During the past decades, substantial research has focused on the association between psychological distress and morbidity and mortality. Most studies have focused on the role of depression with coronary heart disease. Several meta-analyses indicate that depression is a risk factor for the development of coronary heart disease in the general population Reference Wulsin and Singal1-Reference Nicholson, Kuper and Hemingway3 and is associated with cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Reference Nicholson, Kuper and Hemingway3-Reference Meijer, Conradi, Bos, Thombs, van Melle and de Jonge6

Less research has focused on the role of anxiety. A recent meta-analysis showed that symptoms of anxiety were associated with a 26% increased risk of incident coronary heart disease. Reference Roest, Martens, de Jonge and Denollet7 Anxiety disorders have been associated with the development of coronary heart disease in younger men, Reference Janszky, Ahnve, Lundberg and Hemmingsson8 and with all-cause mortality in an older male population. Reference Van Hout, Beekman, de Beurs, Comijs, van Marwijk and de Haan9 The results for generalised anxiety disorder are inconsistent. Generalised anxiety disorder has been shown to be related to all-cause mortality in a veteran population. Reference Phillips, Batty, Gale, Deary, Osborn and MacIntyre10 However, in a community sample of older persons, generalised anxiety disorder did not increase the risk of death. Reference Holwerda, Schoevers, Dekker, Deeg, Jonker and Beekman11

In patients with acute myocardial infarction, the prevalence of elevated symptoms of anxiety is on average 30%. Reference Roest, Martens, Denollet and de Jonge12 In a meta-analysis including 12 studies covering 5750 patients with myocardial infarction, it was shown that anxiety was associated with a 36% increased risk of new cardiovascular events or mortality. Reference Roest, Martens, Denollet and de Jonge12 A significant limitation of the studies focusing on the relationship between anxiety and impaired prognosis in patients with myocardial infarction conducted thus far is that most have used questionnaires to assess the presence of elevated symptoms of anxiety. Although questionnaires can be used as screening tools, Reference Frasure-Smith and Lespérance13-Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams and Löwe16 they are not sufficient to diagnose an anxiety disorder. Furthermore, questionnaires are inadequate in distinguishing between emotional disorders, specifically between anxiety and depression. Reference Frasure-Smith and Lespérance13,Reference Balon17,Reference Beuke, Fischer and McDowall18 To our knowledge, only three studies have assessed the association between generalised anxiety disorder assessed with a diagnostic interview and adverse cardiovascular prognosis. Two of these studies were in patients with (stable) coronary heart disease and found significant associations between generalised anxiety disorder and cardiovascular events. Reference Frasure-Smith and Lespérance13,Reference Martens, de Jonge, Na, Cohen, Lett and Whooley19 In contrast, the third study concluded that acute coronary syndrome patients with a lifetime diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder tended to experience a better cardiac prognosis. Reference Parker, Owen, Brotchie and Hyett20

To date no study has assessed the prognostic impact of a diagnosis of current generalised anxiety disorder after acute myocardial infarction. Therefore, we evaluated the prognostic impact of generalised anxiety disorder after myocardial infarction on new cardiovascular events and mortality up until 10 years after the myocardial infarction using a formal diagnostic interview. As generalised anxiety disorder and depression are closely associated, Reference Krueger21-Reference Lamers, van Oppen, Comijs, Smit, Spinhoven and van Balkom23 we specifically analysed whether its impact is independent from depression.

