1.1 Introduction

The French can be surprised that foreigners come to France to study ancient Greece.Footnote 1 They understand why Anglophone philosophers do so, as it is a matter of genuine national pride that ‘French theory’ conquered the world in the 1980s.Footnote 2 But relatively few French people realise that among English-speaking researchers of ancient Greece the so-called Paris school was no less influential.Footnote 3 The leading figures of this Paris-based circle of ancient historians were Jean-Pierre Vernant and Pierre Vidal-Naquet.Footnote 4 Reading their books as well as those of younger circle-members has profoundly shaped our historiography. It turned me and other budding foreign researchers of ancient Greece into the cultural historians that we are today.Footnote 5 The book of the Paris school that exerted the greatest influence on my generation was The Invention of Athens by Nicole Loraux. It was the first book-length study of the speech that democratic Athens staged for the war dead. Before this book’s publication in 1981, ancient historians had accorded little importance to the funeral oration. For them, the genre consisted only of dubious clichés. It also endorsed a pronounced cultural militarism: funeral orators claimed that war brought only benefits and sought to deny the human costs. This was at odds with the strong anti-militarism on the French left during the 1970s. In writing a book about this genre, Loraux clearly was a trailblazer. The Invention of Athens established for the first time the vital importance of this almost annual speech in the formation of Athenian self-identity. Loraux showed how each staging of it helped the Athenians to maintain the same shared civic identity for over two centuries. The Invention of Athens was also clearly different from the other books of the Paris school. At the time, Vernant and Vidal-Naquet, for example, were researching the basic structures of Greek thought.Footnote 6 What Loraux had discovered was more complex: a detailed narrative about who the Athenians were and a set of discursive practices for its maintenance.

The Invention of Athens truly was a remarkable achievement. Yet, in spite of its transformative impact, it was still far from a complete work. Loraux deliberately played down individual authorship as a topic of study, which helped her to prove that the surviving funeral speeches were part of a long-stable genre. But this meant that The Invention of Athens left unanswered important questions about each of the seven surviving examples. An even larger gap concerned intertextuality. The Invention of Athens rightly saw traces of the funeral oration right across Athenian literature, but it never systematically compared the funeral oration with other types of public speech or drama. Therefore, Loraux was unable to demonstrate whether the other literary genres of classical Athens were ever a counterweight to the funeral oration’s cultural militarism. Without such intertextuality, her ability to prove many of her bold hypotheses was limited. The principal aim of this edited volume is to complete methodically The Invention of Athens. To this end, our book dedicates a chapter to each extant funeral speech in order to answer the important questions that Loraux left unanswered. It completes the vital intertextual analysis of the genre that is missing in The Invention of Athens. In filling such gaps, our chapters also aim to reassess numerous bold arguments and claims that Loraux made in her celebrated first book. Another aim of ours is to furnish a rich analysis of war’s overall place in the culture of democratic Athens.

1.2 The Transformative Impact of Nicole Loraux

The classical Athenians claimed to be the only Greeks to honour the war dead with a funeral oration.Footnote 7 Seven examples of what does appear to be a unique Athenian genre have survived in whole or part. The most famous of them is the epitaphios logos (‘funeral speech’) attributed to Pericles from 431/0 BC.Footnote 8 We also have the actual speeches that Demosthenes delivered in 338/7 and Hyperides in 323/2. The other four examples were by authors who never intended to speak at a public funeral for the fallen. In the early fourth century, Lysias and Plato published long literary versions of a funeral oration, while Isocrates, in his first major publication, drew extensively on the genre. Several decades earlier, Gorgias, soon after arriving in Athens from Sicily, had written his own epitaphios logos. Today, there is broad agreement that the official speech was a vitally important institution for articulating how the classical Athenians thought of themselves.Footnote 9 Therefore, when they study Athenian public discourse, cultural historians now invariably put this genre on a par with forensic and deliberative oratory as well as old comedy and tragedy.Footnote 10

Such a clear consensus makes it easy to forget how the funeral oration was viewed completely differently forty or more years ago. Indeed, before 1981, ancient historians considered the genre to be of little importance.Footnote 11 As funeral orators always repeated ‘the same banalities’, theirs was ‘an untruthful genre’ that shed no light on Athenian politics.Footnote 12 Instead, the funeral oration was taken only as an example of what Aristotle came to call epideictic oratory: a display speech with no serious purpose.Footnote 13 Admittedly, the epitaphios logos of 431/0 was still regularly studied because Pericles, many ancient historians thought, had brilliantly succeeded in escaping the funeral oration’s deadening constraints.Footnote 14 But no one ever saw the need for a dedicated study of this genre as a whole.Footnote 15

Therefore, a veritable paradigm shift has occurred in our understanding of the Athenian funeral oration. In the 1970s, Nicole Loraux, against the tide, decided to study the genre. Her The Invention of Athens, published in French in 1981 and in English five years later, is almost entirely responsible for this shift. One of its most important findings concerned Pericles’ funeral speech. Loraux put beyond doubt that it was part of an oral tradition that remained stable for over a century. The epitaphios logos of Pericles had the same structure as the others and touched on the same topics.Footnote 16 It included 31 of the 38 topoi (‘commonplaces’) that the fourth-century funeral speeches shared.Footnote 17 The Invention of Athens also found that the genre had a surprising focus. As a speech in honour of combatants who had fallen in a particular year, it, predictably, praised them,Footnote 18 exhorted the living to show as much courage as they had,Footnote 19 and consoled their bereaved relatives.Footnote 20 Surprisingly, however, it directed most of its praise to the Athenians as a people.Footnote 21 Consequently, every citizen who listened to an epitaphios logos felt ‘greater, nobler and finer’ (Pl. Menex. 235b). Loraux confirmed that this praise usually consisted of a positive narrative about Athenian military history,Footnote 22 in which the Athenians were almost always victorious.Footnote 23 In fighting for the freedom or safety of others, they always waged just wars. Funeral orators characterised the Athenians in the same way for 130 years. They did so, according to Loraux, because this was how the dēmos (‘people’) continued to think of themselves.Footnote 24 Loraux really was the first ancient historian to identify such complex collective thinking. Therefore, the final important finding of The Invention of Athens was the existence itself of Athenian self-identity.

Loraux closely analysed how this epitaphic narrative operated. It basically was a series of disconnected erga, or exploits.Footnote 25 In discussing this catalogue of exploits, funeral orators always distinguished between mythical and historical erga.Footnote 26 The Invention of Athens demonstrated how each historical exploit revealed standard characteristics of the Athenians. Such exploits always showed them to be agathoi andres (‘courageous men’),Footnote 27 who surpassed all others in aretē (‘courage’).Footnote 28 Historical Athenians regularly fought for the freedom of other Greeks or for justice.Footnote 29 Several of their erga concerned the protection of persecuted weak states.Footnote 30 This recital of erga gave pride of place to the Persian Wars of 490 and 480–79.Footnote 31 These wars, after all, included several great victories, in which the Athenians had demonstrated all their ‘national’ characteristics.

Loraux was clear-eyed about how the catalogue of exploits distorted history. Because the dēmos believed that a defeat was usually due to deilia (‘cowardice’),Footnote 32 funeral orators avoided mentioning defeats because they would call into question the aretē that the dēmos claimed.Footnote 33 When this was not possible, they turned a defeat into a temporary setback.Footnote 34 Alternatively, they attributed it to, for example, the will of the gods or the mistakes of other people.Footnote 35 A second distortion was the catalogue’s Athenocentrism.Footnote 36 Like the other Greeks, the Athenians fought as part of a military coalition most of the time.Footnote 37 Funeral orators often twisted such joint military efforts into purely Athenian ones.Footnote 38 When such a distortion would be too farfetched, they made Athens the undisputed military leader.Footnote 39

The classical Greeks often used myth to justify a claim about themselves.Footnote 40 Loraux rightly saw that the mythical erga had this function in the epitaphic narrative. The extant epitaphioi logoi (‘funeral speeches’) had in common three standard myths. In the first, the Athenians repelled the invasion of Greece by the Amazons (e.g. Dem. 60.8; Lys. 2.4–6; Pl. Menex. 239b). Loraux recognised the parallels between this ‘barbarian’ people and the funeral oration’s Persians.Footnote 41 This myth clearly supported what the genre claimed about Athens in the Persian Wars. The second myth concerned the Thebans’ refusal to let their defeated enemy, the Argives, bury their war dead (e.g. Dem. 60.8–9; Lys. 2.7–10; Pl. Menex. 239b). Because the classical Greeks believed such a burial to be a divine nomos (‘custom’ or ‘unwritten law’),Footnote 42 this myth helped to justify the claim that Athens always fought for justice. The final myth had the Athenians protecting the children of Heracles, who had come to Athens as refugees (e.g. Dem. 60.8; Lys. 2.11–16; Pl. Menex. 239b). In order to do so, they had to defeat an enormous coalition army from the Peloponnese. This myth lent support to, among other things, the epitaphic characterisation of the Athenians as the protectors of the persecuted and weak.

