When authoritarian regimes undertake reform, do they enhance their international legitimacy? Theories of autocratic regime survival have long suggested they do; in fact, one reason such regimes undertake reforms may be to build external legitimacy in a post–Cold War world dominated by democracies.Footnote 1 Surprisingly, however, this core assumption has rarely been tested—particularly across reform types and types of benefits presumed to flow from external legitimacy.

Existing studies that do test it generally focus on one type of reform or policy change, and they come to different conclusions. For example, Bush and Zetterberg find that authoritarian regimes gain reputational boosts from instituting electoral gender quotas and increasing women’s descriptive representation.Footnote 2 By contrast, Nielsen and Simmons find little evidence that regimes (of any type) gain international praise and acclaim from ratifying human rights treaties.Footnote 3 Are gender-focused policy changes unique, then, in generating legitimacy for authoritarian regimes? Or might these different results stem from different methods and outcome variables?

Clarifying if and when reforms enhance legitimacy is important because it builds knowledge about how authoritarian regimes survive and adapt. This research contributes by testing the logic across three original survey experiments, conducted iteratively over nationally representative samples of US respondents. All three tested the foundational hypothesis under differing and increasingly tough conditions (see Q1), while the latter two also aimed to provide answers to several more nuanced and currently unanswered questions (Q2–4):

-

1. Do authoritarian reforms enhance external legitimacy (foundational hypothesis)?

-

2. What are the benefits that arise from increased legitimacy?

-

3. Do legitimacy benefits depend on the perceived quality of the reforms, prevalence of critical assessments, and/or characteristics of the regime?

-

4. Are some types of reform more effective at generating external legitimacy than others?

Each experiment presented respondents with hypothetical authoritarian regimes in the Middle East to evaluate, and captured the impact of undertaking reforms on dimensions of external legitimacy. External legitimacy is defined here in conventional terms of support and acceptance from the perspective of international audiences.Footnote 4 As I will show, the concept is used widely in the literature concerning why authoritarian regimes undertake reforms, particularly in reference to the intangible rewards that such regimes are theorized to obtain as a result. This research follows in that tradition, and it also aims to clarify what is meant by the idea of regimes “gaining legitimacy” by probing effects of reform on different types of benefits.

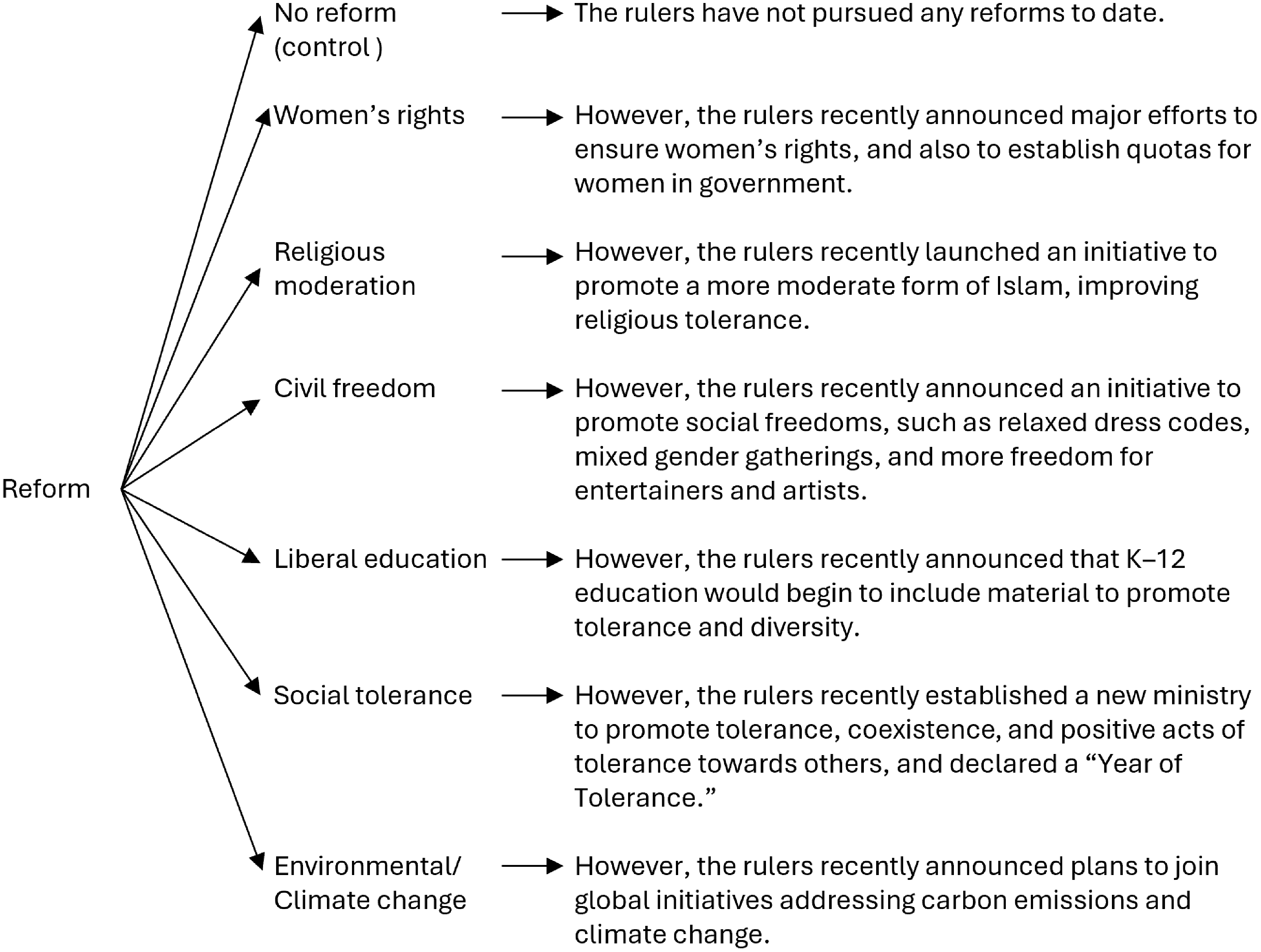

The first experiment tests the foundational hypothesis with respect to a variety of reforms. It adopted a simple independent groups experimental design, identifying the effects of different reforms that were based on real ones recently undertaken by authoritarian regimes in the region. Prioritizing external validity, these included reforms involving women’s rights, education, climate change, and social freedom, as well as a no-reform control condition. After reading the vignette describing the authoritarian regime, respondents reported their overall level of favorability toward it on a feeling thermometer.

But “favorability” is only a first-cut indicator.Footnote 5 Thus drawing from literature on international incentives for reform, the second experiment operationalized legitimacy in terms of both positive benefits (for example, overall favorability, support for increased trade relations) as well as shielding benefits (for example, reluctance to cut ties or boycott the country’s products). While reforms were predicted to generate both types, positive benefits were theorized to be stronger and more reliable than shielding benefits.

Importantly, this second experiment adopted a conjoint design and therefore constituted a harder test for the foundational hypothesis. While the randomly assigned reforms were identical to those in Study 1 for consistency’s sake, this experiment varied important background factors for each regime, including those theorized to reduce external legitimacy (such as how repressive the regime is). Should reforms continue to enhance legitimacy under these more diverse conditions, the case for the foundational hypothesis’s generalizability will be stronger. Study 2’s conjoint design also allowed an investigation of theoretically relevant contextual cues, such as skeptical reactions to the reforms themselves and their quality in terms of whether technical expertise was involved.

