Introduction

Conventional perspectives on law‐making in parliamentary democracies assume a fairly limited role of legislatures in formulating policy. Given the fusion between government and parliamentary majority, drafting laws is largely done in government offices, and the resulting proposals are expected to be rubber‐stamped by members of the governing majority. Scholars have increasingly questioned this account of legislating in parliamentary systems. A growing body of work has provided evidence that parliamentary actors extensively rework government proposals and that parliamentary amendments do shape government policy.

Previous research has suggested two distinct motivations. In their seminal work on European multiparty governments, Martin and Vanberg (Reference Martin and Vanberg2004, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005) have described legislative institutions as guarding the coalition compromise. Policy‐motivated members of the majority amend government proposals to prevent deviations from the coalition compromise. More recently, Fortunato (Reference Fortunato2019) has argued that vote‐motivated members of the governing majority use amendments to signal differences from their coalition partners to mitigate electoral losses due to blurred party brands as a consequence of common coalition policies.

Despite growing awareness of the status of parliaments in the legislative process, the existing research has provided an incomplete picture. The dominant perspectives on legislative review have focused on intra‐coalition dynamics while disregarding why the opposition engages with government proposals. Multiple studies have shown that opposition parties propose extensive amendments to coalition policy (Russell & Gover, Reference Russell and Gover2017; Thompson, Reference Thompson2015; Shephard and Cairney, Reference Shephard and Cairney2005; Loxbo and Sjölin, Reference Loxbo and Sjölin2017; Andeweg et al., Reference Andeweg, De Winter and Müller2008). Neither policy nor vote motivations can easily explain this behaviour. Given their minority status, amendment proposals by the opposition are typically rejected in parliament (Thompson, Reference Thompson2015; Loxbo & Sjölin, Reference Loxbo and Sjölin2017; Andeweg et al., Reference Andeweg, De Winter and Müller2008; Behrens et al., Reference Behrens, Nyhuis and Gschwend2023), ruling out a policy motivation. Moreover, not only do opposition parties not suffer a diluted policy profile through cooperation in a coalition government, opposition amendments are almost invisible to the public. They typically do not get picked up by the media, and they are less salient than coalition amendments. This casts doubt on a vote motivation for opposition amendments, leaving us with the question: Why do opposition parties draft amendments to government policy at all?

This analysis aims to contribute to this question by studying the motivations for opposition engagement with government bills. We argue that an office‐seeking motivation best explains why members of the opposition review government legislation. Amendments are assumed to follow an intra‐party logic where legislators propose amendments to signal ambition and competence to their party peers. Party leaders rely on these signals and promote active legislators to higher office. We test these assumptions using a new dataset of amendments to over 400 government bills from a German state parliament. Our findings support the hypotheses that (i) ambitious members of the opposition are more active in legislative review and that (ii) opposition parties reward legislators' efforts by promoting them to higher office.

The results have important implications for our understanding of opposition efforts in legislative review, as well as for how parties decide upon promotions in parliamentary democracies. Our analysis contrasts with existing research on legislative review by explicitly focusing on opposition amendments and by proposing an office motivation rather than a policy or vote motivation. We also speak to research on individual legislative activities and their effects on political careers (Bailer et al., Reference Bailer, Meissner, Ohmura and Selb2013; Bailer et al., Reference Bailer, Breunig, Giger and Wüst2022), which has largely focused on bill sponsorships. As bill initiation is a party‐level activity in most parliamentary democracies, legislators cannot rely on this instrument to signal expertise and ambition for higher office. We add to this research, as it is not obvious how the motivations for legislative speech or bill initiation translate to less visible legislative efforts. Moreover, we provide the first joint test of the links between ambition and legislative behaviour and between legislative behaviour and career trajectories, which have only been tested separately in existing research.

Legislative review, opposition parties and political careers

Parliamentary scrutiny of government legislation

The legislative process in parliamentary systems is government‐centric. As governments can typically rely on a parliamentary majority, policy is shaped in government offices. Once a piece of legislation is introduced into parliament, members of the majority have little incentive to block the proposal and risk bringing down the government, while the minority lacks the numbers to push for relevant changes.

Given the importance of executives for the substance of policy, research on legislating in parliamentary systems has traditionally focused on the factors shaping policy choices before a piece of legislation is formally proposed. One feature of parliamentary systems that has elicited particular interest is how coalition governance impacts policy decisions. Scholars have intensely studied the problem of ministerial autonomy (Laver and Shepsle, Reference Laver and Shepsle1996) and how delegating authority to ministers comes at the price of potential agency loss.

Researchers have identified a number of strategies that coalitions adopt to bind ministers to the coalition compromise, such as appointing junior ministers (Müller and Strøm, Reference Müller, Strøm, Müller and Strøm2001; Thies, Reference Thies2001). Along similar lines, committee chairs can be assigned to serve as watchdogs over coalition policy (Kim and Loewenberg, Reference Kim and Loewenberg2005; Carroll and Cox, Reference Carroll and Cox2012). In addition to institutional roles for reducing delegation problems in coalition governments, research has highlighted the important function that parliaments play in keeping tabs on coalition partners. Moving beyond the somewhat stylized account of legislating in parliamentary systems, there is an increasing awareness of the amount of redrafting that happens after legislation is introduced into parliament. Amending legislation allows members of the governing majority to rein in policy deviations from overly entrepreneurial ministers (Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2004, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005). A somewhat different perspective on amendments is provided by Fortunato (Reference Fortunato2019) who suggests that amendments enable coalition partners to maintain distinct policy profiles, as they suffer from blurred profiles in a government coalition.

Despite increasing attention to how frequently and extensively parliaments redraft legislation in parliamentary systems, there are notable gaps in the research. First and foremost, as opposition parties are largely unsuccessful in shaping legislation, their efforts have typically been disregarded in existing research. In a rare exception, Fortunato et al. (Reference Fortunato, Martin and Vanberg2019) show how opposition parties can improve their standing in legislative review by relying on their agenda‐setting powers in opposition‐chaired committees. The authors find that bill proposals assigned to opposition‐lead committees are subject to more changes than bills assigned to committees chaired by coalition members. This type of opposition influence does not come about through the adoption of opposition amendments, however, but through the elevated position of opposition chairs in committee deliberations.

Hence, the fact that most amendment proposals by the opposition are doomed to fail begs the question what prompts these efforts in the first place. While opposition review of government bills is extensive across Europe (Andeweg et al., Reference Andeweg, De Winter and Müller2008; Loxbo & Sjölin, Reference Loxbo and Sjölin2017; Russell & Gover, Reference Russell and Gover2017), the high numbers of amendments stand in sharp contrast to their low success rates, as opposition amendments are almost always voted down. This pattern is most pronounced in majoritarian systems where power is often concentrated in the hands of a single party. In their study of the United Kingdom, Russell and Gover (Reference Russell and Gover2017) observe a success rate of about 7 per cent for opposition amendments. Thompson (Reference Thompson2015) estimates even smaller figures for the history of British law, with about 0.6 per cent of opposition amendments being successful. Similar conclusions are reached for the Scottish parliament (Shephard & Cairney, Reference Shephard and Cairney2005) and the Swedish Riksdag (Loxbo & Sjölin, Reference Loxbo and Sjölin2017). Low success rates are even observed for the Dutch Tweede Kamer, which is often cited as the prototype of a consensual democracy where law‐making is assumed to cut across government–opposition lines (Andeweg et al., Reference Andeweg, De Winter and Müller2008).

