Introduction

Greece has a particular pride of place in the history of Mediterranean survey. It was home to a foundational project in the form of the University of Minnesota Messenia Expedition (UMME; McDonald and Rapp Reference McDonald and Rapp1972), it was a hotbed for the incubation of intensive survey techniques that became mainstream around the Mediterranean between the 1970s and 1990s, and it has a very high number of systematic archaeological survey projects per square kilometre in comparison with other parts of the Mediterranean. There is also a long history of summarizing and reflecting on the practice of archaeological survey in Greece (e.g. Cherry Reference Cherry, Keller and Rupp1983; Reference Cherry and Kardulias1994; Bennet and Galaty Reference Bennet and Galaty1997; Tartaron Reference Tartaron2007; Bintliff Reference Bintliff2018; Knodell and Leppard Reference Knodell and Leppard2018; Attema et al. Reference Attema, Bintliff, Van Leusen, Bes, De Haas, Donev, Jongman, Kaptijn, Mayoral, Menchelli, Pasquinucci, Rosen, García Sánchez, Gutierrez Soler, Stone, Tol, Vermeulen and Vionis2020; Knodell et al. Reference Knodell, Wilkinson, Leppard and Orengo2023).

Early archaeological surveys had roots in topographic traditions, which gave way to multi-disciplinary, systematic investigations of regions in the mid-twentieth century. A ‘new wave’ of increasingly intensive surveys in the 1980s and 1990s saw the development of systematic methods of side-by-side fieldwalking in order to map the distribution of artifacts across the landscape and pay attention to ‘off-site’ traces of human activity, alongside the identification and mapping of archaeological sites (Bintliff Reference Bintliff, Doukellis and Mendoni1994; Cherry Reference Cherry and Kardulias1994). Over the last 25 years, surveys have benefited tremendously from advancements in remote sensing, database technologies, and geographic information systems (GIS), which have allowed regional archaeologists to carry out more detailed analyses and ask new questions of archaeological landscapes. Survey and landscape archaeology today comprise a diverse range of practices including fieldwalking, gridded collection at archaeological sites, architectural mapping, and geophysical survey, among other things (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Survey-based fieldwork in Greece: (a) fieldwalking with the Western Argolid Research Project (courtesy of Dimitri Nakassis); (b) architectural mapping with the Small Cycladic Islands Project; (c) gridded collection on Kato Kouphonisi with the Keros-Naxos Seaways Project (courtesy of Michael Boyd); (d) finds sorting during gridded collection with the Bays of East Attica Regional Survey (courtesy of Sarah Murray).

This article reviews the work of archaeological survey projects in Greece over the last 25 years, with particular emphasis on the last 10 years. Archaeological surveys typically focus on the documentation of material culture through surface remains. In Greece, surveys were long defined in contrast to excavations, though this strict permitting distinction is no longer in place. Collection practices and particular methods are now regulated according to the terms of individual permits. The size of project areas has been limited to 30km2 since 2002. Many projects have larger study areas, but the limit applies to areas of active investigation with artifact collection or formal documentation. Under this broad umbrella for what constitutes a ‘survey’ we can identify three main types of projects, according to scale and context: (1) regional or landscape surveys, which may vary in methods, scale, and intensity; (2) site surveys focused on a particular site and (possibly) its immediate surroundings, via artifact collection, architectural documentation, and/or geophysical survey; and (3) underwater surveys. This article focuses on the first category, although some site surveys will be discussed as well, not least because site documentation is also an important part of many larger-scale surveys. I do not discuss underwater surveys here (see Briggs and Campbell Reference Briggs and Campbell2023 for a recent review), nor do I systematically review geophysical surveys (see Donati and Sarris Reference Donati and Sarris2016).

Even this first category of regional or landscape surveys is extremely broad in terms of the methods and goals of projects that fall within it. Some focus on the identification and documentation of sites; others focus on mapping artifact distributions across the landscape. The former are often termed ‘extensive’ or ‘reconnaissance’ surveys, while the latter are usually called ‘intensive’ surveys, although these terms may be deployed by different projects to mean different things. In terms of territorial remit, project areas vary dramatically, with early extensive surveys covering thousands of square kilometres, while site surveys (and even some projects that claim to be regional surveys) may cover only a few hectares or less. Some aim to investigate a region for its own sake, while others aim to better contextualize a single site. Some projects focus on a particular period, while others are diachronic in scope. Even this distinction is not so simple, since ‘diachronic’ projects are usually (but not always) only diachronic within the scope of pottery-producing societies of the Holocene.

In addition to the types of projects above (and most of the projects discussed below), most of which can be characterized as academic research projects, a tremendous amount of survey work is carried out by the Greek Archaeological Service in the form of rescue or assessment projects for various types of construction, site registers, and more. Short reports are published in Archaiologikon Deltion, and elsewhere, but much information is relegated to a grey literature of internal reports. A recent development (since 2020) is the online publication of the Archaeological Cadastre of Greece, which contains descriptions and geospatial data for over 17,000 monuments, ca. 3,400 archaeological and historical sites, 844 protected areas, and 220 museums (https://www.arxaiologikoktimatologio.gov.gr/en ). While it would be impossible to review these types of surveys systematically, they must be mentioned as widespread and significant archaeological work, reporting on which may be consulted in collaboration with local ephorates.

I begin with a summary of recent publications (a selective sample from the last 10 years) of synthetic or thematic relevance. The bulk of this article describes recent survey-based fieldwork throughout Greece. At the end, I reflect on some broad trends and issues that merit further consideration. I argue that, on the one hand, there has never been more data available or as powerful a toolkit for investigating archaeological landscapes; on the other, concerns with methodology and ever-higher data resolution have at times obscured regional-scale research questions of broader significance.

Recent publications of broad geographical or thematic relevance

Two recent syntheses of survey practices in the Mediterranean deserve special mention. Attema et al. (Reference Attema, Bintliff, Van Leusen, Bes, De Haas, Donev, Jongman, Kaptijn, Mayoral, Menchelli, Pasquinucci, Rosen, García Sánchez, Gutierrez Soler, Stone, Tol, Vermeulen and Vionis2020) provide an overview of survey methods in Mediterranean archaeology in the form of a ‘guide to good practice’. The article is largely the product of the Mediterranean Survey Workshop, which has convened twice per year since 2000. Another recent paper systematically collected data about surveys across the Mediterranean, describing several schools of thought and practice and a wide range of goals, methodologies, and ‘types’ of project (Knodell et al. Reference Knodell, Wilkinson, Leppard and Orengo2023).

The Journal of Greek Archaeology (JGA) and Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology (JMA) regularly publish papers on archaeological surveys in Greece (at a rate much higher than other journals relevant to Greek archaeology). Recent special sections in JGA address several relevant themes: the medieval countryside in the Aegean and Anatolia (Athanassopoulos Reference Athanassopoulos2020); GIS in archaeology (Evangelidis et al. Reference Evangelidis, Tsiafaki, Mourthos and Karta2024); and new applications of lidar analysis in landscape archaeology in Greece (Knodell Reference Knodell2025a). A JMA paper by Meyer (Reference Meyer2022) critiques the widely deployed ‘siteless’ model of intensive surveys, arguing for renewed attention to site definition and quantification; this set off a debate about priorities and potential in research design and interpretation (de Haas et al. Reference de Haas, Leppard, Waagen and Wilkinson2023; Meyer Reference Meyer2023). In a 2012 editorial, JMA noted that survey archaeology was the largest category of papers published by the journal (Knapp, Cherry and van Dommelen Reference Knapp, Cherry and van Dommelen2012). More recently, Given (Reference Given and Manning2022) observed a decline in the number of survey papers published (up to 2019), both in JMA and in a review of 15 journals related to Mediterranean archaeology, following a peak in 2007. However, in articles from 2019 to 2024, JMA has published about one-third of its articles either about survey or regional analyses (J. Cherry pers. comm.).

Several recent papers and edited volumes consider the interpretation of survey assemblages. An edited volume on the recording and interpretation of survey ceramics has taken on issues of collection strategy, diagnosticity, and the representativeness of survey finds (Meens, Nazou and van de Put Reference Meens, Nazou and van de Put2023). Bintliff (Reference Bintliff2023) synthesizes long-running debates concerning the creation of ‘haloes’ through manuring around habitation areas as evidence for agricultural intensification, highlighting the importance of ‘off-site’ assemblages. A recent review of soil geochemistry applications in archaeology demonstrates the relevance of another type of data to address questions of human impact at and around habitation areas (Bintliff and Degryse Reference Bintliff and Degryse2022). Other important works include survey-based contributions to themes of political geography in the Bronze Age (van Wijngaarden and Driessen Reference Van Wijngaarden and Driessen2022), Roman urbanism (de Ligt and Bintliff Reference de Ligt and Bintliff2020), and imperialism (Düring and Stek Reference Düring and Stek2018), and social complexity in several periods (Knodell and Leppard Reference Knodell and Leppard2018).

New work on rurality has formed an important complement to urbanism, especially in considering the evidence of ‘the ancient Greek farmstead’ from multiple regions (McHugh Reference McHugh2017), rural communities in the Byzantine world (Kondyli Reference Kondyli2022), and the broader importance of rural landscapes (and their dynamics) in Archaic Cyprus (Kearns Reference Kearns2023). Other studies have examined the importance of particular types of landscapes that are often considered marginal, evaluating land use and habitation practices in small islands across Greece (Knodell Reference Knodell2025b) and in mountainous environments in Crete (Kalantzopoulou Reference Kalantzopoulou2022; Reference Kalantzopoulou2023; Papadatos and Kalantzopoulou Reference Papadatos, Kalantzopoulou, van Wijngaarden and Driessen2022) – types of landscape that have only recently been subject to systematic surveys.