The Invention of Athens put beyond doubt the genre’s vital importance in maintaining Athenian self-identity. The premature death of fellow citizens in battle had the potential to call into question core beliefs that the dēmos held.Footnote 43 It could lead to dangerous political opposition during a war. Loraux plausibly suggested that a major function of the funeral oration was to affirm what the dēmos believed in the face of such potential negative responses.Footnote 44 What made it more effective for this discursive maintenance was its frequency.Footnote 45 Athens staged a public funeral for the war dead each year when there were Athenian casualties.Footnote 46 Because it went to war in two out of three years in the fifth century and even more frequently in the fourth century,Footnote 47 an epitaphios logos would have regularly been an annual event. The genre also furnished the most detailed account of Athenian history to which the dēmos had access.Footnote 48 The other genres of public oratory and drama focussed much less on self-identity and the past. This was due to their different primary functions. Politicians and litigants wanted to win a political debate or a legal case.Footnote 49 They mentioned a core belief or a military campaign only if it helped them to do so.Footnote 50 Since the poets of old comedy had to raise as many laughs as possible, their comedies were rarely lessons in civic education. The tragic poets set the majority of their plays outside Athens,Footnote 51 which meant that it was less common for them to focus explicitly on Athenian self-identity.

In spite of their different functions, these literary genres are still all good evidence for how non-elite Athenians viewed themselves and their world more generally. Although dramatists, politicians and litigants belonged almost always to the elite, their audiences were predominantly non-elite.Footnote 52 In dramatic agōnes (‘contests’), state-appointed judges might have formally voted on who the winner would be,Footnote 53 but they clearly took their lead from how the non-elite theatregoers had responded to each play (e.g. Dem. 18.265, 19.33, 21.226). The result was that comic and tragic poets needed to reproduce the non-elite viewpoint (e.g. Pl. Leg. 659a–c, 700a–1b). Politicians and litigants had to do this even more because the outcomes of their agōnes depended on the actual votes of their audiences (e.g. Pl. Resp. 493d). By contrast, funeral orators were not competing for votes in a formal agōn (‘contest’).Footnote 54 Nevertheless, Loraux was absolutely right to assume that they articulated no less how the dēmos generally thought. After all, the democratic council chose a funeral orator from among the leading politicians.Footnote 55 Such orators knew that they had to meet the expectations of a large crowd of mourners.Footnote 56

The Invention of Athens played a major role in the cultural turn in Classical Studies. As a result, it can be forgotten that Loraux lacked the theoretical tools that contemporary cultural historians take for granted.Footnote 57 Today, discourse analysis and the studies of oral tradition and social memory are well established. This was not the case when Loraux wrote The Invention of Athens. Consequently, her discovery, in the funeral oration, of a complex narrative of self-identity was a remarkable achievement. Vincent Azoulay and Paulin Ismard (Chapter 3) remind us that Marxism was one of the few tools that Loraux had at her disposal. In capitalism, Karl Marx argued, the bourgeoisie had created an ideology to obscure their economic exploitation of the working class.Footnote 58 In his eyes, ideology lacked any independence from economics.Footnote 59 Because it was only an illusory reflection of this reality, studying it was of little importance.Footnote 60 Instead, for Marx, the economic base was the key for understanding capitalist society. Azoulay and Ismard rightly point out that The Invention of Athens explicitly rejected Marx’s traditional argument.Footnote 61 In its conclusion, Loraux argued that ‘an institutional illusion is still a fact’.Footnote 62 Athenian self-identity, according to her, was thus ‘an integral part of Athenian political practice’. It mediated the relations that the Athenians had with reality and was independent of the economic base. Loraux reinforced this rejection by choosing, not ideology, but l’imaginaire (‘the imaginary’) for describing ‘all figures in which a society apprehends its identity’. Loraux made abundantly clear that she had borrowed this term from the exiled Greek, Cornelius Castoriadis,Footnote 63 who, with Claude Lefort, had founded a left-wing anti-Stalinist intellectual circle (Figure 1.1).Footnote 64 Among their criticisms of Marx was his unwarranted devaluing of culture.Footnote 65

Figure 1.1 Nicole Loraux speaks at a conference in Montrouge (Paris) in 1987, along with, from left to right, Claude Lefort, Louis Dumont and François Furet.

The surprise of Azoulay and Ismard’s chapter is that Loraux’s relationship to Marxism was more nuanced than her conclusion suggests. Indeed, in a later abridged edition of The Invention of Athens for French readers, Loraux exchanged the imaginary for the Marxist concept of ideology that she had first encountered in the 1970s.Footnote 66 It is tempting to interpret this exchange simply as her combative response to Castoriadis’ public criticism of her use of his new term.Footnote 67 Yet, the chapter of Azoulay and Ismard puts beyond doubt that a version of Marxism was always a critical tool for her. The famous re-reading of Marx by Louis Althusser clearly echoes throughout The Invention of Athens.Footnote 68 Certainly, Althusser, as a longstanding Marxist, held that ideology was more or less about the economic base because it articulated for individuals what economic roles they were supposed to perform. Nevertheless, he also went beyond Marx by seeing ideology as largely independent from economics and as a key phenomenon for understanding any society.Footnote 69 Loraux, of course, extended Althusser’s re-reading by disconnecting ideology entirely from the economic base and making it a product, not of an economic class, but of the political community as a whole.Footnote 70 Even here, however, Azoulay and Ismard conclude, there were still echoes of Marx, for Loraux had taken over both extensions from the many Marxism-inspired studies of classical Greece in the 1970s.Footnote 71 Cultural historians today do not always acknowledge their debts to Marxism.Footnote 72 The Invention of Athens shows us how important it was as a tool for their pioneering figures.

1.3 The Public Honours for the War Dead

Thucydides set the scene for Pericles’ famous funeral speech of 431/0 by describing the public funeral for the war dead (2.34). Rich as his description was, it actually failed to mention three timai (‘honours’) that classical Athens granted them.Footnote 73 His chapter 2.34 also did not provide sufficient background for measuring how exceptional these honours were. The Invention of Athens was strong on filling this chapter’s gaps.Footnote 74 By the late 430s, the Athenians had for a long time brought home the bones of their war dead, whom they had cremated on or near the battlefield.Footnote 75 The first stage of the public burial was the prothesis (‘display’) of these bones for two days in cypress-wood coffins.Footnote 76 Here there was one coffin for each of the ten Cleisthenic phulai, or tribes (Thuc. 2.34.2–3). The bereaved deposited offerings next to the coffin that contained, supposedly, the bones of their loved one.Footnote 77 On the third day, an ekphora (‘funeral procession’) escorted these ten coffins to the vicinity of the public tombs. These tombs were located in the Ceramicus – the potters’ district, which was, according to Thucydides, ‘the most beautiful suburb of the city’ (5; cf. Ar. Av. 395–9). That the Athenians used wagons for this ekphora points to it covering a reasonable distance, which suggests that the prothesis probably took place in the Athenian agora (‘civic centre’).Footnote 78 Loraux brought to the fore what was exceptional in these first stages of the public funeral. In classical Athens, it was illegal for a family to stage a prothesis of more than a day.Footnote 79 The longer one for the war dead helped to make the public funeral itself a substantial timē (‘honour’). Loraux plausibly proposed that the armed forces played a large part in this ekphora.Footnote 80 She was the first to appreciate the significance of the cypress wood of the coffins.Footnote 81 The palaces of epic poetry were built out of this timber (e.g. Hom Od. 17.340), while the classical Greeks considered cypress to be precious, like silver and gold, and a guarantor of deathless memory (e.g. Pind. Pyth. 5.39; Plut. Vit. Per. 12.6).

