Background

During the late 1930s, one of the key aspects of the Third Reich's policy concerning Gdańsk Pomerania was its deliberate, pre-war plan of physical elimination of selected sections of the population of the Second Polish Republic, which was established in 1918. Following the invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, the Nazi organisers of the mass executions were intent on transforming Polish Gdańsk Pomerania into German Western Prussia.

The first citizens to be targeted for execution were the educated and elite members of Polish society, including teachers, priests, doctors, lawyers, scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs and community organisers, collectively called the intelligentsia. The next stage was the execution of the mentally ill and physically disabled. Today, it is estimated that 30 000–35 000 victims were murdered between September 1939 and January 1940 in the Gdańsk Pomerania region alone. This number included about 600 Pomeranian Jews (Bojarska Reference Ceran, Mazanowska and Tomkiewicz1972).

Taking into account the types of crimes committed by the Nazis at the onset of the Second World War, some Polish historians pointed out that previous terms and concepts did not fully describe the total theme of the crimes that took place (Kobiałka Reference Kobiałka2022). Hence, the term ‘The Pomeranian Crime of 1939’ was coined (Ceran et al. Reference Ceran, Mazanowska and Tomkiewicz2018), which includes all Nazi crimes committed during the first months of the Second World War in Gdańsk Pomerania.

The mass executions typically took place in remote, hidden areas (e.g. forests), where the bodies of the victims were buried in mass graves. It is impossible to estimate the full scale and scope of the crimes. The main reason is that the perpetrators made a concerted effort to physically cover all evidence of the crimes; any associated documents had already been burned and destroyed by the end of November 1939. During the second half of 1944, a special Nazi commando had the task of locating mass graves in Gdańsk Pomerania, exhuming the corpses of victims and cremating the remains (Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2013).

The materiality of crime and covering up its traces

The project is considering the ‘history of the crime’, research on social memory and commemoration of victims (‘an ethnography of the crime’) but the main element of the project is the archaeology used to search for material traces of the Nazi crimes of autumn 1939 and evidence of the cover-up in 1944 (Kobiałka et al. Reference Kobiałka, Ceran, Mazanowska, Wysocka, Czarnik, Nita, Kostyrko and Jankowski2024).