Macro-regional syntheses have long demonstrated the potential of combining survey datasets (often with other types of information) to address large-scale social change during critical periods, including various parts of the Palaeolithic (Tourloukis and Harvati Reference Tourloukis and Harvati2018), the Later Neolithic to Early Bronze Age (Pullen Reference Pullen, Dietz, Mavridis, Tankosić and Takaoğlu2018), the Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age transition (Knodell Reference Knodell2021), the Byzantine/Frankish period (Kondyli Reference Kondyli, Caraher, Kourelis and Brooks Hedstrom2024), and periods of abandonment in modern times (Seifried and Stewart Reference Seifried and Stewart2021). These studies join classic works on landscape and demographic change based on survey evidence for the Classical-Hellenistic period (Bintliff Reference Bintliff1997) and in Roman times (Alcock Reference Alcock1993). Another important paper combines survey data with summed probability distributions of radiocarbon dates across Greece (which are disturbingly scarce in comparison to other regions) to examine long-term demographic and environmental change, demonstrating a trend of increasing human impact on land cover from the Late Bronze Age onward (Weiberg et al. Reference Weiberg, Bevan, Kouli, Katsianis, Woodbridge, Bonnier, Engel, Finné, Fyfe, Maniatis, Palmisano, Panajiotidis, Roberts and Shennan2019).

Recent fieldwork

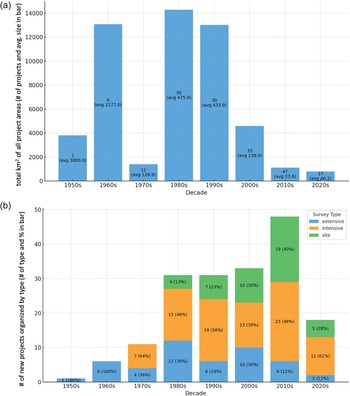

The aforementioned survey of Mediterranean surveys recorded 132 surveys from Greece as part of a wider database of 756 projects (Knodell et al. Reference Knodell, Wilkinson, Leppard and Orengo2023). To that I have added a number of more recent projects and others that were not included in the initial reckoning (e.g. many site surveys), based on new bibliography, project websites, personal communications, and information available in AGOnline to produce a total inventory of 204 projects (112 since 2000 and 50 since 2015). These data were mapped and classified according to a number of factors, including project area, scope, methodology, and start year (Fig. 2). In the summary below, I pay particular attention to coverage, methodological innovations, and significant results. Because the remit of this article is the last 25 years, with an emphasis on the last 10, I do not systematically refer to older projects, though I do include contextual references and new publications (older projects are included in maps and graphs).

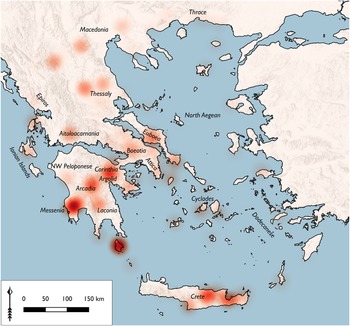

From the outset, we can observe several broad trends. First, survey areas have become smaller and survey methods more intensive over time. However, intensive surveys are by no means the rule, and there is even marked variation over what ‘intensive’ means. Second, surveys of different types are widely but unevenly distributed across Greece. A kernel-density analysis (heatmap) of survey projects shows the relative density of projects across the country, with individual projects weighted for intensity and coverage (Fig. 3). Zones of most intense survey activity include Messenia, the Corinthia and Argolid, east Crete, and Kythera. Arcadia, Boeotia, central and southern Euboea, the Cyclades, and central Crete have also seen substantial survey work, while other notable zones of activity appear in parts of Thessaly, Macedonia, and (recently) Thrace. Systematic surveys have been less widespread elsewhere, and there are several regions that are largely devoid of systematic survey work; namely, large portions of northern and western Greece. Third, we must note that approaches to sampling and coverage within the overall survey area vary from project to project, even for intensive surveys. Different approaches to mapping survey results include: artifact densities across continuous area (Fig. 4a); artifact densities within a sample of the project area as a whole (Fig. 4b); selected zones that were surveyed within an overall project area (Fig. 4c); and the distribution of archaeological sites as dots on a map (Fig 4d).

Fig. 3. Heat map of archaeological surveys in Greece, showing the density and intensity of projects; the heat map is based on the location and assigned ‘weight’ of projects according to the scale and intensity of survey work (weight = spatial coverage in km2 × intensity factor; intensity factors are the following, based on Cherry’s (Reference Cherry, Keller and Rupp1983, fig. 1) averages of sites per km2 discovered by intensive and extensive surveys: extensive = 0.08; intensive = 5.5; site = 10.

Fig. 4. Different types of areal coverage in archaeological surveys, as represented in maps of project areas: (a) the Mazi Archaeological Project (Knodell, Fachard and Papangeli Reference Knodell, Fachard and Papangeli2017: 147); (b) the Kythera Island Project (Kiriatzi and Broodbank Reference Kiriatzi and Broodbank2011: fig. 1); (c) the Pylos Regional Archaeological Project (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Alcock, Bennet, Lolos and Shelmerdine1997: 393); (d) the Nemea Valley Archaeological Project (Wright et al. Reference Wright, Cherry, Davis, Mantzourani, Sutton and Sutton1990: 598). From Knodell et al. Reference Knodell, Wilkinson, Leppard and Orengo2023, online resource 12, courtesy Journal of Archaeological Research.

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese has been an important nexus of survey activity since the UMME in the 1950s and 1960s (McDonald and Rapp Reference McDonald and Rapp1972). Since then, a number of successor projects have taken place in Messenia, including the Pylos Regional Archaeological Project (PRAP; ID146), which carried out intensive surveys and documentation of previously known sites in several zones in the vicinity of the Palace of Nestor (ca. 70km2 total; Davis and Bennet Reference Davis and Bennet2017) and an archaeological survey in the area of Iklaina (covering ca. 30km2; ID18471) focusing on the political geography of the Mycenaean period (Cosmopoulos Reference Cosmopoulos2016). Hope Simpson (Reference Simpson2014) has published a synthesis of the region in the Mycenaean period based on survey data from all of these projects (and other information). More detailed work on the prehistoric data collected by PRAP can be found in a recent PhD dissertation from the University of Cincinnati (Tsiolaki Reference Tsiolaki2022).

Laconia has also seen several decades of survey work, with the Laconia Survey (1983–89) documenting some 420 sites, ranging in date from the Neolithic to Veneto-Turkish periods, over ca. 70km2 northeast of Sparta (Cavanagh et al. Reference Cavanagh, Crouwel, Catling and Shipley2002). The successor Laconia Rural Sites Project (ID10538) selected 20 sites for very intensive treatment via surface collections, geophysical survey, and soil studies (Cavanagh et al. Reference Cavanagh, Mee, James, Brodie and Carter2005). More recent work in Laconia has included a survey of about 1km2 at and around the recently discovered Mycenaean palace of Agios Vasileios (Wiersma et al. Reference Wiersma, Bes, Van IJzendoorn, Wiznura and Voutsaki2022; ID17881). The detailed site survey, alongside excavations, suggests a relatively small palatial site of 4–6ha in the Mycenaean palatial period, following a sudden expansion in LH IIIA, and a relatively early end to occupation in LH IIIB1; remains from Classical to Roman periods were indicative of small-scale rural activity, while there seems to have been an uptick in medieval and later times. Since 2024 a field survey associated with the Amykles Research Project (ID19587) has carried out surface collections and geophysical survey in a small zone (0.6km2) to the south of the Amyklaion, the presumed location of an associated settlement; this is part of the larger Belonging in/to Lakonia Project of the University of Münster. In Mani, a recent survey was carried out by the Diros Project, alongside excavations, over a small area (2.5km2) near Alepotrypa Cave (Pullen et al. Reference Pullen, Galaty, Parkinson, Lee, Seifried, Papathanasiou, Parkinson, Pullen, Galaty and Karkanas2018). New work by the Southern Mani Archaeological Project (SMAP) is a multi-method, diachronic survey, which builds on previous work at Diros and other landscape research in the region by the codirectors (Seifried, Gardner and Tatum Reference Seifried, Gardner and Tatum2023; Gardner Reference Gardner2024). In its initial field season in 2025, the SMAP team recorded material dating from the prehistoric period through the Ottoman period and mapped the castle of Achilleio (W. Parkinson and C. Gardner pers. comm.).

Several projects have taken place in Arcadia as well. The PaGE Project of the Megalopolis basin was a targeted survey of Pleistocene sediments that discovered Lower, Middle, and Upper Palaeolithic material from several surface and stratified sites, including the Marathousa-1, which is currently the oldest chronometrically dated Lower Palaeolithic site in Greece at 400–500kya (Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Tourloukis, Panagopoulos and Harvati2018). Also near Megalopolis, the Mt Lykaion Excavation and Survey Project (ID19635) has carried out topographical, geophysical, and architectural studies, alongside excavations, since 2004, including architectural and geophysical surveys of the main sanctuary sites of Zeus and Pan; the project is also involved in a larger plan to create a protected ‘Parrhasian Heritage Park’ of over 600km2 (Romano and Voyatzis Reference Romano and Voyatzis2015). In eastern Arcadia, three instantiations of the Norwegian Arcadia Survey (ID9169) have taken place since 1998, the most recent in 2016–17; these projects have focused on the wider region of ancient Tegea and aimed to contextualize the polis and sanctuary (Ødegard Reference Ødegard2005; Malmer Reference Malmer and Taunsend2018).