The last experiment (Study 3) used the same conjoint design as Study 2 and set of outcome variables (and therefore plays an important replication function). However, it focused on assessing the role of reform type. Reforms and policy changes were divided into two theoretically motivated categories: inward-facing and outward-facing. The former included democratic (or “pseudodemocratic”) reforms in domestic politics, such as improving the quality of elections, and the latter included efforts to reduce global poverty, advance science cooperation, and tackle climate change. Inward-facing reforms were theorized to produce stronger gains because they may be costlier and indicative of deeper commitment. For a real-world comparison, Study 3 also included a nonhypothetical country: Saudi Arabia.

Overall, across all three experiments, the results were remarkably consistent. They suggest that reforms do enhance external legitimacy for authoritarian regimes, at least in the eyes of one important audience—the US public. Nearly all reforms were effective, whether the gains were measured in terms of simple favorability (Study 1) or in more complex terms of positive and shielding benefits (Studies 2 and 3). These gains were also quite robust in that they generally arose regardless of authoritarian regime type, repressiveness (depth of autocracy), wealth, culture, economic development, and geopolitical value to the United States. Skeptical reactions to the reforms themselves reduced the gains, but did not eliminate them, and reliance on technical expertise to implement the reforms played little role.

The findings also yielded new insights about authoritarian reforms and external legitimacy. Positive benefits proved more reliable than shielding benefits, and inward-facing reforms emerged as more powerful than outward-facing ones. Notably, the findings suggest that reforms strengthening women’s rights do exert a uniquely powerful impact—a result consistent with arguments about why such reforms, in particular, have diffused so widely among authoritarian regimes in recent years.Footnote 6

Taken together, these results contribute in several ways. Empirically, they substantiate a presumed causal link in research on international incentives for reform by showing that authoritarian regimes are indeed rewarded with heightened legitimacy for their reform efforts. At the same time, authoritarian regimes appear to have many options—and striking flexibility—in this arena, given that a variety of reforms well beyond those enhancing democracy can produce these benefits. This suggests a widening opportunity for selective norm compliance. Finally, the research offers new insights about which reforms are most likely to enhance legitimacy, and when, including results that complement recent arguments proposing a uniquely powerful role for gender equality reforms.

Background and General Theory

In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), a highly autocratic yet reform-minded state on the southeastern end of the Arabian Peninsula, a group of advisors met to discuss a recent request from Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, then Abu Dhabi’s crown prince and de facto country head. Hailing from some of the world’s top universities and consulting firms, they were enlisted to help UAE ruling elites with reform efforts, from revolutionizing education to pioneering clean energy. But at this meeting, the advisors were stumped. As one recounted, they had been told, “We want to be one of the top five countries,” without further clarification, and left to develop a plan—so they “spent months in that boardroom trying to figure it out!”Footnote 7

This advisor’s recollection highlights the interest many authoritarian governments presumably have in how they are perceived internationally—as well as the key role some envision for their reform efforts in that reckoning. Scholars have long argued that reforms can help authoritarian regimes gain external legitimacy, enhance their reputations, and polish their images in the eyes of international audiences.Footnote 8 In this research, external legitimacy serves as the anchor concept. Arguably, it aligns best with language used in the broadest sweep of research, but studies using related language of reputation, image, and respect are also very relevant.Footnote 9

External legitimacy is defined here in conventional terms of support and acceptance from international audiences.Footnote 10 But legitimacy is, of course, a complex concept associated with both moral and normative as well as empirical research traditions.Footnote 11 Broadly, and following Weber’s descriptive turn, the concept connotes aspects of rightful authority, lawfulness, value alignment, and noninterference, and shares an affinity with Easton’s concept of diffuse system support.Footnote 12 For example, a regime’s domestic or internal legitimacy typically refers to its own citizens’ perceptions of its “right to rule,” while the legitimacy of international organizations has been defined as “the belief by an actor that a rule or an institution ought to be obeyed.”Footnote 13

In the current research, the concept of legitimacy is applied in similar ways in that it is understood as subjective and relational, a perception on the part of an important audience, and a desirable attribute from the perspective of governing authorities. While a government’s external legitimacy does not impose a “duty to obey” on international audiences, it does suggest widespread international acceptance and support, and acknowledgment of that government’s sovereignty and related right to noninterference.Footnote 14 As Easton argued, such acceptance “forms a reservoir of favorable attitudes or good will that helps members to accept or tolerate outputs to which they are opposed or the effect of which they see as damaging to their wants.”Footnote 15 As a result, authoritarian regimes have strong incentives to enhance their external legitimacy, especially in an international system dominated by democracies.

Indeed, the most influential line of thought regarding authoritarian reforms and external legitimacy emerged after the Cold War. In this view, in a changed international setting where democracy seemed triumphant, many authoritarian regimes adapted by appearing to adopt some aspects of democracy. Even with their flaws, elections and other pro-democratic reforms looked like progress, and helped these regimes to “legitimize themselves in the eyes of their citizens and of the international community.”Footnote 16 As Diamond observed in a much-cited issue of the Journal of Democracy, “the term ‘pseudodemocracy’ resonates distinctively with the contemporary era, in which democracy is the only broadly legitimate regime form, and regimes have felt unprecedented pressure (international and domestic) to adopt—or at least to mimic—the democratic form.”Footnote 17

This logic also extended to outward-oriented reforms and policy changes. For example, Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui argued that “governments often ratify human rights treaties as a matter of window dressing.”Footnote 18 In authoritarian regimes, specifically, “ruling elites might ratify a treaty to gain legitimation in international society, putting little effort into aligning their behavior with the treaty provisions.”Footnote 19 Likewise, electoral autocracies increasingly adopted the policy of inviting international election observers. Hyde argues this new direction was intended to “increase their share of internationally allocated benefits,” including both tangible benefits such as foreign aid and intangible ones such as legitimacy.Footnote 20

Not all arguments emphasize a calculated effort at regime survival, or specifically democratic/“pseudodemocratic” political reforms. For example, using ethnographic evidence from palace settings, in earlier work I found that UAE ruling elites pursued liberal reforms in education and citizen-building in part because they were inspired by their own personal experiences living and studying in Western liberal democracies.Footnote 21 Those experiences “supplied them with powerful, sometimes uncomfortable, ideas about how their own [oil-dependent] societies underperform and fail to win international respect.”Footnote 22

Recent studies add to the list of reforms that presumably enhance external legitimacy, from reforms focused on gender equalityFootnote 23 to waste management,Footnote 24 science,Footnote 25 and the environment.Footnote 26 Zumbrägel, for instance, argues that “green” reforms aim at “harnessing environmentalism to garner legitimation to please both national and international audiences.”Footnote 27 Gender equality reforms, such as electoral gender quotas, have long received attention in this light.Footnote 28 Bjarnegård and Zetterberg use the term “autocratic genderwashing” to describe when “women are placed in symbolic roles and high-ranking positions, gender-equality legislation is introduced, or women’s rights are strengthened—all so that an authoritarian regime can position itself as modern and progressive and thus enhance its international reputation.”Footnote 29 Benstead and Sari-Genc coin the term “gender diplomacy” to describe a similar phenomenon.Footnote 30

