Party government in democratic polities will prevail when a party or parties win control of the executive as a result of competitive elections, when the political leaders in the polity are recruited by and through parties, when the (main) parties or alternatives in competition offer voters clear policy alternatives, when public policy is determined by the party or parties holding executive office, and when that executive is held accountable through parties. […] It is the contention of this paper that, with time, these conditions are becoming marked more by their absence than by their presence in contemporary European politics. In short, as a result of long‐term shifts in the character of elections, parties and party competition, it is precisely this set of conditions that is being undermined. (Mair, Reference Mair2008b, pp. 225–226)

Introduction

In representative democracies, governments' electoral platforms tend to be interpreted as a democratic mandate and should influence public policy (Budge & Hofferbert, Reference Budge and Hofferbert1990; Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge2003; Stokes, Reference Stokes2001). Issue attention is a topical dimension of mandate responsiveness: If this principle applies, the issues emphasized by governing parties in their manifestos should influence their policymaking priorities. How much room for manoeuvre is there, however, for political actors to shape policy on the basis of their election agendas?

Pioneering research has just recently begun to explore empirically how electoral priorities are reflected in policy outputs in single contexts (Brouard et al., Reference Brouard, Grossman, Guinaudeau, Persico and Froio2018; Borghetto & Belchior, Reference Borghetto and Belchior2020; Carammia et al., Reference Carammia, Borghetto and Bevan2018; Froio et al., Reference Froio, Bevan and Jennings2017), with mixed findings. This article moves the discussion beyond the descriptive question of the extent of manifestos' agenda‐setting effects in two respects. First, we develop a theoretical framework of policymaking capacity, which systematizes the institutional, operational and political conditions shaping mandate responsiveness. Constraints deriving from domestic political conflict (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1996) or from eroding executive popularity (Green & Jennings, Reference Green and Jennings2019) relate to liberal democratic limitations on executive power. Concerns have been expressed that other hurdles, linked to the emergence of multi‐level challenges, in particular regional integration (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1999), and to budget limitations (Ezrow et al., Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020) may erode representative democracy and prevent elections from fulfilling one of their core functions: providing a link between voters and public policy (Mair, Reference Mair2006). Empirical evidence for these effects is lacking: our second contribution is to provide a test for the constraining impact of institutional, operational and political hurdles. If confirmed, they may shed light on the variations observed in mandate responsiveness.

We opt for a within‐case comparison focused on Germany as a way to explore different dimensions of governing parties' capacity to set their campaign priorities on the legislative agenda, while holding the general context constant. Germany is both representative of typical parliamentary democracies and a fertile ground for testing our hypotheses, given considerable variance in all factors of interest. We create a dataset on electoral and legislative priorities across all policy sectors, merging data collected by the Comparative Agendas Project (CAP)Footnote 1 with national‐, issue‐ and party‐level data. These data include a unique set of substantive and control variables and cover a long period of time (1983–2016) with multiple alternations.

This article first discusses theories of party mandates and policy agendas and develops our argument on how different constraints may restrict mandates' relevance to legislative priorities. We then present our research design, complemented by a descriptive exploration of our data. Fixed‐effects Poisson regressions of the legislative agenda provide robust evidence for a strong correspondence between electoral and legislative priorities. This importantly complements research on pledges with regard to the prioritization of problems and to how far policies remain within the scope of mandates, corroborating that electoral commitments do matter and deserve more attention in public policy research. We also provide the first systematic empirical confirmation of the constraining effect of horizontal, vertical, operational and political constraints. The concluding section sums up our findings and discusses their broader implications for theories of comparative politics, democratic accountability and public policy.

Mandates and agenda‐setting

What agenda‐setting can tell about mandate responsiveness

Mandate responsiveness is one of the major premises of representative democracies. Empirical assessments usually look at pledge fulfillment (Naurin et al., Reference Naurin and Thomson2019a; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017). We adopt an alternative approach focused on issue attention, based on the expectation that governing parties' campaign issues shape policy agenda priorities significantly. Whether programme‐to‐policy linkages also hold with respect to policy priorities has seldom been addressed (Brouard et al., Reference Brouard, Grossman, Guinaudeau, Persico and Froio2018; Borghetto & Belchior, Reference Borghetto and Belchior2020; Froio et al., Reference Froio, Bevan and Jennings2017; Green‐Pedersen et al., Reference Green‐Pedersen, Mortensen and So2018; Grossman & Guinaudeau, Reference Grossman and Guinaudeau2021), despite several decades of public policy research pointing to agenda‐setting, that is the way governments prioritize the innumerable problems demanding public intervention, as a decisive stage in policymaking and a source of bias in the representation of social groups (Jones & Baumgartner, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005; Schattschneider, Reference Schattschneider1960).Footnote 2 Mandate responsiveness is at its best if campaign promises and enacted policy coincide in terms of both priorities and substance. Pledge and agenda‐setting research are complementary in at least three respects.

First, the agenda‐setting approach allows us to circumvent the one‐sidedness of pledge research that ‘only looks at the question of whether pledges are enacted – not whether what is enacted is pledged’ (Louwerse, Reference Louwerse2012, p. 1252). Mandates allow voters to ‘authorize’ their representatives to pass a set of policies on their behalf (Louwerse, Reference Louwerse2012). Implicitly, they also delineate a legitimate perimeter for government action, as such an authorization is not given for topics without any explicit pledges (Roberts, Reference Roberts2010; Stokes, Reference Stokes2001). The relevance of pledge fulfillment therefore depends on a significant correspondence in priorities. Conversely, a correspondence in priorities only would at least mean that representation works well with respect to Schattschneider's ‘conflict of conflicts’. Assessing the policy relevance of electoral programmes requires us to work in the opposite direction to pledge fulfillment research, that is approaching public policy as a whole and analysing how far it reflects programmes.

Second, our focus on attention is consistent with salience theory, according to which political parties compete not only by shifting their positions but also by pushing their preferred issues onto the agenda (Budge, Reference Budge2015).