Method

Patients

Patients were included from the Depression after Myocardial Infarction (DepreMI) study. This was a naturalistic cohort study evaluating the effects of depression after myocardial infarction on adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Details of this study are described elsewhere. Reference Spijkerman, de Jonge, van den Brink, Jansen, May and Crijns24,Reference Spijkerman, van den Brink, Jansen, Crijns and Ormel25 Previous publications on DepreMI have all focused on the association between depression and cardiac disease. Reference Spijkerman, de Jonge, van den Brink, Jansen, May and Crijns24-Reference de Jonge, van den Brink, Spijkerman and Ormel28 These studies found a significant association between depressive symptoms and incident depressive episodes with cardiovascular events after a 2.5-year follow-up period. Reference Spijkerman, van den Brink, May, Winter, van Melle and de Jonge26-Reference de Jonge, van den Brink, Spijkerman and Ormel28 The impact of anxiety on cardiovascular outcomes has not been examined before. Eligible patients admitted consecutively for myocardial infarction at four hospitals in The Netherlands between September 1997 and September 2000 were asked to participate. At least two of the following three criteria for myocardial infarction had to be met: (1) a documented increase in cardiac enzyme levels; (2) typical electrocardiographic changes; and (3) at least 20 min of chest pain. Exclusion criteria were the presence of another somatic disease likely to influence short-term survival, myocardial infarction during hospital admission for another reason (except unstable angina), and being unable to participate in study procedures. The institutional review board of each participating hospital approved the protocol and all participants signed informed consent.

Assessment of generalised anxiety disorder

Generalised anxiety disorder is characterised by a period of at least 6 months with prominent tension, worry and feelings of apprehension about everyday events and problems. Associated symptoms are of autonomic arousal and other somatic or cognitive symptoms of tension and worry. 29 The presence of an ICD-10 diagnosis of current generalised anxiety disorder was assessed by means of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version 1.1, Reference Wittchen30 which was administered 3 months post-myocardial infarction in order to reduce possible confounding in the period immediately after the myocardial infarction.

Assessment of the covariates

Age, gender, clinical characteristics, cardiac risk factors and comorbidities were assessed during hospitalisation for the index myocardial infarction and from hospital charts. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was assessed by echocardiography, radionuclide ventriculography, gated single photon emission computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, angiography or clinical assessment. Living alone and level of education were assessed in an interview 3 months after the myocardial infarction. The presence of an ICD-10 diagnosis of a post-myocardial infarction depressive episode was assessed with the CIDI at 3 months after the myocardial infarction.

Assessment of adverse outcomes

Data concerning mortality were obtained up until 31 December 2007 from the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics by linkage to the municipal personal records database. Data concerning hospital admissions in the period between the index myocardial infarction and 31 December 2007 came from the Dutch national registry of hospital discharges and were obtained from the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics by linkage to the municipal personal records database. Hospital readmissions with ICD-9 codes 410, 411, 413, 414 (ischemic heart disease); 427.1, 427.4, 427.5 (cardiac arrhythmia); 428, 398.91, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.11, 404.13, 404.91, 404.93 (heart failure); 433, 434, 435, 437.0, 437.1 (cerebrovascular disease); and 440, 443.9 (peripheral vascular disease) were included as cardiovascular events. We included these events to be consistent with previous publications on this cohort. Reference Spijkerman, van den Brink, May, Winter, van Melle and de Jonge26-Reference de Jonge, van den Brink, Spijkerman and Ormel28 The primary end-point of this study was a combined end-point of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality. The follow-up period for adverse outcomes started at the CIDI interview at 3 months after the myocardial infarction and ended on 31 December 2007. This time frame was chosen to optimise the number of potential events. Only deaths and cardiovascular-related readmissions occurring between the CIDI interview at 3 months after the myocardial infarction and 31 December 2007 were considered as adverse outcomes.

Statistical analyses

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were compared with chi-squared and Student's t-test. For this purpose, nonnormally distributed continuous variables were log-transformed. We calculated event-free survival time as time to first event or death. If no event or death occurred, the patient was censored at 31 December 2007. Using Cox regression we evaluated whether event-free survival was different for patients with and patients without generalised anxiety disorder after the myocardial infarction. In the basic model, adjustments were made for age and gender. Additionally, we adjusted for LVEF and diagnosis of post-myocardial infarction depression, because these have been shown to be associated with worse cardiovascular prognosis. In sensitivity analyses, adjustments were made for other clinical variables that significantly predicted cardiovascular events and mortality in the present sample, namely anterior site of the index myocardial infarction, and history of myocardial infarction and peripheral vascular disease. For all analyses, SPSS 14 for Windows was used and significance level was set at 0.05, two-tailed.