Why do opposition members of parliament (MPs) propose amendments that are doomed to fail? While opposition MPs have a variety of legislative tools at their disposal, amendments are distinct from many other legislative tools. For instance, some legislative instruments are useful for increasing the visibility of parties or legislators. The most obvious examples are plenary speeches (Louwerse and van Vonno, Reference Louwerse and van Vonno2021), and, to a lesser extent, parliamentary questions. Green‐Pedersen (Reference Green‐Pedersen2010) has argued that the increasing importance of parties' ‘issue competition’ has prompted more parliamentary questions, as parties compete by drawing attention to issues that are beneficial to them. Parliamentary questions constitute an ideal instrument for such issue competition, as they are often featured in the media and the government has to respond to the issues raised by the opposition. Legislative activities can also be grouped by the extent to which they are subject to party discipline and controlled by the party leadership. For example, in some parliamentary systems, MPs are expected to attend plenary sessions, as parties try to avoid public condemnation for shirking. Consequently, it is more straightforward to explain such activities than legislative amendments.

Amendment proposals by members of the opposition have a distinct character. Amendments can be expected to be less tightly controlled by the party leadership, especially among the opposition ranks. For members of the governing majority, amendments are a high‐stakes affair as they can upset the delicate balance between coalition partners. Amendments are less consequential for the opposition, as no coalition agreements have to be considered when scrutinizing government policy. Several other characteristics set amendment proposals apart from other parliamentary activities. First, as legislation is technically complex, drafting amendments to government bills is a time‐consuming endeavour that requires considerable cost and policy expertise. Paying attention to the nuances of the proposed legislation is especially crucial since amendments – in contrast to speeches – entail formal objectives that leave no room for manoeuvre, and can thus be characterized as credible commitments rather than cheap talk. Second, one can expect amendments to go largely unnoticed by the public. In a comparative study of 18 European parliaments, Mattson and Strøm (Reference Mattson, Strøm and Döring1995) find that in all but four legislatures, committee meetings are closed to the public. Moreover, due to their technical and procedural nature, amendments are rarely picked up by the media.

Against this backdrop, it is doubtful whether dominant perspectives on legislative review provide a satisfactory explanation for the detailed work of opposition members on government legislation. Given their dismal success rates, it is unlikely that a policy motivation holds much water for opposition amendments. A vote motivation is not more plausible either. The argument that parties rely on amendment proposals to signal policy differences from competitors is closely tied to coalition dynamics (Fortunato, Reference Fortunato2019), where the clarity of party profiles suffers from joint policy proposals. These considerations are absent for opposition parties. What is more, the low levels of publicity make amendments poor instruments for policy signalling to begin with – especially for opposition parties, whose proposals are generally rejected and are therefore unlikely to shape policy.

There are possible party‐level explanations which can shed light on opposition scrutiny of government bills and which are that is unrelated to the success of amendments. First, as efficiency is thought to be a priority for government legislation, amendments can be a tool for causing legislative delay (Dion, Reference Dion1997; Henning, Reference Henning and Döring1995). Second, when opposition proposals are rejected in parliament, some amendments to highly visible bills force coalition parties to give public, and at times difficult, explanations for why opposition proposals are turned down.

There are several reasons why it is unlikely that opposition amendments are commonly motivated by obstruction – in parliamentary democracies in general and in our empirical case in particular. First, the possibility of causing legislative delay varies by institutional setting, and the necessary conditions are often absent in Western European democracies. As Henning (Reference Henning and Döring1995) notes, ‘the higher the agenda control of the government, the lower c.p. the ability of any non‐governmental agent to delay the final adoption of a bill’ (p. 604). In the majority of Western democracies, either the government or the majority in the lower house sets the committee agendas (see Döring (Reference Döring and Döring1995)). In other cases, such as the Landtag, committees determine their own agendas, but their composition mirrors the composition of the lower house. Such institutional settings limit the ability of the opposition to use legislative amendments for delaying government legislation. The argument that opposition amendments to key bills force governments to reject popular demands is reasonable but fails to answer ancillary questions such as who among the opposition ranks makes the effort to showcase the coalition parties' non‐cooperation or why bills with similar levels of salience are characterized by different levels of opposition scrutiny.

As we will argue below, amendment proposals by the opposition are best explained by an office motivation. In making this argument, we highlight a second and more subtle gap in the existing literature. Whereas previous research has mostly taken a party‐level perspective on legislative amendments, little attention has been paid to the question, which legislators spearhead these efforts. On the one hand, we thus provide an explanation for the large number of unsuccessful opposition amendments. On the other hand, we go beyond party‐level dynamics and explain who among the opposition ranks is shaping party interactions in parliament.

Political ambition and individual legislative efforts

As policy and vote motivations are unlikely to provide a satisfactory explanation for why opposition legislators rework government legislation, an office motivation constitutes a more plausible alternative. From this perspective, opposition legislators neither attempt to shape government policy nor do they try to sell the public on their parliamentary achievements. Instead, legislators invest time and effort to draft doomed amendments to underline their aspirations for higher office and to demonstrate their skills to the party leadership, such that when the time comes to govern, they have proven to be able to work on legislation in earnest as a minister or committee chair.

Framing amendments as intra‐party signals ties into a broader research on political ambition and its effects on political behaviour. Researchers have consistently found that legislators differ in their career goals and that these goals are reflected in their political behaviour. Going back to Schlesinger (Reference Schlesinger1966), scholars have typically employed a threefold typology for classifying political ambition, where legislators can either aim to retire from public office (discrete ambition), to be re‐elected to their current position (static ambition) or to attain higher office (progressive ambition) (Schlesinger, Reference Schlesinger1966, p. 10; Black, Reference Black1972). In terms of vertical career advancement, progressive ambition implies that legislators aim to move from lower‐level to higher‐level assemblies. In terms of horizontal career advancement, progressive ambition implies that legislators aim to be promoted to a more prestigious office at the same level, such as a committee chair, or a ministerial appointment.

There is consistent evidence for the impact of legislators' ambition on a variety of parliamentary behaviours, such as bill initiation and sponsorship (Chasquetti and Micozzi, Reference Chasquetti and Micozzi2014; Micozzi, Reference Micozzi2014b, Reference Micozzi2014a), roll‐call voting (Hibbing, Reference Hibbing1986; Meserve et al., Reference Meserve, Pemstein and Bernhard2009) and plenary speeches (Hoyland et al., Reference Hoyland, Hobolt and Hix2019). As these studies have mostly focused on the legislator‐centric political systems in the Americas, the dominant perspective on the link between political ambition and legislative behaviour has been one of personal vote‐seeking. An intra‐party signal of political ambition is more easily reconciled with legislative behaviour in party‐centric political systems, where legislators' career trajectories are at the mercy of the party leadership (Kaiser and Fischer, Reference Kaiser and Fischer2009).