Unanswered Questions

However, despite significant theory backing the idea, empirical evidence demonstrating that authoritarian reforms actually do generate external legitimacy is limited. Only a handful of studies have sought to test the logic empirically, and some arrive at very different conclusions. For example, in their compelling observational analysis examining historical records of the stated views of the European Union, US State Department, and Amnesty International, Nielsen and Simmons find little to no evidence that governments, including authoritarian ones, gain public praise and recognition following their ratification of human rights treaties.Footnote 31 Yet Garriga, also using observational data, finds that participation in human rights regimes can have a “legitimating effect,” at least in terms of an improved reputation spurring greater inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI).Footnote 32

Several scholars focus on electoral gender quotas, and find evidence from survey experiments that this type of reform can also generate international reputational boosts. In two donor countries (United States and Sweden), Bush and Zetterberg asked respondents to evaluate hypothetical authoritarian regimes in terms of how democratic they are and how much aid (if any) should be given to them.Footnote 33 Although limited to electoral autocracies described as “developing,” the findings suggested that gender quotas can enhance support for aid, and that increasing the proportion of women in parliament can enhance both perceptions of democracy as well as support for aid. In a follow-up experiment, using a similar conjoint design, Bush, Donno, and Zetterberg find further evidence that reforms strengthening women’s rights bestow reputational benefits, though effects were notably weaker for electoral gender quotas compared to guarantees of equal economic treatment.Footnote 34 Finally, focusing on the UAE, Benstead and Sari-Genc find that depictions of a gender quota-balanced legislative body, compared to an all-male one, can promote positive US perceptions.Footnote 35

While these are all valuable contributions, cumulative knowledge remains elusive because studies use different methods and outcome variables, and also focus on different reforms and policy changes. All draw important distinctions between policy and actual practice as well, hinting at limits to any benefits that may arise. Several unanswered questions therefore remain, and this research aims to help address them.

Hypotheses

Q1: Do authoritarian reforms enhance external legitimacy?

The foundational hypothesis (H1) predicts that reforms do enhance external legitimacy for authoritarian regimes, providing a boon that can help explain why such regimes undertake them. Yet the conflicting empirical evidence raises the possibility that the foundational hypothesis may apply more narrowly than has been assumed. It is certainly not a foregone conclusion that reforms of many different types should imbue authoritarian regimes with greater legitimacy from the perspective of international audiences. Moreover, scholars often dismiss such reforms as mere “window dressing,” so broader international audiences may agree.

Why should authoritarian reforms enhance external legitimacy in the first place—what are the causal mechanisms? The prevailing arguments in the literature emphasize norms and social approval.Footnote 36 Just as deviating from international norms—defined as broadly accepted standards of appropriate behavior—is believed to generate disapproval, complying with norms should generate approval and support from international audiences.Footnote 37 To the extent that an authoritarian regime’s reforms signal steps toward heightened compliance with such norms, international audiences should be duly impressed. This dynamic should particularly apply to authoritarian regimes as “deviant actors” in a global normative environment favoring democracy. As Adler-Nissen observes in her discussion of (successful) stigma recognition, “the deviant state works to become normal and eventually succeeds in becoming accepted by international society.”Footnote 38

Of course, norms vary in concordance, institutionalization, and other respects, and there are multiple international audiences of note. Other mechanisms are also possible. While this research cannot address causal mechanisms directly, it can help establish whether a variety of reforms do appear to generate external legitimacy as predicted in the literature, consistent with proposed mechanisms.

Q2 What are the benefits that arise from increased legitimacy?

Although many studies argue that authoritarian regimes undertake reforms in part to gain external legitimacy, the substance of what is gained is not always clear, especially in light of legitimacy’s complexity as a concept. Empirically, what does it mean for an authoritarian regime to “gain legitimacy” as a result of its reforms? What intangible benefits accrue?

Theoretically, scholars emphasize both positive benefits associated with external legitimacy as well as shielding benefits. For example, in his study investigating the mechanisms of authoritarian image management, Dukalskis distinguishes efforts to “enhance or protect the legitimacy of the state’s political system for audiences outside its borders.”Footnote 39 The former are positive and promotional, ensuring that regimes can participate as full members of the international community, and also contributing to “soft power”—the ability to obtain preferred outcomes by attraction rather than coercion or payment.Footnote 40 The latter emphasize protection, that is, shielding from criticism and punitive action. This distinction is emphasized in many other studies of authoritarian reforms and external legitimacy as well.Footnote 41

A strong version of the foundational hypothesis predicts that reforms will enhance external legitimacy in both respects, generating both “positive” and “shielding” benefits. But it is likely that positive benefits will be stronger than shielding benefits (H2). Evidence suggests that people are more inclined to reward than to punish, and high audience costs can also arise when leaders back down on threats to carry out punitive actions.Footnote 42 Strategically, this would imply differing logics of gain—authoritarian regimes can more easily obtain positive benefits from their reforms than shield themselves from punitive actions.

Q3: Do legitimacy benefits depend on the perceived quality of the reforms, prevalence of critical assessments, and/or characteristics of the regime?

One important question raised by the literature is whether any legitimacy gains will hold in the face of critical information, especially information raising doubts about the regime’s commitment to reform. Nielsen and Simmons argue that practice not aligned with stated reforms will undermine any legitimacy gains.Footnote 43 In their experiments, Bush and Zetterberg find more consistent evidence for reputational boosts from actual practices flowing from reforms (a higher proportion of women in parliament) than reforms themselves (instituting an electoral gender quota).Footnote 44 Thus H3 predicts that legitimacy gains from reforms will diminish when critics’ reasons for skepticism are introduced.

Another contextual cue is the quality of the reforms themselves. Theories of technocracy emphasize how knowledge and expertise can imbue governments with greater legitimacy,Footnote 45 and many authoritarian reform efforts are assisted by high-profile teams of experts from think tanks and global consulting firms such as McKinsey and RAND.Footnote 46 Thus H4 predicts that the positive effects of reforms will increase when reforms are bolstered by technical expertise, and particularly so when the experts involved are described as American in the context of a US sample (H5).

Finally, existing research points to the possibility of ceiling effects. Authoritarian regimes already enjoying relatively high levels of external legitimacy may have less to gain from undertaking reforms. For example, Garriga finds that the positive effect of human rights treaty ratification on FDI inflows is especially strong in countries with weaker human rights records.Footnote 47 There may be similar ceiling effects in terms of the ability of reforms to generate legitimacy more broadly. Thus H6 predicts that the positive effects of reforms will be less pronounced for authoritarian regimes likely to be viewed more positively at baseline, such as those described as strong US allies and relatively liberal.

Q4: Are some types of reform more effective at generating external legitimacy than others?

Although there is scant theory about the relative weight by which differing reforms may enhance external legitimacy, the literature is arguably most robust, especially for Middle Eastern countries, with respect to reforms focused on gender equality.Footnote 48 Scholars theorize that regime elites have come to view this type of reform as “easier” to implement because it does not directly threaten regime stability. Yet for international audiences, the reform may still signal democratization, and also be associated with immediate, observable progress for women in contrast to the more diffuse dividends associated with institutional reforms. H7 therefore predicts that this type of reform will be most powerful, particularly in generating positive benefits.

Might higher-order categories of reform matter as well? One possible explanation for the conflicting empirical evidence is reform type. As noted, while some scholars found support for the idea that an inward-facing reform (supporting gender equality) generates reputational gains, others found very little evidence that an outward-facing reform (human rights treaty ratification) produced any such gains.Footnote 49 Here, inward-facing reforms are defined as those focused on progress at the domestic level, including the democratic (or “pseudodemocratic” reforms) featured in much of the early literature. Outward-facing reforms and policy changes are defined as those focusing on progress at the global level, including efforts to tackle climate change, reduce global poverty, and advance science and technology worldwide.