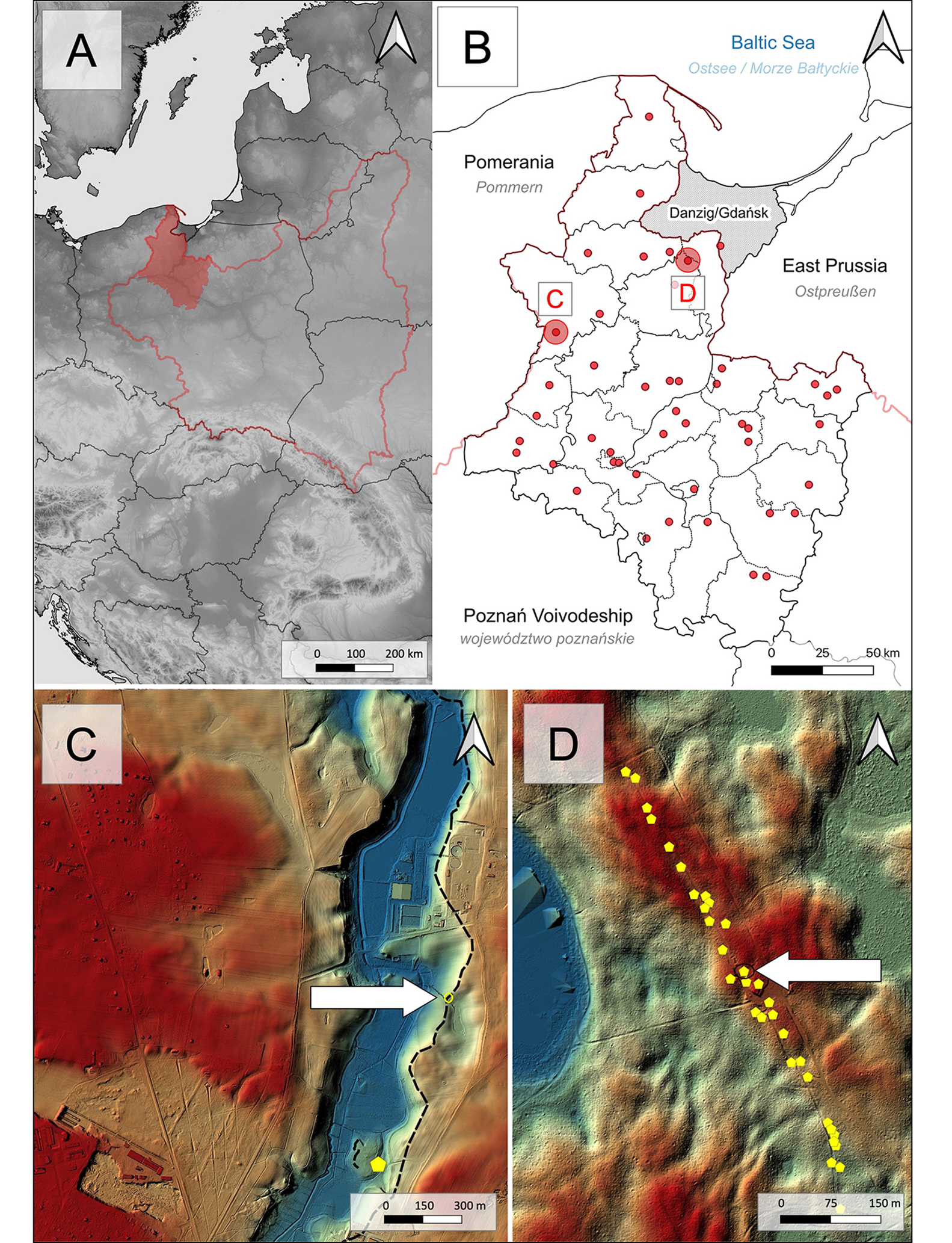

In 2023, field research was conducted at two mass-execution sites in Poland (Figure 1)—one was at ‘Death Valley’ in Chojnice. It was generally known that during the summer of 1939, in anticipation of defending Poland in a war against the Third Reich, the Polish Army dug a military trench system on the northern outskirts of Chojnice (Figure 2), which was several hundred metres long in total (Kobiałka Reference Kobiałka2022). Information of the trench's whereabouts had been gathered from archival post-war eyewitness testimonies and still-living residents of the town; however, the exact location was not known until archaeological research began at the site (Kobiałka et al. Reference Kobiałka, Kostyrko, Wałdoch, Kość-Ryżko, Rennwanz, Rychtarska and Nita2021). The project's use of lidar data, historical aerial photos, metal-detector surveys and excavations made it possible to pinpoint its location.

Figure 1. The studied area: A) the pre-war Pomeranian Voivodeship (in red) and the area of the Second Polish Republic; B) the pre-war Pomeranian Voivodeship with the most important execution sites from the autumn of 1939 (red dots); C) Death Valley in Chojnice—the arrow indicates a fragment of the excavated military trench used as a mass grave; D) Szpęgawski Forest—rhombuses are the (supposed) location of mass graves, the arrow indicates the excavated spot (figure by K. Karski & M. Kostyrko).

Figure 2. Death Valley: A) opening the trench; B) location of the trench in the local landscape (photographs by D. Frymark).

During the Second World War, the trench became a mass grave for the local intelligentsia, the mentally ill and representatives of the Chojnice Jewish community. In the autumn of 1945, Polish authorities carried out exhumations in the surrounding fields; the corpses of 107 people were found (including 15 Jews) and 61 skulls of the mentally ill (Kobiałka Reference Kobiałka2022). During the 2023 field research, less than 5m of the trench system was uncovered (Figure 3). The human bones recovered that year were what was left behind following the post-war exhumations.

Figure 3. Mass grave in Death Valley: A) excavating the grave; B) aerial photograph of the grave (photographs by D. Frymark).

Nine casings, 7.65 × 17mm Browning, from a German handgun were found plus 10 bullets—eight of them were from a 7.65 × 17mm Browning, one was a 9mm Parabellum and the poor state of preservation of the others meant that the calibre could not be precisely measured. These items were found in the grave, therefore it can be concluded that the executions took place at close range—probably at point-blank range—with a single shot straight to the victim's head. Personal belongings of the victims were also discovered in the grave, including gold-plated cufflinks, which indicates that the victims were most likely representatives of the local intelligentsia. Other items uncovered at the site, which also served as material evidence of the crime, include Polish pre-war coins, civilian buttons, a razor, a toothbrush and fragments of clothing (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Material evidence of the crime in Death Valley. A) pistol casings; B) a gold-plated cufflink (photographs by D. Frymark).

The second mass-execution site examined in 2023 was in the Szpęgawski Forest, where a reported 2413–7000 human beings were taken and murdered by the Germans between September 1939 and January 1940. That mass execution also targeted members of the local intelligentsia, the mentally ill, general labourers and farmers, among others (Kobiałka et al. Reference Kobiałka, Ceran, Mazanowska, Wysocka, Czarnik, Nita, Kostyrko and Jankowski2024).

Between the end of October and the end of December 1944 in the Szpęgawski Forest, the Nazis were trying to erase all evidence of the crime. The exhumation commando extracted the corpses of victims and cremated their remains. In October 1945 and May 1947, Polish authorities carried out further exhumations in the Szpęgawski Forest.

The 2023 field research made it possible to analyse and document the Nazi's process in attempting to eliminate all evidence of their crimes at the mass-execution site. A burial pit 10m long, 4.5m wide and more than 2m deep was excavated (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Mass grave in the Szpęgawski Forest: A) excavating the grave; B) close-up of the layer consisting of burned human remains, artefacts and charcoal (photographs by D. Frymark).

It is important to note that even though the Nazi commando had already exhumed the mass grave before the end of the war, a few intact human remains were still found at the bottom of the burial pit. Crucially, the cremated human remains were not deposited at the bottom of the pit as expected but, instead, at the most top layer—up to 500mm thick. As a result of the research, almost 1400kg of burned human remains were secured, the condition of which suggests that the corpses were burned at a relatively low temperature.

The Nazis had robbed the murder victims of their personal belongings, first during their arrest and again just before their execution. However, not all personal valuables had been confiscated from the victims at the time of their death, indicated by the discovery of gold wedding bands and single gold dental crowns in a layer of human ashes. Most of the discovered material evidence included buttons (both military and civilian), various types of belt buckles and clasps, Polish pre-war coins, bullets and casings for German handguns, along with medallions with the image of the Virgin Mary and crosses with the image of Jesus Christ (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Material evidence of the crime in the Szpęgawski Forest: A) a wristwatch; B) burned human remains and a cross (photographs by D. Frymark).

Conclusion

This project encompasses scientific, social, cultural and judicial dimensions—demonstrating the crucial role of archaeological methods in investigating crimes against humanity from the Second World War.

Acknowledgements

The project is funded by the National Science Centre, Poland (UMO-2021/43/D/HS3/00033).