Do social media level the playing field for legislative opposition and independent candidates to reach voters in electoral autocracies? Social media have been seen as a great liberation technology (Diamond Reference Diamond2010) that is particularly useful to mobilise disenfranchised citizens (Iwilade Reference Iwilade2013). Recent scholarship on online electoral campaigns has investigated how candidates use social media, but very few have focused on legislative candidates in electoral autocracies, and on how social media use might differ depending on whether candidates are in support of, in opposition to or independent of the regime (Boulianne Reference Boulianne2016; Jungherr Reference Jungherr2016; Stier et al. Reference Stier, Bleier, Lietz and Strohmaier2018). In electoral autocracies, elections and campaigns play a triple role for the regime: they legitimise it (Schedler Reference Schedler2002), they provide the opportunity to co-opt the opposition (Rakner & Van de Walle Reference Rakner and Van de Walle2009) and they offer information on citizens' preferences (Geddes et al. Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018: 150–1). However, even under electoral autocracy, elections also represent a moment of opportunity or ‘brief political openings’ (Bleck & Van de Walle Reference Bleck and Van de Walle2019: 18) that can lead to positive or negative innovations. Thus, understanding whether social media help level the playing field between pro-regime candidates, opposition candidates and those who run independently is paramount, especially in light of scholarship indicating that social media could benefit regimes in similar ways as elections (Gunitsky Reference Gunitsky2015).

In this paper we explore the affordances of social media for Ugandan parliamentary candidates to the January 2021 election. Specifically, we seek to explore two questions. How did opposition, independent and pro-regime candidates use social media in their campaigns? How were candidates' online campaigns impacted by the state's shutdown of social media?

Taking the campaign for Uganda's 2021 parliamentary elections as a case provides a unique opportunity to investigate the role social media can play in electoral autocracies. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the regime called for the campaign to be held through the media and restricted rallies (The Independent 2020). In this context, social media offered parliamentary candidates a way to engage directly with their constituents. The campaign was however marred by manipulation and censorship efforts from the regime's side, with access to social media being shutdown in retaliation to Facebook and Twitter deleting pro-regime profiles that engaged in ‘coordinated inauthentic behaviour’ (Bwire Reference Bwire2021).

Our study relies on a combination of interviews and social media data. Thirty-one winning candidates in the January 2021 parliamentary elections were interviewed in Kampala, Uganda, in April and May 2022. This material is supplemented by interviews of four candidates who were not elected, including one who dropped out of party primaries. The Facebook pages and Twitter accounts of the interviewed candidates and their two runners-up were then collected, thus covering 91 candidates in total.

We find that, although by inciting candidates to use traditional and social media to campaign the regime did reinforce its dominance, opposition candidates adapted their strategies to the situation differently from pro-regime candidates. Although opposition candidates used social media to complement in-person engagement strategies, many pro-regime candidates saw social media as an alternative to using more costly campaigning strategies. All types of candidates were however angered by the regime's deployment of social media manipulation strategies, such as running disinformation campaigns and shutting down social media. This opens questions regarding the effectiveness of deploying such strategies in the context of electoral campaigns.

This study contributes to the literature on electoral autocracy and on candidates' use of social media in electoral campaigns by shedding light on the existing tensions around relying on social media for legislative campaigns under conditions of autocracy. It also enriches scholarship on democratisation and autocratisation by identifying the extent to which the use of social media in electoral campaigns is part of the ‘menu of electoral innovations’ autocracies adopt (Morgenbesser Reference Morgenbesser2020).

The Campaign for the 2021 Legislative Elections in Uganda

In this paper, we focus on the case of the campaign to the January 2021 parliamentary elections in Uganda. On 16 June 2020, about 7 months before election day, the Uganda Electoral Commission announced that due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, mass rallies would be forbidden and candidates should campaign through the media (Uganda Electoral Commission 2020a). The Ministry of Information and Communication Technology and National Guidance immediately highlighted the possibilities traditional media and social media offer for campaigning (Minister for ICT and National Guidance 2020). Following these announcements, the Uganda Electoral Commission introduced a revised electoral calendar – with election day on 14 January 2021 – and ‘Standard Operating Procedures’, limiting possibilities for organising rallies. These procedures kept changing, and were applied unequally: pro-regime candidates faced less oversight from security forces than the opposition (Cheeseman Reference Cheeseman2021, MP13 2021 int.). Towards the end of the campaign period, on 26 December 2020, rallies were suspended in a number of urban constituencies including the capital of Kampala (Uganda Electoral Commission 2020b).

These elections represent an extreme case where candidates had to adjust their campaign strategies, including adopting social media, in a country where internet use is low – 26.7% of Ugandans use internet less than once a month or more (Afrobarometer 2021).Footnote 1 They were not the first time internet and social media were used by at least some candidates. In fact, parliamentary by-elections held in 2017 saw the appearance on the political stage of Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, better known as Bobi Wine, a popular singer from Kampala who was elected to Parliament and who has used social media politically ever since (Muzee & Enaifoghe Reference Muzee, Enaifoghe, Ndlela and Mano2020). He has also managed to mobilise mass protests against the introduction of a tax on social media, and to take the leadership of a political party, the National Unity Platform (NUP) (Wilkins et al. Reference Wilkins, Vokes and Khisa2021). He ran as the party's presidential candidate against the incumbent President Museveni and his National Resistance Movement (NRM) in the presidential elections held together with the 14 January 2021 legislative elections. Museveni was declared the winner amid widespread accusations of fraud and kept the position he has held since 1985, while Bobi Wine came second (Cheeseman Reference Cheeseman2021). NRM won a large majority of the seats in Parliament (319), but NUP emerged as the strongest opposition party, winning 57 seats. The Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), who had played that role since 2006, came in third in Parliament, with 28 seats. Seventy-one seats went to independent candidates, which is not unusual in the Ugandan context (Karyeija Reference Karyeija2019).

The 2021 legislative campaign in Uganda thus represents an extreme case of the use of social media for two reasons. The first is the imposition of Covid-19-related restrictions on in-person campaign activities and the regime's appeal for candidates to use social media. Secondly, this comes just as a new political leader is appearing on the Ugandan political stage, who has himself long used social media. By exploring this case, we contribute to the literature on autocratic survival on the one hand, and the literature on electoral campaigns on the other. Indeed, in the Ugandan case, the role played by social media in legislative campaigns is magnified by the fact that candidates were strongly incentivised to use social media, while the most used campaign strategy – holding rallies – was restricted. This case study offers meaningful insights into the role of social media as both a democratic and autocratic tool.