H8 predicts that inward-facing reforms will be associated with greater legitimacy gains, compared to outward-facing reforms, in terms of positive benefits. This aligns with a logic of countertype signaling whereby shifts that are surprising and “counter to type” (for example, authoritarian regimes becoming less authoritarian/more democratic) are especially impressive, perhaps because they are seen as costly and indicative of deeper norm compliance.Footnote 50 As mentioned earlier, several studies propose that authoritarian regimes face strong incentives in a democracy-dominated post–Cold War world to undertake reforms that make them appear more democratic, particularly to obtain positive benefits. The same strong incentives may be lacking for outward-facing reforms relating to globally oriented behavior.Footnote 51

Yet outward-facing reforms that stress global welfare benefits may still generate external legitimacy. H9 proposes that this type of reform will be associated with greater legitimacy gains, compared to inward-facing reforms, in terms of shielding benefits. According to this logic, international audiences will be less willing to approve punitive actions toward authoritarian regimes making outward-facing commitments to avoid jeopardizing the shared benefits that may arise (such as reduced global poverty, greater scientific collaboration, and more cooperative environmental agreements).

Research Design

To test hypotheses within the same methodological framework, three survey experiments were conducted iteratively over nationally representative samples of US respondents.Footnote 52 The United States setting is valuable because of the country’s significant global footprint and continued leadership role. Historically, it has acted as a major donor country and provider of security in many parts of the world, including the Middle East. Its overall stance toward a regime, reflected in diplomatic, military, and/or economic support, can influence that regime’s survival and overall trajectory.

National samples are also appropriate for several reasons. First, legitimacy implies widespread acceptance and support, not only elite endorsement, and evidence suggests that many authoritarian state leaders specifically target cross-border publics as well as policymakers.Footnote 53 In addition, although citizen perceptions are important in their own right, significant research demonstrates that public opinion matters for foreign policymaking, particularly through mechanisms of accountability and elite responsiveness.Footnote 54 It resonates not only in broad strokes, but also in key issue areas including foreign aid,Footnote 55 military action,Footnote 56 and economic sanctions.Footnote 57 In these dynamics, a government’s regime type and human rights record play key roles.Footnote 58 Effects on policy are more likely when citizens are informed,Footnote 59 and authoritarian regimes’ repressive behaviors—as well as their reforms—have often gained considerable news coverage, encouraging citizens to pay attention and re-evaluate.Footnote 60

Building on Bush and Zetterberg and Bush, Donno, and Zetterberg, all three experiments adopted the strategy of presenting respondents with a hypothetical authoritarian regime to evaluate, so that hypotheses about the theoretical conditions under which any legitimacy gains arise could be assessed.Footnote 61 They also extend those studies by testing a wider variety of reform types and assessing the role of contextual factors.

An iterative experimental approach was selected for several reasons. First, it enables researchers to plan a sequence of experiments with similar treatments and outcome measures, which facilitates drawing general conclusions and prioritizes replication.Footnote 62 This is important because prior studies have used different independent and dependent variables, making it difficult to draw general conclusions. It also allows an assessment of different reform types on the same outcome variable, again useful because prior studies have typically focused on one reform type.Footnote 63 In the case of the two conjoint experiments, it provides opportunities to assess the role of theoretically relevant contextual factors as well.Footnote 64

All hypothetical regimes were described as located in the Middle East. Theoretically, the region offers a fitting setting to test hypotheses. It is predominantly authoritarian, and eye-catching reforms are often underway. Many existing studies of reforms and legitimacy focus on this region, perhaps because of how unusually durable authoritarian governments there have proven to be.Footnote 65 Methodologically, this choice is also useful. Holding this region constant enables testing a variety of contextual factors in realistic ways, while minimizing the problem of impossible attribute combinations. The region has considerable variation in types of authoritarian regime, depth of autocracy, and strength of alliance relationships, all relevant factors for assessing if and when reforms enhance external legitimacy.

Finally, for all experiments, the key outcome is external legitimacy—a multifaceted concept that admittedly can be difficult to assess empirically. This research begins with a simple, first-cut indicator before operationalizing the concept in more complex ways. Thus Study 1 operationalizes legitimacy in terms of favorability toward the regime in question. While this is a rough measure, it is consistent with most operational definitions of legitimacy, which emphasize support or favorability as a minimum criterion.Footnote 66 As von Haldenwang observes, “Obviously, a legitimate political order should enjoy widespread support.”Footnote 67 Caspersen similarly notes that both internal and external legitimacy are commonly operationalized as “popular support for a regime.”Footnote 68 And as Ted Gurr wrote decades ago, despite the concept’s complexity, “most definitions associate legitimacy with supportive attitudes.”Footnote 69

In short, if reforms do enhance external legitimacy for authoritarian regimes, we would expect to see international audiences showing greater favorability toward those regimes. But support is not the only relevant indicator. Study 2 therefore operationalizes the concept in more complex ways that draw from theory; the main idea, discussed in more detail later, is that if regimes gain external legitimacy from their reforms, we should expect not only positive benefits (for example, favorability, support for greater trade relations) to accrue but also shielding benefits (for example, reluctance to support punitive actions).

Hypotheses developed in the prior section, organized by question and study, are depicted in Figure 1. To summarize, Study 1 focuses on whether authoritarian reforms enhance external legitimacy (Q1), though this foundational hypothesis is tested in all three studies for replication purposes. Study 2 focuses on Q2 concerning the benefits that arise from external legitimacy, as well as Q3 concerning whether these benefits depend on the perceived quality of the reforms, the prevalence of critical assessments, and/or regime characteristics. Study 3 focuses on Q4 probing the role of reform type.

Figure 1. Map of questions, hypotheses, and studies

Study 1

The first experiment was embedded in a large survey that explored critical issues facing the United States, and its focus was testing the foundational hypothesis (H1) with respect to a variety of reforms. The survey was administered online to a nationally representative US sample (n = 3,378) in 2021 (Appendix C). Respondents first read a brief paragraph about a hypothetical country:

Imagine a very conservative country in the Middle East. It has a modern airport, good hotels and restaurants, a striking natural landscape, and it welcomes tourists. Critics, however, emphasize that the country is not a democracy, lacks a free press, and denies civil liberties to many citizens. [final sentence]

For the final sentence, respondents were randomly assigned to one of six treatments featuring differing reforms underway—or a control group in which no reforms were underway (Figure 2). As the figure shows, various reforms were included, and chosen to prioritize external validity. All reforms described had actually occurred or were underway in one or more countries in the Middle East, allowing a useful test of the foundational hypothesis with respect to real reforms. Respondents rated their overall level of favorability toward the authoritarian regime on a feeling thermometer (from 0 = not favorable at all to 100 = very favorable).

