Introduction

Canada has a relatively unique model concerning municipal political parties. Local elections are not nationalized, meaning that municipal political parties are not branches of national parties. These formations avoid positioning themselves clearly on the left–right spectrum, conveying the image of an apolitical municipal scene devoid of ideological differences and over-valuing consensus (Lucas, Reference Lucas2024; Bherer and Breux, Reference Bherer and Breux2012). Such characteristics also tend to undermine these formations’ credibility as a party, especially as the number of municipal political parties remains relatively low compared with the number of municipalities. Indeed, only two provinces, British Columbia and Quebec, officially recognize them, and Alberta introduced a pilot project in 2024 for the creation of municipal political parties in the cities of Calgary and Edmonton (Alberta Municipal Affairs Ministry, 2024). The province of Quebec has the largest number of municipal political parties in the country, and an estimated 43.1 per cent of elected officials are members of a municipal party (Ministère des Affaires municipales et de l’Habitation, 2022). In this province, Montreal was the first city to establish political parties, which is why we chose it as our case study.

In the literature, be it about Quebec or Canada, municipal political parties are poorly documented. The parties’ often short longevity makes them difficult to grasp, notwithstanding some exceptions, such as Vancouver’s Non-partisan Association (NPA), founded in 1923 (Fillon, Reference Fillon, Martin and Geser1999), which has presented candidates as late as 2022. Overall, the conditions under which Canada’s municipal political parties emerged and remained on the political scene remain largely unknown. The few works that examine them fall into three categories. The first category questions their definition as parties (Quesnel-Ouellet, Reference Quesnel-Ouellet and Lemieux1982; Lightbody, Reference Lightbody1971; Joyce and Hossé, Reference Joyce and Hossé1970). The second compiles yet other works, mostly in English, which analyse the dynamics of the partisan space (Clarkson, Reference Clarkson1971; Mévellec and Tremblay, Reference Mévellec and Tremblay2013; McGregor et al., Reference McGregor, Lucas, Erl and Anderson2024). A third category of studies analyses the ideologies and platforms of these formations as well as their electoral gains (Belley, Reference Belley2003). None of the studies focus on the topic of elections as such, limiting themselves to a descriptive account of one or two elections at the most. Nor do any of these studies offer a longitudinal view of these formations or consider the institutional and electoral contexts in which they evolve. In this context, the city of Montreal offers an intriguing case for analysis, having hosted numerous political parties since the mid-twentieth century. To bridge these gaps, we have formulated our main research question as follows: What factors contribute to the emergence and longevity of municipal political parties in Montreal, and how does the influence of these factors vary depending on the type of political party?

To answer this question, we implement two research approaches at once. The first develops a systematic description of the institutional and electoral context in which these formations emerge. The second identifies and characterizes the partisan space, covering aspects such as the types of actors behind these parties, the degree of coordination of this formation and the nature of the electoral platform developed.

In doing so, our article offers three major innovations in the analysis of municipal political parties. As discussed, studies of municipal politics in Canada have long been neglected by political scientists (Mévellec, Reference Mévellec2021). The latter tend not to consider political parties as “real” given their ephemeral lifespan, the death of the party following the resignation of a leader, their virtual disappearance between elections and the absence of ideological positioning. At the same time, the few attempts made by national political parties to operate at the municipal level have ended in failure (Fillon, Reference Fillon, Martin and Geser1999). Our first innovation is to take these findings at face value and adopt the terminology of “minor party,” as coined by Pedersen (Reference Pedersen1982): “an organization—however loosely or strongly organized—which either presents or nominates candidates for public elections, or which, at least, has the declared intention to do so” (5) and “as mortal organizations bounded by a lifespan” (1).

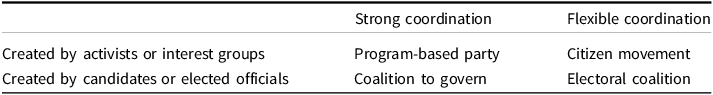

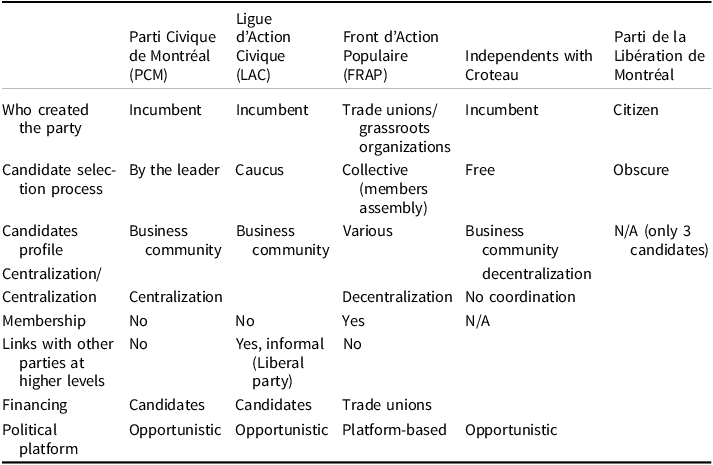

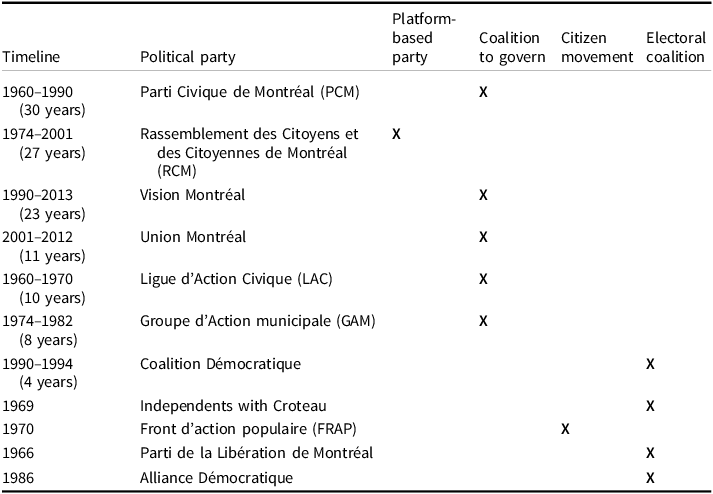

Further, and related to the first point, research suggests that these parties are so diverse that they cannot be classified. This has given rise to multiple designations over time, such as “civic parties” and “people’s parties” (Quesnel and Belley, Reference Quesnel and Belley1991); “notable parties” and “mass parties” (Gagnon-Lacasse, Reference Gagnon-Lacasse1982); and “candidate alliances,” “liminal parties,” “formal parties” and “ghost parties” (Erl, Reference Erl2022). Yet, these designations do not apply over time. On the basis of a typology developed a few years ago for the provinces of British Columbia and Quebec (Couture et al., Reference Couture, Breux, Bherer, Breux and Couture2018), we posit that parties can always be distinguished on the basis of two main criteria: the types of actors behind their creation (elected officials or activists) and their degree of coordination (weak or strong) (Table 1); This constitutes our second innovation. Although simplistic, this typology is able to classify parties over time.

Table 1. Typology of Municipal Political Parties

Source: Couture et al., Reference Couture, Breux, Bherer, Breux and Couture2018: 96.