Third, policy priorities have distinct, but equally important functions as substantive positions. Curtin et al. (2010, p. 930) observe that the fragmentation of electorates makes it increasingly difficult for parties to aggregate sets of policies fostering wide support and therefore to act as authorized agents when in office: ‘The result is the promotion of a party policy in election programs that is often less a mandate for action and more a symbolic signaling of priorities and core concerns.’ The formulation of pledges mostly leaves room for interpretation – and their implementation in practice results in the agenda‐setting of a proposal that is then negotiated and adjusted. If pledged and implemented policy often differ in substance, agenda‐setting seems all the more topical. By making electoral pledges, candidates commit to set certain issues on the agenda and voters expect them to follow through by passing policy. Citizens may find it easier to judge whether some action was taken or not on campaign priorities than to assess whether policy corresponds to what was promised at elections. Research on valence (e.g. Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Sanders, Stewart and Whiteley2009), issue ownership (Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996) and salience linkages (Bernardi, Reference Bernardi2020; Green & Jennings, Reference Green and Jennings2019; Reher, Reference Reher2014, Reference Reher2015; Traber et al., Reference Traber, Hänni, Giger and Breunig2022) underlines the importance of parties' agenda responsiveness for citizens' political attitudes and voting behaviour.

The mandate responsiveness hypothesis

Mandate responsiveness would imply that public policy priorities mirror those emphasized by the governing parties in their campaigns. Significant incentives derive from the anticipation of electoral sanctions for inaction on their campaign priorities or for unauthorized policy reforms (Matthiess, Reference Matthiess2020; Naurin et al., Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019b; Werner, Reference Werner2019). Electoral platforms attract considerable attention, with journalists drawing up tables of the main campaign announcements or referring to such pledges as an important benchmark for assessing a government's record (Håkansson & Naurin, Reference Håkansson and Naurin2016, pp. 395–396). The topics parties emphasize in their programmes and in their policy decisions may also be similar because both are shaped by the same factors, related in particular to public priorities or to parties' constitutive issues, such as immigration for far‐right parties (Green & Jennings, Reference Green and Jennings2019). Routine partisan activities, including press releases or parliamentary questions, are increasingly analysed as a medium of party competition (Borghetto & Russo, Reference Borghetto and Russo2018; Louwerse, Reference Louwerse2012; Sagarzazu & Klüver, Reference Sagarzazu and Klüver2017). The same may be true for public policy: When legislating, elected officials have incentives to stick to their campaign priorities. They may then benefit from their preferred topics topping the policy agenda (Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996).

These arguments lead us to expect governing parties to use their formal powers and political resources to pass legislation on their mandate priorities. This should result in a match between the policy priorities entailed in governing parties' programmes and legislative outputs.

H1: Mandate responsiveness hypothesis. Stronger issue emphasis in governing parties' electoral programmes increases the likelihood of legislation on this issue.

Constraints and the need for a conditional approach

Despite the strong theoretical arguments and core normative implications of mandate responsiveness, scholars often assume its impact on agenda‐setting and public policy to be marginal at best and focus instead on the necessity for governments to respond to problems (Adler & Wilkerson, Reference Adler and Wilkerson2013; Stokes, Reference Stokes2001), short‐term public concerns (Bevan & Jennings, Reference Bevan and Jennings2014; Green & Jennings, Reference Green and Jennings2019; Stimson et al., Reference Stimson, MacKuen and Erikson1995) and media discourses (Van Aelst & Walgrave, Reference Van Aelst, Walgrave and Zahariadis2016; Vliegenthart et al., Reference Vliegenthart, Walgrave, Baumgartner, Bevan, Breunig, Brouard, Bonafont, Grossman, Jennings, Mortensen, Palau, Sciarini and Tresch2016). Yet, the extent to which representatives balance those imperatives with mandate responsiveness should be measured empirically rather than postulated. Scholars have only recently begun to examine the agenda‐setting effect of mandates, with mixed conclusions: A study on Italy finds a significant impact of electoral priorities on legislation (Carammia et al., Reference Carammia, Borghetto and Bevan2018) while Brouard et al. (Reference Brouard, Grossman, Guinaudeau, Persico and Froio2018) find only conditional effects in France, and Froio et al. (Reference Froio, Bevan and Jennings2017) show no robust effect. A deeper understanding of the conditions under which democratic mandates shape policy agendas is therefore needed, in particular in more typical parliamentary settings.

This seems all the more relevant as influential scholars from other backgrounds – from political economy to comparative politics and European studies – have voiced concerns about governments' leeway to shape policy agendas according to their mandate against a background of growing constraints (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1996; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1999; Mair, Reference Mair2006). In this view, developments towards more complex patterns of contingencies and dependencies upon external actors risk undermining the linkages between voters and policy setting, the fundament of representative democracy. These concerns call for a systematic reflection on governing parties' capacity to deliver on their mandate, paving the way for an empirical account of constraints. Such a reflection helps move the emerging literature on mandates' agenda‐setting effects forward by drawing attention to the conditions shaping the capacity of governments to respond to their mandate. Once adequately modelled, these conditions may then shed light on variations in mandate responsiveness and help to assess the room available for key democratic linkages.

Modelling capacity to respond to mandates

A multi‐dimensional concept

Debates on the room for mandate responsiveness raise the question of governments' policymaking capacity, that is their ability to focus on their preferred issues and enforce policy change (Green & Jennings, Reference Green and Jennings2019). The most intuitive approach to capacity focuses on its institutional dimension, related to governments' formal powers and what Lijphart (Reference Lijphart1999) approaches as the horizontal executive‐parties dimension. In this view, governments' capacity is moderated by institutional hurdles to policymaking, reflecting in particular the degree of electoral disproportionality, the effective number of parties, the resulting necessity to build coalitions and the number of veto players (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1996; Tsebelis, Reference Tsebelis2002). The aforementioned debates suggest that institutional capacity needs to be considered beyond this horizontal power division in order to account for vertical processes of power delegation, in particular to supranational institutions. Government capacity may then vary depending on multi‐level dynamics (Peters & Pierre, Reference Peters and Pierre2001). Importantly, capacity does not only depend on institutional power allocation but also entails an operational dimension related to the resources ensuring the practical feasibility of a policy (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Ramesh and Howlett2015) and a political dimension shaped by governments' vulnerability towards public pressure (Bernardi, Reference Bernardi2020; Green & Jennings, Reference Green and Jennings2019). This multidimensional approach integrating (horizontal and vertical) institutional, operational and political dimensions allows us to learn from comparative politics, political economy and public policy research for a better understanding of mandate responsiveness. While horizontal institutional capacity alone sheds light on variations across systems, our multidimensional concept accounts better for variations across time and policy sectors. The following paragraphs examine each dimension in turn and derive testable hypotheses for each of them.