Two arguments can help substantiate this claim. First, existing research on (progressive) ambition and legislative behaviour has focused on vertical career advancement, where personal vote‐seeking is a reasonable electoral strategy. Existing research has largely disregarded horizontal political ambition, where legislators may be interested in being promoted to a more prestigious office at the same level. In these cases, the support of the party leadership is crucial and intra‐party signals of ambition and ability are key (Dockendorff, Reference Dockendorff2019). But even when legislators are interested in vertical career advancement, signalling their skill to the party leadership is vital under common electoral rules in parliamentary systems. Whether it is the prevalence of list systems or the absence of primary contests – if legislators cannot convince their party that they possess the skills to perform their parliamentary duties, the party leadership will likely turn a deaf ear to their bid for career advancement.

Second, while signals to the party leadership are generally more important for legislators in parliamentary democracies than in less party‐centric systems, intra‐party signals are particularly likely when considering comparatively low‐key activities such as legislative amendments. In general, legislators can rely on a whole range of tools to signal expertise through their legislative activities, such as bill initiation, parliamentary questions, speeches, or amendments. Whereas bills or speeches constitute visible signals to the electorate (e.g., Däubler et al., Reference Däubler, Bräuninger and Brunner2016), amendments are fairly technical matters that are often introduced at the committee stage and are therefore mostly invisible to the electorate. Moreover, no other instrument permits legislators to show their ability to draft legislation and underline aspirations for higher office, as private member bills are often heavily regulated by the party leadership in parliamentary systems. Hence, legislators cannot consistently use them to signal their expertise and ambition. Additionally, both frontbenchers and backbenchers need to signal expertise to their colleagues. While party leaders have already achieved prestigious positions in their current assembly (horizontal promotion), advancing one's political career across parliaments (vertical promotion) requires building and maintaining a reputation for legislative skill. These characteristics make amendments suitable for signalling to other legislators who pay closer attention to the parliamentary proceedings than the general public, irrespective of the MP's current position. In sum, we expect members of the opposition to employ amendments to signal skill and ambition to their party leadership, which leads us to the following hypothesis:

H1: Ambitious members of opposition parties propose more amendments to government legislation than non‐ambitious members.

One empirical upshot of the argument that legislators use amendments to signal their ambition and ability to the party leadership is that proposing amendments has an effect on career trajectories. Rational and especially ambitious political actors can be expected to pay close attention to which behaviours are ultimately successful in advancing the careers of their peers and which strategies they should pursue to advance their own. If ambitious legislators notice that investing time and effort in the legislative process is not rewarded by the party leadership, they should be expected to spend their precious time elsewhere.

While there is ample evidence for the effect of political ambition on a wide variety of legislative behaviours, fewer studies have systematically investigated how such behaviour feeds into the subsequent careers of active legislators (e.g. Louwerse and van Vonno, Reference Louwerse and van Vonno2021; Dockendorff, Reference Dockendorff2019; Yildirim et al., Reference Yildirim, Kocapinar and Ecevit2019). To the best of our knowledge, no study has integrated both perspectives to study how political ambition shapes legislative behaviour and how legislative behaviour, in turn, impacts the career trajectories of ambitious legislators. In trying to fill this gap, we combine both facets of political ambition. Assuming that ambitious members of the opposition behave rationally, they should only try to signal their ambition to the party leadership through legislative amendments if parties pick up on legislators' efforts, thus increasing the odds that they are being promoted to higher office down the line, which leads us to the second hypothesis:

H2: Members of the opposition who propose more amendments are more likely to be promoted to higher office in the next legislative term.

Opposition legislative review

Case selection

An empirical test of our arguments requires an analysis of individual legislator efforts in legislative review. Most importantly, we need data from a case: (i) that allows measuring progressive, static and discrete political ambition; (ii) where tracking individual efforts in legislative review is possible; and (iii) that is representative of parliamentary democracies. To this end, we draw on data from the Landtag Baden‐Württemberg, a full‐time parliament across three legislative periods (2006–2011, 2011–2016, 2016–2021).

There are several advantages of studying the Landtag. While the concept of political ambition easily travels across legislatures, as even politicians in national legislatures can strive for career advancement within their assemblies, a state‐level parliament provides us with an excellent opportunity to measure political ambition as the potential for advancement is higher in state‐level parliaments. As state‐level politicians can strive for a national or a European career, we are likely to observe progressive ambition among MPs who hope for horizontal or vertical career advancement.

Three factors make our case particularly suitable. First, the Landtag Baden‐Württemberg is one of the largest state‐level legislatures in Germany, with comparatively high levels of professionalization and legislative capacity (Appeldorn and Fortunato, Reference Appeldorn and Fortunato2022). This allows us to take advantage of its state‐level nature for measuring political ambition, while simultaneously studying a full‐time professionalized parliament with similar proceedings as national legislatures. Second, the Landtag is subject to high fluctuations in governing coalitions in the time frame of the analysis, making horizontal promotions available to a wide range of MPs. In the three legislative terms, there were three different coalition governments between CDU and FDP (2006–2011), Greens and SPD (2011–2016) as well as between Greens and CDU (2016–2021). Except for the right‐wing AfD, which entered the parliament for the first time in 2016, all parties have served in government and opposition at least once since 2006. Therefore, in addition to vertical career trajectories, there is considerable potential for horizontal career mobility. Third, the Landtag provides fine‐grained data on MPs' behaviour. In other parliaments, amendments are often signed by numerous legislators or even the entire party group, making it difficult to attribute amendments to specific MPs in order to measure their individual efforts. In the Landtag, only a few MPs work on amendments, with most proposals being signed by less than four legislators (mean = 3.67). Hence the possibility of constructing measures of political ambition as well as individual amendments sets our case apart from other legislatures. In the Online Appendix, we systematically compare the Landtag to the other German state‐level parliaments and national Western European assemblies. While there is considerable variation in the design of legislative institutions, our case is similar to most other European legislatures in terms of the committee design and rewriting authority which is crucial for the study of legislative review.

Bill scrutiny in the Landtag Baden‐Württemberg

As is common in European legislatures, most bills are initiated by government, while legislative review is common. Amendment proposals can be submitted at two stages during the legislative process. First, committee members have the right to rewrite bills. They can submit their amendments before or during the first committee hearing when the proposals are voted on by committee members. Second, after the revised committee version of the bill is circulated by the committee chair, the new bill version is voted on during the second plenary reading. At this stage, all members can propose amendments. Amendment proposals are usually drafted by a few authors which are individually named on the amendment proposals.

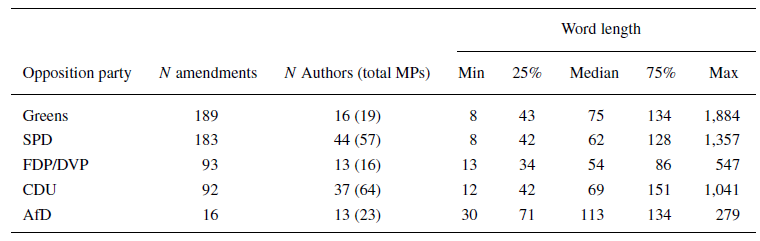

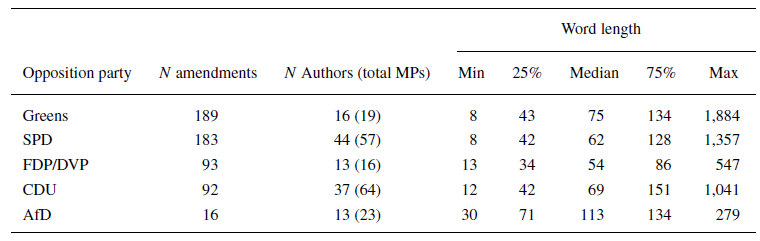

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for all opposition amendments to government legislation in our study frame. The figures show that submitting amendment proposals is common for all party groups with two opposition parties having submitted over 90 (FDP/DVP, CDU) and two other groups over 180 (Greens, SPD) amendments. Less activity is observed for the right‐wing populist AfD, as the party has only been represented in parliament since 2016. Table 1 further documents that amending legislation is not an isolated phenomenon by a few legislators, such as party leaders, who set the party agenda. Third, opposition proposals can be of considerable length, with the most extensive drafts covering several pages.