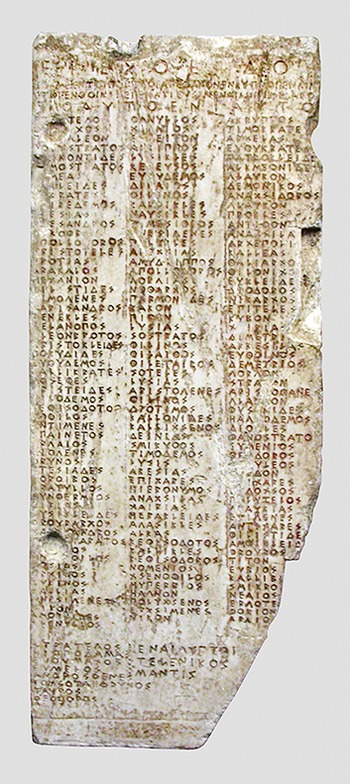

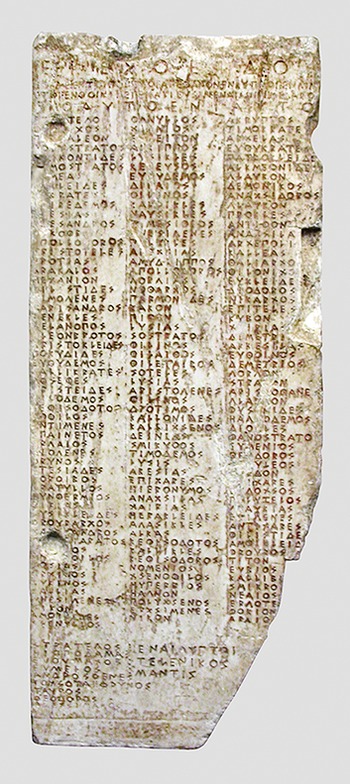

The first timē that Thucydides failed to mention was the public tomb before which the funeral orator spoke. Such a burial place took the form of a tumulus or a walled rectangular enclosure.Footnote 82 The most conspicuous constituent of it was a list of the year’s casualties that was organised by tribe.Footnote 83 This list could be a line of ten individual slabs or a continuous wall with recesses between the phulai (Figure 1.2). A casualty list was often two metres in height and several metres in length.Footnote 84 Plato’s Socrates understandably described this burial as ‘beautiful and magnificent’ (Menex. 234c). In the early years of Athenian democracy, rich Athenians abandoned the archaic practice of building lavish private tombs.Footnote 85 As a group, they began to provide such tombs for their relatives again only in the 430s. Because the rectangular ones that they now built cost thousands of drachmas,Footnote 86 Plato’s Socrates was right to assert that a penēs (‘poor man’) who had died in battle gained a tomb for which his family could never have paid (Menex. 234c). But a public tomb for the fallen was also always grander than elite private ones (Xen. Hell. 2.4.17), as it had to accommodate ten tribal coffins and a long list of casualties.

Figure 1.2 The list of the war dead from one Cleisthenic tribe that was part of a collective tomb of 460 BC or thereabouts. Paris, Louvre Museum, inv. no. MA 863 (IG i3 1147).

Such a tomb could also include a figural relief. Loraux was not alone in overestimating the commonness of these reliefs.Footnote 87 Indeed, only two of the many casualty lists that survive from the fifth century had such decoration.Footnote 88 The earliest known one was the list of the war dead from 433/2. Although the relief itself is lost, a drawing of it by L. F. S Fauvel shows three hoplites fighting.Footnote 89 The fragment of the next relief in date is today in Oxford.Footnote 90 Coming from the second half of the fifth century, it depicts a fallen hoplite who is being protected by another. The final known relief is on the casualty list of 394/3 (Figure 18.2).Footnote 91 This well-preserved relief has a horseman attacking a fallen hoplite, whom, again, another hoplite tries to protect. These three reliefs were not depictions of outright military victory.Footnote 92 Instead, they focussed on ‘the struggles, dangers and risks of war’.Footnote 93 In doing so, they depicted the fallen bearing the kindunoi (‘dangers’) that would kill them.

By contrast, it was much more common for a casualty list to include an inscribed poem.Footnote 94 Such epigrams drew heavily on epic poetry in their praise of the war dead.Footnote 95 The three recorded epigrams from 433/2 make a good example. The first praised the fallen for revealing aretē and acquiring a mnēma (‘memorial’) of their military success (IG i3 1179.3–5), while the second noted how the enemy’s cowardice had resulted in their slaughter or retreat (8–9). The final epigram reinforced what the Athenian dead had gained. By dying in battle, they had put their aretē beyond doubt and created eukleia (‘glory’) for the state (12–13). We find a comparable cluster of ideas in the epigram for those who fell in 447/6 (IG i3 1162.45–8):

These men perished by the Hellespont striving for the splendour of youthfulness. They gave their fatherland glory as their enemies wailed for those who had endured a summer of war. They established for themselves a deathless memory of their aretē.

Funeral orators expanded upon such ideas about this ‘most becoming (euprepestatē)’ or ‘most beautiful (kallistē)’ death.Footnote 96 They explained that falling in battle for the state or for public ideals resulted in deathless praise and eukleia.Footnote 97 From such a death the war dead secured athanatos mnēmē (‘deathless memory’) of their courage (Hyper. 6.27–30; Lys. 2.79–81). This mnēmē – the orators added – extended to their youthfulness, as, by dying young, they had escaped the decline of old age (Dem. 60.32–3; Hyper. 6.42–3; Lys. 2.78–9).

Thucydides also failed to mention the two timai that came after the funeral oration. The first of them were the agōnes (‘contests’) that Athens staged in honour of all war dead each year.Footnote 98 The annual sacrifices for them were presumably made as part of this competitive festival.Footnote 99 These agōnes in athletics, music and horsemanship were extensive enough to attract foreign competitors.Footnote 100 The first evidence of them are a hydria and two lebētes.Footnote 101 These bronze vessels range in date from soon after the Second Persian War to the second half of the fifth century. The inscription on each confirms that it was a prize from the games in honour of the Athenian war dead (IG i3 523–5). These contests clearly continued into the fourth century (e.g. Dem. 60.13; Lys. 2.80). In classical times, the Greeks staged public agōnes only for gods and demi-gods.Footnote 102 Therefore, the staging of them for the war dead points to the dēmos considering them to be heroes.Footnote 103 Loraux rightly saw corroboration of this heroisation in epitaphioi logoi.Footnote 104 Lysias, like Demosthenes (60.36), had the war dead receiving ‘the same honours as the gods’ (Lys. 2.80; cf. Isoc. 4.84). In his non-extant funeral speech of 440/39, Pericles appears to have gone further, for he argued, according to Stesimbrotus, that the war dead’s immortality was evident not only in their cultic timai but also in the agatha (‘benefits’) that they continued to give.Footnote 105 Of course, it was in the hope of such supernatural agatha that the Greeks worshipped their demi-gods.Footnote 106 The final timē on which Thucydides 2.34 was silent was the state’s material support of the war dead’s families.Footnote 107 For their sons, this support culminated in a civic ceremony at the annual festival of the City Dionysia, when they turned eighteen years old. Before the tragic agōn (‘contest’) started, the state publicly gave the sons the gifts of a hoplite-panoply and proedria (‘front-row seating’).Footnote 108

Some of the honours that the dēmos granted the war dead were derived from epic poetry. Loraux began comparing these honours and the epic ones for fallen warriors in The Invention of Athens.Footnote 109 A year after finishing the writing of her first book, she completed this comparison for what would become a celebrated Franco-Italian conference on death in ancient societies.Footnote 110 Her chapter in our edited volume (Chapter 2) is the first English translation of her famous conference paper from 1977. It leaves us in no doubt that what the funeral orators described as ‘the most beautiful death’ went back to Homer.Footnote 111 In his Iliad, a hero’s death in battle proved for all time his aretē and gave him deathless memory of his glory and youthfulness.Footnote 112 What guaranteed all this was his mnēma, which triggered the memories of passers-by, and the recounting of klea andrōn, that is, his glorious exploits, in a poet’s song.Footnote 113 Loraux’s chapter explores how the Athenian dēmos copied – or more often transformed – this epic model. Homer gave his ‘beautiful death’ only to the heroes, such as Hector and Patroclus, who were elite leaders.Footnote 114 In the Iliad, non-elite soldiers who had fallen in battle were granted much less, as they were cremated and buried in a mass grave without any ceremony.Footnote 115 It was assumed that in Hades they would join only the nōnumoi (‘the nameless’), that is, the masses that were deprived of any eternal glory. Among the important transformations that the Athenian dēmos made to this epic model was their granting of the ‘beautiful death’ of the elite heroes to all fellow citizens, regardless of their military rank and social class.