Horizontal institutional capacity and constraints linked to domestic political conflict

Existing conditional approaches to programme‐to‐policy linkages tend to focus on institutional capacity. They look at the domestic hurdles in terms of democratic checks and balances (Schmidt 1996) and observe higher rates of pledge fulfillment in majoritarian (e.g. Royed, Reference Royed1996) than in consensual political systems (Thomson, Reference Thomson2001). Counter‐majoritarian institutions, such as the second chamber in a bicameral political system, may increase friction and complicate government action on mandate priorities (Bevan & Jennings, Reference Bevan and Jennings2014). Deviations from the mandate may also result from the need to compromise with coalition partners, especially if their programmes differ widely (Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2011). Such challenges may have grown in the context of increasingly heterogeneous coalitions in many countries (Mair, Reference Mair2008b). Two forms of conflict are potentially constraining, deriving, respectively, from diverging positions (at the core of spatial models of party competition in the Downsian tradition) or priorities (modelled in salience theory). Political parties may then explicitly refrain from acting in the most contentious domains or establish ex ante and ex post control mechanisms to limit ministerial drifts from coalition compromises (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Bäck and Hellström2021). This makes it more difficult to legislate on the issues of concern. Green‐Pedersen et al. (Reference Green‐Pedersen, Mortensen and So2018) corroborate the idea that coalition disagreement reduces the agenda‐setting power of the prime minister's party (see also Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017). Other studies did not find such a conditioning impact on mandate responsiveness (Brouard et al., Reference Brouard, Grossman, Guinaudeau, Persico and Froio2018; Schermann & Ennser‐Jedenastik, Reference Schermann and Ennser‐Jedenastik2014).

Based on these arguments, we generally conjecture that the correspondence between mandate and legislative priorities increases with the number of pivots controlled by government parties and with greater cohesion within government coalitions. This leads us to the following hypotheses:

H2a: Institutional constraint hypothesisMandate priorities are more strongly reflected in legislative outputs when the government parties control the second chamber.

H2b: Coalition conflict hypothesisMandate priorities tend to be less well reflected in legislative outputs when the ideological distance between coalition partners is greater.

H2c: Coalition priority divergence hypothesisMandate priorities tend to be less well reflected in legislative outputs when the priorities of the coalition partners are more dissimilar.

Vertical capacity and constraints linked to Europeanization

Democratic concerns in a context in which dispersion of decision‐making away from central states restricts elected governments' margins for manoeuvre invite us to broaden institutional capacity so as to account for multi‐level dynamics, in particular in the context of regional integration (Mair, Reference Mair2006, Reference Mair, Graziano and Vink2008a; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1999). Peter Mair prominently argued that the delegation of national competences to European institutions restricts the range of instruments available to governing parties and the space for domestic electoral competition. Their policy repertoire is also limited by the elimination of numerous practices interfering with the realization of the common market (Mair, Reference Mair, Graziano and Vink2008a; see Nanou & Dorussen, Reference Nanou and Dorussen2013, for empirical insights on the restriction of party positions). In this context, governments need to respond not only to their mandate but also to principals located in part beyond the domestic realm (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1999).

Empirical evidence as to the effective impact on mandate responsiveness is scarce and models usually focus on domestic constraints.Footnote 3 EU‐level influence on national lawmaking is empirically more limited than commonly thought (Brouard et al., Reference Brouard, Costa and König2011). Scholarship has not yet examined effects on mandate responsiveness beyond single sectors (but see Knill et al., Reference Knill, Debus and Heichel2010, on the partisan imprint on environmental policy in countries with different levels of supranational integration). We therefore explore hurdles related to the reallocation of authority away from central states through the lens of EU‐related constraints, starting from the hypothesis that they hinder mandate responsiveness. Constraints could yet be more modest than expected, as governing parties themselves exert an influence on EU policies through their representation in key EU institutions. In addition, constraints will bite differently depending on the extent of integration and (mis‐)fit between domestic status quo and EU norms (Börzel & Risse, Reference Börzel, Risse, Featherstone and Radaelli2003).

H3: EU constraints hypothesisMandate priorities tend to be less well reflected in legislative outputs when the national government shares more competences with the EU in the respective policy area.

Operational capacity and budget constraints

Capacity does not derive only from formal constitutional powers but has also an operational dimension: Mandate responsiveness relies on the availability of sufficient (material, human, technical) resources for the enactment of the policies promised at elections (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Ramesh and Howlett2015). This involves, in particular, a cost factor which may be marginal under favourable economic conditions associated with budget surpluses, but prohibitory in times of economic hardship. Budget constraints may be particularly strong today, following decades of economic slowdown and neoliberal reforms in Western economies (Streeck, Reference Streeck2014). Most governments seek a balanced state budget, especially in Eurozone countries, which have committed to keep their public deficits below 3 per cent – a norm that has been reinforced over recent years in the context of several bailouts provided by EU institutions (Alonso & Ruiz‐Rufino, Reference Alonso and Ruiz‐Rufino2020; Conti et al., Reference Conti, Hutter and Nanou2018). Economic hardship and budget deficits may also generate overwhelming problems that distract governments away from their programme (Borghetto & Russo, Reference Borghetto and Russo2018; Borghetto & Belchior, Reference Borghetto and Belchior2020). While budget constraints on the relationship between electoral and legislative priorities have not yet been measured, several findings indirectly point to their potential relevance. The political economy literature suggests that budget spending reflects macroeconomic conditions rather than the partisan composition of government (Huber & Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2001). Moreover, if responsiveness to public opinion is conditional on favourable macroeconomic conditions (Ezrow et al., Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020), this is also likely to be the case for mandate responsiveness. The positive impact of economic prosperity has already been documented in studies of pledge fulfillment (Praprotnik, Reference Praprotnik2017; Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017). We therefore hypothesize that budget constraints dampen the agenda‐setting of mandate priorities.

H4: Budget constraints hypothesisMandate priorities tend to be more strongly reflected in legislative outputs when public finances improve.