Finally, the emergence of municipal political parties has been associated, from the outset in 1960, with a response to a specific social context. Quesnel and Belley see the emergence of such parties as a response to “the new conditions of urban life and the forms of management of this reality” (Reference Quesnel and Belley1991: 19; our translation). It is also important to mention that most Canadian municipal partisan systems are not welcoming to the entry and emergence of new parties. This is not the case with the municipal level in Quebec and Montreal, where municipal parties have been able to pry open the municipal structure. However, to the best of our knowledge, the institutional, electoral and partisan context of Canadian municipal parties has never been systematically studied. Here, our study provides an initial portrait of the factors likely to influence the presence and lifespan of these formations; this constitutes our third innovation.

Our research contributions are relevant given that the presence of such formations on the Canadian municipal scene is growing and is not neutral. Political parties influence the legibility and structuring of the political scene insofar as they are likely to influence electoral participation as well as the professionalization of municipal elected officials. This applies especially to the province of Quebec, where more women than men run under the label of a political party. That said, this influence can vary according to the organization and platform of these groups. This uniquely Canadian and Quebec context where municipal political parties are not a response to national branches of political parties (Otjes, Reference Otjes2020; Copus et al., Reference Copus, Wingfield, Steyvers, Reynaert, Mossberger, Clarke and John2012) and have no official ideological orientation (Boogers and Voerman, Reference Boogers and Voerman2010) warrants further investigation.

Our study focuses on the Montreal partisan system from 1960 to 2001. We chose this period for several reasons. Firstly, municipal political formations first emerged in 1954 in Montreal with the Ligue d’Action Civique (LAC), followed by Sarto Fournier’s Ralliement du Grand Montréal. However, the electoral system of the time was complex: “prior to 1960, the Montreal electorate was divided into three groups: class A was made up of homeowners, class B of tenants (male heads of households) and class C of intermediary bodies and associations such as universities and unions. The coexistence of councillors from three different electoral bodies paralysed the council” (Lustiger-Thaler, Reference Lustiger-Thaler1993: 473; our translation). After the 1960 election, however, the provincial government announced its intention to end the city’s complex electoral system. It was also at this time that Jean Drapeau created a new political formation, rallying several members of the LAC behind him: the Parti Civique de Montréal. As Lustiger-Thaler reminds us: “The entry of political parties into City Hall in 1960 and the advent of a system inspired by British parliamentarianism and the American system [….] were the starting point for the growth and expansion of municipal government in Montreal” (Reference Lustiger-Thaler1993: 474; our translation). At the other end of the spectrum, we chose the year 2001 because, following the mergers that shook up Montreal’s electoral system, the 2001 election ushered in a renewal of political formations. Based on the creation of an electoral database from 1960 to 2001 and a systematic press review, we show that two types of factors are likely to influence a party’s longevity. One type is external to the parties (provincial institutional, economic and political context), and the other type is internal to the parties (strong internal coordination, charismatic leader and ability to survive after the leader’s departure). Furthermore, in Montreal, two types of parties tend to outperform other parties in terms of longevity: the governing coalition and the platform-based party. More broadly, our analysis highlights that municipal political parties in Montreal can very well endure over time and that, although the city’s independent municipal parties are not simply offshoots of local branches of national parties, as they are elsewhere, its partisan space is not “purely” apolitical either.

Methodology

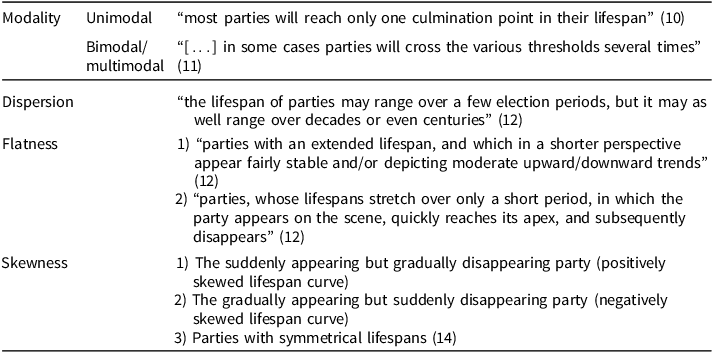

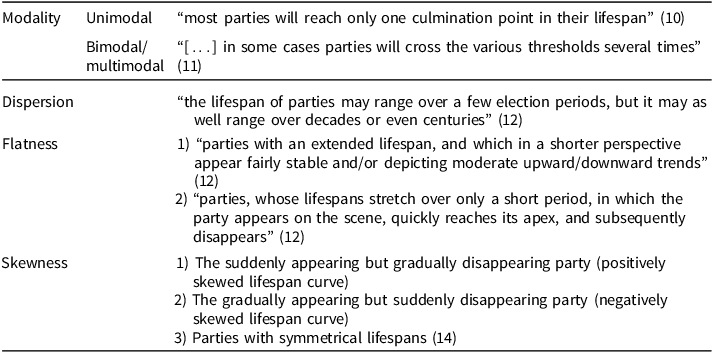

To answer our question, we begin with the work of Mogens Pedersen. Pedersen’s starting point is that parties are mortal organizations whose strength will vary according to electoral periods. In the course of its existence, a party will pass a certain number of thresholds. The first is “declaration,” when the party publicly declares its existence and proceeds to campaign. The second threshold is when the organization meets the necessary conditions to present candidates for election (“authorization”). The third threshold, “representation,” is reached when the party wins seats. The final threshold is that of “relevance.” At this stage, the party wields influence in the party system and has the potential to become the party in power. According to Pedersen, these thresholds, albeit forming a continuum, mark phases in the life cycle of parties and their attributes. Going further, Pedersen points to the fact that we do not know at the outset what each phase will look like, resulting in a curve presenting the characteristics discussed in continuation (Table 2).

Table 2. Dimensions of a Party Lifespan According to Pedersen (Reference Pedersen1982)

Building on this idea of a party’s lifecycle, our aim is to identify the factors that might influence the lifespan of a municipal party. For this, we draw on the work of Vincent Lemieux on the Quebec Liberal party (Reference Lemieux2005), the work of Quesnel (Reference Quesnel-Ouellet and Lemieux1982) and our own previous work (Couture et al., Reference Couture, Breux, Bherer, Breux and Couture2018).

Three dimensions: institutional, electoral and partisan

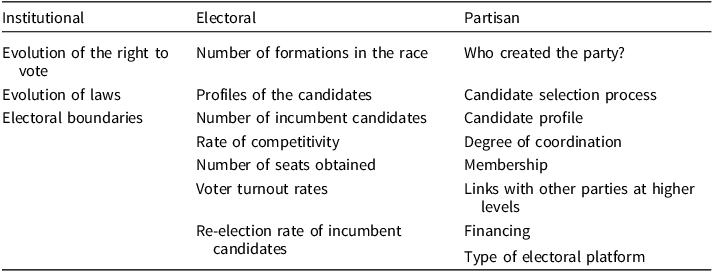

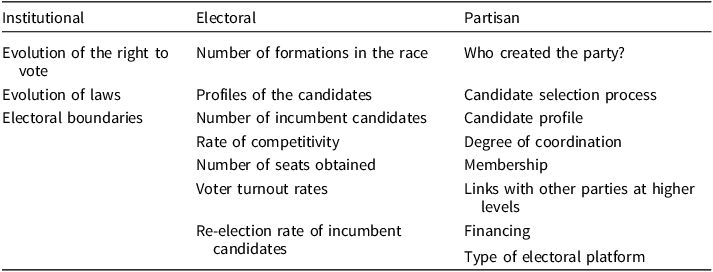

The aim of analysing the institutional space (Table 3) is to identify any conditions that facilitate the emergence, maintenance, domination or defeat of an electoral group. This involves analysing all legislative changes and their evolution so as to understand their possible role in the existence of political parties. We consider this to be necessary in view of Quebec’s young municipal democracy (Bérubé and Breux, Reference Bérubé, Breux, Breux and Mévellec2024) and the complexity of the municipal electoral system.

