1. Introduction

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) introduced 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to address urgent global challenges, such as climate change (United Nations, 2015). The aim of the SDGs is to promote a fairer, inclusive, and sustainable future for all by 2030. The 17th goal, “Partnerships for the Goals”, is aimed at strengthening global partnerships to facilitate the success of the other 16 goals. This goal emphasises the importance of international collaborations between governments, the private sector, civil society, and other stakeholders to mobilise resources, share knowledge, and build capacities for the sustainable development of humanity. However, building and maintaining international collaborations is challenging (Arslan et al., Reference Arslan, Vasudeva and Hirsch2024). The legitimacy and trust required for such collaborations are often difficult to achieve because of political tensions (Bernauer & Böhmelt, Reference Bernauer and Böhmelt2020) and institutional differences between countries and regions, which are difficult to overcome (Leppäaho & Pajunen, Reference Leppäaho and Pajunen2018). While numerous studies have focused on how national-level cooperation fosters the achievement of sustainability goals (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Memon, Memon, Jattak and Shah2024; Islam, Reference Islam2025; Li et al., Reference Li, Ren and Wang2024; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Lu and Wang2020), research on the local-level remains less developed. Although local sustainability initiatives are receiving growing scholarly attention (Atanga et al., Reference Atanga, Wang, Ayambire, Wang, Xu and Li2024; Mahyuni & Syahrin, Reference Mahyuni and Syahrin2021; Shtjefni et al., Reference Shtjefni, Ulpiani, Vetters, Koukoufikis and Bertoldi2024), a critical question remains underexplored: how city-level partnerships can be sustained to overcome obstacles and ensure meaningful environmental outcomes.

This research gap is particularly notable given that, beyond external factors like political tensions and institutional differences, the extant literature suggests that long-term relationships frequently lapse into inactivity due to their inherent inertia (Grayson & Ambler, Reference Grayson and Ambler1999; Oliveira & Lumineau, Reference Oliveira and Lumineau2019). Contrary to this trend, many sister-city partnerships have remained active and effective for decades (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2023), suggesting a need to study the mechanisms that enable their longevity. To understand how effective, enduring city-level international partnerships are developed to address sustainability challenges, this research employs a case study of a highly representative pair: Wuhan and Manchester. As sister cities with a four-decade-long history of collaboration, they provide an illustrative example of successful Sino-British cooperation, specifically in the field of sustainability.

Sister-city partnerships between the UK and China began in the 1980s and were aimed at fostering mutual economic and technological growth. For UK cities – particularly those in the former industrial regions of the north – these partnerships were intended to attract foreign investment. In turn, Chinese cities sought to develop advanced technologies from this collaboration in fields such as medicine, science, and urban development. One of the earliest and most notable sister-city partnerships was between Manchester and Wuhan, which resulted in the first Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) being signed in 1986. These two cities share numerous similarities, including their industrial histories, urban landscapes, and the strong civic pride of their residents. Both cities, once industrial powerhouses, now confront challenges related to urban sustainability and climate resilience. The shared environmental challenges create a strong foundation for their collaboration on urban sustainability. The two cities have entered into a series of agreements on environmental and developmental initiatives (The General Office of Hubei Provincial People's Government, 2018). This partnership has now extended to many strategic areas, including research and innovation, investment and trade, education, and cultural exchange. Remarkably, the partnership has endured despite shifts in the broader UK–China relationship. This enduring partnership between Wuhan and Manchester is exemplified by many collaborative initiatives in sustainable urban development. Notable examples include joint efforts in flood management, smart city innovation, and clean energy development.