Legislative Campaign Manipulation Strategies

In electoral autocracies, campaigns are part of the regime's survival strategy, but they can also be considered opportunities for change, either towards more democratic or more autocratic institutions (Bleck & Van de Walle Reference Bleck and Van de Walle2019: 18). Despite the common perception that autocrats rely on a large array of extra-legal tools to manipulate electoral campaigns, such as stuffing ballot-boxes, vote buying (Kramon Reference Kramon2016; Wahman & Seeberg Reference Wahman and Seeberg2022) or violence (Wahman & Goldring Reference Wahman and Goldring2020), autocratic regimes mostly use other manipulation strategies that are also common in democracies (Gandhi & Lust-Okar Reference Gandhi and Lust-Okar2009: 414).

When designing constituencies, the number of seats is frequently extended (Gerzso & Van de Walle Reference Gerzso and Van De Walle2022), so that rural areas traditionally supporting the regime are allocated more seats than urban areas (Boone & Wahman Reference Boone and Wahman2015), and gender quotas are introduced to the same effect (Muriaas & Wang Reference Muriaas and Wang2012). The regime can co-opt elected members of the opposition (Arriola et al. Reference Arriola, Devaro and Meng2021), thus weakening it. The regime can also channel state resources such as a strong security apparatus to cause violence in opposition strongholds or policy-making to increase spending at the constituency level just before elections (Conroy-Krutz & Logan Reference Conroy-Krutz and Logan2012; Brierley & Kramon Reference Brierley and Kramon2020).

To avoid the emergence of strong competitors from within, the autocrat can manipulate competitive primary elections, where the incumbent parliamentarian is not directly supported by the party (Wilkins Reference Wilkins2021: 157). In this system, as in Museveni's Uganda, electoral campaigns are characterised by a number of independent candidates (Rakner & Van de Walle Reference Rakner and Van de Walle2009), many of whom are losing candidates from the dominant party's primaries (Karyeija Reference Karyeija2019; Wilkins Reference Wilkins2019). As presidential and legislative elections are held concomitantly, this also means that pro-regime parliamentary candidates relay the incumbent president's message to their electors (Wahman & Seeberg Reference Wahman and Seeberg2022: 19). This phenomenon is even more prevalent in Uganda, where competing independent candidates in the same constituency are also frequently aligned with the incumbent president (Wilkins Reference Wilkins2019).

Thus, scholarship has identified a large array of strategies deployed by African autocrats during electoral campaigns to ensure both their own re-election and their continued dominance over parliament. Autocrats have become well-versed in using innovations developed in democracies to better subvert democratic processes, such as strategic distraction (Morgenbesser Reference Morgenbesser2020: 1056). Social media could also offer some of the advantages of elections, such as learning citizens' preferences, and information on how the opposition is faring, and at a lower cost than elections for the autocrat (Gunitsky Reference Gunitsky2015: 43).

It is paramount to combine the insights gained from the literature on electoral manipulation with what is known of how social media are used by candidates in legislative campaigns. Although some scholars have highlighted the potential of social media as ‘liberation technologies’ (Diamond Reference Diamond2010), others underline that inequalities in political participation in Africa remain, limiting the liberating potential of social media. Men use social media more than women, both to get information and to participate politically (Ahmed & Madrid-Morales Reference Ahmed and Madrid-Morales2021), mobile network coverage is often limited to urban areas and the cost of data and devices remains high (Chiweshe Reference Chiweshe2017). Additionally, they are not built to foster democratic change, and can be used to facilitate state control of the information environment (Mutsvairo & Rønning Reference Mutsvairo and Rønning2020). This is particularly important in the case of the campaign for the 2021 legislative elections in Uganda, where Covid-19 restrictions forced all candidates to adapt and rely less on political rallies – which are one of the most important strategies in Uganda as in many other African countries – and more on social media, thus running hybrid campaigns (Paget Reference Paget2019).

Social Media in Legislative Campaigns

Most of the literature concerned with the affordances of social media in electoral campaigns has focused on western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic countries, with a few exceptions (Jungherr Reference Jungherr2016; Corchia Reference Corchia2019; Maio & Dionne Reference Maio and Dionne2021). Two competing theories emerge from that literature, one highlighting that social media can serve as an equaliser, as it makes it easier for smaller parties to reach potential voters (Gibson & McAllister Reference Gibson and McAllister2015), while the other emphasises the normalising role of social media, which reproduces existing asymmetries of power (Koc-Michalska et al. Reference Koc-Michalska, Lilleker, Smith and Weissmann2016). Recent systematic reviews reveal that urban candidates use social media more, as do those who compete for well-established parties, providing support to the normalisation theory (Jungherr Reference Jungherr2016; Corchia Reference Corchia2019). However, these focus on electoral campaigns in western democracies, and most often only consider a single social media platform, while cross-platform analyses remain rare (Haleva-Amir Reference Haleva-Amir2021).

Turning to the literature investigating the use of social media by candidates to electoral office in African countries, the findings are unclear. Some studies highlight that social media played an equalising role (Bleck & Van de Walle Reference Bleck and Van de Walle2019: 175), with Facebook lending more visibility to the opposition in Botswana (Masilo & Seabo Reference Masilo and Seabo2015), and WhatsApp enabling usually excluded demographics such as youth and women to participate in campaigns in Nigeria (Cheeseman et al. Reference Cheeseman, Fisher, Hassan and Hitchen2020: 147), and lowering the cost of campaigns for smaller parties in Sierra Leone (Dwyer et al. Reference Dwyer, Hitchen, Molony, Dwyer and Molony2019: 112). Social media can disrupt traditional campaigns, enabling more symmetrical, direct relationships between candidates and citizens (Maio & Dionne Reference Maio and Dionne2021), and facilitating political discussions between commenters, even if heads of state do not actively interact online with those who comment their posts (Bosch et al. Reference Bosch, Mare and Ncube2020). Candidates in other contexts have used social media to organise and bypass traditional media structures (Cheeseman et al. Reference Cheeseman, Fisher, Hassan and Hitchen2020; Mare & Matsilele Reference Mare, Matsilele, Ndlela and Mano2020), which could be significant in Uganda, where traditional media tend to give the word mostly to mainstream men, in a generally hostile political climate (Maractho Reference Maractho, Mutsvairo and Karam2018). In fact, Ugandan radio channels have used Facebook to engage with their audience, after political talk shows had been banned (Alina Reference Alina and Kperogi2023).