Results

For this study, 1166 patients were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 882 patients were eligible, of whom 528 (59.9%) signed an informed consent. Of the 461 patients with a CIDI interview, 23 were excluded owing to missing information at the end-point, leaving 438 patients included for further analyses.

Generalised anxiety disorder

Three months after the index myocardial infarction, 24 patients (5.5%) met the criteria for generalised anxiety disorder. Patients with generalised anxiety disorder were less likely to be treated with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (P = 0.03) and more likely to have a history of myocardial infarction (P = 0.02) compared with patients without generalised anxiety disorder. Of the patients with generalised anxiety disorder, 12 (50%) had a concurrent depressive episode (Table 1).

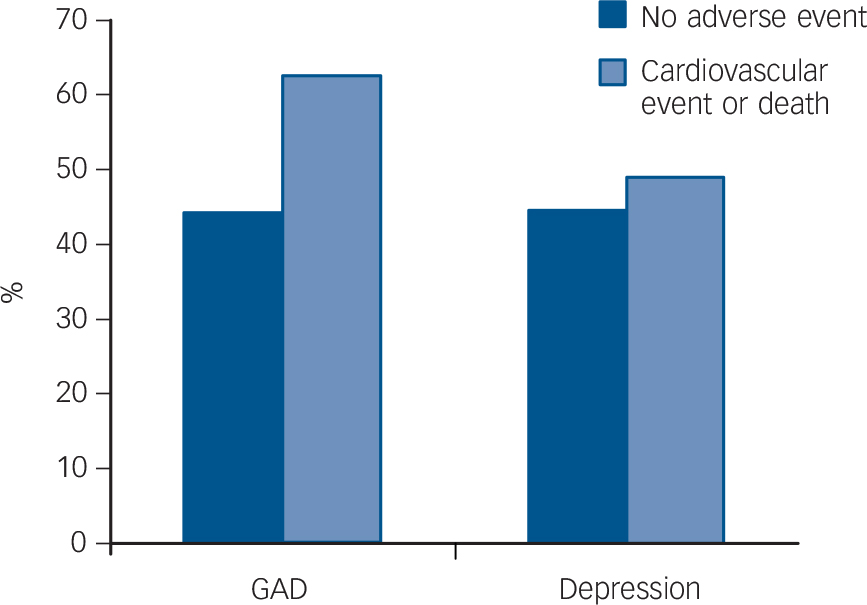

During follow-up, 15 patients (62.5%) with generalised anxiety disorder had a cardiovascular event or died compared with 183 patients (44.2%) without generalised anxiety disorder (Fig. 1).

Predictors of cardiovascular events and mortality

During the follow-up period, 198 patients met the combined end-point of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events with a mean (standard deviation) follow-up period of 5.7 (3.1) years. Patients who had an event during the follow-up period were more likely to be older (P<0.001), living alone (P = 0.04), to have an anterior myocardial infarction (P = 0.02), a LVEF lower than 40 (P<0.001), and a history of myocardial infarction (P = 0.001), cerebrovascular disease (P = 0.01) and peripheral vascular disease (P<0.001) (Table 2).

Generalised anxiety disorder as a predictor of cardiovascular events and mortality

Table 3 shows the association of generalised anxiety disorder with adverse prognosis for different models. Generalised anxiety disorder was associated with cardiovascular events and mortality after adjustment for age and gender (Fig. 2).