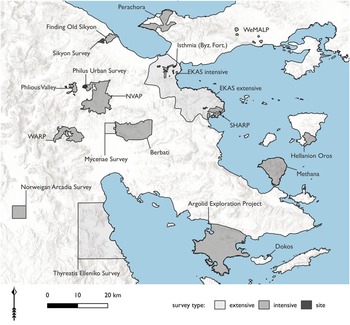

The Corinthia and the Argolid have the densest concentration of regional survey projects (Fig. 5). Several foundational projects took place in the 1970s–90s, beginning with the Argolid Exploration Project (ID14153; Jameson, Runnels and Van Andel Reference Jameson, Runnels and Van Andel1994). Recent studies of material from these projects present new data and interpretations. In another recent Cincinnati PhD dissertation, Cloke (Reference Cloke2016) provides a detailed study of the Geometric to Late Roman material collected by the Nemea Valley Archaeological Project (NVAP; Wright et al. Reference Wright, Cherry, Davis, Mantzourani, Sutton and Sutton1990), joining Athanassopoulos’s (Reference Athanassopoulos2017) volume on the medieval material; other recent NVAP volumes (I and III) focus on survey and (especially) excavations at the Neolithic and Bronze Age site of Tzoungiza (Pullen Reference Pullen2011; Wright and Dabney Reference Wright and Dabney2020). While not particularly recent, we should also distinguish between two additional projects, an urban survey of the ancient polis of Phlius, carried out as part of NVAP (Alcock Reference Alcock1991) and the later Basin of Phlious project (1998–2002), which took place in the valley to the west, and urged caution in the interpretation of surface assemblages, following the detailed study of geomorphological dynamics in the area (Casselmann et al. Reference Casselmann, Fuchs, Ittameier, Maran and Wagner2004).

Fig. 5. Survey project extents in the Corinthia and Argolid. Type is indicated based on the predominant coverage across the marked area; for example, if a project used both intensive fieldwalking and extensive exploration over a very large area, that large area will be marked as extensive.

In the Berbati Valley, east of Mycenae, Bonnier and colleagues (Bonnier, Finné and Weiberg Reference Bonnier, Finné and Weiberg2019) have identified boom and bust cycles by applying GIS-based spatial analysis to data from the Berbati-Limnes Survey (Wells Reference Wells1996). The Eastern Korinthia Archaeological Survey (EKAS, 1997–2003; ID907) has a new comprehensive publication that demonstrates the value of linking a digital publication with original project datasets and field records (Pettegrew Reference Pettegrew2024). A successor project – the Saronic Harbors Archaeological Research Project (SHARP, 2007–10; ID1887) – undertook surface collections and architectural documentation at the Mycenaean harbour site of Kalamianos and other prehistoric sites in the eastern part of the EKAS study area, showing the importance of maritime connections across the Saronic Gulf during the Late Bronze Age, and the development of coastscapes as a central concept (Tartaron et al. Reference Tartaron, Pullen, Richard, Tzortzopoulou-Gregory and Boyce2011; Tartaron Reference Tartaron2013). Also in the Saronic Gulf, a recent survey on Aegina has taken place at and around the sanctuary of Zeus at the Hellanion Oros, alongside excavations that have revealed significant remains from the Mycenaean, Geometric, and Roman periods; the survey aims to better contextualize these finds by documenting numerous rural structures and signs of multiperiod activity (Krapf et al. Reference Krapf, Chryssoulaki, Vokotopoulos, Michalopoulou and André2024).

Witmore (Reference Witmore2020) provides a highly original reengagement with survey data throughout the Corinthia and the Argolid in the form of a chorography – a tradition that can be traced back to Pausanias, but that has been largely absent in modern surveys. In 27 ‘segments’ from Corinth to Hermione and the Saronic Gulf, Witmore provides thick descriptions of places and landscapes as palimpsests, revisiting the work of several foundational survey projects: the Argolid Exploration Project, the Methana Survey (ID8113), NVAP, and EKAS.

Another recent project in the eastern Peloponnese is the Western Argolid Regional Project (WARP, 2014–17; ID8916), which, in the tradition of NVAP, emphasizes continuous and as-comprehensive-as-possible coverage over the study area (ca. 18km2 out of the 30km2 study area; Gallimore et al. Reference Gallimore, James, Caraher, Nakassis, Rupp and Tomlinson2017; Erny and Caraher Reference Erny and Caraher2020; James et al. Reference James, Nakassis, Caraher, Gallimore, Erny, Fernandez, Frankl, Friedman, Godsey and Gradoz2024). The project covers the broader area of the Inachos river valley, which also comprises a series of land routes between the Argolid (namely Argos itself) and eastern Arcadia. While finds were documented from the Neolithic period onward, the periods of most substantial occupation seem to have been in Classical-Hellenistic, Roman, and Early Modern. The project is also noteworthy for its high-resolution collection methods (collecting and analysing all pottery, rather than limiting field collection to diagnostics) and for the open, early publication of its field manual, a practice that should be encouraged for all projects (Caraher et al. Reference Caraher, Gallimore, Nakassis and James2020).

The Sikyon Urban Survey (ID107) bears mentioning as a well-published model of an urban survey that applied multi-disciplinary techniques to understanding a city and its countryside in the long term (Lolos Reference Lolos2011, Reference Lolos2021). Since 2015 a project has set out to find and document the pre-Hellenistic city of ‘Old Sikyon’ by carrying out a survey of the plain below and to the east of the later site (Müth-Frederiksen et al. Reference Müth-Frederiksen, Kissas, Winther-Jacobsen, Frederiksen, Donati, Giannakopoulos, Papathanasiou, Rabbel, Stümpel and Rusch2015). These projects, as well as other recent work at Aigeira and Lousoi, are included in a recent volume comparing microregions in the northern Peloponnese (Baier and Gauß Reference Baier and Gauß2025). On the other side of the Corinthian Gulf, the Perachora Peninsula Archaeological Survey began in 2020, carrying out intensive fieldwalking in the western part of the peninsula, in order to follow up on the earlier extensive surveys of Payne (Reference Payne1940), Dunbabin (Reference Dunbabin1962), and Tomlinson (Reference Tomlinson1969). In addition to systematic fieldwalking across the landscape and artifact collections at previously noted sites, lidar documentation of the survey area in 2024 has already led to the discovery of new Mycenaean and Archaic-Classical sites, as well as many other anomalies that await systematic ground verification (Lupack et al. Reference Lupack, Weissova, Skuse, Ross, Sobotkova and Kasimiforthcoming).

The northwestern Peloponnese has seen surprisingly little systematic survey work, the main exception being in the vicinity of Olympia, where the Olympia Area Survey has done fieldwork since 2015 in three zones: the Kladeos Valley and Archaia Pisa, Salmone, and Epitalion (Eder et al. Reference Eder, Gehrke, Kolia, Lang, Obrocki and Vött2019). A previous extensive survey, focused on the ancient settlement and topography of Triphylia, examined the area south of the Alpheios river, providing another perspective (Heiden and Rohn Reference Heiden, Rohn, Matthaei and Zimmermann2015). By focusing on a major sanctuary, rather than a city, the Olympia Area Survey provides new perspectives on ancient religion, as well as settlement and land use; it also provides a long-term view of a place of particular confluence, at the centre of a panhellenic network.

Attica and the Megarid

For a long time, very little intensive survey work had been undertaken in Attica, though we should mention Lohmann’s (Reference Lohmann1993) groundbreaking study of the deme of Atene and long-term work in the Lavriotiki (Hulek Reference Hulek2023). This lack of widespread survey was in large part due to the scale of development across the region, even by the later twentieth century, when intensive survey techniques were being developed. For this reason, historical maps such as Curtius and Kaupert’s Karten von Attika (Reference Curtius and Kaupert1895–1903) are particularly important for understanding premodern modes of landscape organization, and even the location of now destroyed archaeological sites.