Table 3. The Three Dimensions Under Study

The study of the electoral space, for its part, aims to position the formation within the electorate, including in comparison with other existing formations, and to assess the candidates, the elected representatives and the renewal of the political class. These criteria will enable us to qualify the lifespan as theorized by Pedersen (Reference Pedersen1982) (thresholds of declaration, authorization, representation and relevance).

The partisan space, finally, comprises the set of elements related to party organization, candidate selection, links with parties at higher levels of government and internal party cohesion. This analysis will enable us to qualify the types of parties that make it to the race. The dimensions of the grid are based on the typology we developed earlier:

When party discipline is rigid and the party is the creation of an external group, we consider it to be a citizen’s movement. It is the existence of a more formalized organization in program-based parties that allows us to make the distinction between program parties and citizens’ movements. Additionally, if the party is the creation of elected officials or candidates and if the party line is rigid, then we consider it to be a governing coalition. Finally, when party discipline is relaxed, then it is considered an electoral coalition. The party life between two elections allows us to make the distinction between these two types of parties. (Couture et al, Reference Couture, Breux, Bherer, Breux and Couture2018: 96)

We take up and build on characteristics put forward by Quesnel (Reference Quesnel-Ouellet and Lemieux1982) (candidate profile, financing, membership and so forth) to allow us to better grasp not only the organization of the party but also the selection of the leader and their importance in the organization. In Quebec, municipal political parties are known to be weakly structured, with little “partisan activity outside election periods. Frequently created with a view to the polls, they are often little more than electoral machines organized by and around the leader” (Breux and Mévellec, Reference Breux and Mévellec2024: 298; our translation). As Lemieux (Reference Lemieux2005) suggests in his book on national parties and their transformations, highlighting the place occupied by the leader also means determining the concentration of leadership, including the party’s mechanisms for limiting that concentration.

The study of the platform space aims to determine whether the party is more intent on setting up a program (platform) than on responding to citizens’ expectations. Conversely, an “opportunistic” party, to use Lemieux’s term (Reference Lemieux2005), would be one whose objective is to respond to citizens’ expectations. More specifically, a party focused on the realization of a platform will not be sensitive to the expectations of public opinion and will maintain compliance with that platform, while an “opportunistic” party will aim to orient its proposals towards the expectations of its electorate: “A programmatic party tends to stick to the governing options listed in its platform, whereas an opportunistic party is more sensitive to feedback from other parties regarding its governing options, and thereby more likely to modify these options” (Lemieux, Reference Lemieux2005: 140; our translation).

Case selection and data collection

We chose to focus our analysis on the case of Montreal as it saw the emergence of the first municipal partisan formations in Quebec and inspired other municipalities to follow suit (Quesnel and Belley, Reference Quesnel and Belley1991). Our investigation began with 1960, with the birth of the first political party, the Parti Civique de Montréal (PCM), and ended in 2001 with the amalgamation of the city. As a reminder and for the sake of clarity, Montreal mayors are elected by direct universal suffrage by the entire population, and its city councillors are elected at the district level by a first-past-the-post system.

The scope of the data to be collected and collated was indeed significant. We drew on two types of sources. Firstly, we systematically searched the newspapers of the time for the partisan affiliation of the candidates running, as well as their proposals/platforms, profiles and votes obtained. In Quebec, electoral data have only been centralized since 2001. And while there is a project tracking all electoral results since the first Montreal elections, it does not indicate the candidates’ affiliations. In this way, we built a specific electoral database for Montreal from 1960 to the present day. Into this we integrated a consideration of the history of Montreal’s electoral and institutional framework, given the many changes which Montreal had gone through during this period.

Municipal Political Parties in a Non-partisan Context

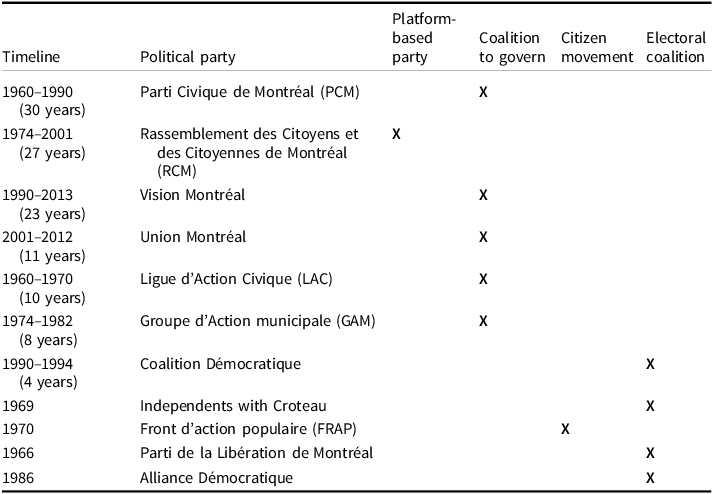

The electoral dynamics of the 1960–2001 period can be divided into three phases: 1960–1970, 1970–1994 and 1994–2001. These divisions follow trends in the municipal parties in power.