Political capacity and public pressure

Last but not least, governments' capacity to pass policy depends on their ability to gain support from sufficiently broad coalitions of societal, public and private actors (Lindvall 2017). Past studies suggest that executive approval plays an important role: popular representatives enjoy wider latitude and will be less prone to retreat from their policy preferences (Karol 2009). In contrast, a decline in popularity may nourish resistance to policy change, generating hurdles on decision‐making and incentives to respond to the concerns prioritized by the public rather than following through on a partisan agenda (Bernardi, Reference Bernardi2020; Green & Jennings, Reference Green and Jennings2019; Hobolt & Klemmensen, Reference Hobolt and Klemmensen2007).

H5: Popularity hypothesisGovernment popularity strengthens the relationship between mandate and legislative priorities.

Constraints and their anticipation

Political parties are likely to pay attention to constraints of all types when drafting their electoral programme. Especially in countries where coalitions are inevitable, or where European integration and budget orthodoxy foster a widely shared consensus, future government parties have to anticipate the related hurdles as best as they can. In this sense, constraints may have consequences not only on mandate responsiveness but also on the scope and level of ambition of mandates. Both effects may be relevant to voters, but in different ways: while the first may result in disappointment about a mismatch between campaign priorities and public policy, the second could translate into a restriction in political alternatives. Given our approach, the present article sheds light only on the first effect, something we will return to when interpreting our findings. This focus is consistent with mandate theory, which is about the nexus between pledged and enacted policy.

Constraints are not always easy to evaluate in advance (Stokes, Reference Stokes2001). More generally, parties running for an election do not only need to remain credible but also to embody attractive visions. To this end, government parties are often tempted to promise action also with respect to areas of high constraints and high incentives. The findings presented below do not point to significant anticipation effects: the coefficients in Table 1 show that our estimates of mandate responsiveness remain stable when controlling for a range of constraints.

Case selection and empirical strategy

This study measures the reflection of German governing parties' mandate priorities in public policy, and how several capacity conditions constrain this relationship. This requires data on issue attention in both governing parties' manifestos and policymaking, measured on the same scale. We use data collected by the German CAP team on issue emphasis in party manifestos and enacted laws.Footnote 4 We use fixed‐effects Poisson regression models to model the monthly number of laws enacted on a given topic and analyse how the government's electoral priorities (percentage of manifestos on a given topic) translate into legislative attention (monthly number of laws adopted on the same topic). The data are available over a period of three decades (1983–2016) and make it possible to use interaction terms to analyse how the relationship between manifesto and legislative priorities varies depending on all conditions of interest.

A within‐system comparison allows to deal with the noise induced by national confounding factors. We focus on Germany and take advantage of the various institutional, political and economic configurations observed over time, as well as of differences in the extent of Europeanization across policy issues. The strength of German counter‐majoritarian institutions, the need to form coalition governments and corporatism make Germany a relatively unlikely case for observing an effect of electoral priorities on the legislative agenda. Consequently, analysing how legislative priorities in Germany reflect electoral issues can provide a lower bound for parties' ability to act on the topics emphasized in their campaigns. Germany is moreover a good case to investigate the conditions affecting programme‐to‐policy linkages considering the variation of our variables of interest over time. There were regular alternations in the party composition of government with varying internal ideological ranges, and as we will see, under changing conditions in terms of economic context and government popularity. Europeanization of policymaking varies considerably across both time and policy areas. Majority control in the upper chamber (Bundesrat) also changed at several points in time.

Dependent variable: The legislative agenda

Our dependent variable is based on manual coding of the thematic profile of each law adopted by the German parliament (N = 4060) between 1983 and 2016, using the CAP coding scheme for 19 issue topics (Breunig & Schnatterer, Reference Breunig and Schnatterer2020; Breunig et al., Reference Breunig, Guinaudeau and Schnatterer2021).Footnote 5 Each law is assigned to a single topic category, which makes it possible to count the number of laws adopted each month on each issue. The variable therefore captures the number of laws adopted on topic i during each month t.Footnote 6 Our data consist of a panel cross‐section with 19 topics observed for 374 months, which adds up to 7106 observations (19 issues * 374 months).

Independent variable: Priorities in governing parties' platforms

Our main independent variable, which is based on content analysis of governing parties' manifestos, captures the proportion of sentences devoted to each issue in each manifesto.Footnote 7 Party manifestos are a core source for research on the issue content of party competition. They are most relevant for our specific research question, as an authoritative document produced by parties as unitary actors, in contrast to individual politicians' claims or parties' routine press releases, whose binding character may be disputed.

German governments consistently comprised of two parties over the period of study.Footnote 8 For each administration, each coalition partner's manifesto was coded by assigning each sentence to a CAP issue category. These data were then used to measure the attention devoted to each topic (percentage of manifesto). For each government, starting from the premise that coalitions involve making policy compromises (Green‐Pedersen et al., Reference Green‐Pedersen, Mortensen and So2018), we aggregated these percentages with a weight reflecting the number of parliamentary seats (Döring & Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2020) of each coalition partner.Footnote 9

Moderating variables

We test our conditional hypotheses by modelling interactions between attention in electoral platforms and a list of factors reflecting our hypotheses. We investigate four types of constraints.

First, three variables relate to horizontal institutional capacity. A dummy variable captures whether the government is supported by a majority in the Bundesrat – the German upper chamber representing the Länder. This variable takes the value of 1 when the cabinet enjoys an absolute majority in the Bundesrat and 0 otherwise. Governments consistently controlled the Bundesrat until the early 1990s, but this is no longer the case, which was abundantly commented on in public discourses as an obstacle to policymaking.Footnote 10 The two other variables relate to policy differences between coalition partners. Partners may diverge from each other in substantive terms. They can also disagree as to the priority for action. Accordingly, we compute two measures of intra‐government distance, measured for each issue and government: (1) the absolute left‐right distance, measured from Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP) data for each cabinet (Volkens et al., Reference Volkens, Bara, Budge, McDonald and Klingemann2013), and (2) the absolute difference in the proportion (per cent) of attention devoted by both partners to each specific topic.

Second, we measure the vertical allocation of power between national and EU institutions with the percentage of adopted laws on each topic that was directly influenced by the EU (Beyer, 2018). Following the advice from representatives of the parliamentary documentation research service, we considered only pieces of legislation explicitly implementing European law as directly influenced by the EU.