Loraux’s chapter also boldly claims that democratic egalitarianism was the main organising principle of the Athenian public funeral.Footnote 116 Certainly, egalitarianism was among the strongest principles of Athenian democracy.Footnote 117 For his part, Euripides called Athens an isopsēphos polis (‘equal-voting city’), in which the rich and the poor ruled ‘equally’, enjoying equality in public speech as well as the law-courts (Supp. 353, 407–8, 430–41). Greek democrats justified this equal granting of political and legal timai on the grounds that all citizens shared in vital respects an equal nature.Footnote 118 For Loraux and others, this egalitarianism could be seen most clearly in the Athenian casualty lists, as they gave the same space to the name of every combatant.Footnote 119 Loraux saw it too in how funeral orators narrated military history: they almost always attributed Athenian victories anonymously to ‘the ancestors’, ‘the fathers’, ‘the Athenians’ or those being buried.Footnote 120 Such anonymity gave equal responsibility for military success to every combatant.Footnote 121 It came at the expense of elite generals, who, in other public contexts, continued to be honoured individually for such military success.Footnote 122 Literary evidence backs up this bold claim of Loraux (e.g. Dem. 18.208). In a tragic fragment from the 420s, for example, mythical Athenians who die in war were collectively given a koinos (‘common’) tomb and isē (‘equal’) glory.Footnote 123 The classical Athenians regularly employed koinos and compound words with isos to describe or to justify democratic egalitarianism.Footnote 124

Loraux also understood well that that the public funeral marginalised the normally central role of families.Footnote 125 In classical Athens, relatives were still obliged to bury their dead and to look after their graves.Footnote 126 Therefore, by fulfilling this obligation for the fallen, the Athenian state was intruding deeply into private affairs. Those who felt this intrusion most acutely were Attic women because this traditional mortuary obligation mainly fell on them.Footnote 127 It was they who washed and clothed the dead, mourned for them at the prothesis, played a conspicuous part in funeral processions and took care of their graves.Footnote 128 Yet, in the state’s burial of the war dead, there were no longer bodies for them to care for. Now they could leave grave offerings only next to a tribal coffin or at the public burial itself. The funeral orators did acknowledge the penthos (‘mourning’) and the lupē (‘pain’) of the bereaved.Footnote 129 Nevertheless, they also instructed them to suppress these feelings by remembering instead the ‘beautiful death’ of their men.Footnote 130 Indeed, the public funeral generally strove to ignore the private lives of the fallen.Footnote 131 By omitting their patronymics and demotics, the casualty lists had an important role in this.Footnote 132 But so did the funeral oration in its focus on their death in battle instead of what they had done in life.Footnote 133 In praising all the dead equally, this speech also erased the social differences between them.Footnote 134

Nathan Arrington (Chapter 4) studies the painted pots that fifth-century families purchased as grave offerings for the war dead. His chapter shows how such purchases helped the bereaved to resist their marginalisation by the state. Loraux categorically refused to study such private art. In part, this was due to her argument about the transformation of the ‘beautiful death’.Footnote 135 In archaic times, the beauty of the fallen elite soldier resided in his sōma (‘body’) at the pre-burial display. In transferring this beauty to his decision to die, the Athenian dēmos, Loraux argued, no longer wanted to represent the war dead’s bodies. However, Arrington draws our attention to the many pictures of the war dead on red-figure loutrophoroi and white-ground lēkuthoi. As both these types of Athenian pot were employed in readying a body for the prothesis, they were common grave offerings. Loutrophoroi often had paintings of combat or of a soldier leaving home or standing beside his grave.Footnote 136 Sometimes they even depicted a casualty list.Footnote 137 Such ‘warrior’ loutrophoroi were among the grave goods in the one public tomb for the war dead that has been excavated.Footnote 138 The iconography of many lēkuthoi was no less tightly linked to the fallen.Footnote 139 Because potters generally needed to produce what their customers wanted, these paintings let us see how families thought privately about their loss.Footnote 140

Certainly, they were proud of the death of their men in battle because this iconography always styled the dead as soldiers. Importantly, though, Arrington puts beyond doubt that it also reveals other thoughts that harmonised far less with public discourse. For example, loutrophoroi frequently depicted elite private tombs that were well tended by females. While all of this was no longer possible, relatives, it seems, still imagined their fulfilling of the traditional obligation to their dead. Families, clearly, also wanted to remember what their dead relatives had done in life, as pots often depicted them as, for example, men who had practised hunting or horsemanship. Because such activities were exclusive elite pursuits,Footnote 141 these images show a rejection of the epitaphic idea that there had been no social differences among the war dead. In addition, the soldiers on these loutrophoroi and lēkuthoi were invariably physically fit and handsome,Footnote 142 suggesting that the archaic idea of the ‘beautiful dead’ still had wide currency. These pots, finally, poignantly depicted the intense grief that family members continued to feel years after the premature loss of their loved ones.Footnote 143 For them, suppressing their direct experience of war’s personal cost was far harder than the funeral oration glibly suggested.

1.4 Dating the Honours for the Fallen

The Invention of Athens furnished a new dating of the epitaphios logos. Pericles himself confirmed that this timē was a late addition to the public funeral (Thuc. 2.35.1). Postclassical authors dated this addition to the immediate aftermath of the Second Persian War.Footnote 144 It is still quite common to accept their dating,Footnote 145 but Loraux argued that content in the genre could not be so old.Footnote 146 The standard myth about Heracles’ children is a good example (e.g. Dem. 60.8; Lys. 2.11–16; Pl. Menex. 239b). Among other things, it clearly supported a hostile stance towards Sparta. Eurystheus, after all, had invaded Attica with a coalition army from the Peloponnese. Loraux is surely right to date this myth to several years after the decisive rupture between Athens and Sparta in 462/1 (Thuc. 1.102). The same applies to autochthony, which is another standard topic in funeral speeches.Footnote 147 Athenian thinking about their indigenous origin was fully elaborated only mid-century.Footnote 148 Therefore, the funeral oration in the form that has survived was probably added to the public funeral only in the 450s. This suggests that it was, in fact, the last timē that fifth-century Athenians added to the extensive group of honours that they granted their war dead.

Loraux’s downdating of the funeral speech initially met with wide acceptance.Footnote 149 It has an important consequence for our understanding of the epitaphic genre. There are clear antecedents, well before the 450s, for what we find in the funeral oration. For example, in his Persians of 471/0, Aeschylus reduced the Persian Wars to the naval battle of Salamis, which he characterised as a purely Athenian victory.Footnote 150 Such Athenocentrism would become a hallmark of the epitaphios logos. Another hallmark was the treating of Athenian military history as a catalogue of mythical and historical erga. From the early fifth century, monuments celebrating military victories in the Athenian agora already had simple versions of such a catalogue (e.g. Aeschin. 3.183–5). For instance, the painted colonnade displayed side-by-side paintings of the mythical victories at Troy and against the Amazons as well as historical ones at Marathon and Oenoe (Figure 15.1).Footnote 151 It is true that the funeral oration would become vitally important for the maintenance of civic self-identity from the mid-fifth century. Nevertheless, important elements of this imaginary had already been elaborated in other forums of Athenian public discourse decades earlier.

Thucydides described the public burial itself as a patrios nomos, or ancestral custom (2.34.1; cf. Lys. 2.81), which implied that it was old and stable. His chapter 2.34 also claimed that Athens had always buried the war dead in the dēmosion sēma, or public cemetery (Figure 1.3). It described those who died at Marathon as the one exception. Because of their exceptional aretē, Thucydides claimed, they had been honoured with a public tomb on the battlefield. Certainly, Thucydides was right to see this custom as old because we will see that burying the war dead at public expense dated back to 507/6. Nevertheless, Thucydides still ‘made a blunder’ in his often-quoted chapter.Footnote 152 The war dead of 490/89 were far from exceptional: the Athenians who died at Salamis and Plataea, for example, were buried just as closely to where they had fallen.Footnote 153 Indeed, the dēmos decided to move such burials to the Ceramicus permanently only in the 460s.Footnote 154 Before this decision, they generally buried their war dead on or near the battlefield.Footnote 155 The timai for the war dead were also not stable. It is true that even the earliest public burials could have an epigram or a tribal list of casualties.Footnote 156 However, the games for the war dead are attested only after the Second Persian War. Loraux convincingly argued that the funeral oration was a much later addition. This means that the dēmos added or modified timai for their fallen for well over fifty years.

Figure 1.3 Tombs in the dēmosion sēma (‘public cemetery’) in the Ceramicus.