Figure 2. Experimental conditions

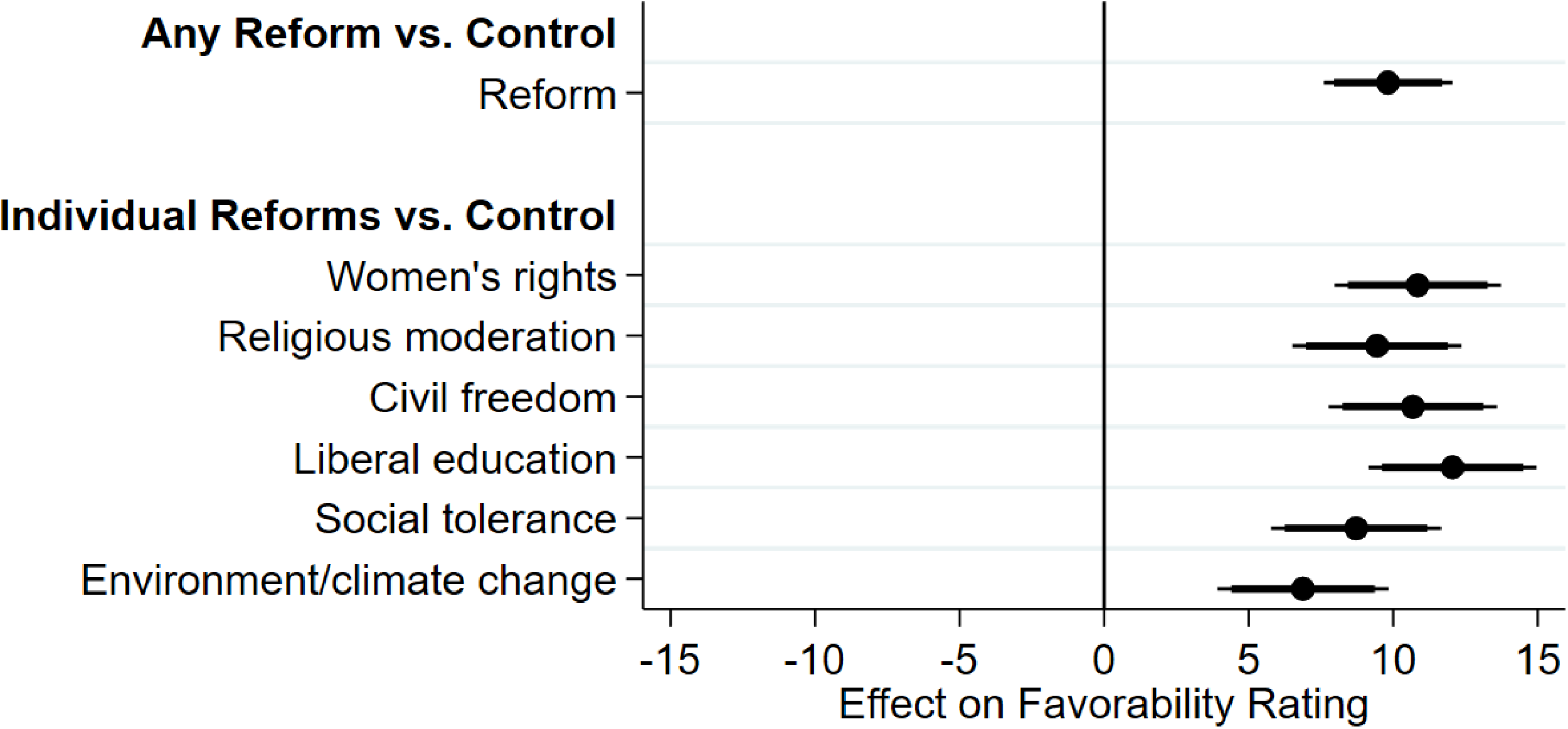

Results. The top panel in Figure 3 shows results from regressing the outcome variable on a dummy indicator for any reform (aggregating all reforms into a single “reform” treatment), with the “no reform” control group as baseline. The bottom panel shows results for the six individual treatment conditions.

As the figure shows, the foundational hypothesis received strong support. In the control group, mean favorability toward the authoritarian regime was 34.70, but when reforms were introduced, the average increase was almost ten percentage points (p = 0.000, Cohen’s d = 0.44). All reforms were individually associated with significantly greater favorability as well. These results suggest that many different reforms can generate external legitimacy for authoritarian regimes.

Study 2

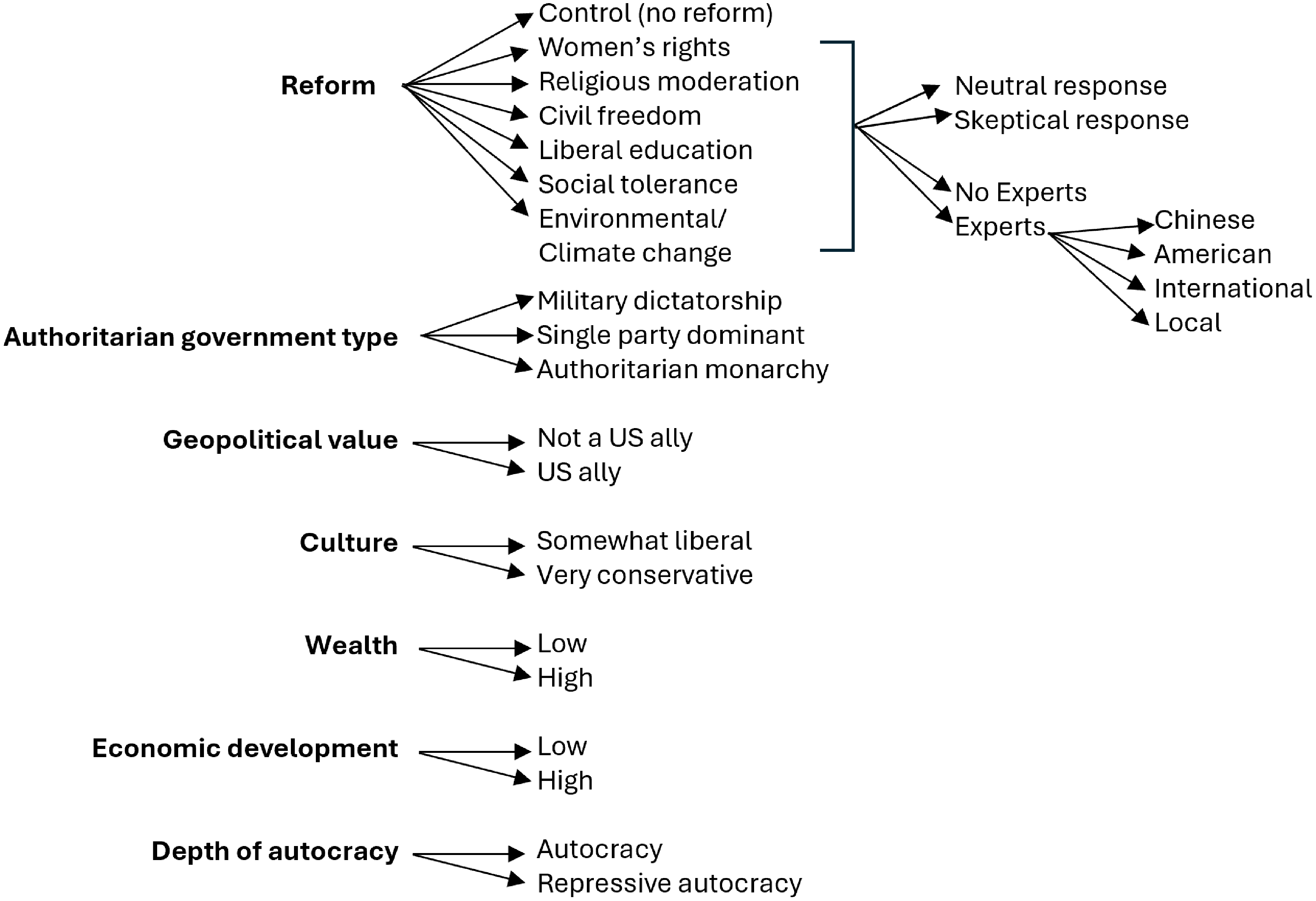

But Study 1 is, in some respects, an easy test. Few contextual cues were given, and none were varied. Thus Study 2, a conjoint experiment, extended Study 1 in several ways. A nationally representative sample of US respondents (n = 2,204) was invited to consider five hypothetical authoritarian regimes in the Middle East.Footnote 70 Conjoint experiments are distinguished by their multidimensional or factorial treatment format, along with the use of repeated measures.Footnote 71 In this study, a single-profile, vignette-based approach was used.

