Introduction

Health systems invariably face limitations arising from the finite availability of resources. The inability to address every potential health need introduces the requirement for resource allocation, which can vary according to different degrees of transparency and level of allocation. The spectrum of resource allocation includes decisions made explicitly and implicitly, thus ranging from policy-driven and transparent allocation through to an ad hoc resource allocation by individual clinicians who have been entrusted with a resource.Reference Oei 1 , Reference Spector-Bagdady, Laventhal and Applewhite 2 Additionally, health resources are allocated across three levels: the macro-, meso-, and micro-level. This spectrum includes allocation at a budget, policy, and societal level as well as allocation occurring within the clinician-patient dyad.Reference Beirão, Patrício and Fisk 3 –Reference Willging, Jaramillo, Haozous, Sommerfeld and Verney 7 These foundational principles contribute to the complexity of scarce health resource allocation at baseline.

As specialist services are restricted by resource availability, there is increasing awareness of resource allocation decision-making in intensive and critical care. Recent emerging insights into decision-making regarding resource allocation at the individual patient level in critical care have highlighted the impact of patient, physician, and environmental factors.Reference Bai, Fugener, Gonsch, Brunner and Blobner 8 –Reference James, Power and Laha 11 This emerging research identifies that clinician-driven resource allocation is responsive to several contextual factors including the characteristics of the patient, resource availability, systems and policies, and individual clinician characteristics.Reference Bai, Fugener, Gonsch, Brunner and Blobner 8 –Reference James, Power and Laha 11 However, it is not clear how these findings and knowledge translate to other contexts, including humanitarian health response contexts.

Humanitarian crisis settings and complex humanitarian emergencies introduce challenges not otherwise faced by established health systems, such as disasters concurrent with critical resource shortages, conflict and other forms of violence, and political collapse. 12 These factors introduce resource scarcity that can impact every core health function, to a scale and degree not seen routinely in developed health systems. A recent systematic search of the literature and formulation of an evidence gap map demonstrated core resource allocation principles detailing experiences of resource allocation in health responses in humanitarian response settings.Reference Horn, Ranse and Marshall 13 In this same review a critical lack of structured research and evidence was available to understand or inform allocation decision-making regarding scarce health resources in humanitarian settings.Reference Horn, Ranse and Marshall 13 The nature of resource scarcity and complex challenges, in addition to the sparsity of research specific to scarce health resource allocation in humanitarian response settings, necessitates targeted exploration of this phenomenon.

Research Aim

The aim of this research was to identify factors that impact or inform decision-making regarding the allocation of scarce health resources in humanitarian response settings by exploring clinicians lived experiences.

Methods

Design

This study arises from a larger body of research into Scarce Health Resource Allocation in Humanitarian Response Settings (SHARE-HRS). The overarching project consists of several independent layers of analysis unified by a cross-sectional exploratory qualitative design. The findings reported here arise from the inductive thematic analysis layer and represent a unique and independent contribution.

Participant Sample

Participants were purposively identified and recruited for their ability to contribute to the exploration of health resource allocation in humanitarian settings, that is, having had first-hand experience in at least one health response to a humanitarian crisis. Participant recruitment was guided by the contribution of the data to the overall research project and terminated upon achieving adequate participant power and information power, meaning both the sample and produced data were able to adequately support and justify the emerging findings.Reference Thorne 14 –Reference Suri 17 This approach to recruitment termination requires more robust reflective practice and justification compared to aiming to achieve or report data saturation.Reference Thorne 14 –Reference Suri 17

Data Collection

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted remotely (via Microsoft TeamsTM) and were recorded to facilitate manual transcription. Prior to conducting data-generating interviews, a pilot non-data-generating interview was conducted. No significant change to the interview guide (Supplemental File 1) was prompted by the pilot interview. Conducting interviews, manual transcription (word-for-word transcription from audio file to text file), and repeated passes of the resulting transcripts provided the necessary familiarity with participant narrative to facilitate analysis.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted in an inductive thematic manner derived from the approach described by ColaizziReference Colaizzi, Valle and King 18 and operationalized by BeckReference Beck 19 and Wirihana et al.Reference Wirihana, Welch and Williamson 20 On review of the completed transcriptions, statements relevant to the health resource allocation were manually extracted into analysis tables. Each extracted statement was considered for its meaning in the context of the research phenomenon and a derived meaning was formulated. Derived meanings were aggregated into clusters according to their nature and relationships with other derived meanings, then clusters were aggregated to allow for overarching themes to emerge from the data. Overarching themes were then utilized to inform a textural description of the focus phenomenon as it pertains to decision making.

