work for young children and ageing parents are ‘silent reserves’ of the Chinese patriarchal system (Wang and Liu, Reference Wang and Liu2020). This care work is often ‘invisible,’ taken for granted as part of the Confucian tradition. Unsupported and unrecognised elder care needed in rural communities represents a denial of social rights to ageing and dependent citizens (Sansbury, Reference Sansbury1999; Cox, Reference Cox2015). While China has made big strides in implementing reforms in Social Security retirement systems in urban China, and providing universal non-contributory pensions for rural elders, a major structural change in long-term care is in urgent need in order to address the cultural and structural lagging due to population ageing and urbanisation.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (‘The Research of the Livelihood of Rural Migrant Workers and Their Sustainability’; grant/award number 17BSH137).