Building on this exemplified case, this study identifies key elements essential for developing effective international partnerships that enable cities to address sustainability challenges over time. They are enduring mutual benefits, partnership breadth across various areas, and partnership depth at the grassroots level. Furthermore, the study finds that mutual benefits form the foundation of lasting collaboration. Economic capital from diverse cooperative areas, combined with the emotional capital built through deep grassroots engagement, incentivises stakeholders in both industrial cities to deepen their commitment to their shared objective: sustainable urbanisation. These results contribute to the literature on international partnerships by providing a specific case study that demonstrates how city-level partnerships, such as those between sister cities, can contribute to achieving sustainability goals. This focus on the municipal level offers a distinct perspective from the widely discussed national-level efforts. Furthermore, the study identifies three key factors that sustain long-term partnerships, ensuring they remain active, effective, and resilient against the inertia that can cause them to stagnate. The reinforcing process by which the identified factors adapt and solidify over time also advances the knowledge of why some city-level partnerships are resilient during bilateral tensions, while others are not. It also explains how sustainabilit goals can serve as a shelter for strained bilateral relations at the country level.

2. Literature review

International collaboration is challenging. It is affected by the institutional environment, with institutional distance and political risk being two key factors that significantly influence its success (Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Li and Schotter2020). The first factor, institutional distance – that is, the disparities in regulatory, cognitive, and normative institutions between two countries or regions (Kostova et al., Reference Kostova, Beugelsdijk, Scott, Kunst, Chua and van Essen2020) – encompasses variations in laws, regulations, cultural norms, and accepted business practices. In general, the greater this distance between them, the more significant and negative its effect on cross-country collaboration (H. Zhang & Yang, Reference Zhang and Yang2022). For example, the UK has well-established environmental regulations, but those of China are still in the developmental stage as the country attempts to balance economic growth and environmental concerns. In addition, in the UK, policymaking involves public engagement, whereas China often relies on top-down governance and rapid policy implementation (Couper, Reference Couper2019). Thus, when addressing sustainability issues, city partnerships must navigate and reconcile such institutional differences to achieve common environmental goals.

The next factor, political risk, refers to the potential for political instability and policy changes to affect the success of collaborative efforts negatively (Su et al., Reference Su, Umar, Kirikkaleli and Adebayo2021). The cooperation between the UK and China has been significantly influenced by the political relationship between them. In 1986, Queen Elizabeth II's visit to China marked the first by a British head of state, which underscored the importance of bilateral relations and paved the way for future diplomatic engagements. In January 2009, the British Government issued its first China strategy paper, The UK and China: A framework for Engagement, prioritising China in its foreign policy (Embassy of the People's Republic of China in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, 2010). In 2015, President Xi Jinping's state visit to the UK, during which he met the Prime Minister David Cameron, initiated the ‘golden era’ of China–UK relations, characterised by lasting, open, and mutually beneficial cooperation (“Golden era” of China-UK relations to benefit world at large, 2015). This momentum continued under Cameron's successor, Theresa May. However, the political dynamics have since shifted. Liz Truss considered labelling China a ‘threat’ to the UK (Crylls, Reference Crylls2022), and Rishi Sunak, on taking power, declared an end to the golden era, describing previous economic ties as ‘naïve’ and advocating for ‘robust pragmatism’ (British Broadcasting Corporation, 2022). These fluctuating political dynamics underscore the complex, evolving nature of the UK–China relationship, which directly affects the collaboration between the two countries.

Institutional distance and political risk can influence international collaboration by affecting its legitimacy (Kostova et al., Reference Kostova, Beugelsdijk, Scott, Kunst, Chua and van Essen2020). Legitimacy, in the context of collaboration, refers to the perception that the collaborative effort is appropriate, acceptable, and credible within a given institutional context, and aligns with the norms, values, and expectations of the stakeholders involved (Rana & Sørensen, Reference Rana and Sørensen2021). When two or more parties from different institutional contexts collaborate, stakeholders’ perceptions about the appropriateness, acceptability, and credibility of the collaboration can differ. Such a difference is an inherent challenge in international collaborations, as it affects the legitimacy and, consequently, the success and sustainability of collaborative efforts (Devarakonda et al., Reference Devarakonda, Klijn, Reuer and Duplat2021). Political risks can also affect the legitimacy of international collaborations (Zeng et al., Reference Zeng, Wells, Gu and Wilkins2022; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Li and Wang2024). During periods of favourable bilateral relations, stakeholders are more inclined to perceive collaborations between the two countries as legitimate. Conversely, when such relations deteriorate, stakeholders are more likely to question the legitimacy of collaborations. This fluctuation in perception underscores the vulnerability of international partnerships to the broader political climate.