Ethical Considerations

Participation in the research was voluntary and only after participants provided informed consent. No rewards or financial compensation were offered in exchange for participation. Potentially identifying information was redacted for confidentiality and anonymity. Ethical approval was provided by the Human Research and Ethics Committee of Griffith University (Ref: 2023/281).

Results

In keeping with maximum variation sampling, the 17 recruited individuals represented a broad scope of participant characteristics (Table 1). Interviews lasted an average of 52 minutes, resulting in a total of 887 minutes of recorded data.

Table 1. Summary of participant characteristics

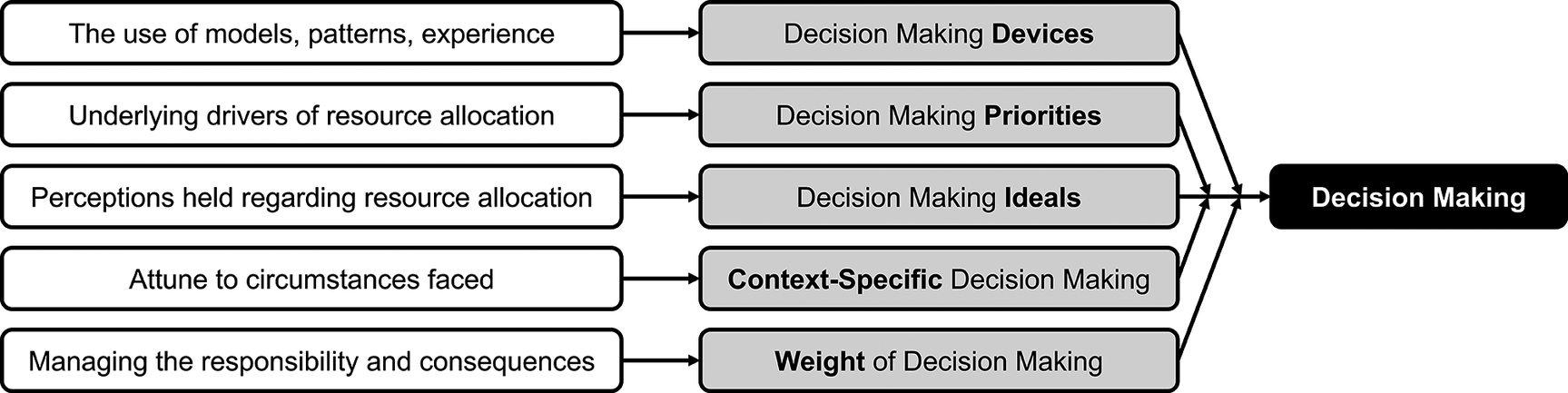

Thematic analysis of data specifically related to decision making revealed 5 themes: (1) devices; (2) priorities; (3) ideals; (4) context; and (5) weight. A graphic representation of these themes, as emerging from the data, is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Inductively derived themes of decision-making.

Decision-making Devices

The theme of Devices is grounded in reflections in which models, patterns, or clinical experience were utilized to inform decisions. The specific devices available to individuals were shaped by their role, degree of engagement in active decision making in routine clinical roles, and clinical experience and acumen. In instances where decisions seemed similar between usual practice and the humanitarian response, core devices were described as remaining mostly consistent with usual practice, just tailored to the setting and relevant factors.

“I think the process is absolutely the same, but what factors go into that decision-making process are different … I want to get the most for the resources I have. But what influences that will be different from place-to-place…” (P10)

When faced with resource allocation discussions, decision-making was performed as an active approach while certain decisions were made using a more pattern-based device featuring a somewhat reflexive link between presentation and resources allocated.

“Someone comes in with cancer – it’s ‘paracetamol and sorry’. If someone comes in with malaria – you put them on an IV … If someone comes in with [tuberculosis], you treat it; if someone comes in with [multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis], then you don’t know and you just treat them …” (P6)

Decision-making was also informed by implementing protocols and a desire to participate in the development of protocols to support standardization as a device to address challenging decisions.

“… when I left, they were putting some of those protocols together in the compound. And it was a group of those doctors and nurses involved in those chats literally sitting around the table going and pulling resources from their individual countries …” (P1)

Decision-making Priorities

The theme of Priorities is grounded in reflections on the priorities that underpinned decision-making and what health care workers sought to achieve by their decisions. Key priorities included sustaining “big ticket” items, allowing futility to self-limit resource use, and a range of other outcomes including hope, validation, clinical impact, and efficiency. These priorities drive resource allocation, such as the priority of addressing immediately faced needs over potential future needs driving decisions to allocate resources as available, or conversely the priority of maintaining availability driving patient movement from the service.