Other studies find that social media involve high financial costs for candidates but offer few benefits, as strategies involving personal contact, such as rallies, are seen as much more effective (Ngomba Reference Ngomba, Bruns, Enli, Skogerbo, Larsson and Christensen2015). Similar conclusions are drawn by Mare & Matsilele (Reference Mare, Matsilele, Ndlela and Mano2020: 172) in their investigation of the role social media played in the 2018 presidential campaign in Zimbabwe: rallies and other strategies are more relevant, especially in rural areas, where access to social media is a challenge. All highlight that social media do not replace other forms of campaigning – in particular political rallies. In fact, a study of how Ugandan activists use social media demonstrates that they use them to enhance traditional forms of activism (Chibita Reference Chibita and Mutsvairo2016).

Most studies tend to focus on the use of a single social media service. In their study of the 2014 general elections in Botswana, Masilo & Seabo (Reference Masilo and Seabo2015) analyse a few candidates' Facebook pages, as well as pages linked to media outlets and the government. Maio & Dionne (Reference Maio and Dionne2021) identify Twitter profiles of candidates in the races for the presidency, and for seats as governor, senator and woman representative, while others focus on parties' strategies (Dwyer et al. Reference Dwyer, Hitchen, Molony, Dwyer and Molony2019; Cheeseman et al. Reference Cheeseman, Fisher, Hassan and Hitchen2020). Moreover, they do not account for the potential for the regime to deploy manipulation strategies online or for how other election manipulation strategies might spill into the online campaign.

Manipulating Social Media during Electoral Campaigns

In line with the increased use of social media for campaigning, authoritarian regimes have deployed manipulation strategies targeting social media. In fact, scholarship on online campaigns in electoral autocracies identifies the issue of disinformation, which threatens the fairness of elections (Mare & Matsilele Reference Mare, Matsilele, Ndlela and Mano2020: 172–73). And although the prevalence of ‘bots’ – that is, automated posts, in online campaigns is also well identified (Ndlela Reference Ndlela, Ndlela and Mano2020), neither disinformation nor the use of bots more specifically are analysed as possible regime manipulation strategies.

Some African governments have also used the ‘kill-switch’ during elections, that is, shutdown internet on election day (Freyburg & Garbe Reference Freyburg and Garbe2018). Shutdowns are decided by the executive and implemented by internet service providers (Mare Reference Mare2020). They limit candidates' and their supporters' ability to mobilise on election day and to use social media to monitor the ballot-casting process itself, as was the case in the previous elections in Uganda (Garbe Reference Garbe2024). However, internet shutdowns can lead to protests (Rydzak et al. Reference Rydzak, Karanja and Opiyo2020; Mpofu Reference Mpofu and Kperogi2023), and to the increased use of social media to get the news (Lemaire Reference Lemaire2024). Other manipulation strategies are also deployed beyond protests or elections, for example via legislation restricting online content (Parks & Thompson Reference Parks and Thompson2020), or, in the case of Uganda, introducing social media-specific taxation (Kakungulu-Mayambala & Rukundo Reference Kakungulu-Mayambala and Rukundo2018).

Overall, little is known about how online manipulation strategies affect how parliamentary candidates conduct their campaign. This is particularly important in restricted environments as Uganda, and even more so when campaign opportunities – and especially rallies – are more limited than usual to combat a global pandemic. Our study therefore proposes to explore how parliamentary candidates used social media during to campaign in such restricted conditions.

Methodology

Our analysis builds on 35 semi-structured interviews of candidates in the January 2021 legislative elections in Uganda, combined with the metadata of social media posts published during the campaign on the Facebook Pages and Twitter accounts of the interviewees and those of their opponents who gathered enough votes to place in the top three in their constituency.

Thirty-one of the interviewees were Members of Parliament elected during the January 2021 election. They were interviewed in late March and April 2022 in the precincts of Parliament by one of the co-authors and research assistants. As these respondents are all winners of the campaign,Footnote 2 the two co-authors also interviewed three candidates who ran for elections but were not elected, and one candidate who lost during the primaries. This gives us a total of 35 interviewees. How interviewees were selected, and how interviews were conducted and analysed is described in Appendix A, where Table A.1 summarises the main characteristics of interviewees. The interview guide can be found in Appendix B.

As the interviews were conducted about 15 months after the end of the campaign, we get a more distanced view from candidates, most of them now members of Parliament, but others, having lost in elections, now back in civilian life. This timeframe comes with limitations related to imperfect recall or to interviewees' answers being coloured by newer experiences online. As most interviews were conducted in the Parliamentary precincts, one could question whether interviewees felt they could discuss freely the challenges they met online in their campaigns. However, NRM and opposition Members of Parliament all offered some criticism of the way the campaign was regulated, both online and offline. All interviewees spoke anonymously.

To triangulate findings and broaden our perspective, we supplement interviews with social media data from the online campaign of our interviewees and of their top two opponents. A detailed description of the data collection process is included in Appendix C. We define the online campaign as starting on 16 June 2020, when President Museveni announced the campaign should be conducted through the media and social media. This announcement gave candidates time to organise ahead of the official campaign start on 10 November 2020 (Uganda Electoral Commission 2020a). We choose 18 January 2021 as the end of the campaign, as this marks the day when internet was restored, following the publication of the elections' results (BBC News 2021).

We focus on Twitter and Facebook pages that clearly mention the campaign, as candidates expect publicity if their Twitter profile or Facebook page description mentions they are a (former) candidate or elected Member of Parliament. We only analyse the metadata associated to posts (date and time, number of likes and comments) to protect the anonymity of the candidates. Data collection procedures are described in details in Appendix C.

Although interviewees mentioned using large WhatsApp groups to reach constituents, we chose not to collect data from these as they are not publicly and openly available: one needs to be added by a group administrator. This creates a greater expectation of privacy for members, especially as they discuss sensitive issues under an authoritarian regime (Franzke et al. Reference Franzke, Bechmann, Zimmer and Ess2019; NESH 2019).

Our dataset thus covers 91 candidates in 33 constituencies,Footnote 3 among them 42 who had a Facebook page during the campaign, while 17 had a Twitter profile during the same period. Table C.1 in Appendix C summarises the number of Facebook pages and Twitter profiles identified per party, and the number of posts per page and Twitter profile for which metadata were analysed.

It also contextualises candidates' use of Facebook and Twitter among other social media services, as well as the place of social media within the broader campaign. Although we rely on our analysis of interviews to understand how candidates consider the role social media played in the campaign, we explore social media data graphicallyFootnote 4 to identify trends.

Setting the scene: the social media services candidates used

Turning to the analysis, we will proceed by first identifying the social media candidates reported using for the campaign, then discussing whether it made it possible for them to reach voters, before investigating the place social media took during the campaign, and how candidates were affected by the regime's manipulation efforts.