In spite of these challenges, a number of projects have taken place over the last decade around the borders of Attica. In northwest Attica, the Mazi Archaeological Project (MAP; ID8174) has intensively surveyed the Mazi Plain (2014–17), in order to understand this borderland diachronically and contextualize the well-known fortified sites of Eleutherai and Oinoe and the Byzantine monastery of Osios Meletios (e.g. Knodell, Fachard and Papangeli Reference Knodell, Fachard and Papangeli2017; Fachard et al. Reference Fachard, Murray, Knodell and Papangeli2020; Kondyli and Craft Reference Kondyli and Craft2020). The neighbouring Skourta Plain was also the subject of a survey in the 1980s (Munn and Munn Reference Munn, Munn and Fossey1989). Since 2019, the Kotroni Archaeological Survey Project (KASP; ID19627) has worked near Marathon, in the environs of ancient Aphidna; this project brought a suite of remote sensing methods to bear, alongside systematic fieldwalking, and was also an early adopter (in Greece) of archaeological lidar analysis (Agapiou et al. Reference Agapiou, Dakouri-Hild, Davis, Andrikou and Rourk2022). Also, since 2019, the Bays of East Attica Regional Survey (BEARS; ID18591) has investigated the coastal zone between Brauron and Porto Rafti, including several small islets and the headland of Koroni (Murray et al. Reference Murray, Pratt, Stephan, McHugh, Erny, Psoma, Lis and Sapirstein2021; Reference Murray, Godsey, Frankl, Lis, Erny, Stephan, Sapirstein, McHugh and Pratt2023). While, on the mainland, surveyors faced several challenges from dense modern development, Raftis Island revealed a major settlement of the post-palatial Bronze Age (LH IIIC), which must correspond with the famous cemetery at Perati of the same date; significant Late Roman remains were also found on the island. Other major findings include a Neolithic–Early Bronze Age lithics scatter on the Pounta peninsula, and a multiperiod ceramic production site at Praso. At Koroni, the team discovered material that predates the third-century BC military installation that the site is best known for and mapped hundreds of walls and dozens of structures that were left out of the plans prepared by the excavators in the 1960s (Vanderpool, McCredie and Steinberg Reference Vanderpool, McCredie and Steinberg1964).

To the west, the Western Megaris Archaeological Landscape Project (WeMALP) has investigated five distinct zones between Megara and the Geraneia mountains. The main goal of the project is to carry out detailed surveys of a number of rural sites across the study area, which of course is only a small fraction of the ca. 450km2 territory of the ancient Megarians (Farinetti and Avgerinou Reference Farinetti and Avgerinou2023).

Boeotia and Phokis

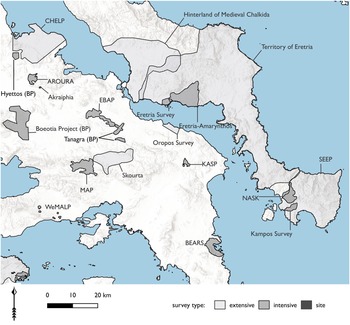

While the initial fieldwork of the long-running Boeotia Project was carried out from the late 1970s through to the 1980s, research has continued in various forms, including architectural mapping, finds analysis, aerial photography, and new fieldwork, focused on the cities of Hyettos, Haliartos, and Tanagra, as well as the Valley of the Muses (Fig. 6). Bintliff (Reference Bintliff2025) provides a summary of recent work and publications of the Boeotia Project, and in another publication has summarized the work of the first 36 years of the project (Bintliff Reference Bintliff, Bintliff and Rutter2016). The first two published volumes present the results of intensive surveys of the hinterland and city of Thespiai (Bintliff, Howard and Snodgrass Reference Bintliff, Howard and Snodgrass2007; Bintliff et al. Reference Bintliff, Farinetti, Slapšak and Snodgrass2017), while a third focuses on Hyettos (Bintliff, Farinetti and Snodgrass Reference Bintliff, Farinetti and Snodgrass2025). It is also worth mentioning Farinetti’s (Reference Farinetti2011) study of Boeotia, which provides the most comprehensive synthesis of survey results across Boeotia as a whole up to the point of publication.

Fig. 6. Survey project extents in central Greece.

The Eastern Boeotia Archaeological Project (EBAP, 2007–09; ID18585) carried out an intensive survey in the area around and between the modern villages of Eleona, Arma, and Tanagra. This zone was selected mostly because of known sites; namely, the Mycenaean cemetery at Tanagra and the site of ancient Eleon (named in the Linear B tablets from Thebes), which is the subject of the main publication of the survey to date, as well as ongoing excavations since 2011 (Aravantinos et al. Reference Aravantinos, Burke, Burns, Fappas, Lupack and MacKay2016).

In the Kopaic Basin, the Archaeological Reconnaissance of Uninvestigated Remains of Agriculture (AROURA) project (ID3064) undertook a large-scale geophysical survey, along with limited surface collections, in the immediate vicinity of Gla (Lane et al. Reference Lane, Aravantinos, Horsley and Charami2020). This project sheds new light on the drainage of the Kopaic Basin and the construction of Gla, all investigated alongside a model for land allotments derived from Linear B documents. Successor projects – Mycenaean Northeast Kopais Project (ID19597) and Kopaic Cultures, Economies, and Landscapes – have continued work in the region through geophysical survey, surface collections, and excavations (Lane Reference Lane2023). Also in this area, a recent lidar survey has been carried out at the site of Akraiphia, revealing architectural remains and aspects of the settlement plan that were previously undetectable (Lucas Reference Lucas2025).

To the west, the Kephissos Valley Project has investigated a large area (145km2) since 2018 (Sporn, Kounouklas and Kennedy Reference Sporn, Kounouklas and Kennedy2025), building on earlier work at Elateia and Tithorea (Sporn, Kounouklas and Laufer Reference Sporn, Kounouklas and Laufer2021; Kounouklas and Laufer Reference Kounouklas, Laufer, Sporn, Farnoux and Laufer2024). This project utilizes a combination of satellite imagery and lidar data to analyse the landscape, documenting over 2,700 areas of interest. At the site level, ground verification of lidar, architectural study, and geophysical survey have been applied to document several urban and rural sites, including Elateia, the sanctuary of Athena Kranaia, Agia Marina, Paliophiva, and the site of Synteleio (Sporn and Kennedy Reference Sporn and Kennedy2025). While this project has largely eschewed systematic fieldwalking and regional-scale artifact collection as a primary method, it has generated impressive results and demonstrated a powerful approach to regional survey in a large area of great historical significance.

Euboea

In Euboea, a series of recent projects make the southern and central parts of the island some of the better investigated archaeological zones in Greece. The north of the island has seen no systematic survey work, besides its inclusion in the island-wide survey of prehistoric sites on the island in the 1950s (Sackett et al. Reference Sackett, Hankey, Howell, Jacobsen and Popham1966). Since 2021, the Hinterland of Medieval Chalkida project is investigating the central part of the island via extensive survey over a large area (ca. 350km2) and targeted, intensive surveys of three selected sites (Vroom et al. Reference Vroom, Kostarelli, Blackler, Kalantzis-Papadopoulos and Kolvers2024). In this case, extensive survey means mostly the study and documentation of previously known sites, rather than exploration intended to find new ones.

In 2021, the Swiss School began a new intensive landscape survey in the area between Eretria and Amarynthos, uniting the long-standing excavations at Eretria with the more recent work at the sanctuary of Artemis Amarysia (ID19601; Fachard et al. Reference Fachard, Simosi, Krapf, Saggini, Kyriazi, André, Chezeaux, Verdan and Theurillat2024). Significant discoveries include the sacred way linking the city and sanctuary, parts of the ancient necropolis to the east of Eretria, and a number of rural sites in the eastern hinterland of the city. Also noteworthy was the development of a lidar-led survey methodology to accompany extensive exploration and feature documentation over an area of 240km2; this is currently the largest archaeological lidar acquisition in Greece (Fachard et al. Reference Fachard, Simosi, Krapf, Saggini, Kyriazi, André, Chezeaux, Verdan and Theurillat2024). This work follows on an older survey of the immediate environs of Eretria (Simon Reference Simon2002) and Fachard’s (Reference Fachard2012) extensive survey of the territory of the polis of Eretria, extending as far south as Styra.

Finally, the Karystia has seen a dense concentration of extensive and intensive survey projects, beginning with Keller’s (Reference Keller1985) extensive one-man survey of the region and the establishment of the Southern Euboea Exploration Project (SEEP; ID453), part of which was published in volumes on the Paxhimadi and Bouros-Kastri peninsulas (Cullen et al. Reference Cullen, Talalay, Keller, Karimali and Farrand2013; Wickens et al. Reference Wickens, Rotroff, Cullen, Talalay, Perlès and Mccoy2018). A number of successor projects followed, most recently the Karystian Kampos Project (ID453) in the western hinterland of Karystos (Tankosić and Chidiroglou Reference Tankosić and Chidiroglou2010) and the Norwegian Archaeological Survey of the Karystia (NASK), which moved northwest and upland to the Katsaronio plain, where discoveries included, among other things, the major Neolithic site of Gourimadi, under excavation since 2018 and home to the largest collection of obsidian projectile points known in the Aegean (Tankosić et al. Reference Tankosić, Laftsidis, Psoma, Seifried and Garyfalopoulos2021).

Phthiotis and Thessaly

Several new projects in Phthiotis and Thessaly have revealed new information about these regions. The Central Achaia Phthiotis Survey (CAPS, 2019–24; ID19598) is an intensive survey of the area north of Kastro Kallithea, building on a previous urban survey and other work at that site (Haagsma et al. Reference Haagsma, Karapanou, Surtees and Mazarakis-Ainian2015; Surtees Reference Surtees2012). The CAPS project surveyed an area of approximately 15km2, including a lidar acquisition of over 9km2, used for remote sensing and extensive survey, which identified several Early Iron Age tholos tombs in a relatively small area, suggesting potential for the application of lidar technology across a wider area (Haagsma et al. Reference Haagsma, Karapanou, Aiken, Canlas, Chykerda and Middleton2025). In the western Spercheios Valley, the Makrakomi Archaeological Landscape Project carried out an intensive survey in the vicinity of Profitis Elias/Asteria, documenting a nucleated Classical-Hellenistic settlement and its surroundings (Papakonstantinou et al. Reference Papakonstantinou, Penttinen, Tsokas, Tsourlos, Stampolidis, Fikos, Tassis, Psarogianni, Stavrogiannis, Bonnier, Nilsson and Boman2013). Across the Spercheios Valley as a whole, the Mycenaean Spercheios Valley Archaeological Project has carried out a programme of GPS, geophysical, and geomorphological documentation of previously known Mycenaean sites across the region (Malaperdas et al. Reference Malaperdas, Maggidis, Karantzali and Zacharias2023).