Table 1. Bill scrutiny by opposition parties in the Landtag Baden‐Württemberg

421 cabinet bills were introduced in the time frame of the analysis. The table presents descriptive statistics on the number of amendments, the number of distinct authors out of all party group members and the distribution of amendment word length. Data is included for all party groups in opposition.

Empirical strategy

Data and dependent variables

To construct the dataset for the empirical analysis, we collected all bills and the related amendment proposals from the official records of the Landtag. Since the procedural rules for budget and constitutional bills differ from those for ordinary legislation, they were excluded, resulting in 421 pieces of government legislation. Testing our hypotheses on the link between political ambition and legislative review (Hypothesis 1) and the effect of MPs' legislative behaviour on subsequent promotions (Hypothesis 2) requires constructing two datasets with two different units of observation.

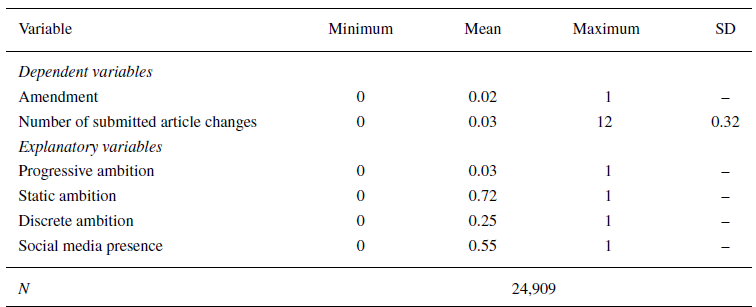

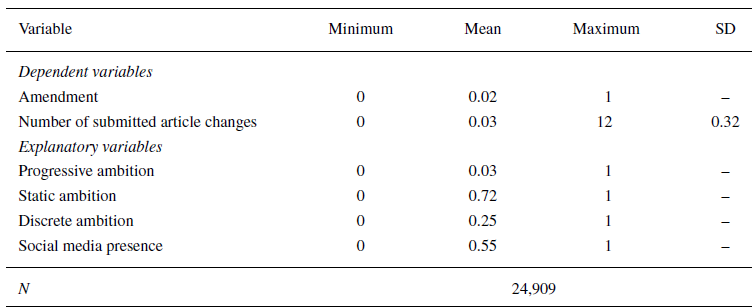

To test Hypothesis 1, the first dataset is constructed at the bill× MP level by merging bill‐level data with information from the 196 opposition MPs in the three legislative periods, resulting in a dataset of

![]() $n=24,909$. We include two measures of legislative activity as dependent variables. First, for each proposal and MP, we include a binary indicator whether an MP has submitted an amendment to a draft bill at any point in the process.Footnote 1 Second, we quantify MPs' engagement as the number of article changes an MP submitted to a bill.

$n=24,909$. We include two measures of legislative activity as dependent variables. First, for each proposal and MP, we include a binary indicator whether an MP has submitted an amendment to a draft bill at any point in the process.Footnote 1 Second, we quantify MPs' engagement as the number of article changes an MP submitted to a bill.

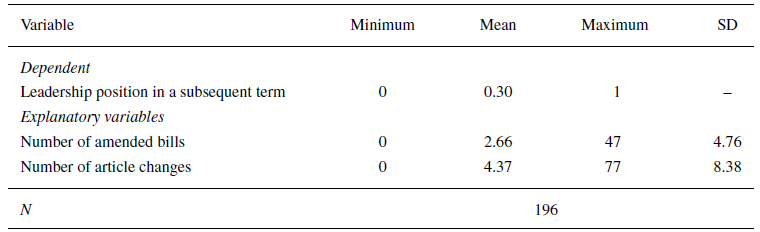

Regarding the second hypothesis, we trace MPs' parliamentary careers after a legislative term has finished. This second dataset is constructed at the term× MP level. There are

![]() $n=196$ observations for this analysis. This dataset contains a binary dependent variable, which documents whether an MP (i) moved into a leadership position in the next legislative term or (ii) to an upper‐level legislature. Leadership positions include standing committee chairs, parliamentary chairs and party group managers, house speakers as well as ministers and junior ministers. As upper‐level legislatures, we include promotions to the Bundestag and to the European Parliament. MPs who did not get appointed to any of these positions or left the legislature are coded as zero. Table A3 in the Online Appendix provides descriptive statistics on MPs' political careers. Tables 2 and 3 present descriptive statistics for key variables in both datasets.

$n=196$ observations for this analysis. This dataset contains a binary dependent variable, which documents whether an MP (i) moved into a leadership position in the next legislative term or (ii) to an upper‐level legislature. Leadership positions include standing committee chairs, parliamentary chairs and party group managers, house speakers as well as ministers and junior ministers. As upper‐level legislatures, we include promotions to the Bundestag and to the European Parliament. MPs who did not get appointed to any of these positions or left the legislature are coded as zero. Table A3 in the Online Appendix provides descriptive statistics on MPs' political careers. Tables 2 and 3 present descriptive statistics for key variables in both datasets.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of key variables, Bill × MP dataset

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of key variables, term × MP dataset

Independent variables

To assess the causes (Hypothesis 1) and consequences (Hypothesis 2) of legislative review, we rely on two sets of explanatory variables. To test Hypothesis 1, our main challenge lies in measuring political ambition. The most straightforward way to assess MPs' ambitions for higher office is to conduct surveys with MPs (Hoyland et al., Reference Hoyland, Hobolt and Hix2019; Sieberer and Müller, Reference Sieberer and Müller2017). For our purposes, surveys have at least two drawbacks. First, our analysis dates back well over a decade and MPs' goals are difficult to assess retrospectively due to re‐call error, where legislators are unable to reconstruct their past states of mind and cognitive biases, such that MPs' factual career paths influence their self‐perception in the past. Additionally, elite surveys are increasingly faced with the problem of low response rates (Bailer, Reference Bailer, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014), where one can only construct a survey‐based measure of political ambition for a potentially small subset of responsive and likely unrepresentative members.

Current research relies on somewhat coarser proxy measures to assess politicians' career aspirations. For instance, Meserve et al. (Reference Meserve, Pemstein and Bernhard2009) use age as a proxy for ambition. We are hesitant to include such a measure as age might constitute a fair approximation for future career opportunities, while it is a less direct measure for ambition. Others rely on actual career paths as a measure of ambition, where ambition at time point t is indicated by future career paths (Hoyland et al., Reference Hoyland, Hobolt and Hix2019). This approach suffers from the obvious shortcoming that career ambition and actual career attainment are not identical.