Third, we use the annual government budget balance (in the percentage of GDP as provided by the World Bank) to operationalize budget constraints.

Finally, we measure political capacity through the lens of aggregate assessments of government popularity, as polled monthly by the Politbarometer. Footnote 11

Controls

Attention to a topic in the government platform does not mean that this topic will constantly be the subject of new laws. Our models thus control for cumulative law production, that is the number of laws adopted on the topic in the previous months of the legislative term (Brouard et al. 2018).

We also control for the ideological composition of the government to avoid biases related to the heterogeneity of what is promised and to the fact that some policies, for example liberal economic reforms, do not require as many budget resources as social policy. This is done using a categorical variable characterizing left‐wing (SPD–Green), right‐wing (CDU–FDP) and grand coalitions (CDU–SPD).

Previous studies focusing on other countries have observed variations in mandate implementation over the course of the electoral cycle (Brouard et al., Reference Brouard, Grossman, Guinaudeau, Persico and Froio2018; Borghetto & Belchior, Reference Borghetto and Belchior2020; Duval & Pétry, Reference Duval and Pétry2019), which may in part reflect governments' stronger policymaking capacity in the honeymoon period. We therefore add a control variable capturing the sequence of the electoral cycle (with a distinction between the first 12 months, the last 12 months and ‐periods of routine in between). We use a 6‐month lag corresponding to the average duration of the German legislative process. Finally, we control for time with a count of the number of months expired since our initial period.

Model

We structure our data as a pooled time series with topics as the cross‐sectional unit varying over months. The dependent variable is the number of laws adopted within a topic in a given month. Modelling the data at this level allows us to control for volatile factors such as economic conditions, government popularity or electoral cycles. Yet, this strategy might raise concerns that this artificially inflates the sample size and may lead us to underestimate the standard errors (Garritzmann & Seng, Reference Garritzmann and Seng2016), or to inflate the number of zeros, as for most topics and months, no law is adopted. Thirty‐three per cent of the observation of the dependent variable is actually greater than 0. Replications of the main model at the level of cabinets or with a zero‐inflated model, available in online Appendices 3 and 4, provide comforting evidence that our findings are robust also to these alternative specifications.

Poisson and negative binomial regression are best suited to model count data (Hausman et al., Reference Hausman, Hall and Griliches1984). The latter option at first sight has the advantage of modelling dispersion as an additional parameter, thereby addressing the concern that overdispersion in our data (

![]() $\bar{n_{nlaws}} = 0.56$ and

$\bar{n_{nlaws}} = 0.56$ and

![]() $var(n_{laws}) = 1.30$) could lead to underestimate standard errors (Hilbe, Reference Hilbe2011: 208). However, the structure of our data, with observations within topics and months that are not independent, requires fixed effects to be included in the model to account for case and time‐invariant heterogeneity.Footnote 12 When used in combination with fixed effects, Poisson models have been shown to outperform negative binomial models: while the latter can lead to inconsistent estimates due to incidental parameters (Allison & Waterman, Reference Allison and Waterman2002), panel fixed‐effect Poisson models estimate consistent parameters no matter how the dependent variable is distributed (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge1999). Importantly, it allows for both over‐ and under‐dispersion and when clustering standard errors, it is also robust to any type of serial correlation potentially affecting the dependent variable (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge1999, p. 95). We therefore opted for fixed‐effect panel Poisson regression with robust standard errors. The main equation of our models, specifying each constitutive term, is presented in online Appendix 2. Footnote 13

$var(n_{laws}) = 1.30$) could lead to underestimate standard errors (Hilbe, Reference Hilbe2011: 208). However, the structure of our data, with observations within topics and months that are not independent, requires fixed effects to be included in the model to account for case and time‐invariant heterogeneity.Footnote 12 When used in combination with fixed effects, Poisson models have been shown to outperform negative binomial models: while the latter can lead to inconsistent estimates due to incidental parameters (Allison & Waterman, Reference Allison and Waterman2002), panel fixed‐effect Poisson models estimate consistent parameters no matter how the dependent variable is distributed (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge1999). Importantly, it allows for both over‐ and under‐dispersion and when clustering standard errors, it is also robust to any type of serial correlation potentially affecting the dependent variable (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge1999, p. 95). We therefore opted for fixed‐effect panel Poisson regression with robust standard errors. The main equation of our models, specifying each constitutive term, is presented in online Appendix 2. Footnote 13

Findings

Mandates' impact on legislative priorities

We begin with an assessment of the mandate responsiveness hypothesis (H1). Figure 1 presents the data on issue attention in governing parties' manifestos and in legislation, aggregated at the term level. This allows for a first examination of how the number of laws evolves compared to the level of attention (per cent) in platforms.

Figure 1. Issue attention in German governing parties' manifestos and adopted legislation (1983–2016).

Issues receive variable levels of attention, resulting in gaps between low‐ and high‐profile subjects. However, the overall amount of attention tends to be congruent across both agendas, with only a few noticeable exceptions characterized by disproportionate attention in the electoral (education, labour) or in the legislative (infrastructure, government operations) arenas. Patterns vary across issues, but common fluctuations are discernible on most issues. This preliminary evidence calls for multivariate analyses to assess the robustness of this relationship when controlling for relevant factors.

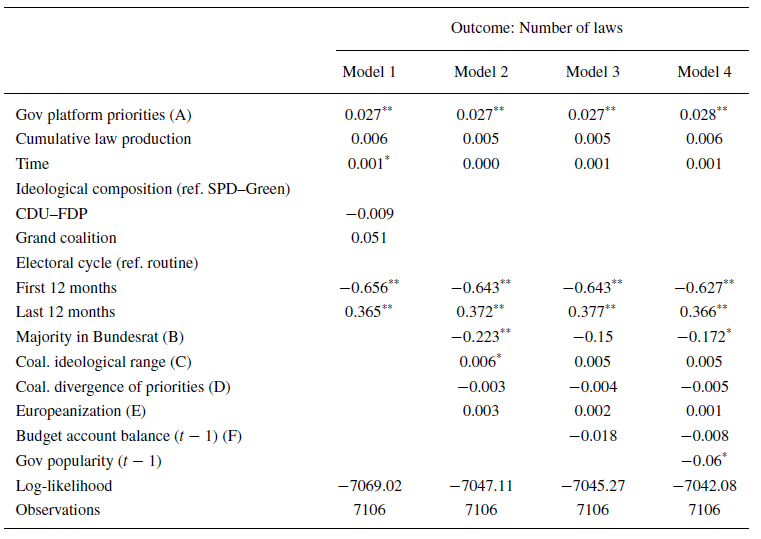

Table 1. Main models

Note: We use fixed‐effect Poisson regressions to model the monthly number of laws on each topic. An increase in manifesto salience is significantly associated with an increase in the number of laws, even when controlling for the number of laws already adopted and a range of likely confounders.