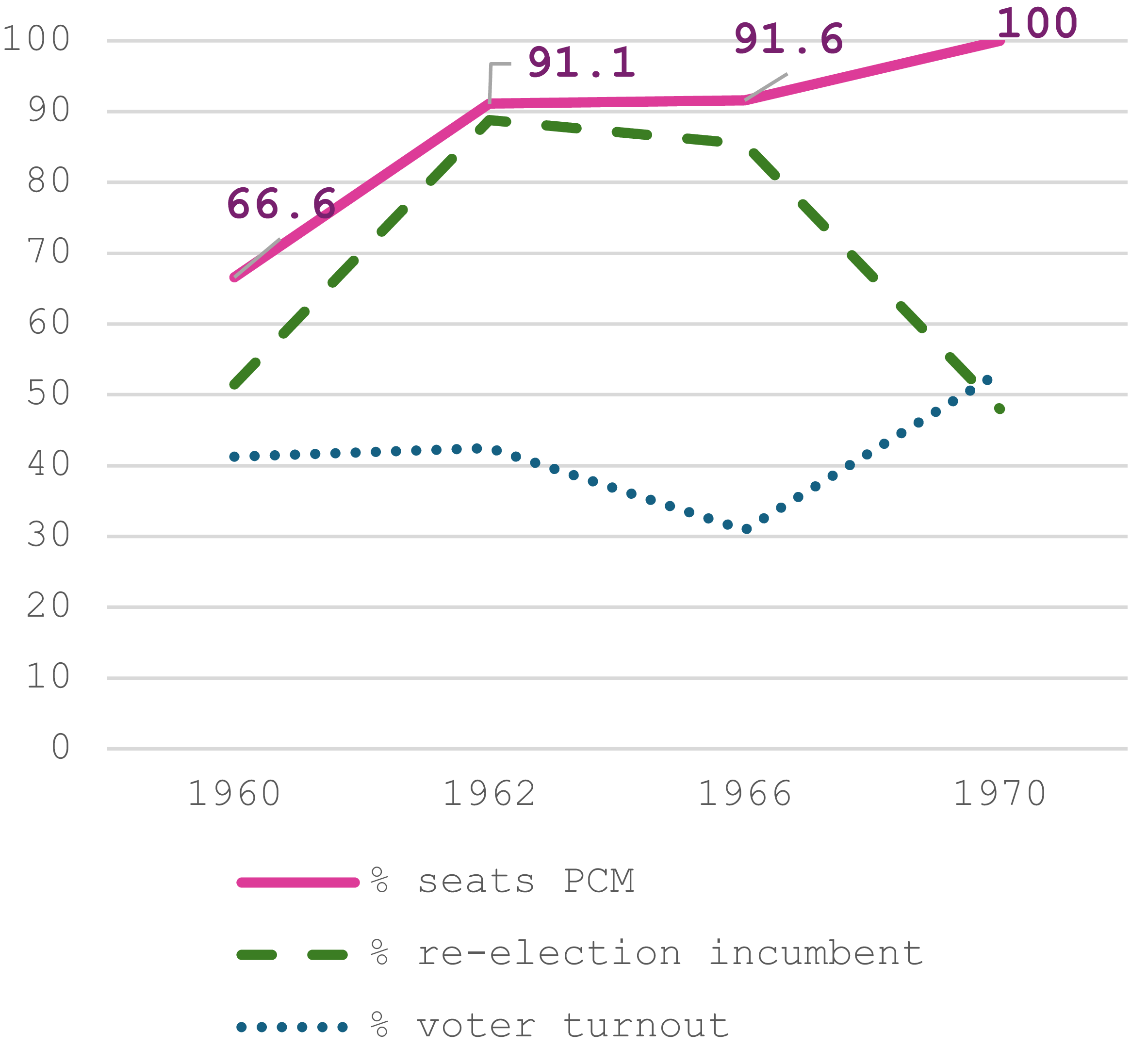

1960–1970: Jean Drapeau’s Parti Civique

Before discussing municipal political parties, it is worth recalling that the 10 years spanning 1960–1970 was a period of institutional upheaval, mainly in terms of the division of electoral districts and the number of positions to be filled. In 1968, property qualifications for candidates were lifted, and in 1970, the right to vote became universal. These upheavals reflected the instability of the institutional and electoral framework (Figure 1). In 1960—partly because of the complexity of the system at the time—there were three classes of councillors: classes A, B and C, elected by three types of electorates (owners, tenants and associations). Tenants eligible to vote from 1960 onward had to have paid their taxes and were referred to as “tax-paying tenants.” In this sense, the property qualifications remained. The arrival of universal suffrage in 1970 almost doubled the number of voters: “The number of Montreal voters rose from three hundred and eighty thousand sixty-eight in 1966 to six hundred and ninety-eight thousand three hundred and sixty-nine in 1970” (Dagenais, Reference Dagenais1992: 40; our translation).

Figure 1. Institutional and Electoral Framework and Party System from 1960 to 1970.

In terms of the party system, the number of parties varied between two and four during this period.

Between 1960 and 1970, eight different groups were present on the Montreal scene. In this study, we will focus on those with the best chances of winning for each election.

The Parti Civique de Montréal was founded in 1960 by Jean Drapeau: “In the weeks leading up to the 1960 election, Jean Drapeau took everyone by surprise. In September, he left the Ligue d’Action Civique and, with the help of seventeen city councillors, founded the Parti Civique” (Dagenais, Reference Dagenais1992: 37; our translation). Drapeau ruled the party with an iron fist. He selected, on his own, candidates on the basis of their reputation as well as on and what they could bring to the party (Quesnel-Ouellet, Reference Quesnel-Ouellet and Lemieux1982: 282). Each party member had to contribute between CA$1000 and CA$2000 to the party (Fillon, Reference Fillon, Martin and Geser1999). There was no real room for dissent, as the head of the party centralized everything. The platform was opportunistic, insofar as it was very reactive to the demands of a certain segment of the population. More specifically, according to the researcher Francine Gagnon-Lacasse: “Although their platforms may not seem very ideological, these parties ascribed to a precise conception of local life, namely the one promulgated in the United States during the 1930s. This ideology is based primarily on administrative efficiency” (Reference Quesnel-Ouellet and Lemieux1982: 12; our translation). Drapeau, despite his conservative origins, is recognized as capable of conversing with people of all provincial political stripes (Raboy, Reference Raboy1978). Most of the party’s candidates were businesspeople and merchants.

In 1960, the Parti Civique ran in opposition to the Ligue d’Action Civique, which Jean Drapeau had initiated some 10 years prior. The Ligue had an internal structure with general meetings, a board of directors and committees and a clear nomination process. Each member had to contribute CA$1000 and might at times be expected to pay for certain of the Ligue’s expenditures (Patenaude, Reference Patenaude1962: 16). The Ligue did not run candidates for mayor but nevertheless put forward 56 candidates for the 66 positions to be filled in 1960. However, in 1960, Lucien Croteau, a member of the City of Montréal’s executive committee, ran for mayor with a group of independents. His candidature presented an informal coalition rather than a party, being independent. It was also the Parti Civique’s main opponent, even if short-lived. In the subsequent election, in 1962, the Parti Civique ran against the Ligue d’Action Civique alongside another formation, the Parti des Citoyens. As neither of these opponents survived, the Parti Civique was virtually alone in the 1966 election race, with the Parti de la Libération de Montréal fielding only three candidates. The 71 percent of candidates fielded by the Parti Civique were elected by acclamation.

Between 1960 and 1970, the Parti Civique clearly dominated the electoral arena. Securing the position of mayor in 1960, the party’s dominance peaked in 1970 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Domination of the Parti Civique de Montréal (1960-1970).

This domination was made possible by a lack of viable, credible opposition: Many parties were formed and dissolved with each passing election, while others often lacked the capacity to put forward enough candidates for the number of positions to be filled. Moreover, it was not uncommon during this period for mayoral candidates to run without the support of a political group or for groups to not put forward a mayoral candidate. So, despite being a multi-party system in theory, in practice only one party had the means to take and remain in power. It should be noted that the re-election rate of incumbents during this period was very high.

Mayor Drapeau was the mayor of major projects. After building the city’s subway system, he embarked on the Olympic Games, the costs of which far exceeded those forecasted. Protests began mounting. Since the early 1960s, citizens’ movements had sprung up in the poorest neighbourhoods, often among tenants who did not, then, have the right to vote. In the early 1970s, poverty and the cost of the Olympic Games led to the emergence of the Front d’action populaire (FRAP), a movement that originated in the trade union movement.