In the northeastern plain of Karditsa, the Palamas Archaeological Project has undertaken site surveys, geophysical surveys, and excavations at several locations, including Vlochos, Metamorfosi, Agios Dimitrios, and the Chomatokastro at Mataragka (Vaiopoulou et al. Reference Vaiopoulou, Rönnlund, Tsiouka, Klange, Pitman, Randall, Potter and Manley2024). This builds on previous work of the Vlochos Archaeological Project (ID6788), where a series of non-invasive methods were deployed to document multiple phases of habitation at the large Classical-Hellenistic city, which the investigators tentatively associate with Phakion, though they acknowledge several other possibilities (Vaiopoulou et al. Reference Vaiopoulou, Whittaker, Rönnlund, Tsiouka, Klange, Pitman, Potter, Shaw, Hagan, Siljedahl, Forsén, Chandrasekaran, Dandou, Forsblom Ljungdahl, Pavilionytė, Scott-Pratt, Schager and Manley2020). This project offers a model example of detailed digital documentation that did not include systematic artifact collection. Aerial photography, architectural study, geophysical survey (magnetometry and GPR), and geochemical prospection revealed a detailed plan of the acropolis and lower town. One of the most impressive innovations of this project was its interpretations of imagery of crop marks and snow marks, captured after a January 2019 snowfall, where the differential rate of melting caused by near-surface architecture allowed for the identification of plans of several buildings (Fig. 7). Another multi-site survey is the Kedros-Anavra Archaeological Landscape Project (KAALP), which (since 2024) is investigating two pairs of adjacent archaeological sites: Alonaki and Violi, and Chelonokastro (ancient Orthe) and Kolokria, all of which are located in the Agrafa foothills around the southwestern corner of the plain of Karditsa (A. Blomley pers. comm.). An additional aim of KAALP is to put survey results in dialogue with rescue excavations that have been carried out at these sites (e.g. Karagiannopoulos Reference Karagiannopoulos, Antonopoulou and Petrounakos2022). Other remote sensing work in the plain of Karditsa used a photogrammetric and multi-image approach to historical aerial photographs, maps, and satellite imagery to identify hundreds of mounded archaeological features, with initial samples investigated by ground verification associated with the Neolithic period (Orengo et al. Reference Orengo, Krahtopoulou, Garcia-Molsosa, Palaiochoritis and Stamati2015).

Fig. 7. Geophysical survey and snow marks interpretation at Vlochos. From Vaiopoulou et al. Reference Vaiopoulou, Whittaker, Rönnlund, Tsiouka, Klange, Pitman, Potter, Shaw, Hagan, Siljedahl, Forsén, Chandrasekaran, Dandou, Forsblom Ljungdahl, Pavilionytė, Scott-Pratt, Schager and Manley2020: fig. 12, courtesy of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, the Ephorate of Antiquities of Karditsa, and the Swedish Institute at Athens.

Additional site surveys have taken place at Skotoussa (ID19824; La Torre et al. Reference La Torre, Campagna, Di Giacomo, Donato, Karapanou, Miano, Mollo, Noula Karpeti, Papale, Puglisi, Toscano Raffa and Venuti2017) and at Melitaia, the latter involving a detailed lidar survey of the site (Rönnlund Reference Rönnlund2025). Drone-based lidar surveys have been done at several sites in the vicinity of Halos: Magoula Platoniotiki, the acropolis, and Voulokaliva (Waagen et al. Reference Waagen, Heymans, Scholte, Kriek and Stissi2025). This work follows several stages of previous survey in the area, including extensive survey, intensive fieldwalking, site revisitation, and methodological tests (1990–2006; 2011–13; see Stissi et al. Reference Stissi, Waagen, Efstathiou, Reinders, Rondiri, Mamaloudi and Stamelou2015 for a summary).

One further, specialized, project that is worth mentioning is the Pelion Cave Project, which documented ca. 160 caves and rock shelters and compiled a rich collection of ethnographic material (ID808; Andreasen et al. Reference Andreasen, Pantzou, Papadopoulos and Darlas2017). This project documented widespread evidence of cave use, mostly in the form of prehistoric and historical pottery, but including also lithics, engravings, and small finds from the Palaeolithic period up to the Second World War.

Recent site surveys in Thessaly and Phthiotis have produced high-quality work in a number of locations. However, only a relatively small number of regional-scale intensive survey projects have occurred in the area. This is a pity, given the hundreds of sites and micro-landscapes of historical interest – for many periods – that are found in the region.

Western Greece and Epiros

A low density of systematic surveys is even more noticeable in western Greece. Recent surveys are limited to site surveys at Kalydon (Dietz Reference Dietz2011) and a lidar survey of the site of Kastri-Pantosia, which used a suite of open-source solutions to process, analyse, and interpret a complex dataset (Abate et al. Reference Abate, Roubis, Aggeli, Sileo, Amodio, Vitale, Frisetti, Danese, Arzu, Sogliani, Lasaponara and Masini2025). Regional surveys are rarer, limited to the now venerable Aetolian Studies Project (Bommeljé et al. Reference Bommeljé, Doorn, Deylius, Vroom, Bommeljé, Fagel and van Wijngaarden1987; ID15887), the Nikopolis Project (Wiseman and Zachos Reference Wiseman and Zachos2003; ID15940), and the more recent Thesprotia Expedition (ID1929), focused on the Kokytos Valley (Forsén Reference Forsén2019). Part of the reason for this scarcity of surveys is the landscape, comprising the southern extent of the Pindus range, which is mountainous and thickly vegetated (this also applies to much of the landscape in the northwest Peloponnese). This environment has required researchers to rely on different types of evidence, especially rescue excavations, to address regional-scale questions (mostly concerning the Roman and Byzantine periods: e.g. Bowden Reference Bowden2003; Veikou Reference Veikou2012; Pirée Iliou Reference Pirée Iliou2022). Challenges aside, this type of landscape is exceptionally fertile ground for certain types of remote sensing, most notably lidar, which has the distinct advantage of being able to detect surface anomalies beneath vegetation cover. Lidar surveys of similar types of landscape in Italy have resulted in the discovery of hundreds of previously unknown archaeological sites, especially hillforts (Fontana Reference Fontana2024).

Ionian Islands

The Ionian Islands have seen a number of systematic surveys over the last two decades. On Kephalonia, the Livatho Valley Survey (2003—07; ID430) carried out a field survey of ca. 30km2 in the southwestern part of the island, and was designed to investigate prehistoric settlement and land use in the territory of the Greco-Roman city of Krane and around the castle of St George (Souyoudzoglou-Haywood Reference Souyoudzoglou-Haywood, Gallou, Georgiadis and Muskett2008). This followed mixed intensive and (mostly) extensive survey work in the 1990s, which examined an area of ca. 500km2 in the eastern part of the island, encompassing the territories of ancient Same and Pronnoi (Randsborg Reference Randsborg2002). Beginning in 2006, the Zakynthos Archaeology Project (ID4457) carried out surveys in three distinct areas in the southern part of the island, where they collected finds datable to as early as the Middle Palaeolithic period and through to the Holocene (van Wijngaarden et al. Reference Van Wijngaarden, Sotiriou, Pieters, Bogaard and De Gelder2015). Finally, since 2010, the Inner Ionian Archipelago Survey (ID2620) has carried out intensive surveys and targeted excavations on 10 small islands. The project aimed to investigate the history of occupation on these islets diachronically, but with a particular focus on the extent and chronology of evidence from the Middle Palaeolithic period (Galanidou et al. Reference Galanidou, Vikatou, Gatsi-Stavropoulou, Vasilakis, Staikou, Iliopoulos, Veikou, Forsén, Morgan, Vroom, Papoulia, Zervoudakis, Prassas and Vikatou2018).

Macedonia and Thrace

Survey projects in northern Greece are thinly distributed, at least in comparison with regions to the south. In western Macedonia, several projects have taken place in the broader area of Grevena. One recent project (2021–23) has combined remote sensing and extensive survey strategies to study unpublished ‘legacy data’ of the diachronic extensive survey called the Grevena Project (ID11901, ID11170) carried out between 1986 and 1994 (Wilkie Reference Wilkie1999). The new project documented sites previously recorded by the Grevena Project and discovered several new ones, finding an impressive 64% more sites than have been reported by the initial project, though publication is incomplete (Apostolou et al. Reference Apostolou, Venieri, Mayoral, Dimaki, Garcia-Molsosa, Georgiadis and Orengo2024). A number of surveys focused on the Palaeolithic period have also taken place in northern Greece, including the work of the Samarina Survey and the Aliakmnon Paleolithic/Paleoanthropological Survey, both also in the wider area of Grevena (Efstratiou et al. Reference Efstratiou, Biagi, Elefanti, Karkanas and Ntinou2006; Harvati et al. Reference Harvati, Panagopoulou, Karkanas, Athanassiou, Darlas and Mihailović2008). Farther north, another specialized project has focused on the caves of the northernmost peninsula of the Greek part of Lake Prespa, documenting use mainly in Late Neolithic, Early Bronze Age, Byzantine, and post-Byzantine periods (Kontos, Michelaki and Miteletsis Reference Kontos, Michelaki and Miteletsis2017).