Further, institutional distance and political risk can also influence international collaborations by affecting trust between stakeholders (Kinder et al., Reference Kinder, Six, Stenvall and Memon2022). Trust in collaboration refers to the ‘actor's willingness to arrange and repose his or her activities on others because of confidence that others will provide expected gratifications’ (Scanzoni, Reference Scanzoni, Burgess and Huston1979, p. 78). However, institutional differences and political risk can both have a significant adverse impact on trust by creating misalignments and uncertainties about expectations. To address the mistrust caused by institutional distance, enhancing communication between stakeholders is essential. Regarding any potential mistrust that may arise as a result of political risks, it is crucial to incorporate these considerations into the formulation of strategic collaboration frameworks. This proactive approach will allow both parties to design and implement effective strategies to mitigate potential political risks and thereby ensure a more robust partnership.

Beyond external challenges such as institutional distance and political risk, scholarly work identifies inertia as a critical internal factor that leads to the decline of partnerships, ultimately rendering them inactive and ineffective (Grayson & Ambler, Reference Grayson and Ambler1999; Oliveira & Lumineau, Reference Oliveira and Lumineau2019). This aligns with the concept of the ‘dark side’ of long-term relationships. As Abosag et al. (Reference Abosag, Yen and Barnes2016) note, even relationships founded on trust are susceptible to negative, unforeseen consequences that can never be fully eliminated. Studies of relational deterioration provide insight into this process, identifying inertia as a key driver (Anderson & Jap, Reference Anderson and Jap2005; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Oh and Swaminathan2006). The phenomenon of inertia can cause partners to become stagnant in their thinking and overly similar, thereby diminishing the relationship's value and innovative potential (Grayson & Ambler, Reference Grayson and Ambler1999; Y. Zhang & Liu, Reference Zhang and Liu2023). This vulnerability is particularly acute in sister-city partnerships, which must actively combat complacency to remain productive over time (Y. Zhang & Liu, Reference Zhang and Liu2023). Supporting this dynamic perspective, Dyer et al. (Reference Dyer, Singh and Hesterly2018) argue that the initial value created through complementarity in sister-city relationships can be weakened by repeated interactions and the development of customised assets, which may reduce the incentive for proactive engagement. Empirical evidence for this divergence in outcomes can be seen in UK–China sister-city pairs: some relationships show no public evidence of activity, while others consistently report fruitful and sustained exchanges. While prior research has largely examined cross-national collaborations on sustainability (Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Memon, Memon, Jattak and Shah2024; Islam, Reference Islam2025; Li et al., Reference Li, Ren and Wang2024; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Lu and Wang2020), attention is increasingly turning to local initiatives (Atanga et al., Reference Atanga, Wang, Ayambire, Wang, Xu and Li2024; Mahyuni & Syahrin, Reference Mahyuni and Syahrin2021; Shtjefni et al., Reference Shtjefni, Ulpiani, Vetters, Koukoufikis and Bertoldi2024). Recently, a growing number of cities worldwide have formed sister-city relationships to collaboratively address the common sustainability challenges they face (Atanga et al., Reference Atanga, Wang, Ayambire, Wang, Xu and Li2024). The sister-city relationship, also known as international friendship cities, represents a formal partnership initiated by local governments to achieve mutual prosperity (Y. Zhang & Liu, Reference Zhang and Liu2023). These partnerships are established based on shared commonalities, such as historical background, economic function, and geographical location, or mutual concerns regarding urban issues and ideologies (Y. Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zhan, Xu and Kumar2020). Although sister-city agreements are formalised by local governments, the development of these relationships depends on the joint contributions of various stakeholders, especially local individuals from both cities, who make collaborative efforts to address the common challenges faced by the two sides (Hu, Natarajan, & Delios, Reference Hu, Natarajan and Delios2021). In this context, the significance of local initiatives in driving successful international collaboration and sustainable goals is increasingly recognised (Ningrum et al., Reference Ningrum, Malekpour, Raven, Moallemi and Bonar2024, Reference Ningrum, Raven, Malekpour, Moallemi and Bryan2023). However, to date, few studies have focused on identifying ways to overcome external and internal barriers and sustain effective partnerships between cities to achieve tangible positive environmental outcomes over time (Mahyuni & Syahrin, Reference Mahyuni and Syahrin2021). Therefore, to fill this gap, this study aims to identify the key elements essential for developing effective international partnerships that help cities address sustainability challenges.