* p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

The three models in Table 1 display the main results of fixed‐effects Poisson regressions testing our expectation that legislative priorities reflect issue attention in the ruling parties' platforms. The coefficients indicate for each month how the probability of an additional law on a certain topic varies for a one‐unit change in the predictors. For the main variable of interest, this would be for an increase of attention to this issue in the governing parties' platforms by 1 per cent. In a step‐by‐step approach, we add basic control variables (Model 1), variables on institutional capacity (Model 2), the variable on operational (budget) capacity (Model 3), and finally those on political constraints (Model 4).

The coefficient for government platform priorities is consistently significant. It is not sensitive to the inclusion of control variables. The other coefficients suggest that legislative productivity tends to reach higher levels for grand coalitions and, to some extent, over time (this effect vanishes when controlling for institutional capacity). In line with business cycle theories, more laws are passed in the run‐up to elections, less in the first months of a term. Legislative productivity is higher when the government does not control a stable majority in the Bundesrat, confirming König (Reference König1999) observation that opposition from the second chamber does not dampen legislative productivity. While popular governments adopt fewer laws, neither coalition divergences (be it in terms of positions or of priorities) nor the extent of EU competences or budget conditions seem to significantly influence the number of adopted laws. Mandates thus come out of our analyses as a predominant determinant of legislative priorities. This does not mean that our control variables do not play a role as a moderator, a question we will turn to in the section A hollowing‐out of mandate representation?.

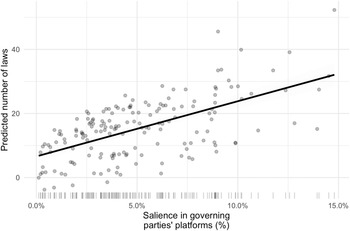

The evidence of a powerful relationship between governing parties' platforms and laws is strong. In substantive terms, this means that a 1 per cent increase in manifesto salience tends to increase the expected number of laws on a given topic and in a given month by 2.8 per cent.Footnote 14 This is a substantial effect, considering that it is estimated at the level of single months and that the amplitude of variations in issue attention in electoral platforms is considerable.Footnote 15 This becomes even clearer when looking at the predicted number of laws depending on issue salience in the platform in Figure 2, which shows that a 5 per cent increase in electoral attention translates into approximately seven additional laws on a given topic for a 4‐year mandate. This finding is strong and robust to alternative specifications of the model, the dependent and independent variables (see online Appendices 3–8). Overall, our analyses clearly demonstrate that party manifestos matter for the legislative agenda. This may come as a surprise, given the relative marginality of parties and elections in the literature on public policy and particularly in studies of policy agenda setting. The strong effect is also striking, given our focus on a political system involving numerous powerful veto players.

Figure 2. Predicted number of laws adopted during a mandate period, conditional on platform salience.

Notes: This figure represents the predicted number of laws for each topic and each month, according to Model 4. The expected number of laws increases with manifesto salience. The ticks along the x‐axis indicate the overall distribution of issue salience in manifestos, which rarely overcomes 10 per cent.

A qualitative look at each government's most important policy decisions corroborates our statistical findings: A vast majority of them were announced in the governing parties' platforms and taken up in the coalition agreement. A systematic review would exceed the scope of this study, but a prominent example is the climate package adopted in 2019 by the current grand coalition, in line with the SPD commitment to develop a climate protection law. For the Merkel III government (2013–2017), also a grand coalition, this includes the first‐time introduction of a federal minimum wage, perhaps the most salient electoral topic at the 2013 election, but also the reform of the stay‐at‐home mothers' pension (Mütterrente). Other reforms include the possibility for children born to foreign parents in Germany to opt for dual citizenship, the adoption of a legal quota of 30 per cent for women in supervisory boards, laws on the gender pay‐gap, same‐sex marriage and rent controls (Mietpreisbremse). Counter‐examples of policies enacted in the absence of a mandate are rare and mostly justified by governments with respect to unexpected or focusing events. This applies to Angela Merkel's decision to confirm the phasing‐out of nuclear energy, as decided by the previous red‐green cabinet following the Fukushima disaster (Thurner, Reference Thurner, Müller and Thurner2017), as well as to temporarily open German borders to refugees without any border checks in 2015 in the midst of the European migrant crisis (Mushaben, Reference Mushaben2017). In the absence of such justification, unauthorized reforms face strong opposition. For example, the German adoption of a law introducing a car toll (Pkw‐Maut) in 2015 was contested with regard to Angela Merkel's previous explicit campaign statement that there would not be any car toll while she was Chancellor.

A hollowing‐out of mandate representation?

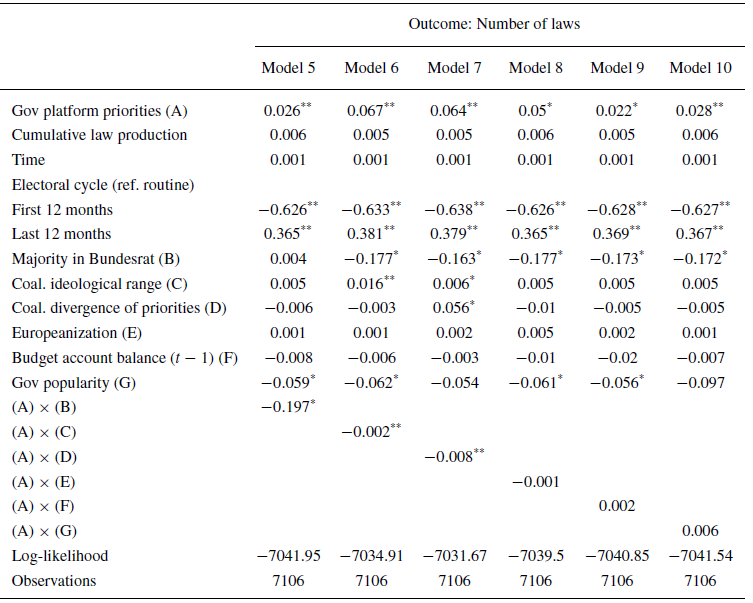

To test our conditional hypotheses, we model interactions between electoral priorities and each of the conditions. We first investigate horizontal institutional capacity. The models in Table 2 and marginal effects in Figure 3 explore the constraining impact of the absence of a stable majority supporting government legislation in the Bundesrat (H2a), the dissimilarity of the ideological positions (H2b) and issue attention (H2c) of coalition partners.

