Introduction

Historically, India is known for the co-residential arrangements of multigenerational families. Within these arrangements, family members share economic resources and the responsibilities for household tasks. The distribution of different tasks between family members often follows a similar pattern, in which the older generation supports the raising of the grandchildren, and the children and grandchildren take care of their (grand)parents when they become more care dependent. Furthermore, the elderly generation supports the younger generation with their wisdom and life experience. Historically, female family members take more responsibility for household tasks, while male family members are responsible for generating family income by working outside the house. These intergenerational practices in joint families are assumed to establish a strong bond between older adults and their adult children as well as their grandchildren (Chadha, Reference Chadha2004), and thereby facilitate emotional support in addition to the aforementioned practical and economic support (Chadha, Reference Chadha2004; Ugargol et al., Reference Ugargol, Hutter, James and Bailey2016), thereby creating security (Asis, Reference Asis, Iredale, Hawksley and Castles2003; Willson et al., Reference Willson, Shuey and Elder2003) and improving quality of life (Krause, Reference Krause, Binstock and George2001). This traditional co-habitation arrangement could persevere for a long time because such an arrangement facilitates older adults in maintaining and passing along traditional values and customs, such as family cohesion, reciprocity, sharing and filial piety, to the younger generations (Chadha, Reference Chadha2004; Pillai et al., Reference Pillai, Levy and Gupta2012; Kadoya and Khan, Reference Kadoya and Khan2015), thus promoting the continuation of reciprocity in relationships in which younger generations who received throughout their life repay the eldest generation by meeting their needs when they grow old (Lamb, Reference Lamb2013; Watt et al., Reference Watt, Perera, Østbye, Ranabahu, Rajapakse and Maselko2014).

In recent decades, however, drastic changes to the traditional co-habitation arrangement of Indian families have occurred. As in other Asian countries, better education and labour market transitions because of the processes of globalisation have resulted in job opportunities for younger generations beyond traditional close-to-home options. This process has created the increased mobility of the younger generations, who are moving into cities or abroad in pursuit of these opportunities for better jobs (Arockiasamy et al., Reference Arockiasamy, Bloom, Lee, Feeney and Ozolins2010; Bloom et al., Reference Bloom, Mahal, Rosenberg and Sevilla2010; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018). As parents stay behind, this change has resulted in more nuclearised family arrangements (Rajan and Kumar, Reference Rajan and Kumar2003; Chadha, Reference Chadha2004; Krishnaswamy et al., Reference Krishnaswamy, Sein, Munodawafa, Varghese, Venkataraman and Anand2008; United Nations Population Fund, 2012).

Many scholars who have investigated this development have emphasised what is lost for the elder generation with this nuclearisation of Indian families (Chadha, Reference Chadha2004; Krishnaswamy et al., Reference Krishnaswamy, Sein, Munodawafa, Varghese, Venkataraman and Anand2008; Brijnath, Reference Brijnath2012; Dommaraju, Reference Dommaraju, Guilmoto and Jones2016). Because the intergenerational exchange of traditional values is seen as inextricably bounded up with or embedded in co-residential arrangements as such, the breakdown of these arrangements would automatically lead to the breakdown of the value exchange as well. Indeed, some research supports this assumption and shows that these transitions (Willson et al., Reference Willson, Shuey and Elder2003) have led to loosened family ties and family values (Krishnaswamy et al., Reference Krishnaswamy, Sein, Munodawafa, Varghese, Venkataraman and Anand2008; Brijnath, Reference Brijnath2012; Dommaraju, Reference Dommaraju, Guilmoto and Jones2016) and hence to the neglect, isolation and marginalisation of older relatives (Bongaarts and Zimmer, Reference Bongaarts and Zimmer2002; Chadha, Reference Chadha2004; Desai et al., Reference Desai, Prakash and Singh2010; Nagaraj et al., Reference Nagaraj, Mathew, Nanjegowda, Majgi and Purushothama2011; Sathyanarayana et al., Reference Sathyanarayana, Kumar and James2012; Samanta et al., Reference Samanta, Chen and Vanneman2014; Lloyd-Sherlock et al., Reference Lloyd-Sherlock, Penhale and Ayiga2018). These transitions are perceived to have caused loss of basic support and diminished subjective wellbeing among rural older adults (Connelly and Maurer-Fazio, Reference Connelly and Maurer-Fazio2016).

Amidst these challenges, studies (United Nations Population Fund, 2012; Burholt and Dobbs, Reference Burholt and Dobbs2014; Dhillon et al., Reference Dhillon, Ladusingh and Agrawal2016) indicate a meagre rise in older adults’ preference to live independently of their children in the recent past. Existing literature (Laungani, Reference Laungani, Roopnarine and Gielen2005; Kalavar and Jamuna, Reference Kalavar and Jamuna2011) in India points out a more optimistic perspective about the wellbeing of elderly individuals in the changing living arrangements, while raising questions as to whether and how these changes actually impact the care and support exchanges between elderly individuals and their children. According to studies by Laungani (Reference Laungani, Roopnarine and Gielen2005), Liebig (Reference Liebig2003) and Kalavar and Jamuna (Reference Kalavar and Jamuna2011), economically independent older adults often report enjoying the freedom and personal space that independent living arrangements bring.