For the Classical period, recent site surveys have occurred at Methone (Morris et al. Reference Morris, Papadopoulos, Bessios, Athanassiadou and Noulas2020) and Olynthos (ID8114; Nevett et al. Reference Nevett, Tsigarida, Archibald, Stone, Horsley, Ault, Panti, Lynch, Pethen, Stallibrass, Salminen, Gaffney, Sparrow, Taylor, Manousakis and Zekkos2017), with the Pella Urban Dynamics Project developed as a successor to the latter (https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/pella/ ). Since 2010, the Anthemous Valley Archaeological Project has investigated the Anthemous river valley, located southeast of Thessaloniki, combining traditional archaeological prospection with a number of geophysical and geomorphological techniques, with a focus on landscape evolution from the Neolithic period to the Early Iron Age (Andreou, Czebreszuk and Pappa Reference Andreou, Czebreszuk and Pappa2016; Niebieszczański et al. Reference Niebieszczański, Czebreszuk, Hildebrandt-Radke, Vouvalidis, Syrides, Tsourlos and Spychalski2019). Across the region of Macedonia as a whole, Evangelidis (Reference Evangelidis2022) offers a synthesis of regional survey data from the Roman period.

In Thrace, a number of survey projects are reported in the recent edited volume, Surveying Aegean Thrace (Avramidou and Donati Reference Avramidou and Donati2023). These follow on the foundational explorations of Bakalakis (Reference Bakalakis1959) and various earlier projects focused on contextualizing the Neolithic landscape of Sitagroi (Blouet Reference Blouet, Renfrew, Gimbutas and Elster1986) and the Survey Project of the Rhodope Plain, whose primary interest was the documentation of evidence for the Pleistocene and early Holocene landscape and human activities therein (Efstratiou and Ammerman Reference Efstratiou, Ammerman and Iakōvou2004). More recently, the MapFarm Project (mapping the early farmers of Thrace) carried out systematic artifact collection, geophysical surveys, borehole sampling, and radiocarbon dating at eight Neolithic sites across the regions of Rhodope and Xanthi, documenting significant Late Neolithic ceramic scatters at six of them (Urem-Kotsou et al. Reference Urem-Kotsou, Sgouropoulos, Kotsos, Chrysaphakoglou, Chrysaphi and Skoulariki2022).

Other recent projects include several multi-disciplinary landscape surveys with diachronic scopes. Beginning in 2013, the Molyvoti Thrace Archaeological Project (MTAP; ID6182) has carried out excavation at the site the investigators identify as ancient Stryme and survey in the surrounding area (ca. 20km2), revealing a landscape that was used consistently from the Archaic period onward; several tumuli were also discovered along the course of presumed roads (Arrington et al. Reference Arrington, Terzopoulou, Tasaklaki, Makris and Hudson2023; Reference Arrington, Terzopoulou, Tasaklaki and Tartaron2025). The Archaeological Project at Abdera and Xanthi (APAX; 2015–19) used similar methods to investigate three zones, totalling ca. 10km2: the coastal region of the ancient city of Abdera and its environs, the northern end of the Xanthi alluvial plain, and a highland plain in the Rhodope range (Georgiadis et al. Reference Georgiadis, Kallintzi, Garcia-Molsosa, Orengo, Kefalidou and Motsiou2022). Finally, the Peraia of Samothrace Project (PSP) has examined four areas of interest between the Rhodope mountains and the coast, using a combination of remote sensing, intensive fieldwalking, and geophysics (Avramidou et al. Reference Avramidou, Donati, Papadopoulos, Sarris, Karadima, Pardalidou, Aitatoglou, Tasaklaki, Sirris, Avramidou and Donati2023).

Northern Aegean Islands

On Samothrace itself, a recent publication of the Samothrace Archaeological Survey (SAS), which did fieldwork in the 1980s, and new lidar-based remote sensing and fieldwork – the Samothrace Lidar Project (SaLiP) – provide much new information about the island. For the former, a survey of ca. 14km2 of contiguous area in the western part of the island revealed significant prehistoric sites, as well as widespread evidence from the Archaic to Byzantine periods; large numbers of trade amphoras highlight the significance of the island as a long-term nexus of activity, not least for its famous sanctuary (Matsas et al. Reference Matsas, Laftsidis, Hudson, Levine, Makris, Page, Avramidou and Donati2023). The American Excavations Samothrace project (ID19596) has recently undertaken a survey of the ancient city of Samothrace (Palaiopolis) and since 2024 the new programme of lidar analysis has opened up landscape investigations in several diverse landscapes across the island (Matsas et al. Reference Matsas, Wescoat, Witmore, Page, Garrison and Manquen2025). Lidar imagery is revealing in multiple places, but its utility is especially clear in depicting the landscape near the site of Christos, in the north of the island, where a ruined medieval village is heavily obscured by vegetation and rubble, both in aerial imagery and on the ground (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Lidar imagery and aerial photo of the area of Christos, a ruined medieval village in northern Samothrace. Map by B. Manquen, after fig. 10 in Matsas et al. Reference Matsas, Wescoat, Witmore, Page, Garrison and Manquen2025, courtesy of SaLiP.

On Lemnos, surveys over the last decade have discovered at least three previously unknown Epipalaeolithic sites on the island, as well as four sources of knappable raw material (Efstratiou et al. Reference Efstratiou, Biagi, Starnini, Kyriakou and Eleftheriadou2022). One of these (Ouriakos) is radiocarbon-dated to the Younger Dryas; the assemblages of all of the sites signal technological affinities with contemporary sites in Anatolia. Another period-specific survey compared the settlement patterns of Lemnos and Thasos during Late Byzantine times, carrying out an extensive survey that documented 93 sites on Lemnos and 17 on Thasos (Kondyli Reference Kondyli2022).

On Lesvos, a survey in the 1990s focused on the ancient city of Eressos (Schaus and Parish Reference Schaus and Parish1996), while a more recent series of surveys and excavations at Rodafnidia revealed important finds dated to the Middle Pleistocene, including Acheulean and Middle Palaeolithic materials (Galanidou et al. Reference Galanidou, Athanassas, Cole, Iliopoulos, Katerinopoulos, Magganas, McNabb, Harvati and Roksandic2016). In the Sporades, the Ancient Skopelos Survey (ASkoS), which began in 2024, has so far carried out a reconnaissance survey to identify areas of interest across the island for more systematic documentation, including intensive survey, lidar analysis, geoarchaeological investigations, palaeoenvironmental reconstruction, and geophysical prospection. In 2024, project activities focused on reconnaissance and intensive survey, including the investigation of seven sites in the eastern part of the island and the ancient quarry south of Chora (F. Franković pers. comm.; https://askos.archeologia.uw.edu.pl/ ). Also noteworthy is a one-person survey of the island of Skyros, which documented 96 sites using a combination of extensive exploration, documentation of previously known sites, and systematic fieldwalking at sites of particular interest, with a focus on the Late Roman to Early Modern periods (Karambinis Reference Karambinis2015).

On Chios, the Emborio Hinterland Project (ID20638) has carried out an intensive field survey of ca. 10km2 in the vicinity of Emborio, the site of long-term excavations by the British School (Hood Reference Hood1981). This survey involves a high degree of spatial resolution, with fieldwalkers spaced 10m apart and recording finds every 10m to create a resolution of 10 × 10m grid squares. Significant findings include a range of new sites from the prehistoric, Greco-Roman, and medieval periods. An earlier survey, the Kato Phana Archaeological Project, also in the southern part of the island, investigated a 3km2 area near the sanctuary of Apollo Phanaios through surface survey, mapping, cleaning, and geophysical survey (Beaumont and Archontidou-Argyri Reference Beaumont and Archontidou-Argyri1999).

From 2021 to 2024, the West Area of Samos Archaeological Survey (WASAP; ID20635) carried out extensive and intensive survey in several zones throughout the western part of the island (Christophilopoulou et al. Reference Christophilopoulou, Huy, Loy, Mac Sweeney and Mokrišová2025; Loy et al. Reference Loy, Argyraki, Christophilopoulou, Delli, Evans, Huy, Katevaini, Mac Sweeney, Mokrišová, Regazzoni and Vasileiou2025). The project was designed to fill an archaeological blank spot on an island whose main ancient sites (the polis at Pythagorio and Heraion sanctuary) are located on the east side of the island (which has also seen no systematic survey work).