The Invention of Athens certainly recognised that the public funeral of the late 430s had emerged out of a decades-long process.Footnote 157 But Loraux was wrong to infer from this that the nomos lacked ‘a definitive date of birth’.Footnote 158 The democratic revolution of 508/7 quickly transformed Athenian warmaking. The public burial of the war dead mirrored this transformation and could even have been one of the reforms of Cleisthenes himself.Footnote 159 Before Athenian democracy, most soldiers belonged to the elite, while Athenian leaders usually initiated wars on their own initiative.Footnote 160 In archaic Athens, therefore, polemos (‘war’) was by and large a private elite activity. The treatment of the war dead reflected this situation: it was rich families that privately buried those of their members who had died in war. Many pots from sixth-century Athens depicted the return of the bodies of dead soldiers to these families.Footnote 161 The tombs that elite Athenians built at home often depicted the dead as soldiers.Footnote 162 The epigrams on such tombs drew heavily on Homer’s idea of ‘the beautiful death’.Footnote 163

In 508/7, the dēmos rose up against an elite leader who wanted to be Athens’ new tyrant.Footnote 164 They had had enough of the internal struggles of their elite and now demanded the leading role in politics.Footnote 165 Cleisthenes quickly realised this popular demand: he made the assembly and a new democratic council the final arbiters of public actions and laws.Footnote 166 Although it took another fifty years for Athenian democracy to be fully consolidated, it was still the political reforms of Cleisthenes that had put the dēmos in charge and made possible such consolidation. Therefore, these reforms are often rightly seen as the true beginning of Athenian dēmokratia.Footnote 167

It is noted much less often that Cleisthenes also proposed military reforms.Footnote 168 In 508/7, neighbouring states were in fact preparing to invade Attica.Footnote 169 Archaic Athenians had been particularly inept at stopping such invasions.Footnote 170 Cleisthenes created a new public army of hoplites and the first-ever effective mechanism for mobilising combatants.Footnote 171 The dēmos also quickly assumed the sole responsibility for foreign affairs (e.g. Hdt. 5.66, 73, 96–7). Classical-period writers recognised that Cleisthenes had made Athens much stronger militarily.Footnote 172 Certainly, his military reforms immediately helped the Athenians to perform much better in war: in 507/6, the new public army of Athenian hoplites defeated those of Chalcis and Boeotia in back-to-back battles (Hdt. 5.74–7). Polemos was now a public activity, which was wide open to non-elite participants. The treatment of those who fell in these first battles reflected this transformation. The dēmos agreed to bury all of them ‘at public expense (dēmosiai)’.Footnote 173 That the epigram on their battlefield tomb explicitly noted this significant change points to it being a conscious decision.Footnote 174 Therefore, it appears that the new collective burial of the war dead had been introduced in part to legitimise the new popular regime.Footnote 175

1.5 The Timeliness of the Historical Funeral Speeches

Loraux rightly saw that a major function of the funeral oration was to reassure the dēmos. In the face of premature deaths and military setbacks, each speaker sought to convince them that they remained the same people. Depicting the most recent war as another example of their virtuous warmaking greatly helped him to do so.Footnote 176 The Invention of Athens clearly showed how funeral speeches twisted erga in order to preserve such a story. But it never explained what motivated the speakers to assimilate the often-unsettling present into the epitaphic narrative. The main motivation probably came from the strong personal interest that each funeral orator had in the actual immediate internal politics. However, Loraux repeatedly denied that the genre ever engaged with contemporary internal politics.Footnote 177 For her, an official speech seeking to foster unity could exhibit only timelessness. Nevertheless, the three historical speeches that survive call her assumption into question. Pericles, Demosthenes and Hyperides were the main proponents of the wars in which those being buried had died. Pericles faced ongoing criticism of his war, while Demosthenes had been the politician most responsible for a crushing defeat. Although going well in 323/2, Hyperides’ new war against the Macedonians had been for years a contentious proposal. This means that their fitting of the current war into the epitaphic tradition was not a simple act of patriotism. They were also defending their original proposals and discouraging further public criticism.Footnote 178 That they saw the public funeral for the war dead as an important opportunity to achieve this goal proves again the genre’s central role in Athenian public discourse. Of course, it was the boulē (‘council’) that selected leading politicians to speak in honour of the war dead. It appears that councillors often chose the one that had the greatest personal motivation for putting a positive ‘spin’ on the most recent war.Footnote 179 In their spins, we will see, these three speakers omitted or minimised the catalogue of erga. This suggests that a funeral orator had a greater freedom in his treatment of the genre’s stock topics than Loraux thought.Footnote 180 Since antiquity, there has been a debate about the authorship of the epitaphios logos of 431/0. This speech’s clear timeliness strengthens the case that Pericles rather than Thucydides was the actual author.

Traditionally, the extant funeral speech of Pericles was viewed as superior to the other epitaphioi logoi and so rarely compared to them. Among the most important findings of The Invention of Athens was that his speech was an integral part of a longstanding tradition. Yet, in making her strong case for this, Loraux deliberately neglected three fundamental questions about this specific epitaphios logos. Answering these questions is the goal of Bernd Steinbock’s contribution to our edited volume (Chapter 5). The first question is whether Pericles or Thucydides was the real author. Loraux strongly sided with those who primarily saw it as Periclean.Footnote 181 However, she felt no need to make an equally strong case for his authorship. Her best argument was the speech’s inclusion of epitaphic topoi.Footnote 182 The weakness here is evident in the two other examples to which this epitaphios logos was closest in date: Lysias and Plato included no fewer commonplaces in theirs, but they never intended to speak at a public funeral for the war dead.Footnote 183 Since many a writer in classical Athens, it seems, could pen a decent funeral speech, Thucydides could easily have put one together years afterwards.Footnote 184 The second fundamental question is why Pericles’ epitaphios logos differed so much from what Lysias and Plato would write. They spent over half of their speeches cataloguing military erga in mythical and historical times,Footnote 185 whereas Pericles skipped this catalogue entirely (Thuc. 2.36.2–4).

Steinbock finds answers to these two questions in the timeliness of this specific funeral speech. His chapter demonstrates that Pericles’ epitaphios logos was part of his careful management of an immediate political crisis. Months earlier, this politician had convinced the dēmos to abandon Attica in the face of Sparta’s anticipated invasion (Thuc. 2.13–14). When, however, they saw their khōra (‘countryside’) being ravaged, they grew angry with him, demanding to be led out to fight.Footnote 186 Nevertheless, fighting remained much too dangerous because Sparta’s coalition army was several times larger. Therefore, Pericles was forced to manage their anger as carefully as he could (2.22.1–2). It is clear that this management extended into the war’s first public funeral. The funeral oration’s catalogue included standard erga in which the Athenians had defeated invaders with much larger armies (e.g. Lys. 2.4–6, 11–17, 20–7). Because rehearsing them now ran the risk of reviving the popular clamour to fight, Pericles replaced the catalogue with a eulogy of Athenian democracy.Footnote 187 While brief praise of dēmokratia was a standard topic of the genre, Pericles described it in much more detail than the other funeral orators did.Footnote 188 He showed how it had taught the dēmos not just courage but also other characteristics that supported their military success.Footnote 189 This epitaphios logos, it is clear, is not a generic example that Thucydides put together years afterwards. Steinbock is surely right that its close fit with the internal politics of 431/0 points strongly to Periclean authorship. This timeliness also explains why this example lacked a catalogue of exploits.

In general, Thucydides, as a historian, criticised the version of Athenian history that funeral orators carefully maintained.Footnote 190 In their catalogues of exploits, for example, Athens never changed: it had always been Greece’s most powerful state.Footnote 191 In his book 1, Thucydides directly challenged this account by arguing that other states, in mythical times, had been more powerful, with Athens rising to the top only after the Second Persian War.Footnote 192 Therefore, the third fundamental question about Pericles’ funeral speech is why Thucydides, who was a critic of the epitaphic genre, included it at all. Steinbock’s answer is that he shared the interest that Pericles had displayed in democracy’s impact on military affairs. Elsewhere in book 1, Thucydides reconstructed the debate about starting the Peloponnesian War that the Spartans had had with their allies. In this debate, the Corinthians compared the ‘national’ characteristics of the two sides.Footnote 193 The Athenians, they argued, were innovative and courageous risk-takers, who were selfless (Thuc. 1.70.1–6). The Spartans, according to them, were, by contrast, slow, risk-averse and selfish (71.1–3). In books 3 and 4, Thucydides illustrated how these different characteristics had resulted in Athenian military success in the war’s first phase.Footnote 194 His Corinthians, of course, saw such characteristics as innate (Thuc. 1.70.9). By putting Pericles’ epitaphios logos in book 2, Thucydides was instead suggesting that the Athenians had actually learnt these characteristics from being socialised in their democracy. Including this epitaphios logos, Steinbock concludes, did not undermine his historical revisionism, since Pericles had, helpfully for Thucydides, skipped the genre’s traditional account of Athenian history.