However, a few studies (Bailey et al., Reference Bailey, Hallad and James2018; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Baileyin press) have emphasised that families do put effort into maintaining traditional family values. Bailey et al. (Reference Bailey, Hallad and James2018), for instance, share that older adults in transnational families share how their younger relatives remain in contact through electronic media and special visits. Other studies have shown that the middle generations try to meet their care responsibilities but while doing so, they become trapped between the demands of the modern work life and meeting their elder-care responsibilities (Chandra, Reference Chandra2010; Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Pruchno, Wilson-Genderson, Murphy and Rose2011; Pei et al., Reference Pei, Luo, Lin, Keating and Fast2017). Daughters and daughters-in-law especially struggle as within families, they are often still the main care-givers for their parents or parents-in-law (Wakabayashi and Donato, Reference Wakabayashi and Donato2005; Lilly et al., Reference Lilly, Laporte and Coyte2007; Berecki-Gisolf et al., Reference Berecki-Gisolf, Lucke, Hockey and Dobson2008; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Baileyin press). Additionally, studies from other countries provide a more nuanced picture and show that traditional norms and emotional bonding in multigenerational families continue to exist despite changing living arrangements (Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2001; Marks et al., Reference Marks, Lambert, Jun and Song2008; Watt et al., Reference Watt, Perera, Østbye, Ranabahu, Rajapakse and Maselko2014; Bastawrous et al., Reference Bastawrous, Monique, Moira and Jill2015). Verbrugge and Ang (Reference Verbrugge and Ang2018) give the reciprocity patterns in maritime South-East Asian families, where adult children meet the financial and material needs of older adults for their services to the family through effort and time, as well as mutual exchange of tangible intergenerational support.

Although most studies seem to suggest that the nuclearisation of Indian families should be considered as a loss because it creates a decline in traditional family values and a deprivation of family-based informal care and support, evidence with regard to the impact of the change in living arrangements on both traditional values and care arrangements for the elderly population in India is inconclusive. Most studies related to intergenerational care have been quantitative in nature and have lacked a deeper subjective understanding of the relational dynamics exchanged across family members of different generations. Moreover, these studies have attempted to capture the impact of social transitions on intergenerational care more from the older adults’ perspective and enquiries focusing on adult child care-givers’ perspectives are missing, which calls for an in-depth qualitative enquiry (Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton, Reference Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton2004; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018). Therefore, this study aims to understand the perceptions and experiences of adult children on the complexities involved in the intergenerational reciprocity of care and support amidst changing living arrangements.

Data and methods

Study background

Intergenerational care and support exchanges have been changing over recent periods due to better educational opportunities and increased economic developments (Lamb, Reference Lamb2013; Samanta et al., Reference Samanta, Chen and Vanneman2014), particularly in South India, which comprises five states, including Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Telangana. According to the 2011 census, on average, the combined literacy rate of all five states is approximately 80 per cent, which is substantially higher than the national average of 74 per cent (Census of India, 2011). All five South Indian states rank within the top ten states with the highest Gross Domestic Product in the country (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2017). Against this background, two of the South Indian states (one a well-performing state, Tamil Nadu, and the other a poorly performing state, Telangana) were selected for large-scale qualitative research to examine the intergenerational exchanges and the wellbeing of the elderly population in South India. This paper was based on the views and experiences of adult children in the selected states.

Participants and sampling

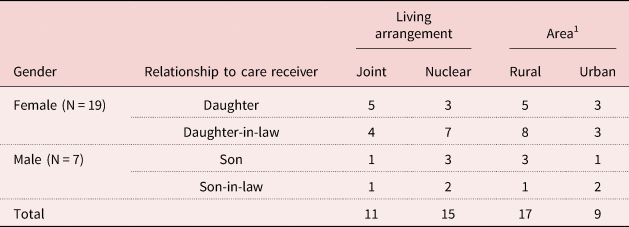

The participants were approached with the help of non-governmental organisations and senior citizens associations. Adult children from traditional living arrangements, where they co-resided with their older relatives, as well as from nuclear living arrangements, where their older kin lived apart and not in the same household, were selected using purposive sampling techniques in the selected states. The participants were selected from diverse socio-economic backgrounds until data saturation was reached. Based on these criteria, 26 adult care-givers were selected, of whom 19 were female and seven were male. The age of the participants ranged from 25 to 58 years. Eleven participants were from co-residential living arrangements and 15 were from nuclear families. The proximity between the participants living in a nuclear arrangement and their older relatives ranged from living on the next street to living in a different part of the state. The socio-demographic background of the participants is given in Table 1.

Table 1. Socio-demographic background of the participants

Note: 1. Urban area refers to statutory towns, census towns and outgrowths, and all areas other than urban are rural areas, which mainly consist of villages (Census of India, 2011).