Each vignette described a particular reform that was underway (or a statement that no reforms were underway). For consistency, the reforms and their wording were the same as those used in Study 1. Figure 4 shows the conjoint design, with relevant background factors randomly varied including authoritarian regime type, depth of autocracy, wealth, culture, economic modernization, and geopolitical value to the United States.Footnote 72 These were selected because they are theorized to influence legitimacy in general, and also because they capture aspects of realistic variation in the Middle East. For example, modernization theory suggests that higher levels of wealth and economic development, and a relatively liberal as opposed to a very conservative culture, may help authoritarian regimes appear more “modern” and therefore commendable, especially to audiences in advanced liberal democracies.Footnote 73

Figure 4. Study 2 conjoint design

A government’s depth of autocracy (for example, how repressive it is) and geopolitical value to the United States (for example, whether it is an ally with a strong trade relationship) may influence external legitimacy as well.Footnote 74 Research suggests that US citizens strongly support cutting aid to repressive regimes, though they may also take into account the recipient’s geopolitical value, including how strategically or economically important the regime is to the United States.Footnote 75 Given that the region encompasses several different types of authoritarian regimes, regime type was also varied.Footnote 76

To test H3, for authoritarian regimes undergoing reform, the vignette mentioned either a skeptical response by observers, or a neutral one. Observers’ skepticism was attributed to “the country’s history and human rights record” to cast doubt on the regime’s commitment to reform. To test H4, whether the reform relied on expertise was varied, and if so, the nationality of the experts involved (H5). All levels of attributes were randomly assigned; see Appendix D for sample vignettes.

After each vignette, the survey captured both positive and shielding benefits, allowing an assessment of H2 as well as the robustness of the foundational hypothesis to a more complex operationalization of external legitimacy. Individual items were selected to match the theoretical literature; as discussed, the positive versus shielding distinction is emphasized in many studies relating to authoritarian reforms and external legitimacy.Footnote 77 Reforms are expected to promote a friendlier international environment in which the regime can participate fully and reap associated gains, such as gains from trade and investment—these are positive and participatory benefits. Reforms may also deflect criticism and calls for punitive action, potentially relieving external pressure to democratize or otherwise adjust policy; these are protective or shielding benefits.

Drawing from these insights, respondents were first asked to rate overall favorability toward the regime in general, followed by “stronger trade relations with this country, “cutting off diplomatic ties with this country,” and “participating in a boycott of products from this country” (1 = Very unfavorable to 7 = Very favorable). The first two items (overall favorability and support for trade relations) captured positive benefits, while the latter two (reluctance to cut relations and participate in a boycott) tapped shielding benefits.

Results. Figure 5 displays average marginal component effects (AMCEs), both for an aggregated “any reform” condition as well as for all individual reforms. AMCEs are computed from regressing the outcome variables on a series of indicator variables representing the attribute levels, with one omitted attribute serving as the base category and shown on the vertical reference line. Standard errors are clustered by respondent.

Figure 5. AMCEs plot showing 90% and 95% confidence intervals, with “no reform” condition as baseline; see Appendix D.5 for table

Figure 5 reveals strong support for the foundational hypothesis. As displayed in the top panel, when aggregating reforms into a single “any reform” treatment, overall favorability and support for trade increased, while support for cutting relations and boycotts decreased. Individual reforms generally showed the same pattern of results, with the partial exception of religious moderation. While this reform was associated with greater overall favorability, it had less impact on support for trade, and did not appear to shield regimes from punitive actions.

These results therefore replicate the main findings from Study 1.Footnote 78 They also extend those findings by suggesting that many reforms can generate not only positive benefits, but also shielding ones. In other words, respondents were more willing to reward regimes undertaking reforms—and also less willing to punish them.

Figure 5 also shows larger deviations from the “no reform” baseline for positive benefits (circles and squares) compared to deviations from the baseline for shielding benefits (triangles and diamonds), suggesting support for H2. The AMCE of the aggregated “any reform” condition on an index of positive benefits (mean of overall favorability and support for greater trade relations) is 0.25 (p = 0.000), while for shielding benefits (mean of cutting off relations, boycotting products), it is −0.11 (p = 0.008). A seemingly unrelated regression (SUR), where each equation represents a separate regression with the same predictors but different dependent variables, further supports H2; the cross-equation test of equality shows that reforms have a larger effect (in absolute value) on the index of positive benefits compared to the index of shielding benefits (diff = 0.13, SE = 0.06, p = 0.02).

For a fuller picture, Figure 6 displays AMCEs for all attributes, and shows that several background factors do influence aspects of legitimacy as would generally be expected. For example, regimes of greater geopolitical value were associated with higher overall favorability and support for trade, along with lower support for the two punitive actions. And regimes described as more repressive were associated with lower overall favorability and support for trade, compared to those not described as repressive, along with greater support for the two punitive actions.

Figure 6. AMCEs plot for all attributes showing 90% and 95% confidence intervals; see Appendix D.5 for table

To test H3, concerning critical information about the reform itself, Figure 7 limits the sample to regimes undergoing reform. As shown in the bottom left panel, H3 is supported. A skeptical response by observers to the reform, compared to a neutral response, dampens the legitimizing effects of reform, leading respondents to report lower overall favorability and support for trade, and higher support for cutting off relations and boycotts. However, such negative cues do not eliminate the gains entirely. Despite the reduced sample size, positive benefits persist when limiting to authoritarian regimes whose reforms prompt a skeptical response, relative to the no-reform baseline, though shielding benefits do not prove as resilient; see Appendix D.7.

Figure 7. AMCEs plots limiting to authoritarian regimes undergoing reform, showing 90% and 95% confidence intervals; see Appendix D.5 for table

The top left panel of Figure 7 also shows that the technocratic hypothesis (H4) was not supported. Interestingly, however, the diminished version (H5) received support in the case of positive benefits. Overall favorability and support for trade were significantly higher when limiting expert nationalities to American only (top right panel). This suggests that the legitimizing impact of expertise may be dependent on affinity with respect to the target audience. The results also revealed a strong delegitimizing effect for non-American experts (Appendix D.5).

Finally, are some regimes more likely to benefit than others? Is there evidence for ceiling effects consistent with H6? This hypothesis was partially supported. As shown in Appendix D.6, compared to the no reform condition, both US allies (high geopolitical value) and non-allies (low geopolitical value) undergoing reform gained legitimacy in terms of favorability, but only non-allies were associated with increased support for trade and decreased support for punitive actions. Non-allies were thus rewarded more, and the interaction terms (AMCE differences) are significant for both trade and boycott. Appendix D.6 provides details on all interactions involving geopolitical value and culture, and shows that even where interactions themselves are not significant, effects generally run in the hypothesized direction. By showing that regimes of high geopolitical value may gain less, perhaps because they already enjoy considerable external legitimacy, these results provide at least some evidence for ceiling effects consistent with H6.