Southern Aegean Islands

The Dodecanese, too, have only recently seen systematic surveys, and only on a few islands. From 2018 to 2023, the Kos Archaeological Survey Project has carried out fieldwork in three main zones: the area of the ‘Serraglio’ on the east side (the largest zone), the Kastro of Palaio Pyli, in the centre of the island, and near the bay of Kephalos and Aspri Petra Cave on the west side of the island. While the scope of the project is diachronic, publication up to this point has focused on the Late Bronze Age finds, especially the discovery of a major prehistoric site at Agios Pandeleimon, now the largest known on the island (Vitale et al. Reference Vitale, Marketou, McNamee and Michailidou2022). A previous intensive survey (2003–05) focused on the site and territory of the ancient deme of Halasarna (Kopanias Reference Kopanias2009; Georgiadis Reference Georgiadis2012; ID9743). On Rhodes, a long-term project (since 2006) has carried out a variety of survey and excavation activities in the area of the ancient deme site of Kymisala, including work at the acropolis, necropolis, quarries, and a number of other locations (Stefanakis Reference Stefanakis2017; ID19754). On Karpathos, the Afiartis Survey (2006–16) investigated an area of 20km2 in the southern part of the island, where a particular interest was to clarify the prehistoric settlement pattern, especially in relation to Minoan Crete; Roman and modern finds were also abundant, among scattered remains of other periods (Klys Reference Klys2018). This intensive survey built upon the work of an earlier, extensive survey of the islands of Karpathos, Saros, and Kasos (Melas Reference Melas1985).

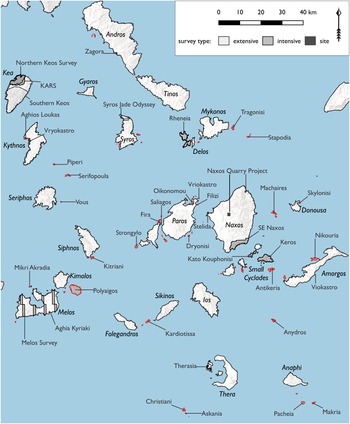

The Cyclades were home to two groundbreaking early surveys on Melos (Cherry Reference Cherry, Renfrew and Wagstaff1982) and on Kea with the Northern Keos Survey (Cherry, Davis and Mantzourani Reference Cherry, Davis and Mantzourani1991), but then saw little systematic survey work until relatively recently (Fig. 9). One recent project in the Cyclades, the Kea Archaeological Research Survey (KARS, 2012–14; ID19602) was a deliberate resurvey of the same area covered by the Northern Keos Survey in the 1980s (https://www.iihsa.ie/projects/the-kea-archaeological-research-survey-kars-project). This new work aimed to test the reliability of survey data and reproducibility of results and to increase the sample size; it also increased the overall survey area slightly and carried out site-based gridded collections in some new areas. The validity of the results of the earlier project has been confirmed.

Fig. 9. Survey project extents in the Cyclades, with survey type indicated and islands surveyed by the Small Cycladic Islands Project outlined in red (see online version).

Other intensive surveys have taken place mainly on small islands in various parts of the Cyclades. A survey of Therasia (2007–13), examined the entire island (ca. 9km2) through intensive fieldwalking (over 2km2), artifact collections, geophysical survey, geomorphological study, and excavations, providing also a detailed publication of methods and diachronic results (Sbonias and Tzachili Reference Sbonias and Tzachili2021).

Site surveys have been included in long-term programmes of excavation at sites of particular significance, such as at Zagora, on Andros (Beaumont, Miller and Paspalas Reference Beaumont, Miller and Paspalas2012), and at Vryokastro, the site of ancient Kythnos (Mazarakis Ainian Reference Mazarakis Ainian, Mendoni and Mazarakis Ainian1998); a broader programme of extensive survey was also carried out in the northeastern part of Kythnos by the ephorate (Papangelopoulou Reference Papangelopoulou2012).

A series of surveys have been carried out in relation to a wider programme of work on Keros and Dhaskalio (Renfrew et al. Reference Renfrew, Boyd, Athanasoulis, Brodie, Carter, Dellaporta, Floquet, Gavalas, Georgakopoulou, Gkouma, Hilditch, Krijnen, Legaki, Margaritis, Marthari, Moutafi, Philaniotou, Sotirakopoulou and Wright2022). The Keros Island Survey (2012–13; ID4284) provided intensive coverage of the entire island (15km2) and six islets to the south, using methods based on the Kythera and Antikythera surveys (see below). Results indicate main periods of occupation in the Early Bronze Age, Late Roman–Early Byzantine period, and Early Modern times, with the main centre of activity in the northwest of the island and other significant zones in the south-central part of the island. From 2015 to 2018, the Keros-Naxos Seaways Project conducted surveys on Kato Kouphonisi (3.5km2) and a coastal block of 10km2 in southeast Naxos, including the major Bronze Age sites of Spedos, Panormos, and Korfi t’Aroniou, in order to investigate the wider coastal landscape and seascape of Keros and Dhaskalio. A new, five-year programme of excavations by the Keros Project has an explicit focus on areas of interest identified by the archaeological surveys of Keros and Kato Kouphounisi, in an attempt to address fundamental questions concerning the relationship between surface assemblages and subsurface remains (M. Boyd pers. comm.).

Elsewhere on Naxos, two specialized survey projects have investigated quarries, highlighting the unique geologic resources of the island. The first is the Stelida Naxos Archaeological Project (2013–present), which investigated the Stelida hill and promontory in northwest Naxos, home to a significant chert quarry and stone tools dating from the Mesolithic and Upper, Middle, and Lower Palaeolithic periods (Carter et al. Reference Carter, Contreras, Holcomb, Mihailović, Skarpelis, Campeau, Moutsiou, Athanasoulis, Tomlinson and Rupp2017). Subsequent excavations and infrared stimulated luminescence dating confirmed this broad date range, with the oldest cultural material coming from strata dated to ca. 200kya (Carter et al. Reference Carter, Contreras, Holcomb, Mihailović, Karkanas, Guérin, Taffin, Athanasoulis and Lahaye2019). An unexpected contribution of this project was the discovery of a Minoan-style peak sanctuary on the top of the hill (Carter et al. Reference Carter, Mallinson, Mastrogiannopoulou, Contreras, Diffey, Lopez, Pareja, Tsartsidou and Athanasoulis2021). Since 2020, the Naxos Quarry Project has applied a range of methods – aerial photogrammetry, lidar, field survey, sculptural analysis, and architectural analysis – to investigate marble quarries and quarrying practices at several locations across the island, especially at Melanes and Apollonas, known for the monumental kouros statues that have remained in situ at each of them (Levine et al. Reference Levine, Indgjerd, Samdal and Kristensen2025; Levitan et al. Reference Levitan, Levine, Athanasoulis, Legaki, Paga, Campbell, Indgjerd, Vanden Broeck-Parant, Anevlavi, Jakobitsch and Liard2025). Another stone-oriented project is the Jade Odyssey Project, which in 2022 and 2024 identified four areas on Syros that were used for the production of jadeite tools (chiefly associated with the Neolithic period) in the area of Kampos and the neighbouring valleys (https://diathens.gr/en/projects/syros).

Across the archipelago as a whole, the Small Cycladic Islands Project (SCIP; ID18178) has carried out systematic, intensive surveys of 87 small, (mostly) uninhabited islands over the course of six field seasons (2019–24; Athanasoulis et al. Reference Athanasoulis, Knodell, Tankosić, Papadopoulou, Sigala, Diamanti, Kourayos and Papadimitriou2021; Knodell et al. Reference Knodell, Athanasoulis, Tankosić, Cherry, Garonis, Levine, Nenova and Öztürk2022; Reference Knodell, Athanasoulis, Cherry, Giannakopoulou, Levine, Nenova, Öztürk and Papadopoulou2025a). These islands ranged in size from less than 1ha to 18km2 (Polyaigos), although most were under 1km2 in size. Very few of these islands yielded no evidence of occupation or use, and many had remains of substantial material investment in the form of built features (structures, fortifications, agricultural installations) and surface ceramics and lithics. The comparative framework and results of the project have demonstrated a correlation between island size and intensity of occupation or use (an important distinction), as well as the connectedness of places long-dismissed as marginal. An acquisition of aerial lidar data has covered all islands subject to pedestrian survey by SCIP, as well as several larger, uninhabited islands (Knodell et al. Reference Knodell, Levine, Wege, Fielder-Jellsey and Athanasoulis2025b). Detailed study of the SCIP lidar has also revealed significant strengths and some weaknesses of lidar analysis though a self-critical analysis of feature identification, classification, and verification strategies (Manquen et al. Reference Manquen, Garrison, Knodell and Athanasoulis2025).

Rheneia has been subject to a systematic intensive survey by the Rheneia Archaeological Project (RAP) since 2019. Results have highlighted the ancient polis of Rheneia on the west side of the island and the cemetery of the Delians on the east side (the subject of long-term, collaborative study), with a densely constructed and inhabited agricultural landscape in between. RAP has recently integrated the aforementioned lidar data to evaluate it explicitly alongside other forms of remote sensing (namely, drone-based aerial photography and photogrammetry) (Papadopoulou et al. Reference Papadopoulou, Samaras, Fylaktos and Knodell2025). While Delos is usually left out of discussions of systematic surveys, it must be mentioned that it is perhaps more thoroughly investigated than any other island in the Aegean, at least from the perspective of architectural mapping (e.g. Moretti et al. Reference Moretti, Fadin, Fincker and Picard2015).

In the southwestern Aegean, Kythera and Antikythera have seen a number of surveys since the 1990s, when the Kythera Island Project (KIP; ID6544) and the Australian Paliochora-Kythera Archaeology Survey (APKAS) began work on different parts of the island. Publication is ongoing, and the main body of fieldwork has been supplemented recently by the KIP team at Palaiokastro and by the APKAS team with various remote sensing projects and other interventions (MacNeill Reference MacNeill2023). As successor project to KIP, involving many of the same people, the Antikythera Survey Project provided a hallmark example of a total island survey and methodological rigour that inspired many of the projects described above, not least through its relatively speedy publication (Bevan and Conolly Reference Bevan and Conolly2013).