“… you would see that it would start to deplete, you try and get more in – but it was just trying to fill that need. There was no forward thinking like ‘what’s tomorrow going to bring?’, it was for now …” (P1)

“… in reality, there … have been occasions where we were running short of intensive care beds, we knew that there were operations coming up and therefore patients would have to be moved.” (P15)

Clinicians also prioritized clinical impact and thus these decisions were driven to select patients for care in accordance with the likely impact achievable within the faced resourcing parameters.

“… I will always try and keep as close an eye as possible on the patients that we have prioritised for the resource based on the fact that we think that he or she has the greatest change of survival and basically the greatest benefit from the treatment we can provide.” (P10)

Respect for clinical futility, as a slightly different priority, also influenced decision-making, particularly in terms of justifying resources not being allocated, alleviating tensions around not allocating resources, or assisting in mitigating the impact of patient deaths.

“There was another lady that [sic] was dying … you know, ‘she’s gonna die anyway if I didn’t meet her today; … I can give [her] a half empty asthma puffer to help but what about tomorrow?’. So, they’re not ‘tragic cases’.” (P1)

“There were sad cases that we could not save. Cases of cerebral malaria, that has a 25% mortality even with the best treatment available – so it is something that you expect to happen and you don’t feel guilty.” (P3)

“… there was a risk he was going to die – but if I was not helping him, he was already dying.” (P14)

Decision-making Ideals

The theme of Ideals arises from clinicians holding specific beliefs in relation to resource allocation and how it ought to be done. Ideals around what should influence decision-making included that security should not impact resource allocation, that allocation should be driven by clinical status alone, extra-clinical personal considerations should not impact decisions, and that decisions should seek to “do no harm.”

Ideals felt to be grounded in ethical conduct and practice emerged with implications for the decisions being made. Ethical discourse served as an important guide or means for justifying decisions, implicating this ideal in the indiscriminate allocation of resources.

“If someone’s clearly the soldier and an antagonist in the situation and they come into a hospital and there’s [sic] patients that they have been responsible for harming, then it’s unfortunate and it’s uncomfortable; but, ethically, as a health provider, you absolutely cannot cherry pick what you’re going to do and you don’t let that alter your management. We know that’s fundamentally unethical.” (P6)

The ethical principle or idea of “do no harm” drove decision-making around individual resource use and was used to justify decisions as they were being made, particularly when decisions were potentially incongruent with what would have been acceptable or routine in non-humanitarian response settings.

“… you know as anaesthesiologists and all physicians, it’s always ‘first do no harm to the patients’, right? … Would that do no harm? You have to also then look at if I do nothing, is that going to do harm?” (P7)

“Like the young lady that we had to amputate in Haiti, I think many would be like ‘there’s no way we could do this amputation out in the open with an air hockey amusement park table’. … You do nothing, then you are doing harm to that patient.” (P7)

Weight of Decision-making

Finally, the theme of Weight reflects the difficulties faced when performing decision-making. Decision-making has been performed with a lack of existing guidance for decision makers, those who carry responsibility for decisions that become necessary. Clinicians making allocation decisions are perceptive of and impacted by the individualized nature of decision-making.

“So, in the disaster situation, it’s up to the individual. There are probably individuals who may say ‘no, we can’t do anything’ and you hope that someone else can do something and that’s totally fine – that may be your comfort level …” (P7)

Faced with challenging resource allocation decisions, shared decision-making can be sought out to utilize the expertise of others and thus share the weight or burden of making decisions.

“Sometimes when there were these cases, we could even refer to a referent at a desk in HQ but it was not systematically done. But, I would discuss, if I had no access to a reference on a specific specialty, I would reach out to a colleague from a university or from my years of clinical practice …” (P3)

“We had the management team … When we sat down for a meeting relating to medical issues, like medical camps, then they were there handy to advise on what to do; so, I and the director, our work was to just mobilise and ensure that resources are available and well taken care of.” (P4)

Depending on the professional scope and expertise of individuals, deferred decisions may become sought out, in which the responsibility for a decision is transferred to another. This occurs where decisions take on a nature or scope that more closely aligns with another individual (for example, the medical officer) or a figure that helps dissolve the weight carried by the individual clinician.

“Oh, that’s not true either though because I’ve got a big heart … I personally have had to, not defer it on, but say ‘I can’t make that decision’. So, I often have had to, on a mobile or with the doctor pull them aside and say, ‘look, this and this is going on, I can’t make this decision …” (P1)

Context-specific Decision-making

Context-specific decision-making reflects that decisions are not made in a vacuum but rather must occur within challenging contexts that may challenge existing perceptions. There were resource allocation contexts in which no decision was perceived as necessary, whereas in other contexts decision-making was demanded due to factors including the balance of risk and safety against clinical urgency.