Study 3

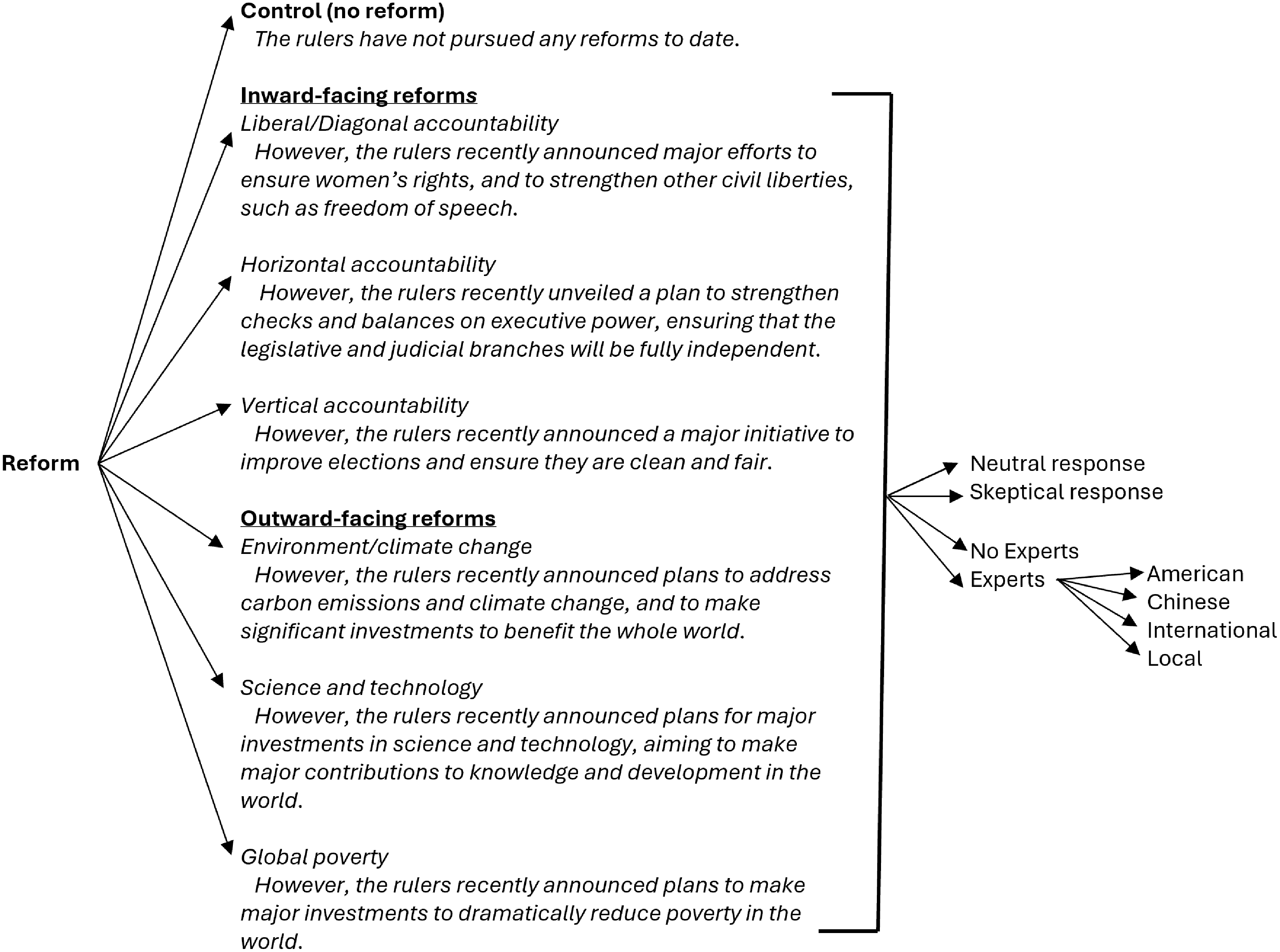

While Studies 1 and 2 prioritized external validity in the Middle East with respect to the reforms described, Study 3 aimed to replicate the main findings over theoretically driven types of reform applicable to any authoritarian regime. Thus Study 3 tested hypotheses about specific reforms as well as higher-order categories of reform.

Study 3 was conducted in July 2023, using a nationally representative US sample (n = 1,317).Footnote 79 To ensure alignment across studies, Study 3’s conjoint design was similar to Study 2 (Figure 4), with respondents presented with vignettes describing hypothetical Middle Eastern countries. All attributes and wording were the same except for the reforms themselves.

To test H8 and H9, the two main reform types were “inward-facing” and “outward-facing.” As shown in Figure 8, inward-facing reforms focused on domestic politics, and included three pro-democratic (or “pseudodemocratic”) reforms. Each one enhances democratic accountability along one of the three dimensions outlined by Lührmann, Marquardt, and Mechkova.Footnote 80 Thus one focuses on horizontal accountability (for example, checks and balances), another on vertical accountability (for example, elections), and the last on diagonal accountability (for example, civil liberties, including women’s rights and freedom of speech, allowing a test of H7). Outward-facing reforms focus on reforms and policy changes supporting progress at the global level, including efforts to tackle climate change, reduce global poverty, and advance science and technology for the world. See Appendix E.2 for a sample vignette.

Figure 8. Types of reform, Study 3

Study 3’s design also included a nonhypothetical country (Saudi Arabia) as the fifth country. In experiments, the use of a real country complements the use of hypothetical countries, especially in studies of reputation formation.Footnote 81 For example, it can combat “hypothetical bias,” and here it constitutes a harder test of the foundational hypothesis because respondents may already have strong attitudes about Saudi Arabia.Footnote 82

Respondents read the same structured vignette, with real values assigned to many attributes, including wealth (high), culture (very conservative), authoritarian government type (monarchy), economic development (high), and geopolitical value (high). Depth of autocracy was varied, given that the regime’s level of repressiveness does vary, and so were attributes associated with the reform itself (such as whether observers were neutral or skeptical, the use of expertise, and the nationality of any experts involved). Reform type was also varied, with minor changes in wording to align with real and/or planned reforms in the country; see Appendix E.4.Footnote 83

Results. Figure 9 displays average marginal component effects (AMCEs) for an aggregated “any reform” condition, compared to the “no reform” baseline condition, as well as for all individual reforms by reform type.Footnote 84 With few exceptions, Study 3 replicates the main findings from Studies 1 and 2—reforms generate external legitimacy for authoritarian regimes, both in terms of positive and shielding benefits, and positive benefits prove stronger than shielding benefits (Appendix G.3). Moreover, involving experts continues to have little effect, while negative information (a skeptical response, compared to a neutral one) continues to play a role but does not eliminate the gains (Appendix E.5).

Figure 9. AMCEs plot for Study 3 showing 90% and 95% confidence intervals, with “no reform” condition as baseline; see Appendix E.3 for table

Was the liberal reform strengthening women’s rights uniquely powerful? H7 received some striking support, at least for positive benefits. For overall favorability, a Wald test indicated that the effect of this reform was greater than the effect of all other reforms combined into an aggregate indicator (diff = 0.29, SE = 0.07, p = 0.000). This was also true for support for trade (diff = 0.14, SE = 0.06, p = 0.03). The hypothesis was not supported for shielding benefits, however.Footnote 85

H8 and H9 turn to higher-order categories of reform and their potentially different effects on dimensions of external legitimacy. H8 was supported. Taken together, the three inward-facing, pro-democratic reforms generated a significantly larger effect on legitimacy in terms of positive benefits, compared to the three outward-facing reforms. The former’s effect on the index of positive benefits was 0.56 (p = 0.000), while the latter’s effect on that index was 0.44 (p = 0.000). A Wald test indicated that this difference was significant (diff = 0.11, SE = 0.04, p = 0.01).