Table 2. Conditional models

Notes: Models presented in this table expand Model 4. Each of them features an interaction term between manifesto salience and one of the moderating variables. The main effect of manifesto salience remains significant. Besides for the majority in the upper chamber, the marginal effects displayed in Figures 3–5 suggest that this main effect varies according to the degree of conflict within the government, the level of Europeanization, economic conditions and government popularity.

* p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Figure 3. Marginal effect of electoral priorities on legislative attention, for increasing levels of coalition disagreement over positions and priorities.

Notes: Figures are based on Models 6 and 7, respectively. The vertical bars represent 95 per cent confidence intervals. The ticks along the x‐axis indicate the distribution of each of the moderating variables. The y‐axis denotes the marginal effect of a variation by 1 per cent in issue salience in governing parties' platforms on the probability of an additional law on this topic in a given month. Positive values indicate that higher manifesto salience leads to more laws, whereas negative values indicate the reverse relationship. The effect of manifesto salience decreases the more coalition partners diverge from each other, in terms of left‐right positioning as well as priorities.

The constitutive term for platform priorities in Model 5 does not corroborate our intuition that the absence of a majority backing the governing coalition in the Bundesrat opens opportunities for opposition parties to oppose legislation on electoral issues (H4a). In this configuration, electoral priorities still exert a significant effect. The interaction term is not significant, suggesting that Bundesrat control does not significantly affect mandate responsiveness.

In contrast, our analyses support the expectation that coalition politics are key to the policy relevance of the mandate. Consistent with H2b and H2c, differences between the coalition parties generate hurdles. Dissimilarities in terms of positions and priorities both appear to strongly restrict lawmaking on mandate priorities. However, ideological conflict needs to be very strong to cancel out the influence of electoral priorities (a difference of at least 28 per cent on the CMP left‐right scale, which was reached only by one government over the period of study, the Merkel I 2005–2009 government, or about 7 per cent in the share of attentionFootnote 16). These striking results support our expectation of constraints linked to intra‐coalition disagreement.

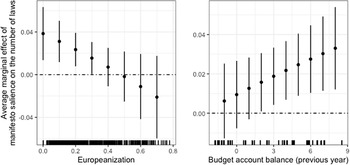

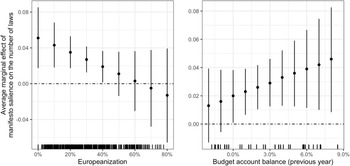

We now test the conditional effect of the vertical and operational capacities, as formulated in Hypotheses 3 and 4. The marginal effects represented in Figure 4 corroborate both hypotheses with a negative interaction term for Europeanization and a positive one for budget account balance. The constitutive term for platform priorities in Model 7 shows that their relationship with legislative subjects is significant for areas immune to any Europeanization, for example those for which none of the adopted legislation originates at EU level, in particular social policy and – until the signing of the Maastricht Treaty – areas such as education, labour or security policies. In line with Mair's argument, the marginal effect of electoral priorities on laws decreases with Europeanization. This effect is no longer significant for policy areas with more than 40 per cent of laws directly influenced by EU legislation. These include areas of considerable public salience, such as the internal market and agriculture over the whole period and – since the founding treaties of the 1990s – energy, transport and the environment.

Figure 4. Marginal effect of electoral priorities on legislative attention, for increasing levels of Europeanization and account balance.

Notes: Figures are based on Models 8 and 9, respectively, and should be read as the previous figures. The ticks along the x‐axis indicate the distribution of the variables on Europeanization and budget balance, respectively. As expected, the relationship between manifesto and legislative salience decreases in policy areas dominated by the European Union and increases the more positive the budget balance.

Figure 5. Marginal effect of electoral priorities on legislative attention, for increasing levels of government popularity.

Notes: The figure is based on Model 10 and should be read as the previous figures. The ticks along the x‐axis indicate the distribution of the variables on government popularity. In line with hypothesis H5, legislative salience reflects mandate priorities only from a certain level of government popularity.

Our findings also confirm the conditioning impact of budget conditions. The constitutive term for platform priorities shows that for a positive budget balance their impact on legislation is significant. The marginal effects displayed in Figure 4 show this is no longer the case when the account balance gets negative, however, as in the period from the early 1990s to the early 2000s.

This first empirical account of how mandate responsiveness is constrained by vertical and operational capacity generally supports the concerns that the relationship between electoral and legislative priorities relies on a certain level of national sovereignty and favourable budget conditions. When these conditions are not met, electoral and legislative priorities appear to be statistically disconnected from each other.

Conclusion: capacity and the agenda‐setting impact of manifestos

Elections are meant to provide a key link between voters and public policy in democracies. This link may be undermined by a disconnection between electoral mandates and government policy. Such concerns have gained momentum in the political science literature, as well as in many political discourses in view of a range of constraints that are believed to ‘hollow‐out’ representative democracy. And indeed, while pledges are fulfilled at high rates across liberal democracies, findings as to the agenda‐setting impact of mandates on policy taken as a whole remain rare and at best mixed. This raises the question of the conditions shaping governing parties' capacity to deliver on the policies for which they receive a mandate. We depart from the intuition that once appropriately conceptualized and operationalized, variations in capacity may shed important light on contrasted observations as to elections' policy relevance.