After additional adjustment for LVEF, generalised anxiety disorder remained an independent predictor of adverse outcome. Left ventricular ejection fraction (hazard ratio (HR) 1.58, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.17-2.14; P = 0.003) and age (HR per year 1.03, 95% CI 1.02-1.04, P<0.001) were also significant predictors in this model. Adjustment for post-myocardial infarction depression did not affect the association between generalised anxiety disorder and cardiovascular events and mortality. Post-myocardial infarction depression was not a

TABLE 1 Comparison of patients with and without generalised anxiety disorder a

| No generalised anxiety disorder (n = 414) | Generalised anxiety disorder (n = 24) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 60.7 (11.4) | 58.3 (10.9) | 0.33 |

| Male, n (%) | 334 (80.7) | 20 (83.3) | 0.75 |

| Primary school only, n (%) | 78 (18.8) | 6 (25.0) | 0.46 |

| Living alone, n (%) | 58 (14.0) | 5 (20.8) | 0.35 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 194 (51.3) | 14 (63.6) | 0.26 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction <40, n (%) | 97 (23.5) | 7 (29.2) | 0.53 |

| Anterior site of myocardial infarction, n (%) | 130 (31.4) | 8 (33.3) | 0.84 |

| Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, n (%) | 100 (26.3) | 1 (4.8) | 0.03 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft, n (%) | 12 (3.2) | 2 (9.5) | 0.12 |

| Killip class ≥2, n (%) | 13 (3.2) | 2 (8.3) | 0.18 |

| Creatinine phosphokinase-MB, b mean (s.d.) | 117.8 (122.9) | 121.7 (182.2) | 0.16 |

| Creatinine phosphokinase, b mean (s.d.) | 1322.8 (1319.2) | 1818.9 (3010.8) | 0.48 |

| History of myocardial infarction, n (%) | 53 (12.8) | 7 (29.2) | 0.02 |

| History of cerebral vascular disease, n (%) | 18 (4.3) | 1 (4.2) | 0.97 |

| History of peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 27 (6.5) | 3 (12.5) | 0.26 |

| Family history of cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 155 (37.4) | 9 (37.5) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 37 (8.9) | 4 (16.7) | 0.21 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 118 (28.5) | 3 (12.5) | 0.09 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia, n (%) | 144 (34.8) | 7 (29.2) | 0.57 |

| Body mass index, mean (s.d.) | 26.7 (4.0) | 26.8 (4.1) | 0.92 |

a t-test for continuous variables and chi-squared for dichotomous variables were used.

b Log-transformations of creatinine phosphokinase were used for the t-test.

significant predictor of adverse outcome in this model (HR = 1.20, 95% CI 0.80-1.80; P = 0.38).

In sensitivity analyses, in addition to age and gender, consecutive adjustment for history of myocardial infarction, history of peripheral vascular disease, and anterior site of the index myocardial infarction did not materially affect the association between generalised anxiety disorder and adverse prognosis (Table 3).

Discussion

This study is the first to assess the prognostic impact of a diagnosis of current generalised anxiety disorder following myocardial infarction on cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality up until 10 years after the myocardial infarction. Patients with generalised anxiety disorder were at an almost twofold increased

Fig. 1 Percentage of cardiac events and all-cause mortality in patients with v. without generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) and patients with v. without depression.

risk of adverse prognosis after adjustment for age, gender and several cardiac disease severity parameters. Our findings are in concordance with those of other studies that investigated the impact of generalised anxiety disorder in patients with stable heart disease. Reference Frasure-Smith and Lespérance13,Reference Martens, de Jonge, Na, Cohen, Lett and Whooley19 In the present study, adjustment for depression did not influence the association of generalised anxiety disorder with adverse prognosis. This is consistent with other studies assessing the association between anxiety and cardiovascular events independent from depression. Reference Martens, de Jonge, Na, Cohen, Lett and Whooley19,Reference Strik, Denollet, Lousberg and Honig31

Potential mechanisms

Several potential biological mechanisms might explain the association between generalised anxiety disorder and coronary heart disease. For instance, several studies found a relationship

Fig. 2 The association of generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) after myocardial infarction with cardiac events and all-cause mortality adjusted for age and gender.