3. Research method

This study employed a qualitative approach to investigate the sister-city relationship between Manchester and Wuhan, using its inductive nature to uncover the key factors that sustain enduring partnerships in sustainable urbanisation. The Manchester–Wuhan partnership was selected as a “typical case” (Seawright & Gerring, Reference Seawright and Gerring2008) because it exemplifies a long-standing, comprehensive collaboration, particularly in addressing urban sustainability challenges over the past two decades (2003–2024). The qualitative approach allowed the researchers to capture the complexities of this relationship by focusing on the dynamic interactions among diverse stakeholders and the multi-layered processes involved in fostering sustainable urbanisation. By combining interviews, participatory observations, and secondary data analysis, this study provides a nuanced understanding of how this partnership has evolved and contributed to broader sustainability goals.

3.1. Data source

This research drew on fieldwork conducted between October 2022 and March 2024. A total of 27 semi-structured interviews were conducted in the UK and two in China, engaging 20 informants who were directly involved in organising or participating in sister-city activities. These stakeholders included government officials at city and regional levels, representatives from investment promotion agencies (at both Chinese national and local, as well as Manchester-based, agencies), business leaders (Chinese and British), university representatives, members of research and training institutions, and participants from the Chinese community, including student representatives. To protect participant privacy and encourage candid responses, interviewees were assured that their information and identities would not be disclosed without their full consent.

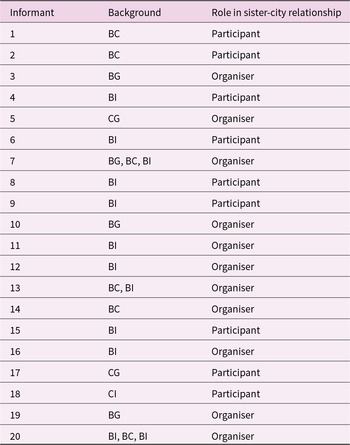

Table 1 provides an overview of the interviewees’ profiles. The research process commenced with identifying publicly available information on the Manchester–Wuhan sister-city relationship to identify key stakeholders with knowledge of its evolution. These potential interviewees were contacted via LinkedIn to solicit their participation. The team then employed snowball sampling, whereby initial contacts recommended further participants. Confidentiality was assured, and no personally identifiable information was disclosed. Tailored interview questions were designed based on each interviewee's specific role in the partnership. Examples of questions include: How was the Manchester–Wuhan sister-city relationship established? Who are the key actors involved in this partnership? What initiatives or programmes have been implemented to strengthen this relationship? How significant do you perceive this partnership to be? What aspects of this collaboration could serve as a model for other sister cities?

Table 1. Overview of informants

Background: BC-British corporate; BG-British government; CG-Chinese government; BI-British institute; CI-Chinese institute.

In addition, this study conducted six participatory observations with Manchester-based stakeholders to deepen its understanding of their activities and interactions. These primary data were complemented by an extensive review of secondary sources, including policy documents, journal articles, and media reports in both Mandarin and English. This triangulation of data sources ensured a comprehensive and robust analysis of the partnership.