We rely on two measures for career goals. First, we build on work on the U.S. Congress, where political ambition is measured via candidacies (Hibbing, Reference Hibbing1986). We exploit the fact that MPs' career ambitions in sub‐national politics are often not static, as legislators aim to win seats in upper‐level legislatures. This multi‐level setting allows us to relate MPs' candidacies to Schlesinger's (1966) typology of progressive, static and discrete ambition. For each legislative term, we document whether a Landtag MP ran for the Bundestag or the European Parliament (progressive ambition), whether an MP ran for re‐election (static ambition), or if no further legislative mandate was sought (discrete ambition).

This measure of ambition arguably suffers from selection bias, as some MPs might try to win a nomination but fail to get selected. Ambitious MPs might also anticipate that their chances of being selected are low and refrain from seeking a candidacy. In general, measuring a latent trait like political ambition is challenging, such that all current measures are subject to shortcomings. We believe that these shortcomings are less severe when relying on candidacies. There is well‐documented evidence that there is barely any intra‐party competition for re‐nominations in the German case. Baumann et al. (Reference Baumann, Debus and Klingelhöfer2017) study intra‐party competition during the re‐nomination of district candidates for the German Bundestag and conclude that ‘a contested renomination procedure is a relatively rare event for incumbent MPs who seek reelection: Across all parties only slightly more than 10% of MPs had to compete against one or more contenders’ (p. 986). Similarly, Reiser (Reference Reiser and Niedermayer2011) shows that when Bundestag incumbents run for re‐nomination, there is no challenger in 91.5 per cent of cases. In their case study on German state‐level MPs, Best et al. (Reference Best, Jahr, Vogel, Edinger and Patzelt2011) highlight how German parties try to recruit skilled and loyal representatives by minimizing the influence of selectorates on the length of individual mandates to make MP careers as low‐risk as possible (p. 177). Therefore, selection biases should only play a minor role when studying static ambition among incumbents in Germany.

What is more, any selection bias would lead to a more conservative test. We can assume that unambitious MPs will rarely receive a nomination against their will. This means that few progressively and statically ambitious MPs are wrongly classified as having a discrete ambition when they fail to get (re‐)selected. When testing the effect of progressively/statically ambitious MPs versus the baseline (discrete ambition), this would shrink the effect sizes and diminishing levels of statistical significance. Hence, any biases would result in a conservative test rather than in conclusions that are too liberal.

Second, we propose a new measure for political ambition that exploits politicians' social media use. The link between social media use and political careers has been studied from different angles. Broadly speaking, studies can be grouped as answering one of two questions, either ‘Which politicians adopt social media?’ or ‘How do politicians use social media?’. For example, Evans et al. (Reference Evans, Cordova and Sipole2014) investigate the adoption of Twitter among members of the U.S. Congress and find that candidates in competitive races are more likely to have Twitter accounts than those from safe districts. Peterson (Reference Peterson2012) investigates the electoral threat hypothesis using social media data, testing whether members of Congress use social media to strategically improve their re‐election prospects. His analysis shows that the more funds an MP spent in the previous election, the more likely they are to (i) adopt Twitter, (ii) tweet frequently and (iii) adopt Twitter earlier than members who spent less. In their comprehensive study of political Twitter content, Golbeck et al. (Reference Golbeck, Grimes and Rogers2010) find that politicians do not use the platform to provide new insights into government or the legislative process or to improve transparency. Rather, Twitter is used for self‐promotion. In his systematic literature review on the use of Twitter in election campaigns, Jungherr (Reference Jungherr2016) shows that the broader literature is well‐aligned with this finding. Overall, the existing findings are well in line with Twitter being a platform for ambitious politicians who use social media to increase their (re‐)election chances. We construct a binary variable, where MPs are coded as ambitious if they maintain a professional social media profile on either Twitter or Facebook and as non‐ambitious otherwise.

To highlight the link between social media activity and political ambition, we associate the two measures of political ambition to investigate whether they tap into a common underlying phenomenon. As shown in Figure A1 (Online Appendix), most MPs who are classified as ambitious using the candidacy‐based measure receive the same classification based on the social media measure.

The second hypothesis regards the effect of legislative activity on career trajectories. In this analysis, we measure legislative efforts using two indicators. First, we document the number of bills to which a legislator has submitted amendment proposals. Second, to account for the fact that some amendments are more lengthy and signal more engagement than others, we count the total number of article changes that a legislator proposed over the course of a legislative term.

Control variables

We control for several factors that may impact the legislative activity of MPs and their future career prospects. These factors either relate to some bills being more likely to be amended than others and to some MPs being more likely to engage in the legislative review due to factors that are related to but not equal to their ambition.

Regarding bill‐level controls, confounding might result from bills being differently long and complex. In addition, certain policy fields may be more heavily scrutinized than others. We adjust for this possibility by controlling for bill length and the policy field of the proposal. Bill length is measured as the logged number of articles in the proposal. To classify bills into policy fields, we assigned each bill to one policy field according to the Comparative Agendas Project (Breunig and Schnatterer, Reference Breunig and Schnatterer2020). In addition, we control for party resources, which are measured as the logged number of seats that a party won in the previous election, as more MPs and more associated staff mean more resources for working on amendments. Since an upcoming election will bind MPs' resources away from their parliamentary work and towards their campaign efforts, we further operationalize resources as the proximity to the next election. For each bill× MP observation, the time to the next election is calculated as the logged number of months between the introduction of a bill and the next election.Footnote 2 Since past research has shown that government bills are more heavily scrutinized in committees chaired by opposition parties (Fortunato et al., Reference Fortunato, Martin and Vanberg2019), we include a binary indicator for bills which are reviewed in opposition‐led committees. Finally, we include measures for the potential alternative explanations of individual activity due to policy and vote motivations. Regarding policy motivations, these should predominantly – if at all – be present among new MPs who are unfamiliar with legislative proceedings and the abysmal success rates of opposition proposals. New MPs may believe that they can change policy through legislative review. Hence, we incorporate the variable ‘first term’, which distinguishes new from experienced MPs. Regarding vote motivations, we discriminate between MPs from strongly contested districts and those who won their district by a large margin and include a continuous variable measuring the absolute vote share distance between the district winners and the second‐placed candidates.

Regarding MP‐level controls, we add several socio‐demographic characteristics which are known to affect legislative behaviour such as gender (Barnes, Reference Barnes2016), age (Meserve et al., Reference Meserve, Pemstein and Bernhard2009) and seniority (Shomer, Reference Shomer2009). One can reasonably expect that members of the standing committee that is tasked with reviewing a bill will exhibit higher levels of engagement. Therefore, we include a binary variable indicating whether an MP is part of the relevant committee. Moreover, MPs with leading roles in their party group may be more likely to co‐sponsor or draft amendments to give them political weight. MPs' current leadership positions will thus likely affect their level of legislative scrutiny as well as their likelihood of obtaining a leadership role in the future. We include a categorical variable indicating whether legislators currently serve as a parliamentary chair or manager (group leadership position), or whether they act as a committee chair (parliamentary leadership position). Since MPs' future career prospects might not only be affected by their amendment behaviour but also by other legislative activities, we control for the number of plenary speeches and parliamentary questions legislators posed. In addition, different policy fields might be characterized by different norms, where some policy fields might operate more on the basis of legislation than others. In that case, we would observe more amendments for MPs in legislation‐heavy policy fields. Hence, for each bill× MP observation, we quantify the extent to which the policy field of a bill operates on the basis of legislation using a variable documenting the overall number of bills that were introduced in this field across the entire term. As the research on mixed electoral systems has long focused on potential effects of the ‘mandate divide’ (Lancaster and Patterson, Reference Lancaster and Patterson1990; Stratmann and Baur, Reference Stratmann and Baur2002), we distinguish between MPs who obtained their seats by winning their district and second‐placed finishers who entered parliament through a compensatory seat. Finally, as the political ambition of MPs might vary by the characteristics of their districts, we include a dummy differentiating rural and urban districts, as well as a measure of district size operationalized as the logged number of eligible voters.