In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic and restrictions on political rallies, candidates were encouraged to campaign using traditional media and social media (Cheeseman Reference Cheeseman2021). Most interviewees reported having used social media to some extent for their campaign. WhatsApp was the main social media application they used, although Facebook was often mentioned. Only three interviewees reported not using any social media for the campaign. They highlight that it was not useful to reach voters, as their constituency was either non-competitive or too rural. In the words of a rural NRM candidate: ‘My campaign [was] in a rural setting. The issue of social media is more or less silent in my constituency’ (MP4 2021 int.), whereas another explained ‘I did not use social media because it was not reaching my targeted voters’ (MP11 2021 int.).

Although some candidates indicated that they used their personal Facebook profiles (N3 2021 int.; MP13 2021 int.), others mentioned creating Facebook pages to engage with electors: ‘At first, I used my personal account but later on, competitors started misusing it, they were digging pictures from there to use them to confuse my voters, I closed it and opened a new page and centralised it to politics’ (MP30 2021 int.). Here, the candidate highlighted some of the dangers of using one's personal profile. However, most interviewees do not seem to draw the distinction between a personal profile and a Facebook page.

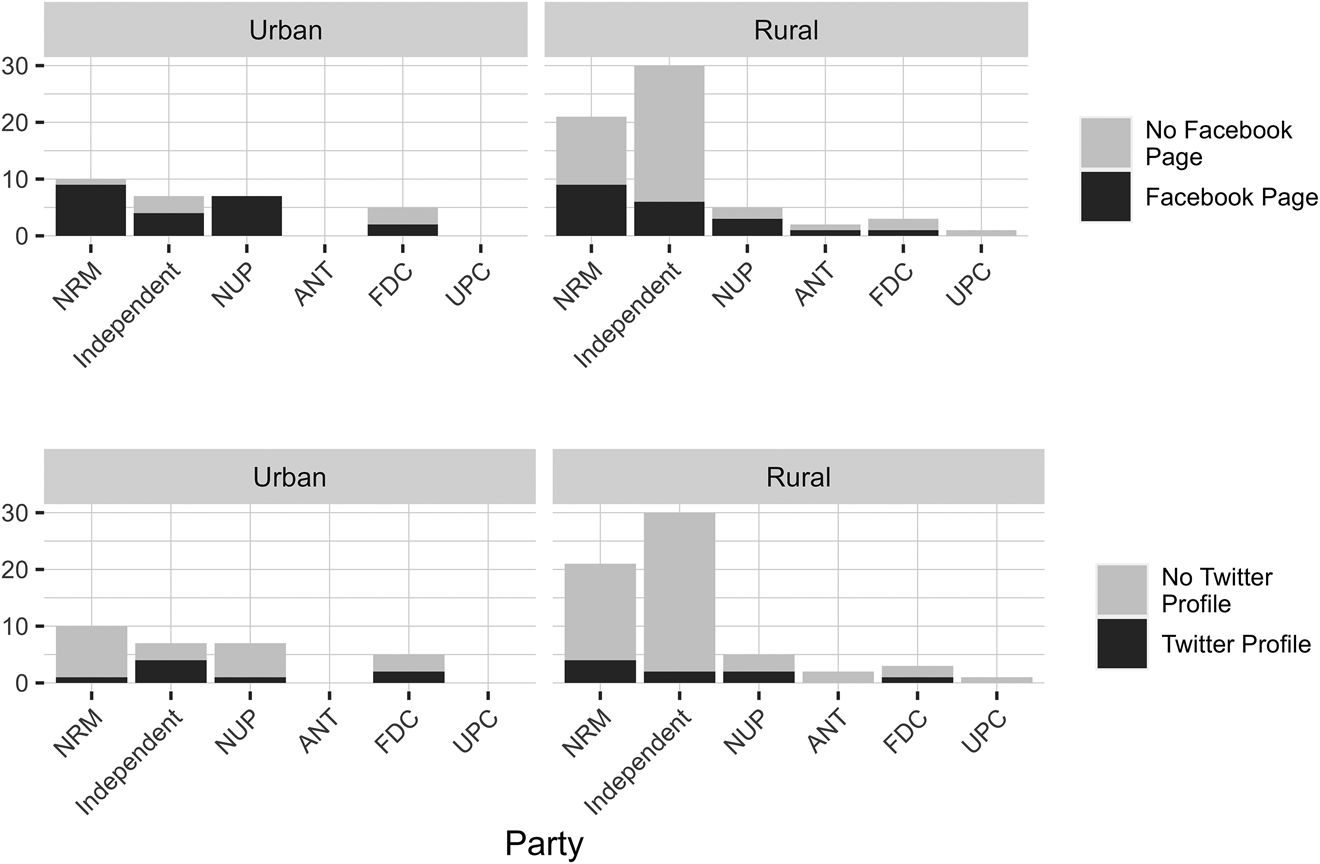

Very few candidates reported having used Twitter. Most of those who did were running in urban constituencies (MP10 2021 int.; MP31 2021 int.; MP30 2021 int.; N2 2021 int.; N4 2021 int.). This is confirmed by the social media data we were able to collect for our sample, presented in Figure 1. Although most urban candidates had a Facebook page in their name (top left quadrant), most rural candidates did not have a page in their name (top right quadrant). All urban candidates for NUP, the main opposition party and almost all urban candidates for NRM, the party in power, had a Facebook page. By contrast, an extremely low number of candidates had a Twitter profile during the campaign, as shown by the two bottom quadrants of Figure 1. It thus remains paramount to contextualise the place of social media among other strategies.

Figure 1. Overview of candidates with a campaign-related Facebook page and/or Twitter profile. Number of candidates for whom we were able to identify campaign-related Facebook pages (top) and Twitter profiles (bottom) per party and type of constituency.