TABLE 2 Comparison of patients with and without an adverse prognosis a

| Total sample (n = 438) | Event-free (n = 240) | Adverse event (n = 198) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 61 (11.4) | 58 (10.8) | 63 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 354 (80.8) | 198 (82.5) | 156 (78.8) | 0.33 |

| Primary school only, n (%) | 84 (19.2) | 42 (17.5) | 42 (21.2) | 0.33 |

| Living alone, n (%) | 63 (14.4) | 27 (11.3) | 36 (18.2) | 0.04 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 208 (52.0) | 114 (51.1) | 94 (53.1) | 0.69 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction <40, n (%) | 104 (23.8) | 40 (16.7) | 64 (32.5) | <0.001 |

| Anterior site of myocardial infarction, n (%) | 138 (31.5) | 64 (26.7) | 74 (37.4) | 0.02 |

| Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, n (%) | 101 (25.2) | 61 (27.4) | 40 (22.5) | 0.26 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft, n (%) | 14 (3.5) | 10 (4.5) | 4 (2.2) | 0.23 |

| Killip class 2, n (%) | 15 (3.4) | 6 (2.5) | 9 (4.6) | 0.24 |

| Creatinine phosphokinase-MB, b mean (s.d.) | 118.0 (126.6) | 117.9 (132.0) | 118.1 (119.9) | 0.75 |

| Creatinine phosphokinase, b mean (s.d.) | 1350.0 (1461.0) | 1347.2 (1523.8) | 1353.3 (1384.9) | 0.70 |

| History of myocardial infarction, n (%) | 60 (13.7) | 21 (8.8) | 39 (19.7) | 0.001 |

| History of cerebral vascular disease, n (%) | 19 (4.3) | 5 (2.1) | 14 (7.1) | 0.01 |

| History of peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 30 (6.8) | 7 (2.9) | 23 (11.6) | <0.001 |

| Family history of cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 164 (37.4) | 89 (37.1) | 75 (37.9) | 0.86 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 41 (9.4) | 18 (7.5) | 23 (11.6) | 0.14 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 121 (27.6) | 66 (27.5) | 55 (27.8) | 0.95 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia, n (%) | 151 (34.5) | 80 (33.3) | 71 (35.9) | 0.58 |

| Body mass index, mean (s.d.) | 26.7 (4.0) | 26.7 (4.5) | 26.7 (3.3) | 0.98 |

| Depression, n (%) | 65 (14.8) | 33 (13.8) | 32 (16.2) | 0.48 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder, n (%) | 24 (5.5) | 9 (3.8) | 15 (7.6) | 0.08 |

a t-test for continuous variables and chi-squared for dichotomous variables were used.

b Log-transformations of creatinine phosphokinase were used for the t-test.

between anxiety and indicators of autonomic dysfunction in patients with myocardial infarction, including reduced heart variability Reference Martens, Nyklícek, Szsabó and Kupper32 and reduced baroflex cardiac control. Reference Watkins, Blumenthal and Carney33 Anxiety is also associated with increased platelet activity Reference Cameron, Smith, Lee, Hollingsworth, Hill and Curtis34 and markers of inflammation Reference Pitsavos, Panagiotakos, Papageorgiou, Tsetsekou, Soldatos and Stefanadis35 in otherwise healthy individuals. Another mechanism that may explain the association between anxiety and coronary heart disease is unhealthy behaviour, such as physical inactivity, an unhealthy diet and smoking. Anxiety is related to an unhealthy lifestyle in individuals at risk of coronary heart disease. Reference Bonnet, Irving, Terra, Nony, Berthezène and Moulin36 In addition, anxiety following myocardial infarction is associated with lower adherence to various riskreducing recommendations such as smoking cessation. Reference Benninghoven, Kaduk, Wiegand, Specht, Kunzendorf and Jantschek37,Reference Kuhl, Fauerbach, Bush and Ziegelstein38 However, in a recent study, a variety of potential mediating mechanisms, including levels of cortisol and noradrenaline, heart rate variability, inflammation, smoking, medication nonadherence, and physical inactivity, could not explain the association between generalised anxiety disorder and cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary heart disease. Reference Martens, de Jonge, Na, Cohen, Lett and Whooley19 More research is needed to identify the mechanisms through which generalised anxiety disorder leads to an adverse prognosis.