Regarding the relationship between legislative efforts and career advancement (Hypothesis 2), we control for committee importance as MPs who are already favoured for future promotion by the leadership could be seated on prominent committees, giving them more occasions to draft amendments. It would thus not be their efforts in the legislative review that results in a promotion, but those who are first in line are simply placed in committees that naturally produce amendments. We construct party‐specific measures of committee importance. While there might be some committees that are equally important to all party groups, committees on social and labour affairs, for instance, might be most important to left parties and committees on environmental and climate issues might be most important to green parties. We follow two distinct approaches to construct party‐specific measures of committee importance: First, we count the number of bills that were drafted by the party of an MP and sent to the committee that an MP is seated on (following Mickler, Reference Mickler2013). The straightforward assumption is that parties are most active in those policy fields which are most important to them. Second, for each party, we compute the share of their national manifesto that is devoted to policy fields which are covered by the committee of an MP using data from the Comparative Manifesto Project (following Whitaker, Reference Whitaker2019). Here, the assumption is that parties devote the most space in their manifestos to policy fields that are most important to them.

Analysis

Individual engagement in legislative review

We start our analysis with an investigation of the hypothesized effect of political ambition on legislative review. We model this effect using the bill× MP dataset. Since the first dependent variable is a binary indicator, capturing whether MPs submitted an amendment, logistic regression is appropriate.Footnote 3 The second dependent variable has count properties. Since we have reason to believe that the count will be overdispersed (e.g., if amendments in the early stages trigger more amendments after the committee hearings), we choose negative binomial regression models to predict the number of submitted article changes by opposition legislators.

The dataset has a nested structure, where observations from multiple MPs are nested in bills. As failure to account for nesting underestimates standard errors, we employ both model types in their multilevel variants and allow the intercepts to randomly vary across bills. Substantively, some bills may be scrutinized more than others due to factors unaccounted for by the statistical models. The multilevel approach takes into account potential differences in the amendment activity due to such unobserved features. We begin with intercept‐only models. We observe substantial intra‐class correlations (ICC) of 0.71 (logistic model) and 0.64 (negative binomial model) at the bill level that is only partially accounted for by the bill‐specific controls, justifying the multilevel model specification.

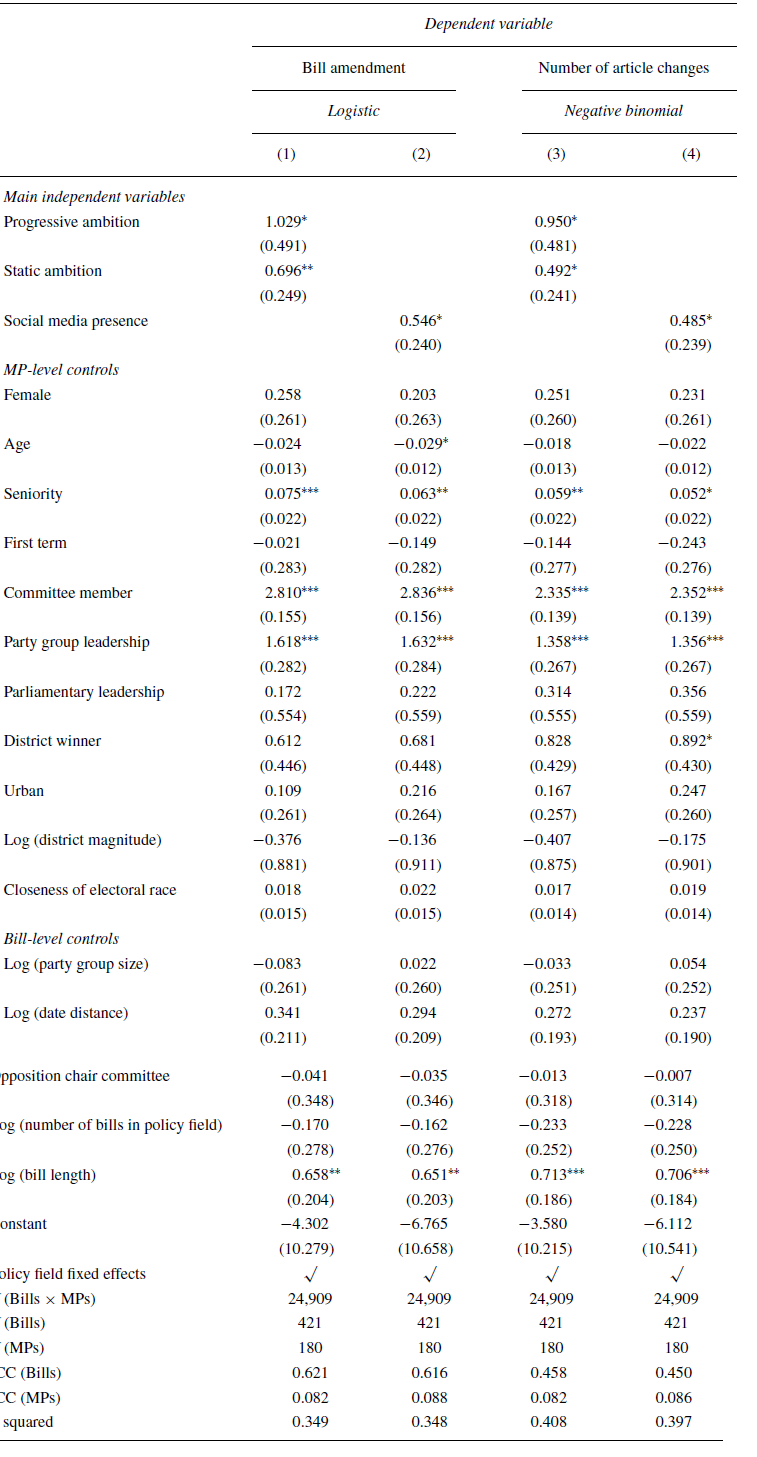

The full models are reported in Table 4 and show robust support for Hypothesis 1. Considering the point estimates for the four statistical models, we find that progressively ambitious MPs are the most active in legislative review, followed by statically ambitious MPs, while those who do not aim to continue their political career are the least active. The effects are stable for both dependent variables when we proxy political ambition with a professional social media presence.

Table 4. Determinants of individual legislative review

Note: The table presents unstandardized coefficients from cross‐classified multilevel logistic and negative binomial regression models with random intercepts at the bill‐ and MP‐level. Standard errors are reported in parentheses.