The organization and structure of FRAP were decentralized. Created by trade unionists, the movement had a strong platform called Les salariés au pouvoir! and was more flexible and largely decentralized. It represented a credible opposition to Drapeau and was well received in the press. Nevertheless, it ran candidates only in certain districts and had no candidate for mayor, though fielding four women (Richard, 1970). Its candidates’ profiles were varied (trade unionists, cab drivers, secretaries and so forth) (La Presse, 1970). However, Drapeau, intent on staying in power, took advantage of the tense provincial climate caused by the actions of the Front de Libération du QuébecFootnote 1 (FLQ) and associated FRAP with the FLQ. FRAP, in turn, failed to properly defend itself and to deliver consistent messages to the electorate. With municipal elections held under martial law, Drapeau then swept all the seats, eliminating FRAP’s political chances. The election was a veritable plebiscite for Drapeau and his team. FRAP nonetheless obtained 18 per cent of the vote, which at least testified to the emergence of an opposition (Comby, Reference Comby2005).

In conclusion, the 1970s were marked by the presence of a party with a strong desire and ability to stay in power. Created by an incumbent elected official, it was highly centralized and aimed to respond to the demands of the electorate (composed predominantly of homeowners during this decade). In this context, the emergence of a viable opposition was more difficult, as shown by the number of formations that did not last over time. FRAP nevertheless marked a break with the past: It was a highly decentralized formation with flexible overall coordination and a platform, as well as members with different profiles (Table 4). The dominance of the Parti Civique de Montréal was also facilitated by the institutional context: Both electoral franchise and electoral distortion gave the party an advantage that it was able to capitalize on (Le Devoir, 1960). Jean Drapeau also took advantage of a tense social context to put an end to any hint of opposition. However, the removal of electoral franchise allowed another party, the FRAP, to make inroads.

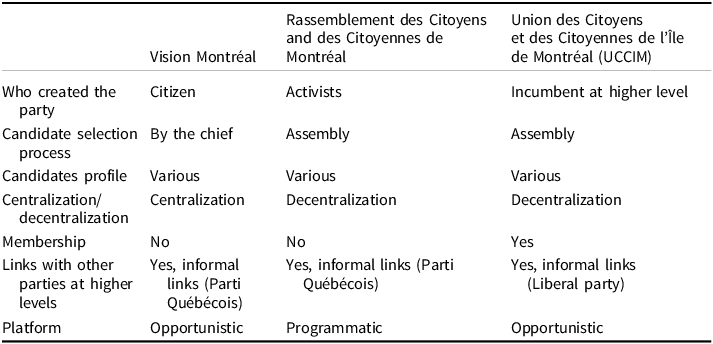

Table 4. Party Structure, Organization and Financing (1960–1970)

From 1970 to 1994: the Rassemblement des Citoyens et des Citoyennes de Montréal

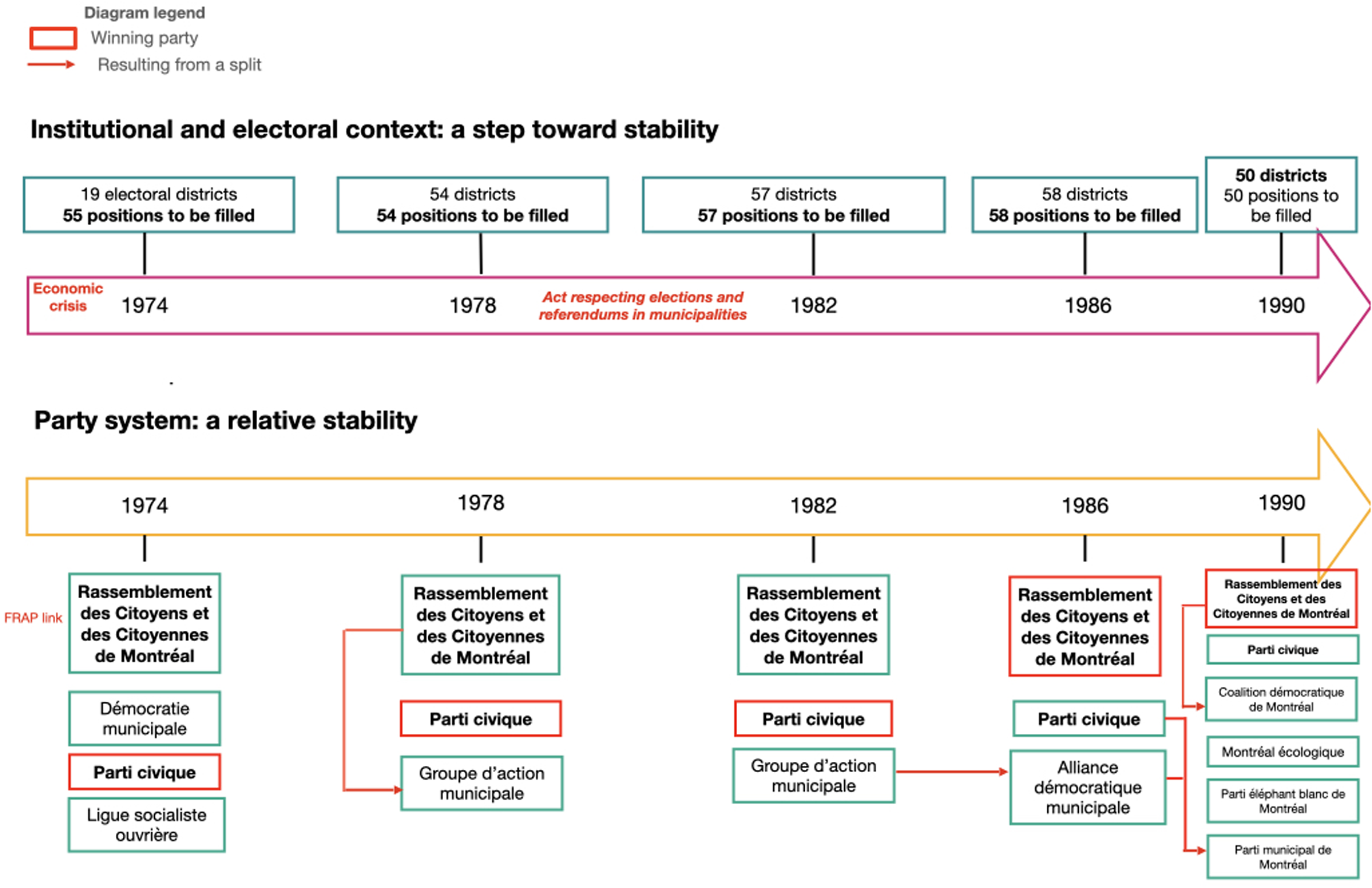

Between 1974 and 1994, the institutional framework stabilized, thanks to the adoption between 1978 and 1982 of a series of provincial laws contained in the Act Respecting Elections and Referendums in Municipalities. And although the electoral framework was continually being modified with a view to limiting the representation of electoral districts to one municipal councillor per district, the party system remained relatively stable, with two political parties present throughout this period: the Rassemblement des Citoyens et des Citoyennes (RCM) and the Parti Civique de Montréal (PCM) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Institutional and Electoral Framework and Party System 1974–1990.

From 1970 onward, despite Drapeau’s victory, opposition to him continued to mount, recomposing itself in response to a changing provincial context. Leading up to the provincial election in 1973, the Parti Québécois (PQ) became more prominent. Following its defeat in 1973, Parti Québécois activists then founded, together with other groups, the Rassemblement des Citoyens de Montréal (RCM) in 1974 as a way to strengthen its local presence (Thomas, Reference Thomas1997).