In his epitaphios logos, Demosthenes exhibited as much timeliness as Pericles had. Nevertheless, the immediate internal politics of 338/7 that he was trying to get under control were even more difficult than those of 431/0. The Athenians had lost a thousand hoplites in the recent battle against Philip II.Footnote 195 With the defeat at Chaeronea, their decades-long independence in foreign affairs had come to a shocking end.Footnote 196 In the months that followed, the dēmos struggled to make sense of this reversal. Out of anger, they were lashing out at political leaders whom they thought to be the most responsible for the disaster.Footnote 197 As he rose to deliver his funeral speech, Demosthenes knew that he was one of their targets because fighting Philip II had more or less been his failed policy.Footnote 198 Leonhard Burckhardt (Chapter 6) captures the spin that Demosthenes put on this crushing defeat. This politician argued that the Athenians had fought at Chaeronea for the sake of the freedom of the Greeks (e.g. Dem. 60.18, 23). He reminded the dēmos that they, as a people, had always done this (e.g. 10–11). In choosing his policy, therefore, the war dead had acted consistently with the ‘national’ character of the Athenians. Burckhardt shows how this spin made the defeat meaningful and neatly justified Demosthenes’ failed policy: it had been chosen by the ‘courageous men’ who were being buried because it perfectly matched traditional Athenian characteristics.Footnote 199

It is true that making the most recent war another instance of Athenian aretē was a conventional manoeuvre. In general, Demosthenes rehearsed as many of the genre’s topoi as possible. Yet, as Burckhardt shows, his epitaphios logos also departed from convention for the sake of making his spin persuasive. The first departure concerned the catalogue of exploits. For Demosthenes, this catalogue was a serious problem because it was in essence a list of victories, against which Chaeronea looked really terrible.Footnote 200 In 338/7, unfortunately, Demosthenes could not skip the catalogue, as Pericles had done, because his spin relied heavily on the state’s past military record. Instead, Demosthenes made his catalogue as brief as possible (60.8–12), which explains the striking shortness of his epitaphios logos overall,Footnote 201 and why, with an interlude (13–14), he separated the catalogue, as best as he could, from Chaeronea. In itself, his description of this defeat was another departure, for funeral orators were loath to mention a defeat because, in the eyes of the dēmos, it was usually considered a result of cowardice, which was incompatible with Athenian aretē. Again, though, for Demosthenes the current politics ruled out such silence. He could only put the defeat in as good a light as possible. His funeral speech thus attributed it to divine will and rightly pointed out that the war dead had proven their aretē by fighting to the death (e.g. 19–21). His epitaphios logos added that they had, in a sense, ‘saved’ the state because their ferocious fighting had dissuaded Philip from invading Attica itself (20).

Demosthenes’ third departure was his description of how the fallen had taken inspiration from the eponymous demi-gods of their tribes (27–31). No other epitaphios logos ever discussed such tribal mythology.Footnote 202 The standard explanation is that this was a clumsy attempt to distract the mourners from the defeat.Footnote 203 Burckhardt argues that Demosthenes was doing a great deal more.Footnote 204 The myths that he chose were primarily about self-sacrifices that had saved Athens. Therefore, in introducing them, Demosthenes was suggesting that the self-sacrifice for the safety of the state made by the fallen of 338/7 was as much a part of the Athenian tradition as self-sacrifice for victory. It is clear that Demosthenes’ spin was highly persuasive: the dēmos quickly honoured him as a benefactor and continued to think of Chaeronea in his terms.Footnote 205 Therefore, a timely epitaphios logos had significantly assisted him, as it had Pericles, in regaining control during a political crisis.

Loraux argued that Hyperides 6 was not a part of the epitaphic tradition.Footnote 206 For her, this funeral speech was a ‘subversion’ that lacked ‘fidelity’ to the genre.Footnote 207 Judson Herrman (Chapter 7) establishes that this was among the weaker arguments in The Invention of Athens. Loraux’s first reason for this exclusion was that Hyperides skipped the catalogue of exploits in order to focus on an ongoing war.Footnote 208 Herrman reminds us that, in doing this, Hyperides was in good company: Pericles and Demosthenes likewise skipped or minimised this catalogue because they realised that rehearsing it risked reawakening trenchant criticism. Happily for Hyperides, when he delivered his epitaphios logos in 323/2, he could focus on the initial stunning victories of the Lamian War.Footnote 209 Yet, Herrman shows how his speech was no less timely than those of 431/0 and 338/7.Footnote 210 In the political debates of the 320s, Hyperides had been the leading proponent of a risky uprising against the Macedonians.Footnote 211 Therefore, the focus of Hyperides 6 on immediate military success was not simply a patriotic rallying of the dēmos for a war effort. It also served as justification for Hyperides’ contentious proposal to fight in the first place.

Herrman demonstrates that Hyperides remained faithful to several other features of the genre. A good example is the sun simile that he used in place of the catalogue: it evoked standard topics of the funeral oration and gave the Athenians standard characteristics (Hyper. 6.4–5; cf. 6–8). Hyperides also made out that, in the Lamian War, the Athenians were fighting an invading barbarian people for the sake of the freedom of the Greeks (e.g. 10, 12, 16, 19–22, 37). Of course, this is the same cluster of terms that other funeral orators used to describe the Persian Wars.Footnote 212 In the same vein, Hyperides emphasised how the recent battles against the Macedonians had occurred on actual battle sites of the Second Persian War (12, 18). Hyperides’ treatment of the fallen’s ‘beautiful death’ was no less conventional: he repeatedly praised their aretē, which he defined in the same terms as the other funeral orators, and, like them, spoke of their ‘deathless glory’.Footnote 213 In reproducing such features, Herrman concludes, Hyperides was writing well within the genre of epitaphioi logoi.

Nevertheless, Herrman’s chapter readily acknowledges that this funeral speech contained two major innovations. Hyperides attributed a great deal of the recent success to the leadership of Leosthenes (e.g. 10–14, 35–40). In singling out this general for praise, he broke with the genre’s standard attribution of victory to the war dead or the Athenians as an anonymous group. The second innovation concerned the relationship that the fallen of 323/2 had with their ancestors. In other funeral speeches, those being buried were simply the latest example of an unchanging Athenian aretē.Footnote 214 Hyperides 6, by contrast, proposed a rupture: these dead were more virtuous and more successful than their ancestors (e.g. 1–3, 19, 35, 38–9). For Loraux, these innovations were further reason for seeing Hyperides 6 as ‘the least conformist’ of the extant speeches.Footnote 215 Interestingly, though, this second apparent innovation was not unprecedented. Immediately after the Persian Wars, the dēmos compared their recent victories with what their mythical ancestors had achieved at Troy.Footnote 216 Yet, by mid-century, funeral orators were arguing that the extraordinary military achievements of contemporary Athenians were far superior to those of the Trojan War.Footnote 217 An unlikely victory against the Macedonians could well have convinced the dēmos to see the Lamian War as a comparable rupture. Sadly, of course, this was not to be: within months of this epitaphios logos, the Macedonians had crushed the uprising.Footnote 218 They moved swiftly to overthrow Athenian democracy and to hunt Hyperides down.Footnote 219

1.6 Accounting for the Literary Examples

Loraux was convinced that the focus of previous scholarship on the ‘great names’ behind the extant epitaphioi logoi had prevented their study as a coherent genre.Footnote 220 Therefore, The Invention of Athens deliberately downgraded authorship as a topic of study.Footnote 221 Certainly, this made it easier for Loraux to demonstrate how the seven examples belonged to a long-stable tradition. Yet, by rejecting such a focus, she left unanswered important questions about each speech. This rejection also prevented her from accounting for a fundamental difference between the surviving epitaphioi logoi.Footnote 222 Those of Pericles, Demosthenes and Hyperides had been delivered at actual public funerals for the war dead. But the four others had been published only ever as literary works.Footnote 223 Their authors had clearly never spoken in the Ceramicus: Gorgias and Lysias, as foreigners, were not legally entitled to do so,Footnote 224 while Isocrates and Plato, famously, avoided political leadership at home. Therefore, why exactly each of them ended up writing an epitaphios logos cries out for an explanation. It is no less important to consider what light their literary works, as a group, shed on the public standing of the official speech.

Plato’s Socrates was sure that the usually foreign sophists who worked in Athens often possessed their own models of a funeral speech (Pl. Menex. 235e–6c). For him, they could also teach their rich students how to deliver one. Lysias’ epitaphios logos is, perhaps, the only one that comes close to such a model. While no teacher of public speaking, Lysias most probably wrote his example as an advertisement for his local speech-writing business. Gorgias, Isocrates and Plato, by contrast, actually were higher-education teachers, but they each made abundantly clear that theirs were not simple how-to-write examples of a funeral speech. For his part, Gorgias integrated a veritable critique of Athenian militarism into his epitaphios logos, while Isocrates transformed his into a plausible Panhellenic speech. Because of its sustained gentle parody, Castoriadis memorably described Plato’s Menexenus as ‘a cabaret version’ of the funeral oration.Footnote 225 We will see that each of these authors had his own combination of business-related and educational reasons for publishing an epitaphios logos. On the other hand, it is telling that all three felt it necessary to publicise their mastery of the genre. Although they belonged to the top rung of Greece’s higher-education market, they were not prepared to leave the funeral oration to rival private teachers. This, in itself, suggests that their main customers, namely rich Athenian fathers, thought that their sons, potential future leaders, needed to learn about the epitaphios logos. Consequently, this group of four literary examples furnishes further proof of the perceived importance of the official speech for classical Athenians.