Our contribution is twofold. First, we have developed a multidimensional concept of capacity complementing classic institutional power division at the national level with vertical aspects of power delegation as well as operational and political capacity. Second, we have tested its main implications with a focus on salient conditions related to each dimension of capacity. This allows the integration of topical debates about the declining room for manoeuvre in the context of European integration, budget austerity and public pressure into the study of mandate responsiveness. We draw on data collected by the CAP project and on a within‐system comparison centered on Germany permitting the noise to be limited and different institutional, political and economic configurations to be compared over time, as well as differences in the extent of Europeanization across issues and periods. Germany is a fruitful case for analysis, as a political system representative of the widespread kind of parliamentary settings with proportional representation and a multiparty system as well as because of considerable variance in all variables of interest.

This first comprehensive examination of the most prominent factors commonly expected to impede mandate responsiveness confirms their constraining impact in most cases and strengthens the arguments according to which representative democracy is under stress. While German debates on policymaking capacity have focused on hurdles in the Bundesrat, resulting in the 2006 federalism reform, most constraints empirically derive from intra‐coalition disagreement, Europeanization, scarce budget resources and public pressure instead. Further comparative exploration of the implications of bicameralism is needed, especially in more symmetric forms such as in Italy. These findings reveal that horizontal institutional capacity matters to the agenda‐setting impact of mandates in a way that is similar to what has been observed on pledge fulfillment, but that vertical, operational and political capacity are also at play. There is no obvious reason why the related constraints would not apply to other contexts with coalitions, European integration and budget austerity, and these factors therefore seem highly relevant to future research on programme‐to‐policy linkages.

Having acknowledged the role of constraints, it is important to emphasize two aspects. First, vertical and operational constraints may limit the room available for political competition and representative democracy, yet restrictions on mandate responsiveness due to public pressure rather reflect how mandate and anticipatory representation combine, in line with democratic normative models (e.g. Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge2003). Second, under most circumstances, these constraints moderate mandates' imprint on policy rather than offsetting it entirely. Democracy is not yet ‘hollowed‐out,’ and electoral platforms overall remain an important predictor of legislative priorities. We can show that an increase of 5 per cent in issue attention in governing parties' platforms is associated with an average of seven additional laws over the term. Substantively, this effect goes far beyond those usually found when investigating the determinants of policy change. This finding still holds under alternative model specifications and when controlling for an encompassing set of factors shaping legislative productivity and mandate implementation. In a political system with multiple counter‐powers, this provides strong evidence for the crucial relevance of mandates to policymaking. Governing parties have incentives to act in the areas announced in their campaign and appear to be able to put these issues on the agenda. This may be even more the case in political systems with a stronger concentration of power, as well as in systems with a pure proportional electoral system giving even more weight to political parties. Elections and programmes therefore matter and provide accurate signals of the issues to be anticipated on the legislative agenda over the years to come.

These findings have important implications for future studies. Given their strong and robust impact, government platforms should be relevant, as a determinant of legislative attention, for a wide range of analyses ranging from public policy to democratic representation. The conditional analyses suggest that this is especially the case in domains governed mainly at the national level and subject to limited intra‐coalition conflict. In other areas, we have shown that mandate responsiveness is under (sometimes considerable) pressure in the context of coalition constraints, Europeanization and economic hardship. In this sense, our findings are both good and bad news for mandate responsiveness. Overall, mandates do matter, but their impact is moderated under several circumstances, which inform efforts to improve the quality of representation. Proposals intended to foster political competition and mandate responsiveness at the European level (such as the Spitzenkandidaten procedure) might be one way to enhance the relevance of elections in multi‐level systems. Our results also highlight the strategic importance of preserving budget leeway in times of growing fiscal competition and limited growth. They underline the relevance of the growing body of research on coalition bargaining and coalition governance as major determinants of mandate responsiveness, especially when the rise of challenger parties results in ideologically heterogeneous coalitions.

This article sets the basis for an intriguing research agenda on the conditions shaping the policy relevance of elections. On the one hand, we have acknowledged that it cannot be excluded that constraints of various types exert additional impact on the scope and ambitions of manifestos, an aspect that we leave to further research. On the other hand, comparative research is needed to assess how far variations in capacity account for the varying policy relevance of mandates and to identify the institutional features that are most favourable to the policy relevance of elections. While we have focused on particularly salient conditions to explore the respective weight of the three components of capacity, each of them may be approached through the lens of further factors which deserve close attention as well: the constraining impact of constitutional courts or portfolio control as to horizontal capacity, of decentralization and federalism with regard to vertical capacity or, concerning operational capacity, of the varying level of technicity of policy issues. Comparing issues is warranted to detect how far certain types of constraints affect some areas more than others, and parties, for example to take into account the extent of fit (or misfit) between single parties and EU policy. The relationships between different types of constraints, which may be conceptualized as convertible resources that could compensate for each other, also call for specific investigations. Finally, future research should focus on how mandate responsiveness pays off electorally and builds democratic support. While voters are known to sanction pledge breakage (Matthiess, Reference Matthiess2020; Naurin et al., Reference Naurin, Soroka and Markwat2019b; Werner, Reference Werner2019), little is known as to their response to the more general consistency between policies as a whole and authorizing mandate.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to a fellowship of the Humboldt Foundation, Isabelle Guinaudeau benefited from ideal working conditions at the University of Stuttgart. We would like to address our warmest thanks to Christian Breunig for giving us access to the German CAP data as well as for excellent comments. We also benefited from Michael Herrman's very helpful advice as to our modelling strategy. We are grateful for further feedback and comments received from André Bächtiger, Patrick Bernhagen, Elisa Deiss‐Helbig, Angelika Vetter, as well as from the participants of the panel on ‘Political Parties: Strategies and Outcomes’ at the online ECPR General Conference in 2020. Last but not least, this project importantly benefited from our exchange with Emiliano Grossman with whom we have been working in parallel on related matters.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data Availability Statement

Replication materials are available at https://github.com/benjaminguinaudeau/replication_mandate_responsiveness

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table 1: Descriptive statistics for numeric variables

Table 2: Descriptive statistics of numeric variables for each policy issue

Table 3: Alternative model specifications

Table 4: Term‐level models

Table 5: Alternative Specifications

Table 6: Alternative operationalization of salience

Table 7: Models with first‐differences

Figure 1: Distribution of First differences of Government Popularity

Figure 2: Marginal effect of electoral priorities on legislative attention, for increasing changes in government popularity

Table 8: Removing laws influenced by the EU