Methods and procedures

Researchers followed an interpretative approach (Ulin et al., Reference Ulin, Robinson and Tolley2005; Tolly et al., Reference Tolly, Ulin, Mack, Robinson and Succop2016) to capture the socio-culturally rooted perceptions and experiences of adult children in their intergenerational relationships (Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton, Reference Raschick and Ingersoll-Dayton2004; Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018) with their older relatives. By referring to a broad range of international and national literature, an in-depth interview guide was constructed, and the broad focus of the questions included challenges experienced by the participants in providing informal care to their older kin and the measures they adopted to overcome those challenges. The guide was then translated into local languages, namely Tamil and Telugu. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Manipal Academy of Higher Education, India. Subsequently, selected adult child participants were approached and informed about the nature and objectives of the study, and anonymity of their responses. Upon taking informed consent, in-depth interviews were conducted with audio recording, which were then transcribed by a professional transcriber in verbatim format for data analysis.

Data analysis

The researcher ensured the accuracy by verifying the transcribed data with the audio recordings. The transcripts were then fed into NVivo 9. Following the principles of thematic analysis, the following steps were followed to analyse the data: upon thorough reviewing of the transcripts, line-by-line coding was done in the first round, which included both deductive and inductive codes. In the second round, the codes and the related texts were re-examined and a refined code list was developed (Ugargol and Bailey, Reference Ugargol and Bailey2018). Subsequently, the associated codes were clustered and patterns of participants’ experiences were identified. Based on these processes, themes and sub-themes were derived that were rooted in the participants’ responses in the interviews (Smith and Osborn, Reference Smith and Osborn2015).

Results

This section describes the experiences of adult children in traditional co-residential living arrangements and in modern nuclearised situations, starting with the challenges they encounter related to caring for their parents in the context of their daily life. In the second part of this section, the strategies they employ to overcome these challenges are discussed.

Increased demands of modern life

Our analysis shows that participants in general have experienced an increasing burden due to the increased demands and responsibilities that modern life has brought about. They feel that there has been a large change in the nature of work life, which, for example, expects them to work beyond the regular working hours to fulfil their designated roles via technology platforms in regard to meeting job requirements. Previously, when their work demands were less, they felt it was easier to balance their work and family responsibilities. Now, these increased demands are perceived to make their daily schedule busier, thus permitting less time for them to manage their household responsibilities, including elder-care. These experiences were expressed by participants in both modern and traditional living arrangements:

Before I joined here at HelpAge India [organisation] and started working, I went many times and they [parents] also came. But now, I keep my family aside and get involved in arranging health camps and eye camps, giving medicines and attending meetings; all of these happen, sir. (Female, 26 years old, rural, modern living arrangement)

The fast life these days doesn't allow brothers to sit together and talk about taking care of their parents. (Male, 40 years old, urban, traditional living arrangement)

Special preferences and requests of older kin

As the participants juggle these increased responsibilities related to work and family, special preferences and requests of older relatives in the form of wanting to be heard about their concerns and not adapting to the life changes are perceived to increase further their challenges in intergenerational relationships.

Being heard

One of the common preferences of older kin referred to by participants in both living arrangements was that they expected their younger relatives to listen to their day-to-day life experiences and endorse very simple decisions related to domestic chores. By doing so, older kin are seen to consume much of the participant's time and to not care about their work schedule:

For everything, she used to get my consent or what she undergoes she shares it with me … Sometimes, I will be in a hurry; even then, I will tell her, ‘Tell me what is it’, and she will start telling me her issues, and it will take more time. Then, I tell her, ‘Mumma, I have to work, I will go and come back’, and she will get very offended, the whole day she will be upset. (Female, 47 years old, urban, modern living arrangement)

I have come across many problems, sir … They [older relatives] won't listen to what we are saying, sir; we should only listen to them. (Female, 52 years old, rural, traditional living arrangement)

In return, because the participants go through many struggles, they try to share their personal problems with their older kin to ventilate their feelings and receive comfort from them. However, they feel sad that their older relatives are not keen to listen to their concerns and prefer only to be heard. This mismatch of expectations causes disappointment to the participants, adding more friction to their relationships. A daughter participant shared the following:

The few times I tried to share my problems with her, she was not in that mentality to listen to my problems. So, when I started my thing, she immediately brought up her own issues, which was a very minor thing. When I don't listen to her, she makes it a big problem. When we want to share something, at least she could sit and listen. We are not asking for anything, no demands from my mother other than just being a mother; she could at least listen. (Female, 47 years old, urban)

Being inflexible

The participants also felt that the burden increased when their older kin did not prefer to change themselves according to the demands of modern life. Some of them spoke about the expectation of their older kin to attend to their care preferences in a way that favoured them, without realising what the implications of doing so would have on the participants’ schedule for meeting other responsibilities in their family and at work. These attention-seeking preferences are felt to have increased participants’ burden all the more, as they had to readjust their work rhythm:

Yes, we invited her to come and stay with us. But she refused, saying that she is living only on the next street, and she feels comfortable there. In her house, she has a large hall and a large bedroom where she has her own television. So, we take her food to her room and also wash her dresses, etc. (Female, 38 years old, rural, modern living arrangement)

I tell her [aunt] to wake up early and get freshened up by 10 am so that she can have breakfast by that time. It is a good habit at her age, and she can take a rest after having breakfast. But she is stubborn, and she doesn't listen … So, I adjust to the situation sometimes. (Female, 52 years old, urban, traditional living arrangement)

Another form of preference that interferes with the participants’ regular schedule and adds more burden is the unhelpful choices of their older kin. Particularly in traditional families, by the virtue of co-residence, the participants have the advantage of helping their older relatives understand the importance of adopting the right choices. However, they shared that their older relatives prefer to follow certain unhelpful choices. For example, older adults get used to eating a certain diet over a period of time and do not attempt to control those habits, irrespective of their effects on their wellbeing. Because of these unhealthy food choices, older relatives fall sick, placing additional burdens on the participants. To attend to their sickness, the participants then have to readjust their other schedules:

And she [mother] doesn't follow the proper food habits. For example, say she shouldn't take chicken at dinner; she won't accept this, and she will eat it. And after two days, she will ask me what to do for her upset stomach. Despite us trying to regulate her food habits, she may not co-operate all times. (Male, 40 years old, urban)

Extra work and costs incurred by the special preferences of older kin

All of these preferences and choices of older kin bother some of the participants from both types of living arrangement more because they also cause additional work and costs, in addition to the increased demands of modern life. One of the participants from the modern living arrangement said:

We go and look after them [parents-in-law], sir, when they are sick. (Female, 26 years old, rural)

A participant from a traditional living arrangement expressed the following:

Having one variety of food for all would balance the economic situation of the family. She [mother] may want chicken for dinner instead of greens, but she is not going to pay for it, of course. I have to do so, and cook greens for four people and chicken for one. The extra expense of money, time and work, all that, she may not consider. (Male, 40 years old, urban)

Though participants in both types of living arrangement experience the burden of additional work and costs, the specific nature of those challenges differ based on the living arrangement. The participants in modern living arrangements stated that they face challenges in travelling to meet the care needs of their older relatives who live separately, which involves extra time, energy and costs, and makes the challenge more complex:

My father-in-law died in that flat, and it is their flat. She [mother-in-law] says that she won't come and leave that flat. We tell her to come in the morning and stay with us until evening, but she doesn't come. We bring her home during the festive seasons. She is also aged above 80. She has some health issues, such as arthritis. I go and visit her sometimes and take care of her when she falls sick. (Female, 52 years old, urban)

Moreover, before they travel to support their older relatives, the participants expressed that they have to make arrangements to meet their own household responsibilities. At the time of a crucial dilemma, to prioritise their tasks, some participants have attempted to explain the additional efforts that they are putting in to provide optimal care for their older relatives; however, these attempts do not produce the expected result of reducing the older kin's expectations and thus leave the participants feeling disappointed. A participant expressed:

I am really finding it difficult to make her [mother] understand the extra efforts I put in to meet her expectations. (Female, 47 years old, urban)

On the other hand, participants from traditional living arrangements spoke about the additional domestic work caused by certain habits of their older kin. In spite of their repeated requests, in some families, the participants stated that their older relative continues to repeat certain unhygienic mannerisms. Having to witness such redundant unhelpful habits time and again because of living in the same house has caused the participants to become annoyed with these habits. The participants feel that these unhygienic habits increase their domestic work and consume more time, thereby adding more burdens to the adult children:

We have a very small house, one hall and one room and kitchen. He [father-in-law] will have something that is not agreeable for his digestion and before going to the bathroom, he will pass out motion [faeces] on the way, and my husband has to clean it. He used to throw nose-wiped clothes on the bed that could cause infections. I used to wash them and clean the bed with Dettol. We used to tell him to be clean, but he keeps repeating the same behaviours. (Female, 38 years old, urban)

Besides, in some traditional families, participants complained, due to the inflexible nature, their older kin waste resources at times, which incurs extra costs. Particularly, the economically less-advantaged participants view those wasted resources as an additional economic burden that aggravates their care-related challenges:

For example, at home, elderly people eat only half of their lunch and keep the remainder for the night time; instead of taking it back to the kitchen, they will leave it under the bed where it may get contaminated by flies, etc. (Male, 40 years old, urban)

In addition to the challenges caused by the preferences of older relatives, some participants from traditional families stated another difficulty due to care responsibility, namely that they are not able to organise their family's participation in any social occasions or special events taking place among their relatives. Due to a lack of facilities and economic resources, they are not able to make any respite arrangements to meet the care needs of their older kin and attend those events together as a family:

When we go out of town, we have to make some arrangements every time to care for him [father-in-law]. We cannot go together to attend any functions; usually, only one of us will go. (Female, 38 years old, urban)