With a decentralized structure, multiple bodies (congress, executive council, local associations, general council and so forth) and many members, the Rassemblement’s aim was to establish a platform based on information obtained at local assemblies. The RCM gradually gained media visibility and made several public appearances. In 1974, the party put forth a leader of its own, a working-class priest by the name of Jacques Couture. He campaigned in Montreal neighbourhoods, dubbed “les petites patries,” achieving RCM leadership of some of them while, in others, at least forcing Jean Drapeau to take a stand on issues his party had previously neglected (Croteau, Reference Croteau2008). The 1974 elections had three parties in the running. The RCM fielded as many candidates as there were positions to be filled, and 10 women stood for election (compared with none for Drapeau). The party succeeded in undermining Drapeau’s self-confidence, getting 15 councillors elected in 1974. While the party’s youth gave the city council a somewhat dilettantish and disorganized image, it was above all an internal split—some call it a duel between pragmatists and idealists (Thomas, Reference Thomas1997)—which led to the departure of several members and the creation of a new formation, the Groupe d’Action Municipale (GAM). While the GAM had no clear structure, the party’s statutes “provide for the establishment of district associations as well as a district council, to meet twice a year. The council is to be made up of the presidents of the district associations, members of the ‘parliamentary’ wing and the executive council, composed of five people to whom the candidate for mayor will be added later […]” (Le Devoir, 1978; our translation). The GAM’s platform resembled that of the RCM. In addition, it had a star candidate, a Liberal senator, Serge Joyal. Importantly, GAM fielded as many candidates as there were positions to be filled. Thus, in 1978, three formations faced each other, all with the same number of candidates. Overall, the GAM’s presence obscured the message of the RCM, which was also struggling to find a new leader.Footnote 2 Compounded by the fact that the RCM’s new leader, Guy Duquette, lacked the necessary stature (Le Devoir, Reference Quesnel-Ouellet and Lemieux1982), and that the RCM’s actions on the municipal council were disorganized and marked by filibustering, the RCM lost support among the electorate. It was the PCM that emerged largely victorious from this confrontation between former and present members of the RCM. According to Quesnel, the adoption of the law on the financing of political parties indirectly favoured the PCM since “candidates who obtain more than twenty per cent of the votes cast are entitled to be reimbursed a sum equal to half the expenses incurred […] PCM candidates claimed to have spent a quarter of a million dollars during the 1978 election campaign. The electoral success thus earned them a substantial reimbursement” (Reference Quesnel-Ouellet and Lemieux1982: 288; our translation), which is not the case for opposition parties.

It was the arrival of Jean Doré in 1984—through a by-election—that enabled the RCM to take off. Importantly, Jean Doré, who had the ear of the Parti Québécois, then in power at the provincial level, played a significant role in the law on the financing of political parties, allowing municipalities to assist political organizations in getting their message across. Jean Doré enjoyed the backing of the RCM, having had a presence in the party since its founding. The first party nominated him as a candidate for mayor in 1982, an election where he would not be elected. Subsequently, the RCM pulled out all the stops to make its candidate known. “Jean Doré, leader of the RCM, was undoubtedly the revelation of the 1982 campaign. Previously unknown, he made a remarkable breakthrough on the electoral scene” (Beauregard, Reference Beauregard2005: 426). In 1986, the context had changed. Jean Drapeau and the GAM were not standing for re-election. Although three parties nevertheless ran, only the PCM and RCM proposed as many candidates as there were positions to be filled. The PCM began to embrace a more social vision of Drapeau’s platform. The final challenger was a marginal one, the Alliance Démocratique, composed of former members of the GAM and other marginal parties.

Once the RCM took power, the party distinguished itself by implementing a great number of reforms and public consultations, among them a vast reform of the administration and democratization of the municipal scene. At the next election, some elected RCM representatives left the party (accusing the RCM of not having kept certain promises) to create the Coalition Démocratique.

A similar scenario unfolded in the Parti Civique, where two former elected officials created the Parti Municipal de Montréal, which included English-speaking members such as Nick auf der Maur, a former GAM member. The Parti de Montréal had a platform and members and presented as many candidates as there were positions to be filled. As a result, four parties were vying for power in the 1990 election. The RCM was elected for a second term.

During the 1974–1994 period, the two most powerful parties—the PCM and the RCM—were two very distinct organizations. The RCM was a highly decentralized and structured party which put the realization of its platform, drawn up with its members, at the heart of its actions. At the same time, as in the decade from 1960 to 1970, new parties emerged and vanished between elections. However, splits led former elected representatives of the two main parties to create their own formations: This was the case for the GAM and the Coalition Démocratique (some of whose members came from the RCM) and also for the Parti Municipal de Montréal, whose members came from the Parti Civique de Montréal and the GAM (Table 5).

Table 5. Structure, Organization and Financing of Competing Parties (1974–1990)Footnote 3

During this period, both the monopoly of the Parti Civique and the economic crisis led to the creation of a third party (Pinard, 1973), the Rassemblement des Citoyens et des Citoyennes de Montréal (RCM). The fact that Jean Drapeau was not seeking re-election seems to have helped the RCM win. While the RCM pushed for a law governing municipal political parties, the funding it brought to the parties primarily benefited the Parti Civique. The fact that the RCM is platform-oriented seemed to be undermining its internal cohesion, as evidenced by the various splits.

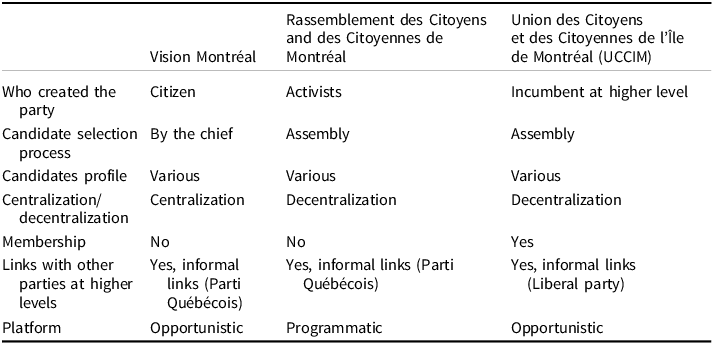

1994–2001: Vision Montréal and UCCIM

Between 1994 and 2001, the institutional and electoral framework once again underwent major upheaval. At the provincial level, the Parti Québécois ordered the amalgamation of municipalities, greatly modifying Montreal’s electoral system (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Institutional and Electoral Framework and Party System 1994–2001.

In 1994, a new challenger appeared: Vision Montréal. This party was founded by Pierre Bourque, a civil servant who had been involved with the RCM and to whom the RCM had, in fact, offered party membership. Pierre Bourque enjoyed a certain notoriety among the population thanks to the botanical garden he had designed. However, a conflict erupted between the RCM administration and Pierre Bourque over the establishment of a Société des musées et des sciences naturelles de Montréal: “This bureaucratic upheaval was played out against a backdrop of power struggles between what was undoubtedly the city’s most popular civil servant—Pierre Bourque, head of the Botanical Garden and spiritual father of the Biodôme—and an administrative apparatus that would have preferred to see Bourque stepping back a bit” (L’aveuglement municipal, 1992; our translation) (Figure 4).