3.2. Analysis process

In the data analysis and presentation, which were guided by the methodologies outlined by Gehman et al. (Reference Gehman, Glaser, Eisenhardt, Gioia, Langley and Corley2018) and Gioia et al. (Reference Gioia, Price, Hamilton and Thomas2010), an inductive coding approach was used. Gioia et al.’s (Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013) three-stage coding process was implemented to analyse the data. Phase 1 involved the extraction of statements and quotations through open coding, in which each author independently grouped informant terms. Phase 2 focused on theme development, in which the author team worked collaboratively to define first-order codes by comparing and discussing the results from the open coding process. In Phase 3, conceptualisation took place, where the themes were examined for relationships and patterns and then merged into conceptualised dimensions. The coding process and results are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Analysis process.

4. Results and discussion

The analysis results highlight three key factors that contribute to the success of international collaborations: enduring mutual benefits, partnership breadth across various areas, and partnership depth at the grassroots level. Enduring mutual benefits, such as those associated with sustainable development, indicate political neutrality, which can diminish the impact of political risks and thereby help stabilise the legitimacy of, and trust within, the collaboration. Broad partnerships across various areas refer to the expansion of collaboration from the initial core areas to a wide range of domains. The accumulation and exchange of collaborative experiences across different fields can help strengthen mutual understanding and reduce the institutional distance between the parties. Moreover, the economic and cultural capital accumulated from the past cooperation in different areas motivates stakeholders to navigate a broader scope of cooperation. Deep partnerships at the grassroots level involve more profound, people-to-people cooperation than official intergovernmental collaboration. Such cooperation fosters strong interpersonal trust. This emotional capital can help mitigate the impact of political risks on the collaboration.

4.1. Enduring mutual benefits

The fundamental factor that enables two cities to maintain a partnership on sustainable urbanisation is enduring mutual benefits. Both Manchester and Wuhan have prioritised climate change and sustainable urbanisation as key development and strategic focus areas. The local governments of both cities have devoted ‘a great deal of mutual commitment and effort to achieving sustainable urbanisation’ (Informant 13). For example, they have signed a Manchester–Wuhan Smart Cities MoU in 2015 and another in 2016, a Climate Change and Environmental Protection MoU in 2016, and an MoU on Hydrogen Energy in 2022. Since 2016, cooperation has also expanded to encompass regions between the middle reaches of the Yangtze River and the northern areas of the UK.

The acknowledgement of the importance of sustainability from the UN and the central governments in the UK and China provides ‘a safe space for [the] two cities to develop partnership in climate change and sustainable cities’ (Informant 13). The concept of sustainable cities transcends political boundaries, as it is one of the SDGs set by the UN (SDG 11) for the betterment of all humanity. This socially and politically legitimised topic not only serves to bolster cooperation between the two cities, or even two countries, but also allows them to sidestep political disruptions, even amid periods of strained relations between them as in the case of the UK and China. The best example is when the then UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak signalled the end of the UK's ‘golden era’ relationship with China (Milliken, Reference Milliken2022) but also emphasised the necessity for cooperation with China on certain global issues, such as climate change. Interviewees noted that post-2019, marked by the termination of this golden era and the disruptive COVID-19 pandemic period, the two cities continued to seek avenues for sustained exchanges and cooperation in sustainability. Climate change and new energy emerged as ‘politically safe areas’ to navigate, alongside their long-standing collaboration in other areas over the decades (Informants 7 and 13).

4.2. Partnership breadth across various areas

The maintenance of a long-term partnership in urbanisation is also due to the breadth of the partnership, which helps legitimise the sister-city relationship among a diverse range of stakeholders in both cities. The partnership between Manchester and Wuhan stands out among sister-city relationships between the UK and China because of its comprehensive scope of cooperation. This collaboration spans a wide range of areas, including government training, research and technology, education, cultural exchange, trade and investment, and sports. The shared urgency to address climate issues acted as a catalyst for creating a collaborative platform between the two cities, which also facilitated broader connections between the UK and China. This collaboration brought together an extensive network of diverse stakeholders, enabling the partnership to extend beyond climate issues to encompass economic benefits. The tangible outcomes (e.g., measurable economic gains and successful joint programmes) and intangible outcomes (e.g., knowledge exchange and technology exchange) of these initiatives further motivated stakeholders to deepen their involvement. The breadth of these activities raised public awareness in both cities, thus fostering greater recognition of its significance. Over time, more organisations and individuals became aware of the value of the relationship and expressed a growing willingness to participate in additional sister-city initiatives, which further strengthened the partnership.