“… we did draw a line in the sand initially because one hospital did not have the appropriate machines or monitoring systems or things like that. We did say ‘no, we can’t work here; we need to wait a day until you can get this and this for us’. But it’s hard to do when life or death is on the line – you do whatever you have to do. … So, life-and-death versus controlled, that’s a completely different thing.” (P7)

Contextual factors that brought about a need for active decision-making included the broader clinical needs of potential patients and thus the preservation of resources in response to what is expected according to the unfolding event.

“… I would also advocate for refusing the really, really low acuity jobs because we were one of a number of NGOs but were probably one of the only few that were medically capable and had the expertise to manage someone who might be unwell …” (P8)

Additionally, the context may range from “home vs humanitarian setting” through to the bedside with the patient. The theme of context therefore introduces a diverse and complex range of circumstances, nuances, and challenges with an impact on the nature of decisions and how they must be made.

“We need to be [conscious] of what we can do and what we cannot do in that situation. [At home], I can push a bit more on a patient, I can intubate the patient, I can put on monitoring… Maybe in an African context, that is my barrier and I will not go towards that because what next? …” (P11)

“You’d see some wild-looking tumour pathologies … even if we know what it is, we can’t do anything with that information. So, we are going to ignore it and we are going to treat the symptoms.” (P17)

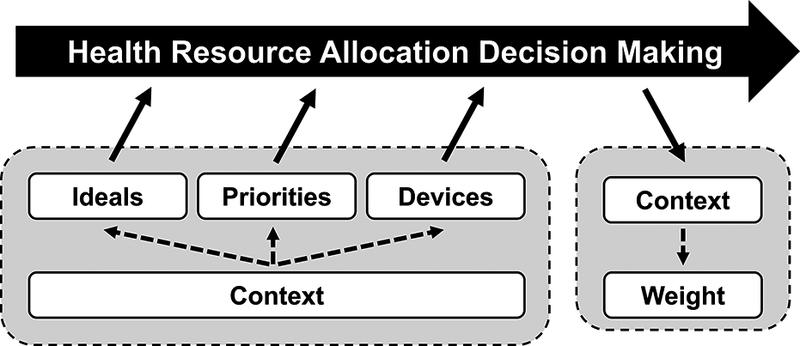

SHARE-HRS Decision Making Model

Considering the themes and their descriptions, a structural description of the phenomenon of decision making emerges (Figure 2), named the SHARE-HRS Decision Making Model due to its origin within the broader project. Decision-making is taken here to reflect a process in which the output is a resource allocation decision, thus the process that results in resources being allocated. Ideals, priorities, and devices are critical inputs for decision making, each heavily influenced by or embedded in the faced context. Although related, they are conceptualized here as independent inputs, as they can differ in their concordance or discordance in response to the specific contextual factors faced. In addition to the decision or resource allocation being a key output, the weight of decision making is a contextually mediated output that rests with the clinician, while the decision made also modifies the broader context; therefore, there is a conceptual link between decision making and weight via the context as an intermediary.

Figure 2. Structural description of decision-making.

This structural description has important implications for research as factors requiring further and targeted research; however, a proposed application of the Decision Making Model at the operational or practical level is demonstrated as an illustrative example (Figure 3). In this example, the Decision Making Model can assist in formulating a pre-mission or operational briefing statement explicitly detailing organizational standards and expectations surrounding scarce health resource allocation in humanitarian response settings.

Figure 3. Illustrative example briefing informed by the Decision Making Model.

Discussion

The marked gaps in existing literature mean that this research, and the produced SHARE-HRS Decision Making Model, is novel in its focus, structured approach, and consolidation as a model within the humanitarian health research landscape. Despite this, the core themes of the model can be identified as woven through existing accounts of health resource allocation in humanitarian response settings. For example, Civaner et al.,Reference Civaner, Vatansever and Pala 21 with a focus on ethical challenges, discuss experiences of triage and treatment guidelines (devices) being rendered insufficient or problematic when brought to disasters from other settings (context), as well as identifying the prioritization of certain populations (for example, the priority of delivering care to children) as emerging as controversial. Durocher et al.,Reference Durocher, Chung, Rochon, Henrys, Olivier and Hunt 22 also with a focus on ethical challenges, reported that the underlying focus of resource allocation (priority) was challenged and shifted over time due to the changing circumstances faced (context). The themes of the SHARE-HRS Decision Making Model also echo throughout discussions in the literature, including those related to the following: tensions between ethical perspectives regarding the treatment of civilians (ideals) and operational necessities (priority) by CeresteReference Cereste 23; commitment to maximizing the benefit of resources (priority) and a dynamic non-concrete approach to resource allocation (devices) by DanielReference Daniel 24; and commitment to addressing the potential greater need over the immediately presenting need (priority) by Sloand et al.Reference Sloand, Ho and Kub 25 The identification of these themes in existing accounts of health resource allocation in humanitarian response settings lends support to the model and establishing the model within the existing although scarce, fragmented and primarily anecdotal, evidence.