Vision Montréal was centralized around its leader, yet its process for nominating candidates remained obscure. The party’s internal organization resembled that of the Parti Civique, and former mayor Jean Drapeau congratulated Bourque on his victory. In the 1994 election, the Vision Montreal platform revolved around making Montreal a green city and meeting the needs of its citizens. For the RCM, however:

things were not going very well […] [the party] has lost four councillors since the beginning of fall 1993. These recent defections came in the wake of the five others that had occurred since 1990. Although it still held a majority with 31 councillors, the RCM was doing a poor job of concealing its internal quarrels, the demobilization of its members and the wear and tear on its power. (Belley, Reference Belley2003: 102; our translation).

Vision Montréal won the election, which was a major blow for the RCM. Internal dissent, broken promises due to a difficult economic context, opposition from the media and a political platform that struggled to renew itself can explain the defeat. Added to this was the fact that the PQ, which had just been elected to the National Assembly, supported Pierre Bourque, a fervent nationalist, against Jean Doré. The other two formations were those present in 1990: The Coalition Démocratique merged with Montréal Écologique, and “[t]he Parti civique de Montréal, which had merged with the Parti municipal de Montréal in the spring, merged this time with J. Choquette’s Parti des Montréalais” (Belley, Reference Belley2003: 102; our translation).

By 1998, the political game had shifted. The RCM was still struggling to recover from its defeat. Jean Doré had left the RCM and founded a new party: Équipe Montréal. At the same time, the RCM mayoral candidate resigned and joined Jacques Duchesneau’s Nouveau Montréal team. As a result, the electoral offer was split between people who were once united, leaving the way clear for Vision Montréal to win a second mandate. The RCM came in third, ahead of Nouveau Montréal. The RCM’s inability to get back on its feet led it to merge with a newcomer, former Liberal minister Gérald Tremblay and his Union Montréal party. The Coalition Démocratique, for its part, merged with the Union des Citoyens et des Citoyennes de l’Île de Montréal (UCCIM). The 2001 elections had a special flavour in that three parties were pitted against each other. The candidates clashed over the “One Island, One City” concept, and even though it was Bourque who had ignited this idea, it was the UCCIM and its candidate Gérald Tremblay who ultimately won the election. The structure of the UCCIM was decentralized and not as developed as that of the RCM. The third challenger was a marginal one: the Parti Éléphant Blanc. This party, which was not taken seriously by the press, reformed in 1998 under the name Montréal 2000.

The 1994–2001 period was thus marked by the decline of the parties of previous decades and the arrival of parties whose organization and structure resembled those of past formations. During this period, the Parti Québécois’ support for Vision Montréal was one of the reasons (but not the only one) for the RCM’s decline.

The Lifespans of Municipal Political Parties: A Factor of Institutional Context or Economic Crisis?

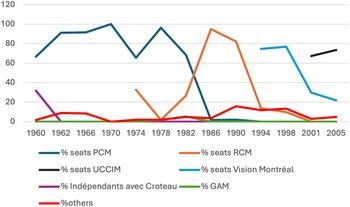

Overall, our historical analysis of Montreal’s municipal political formations reveals a rather eclectic landscape. They present not only a diverse organization and structure but also a variable longevity, with some lasting more than 20 years and others lasting just 1 year. The longest-lived parties were those with a normal lifespan curve as defined by Pedersen (Reference Pedersen1982), being the governing coalition (Parti Civique de Montréal) and the programmatic party (Rassemblement des Citoyens et des Citoyennes de Montréal). Numerous factors contributed to the greater longevity of these two types of political formations, as shown by a detailed analysis of their respective lifespan curves (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Percentage of Seats by Party (1960–2001).

The curves of these two parties resemble each other in terms of flatness and dispersion, indicating a similar longevity with relatively stable rises and falls. The RCM differs, however, in the “modality” dimension (Table 2): The latter was bimodal, with an initial breakthrough, before collapsing and rising again, something the PCM did not experience. These different curves can be explained by a distinct circumstance. When Jean Drapeau created the Parti Civique in 1960, he already had significant experience in municipal politics: He had already been mayor before, founded the party together with 19 former LAC members and had an established rapport with incumbents. By contrast, when the RCM was founded some 14 years later, its members had no such experience. This possibly explains why the party failed to secure more seats in the subsequent election, as represented in the first drop in the curve. The party spent the following years establishing the internal rules and structures it would need to regain power. Thus, the political experience of the individuals who make up the party can be seen as a factor that contributes to the longevity of a party.

How might we explain the fact that only these two types of parties have such a curve, in other words, that they have passed all the thresholds as defined by Pedersen? We posit that it could be attributed to internal as well as external factors. As for the internal factors, the PCM was centralized around its leader Jean Drapeau, while the RCM’s structure was decentralized. Either way, the two formations had strong internal coordination. According to our classification, formations with more flexible internal coordination do not persist over time (Tables 6 and 7). The presence of strong internal coordination therefore seems to be a factor favouring the longevity of these formations. While the degree of centralization of the party organization distinguished the PCM (centralized organization) from the RCM (decentralized organization), our analysis shows that decentralized organization with local structures in each district and activists tends to make the formation more sensitive to dissension and resignations than an organization such as the PCM.

Table 6. Structure, Organization and Financing of Competing Parties (1994–2001)

Table 7. Typology of Montreal parties 1960–2001

Although they operate in different ways, these two formations share the same difficulty in surviving once a charismatic leader has left the scene. The need for a unifying, well-known party leader, regardless of the party’s organization, is therefore inescapable. Drapeau’s strong personality and the concentration of the party’s leadership in his hands enabled the formation to endure over time. According to Dagenais, “the rule of unanimity prevails, both within the executive committee and the council” (Reference Dagenais1992: 39; our translation). Throughout the years, Drapeau’s strong personality was also appreciated by Montrealers, and when he left, the party became weaker. The various leaders who succeeded him lacked his charisma with the public and within the party. The same can be said of Jacques Couture of the RCM, whose travels to the “petites patries” ensured him a certain notoriety and popularity with part of the electorate. His successor Guy Duquette did not have that aura, although Jean Doré, following Duquette, managed to establish himself as a credible leader for the party. Pierre Bourque, of Vision Montréal, likewise had a high profile, thanks to his directorship of the Montreal Botanical Garden, a popular Montreal landmark.

As for factors that are external to the parties, it is the institutional context that weighs in. The institutional context played a significant role in the emergence and existence of municipal political parties. Political actors use it as a lever to bring their formation into being and to endure and to turn it overall to their advantage. During the 1960s, the institutional context clearly favoured the establishment of a political monopoly (Trounstine, Reference Trounstine2008): On the one hand, only homeowners and tenants who had paid their taxes could vote, and on the other hand, there was electoral distortion in the division of districts. This was clearly visible in the 1960 election, where half the districts had a disproportionately large number of voters. In a similar vein, the visibility and emergence of FRAP was buttressed by the introduction of universal suffrage in 1970 as well as the movement’s choice to field candidates only in districts where they could count on support. In the following decade, the RCM likewise turned the institutional context in its favour, working to institute an act on municipal political financing that would enable it (and its opponents) to run for office. The institutional context can also, in some cases, prove to be a hindrance, as demonstrated by the electoral division and the Act Respecting Elections and Referendums in Municipalities.