For instance, the Manchester China Forum is one of the most prominent organisations facilitating economic cooperation and cultural exchanges between Manchester and Wuhan, as well as between the UK and China. One of the interviewees from Manchester commented that this forum provides critical social capital for businesspeople when they plan to establish a business in Manchester or China. If this Forum had not been established to facilitate substantive business, the relationship between the governments may have only been ‘just … superficial’ (Informant 4). As a formal platform, the partnership also facilitated regular training courses for government officials from Wuhan at the University of Manchester. Through these sessions, these officials gained insights into Manchester's urban development practices, which they later applied to urban development initiatives in Wuhan. A senior official from Wuhan's municipal government reflected on the inspiration gained from Manchester's post-industrial transformation during a six-month training programme in 2006. Through this initiative, young government officials from Wuhan were sent to Manchester to learn about urban regeneration strategies. The official noted, ‘I explored Manchester's methods for industrial transformation. They repurposed factories into spaces for culture, commerce, and innovation, which significantly influenced my ideas for Wuhan's urban tourism strategy’ (Informant 17).

4.3. Partnership depth at the grassroots level

The depth of the partnership is another key factor contributing to the sustained collaboration in sustainable urbanisation, especially during the times when the UK–China relationship deteriorated. Routine people-to-people exchanges (e.g., photo exhibitions and cultural exchanges) create fertile ground for fostering understanding and trust among individuals from the two distinct cultures, thus deepening the relationship from a government-to-government relationship to a people-to-people one. To build social trust and cohesion, both cities strive to integrate elements from Manchester and Wuhan into their local communities. For instance, on the Manchester side, people-to-people links have been identified as one of the three pillars of the Manchester China Forum's efforts to promote investment between the UK and China (Informants 13 and 16). In addition, the Manchester Museum showcases the development of UK–China relations as well as the Manchester–Wuhan sister-city relationship. An exhibition in this museum highlights that environmental protection is the common focus of the two cities and countries. The official website of the Manchester Museum also records the story of ‘Wuhan Wood’, a wooded area of Hough End, which was planted to commemorate the 10-year relationship between Manchester and Wuhan in 1995.

On the Wuhan side, the Wuhan government bestowed the Yellow Crane Friendship Award on a British businessman, whose family has built a relationship with China for six generations, in recognition of his pioneering efforts in building the China–UK relationship and promoting trade between the two countries. During the interview, the awardee stated that he had also hosted children from Wuhan at his parents’ house to provide them with a quintessential English experience. He mentioned that his dream for bridge-building activities between the UK and China centres around personal connections rather than business. He believes that organising cultural exchanges between the young people from the two countries is the best way to alleviate misunderstanding and cultivate trust. Further, he mentioned that he considers Wuhan as his second home because his engagement with China began when he was 10 years old. He also mentioned that the key to maintaining the relationship, in essence, should be ‘people’, not ‘politics’ (Informant 13).

Social trust and cohesion can indeed facilitate proactive actions to identify new cooperation opportunities in urban sustainability between the two cities, especially during challenging times. For example, in 2021, the UK–China Hydrogen Forum was held as the sole commemoration for the 50th anniversary of ambassadorial relations between the two nations in 2022, amid the deteriorating UK–China relationship. An MoU on hydrogen energy cooperation between Manchester and Wuhan was also signed during this event. One of the organisers of this cooperation mentioned that “we just think … we need to do something for [the] UK and China. Since Wuhan and Manchester ha[ve] long-standing cooperation in climate issues, and new hydrogen energy is [a] common future focus for [the] two countries, we decided to initiate the UK–China cooperation in hydrogen energy” (Informant 7).