* p<0.05;

![]() $^{**}$p <0.01;

$^{**}$p <0.01;

![]() $^{***}$p <0.001.

$^{***}$p <0.001.

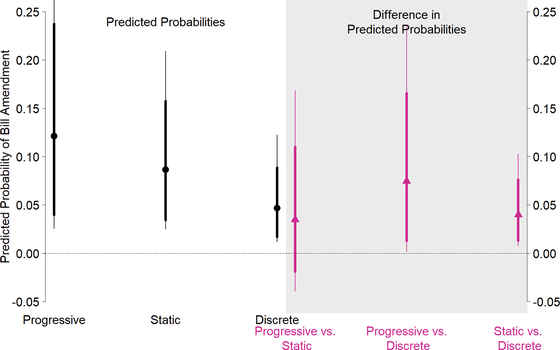

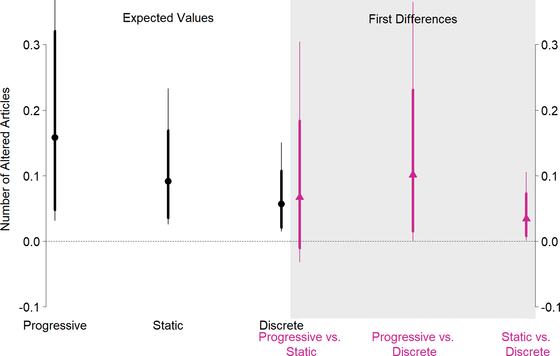

In Figures 1 and 2, we transform the regression coefficients into intuitive quantities of interest and visualize their effects. We account for the estimation uncertainty and take advantage of the framework of simulation‐based inference. First, we simulate 10,000 draws from a multivariate normal distribution defined by the vector of parameter estimates presented in Models 1 and 3 and their covariance matrices as estimated from the models. Next, we use these draws to generate 10,000 predicted probabilities (Figure 1) and un‐logged predicted counts of submitted article changes (Figure 2) for legislators characterized by progressive, static, and discrete ambition. All continuous control variables are held at their means. The rest of the variables are defined such that the predictions represent female legislators who sit on the committee in charge of scrutinizing the bill, represent urban districts and hold no leadership positions.

Figure 1. The effect of political ambition on legislative review, based on Model 1. Dots show the mean predicted probability to engage in legislative review for members of each ambition category. Triangles show the mean differences in predicted probabilities between the three categories. Values are based on 10,000 draws from a multivariate normal distribution defined by the vector of parameter estimates reported in Model 1 and their covariance matrix. Thick bars display the 8.3 per cent and 91.6 per cent (thin 2.5 per cent and 97.5 per cent) quantiles of the simulated distributions. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 2. The effect of political ambition on legislative review, based on Model 3. Dots show the mean expected number of submitted article changes for members of each ambition category. Triangles show the mean differences in expected article changes between the three categories. Values are based on 10,000 draws from a multivariate normal distribution defined by the vector of parameter estimates reported in Model 3 and their covariance matrix. Thick bars display the 8.3 per cent and 91.6 per cent (thin 2.5 per cent and 97.5 per cent) quantiles of the simulated distributions. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The left columns in Figures 1 and 2 present the mean predictions for the three ambition categories along with their 5/6 and 95 per cent confidence intervals (defined as the quantiles of the distribution of the simulations). These allow inferences on the baseline probabilities to engage in legislative review. The right columns report the distributions of the differences in predicted values between the respective categories. The figures suggest that the coefficients in Table 4 also exert substantively meaningful effects. The likelihood of becoming active in legislative review varies considerably between the three types of political ambition, with the mean predicted probability to submit amendments changing from 2 per cent (discrete ambition) to almost 7 per cent (progressive ambition). Given the low baseline probability of observing legislative scrutiny for any particular bill× MP observation, we interpret these changes as substantively meaningful and reasonably large differences between the groups. From the right column of Figure 1, we can see that progressively and statically ambitious MPs exert higher levels of engagement in legislative review than members who did not run for re‐election. The same patterns emerge in Figure 2. Overall, these findings provide robust support for the hypothesis that political ambition exerts a positive effect on the likelihood that members engage in legislative review.

Predicting leadership positions

In a second step, we investigate whether party groups reward MPs' efforts with leadership positions in subsequent legislative terms. The dependent variable measures whether an MP at time t was appointed to a leadership position or was promoted to an upper‐level parliament in term

![]() $t+1$. As the dependent variable is binary, we use logistic regression. The key independent variables measure the overall number of bills or article changes that a legislator submitted to government legislation over the course of term t. Since we have repeated observations with some members appearing in the data more than once, we report cluster‐corrected standard errors.Footnote 4

$t+1$. As the dependent variable is binary, we use logistic regression. The key independent variables measure the overall number of bills or article changes that a legislator submitted to government legislation over the course of term t. Since we have repeated observations with some members appearing in the data more than once, we report cluster‐corrected standard errors.Footnote 4

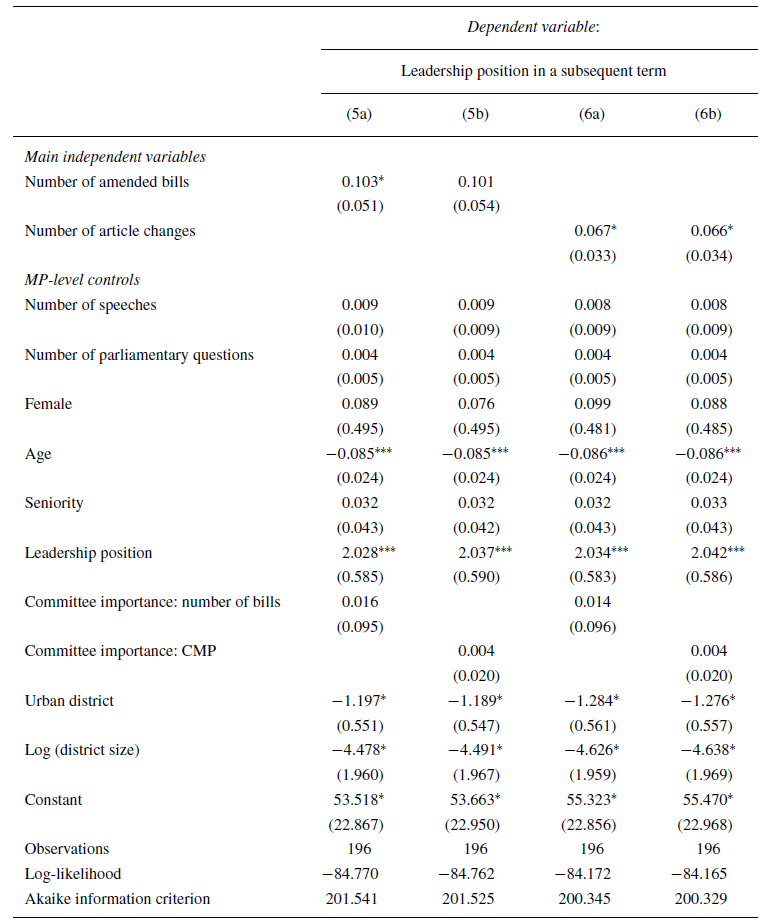

The statistical models are reported in Table 5. The results from Models 5 and 6 suggest that the extent to which opposition legislators engage with legislation has a positive impact on their likelihood of being appointed to a leadership position in the next term. These effects are evident despite controlling for factors such as seniority and the current MP status. From the leadership dummy, we can derive that MPs who already hold a leadership position are far more likely to get appointed to such a position in the next term. Yet, engagement in bill scrutiny increases the likelihood of holding higher office in the future. This is robust evidence for a positive impact of legislative activity on promotion.