The second external factor is the presence of an economic crisis. Analysis of the electoral context shows that viable oppositions emerge in crisis situations when there is an absence of an alternative or a political monopoly. When Drapeau’s party encountered real opposition in 1970, with the arrival of the FRAP, it showed teeth to retain power by associating the FRAP with the FLQ. This obliterated FRAP’s chances of winning and paved the way for the birth of the RCM. The economic crisis and general dissatisfaction among the population, as well as the Parti Québécois’s breakthrough at the provincial level, favoured the arrival of the RCM, which positioned itself as a viable alternative to Drapeau. However, it was Jean Drapeau’s diminishing presence and vigour (for health reasons, among other reasons) that bolstered the arrival of the RCM. When the party was nominated for a third term, the fragility of its platform, internal divisions, splits and an economic crisis that prevented it from achieving certain goals were all to have an effect. Vision Montréal remained in power for two terms, mainly owing to the absence of a viable opposition. Our study also reveals defection and party-switching, with many RCM members joining Vision Montréal and many GAM members supporting the Alliance Démocratique. Similarly, the reappointment rates of incumbents point to a modest renewal (except on rare occasions) of the municipal political class.

The partisan system was (and is) not purely “apolitical.” Although Montreal’s municipal parties are not branches of provincial parties, and no candidate campaigns by mobilizing their partisan affiliations, it is not as if provincial parties are absent. However, as Gagnon-Lacasse (Reference Gagnon-Lacasse1982: 10; our translation) points out: “At present, the formation of local parties even seems to be the only common ground that has ever existed between people who are normally adversaries at other levels. Indeed, it’s not uncommon to find Liberals, PQ members, Unionists and Conservatives working in perfect harmony to set up a local party. There are, of course, a few municipal columnists who uncover links between individuals belonging to a provincial or federal political party and certain local parties. However, these links remain unofficial and individual. They take the form, for example, of discreet assistance in the form of human and material resources, or the public endorsement of a candidate or party by a member of parliament or a minister.” In 1982, Jean Doré’s membership of the Parti Québécois (PQ) enabled him to advance legislation on municipal parties. Nevertheless, in 1994, the PQ preferred to support Pierre Bourque. While these endorsements cannot be considered a factor influencing party longevity, given the difficulty of clearly identifying the actual presence, nature and influence of such endorsements, the fact remains that they likely played a role, if only in the eyes of voters who were privy to such knowledge (Lucas, Reference Lucas2020). Similarly, we note that the municipal parties, although apolitical, positioned themselves on a left–right spectrum in relation to each other. For example, the GAM is to the right of the RCM, while the Coalition Démocratique is to the left. All these findings are in line with Lucas’ (Reference Lucas2020) findings on the ideological representation of Canadian municipal politics despite its apolitical claim.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this analysis shows that there are two types of factors likely to affect a party’s longevity. One type consists of factors that are external to municipal organizations but that affect their life: (1) the institutional context, and more specifically, changes in electoral rules (voting rights, electoral boundaries, political party authorization and financing) and municipal mergers and (2) the economic context (economic crises resulting in a change in voter choice) and the political context (the provincial party in power may pass laws that favour one municipal political party over another or offer organizational support to one formation but not another). The other type consists of party-specific factors: (1) strong internal coordination, which can take a variety of forms—centralized, decentralized or in between—and (2) the presence of a charismatic leader who can rally party members. This factor may call into question the relevance of having political parties at the municipal level. If all that is needed is strong internal coordination and the presence of a charismatic leader, why would party activism and a platform even be necessary? Should we agree with Peterson (Reference Peterson1981) that municipal issues do not require a party? This debate over the necessity of having political parties at the municipal level is recurrent, and several authors have highlighted the limitations of Peterson’s argumentation:

[Peterson] claims that the issues faced by local governments are by their nature non-ideological and hence do not give rise to party politics […] [L]ocal politics only deals with the provision of widely agreed upon public goods and their allocation, e.g., the creation of city parks and the decision of where to locate them. These issues, Peterson argues, do not give rise to political disputes because, by their very nature, no one is against public goods. The only type of political conflict in cities, according to Peterson, is about where and to whom to allocate public goods. This, however, does not create partisan competition over platforms and ideas, but instead only creates group and neighborhood-based competition. Despite their prominence, Peterson’s claims are unconvincing. Even if the provision of certain public goods is agreed upon by a wide swath of the population, political parties can debate whether one policy or another is effective in providing the public good. For instance, although crime is widely considered bad and the efficient removal of garbage good, there is no broad agreement about whether to engage in “broken windows” or community policing […] Peterson does not establish why this type of debate could not be the subject of party politics. (Schleicher, Reference Schleicher2007: 422)

While our study does not allow us to determine the relevance or necessity of these formations, the analysis of the differing positions taken by the main competing political parties—such as Jean Drapeau’s Parti Civique de Montréal and the Rassemblement des Citoyens et des Citoyennes de Montréal—reveals distinct stances that go beyond the mere allocation of resources. This is exemplified by the 1974 electoral campaign, discussed in contemporary newspapers as portraying “two conceptions of urban life” (Descôteaux, 1974; our translation). The divergence of visions is aptly reflected in the housing proposals put forward by the PCM and the RCM respectively: one emphasizing the role of private enterprise and advocating for greater municipal authority in housing demolition and the other stressing the participation of citizens in the development of plans and calling for an end to the systematic destruction of housing. In addition, certain issues, such as mobility, have been found to give rise to territorial divides within cities. That dynamic, in turn, induces voters to support a greater variety of parties and underscores the significance of municipal parties in shaping public spaces (Breux and Couture, Reference Breux, Couture, Michael McGregor and Stephenson2024).

Thus, the question of the relevance of political parties at the municipal level may well be less important than that of their internal organization and their capacity to offer platforms that propose distinct and credible alternatives to the issues at stake. What the Montreal experience does show is that the importance of the political platforms varies from one party to another. Indeed, during the period studied, only one party put its platform at the heart of their political project: the RCM. The other parties were either opportunistic (the Parti Civique de Montréal) or opportunistic and programmatic (without the platform being the raison d’être of their party) (UCCIM). The case of the RCM shows that it is possible to have a party whose objective is to implement a platform created and defended by party activists. Another important factor that could be added to the two mentioned above is the organization’s ability to ensure an adequate transition at its head following the departure of a charismatic leader. While a leader may not be the one doing everything, they may well be the unifying force behind the organization. The topic of how a leader influences the future of a party thus merits further investigation.

This study is not without its limitations. For example, it overlooks the importance of the media space in the lifespan of municipal political parties. However, it does offer an initial longitudinal and systematic analysis of independent municipal political parties in the Canadian and, more specifically, the Montreal context, where such formations are neither an anomaly (Boogers and Voerman, Reference Boogers and Voerman2010) nor simply a replica of national parties (Otjes, Reference Otjes2020). Further studies of this nature remain to be conducted, particularly to determine whether our conclusions can be applied to other Canadian provinces. Vancouver, for example, with its markedly different institutional context, would serve as an interesting object of study. The city’s Non-partisan Association (NPA), mentioned in the introduction, has outlasted all other municipal parties—especially those in Montreal—in terms of longevity, boasting a lifespan of 99 years.

Financial support

This research has been financed by the Chaire de recherche du Canada sur les élections municipales (CRC-2022-00117).