TABLE 3 Association of generalised anxiety disorder with cardiac events and all-cause mortality

| Controlling for | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Age, gender | 1.94 (1.14–3.30) | 0.01 |

| Age, gender, left ventricular ejection fraction | 1.92 (1.13–3.28) | 0.02 |

| Age, gender, depression | 1.84 (1.06–3.17) | 0.03 |

| Age, gender, history of myocardial infarction | 1.81 (1.06–3.09) | 0.03 |

| Age, gender, history of peripheral vascular disease | 1.95 (1.15–3.31) | 0.01 |

| Age, gender, anterior site of index myocardial infarction | 1.89 (1.11–3.22) | 0.02 |

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the present study is the use of a standardised diagnostic interview to assess the presence of generalised anxiety disorder in this sample of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Other strengths are the long follow-up period and the objective and comprehensive assessment of cardiovascularrelated readmissions and mortality, resulting in a sufficient number of events. Limitations of this study are that we did not have information on the duration of the current generalised anxiety disorder period or information on whether patients were treated for generalised anxiety disorder or depression. In addition, we could not take the possible development of new generalised anxiety disorder or depressive episodes during the time frame of the follow-up period into account. Another limitation is the relatively small sample size, which limits our ability to adjust for potential covariates simultaneously. As a result of the relatively small sample size, we could not assess the impact of the comorbidity of generalised anxiety disorder and depression. It has been suggested that generalised anxiety disorder and depression might interact synergistically to affect cardiovascular mortality. Reference Phillips, Batty, Gale, Deary, Osborn and MacIntyre10 However, in a study in patients with stable coronary heart disease, those with comorbid depression and generalised anxiety disorder were not at a greater risk of cardiovascular events compared with people with coronary heart disease with only depression or generalised anxiety disorder. Reference Frasure-Smith and Lespérance13 Further, another large population study found that comorbid anxiety symptoms reduced mortality compared with depressive symptoms alone. Reference Mykletun, Bjerkeset, Øverland, Prince, Dewey and Stewart39 Therefore, more research on the impact of comorbid anxiety and depression on the development and progression of coronary heart disease is warranted.

In our study, the association between generalised anxiety disorder and adverse prognosis could not be explained by several cardiac disease severity parameters, including LVEF and anterior site of the index myocardial infarction. However, it is still possible that the association is confounded by disease severity, especially since some symptoms of generalised anxiety disorder, such as palpitations and chest pain, might also be symptoms of heart disease. Further, patients with generalised anxiety disorder might worry about their health and be more likely to consult their doctor and be admitted to the hospital with cardiac complaints. This might explain part of the association between generalised anxiety disorder and cardiovascular-related hospital readmissions. To minimise this effect, we excluded hospital admissions for chest pain only from our analyses. Furthermore, although analyses on mortality separate from cardiovascular events were underpowered, the hazard ratio suggested an adverse effect of generalised anxiety disorder on mortality alone as well (data not shown).

Clinical implications

Although it has not been specifically studied in patients with heart disease, generalised anxiety disorder can be effectively treated with psychopharmacological treatment, for example selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, and cognitive-behavioural therapy. Reference Davidson40 Unfortunately, many patients do not receive adequate treatment. Reference Davidson40 Besides the impact of anxiety on disability and decreased quality of life, clinicians should be aware of the finding that generalised anxiety disorder is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality following myocardial infarction.

Funding

The DepreMI study was funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (Zon MW, grant ). P.J. and M.Z. are supported by a VIDI grant from the Dutch Medical Research Council (grant ).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.