Moreover, one of the common views put forth by some participants from both types of living arrangement is the lack of support from their relatives, as the entire burden of dealing with the older relative's preferences and choices and the related additional work falls on them. The reason for this outcome is either that the older relative has become more comfortable being cared for by the participants or the participants' other siblings are either not willing or not in a position to provide care. The participants also added that it is primarily the women of the family who have to carry this burden of fulfilling their increased responsibilities at home and the expectations of their older kin, in addition to their work demands. A participant from a modern living arrangement said:

But now, my work has also increased; earlier, it was only at ARUWE [organisation], but now I have started going out. The demand for my time outside my organisation has also increased … See, my child is also grown up, and my demands within the house are also increasing, so that I am not able to give proper time for my family. (Female, 47 years old, urban)

Participants from traditional living arrangements said:

His [father-in-law] daughter is living in Tambaram, and she cannot look after him. (Female, 38 years old, urban)

The reason for the grandparents being expelled from the family is that the wife is burdened with cooking. In the morning, she gets the children ready for school and washes the clothes, etc., and then goes to work. She can manage if you assist her with understanding; she can even cook three different meals. (Male, 40 years old, urban)

Even though the women in the family struggle to balance the various responsibilities, instead of receiving encouragement and support, in some families, the participants complained that their older kin do not appreciate the additional efforts made by their daughter-in-law. These dynamics cause more disappointment and bitterness in the family relationship:

And when they comment about their daughter-in-law to the others and when it comes back to the ears of the daughter-in-law, the problem becomes bigger. (Male, 40 years old, urban)

Not all the participants experienced these complex challenges and burdens at the same magnitude but rather to varying degrees. However, irrespective of living arrangements, one common observation was that adult children have adapted to the demands and requirements of modern life, whereas their older kin adhere to their traditional preferences, which makes the burden more complex.

Overcoming the burden

Different participants spoke about different ways of dealing with challenges in intergenerational relationships with their older relatives. Inspired by traditional norms of care obligations and emotional bonding, they claimed that there is no one specific way to deal with the burdens caused by their older kin's inflexible expectations; rather, a combination of strategies need to be followed to overcome the burdens effectively due to their complex and dynamic nature.

Traditional care obligation

In spite of the structural and functional changes in the modern Indian family, the participants reported upholding traditional family values and reasonably maintaining a cordial relationship with their older relatives to fulfil their care obligation, irrespective of the type of living arrangement or the availability of alternative support. One of the participants from a nuclear living arrangement remarked on this observation by saying:

Because she [mother] took care of me in my childhood days and also during my delivery, she took care of me like a baby. Now, I feel she is growing old and dependent, and it is my duty to take care of her … I will do my duty; I will not see whether other children are doing the same. (Female, 47 years old, urban)

Another participant from a traditional living arrangement said, ‘It is a must for us to look after my parents-in-law’ (female, 52 years old, rural).

Participants added that it is a traditional custom followed in Indian society to take care of their older parents with passion and responsibility. Seeing their parents making an effort to meet the care needs of their grandparents amidst changes in their living arrangements inspires the participants to adopt this traditional custom in modern times as well. One of the participants expressed the following:

My parents look after their parents so well, and it's a kind of guidance for us. Both sets of my grandparents are alive, and my mother packs two days’ worth of food, which she takes to them by auto … My father also likes to take care of his mother-in-law. (Female, 43 years old, rural)

Love

In addition to traditional obligation, the emotional bonding that they establish over their lifetime also inspires the participants to continue to care for their older relatives amidst the increased demands of modern life. Though they have differences and conflicts, many participants from both traditional and modern families expressed that the love they share with their older relatives causes them to make choices and weigh priorities in favour of caring and supporting them. For example:

But if there is anything, immediately, she will call me. That means she knows that I am there for her. Even though she fights with me, she knows that I am there for her, and I have given her such a support system. I will not care about others; I will just extend my support. (Female, 47 years old, modern living arrangement)

Care and affection can be seen at every incident; here, we see a lot of possible benefits only. (Female, 33 years old, urban, traditional living arrangement)

Emotional bonding was not only found among the parents and adult children but also between daughters-in-law and parents-in-law. Some daughter-in-law participants appreciated that although they have moved away from their parents, they receive parental love from their in-laws, as a participant said, ‘either for them or for me, it is like we like each other a lot. They take care of me like parents’ (female, 26 years old, rural).

Often the traditional care obligation and love go hand-in-hand, causing a sense of responsibility towards caring for their parents when they grow older, as expressed by one of the participants:

Because I love my parents so much, I want to live with them … The only reason I came here is to look after my parents in their old age. (Female, 43 years old, rural)

Strategies developed to address the care-giving burden

Inspired by traditional obligation and love, participants from both types of living arrangement talked about three similar strategies that help them deal with the burdens of the care-giving role.