Less than ten per cent of Gorgias’ epitaphios logos survives. In spite of this, Johannes Wienand (Chapter 8) is able to demonstrate how important it was for the emergence of the funeral oration as a literary genre. Gorgias privileged the Persian Wars as funeral orators always did (fr. D30a Laks and Most), while his characterisation of the war dead as the defenders of justice was no less conventional (fr. D28). Therefore, it is unsurprising that postclassical authors erroneously believed that Gorgias had delivered his work at a public funeral for the war dead (e.g. Philostr. V S 1.9). In his Lives of the Sophists, Philostratus also noted how this speech argued unconventionally for the genre that the Greeks should fight the Persians instead of each other. Nevertheless, as far as this Roman-period author was concerned, Gorgias carefully downplayed what effectively was direct criticism of the dēmos’ warmaking. For Philostratus, criticism went no further than the claim (fr. D29): ‘Trophies over the barbarians call for hymns of praise, those over Greeks call for lamentations.’Footnote 226

Wienand demonstrates that Philostratus seriously underestimated the extent of Gorgias’ critique. His funeral speech also mentioned vultures feeding on unburied war dead.Footnote 227 As the classical Greeks saw burying the fallen as a divinely sanctioned custom, which stasis (‘civil war’) often prevented,Footnote 228 here, too, Gorgias seems to be criticising inter-Greek wars. This criticism, Wienand argues, carried over to the characterisation of the Athenian dead themselves. The epitaphic convention was to praise them primarily or, at times, exclusively for their decision to die in battle.Footnote 229 Gorgias, by contrast, also lauded them at length for their significant contributions to civilian life (fr. D28). For Wienand, this is another clear statement about the human costs of Athenian wars against fellow Greeks.

His chapter makes a detailed case for the date of this text. As the epitaphios logos appears to have been a uniquely Athenian genre, all agree that it must have been composed after 427,Footnote 230 when Gorgias first arrived and made Athens a regular place of residence.Footnote 231 But there is no consensus when exactly, in the next fifty years, he wrote his version of the genre.Footnote 232 Wienand gives two reasons for him doing so in the late 420s. The first is the battle of Delium of 424/3, after which the Thebans refused to let the Athenians promptly bury their fallen soldiers (Thuc. 4.97–101). Gorgias’ vulture metaphor seems to evoke this controversy. The second reason is Gorgias’ use of the speech to display his mannered rhetoric. As the Athenians, it seems, quite quickly grew tired of it,Footnote 233 this too points to an early date. Wienand’s dating suggests that it was Gorgias who invented the writing of a funeral oration as a text primarily for publication. In writing their own literary epitaphioi logoi, Isocrates and Plato followed him in interweaving criticism of the dēmos. Wienand’s dating gains further support from the fact that within a month of arriving, Gorgias, as a foreigner, was required to register as a metoikos (‘metic’).Footnote 234 As the classical Athenians expected metics to support the status quo,Footnote 235 the sheer brazenness of the criticism of them in his epitaphios logos suggests that Gorgias had not been in Athens for very long.

Wienand’s chapter, finally, sheds light on discourses about war in classical Athens. Gorgias regularly gave display speeches,Footnote 236 which, it seems, helped him to attract elite students for his higher-education classes in public speaking (Pl. Meno 95c). He also used texts that he had written as learning tools in such classes.Footnote 237 His decision to demonstrate his mastery of the epitaphios logos suggests that elite Athenian fathers judged it important for their sons to learn such a speech. This means that it attests to the oral genre’s importance and prestige under Athenian democracy. Wienand notes what this speech also tells us about private discourses on war. On the Peace, which Isocrates wrote in the 350s, is often seen as the earliest sustained critique of the dēmos’ militarism among elite Athenians.Footnote 238 Wienand’s conclusion is that Gorgias’ speech pushes such elite critique right back to the 420s.

Loraux judged Lysias 2 to be ‘a perfect example’ of a funeral speech.Footnote 239 Her judgement, which continues to be influential, was entirely sound.Footnote 240 Lysias’ epitaphios logos rehearses more generic topoi than any other example, is organised like the others and covers all the standard topics.Footnote 241 Consequently, Loraux quite rightly drew heavily on Lysias 2 in her analysis of the genre.Footnote 242 In spite of this, The Invention of Athens said very little about Lysias as an author.Footnote 243 Again, this was due to Loraux’s efforts to prove that the extant funeral speeches emerged out of a long-stable genre. The result was that her first book left unanswered two fundamental questions about Lysias 2. The first is whether Lysias actually wrote it. For a long time, the modern consensus was that he did not.Footnote 244 If he did write it, the second question is why. Lysias’ decision to author an epitaphios logos would require an explanation because he, as a metoikos, could never have spoken at a public funeral for the war dead.

In answering these questions, Alastair Blanshard (Chapter 9) helps to re-integrate authorship into the study of the epitaphic genre. In the 1860s, Friedrich Blass argued that Lysias 2 was a school writing exercise.Footnote 245 Blanshard’s chapter shows how weak this argument always was. In the 380s, Isocrates, in his Panegyricus, copied passages from Lysias 2, while Plato, in the contemporaneous Menexenus, parodied other passages.Footnote 246 If Lysias 2 were a forgery, it would have been published at the height of Lysias’ career as a speech writer, which is highly unlikely. Blanshard points out that postclassical writers also debated which of the speeches that were attributed to Lysias were genuine. Significantly, they all agreed that Lysias 2 was one of the genuine ones. Clearly, we have good reason to believe that Lysias actually authored this epitaphios logos.

Blanshard locates the explanation of why Lysias wrote it in both his metic and economic status. Lysias lost his considerable personal fortune during the short oligarchy that followed after Athens’ defeat in 404.Footnote 247 The oligarchs stole most of his assets and Lysias spent what he had left on helping the dēmos to regain power in 403. Afterwards, Lysias was forced to earn his living as a logographos (‘speech writer’). To drum up business, he is known to have delivered display speeches to private audiences (e.g. Pl. Phdr. 227c–8d). We know too that he published at least one speech that he never publicly delivered. Lysias 12 was ostensibly his speech, at an extraordinary euthuna (‘public audit’), against the Athenian oligarch who had done his family the most harm. Because a metic could not speak in such a court case, Lysias 12 was only ever a published work.Footnote 248

As the funeral oration was such a prestigious genre, Lysias, according to Blanshard, also saw a business advantage in publishing one.Footnote 249 Blanshard links this speech’s entirely conventional content to Lysias’ personal circumstances. Whereas Plato, as a citizen, could parody the genre, this was not an easy option for Lysias. As a metic, he was expected not to rock the boat, while, as a logographos, he got work because he was good at writing what non-elite jurors wanted to hear.Footnote 250 Therefore, it is not surprising that Lysias 2 carefully reproduces as many of the genre’s topoi as possible as well as its flattering characterisation of the dēmos. For Blanshard, Lysias’ status also accounts for the speech’s sole unconventional feature: the praise of the xenoi (‘foreigners’) who died fighting the oligarchs (Lys. 2.66). Here Lysias was again poignantly reminding the Athenians of the high price that metics, like him, had paid in helping to restore their democracy.

Ancient historians have always struggled to account for Plato’s Menexenus, in which Plato, whose dialogues typically included harsh criticisms of Athenian democracy, paradoxically had Socrates deliver a conventional epitaphios logos.Footnote 251 His speech rehearsed most of the standard topoi as well as the same flattering characterisation of the Athenians: they were unsurpassed in aretē and always just in foreign affairs.Footnote 252 Therefore, in spite of Plato’s persistent criticism of Athenian democratic politics, the Menexenus provides surprisingly strong evidence for the epitaphic tradition in the early fourth century. Ryan Balot (Chapter 10) finds an explanation of this paradox in the primary use to which Plato put his dialogues. In his school, such texts served as starting points for discussions on ethics. Balot argues that Plato matched his dialogues to the general levels of his students. This means that accounting for the Menexenus requires us to work out how advanced its intended readers were in their philosophical studies. For Balot, this should have been the same as the attainment-level of the dialogue’s eponymous character. Menexenus, clearly, is at the beginning of his higher education: he uncritically believes in what funeral orators claim and relies entirely on Socrates’ guidance.Footnote 253 This suggests that Plato wrote the Menexenus for students who were new to the study of philosophy.