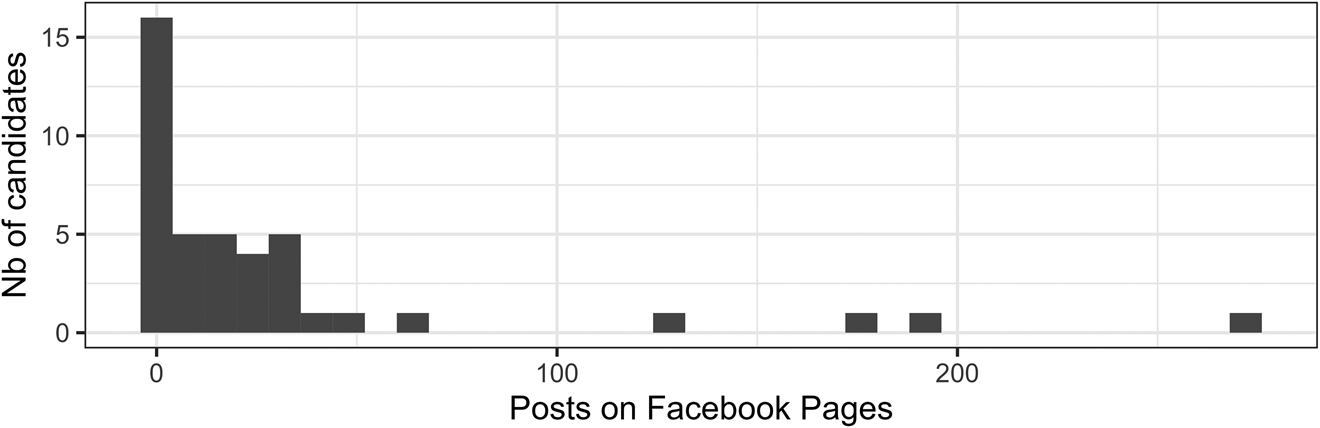

We also find big variations in terms of number of posts per candidate on Facebook pages and on Twitter profiles. The distribution of posts on Facebook pages as shown in Figure 2 is left-skewed: a third of the collected Facebook pages have almost no posts. Things were worse on Twitter. One candidate posted more than 2,200 tweets, over half of the tweets we collected (4,242 in total), whereas most candidates did not tweet at all during the period. What we can learn from Twitter as a source is limited to the online behaviour of just one candidate. We will thus refrain from using Twitter data further, as it is not representative of how the candidates in our sample used social media, and because we also risk re-identifying some of our anonymous interviewees. Data from Facebook pages, however, enable us to explore how candidates from the main parties used this service. Still, these data need to be contextualised, as most candidates used other social media tools to campaign such as their personal Facebook profile or WhatsApp.

Figure 2. Distribution of posts on Facebook pages. Distribution of posts by candidates on Facebook pages (or the period 16 June 2020–18 January 2021).

Accessing Voters Online?

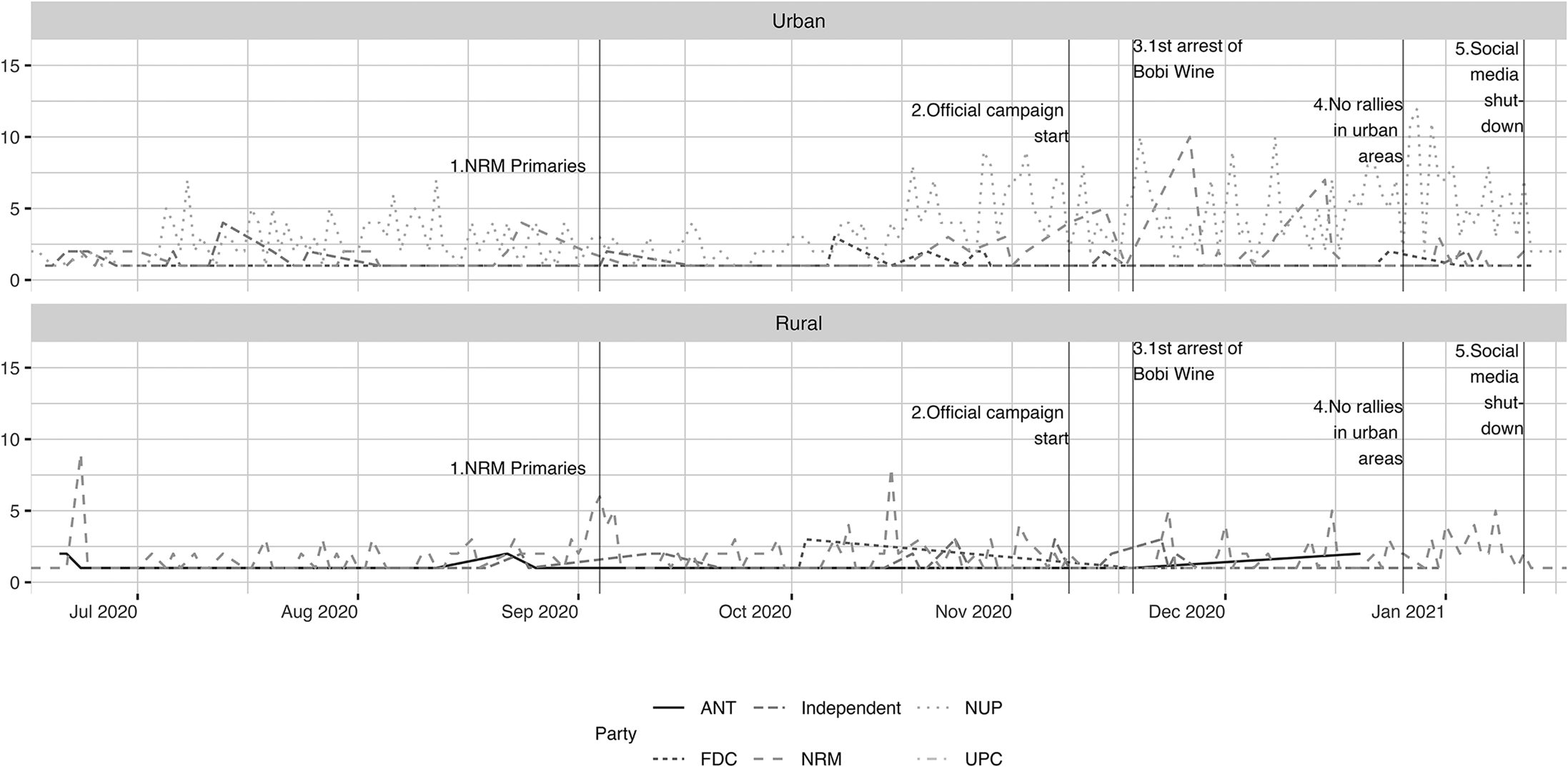

The limited number of Facebook pages and Twitter profiles we were able to identify and collect is reflected in our interview material. Rural constituencies are not well connected to the internet: ‘the challenge is small coverage in Uganda. Network is very poor’ (MP6 2021 int.). Many of our rural-based interviewees mention that social media were not very useful in their campaign. We also find that opposition candidates post a lot less on Facebook pages in rural areas, compared to pro-regime candidates (Figure 3, bottom panel). The imbalance between opposition and pro-regime parties on social media in rural areas reflects the fact that Museveni's regime has drawn much of its support from rural areas over the years, while urban areas are strongholds of the opposition (Wilkins Reference Wilkins2016; Abrahamsen & Bareebe Reference Abrahamsen and Bareebe2021). The limited internet infrastructure in rural areas makes it more difficult for the opposition to campaign against the regime. This mirrors other election manipulation strategies where the electoral map is drawn to allocate more seats to rural areas (Boone & Wahman Reference Boone and Wahman2015).