Personal acceptance

One of the strategies participants adopt to manage care-related challenges was the acceptance of their older kin as they are, with their opinions, interests and behaviours. Although the interests and opinions of older kin are more conservative and sometimes do not meet the participants’ expectations or match the requirements of modern times, the participants let things go the way older kin prefer:

Yes, we have differences of opinions from some of them. But him being the eldest, we always give up for his benefit. We will let things go. It will pass. (Female, 48 years old, rural, modern living arrangement)

She is like a child and behaves like one. So, we cannot force her to do anything, and we have to go along with her to get things done. (Male, 40 years old, urban, traditional living arrangement)

Having realised that it is difficult to bring about changes in their older relatives according to the demands of modern life, some participants feel it would be better to change themselves. As a result, those participants have lowered their expectations, changed their perceptions towards their older kin and adjusted their work rhythm to consider caring for older kin as part of their daily routine, which they find a helpful way of overcoming the challenge caused by their kin's attention-seeking tendencies:

I think that I should change myself rather than trying to change my mother. I have to understand her. I cannot expect anything because she is old. We need to understand her, and in between, we have to tell her what to expect and what not to expect. (Female, 47 years old, urban, modern living arrangement)

So, I adjust to the situation sometimes … I get used to it … She takes nearly one hour or one and a half hour for bathing. So, I help her to bathe quickly every day, because it is not good for her at that age to be in the water for so long. (Female, 52 years old, urban, traditional living arrangement)

However, the participants also clarified that although they choose to change themselves, this does not mean that they always give into the demands and expectations of their older relatives, as they also have to attend to other responsibilities. They feel it is important to reach this realisation in a care-giving role, as it helps them balance demands from work and other family roles, as well as personal demands:

As they grow old, their demands on their children also increase, and we need to understand that you can never fulfil their expectations. So, just be there and provide them with what you can and make them feel at ease. (Female, 47 years old, urban)

The extent to which one can fulfil the expectations of older relatives is important; however, some participants expressed that meeting those care-related expectations with passion is crucial. Because they feel that such passion helps them to provide care with greater involvement, which in turn helps them consider care provision for their older relatives to be a part of their family life and their older kin as members of the family. This consideration helps participants not to view care-giving as an additional responsibility and, therefore, they feel less burdened:

But it comes from the heart, and I get the strength to do it. Doing it with the innermost feeling is different from doing it for the sake of doing it. I got used to it. (Female, 52 years old, urban)

Female participants predominantly spoke about caring for older relatives with passion. However, few male participants shared their experience of carrying out crucial care tasks with greater involvement. Those male participants felt good to give back to their parents in return for the care they received from them in the earlier days of their life:

I am taking care of her medical needs. And we see that she doesn't get tense or stressed. She should walk for a few minutes and should not lie down immediately after eating food [because of a heart problem] … I feel really very happy to care for my mother. (Male, 40 years old, urban)

Focus on benefits

The second strategy followed by the participants to address the care-giving burden was to focus their attention on the benefits they received from their older relatives in different ways. Participants from both types of living arrangement perceive that the care relationship with their older relatives not only benefits them personally but also the entire family. In the interviews, the participants appreciated the presence and advice of their older kin, which help them personally to gain more wisdom in managing family affairs and maturity in handling negative emotions, and that as a result, they are better able to deal with their life challenges in general:

My mother has taught me a lot of good things – how to run a family, how to treat my husband and how to bring up our children. She taught me how to react if my husband gets angry with me. She even corrects me in front of him if I make a mistake. She discusses with me about all matters. (Female, 43 years old, rural, modern living arrangement)

I feel very secure around him [father-in-law]. (Female, 43 years old, urban, traditional living arrangement)

In addition to personal benefits, some participants focused on the economic gains they enjoy through the care provision in both types of family situation. Although some participants complained about the increase in cost due to the personal preferences of older relatives, some participants receive economic support from their older kin to varying degrees, from meeting petty expenses, such as the purchase of cookies for their children, to larger investments, such as purchase of a property. Though such economic exchanges did not take place in all families, the participants from the families in which such transfers took place feel that those economic contributions outweigh the economic burden caused by the special preferences of their older kin.

For example, a participant from a modern living arrangement responded:

I came to know about this place being sold, and my mother bought this place and built a house for me in the same compound. (Female, 43 years old, rural)

Another participant from a traditional living arrangement said:

Recently, there was a marriage on my father's side, and she [mother] said that since she is getting pension, she will take care of that [major expense]. And if we all have to go, we share Rs. 500/person of the expenses. (Male, 40 years old, urban)

Another benefit for the entire family realised by the participants was the instrumental support extended by their older kin. The participants value the contribution of their older relatives in areas such as child care, performing household chores, cooking and offering refreshments, as they perceive those types of support as larger gains compared to the temporary regrets caused by differences in the intergenerational relationship. The instrumental support offered by the older relatives is felt to reduce the participants’ household responsibilities and offer space for them to balance work life, household responsibilities and addressing the care demands of older relatives. In modern families, the participants appreciate the extra visits made by the older kin, whenever needed, to be supportive of the participants’ family:

Our house was very small, so we got them a separate house. They used to take care of my husband and children when I went to work or when we went out of the city to attend some function, etc. He used to buy provisions, and they cooked for my husband in my absence. It's always better to have some of our relatives here at home when we are not here. They used to come and stay here and take care of my husband. (Female, 53 years old, rural, modern living arrangement)

I can carry out my work at home, and I can go out peacefully knowing that he [father-in-law] will look after the house. And we can go out of town for a couple of days, while he takes care of the house. (Male, 45 years old, rural, traditional living arrangement)

Through these intergenerational engagements, the participants perceive an additional benefit that their children receive. They appreciate the contribution of their older kin in providing a comfortable care environment and offering grandparental love, which their children also seem to value in those situations. In addition to love and care, participants from traditional families also believe that their children benefit by learning social values when observing their parents, who generally live according to those values:

My husband and I do not have many relatives from my husband's side. So, my father, my mother and my brother are all I have got. For example, I am here, and if my children come home, she [mother] will take care of them. (Female, 43 years old, rural, modern living arrangement)

It's a big support for our children. They have a good interaction, and the children are happy when the grandmother is here, and the grandmother is happy to have the grandchildren around her. They like to hold their grandmothers’ hands and go to the shops more than with us. I have seen that when my mother-in-law visits, my children hold her hand and go out to the shops. Children are longing for that kind of moment. We have to see that they get more of it. (Male, 40 years old, urban)

This emphasis or focus on the benefits they also experience from the intergenerational relationship help them to put the challenges into perspective and to put up with them, which make it more doable for adult children.

Distribution of care tasks

Thirdly, the support received from other family members and relatives in different forms seem to help the participants to deal with care-related challenges. Some of them complained that the entire care responsibility falls on their shoulders, whereas others who receive support from their siblings and relatives feel fortunate to have them share in the care-giving responsibilities, which also includes male relatives. According to the participants, different forms of support are offered, ranging from listening to the emotional distress caused by care provision to being physically present to provide respite for the participants from the care-giving role, and this support is felt to reduce their burden:

One of my sisters takes her shopping twice or thrice a month. She satisfies my mother by buying her what she likes. My mother complains of pain but suddenly, when my sister calls her to go shopping, she will immediately go. (Female, 47 years old, urban, modern living arrangement)

Both [participant and her husband] of us take care of her [aunt] as our mother. (Female, 52 years old, urban, traditional living arrangement)

Discussion

The aim of this research was to explore the experiences and perspectives of adult children with regard to intergenerational relationships. In line with other studies (Grandey and Cropanzano, Reference Grandey and Cropanzano1999; Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2001; Bakker and Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2007; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Shyu, Chen and Yang2011; Watt et al., Reference Watt, Perera, Østbye, Ranabahu, Rajapakse and Maselko2014), i.e. holding full-time jobs compromises care responsibilities and interferes with upholding traditional family values, the interviews with the adult children in our study paint a picture in which adult children, irrespective of whether they live with their older kin under one roof or live apart, struggle to combine the requirements of modern life with the care for their parents. Consistent with studies by Conde-Sala et al. (Reference Conde-Sala, Garre-Olmo, Turro-Garriga, Vilalta-Franch and López-Pousa2010), Lou et al. (Reference Lou, Kwan, Leung and Chi2011) and Pinquart and Sorensen (Reference Pinquart and Sorensen2003), that dealing with the behavioural difficulties of older relatives increases their workload and causes financial strain (Watt et al., Reference Watt, Perera, Østbye, Ranabahu, Rajapakse and Maselko2014), particularly in low-income families, the picture adult children paint in our study also shows parents who remain traditional in their expectations are less flexible in adapting to modern life. This adherence to traditional values and expectations is then linked to a lack of understanding for the children's own challenges and problems, and unwillingness on the part of their elderly kin to adjust to the schedules and possibilities of their adult children. Having to deal with these expectations further complicates balancing between their parents’ needs and other work and family duties, and increases the burden, particularly for women in the family who generally play an active care-giving role, the picture shows. Contrary to some of the Indian literature, however, that has emphasised that familial values and kinship are breaking down (Rajan and Kumar, Reference Rajan and Kumar2003; Krishnaswamy et al., Reference Krishnaswamy, Sein, Munodawafa, Varghese, Venkataraman and Anand2008), the interviews in our study depict adult children who are not indifferent to their parents needs, nor unwilling to provide care and support to their older relatives. On the contrary, the image arising from our study affirms that adult children value traditional cultural values, including cohesion, love and filial piety, even though the family structure is undergoing changes.

Although our study reflects geographical separation of adult children from their older relatives due to urbanisation and globalisation, the adult children in this study do paint a picture in which they put effort into maintaining the family contact and support, implying that family ties will not necessarily break if the extended family is not living together, as claimed in some studies (Rajan and Kumar, Reference Rajan and Kumar2003; Chadha, Reference Chadha2004; Krishnaswamy et al., Reference Krishnaswamy, Sein, Munodawafa, Varghese, Venkataraman and Anand2008) or when workload and duties of extended family life became overwhelming. Rather, the picture derived from the interviews shows how attempting to live up to traditional values, adult children in both types of living arrangement make use of a number of strategies that help to keep all balls up in the air.