H9, however, was not supported—outward-facing reforms did not have a stronger effect on shielding benefits, compared to inward-facing reform. Outward-facing reforms, taken together, reduced willingness to endorse punitive actions (index of shielding benefits) by −0.20 (p = 0.002), while inward-facing reforms reduced willingness to endorse these actions by −0.25 (p = 0.000).Footnote 86

Finally, Figure 10 plots regression results for the task involving Saudi Arabia. As noted, the use of an actual authoritarian regime is unlikely to produce the exact same results. This is due to shifting salience and news coverage with respect to various reforms, as well as potentially stronger, less movable attitudes toward the country, especially one well known for its strict control over society. Yet as Figure 10 shows, the trends are similar, particularly for positive benefits which again prove more reliable. And once again, the most powerful reform was the liberal reform emphasizing citizens’ freedom and autonomy (which included women’s rights and freedom of speech). In this case, this reform proved more powerful than the rest both in terms of generating positive benefits for the Saudi government, as well as protecting it from punitive actions; see Appendix E.4.

Figure 10. Coefficient plot for fifth country in Study 3 (Saudi Arabia), showing 90% and 95% confidence intervals; see Appendix E.4 for table

Conclusion

In The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood’s classic dystopian novel, the United States is violently overthrown and replaced by the “Republic of Gilead,” a fanatical authoritarian regime that rapidly erases any semblance of democracy. Despite an implied awareness of its human rights abuses and totalitarian character, Gilead proceeds to build considerable external legitimacy, even admiration abroad, for its apparently effective reforms promoting a clean environment and high fertility rate within an atmosphere of global crisis. Arguments today about the effectiveness and therefore allure of authoritarian approaches to solving persistent problems such as climate change and corruption make Atwood’s tale all the more relevant.Footnote 87

Indeed, regarding the power of reform, Atwood’s tale is an extreme example of a dynamic the current research suggests is more than plausible. This research sought to determine if authoritarian regimes gain external legitimacy when they undertake reform. Using three survey experiments focusing on authoritarian regimes in the Middle East, results consistently suggest that they do gain such legitimacy, and that the gains are not unique to any particular reform. The results therefore strengthen and help integrate a variety of earlier arguments about the international incentives for authoritarian regimes to undertake different reforms—from democratic or “pseudodemocratic” institutional changes to green reforms.Footnote 88 While these arguments are individually persuasive, most focus on particular reforms, and this study contributes by testing their shared logic within a single framework.

The findings also add new knowledge about the benefits that arise from increased legitimacy, the comparative implications of different reform types, and the conditions under which regimes are more or less likely to reap those gains. Notably, the evidence suggests that reforms boost legitimacy in terms of positive benefits more so, and more reliably, than they boost legitimacy in terms of shielding benefits. This finding may help assuage those who worry that authoritarian regimes can use reforms in narrowly self-interested ways as a diversionary tactic to escape censure. But it also highlights the power of the positive, raising larger questions about the implications of such authoritarian “soft power” for the global normative environment.

Also striking from a global perspective is that inward-facing reforms proved more powerful than outward-facing reforms, suggesting greater incentives for domestic reforms and potentially less likelihood of reforms favoring international cooperation. The consistently powerful impact of one such inward-facing reform—liberal reforms enhancing women’s rights—is worth particular mention.Footnote 89 This type of reform has received considerable attention, especially with respect to authoritarian regimes in the Middle East, and the results here corroborate that special focus, while also generating new insights about it. For example, scholars have suggested that gender reforms are especially attractive to authoritarian regimes because they are relatively “easy” to implement domestically, without threatening deeper authoritarian power structures.Footnote 90 Yet another reason may be that such reforms really do stand above the fray in terms of their capacity to impress; thus, not only are the costs apparently low, but the benefits may be unusually high. How that calculus emerges and adapts, with respect to gender reforms but also other reforms, is a valuable topic for future research.

At the same time, the findings also highlight limits to the overarching logic. For example, authoritarian regimes of high geopolitical value (for example, US allies) appear to gain less, broadly consistent with a concept of “legitimacy ceiling effects.” Moreover, although many autocrats appear drawn to technocratic legitimacy formulas,Footnote 91 their use of expertise in undertaking reforms had little effect, except when the experts were described as American. By contrast, skeptical information about the reforms themselves that questioned the regime’s sincerity and drew attention to a history of human rights abuses did effectively reduce the gains, compared to a neutral response, though it did not completely eliminate them.

To what extent should we expect these findings to generalize beyond the United States, and beyond autocracies in the Middle East? While these are good questions for future research, there are reasons to believe the findings are broadly generalizable. Theoretically, the logic that reforms build external legitimacy for authoritarian regimes is not region or audience specific; it relies on the presence of international norms, which are by definition widely acknowledged. At the same time, some norms may be more powerful drivers of legitimacy from the perspective of certain audiences. For instance, it is likely that explicitly pro-democratic reforms will be most impressive to audiences in liberal democracies. But other reforms, such as those tackling climate change or promoting women’s empowerment, neither of which is necessarily linked to liberal democracy, could appeal more broadly.

It is also possible that reforms in Middle Eastern autocracies are especially powerful in the United States. Because of the region’s association with terrorism, the flow of oil, and gender inequality, and also a history of US entanglements, reforms emanating from authoritarian regimes in this region may gain greater news coverage, and be eagerly received by US audiences. Yet considerable variability is also likely, partly because geopolitical value matters as well and the region’s countries vary on that dimension. That said, it is worth noting that Bush, Donno, and Zetterberg found little effect of region (Africa, Asia, Middle East) when assessing the impact of gender equality reforms undertaken by authoritarian regimes, so at least that type of reform may attract significant attention regardless of where the authoritarian regime is located in terms of region.Footnote 92

Future research should investigate the mechanisms underlying these effects more directly,Footnote 93 and assess their durability. As Nielsen and Simmons suggest, it is possible that legitimacy gains are rather short-lived, and if so, the incentives for authoritarian regimes to undertake reforms, at least for the sake of external legitimacy, would be weaker.Footnote 94 In some respects, that would be a problematic outcome, particularly if there is widespread desire for authoritarian regimes to engage in these types of reform, however perfunctorily. Above all, in a world increasingly less dominated by democracies, future research should continue to study evolving international incentives for authoritarian regimes to undertake reforms, how those reforms shape their external legitimacy, and broader implications for the international normative environment.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this research note may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/H3UOKG>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this research note is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818325101197>.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research came from the University of Maryland, including the Critical Issues Poll directed by Shibley Telhami. For their specific comments and insights, I thank Shibley Telhami, Barbara Geddes, Michaelle Browers, and Patricia Wallace. I am also grateful for conference feedback after presentations of this work at the Middle East Studies Association (MESA) Annual Meeting in 2024 and the American Political Science Association (APSA) Annual Meeting in 2024. Finally, I thank the anonymous reviewers and editors of International Organization for their close attention and in-depth feedback.