There is similar agreement between themes in the model and scarce resource allocation beyond humanitarian response settings, particularly in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. Health systems and academia sought to rapidly develop protocols or triage algorithms to guide clinical decision-making; thus there was an emphasis on identifying or developing formalized decision-making devices in the form of pandemic triage protocols.Reference Christian, Wax and Lazar 26 –Reference Maves, Downar and Dichter 28 Although based on a small number of participants, in some research a preference was identified for decisions to be made the same way as business-as-usual (devices) with increased recognition and support surrounding the burden (weight) of making decisions on a pandemic scale.Reference Horn 29 This lends further support and contextualization of the themes of devices (triage protocols vs pre-existing individualized schemas), context (pandemic versus business-as-usual), and weight (additional burden in pandemic contexts) within the model from other contemporary settings of resource scarcity.

Additionally, there has been significant discussion around the ideals and priorities that ought, or ought not, to inform decision-making of health resources, often with an overlay of ethical discourse.Reference Weismann and Holder 30 –Reference Laventhal, Basak and Dell 32 Such discussions around utilitarianism, egalitarianism, and other philosophical or ethical principles reflect consideration of which ideals are acceptable. Considering the themes identified in this research, these discussions also highlight the close relationship between ideals and priorities while also drawing attention to the divide between these themes and devices. For example, the utilitarian ideal of achieving the greatest good for the greatest many was often cited as a guiding principle in pandemic response plans, and maximizing quality-adjusted life-years was promoted as one relevant utilitarian priority; however, having a clear guiding ideal and priority does not inherently provide the device by which these can be achieved. While this topic is worthy of targeted research and specific consideration on its own, this does lend further grounding and justification for the relevance of the identified themes both within and beyond humanitarian response contexts.

Through extracting, defining, and organizing the themes of the SHARE-HRS Decision Making Model, this research offers a conceptual advancement within humanitarian health response literature. The model serves as a conceptual model and source of common nomenclature addressing scarce health resources and supports the need for future research that strengthens connections between the model and existing or emerging constructs in disaster and humanitarian health literature. Future research should also build upon the model to further understand each theme as a decision-making variable, both independently and as themes interconnected according to the model. The model should also be considered for its practical and operational applications, both proactive (planning) and retrospective (evaluative), such as presented in the illustrative example in Figure 3.

Limitations

Maximum variation sampling, by intent, results in a diverse sample rather than seeking a representative sample. The themes and findings that emerge are therefore significant due to being common across diverse experiences emerging from a diverse spread of roles. Additionally, this research was fundamentally exploratory and utilized inductive methods to allow novel findings to emerge from the data without pre-existing or pre-imposed expectations. These findings and how they informed the SHARE-HRS Decision Making Model are therefore evidence-based and valid but are yet to be subjected to investigation in confirmatory methods. Important next steps for the SHARE-HRS Decision Making Model therefore include context-specific examination and confirmatory investigation, including in relation to applicability in various disaster and resource scarcity settings.

Conclusion

Decision-making that drives scarce health resource allocation in humanitarian response settings is influenced and defined by decision-making devices, priorities, ideals, and the context within which they occur. Additionally, decision-making weighs on those responsible for, or associated with, health resource allocation. The structural description of these themes informed the development of the SHARE-HRS Decision Making Model which provides a structural understanding of these key factors. The presented model is amenable to applications in retrospective reviews and evaluation in both operations and research across broader health resource allocation contexts. It also provides a potential structure for humanitarian response organizations to clearly articulate standards related to scarce health resource allocation. This research therefore makes a novel contribution to the conceptual understanding and a common nomenclature for future research and practice.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2025.10301.

Author contribution

Dr Zachary Horn—conceptualization; methodology; investigation (data collection, interview transcription); formal analysis; visualization (production of graphics and tables); writing (original draft); and writing (review and editing). A/Prof Jamie Ranse—writing (review and editing) and supervision. Prof Andrea Marshall—writing (review and editing) and supervision

Funding statement

This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) scholarship.

Competing interests

None to declare.