Certainly, such a readership accounts for this dialogue’s decidedly gentle treatment of the funeral oration. In other dialogues, such as Gorgias and Protagoras, Plato harshly attacked some of this genre’s core claims because his readers were much more advanced in their study of philosophy. For beginners, however, who were still immersed in civic ideology, such an attack could have easily offended and alienated them. Balot shows how Plato, in his Menexenus, aimed for less: he wanted his students to begin to see the problems in how this prestigious genre praised the Athenians. Plato’s main method for achieving this aim was straightforward: he exaggerated the discursive practices that the funeral orators habitually used for the sake of perpetuating the stereotypical characterisation of the Athenians.Footnote 254 Plato has Socrates conclude his epitaphios logos by recounting the advice about aretē that the war dead supposedly left their sons. Balot shows how the pronounced incoherence of this advice cast serious doubt on the epitaphic topos that democracy was a good teacher of aretē.Footnote 255 Therefore, Plato’s new students were left with the clear impression that their group discussions with him about ethics really were indispensable.Footnote 256 In short, he could teach them what Athenian democracy could not.

Isocrates was another higher-education teacher who publicised his mastery of the epitaphic genre. For her part, Loraux thought that ‘the first half’ of his Panegyricus could be ‘easily reduced to a sort of epitaphios’.Footnote 257 Isocrates knew well the business-related reasons for publishing such literary speeches.Footnote 258 He had started his working life as a logographos. In the 380s, when he wrote the Panegyricus,Footnote 259 he was setting up his own school for philosophy, which specialised in public speaking.Footnote 260 In this new business, two of his rivals, Gorgias and Plato, had already published literary epitaphioi logoi. His old rival as a logographos, Lysias, had done the same. Therefore, Isocrates could see the value of publicising what he could do in this prestigious and important genre.Footnote 261 He also followed Gorgias and Plato in giving his version of the funeral oration an unexpected twist: he embedded it in an epideictic speech supposedly for a Panhellenic festival. The result was that the Panegyricus acquired a respectable Panhellenic argument: the Greeks should stop fighting each other in order to wage a new Persian War (e.g. 4.3, 6, 15, 19, 66, 166, 173, 187). Nevertheless, there was still an enormous amount of epitaphic content in his first major literary work.Footnote 262 For example, Isocrates appeared to characterise the Athenians in the same terms as the funeral orators did: they had always fought just wars (e.g. 4.52–4, 71, 75, 85, 91, 95). As proof, he introduced the genre’s standard myths as well as its standard battles from the Persian Wars (51–98). His Panegyricus even cannibalised specific passages from the funeral speeches of Pericles, Gorgias, Lysias and Plato.Footnote 263 For Loraux, this reworking was no more than ‘obvious plagiarism’.Footnote 264

Thomas Blank (Chapter 11) makes clear that Isocrates’ relationship to the funeral oration was more complex. In his Panegyricus, Isocrates was adapting, as he acknowledged (4.74, 98), the genre for the sake of his Panhellenic argument. As he was arguing for a new Persian War under the joint leadership of Athens and Sparta, Isocrates, in contrast to funeral orators, restricted his historical erga to the Persian Wars, expanding Sparta’s role in them.Footnote 265 In reworking Pericles, moreover, he transformed boasts about Athens into proofs of its longstanding Panhellenism.Footnote 266 Blank’s chapter also suggests that Isocrates’ speech served a further educational purpose. In the classroom, Isocrates, it is clear, used his literary speeches as examples of arguments.Footnote 267 He wanted to teach his students how to match them to a target audience, which was a must-have skill for future political leaders of Athenian democracy.Footnote 268 The Panegyricus, according to Blank, purposefully mismatched the two by rehearsing parochial Athenian content for a supposed audience of non-Athenians. Consequently, it could serve as a useful example of how not to make an effective argument.

Blank reminds us that Isocrates’ relationship to the genre drastically changed a quarter of a century later. On the Peace, which he wrote after the costly defeat of Athens in the Social War of 357–5,Footnote 269 was an unparalleled condemnation of Athenian militarism.Footnote 270 It shows us the direct criticism of this state’s wars that was simply missing in Athenian public discourse.Footnote 271 Funeral speeches typically argued that the Athenians always fought justly, that their arkhē (‘empire’) had been unambiguously good and that their wars had always brought benefits. In contrast, On the Peace contends that the Athenian dēmos stopped fighting justly after the Persian Wars (e.g. 25–7, 30, 37–8, 42, 47, 90–1), had been corrupted by their arkhē (e.g. 64, 77, 88), and often died in appalling numbers in crushing defeats (e.g. 84–7). This appears to be a deliberate refutation of what speakers said in the Ceramicus.

That On the Peace really was an anti-funeral oration is suggested by how it treated the public funeral for the war dead and the parade of their male orphans at the Great Dionysia. The dēmos saw both ceremonies as significant timai for the fallen, which encouraged the living to be courageous.Footnote 272 On the Peace makes them perversities advertising the appalling human cost of Athenian wars (82, 87–8). The Social War had been a huge financial burden on rich Athenians.Footnote 273 As they paid his school fees, it might be argued that Isocrates’ only motivation for now writing against the funeral oration was to curry their favour. Against this, Blank shows that Isocrates 4 and 8 were less inconsistent than appearances might suggest. Although it is subtle, the Panegyricus actually also characterised Athenian Wars after 479/8 as unjust (Isoc. 4.6, 100–2, 110, 158, 166, 172). This means that Isocrates criticised Athenian militarism in published works for several decades.Footnote 274 That he got away with it implies that such criticism was a common conversation topic among elite Athenians throughout the fourth century.Footnote 275

1.7 Completing the Intertextual Analysis of the Genre

Perhaps the biggest gap in The Invention of Athens was intertextuality. Loraux correctly recognised that there were ‘traces’ of the funeral oration across Athenian literature.Footnote 276 But she never systematically compared the epitaphic genre with other public oratory and drama.Footnote 277 Therefore, The Invention of Athens could not put beyond doubt whether the other forums of Athenian public discourse reinforced, questioned or ignored the funeral oration’s standard content. A major goal of our edited volume is to fill this significant gap in Loraux’s first book.

Of course, the Athenians of the epitaphios logos went to war for just reasons, such as the protection of persecuted weak states, and were almost always victorious. The traditional belief is that this rosy-coloured characterisation of Athenian polemos had no place in deliberative oratory.Footnote 278 For a long time, ancient historians believed that foreign-policy debates in the Athenian assembly were based solely on the calculation of ‘national’ interest (Figure 1.4).Footnote 279 For them, the funeral oration was simply an illusion that obscured the Realpolitik of Athenian foreign affairs.Footnote 280 From the Marxism of the 1970s, however, Loraux learnt that the self-identity of a people mediates their relationship to reality and has a significant impact on their public life.Footnote 281 Indeed, Loraux repeatedly hypothesised that this rosy-coloured account of Athenian wars could well have affected enormously foreign affairs.Footnote 282 But she never undertook the systematic comparison of the funeral oration with deliberative oratory that was required to put her hypothesis beyond doubt. Peter Hunt (Chapter 12) completes this critical intertextual analysis of the two genres.

Figure 1.4 The meeting place of the Athenian assembly on the hill of the Pnyx.

Initially, Hunt’s chapter casts serious doubt on Loraux’s hypothesis. Athenian politicians, when debating war or peace, always introduced security-related reasons.Footnote 283 Typically, they emphasised such reasons by beginning or concluding their assembly-speeches with them.Footnote 284 Their reasons ranged from calculations about Greece’s balance of power or the state’s armed forces to, for example, the cost of a war to the public purse.Footnote 285 The school of Realism in International Relations assumes that a state calculates foreign policy only on the basis of such reasons.Footnote 286 Therefore, it is understandable that Realists see classical Greece as a historical example supporting their school.Footnote 287 Nevertheless, Hunt shows that Athenian politicians, in their foreign-policy debates, also regularly called into question the funeral oration’s characterisation of the Athenians.Footnote 288 Andocides, for example, reminded them of the heavy costs that they had paid for protecting persecuted weak states (e.g. 3.9, 28–31), while Aeschines said the same while also arguing that the victories that their funeral speeches celebrated were no proof of future success.Footnote 289 Hunt rightly points out that the need that Athenian politicians felt to argue against the funeral oration reveals the genre’s real impact on debates about war and peace.