4.4. How the key factors adapted over time

Based on this analysis, the common, politically neutral needs of sustainable urbanisation form the foundation for a lasting partnership between these two industrial sister cities. Broad areas for cooperation and deep grassroots engagement incentivise governmental and non-governmental stakeholders to invest in the relationship. This investment generates significant economic and emotional capital, which in turn reinforces the partnership and facilitates the pursuit of further common goals. Specifically, broad areas of cooperation provide stakeholders with multiple platforms for engagement across economics, technology, environmental protection, and education. These platforms enable stakeholders to leverage their respective strengths, facilitating mutual learning and complementarity. A prime example is the Greater Manchester–Wuhan Metropolitan Area Economic and Trade Promotion Forum, jointly organised by the Wuhan Municipal Government and the Manchester City Council. This forum served as a platform for both regions to present their industrial advantages and explore specific investment opportunities. The economic foundation of this partnership is a key differentiator. As one informant involved in establishing the sister-city relationship recalled, ‘The Manchester–Wuhan Friendship Agreement was based specifically on economic benefits, especially through higher education, not merely on cultural exchanges. Previous friendship agreement did not have the same base as this one (Informant 5).’ This focus has yielded significant results. As of 2020, Greater Manchester was home to the largest population of Chinese students in Europe, with figures exceeding 10,000 (University of Manchester, 2020). A government official from Wuhan confirmed this success, stating that ‘Education is the most successful area of economic cooperation between Manchester and Wuhan (Informant 17).’ Ultimately, the substantial economic capital generated by this partnership incentivises deeper collaboration and reinforces commitment to common goals, while also acting as a shield against political risks during periods of UK–China tension.

Deep grassroots engagement between the two cities further consolidates common goals by cultivating emotional capital – a resource that not only preserves the friendship but also promotes its institutionalisation. This emotional connection is demonstrated through a mutual willingness to engage in dialogue, patience in resolving misunderstandings, trust in cooperation, compassion during challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic, and a sustained commitment to strengthening bonds despite periods of political tension. This connection is actively fostered through formal, regular activities designed to engage the broader public. A prime example is the photo competition jointly organised in 2020. Themed ‘What is Care?,’ it served the dual purpose of celebrating the 35th anniversary of the Manchester–Wuhan sister-city relationship and alleviating collective pain during the pandemic. The success of such initiatives is evident in their personal impact; as one participant noted, ‘I also brought my daughter to participate … where she found her Chinese pen pal’ (Informant 16). It is through these personal, grassroots friendships that citizens are motivated to voluntarily navigate solutions during difficulties, such as a pandemic or bilateral tensions. This bottom-up problem-solving demonstrates the unique value of city diplomacy, a form of soft power that operates alongside formal state channels. As one informant astutely commented, ‘A sister city is a kind of soft power connection (Informant 14).’ Recognising this profound value, both municipal governments officially acknowledge the contributions of individuals who strengthen this bond. By validating these soft-power initiatives, the governments help formalise the regular celebrations. This process of official endorsement is crucial, as it transforms spontaneously generated emotional capital into a structured, lasting legacy – one that is imprinted on the community and passed down through generations.

4.5. Discussion

Overall, the case analysis of the Manchester–Wuhan sister-city relationship confirms that a sustainable international partnership must be founded upon common goals and mutual benefits, as this alignment is a prerequisite for broadening and deepening cooperation. Crucially, this cooperative process generates two forms of capital that actively reinforce the initial foundation: economic capital (Jarness, Reference Jarness2017) and emotional capital (Cottingham, Reference Cottingham2016). The former, accrued from broad collaborations, enhances the legitimised importance of the sister-city agreement for stakeholders, thereby incentivising further investment. The latter, cultivated through grassroots engagement, strengthens interpersonal bonds, fostering resilience and goodwill. It is this very synergy of economic and emotional capital that empowers the two cities to overcome significant barriers to partnership development. Specifically, this accumulated capital provides the resources and goodwill necessary to navigate external obstacles such as institutional distance and political risks (Kostova et al., Reference Kostova, Beugelsdijk, Scott, Kunst, Chua and van Essen2020; Su et al., Reference Su, Umar, Kirikkaleli and Adebayo2021), as well as internal obstacles like relational inertia, which is overcome by sustaining continuous knowledge sharing and maintaining regular ritualised activities (Abosag et al., Reference Abosag, Yen and Barnes2016; Oliveira & Lumineau, Reference Oliveira and Lumineau2019). Accordingly, these findings advance prior research by addressing a core question: how can city-level partnerships be sustained to overcome both external and internal obstacles and ensure effective environmental outcomes? The results provide a theoretical and empirical explanation for enhancing the resilience and effectiveness of local sustainability efforts (Mahyuni & Syahrin, Reference Mahyuni and Syahrin2021; Ningrum et al., Reference Ningrum, Malekpour, Raven, Moallemi and Bonar2024). Finally, by demonstrating how a local partnership can remain resilient amidst national tensions, the case illustrates the conditions under which such sustained cooperation can serve as a buffer for strained bilateral relations at the country level.