A first strategy is the redistribution of care responsibilities among siblings and relatives. Traditionally, the care responsibility of older parents rests with the oldest son (Chadha, Reference Chadha2004). However, currently, our data reveal how adult children and their spouses talk about redistributing care responsibilities among their siblings and relatives that helps them to balance the various demands related to modern life better with their role as providers of care and support. Consistent with the findings of studies such as those from Ingersoll-Dayton et al. (Reference Ingersoll-Dayton, Neal and Hammer2001), Rozario et al. (Reference Rozario, Chadiha, Proctor and Morrow-Howell2008) and Watt et al. (Reference Watt, Perera, Østbye, Ranabahu, Rajapakse and Maselko2014), the image obtained from the interviews reaffirms that sharing care-giving tasks among siblings, other family members or relatives helps adult children minimise burnout. Although, the amount and nature of care task sharing varies from family to family, depending on the number of siblings or family members, the distance and the older adults’ acceptance, the strategy of sharing not only seems to offer respite, but also makes it possible to continue providing care with passion. Moreover, the adult children also described the involvement of male adult children in intergenerational care, which has traditionally been seen as the women's responsibility in Indian families. In line with the observations of a few overseas studies (Pinquart and Sorensen, Reference Pinquart and Sorensen2006; Lilly et al., Reference Lilly, Laporte and Coyte2007), the interviewees in our study highlighted that in both living arrangements men have started to either take a lead role or support their spouse in meeting the care needs of their older relatives.

A second strategy to deal with the combined challenges of modern work life with traditional care responsibilities also highlighted in the interviews is to focus on the benefits received from their older kin rather than on the difficulties involved in maintaining the intergenerational care relationships. Consistent with the reciprocity patterns highlighted by Verbrugge and Ang (Reference Verbrugge and Ang2018), the picture arising from the interviews shows how tangible and intangible support is exchanged between parents and their adult children in multigenerational families in both living arrangements. Focusing on the support received from their parents indeed helps to put the burden in perspective, according to our interviewees, while it gives them some relief. These findings are also in line with existing literature that asserts that emotional (Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2001; Ingersoll-Dayton et al., Reference Ingersoll-Dayton, Neal and Hammer2001), economic (Heid et al., Reference Heid, Zarit and Fingerman2016) and instrumental (Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2001; Ingersoll-Dayton et al., Reference Ingersoll-Dayton, Neal and Hammer2001) support from older relatives helps to build a quality relationship between adult children and their older relatives, and thereby reduces the experienced burden.

A third strategy rising from our interviews concerns acceptance of the situation. In their interviews, adult children in both types of living arrangements explain how they try to develop a sense of acceptance, how they try to change their views towards their older relatives, and how they try to consider the care-giving role as a part of their regular routine. This, they say, makes the process much easier.

The picture arising from our data shows adult children who do not intend to compromise the quality of care but who rather constantly make an effort to meet the care needs of their older kin and who try to adhere to the traditional values underlying intergenerational care. However, they do admit that at times, they fail to meet the care expectations of their older kin due to other priorities of modern life.

To conclude, changes in work life and complexities in intergenerational relationships do increase the challenges of the adult children, but they strive to overcome those challenges. In spite of modern life requirements and changing living arrangements, they seem to uphold the cultural values and norms related to providing intergenerational care and support, even when older adults are traditional in their expectations and actions. Given the dearth of studies exploring adult children's experiences related to intergenerational relationships in modern times in India, the present study makes an important contribution to the existing literature as it shows that in spite of increased challenges, and inspired by emotional bonding and moral obligation, adult children have several strategies at their disposal that enable them to combine the requirements of modern life with the traditional norms and values that oblige them to provide intergenerational care and support. This finding calls for future research to focus on the positive intergenerational family dynamics that promote bridging the gaps in family-based informal care for older adults. Not all families are equipped to deliver complete intergenerational care for their older relatives; therefore, services and programmes need to be developed to support adult children care-givers in providing more comprehensive and effective care for their older kin that is inspired by love and traditional values.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants who shared their valuable time and care-giving experiences in responding to our questions. A special word of gratitude to Heritage Foundation in Hyderabad, HelpAge India (Tamil Nadu and Telangana Branches), ARUWE in Chennai, and Senior Citizens Associations in Chennai and Hyderabad for connecting us with the study participants.

Author contributions

TAJJ designed the study, collected and analysed data, and wrote the manuscript. AM and AK also designed the study, supervised data collection and analysis, and wrote the manuscript. LA gave inputs on the analysis.

Financial support

This work was supported by EP Nuffic, the Netherlands (Grant # 30.95.6343-N), as part of Netherlands Fellowship Program in the year 2016.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE), India (#MUEC003/2017).