Table 5. Determinants of promotion

Note: The table presents unstandardized coefficients from logistic regression models. Clustered standard errors are reported in parentheses.

* p<0.05;

![]() $^{**}$p <0.01;

$^{**}$p <0.01;

![]() $^{***}$p<0.001.

$^{***}$p<0.001.

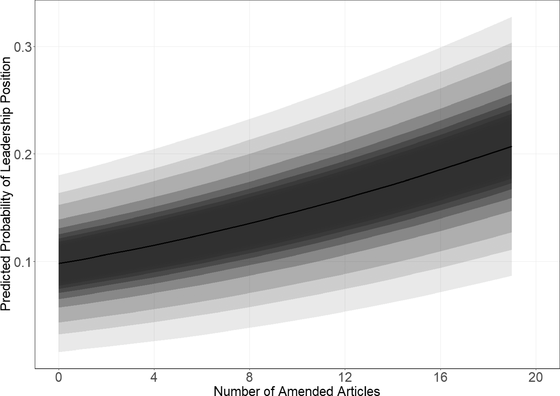

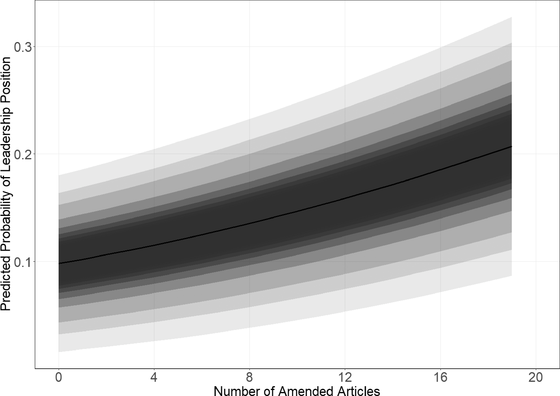

Figure 3 visualizes this effect. The x‐axis captures the number of articles changes that a legislator has submitted in the previous term. The y‐axis represents the predicted probability of holding a leadership position in the next period. The predicted probabilities are constructed as before, based on the estimates from Model 6. We keep all control variables at their observed values and vary the number of amended articles between 0 and 19 for all observations. The figure suggests that the extent to which legislators engage in legislative review clearly shapes their future career prospects as the predicted probabilities rise from 9 per cent (for MPs who submitted no article changes) to 13 per cent (mean value of five submitted article changes) and more than 25 per cent (19 submitted article changes). This effect suggests that parties do take note of MPs' efforts when deciding upon promotions for higher office.

Figure 3. The effect of legislative review on obtaining a leadership position in the next legislative term, based on Model 6a. The solid line represents the mean predicted probability across 10,000 draws from a multivariate normal distribution defined by the vector of parameter estimates and their cluster‐corrected covariance matrix. Error bars indicate the variation of simulated predicted probabilities for various degrees of uncertainty up to one standard deviation.

Conclusion

Drafting and submitting amendments is a resource‐intensive exercise – resources which are in short supply for opposition parties. In addition, most opposition amendments are rejected by the parliamentary majority and this process often takes place behind closed doors. Yet, scrutiny of government legislation by the opposition is surprisingly common in parliamentary democracies. Based on this empirical puzzle, this article sought to shed light on the motivation of opposition parties to scrutinize government legislation.

We proposed an office‐seeking explanation for opposition legislative review. We argued that in a context where the possibilities for individual legislative efforts such as sponsoring private member bills are often limited by the party leadership, ambitious legislators use bill scrutiny to signal their ability to produce policy to their peers and underline their aspirations for higher office. Party leaders rely on these signals and promote active legislators. We collected original data from over 400 government bills in a large German state legislature and found robust empirical evidence for both mechanisms. Opposition MPs who seek re‐election or are nominated for higher‐level parliaments are consistently more active than prospective drop‐outs. Additionally, the most active MPs had the highest likelihood of being promoted in the subsequent term, even after controlling for a large number of competing determinants of career paths.

The study contributes to the research of legislative review in parliamentary democracies. We move away from studying intra‐coalition dynamics in legislative bargaining and provide an explanation for opposition engagement that differs from the commonly described dynamics in the intra‐coalition literature (Martin & Vanberg, Reference Martin and Vanberg2004, Reference Martin and Vanberg2005; Fortunato, Reference Fortunato2019; Pedrazzani and Zucchini, Reference Pedrazzani and Zucchini2013). We also speak to research on political ambition and legislative career trajectories. While this literature has predominantly relied on bill initiation (Chasquetti and Micozzi, Reference Chasquetti and Micozzi2014; Micozzi, Reference Micozzi2014b, Reference Micozzi2014a; Dockendorff, Reference Dockendorff2019; Yildirim et al., Reference Yildirim, Kocapinar and Ecevit2019), we highlight that in contexts where parties are the dominant actors, party leaders rely on other types of legislative efforts to decide upon promotions.

Our contribution raises questions for the analysis of legislative review more generally. Our individual‐level approach to the study of parliamentary scrutiny of government bills could easily be translated to the study of intra‐coalition bargaining. While coalition legislators have been described as watchdogs who police the coalition compromise against deviations due to ministerial autonomy, shifting the attention to the individual raises the question of who polices the coalition agreement. Are backbenchers the workhorses of bill scrutiny or is the review of coalition policy tightly controlled and predominantly exercised by the leadership of majority parties? An individual‐level perspective can provide important nuance to the study of legislative review that would beyond the efforts in this paper.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A previous version of this article was presented at the 14th General Conference of the European Consortium for Political Research, 24–28 August 2020. We are grateful to Tom Louwerse for their helpful comments and suggestions. For excellent research assistance, we thank Felix Münchow, Morten Harmening and Marie‐Lou Sohnius. This research was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) via the SFB 884 on “The Political Economy of Reforms” (Project C7) and the University of Mannheim's Graduate School of Economic and Social Sciences (GESS).

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1: The Landtag Baden‐Württemberg in national compariso

Table A2: The Landtag of Baden‐Württemberg in international comparison

Figure A1: Legislators with and without a Professional Social Media Profile

Table A3: Political Careers of MPs in the Landtag Baden‐Württemberg

Figure A2: Descriptive analysis of legislative efforts for new vs. experienced MPs: Number of submitted amendments

Figure A3: Descriptive analysis of legislative efforts for new vs. experienced MPs: Number of submitted article changes

Figure A4: Frequency of submitted amendment proposals of first term MPs mapped across the legislative period

Figure A5: Absolute vote share distance between the district winners and the second‐placed candidates versus percentage of bills amended

Figure A6: Absolute vote share distance between the district winners and the second‐placed candidates versus number of submitted article changes

Figure A7: Closeness of the electoral race and opposition legislative review.

Figure A8: Visualization of the subsample for the re‐estimation of models M1‐M4

Table A4: Determinants of individual legislative review, last year of legislative term only

Data S1

Data S2

Data S3