Crete

A large number of survey projects have taken place on Crete: 45 in the present reckoning, with at least 11 new projects in the last 10 years and 23 since 2000 (Fig. 10). Gkiasta (Reference Gkiasta2008) provides a catalogue of some 17 ‘landscape tradition’ survey projects in The Historiography of Landscape Research on Crete, with information also about 17 additional studies and surveys ranging from travellers’ accounts to projects in the traditions of culture history, human geography, and topography.

Fig. 10. Survey project extents in western Crete (top) and eastern Crete (bottom), with finder map showing the extent of the two maps.

In western Crete, the Rethymno Hilly Countryside Archaeological Project has investigated a 25km2 area since 2019, including surface survey, geophysics, and test excavation. The project has focused particularly on two multiperiod sites: Aï-Lias, notable mainly for its Minoan remains, and Kephala, with finds primarily from Geometric–Classical times. Recent publications of the Sphakia Survey (1987–92) are also noteworthy, including an ‘internet edition’ with photos, videos, and previous publications, and an article examining topical issues of sustainability, landscape management, and resource packages (Nixon Reference Nixon2024; Nixon et al. Reference Nixon, Price, Moody and Rackham2024). The Plakias Survey, targeting the Mesolithic and Palaeolithic landscapes of southwestern Crete, has also made major discoveries, which have become the subject of much discussion and debate concerning early seafaring in the Aegean (Strasser et al. Reference Strasser, Panagopoulou, Runnels, Murray, Thompson, Karkanas, McCoy and Wegmann2010; Cherry and Leppard Reference Cherry and Leppard2025).

Over the last two decades, several projects have taken place at and around Knossos. The most significant of these is the Knossos Urban Landscape Project (KULP; ID2900). While fieldwork began in 2005 and is not fully published, seven preliminary reports from the twelfth Cretological Conference make clear that the results are already reshaping the way we think about one of the most important centres in the Aegean, and for many periods (e.g. Whitelaw, Bredaki and Vasilakis Reference Whitelaw, Bredaki and Vasilakis2019). The combination of detailed survey data (over 300,000 sherds collected over a ca. 11km2 area) and a century’s worth of regular research and rescue excavation at the site show how disparate datasets can work together to address questions of state formation (signalling revolution over evolution in that debate), a previously unknown extensive settlement in the Early Iron Age (to accompany the dozens of excavated tombs), and a booming, expansive city in the often overlooked Classical–Roman periods. Other projects at Knossos include geophysical surveys focused on the Roman period city (ID6630) and on the Bronze Age at Gypsades (ID8570). Most recently (2019 and 2021), Kelly and O’Neill have carried out a specialized survey of aqueducts in the greater Heraklion area (ID18034). To the south, a variety of survey work has taken place in the vicinity of Phaistos (Bredaki and Lungo Reference Bredaki and Lungo2015) building upon earlier work in the Mesara (Watrous, Hadzi-Vallianou and Blitzer Reference Watrous, Hadzi-Vallianou and Blitzer2004). In the eastern part of central Crete, the Galatas Survey (ID266) was conceived as an inter-site survey, between the powerful centres of Knossos/Herakleion and Kastelli/Lyttos (Watrous et al. Reference Watrous, Buell, Kokinou, Soupios, Sarris, Beckmann, Rethemiotakis, Turner, Gallimore and Hammond2017); this project was located within the territory of a larger extensive survey of the Pediada region (ID787; Panagiotakis Reference Panagiotakis2003).

In eastern Crete, a survey of the Sissi basin took place between 2017 and 2019, covering an area of about 2.4km2 and documenting 36 sites (Terrana et al. Reference Terrana, Mouthuy, Kress, Driessen and Driessen2022), abutting an area to the west surveyed by the Malia Plain Survey (1989–present; Müller Celka, Puglisi and Bendali Reference Müller Celka, Puglisi, Bendali, Touchais, Laffineur and Rougemont2014). Survey and excavation work at Anavlochos has focused on a ridge extending from the modern settlement of Vrachasi, and revealed a 10ha settlement, 12ha necropolis, and three cult places over an overall survey area of ca. 1.5km2. With finds primarily from LM IIIC to the Early Archaic period, it is chronologically and geographically between the Minoan site of Sissi and the later Archaic poleis of Milatos and Dreros. Just north of Agios Nikolaos, the Khavania Topographical and Architectural Mapping Project (ID18054) has carried out site-based field collections and architectural mapping since 2019, revealing a significant amount of LM II pottery, a period that is generally absent at other major sites in the Mirabello Bay region (Priniatikos Pyrgos, Gournia, and Pseira). In the area of Sitea, an intensive survey has taken place at Faneromeni, which revealed eight Final Neolithic and Early Minoan sites, alongside nine modern farmsteads, with other periods for the most part absent (Papadatos and Sofianou Reference Papadatos and Sofianou2015). Recent work at Palaikastro has combined remote sensing with extensive survey to document widespread agricultural and pastoral practices in a highly structured landscape (Orengo and Knappett Reference Orengo and Knappett2018); this has been complemented by other types of landscape study, such as coastal geomorphology (Veropoulidou et al. Reference Veropoulidou, Krahtopoulou, Frederick, Orengo, Riera-Mora, Knappett and Livarda2025) and paleoenvironmental and bioarchaeological analysis of plant and animal remains (Livarda et al. Reference Livarda, Orengo, Cañellas-Boltà, Riera-Mora, Picornell-Gelabert, Tzevelekidi, Veropoulidou, Marlasca Martín and Krahtopoulou2021).

Several specialized projects in east Crete have investigated types of marginal environments that have long been neglected by surveys in Greece. The mountainous terrain of east Crete has been particularly fruitful ground for surveys on Mt Dikte and in the Zakros uplands of the Siteia Mountains (Kalantzopoulou Reference Kalantzopoulou2022; Papadatos and Kalantzopoulou Reference Papadatos, Kalantzopoulou, van Wijngaarden and Driessen2022). These projects have demonstrated the importance of combined methods of extensive survey and site documentation to reveal evidence for rural habitation, political organization, and pastoral (and other) economies. They complement the ongoing work of the Minoan Roads Project near Zakros (since 1984), which has also undertaken a recent intensive survey at Katsounaki, Xerokambos (Chrysoulaki and Vokotopoulos Reference Chrysoulaki, Vokotopoulos, Antonopoulou and Petrounakos2022). The most recent project in this tradition is the Surveying High Elevation Ecozones for Prehistory Project (SHEEP), on the eastern slopes of Mt Dikte (Kalantzopoulou Reference Kalantzopoulou2023), which overlaps with an area previously studied by Beckmann (Reference Beckmann2012) in order to provide more thorough documentation; both this and the previous work on Dikte complement recent excavations at Gaidourophas (e.g. Papadatos and Chalikias Reference Papadatos, Chalikias, Oddo and Chalikias2019). Together, these projects have demonstrated the importance of combined methods of extensive survey and site documentation to reveal evidence for rural habitation, political organization, movement, and pastoral (and other) economies.

Work in the islets of Crete has also been groundbreaking, including long-term surveys at Gavdos and Pseira (Kopaka Reference Kopaka, Karetsou, Detorakis and Kalokairinos2001; Betancourt et al. Reference Betancourt, Davaras and Hope Simpson2004; Reference Betancourt, Davaras and Hope Simpson2005), as well as more recent work on Dia (Kopaka Reference Kopaka2012), the Dionysades islets (Dragonara), and Chryssi (for summaries, see Kopaka and Kossyva Reference Kopaka, Kossyva, Betancourt, Karageorghis, Laffineur and Niemeier1999; Chalikias Reference Chalikias2013). Work on several of these islets was presented in detail at a recent conference (Eaby, Chalikias and Sofianou Reference Eaby, Chalikias and Sofianouforthcoming).

Recent projects in Crete have focused on particular sites and particular problems, in contrast to the large-scale intensive fieldwalking surveys of earlier generations. At the same time, several earlier, regional surveys have been brought to publication, creating opportunities for comparative and synthetic work across larger regions. Pollard (Reference Pollard2023) used data from the Vrokastro (Hayden Reference Hayden2005), Gournia (Watrous et al. Reference Watrous, Haggis, Nowicki, Vogeikoff-Brogan and Schultz2012), and Kavousi (Haggis Reference Haggis2005) surveys to highlight the consolidation of settlement and population centres from the Early Iron Age to the Archaic Period in the Mirabello Bay region. Erny (Reference Erny2023) used legacy data from seven surveys across the island to reveal markedly varied settlement patterns in different parts of Crete from the Geometric to Hellenistic periods; these also differed from contemporary patterns on the Greek mainland. From a methodological perspective, Drillat (Reference Drillat2024) has examined sometimes contradictory survey results from overlapping projects (the Galatas and Pediada surveys). In a synthesis of data across Crete, Spencer and Bevan (Reference Spencer and Bevan2018) use survey data to create settlement location models and examine social change across the Bronze Age. Recent work by Whitelaw (Reference Whitelaw, Relaki and Papadatos2018; Reference Whitelaw, Garcia, Orgeolet, Pomadere and Zurbach2019) also provides models of long-term, regional trends in urbanism and demography, based mainly on survey data.

Discussion and conclusions