Figure 3. Number of posts on Facebook pages over time, per party. (1) NRM primaries held on 9 September 2020; (2) official campaign started on 10 November 2020; (3) first arrest of NUP leader and presidential candidate Bobi Wine on 18 November 2020; (4) rallies suspended in urban areas on 26 December 2020; (5) social media shutdown on 12 January 2021.

In addition, using social media represents a high cost for many Ugandans: smart devices are not available to all, and the high cost of data, further increased by social media-specific taxation (Kakungulu-Mayambala & Rukundo Reference Kakungulu-Mayambala and Rukundo2018), means that electors cannot always receive voice or video messages: ‘for rural populations, even getting money to return a message to the sender would be expensive […] many people cannot afford to read long messages’ (N2 2021 int.). The issue of cost of access concerns urban voters too: ‘Actually the poor are more in urban than rural areas’ (N4 2021 int.). The electorate that can be reached via social media is limited to the urban elite.

Reaching electors from one's constituency online is an issue for candidates: ‘it reaches far and wide but you will never be sure whether the people who are exposed to the posts are supporters’ (MP30 2021 int.). Another told us ‘Some people claim they are your target, from your constituency, but actually they are not and they raise issues to which you cannot reply’ (N3 2021 int.). Although not identified as such by our interviewee, this experience might point to competitors paying users to masquerade as constituents and disrupt the campaign in a more or less coordinated manner. The difficulties around accessing social media and knowing whom candidates do reach online might explain the limited use of public platforms such as Facebook and Twitter in favour of the more private WhatsApp, as it allows one to select who receives messages (Bertrand et al. Reference Bertrand, Natabaalo and Hitchen2021: 9).

Overall, calling for candidates to use media and social media instead of in-person meetings made it more difficult for them to engage with their electors. In that sense, social media did not level the playing field, but rather increased inequalities between candidates in two ways. First, opposition candidates struggled to use social media in rural areas, compared to pro-regime candidates. Second, using social media did not help candidates to reach potential voters among the urban poor. Outside of pandemic-related restrictions, when candidates can strategise about how they use the array of tools available to them and combine rallies with the use of social media, electors' limited access to social media and difficulties in ensuring candidates reach their target are less problematic. When in-person campaigning is restricted, their impact is amplified.

The Place of Social Media in the Campaign

Still, most candidates used social media to organise campaign activities and collaborate with their teams: ‘I used WhatsApp to connect with agents who reached [others] inclusive of those offline. […] I used WhatsApp to call for meetings that would be subsequently well attended’ (MP27 2021 int.). Some candidates also used social media in a more interactive way, for example sharing ‘live coverage of ongoing campaigns and related events on Facebook’ (MP8 2021 int.), whereas another candidate had ‘a lot of live Q&A sessions. A lot was going on there’ (N3 2021 int.), and yet another reports using social media to host ‘live talk shows’ (MP22 2021 int.).

The affordances of social media appear in comparisons with two other campaign strategies: traditional media and rallies. NRM candidates see in social media a useful alternative to holding political rallies – and not only in the face of heavy restrictions related to the Covid-19 pandemic. Using social media is ‘cheaper and convenient compared to rallies’ according to a rural NRM candidate (MP5 2021 int.). ‘They are convenient for electors, who do not have to brave “hills or the climate”’ (MP 18 2021 int.), another explained. Social media were seen as a solution to the need for candidates to offer handouts to electors following rallies (MP12 int.), an extremely common practice in Uganda (Conroy-Krutz Reference Conroy-Krutz2017).

The potential for social media to replace rallies was not at all discussed by NUP candidates. This is surprising, as Covid-19-related restrictions on rallies were unequally applied, and the main opposition party, NUP, regularly faced repression by security forces. Its presidential candidate, Bobi Wine, was arrested several times and put under house arrest on 30 December 2020 (Bertrand et al. Reference Bertrand, Natabaalo and Hitchen2021). Moreover, on 26 December, the possibility of holding rallies was suspended in a number of urban areas, including Kampala, which are strongholds for the opposition (Uganda Electoral Commission 2020b).

As such, we expected that opposition candidates would rely a lot more on social media, posting more than others, particularly after the ban on rallies in urban areas. And indeed, they did, as the timeline in Figure 3 shows. We observe that NUP candidates posted on Facebook pages much more than other candidates in urban areas – although candidates running for NRM in urban areas posted more than those running for other parties or as independents. In this respect, it does seem that social media were largely used by the main opposition party when it faced the repression of its rallies.

Therefore, why was using social media as an alternative to rallies not mentioned by our interviewees from opposition parties? They did not refrain from discussing regime repression with us. Some used social media to mobilise their supporters to attend rallies, for example to ‘pass over slogans to voters’ (MP10 2021 int.). Other opposition candidates recount that social media were used to relay information from rallies to others: ‘I was posting the best photos and events by myself’ (MP9 2021). Combining insights from interviews with the evidence presented in Figure 3, opposition candidates used social media to mobilise around rallies, rather than to replace rallies. This is in line with earlier findings on online activism in Uganda (Chibita Reference Chibita and Mutsvairo2016), and makes sense in the case of NUP, a party that emerged following the online campaign of Bobi Wine to parliamentary by-elections in 2017 (Muzee & Enaifoghe Reference Muzee, Enaifoghe, Ndlela and Mano2020).

Instead, they seem to consider social media as an alternative to traditional media. It afforded them the opportunity to overcome difficulties in getting their campaign relayed by traditional media: ‘Direct media were in favour of the regime, those against the government resorted to social media, calls, and texts’ (MP31 2021 int.). This is similar to earlier findings showing that the media gives voice to mainstream candidates (Maractho Reference Maractho, Mutsvairo and Karam2018), and that radio channels themselves have used social media to bypass regime's bans (Alina Reference Alina and Kperogi2023).

Social media enable the opposition to document damaging practices: ‘The graphics of social media were used as evidence in courts of law for bribery’ (MP14 2021 int.). They make it possible for the opposition to communicate effectively about regime repression targeting their supporters: ‘The acts of torture are exposed where security operatives have tortured Ugandans that support positive change’ (MP24 2021 int.). This sentiment was mostly expressed by urban candidates in the opposition, even if other, pro-regime candidates in rural areas mentioned the role of social media in facilitating free speech and affording a cheaper alternative compared to traditional media.