The results also offer important policy implications by providing suggestions on how local governments can develop international partnerships and tackle major challenges. First, the case of the Manchester–Wuhan partnership serves as a meaningful example for cities facing similar climate challenges. Sustainable development goals are politically neutral and less susceptible to geopolitical tensions, which makes climate action an ideal starting point for collaboration. Two cities can not only address common climate challenges together but also extend their relationship to include broader economic and social cooperation. Moreover, this case offers a valuable reference for fostering cooperation between developed and developing regions. By identifying shared priorities and emphasising long-term mutual benefits, cities can initiate sustainable exchanges that promote co-development. Finally, the results highlight the importance of local governments focusing on both the breadth and depth of partnership development. Broad partnerships can attract diverse resources and expertise, which can provide essential support for the successful implementation of cooperative initiatives. However, involving multiple stakeholders, particularly those from varying cultural or industry backgrounds, increases the potential for conflicts. In such cases, fostering deep partnerships becomes crucial, as this helps build trust, enhance mutual understanding, and mitigate potential misunderstandings or disputes. Together, these dimensions strengthen the foundation for effective and sustainable collaboration.

5. Conclusions

By analysing the sister-city relationship between Manchester and Wuhan, this study identifies three key factors that enable international collaborations to effectively support sustainable urban development goals: (1) enduring mutual benefits, which provide long-term incentives for continued engagement; (2) broad partnership scopes across various areas; and (3) deep grassroots engagement, which ensures that collaboration extends beyond formal agreements to become embedded in local practices and community exchanges. The study further analyses how these three factors adapt to and reinforce one another to sustain an effective international partnership. It highlights how the economic and emotional capital generated through this broad and deep cooperation enables the two cities to withstand external barriers, such as political tensions and institutional distance, as well as internal barriers, such as relational inertia.

These findings provide a framework for understanding how cities across nations can work together in a sustained and effective manner to address shared challenges and promote sustainable urbanisation. However, this study has unavoidable limitations that open avenues for future research. For instance, while the Manchester–Wuhan partnership serves as a valuable case study, the findings may not be universally applicable, particularly to newly established sister-city relationships where trust and legitimacy are still nascent. This study does not provide sufficient insight into how such new partnerships can effectively initiate cooperation effectively. Future research should therefore investigate strategies for newly established city partnerships to build productive collaboration on sustainability goals.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all interviewees who participated in this project and the REDEFINE team, especially the Principal Investigator Professor Giles Mohan, and the project manager, Natalie Pollard, for supporting the field trips to Manchester and providing comments on the development of the paper.

Author contributions

Yameng Zhang and Bingqing Zhao contributed to the conceptualisation, drafting, and revision of the paper. Weiwei Chen contributed to data collection and analysis.

Funding statement

The research was supported by the European Research Council (No. 885475), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers: 71902200, 72111530240), the Research Development Fund of Xi'an Jiaotong–Liverpool University (RDF-22-01-028), and the IBSS Development Fund of the International Business School Suzhou at Xi'an Jiaotong–Liverpool University (IBSSDF-1122-54).

Competing interests

There are no competing interests.

Research transparency and reproducibility

This research is a case study based on interview data, and the original interview transcripts are available upon request from the authors.