Thus, social media do offer all candidates quick and effective possibilities to communicate with their team. In addition, they offer the opposition an alternative to traditional media, which are often seen as costly and biased in favour of the regime. They do level the playing field in that respect. Even if other opposition candidates used social media to a much lower extent than the two main parties, social media enabled all opposition candidates to reach out to electors and to communicate on repression activities conducted by the regime.

Manipulation and Censorship

Issues of manipulation and censorship also emerge from our data. The latter materialised with the government first blocking social media access and then using the ‘internet kill-switch’ – blocking all internet access. On 12 January 2021, 2 days before polling day, access to social media and messaging applications – including Facebook, Twitter and then WhatsApp – was blocked on the request of the regime (Bwire Reference Bwire2021). President Museveni justified this decision, arguing it was to ensure the campaign remained balanced and accusing social media companies of siding against the regime (Kahungu & Tumusiime Reference Kahungu and Tumusiime2021). Facebook had just announced the suspension of a network of accounts linked to the Ministry of Information Communication Technology and National Guidance. These accounts were coordinating to ‘manage pages, comment on other people's content, impersonate users, re-share posts in groups to make them appear more popular than they were’ – what is also called Coordinated Information Behaviour (Reuters 2021a). Twitter had also removed accounts involved in similar activities aimed at supporting the regime (Twitter Safety 2021). These accounts were described as masquerading as normal users, not as accounts of candidates. Note that the data we collected and present here do not enable us to analyse that phenomenon.

None of our interviewees directly discussed the regimes' manipulation attempts Facebook and Twitter identified. Although in the opinion of some of the NRM candidates we interviewed, social media was blocked because the opposition carried out online abuse, an NRM candidate attributed the shutdown of social media to the fact that ‘youth are always anti-establishment. It is not only in urban areas, they are of course more online. So that is what the opposition is leading to, it leads to closing Facebook’ (N4 2021 int.). Here, the candidate seemed to imply that shutting down Facebook was a way for the regime to control young people, who tend to oppose the regime.

The regime's decision to shutdown social media, the justifications it offered and the fact that Facebook remains blocked to this day in Uganda were all criticised by many candidates, regardless of party affiliation: an NRM candidate recalls: ‘I was upset’ (MP12 2021 int.), and another: ‘Facebook was chopped off … it affected politics and business’ (MP17 2021 int.). Shutting down social media just a few days before the elections increased inequality on the playing field, as candidates had to turn to virtual private networks (VPN) to continue campaigning online. In that context, opposition candidates found it even more challenging to reach electors, and to coordinate in the last few days before the election: ‘It greatly hindered communication and affected the election’ (MP24 2021 int.), in the words of another: ‘I was deeply affected. We could not reach the people’ (N3 2021 int.).

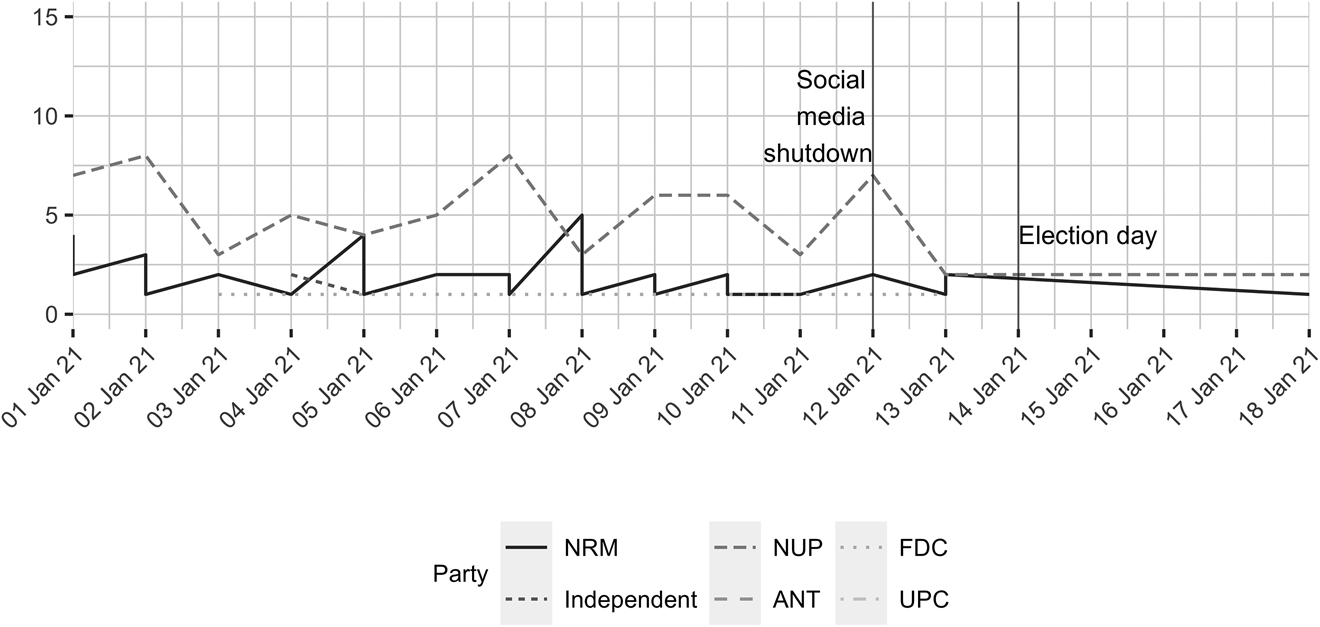

This effect is visible in our social media data, as shown in Figure 4. The number of posts fell abruptly among opposition candidates once social media were shutdown. However, the number of posts by NRM candidates, which had been lower throughout the campaign, remained roughly at the same level. A losing urban NRM candidate recounts: ‘Surprisingly, we had the same number of people [interacting] as we had before Facebook was shut down in Uganda, meaning that almost every user accessed Facebook via VPN’ (N1 2021 int.). VPN use is quite widespread, especially since the introduction of a social media tax in 2018 (Kakungulu-Mayambala & Rukundo Reference Kakungulu-Mayambala and Rukundo2018). It is likely that opposition candidates stopped posting for fear of repression, while pro-regime candidates do not face the same risks.

Figure 4. Timeline of posts on Facebook pages in January 2021.

On the evening of 13 January 2021, just before election day, internet access was entirely suspended (Reuters 2021b), only to be restored on 18 January 2021. Access to most social media platforms – but not Facebook – was restored on 10 February 2021 (Athumani Reference Athumani2021). Internet restrictions on election day were not much discussed among our interviewees. These are a recurrent phenomenon in Uganda (Freyburg & Garbe Reference Freyburg and Garbe2018). It might be argued that this is comparable to the widespread practice of not allowing campaign activities while polling is in progress, as is the case in many democracies. However, this makes it a lot more difficult for candidates to organise monitoring of activities at polling stations and to report on mismanagement.

Many candidates – NRM and opposition – identified another challenge faced during the campaign online: that of disinformation and harassment. It appears to be widespread, regardless of party affiliation. A striking example was given by a losing, urban NRM candidate, who mentions ‘the unfair occurrences that happened to the son of presidential candidate Robert Kyagulanyi [Bobi Wine, NUP] at school when social media was used to accuse him of drug abuse’ (N1 2021 int.). Such attacks against presidential candidates can have a demoralising effect on parliamentary candidates, who are an important part of the presidential campaign, and rely on its messages to advance their own campaigns (Wahman & Seeberg Reference Wahman and Seeberg2022). That a pro-regime candidate cites disinformation against the main opposition presidential candidate indicates how widespread the phenomenon was, particularly against the opposition. Candidates felt it was not possible to effectively counter disinformation: ‘you need to make phone calls to people because they believe what is online’ (N3 2021 int.). Based on the data collected, we cannot evaluate whether the accounts Facebook and Twitter suspended for coordinated inauthentic behaviour were also engaging in harassment. However, the former is certainly part of disinformation strategies.

Social media thus offer authoritarian regimes the opportunity to observe how opposition candidates fare, whether and how their electors engage with them, and to manipulate information available to citizens. Although we can observe part of these activities by interviewing candidates and exploring their public online presences, manipulation efforts are a lot more difficult to detect and attribute. Worse, it appears that when opposition candidates fare too well online or when manipulation is denounced, then the regime will intervene more forcefully to maintain its dominance by blocking access to social media for a long period of time. Of the services we could investigate, the more popular of the two – Facebook – has remained blocked since those elections.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this article, we have explored the affordances of social media for candidates to the 2021 legislative elections in Uganda, relying on insights gained from interviews with 35 winning and losing candidates, and from the quantitative analysis of social media data from these candidates' and their opponents' Facebook pages and Twitter profiles. This approach enables us to better understand the overall online campaign ecology, beyond just one social media application.

Methodologically, we show the importance of contextualising social media services to understand the external validity of the data collected. In our case, although we could collect data from Facebook pages and Twitter, almost all the candidates we interviewed also used WhatsApp. In some cases, WhatsApp was the only social media service they reported using. Similarly, many used their personal Facebook profile, for which data cannot be collected on a large scale. Thus, combining social media data with candidate interviews is what lends internal validity to our study, and we hope to see more studies combining data collected via platforms with other data sources.

The extreme case of the campaign conducted under Covid-19 restrictions provides us the opportunity to study how electoral autocracies adopt new tools to control elections, as well as the challenges they face from the opposition. In Uganda, the pandemic meant that all candidates had stronger-than-usual incentives to use social media in the context of the rise of a new opposition leader. Although the pandemic is exceptional, in the words of one of our interviewees, ‘during lockdown, there was no option so everyone turned to social media and now we cannot take it away’ (N3 2021 int.). Thus, the role social media played is not specific to the case at hand, although it was magnified by the pandemic.

We find that the regime's decision to incite candidates to use traditional and social media to campaign did reinforce its dominance. Opposition candidates adapted their strategies to the situation differently from pro-regime candidates. At the same time, both opposition and pro-regime candidates were angered by the regime's deployment of social media manipulation strategies, including running disinformation campaigns and shutting down social media.

First, access to internet and social media is limited to citizens in urban areas who can afford the high costs of data and devices. Here, the regime manipulates the internet infrastructure to limit opportunities offered to the opposition, and manipulates the cost of connection by implementing social media-specific taxes (Kakungulu-Mayambala & Rukundo Reference Kakungulu-Mayambala and Rukundo2018). The combination of regime dominance in rural areas with connectivity difficulties for both citizens and candidates produces an unlevel playing field that we observe particularly well online. NRM candidates are the only ones who seemed to be posting regularly in rural constituencies. These aspects are a form of exploitation of urban–rural differences by electoral autocracies (Boone & Wahman Reference Boone and Wahman2015).

Second, opposition candidates in urban areas used social media more than pro-regime urban candidates, up until the social media shutdown. For opposition candidates, social media were an alternative to traditional media, which they experience as biased in favour of the regime. A similar strategy was adopted by radio channels themselves when facing regime restrictions (Alina Reference Alina and Kperogi2023). Opposition candidates used social media to mobilise for rallies and enhance their campaign, as Ugandan activists have done during protests in the past (Chibita Reference Chibita and Mutsvairo2016). This contrasts with how rural NRM candidates saw social media – as a cheaper and more convenient way to replace rallies. Regime dominance plays out online and offline: although opposition candidates used the social media to counterbalance restrictions, NRM candidates could afford to choose a strategy over another.

Third, candidates from all affiliations were angered by the regime-imposed shutdown of social media, and later, internet, and denounced disinformation campaigns. This is expected of opposition candidates. It is however more surprising from pro-regime candidates, who could have more readily bought into the regime's justification that the aim was to ensure a level-playing field, especially as they benefit from other forms of regime campaign manipulation strategies.

Although elections in autocracies offer information to the regime on how it performs (Geddes et al. Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2018: 150–1), and legislative elections held concomitantly to presidential elections strengthen the incumbent president's campaign (Wahman & Seeberg Reference Wahman and Seeberg2022), regime-affiliated legislative candidates first and foremost campaign for themselves. Being hit by regime restrictions, such as social media shutdowns, leads pro-regime candidates to express their disagreement during our interviews, and could potentially lead to their support wavering over time. Additionally, it appeared somewhat ineffective, as candidates in urban areas reported being surprised to see their constituents continue to interact on social media – showing that at least some candidates and some citizens know how to bypass such restrictions.

Our findings complement other studies of campaign strategies in electoral autocracies. By focusing on how legislative candidates use social media to campaign, we show how social media offer opportunities for opposition candidates to bypass some of the existing regime restrictions. However, when regimes rely on blunt instruments to control social media – in particular shutdowns – they garner critique from all types of candidates, potentially limiting the benefits they normally draw from elections. It is beyond the scope of our study to evaluate whether relying too frequently on social media manipulation strategies that affect all candidates – and not just those running in opposition – can threaten the autocrat's hold on power. However, some studies have shown that shutting down internet can lead to an increase in how much citizens use social media to get information (Lemaire Reference Lemaire2024).

Comparative work is needed to better evaluate under which conditions the opposition can challenge incumbent regimes online, and the extent to which regimes are able to exploit the opportunities offered by social media before they achieve such control as to render social media useless for observing the opposition and learning citizens' preferences.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X25000102.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.