Introduction

Native to Mesoamerica, lindenleaf sage or Salvia tiliifolia Vahl (Lamiaceae) (Figure 1) is mostly found in tropical, seasonally dry habitat (Kew 2024; Standley and Williams Reference Standley, Williams, PC and JA1973); it has expanded to other parts of the world, including Ethiopia. There, the growth of grasses in rangeland is strongly suppressed by S. tiliifolia (Supplementary Figure S1).

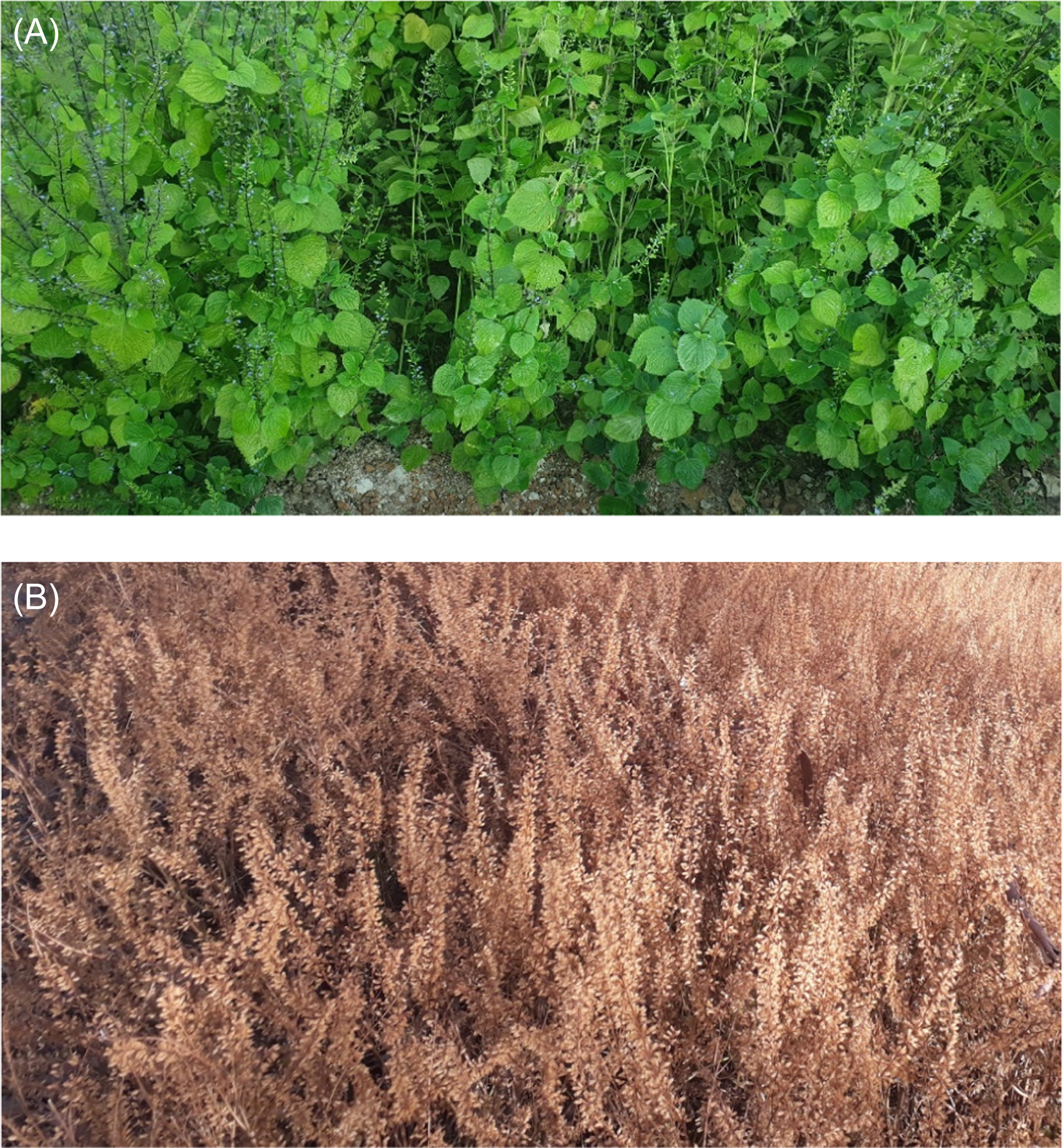

Figure 1. Salvia tiliifolia in Hagere Selam, Tigray, Ethiopia ( 13.6511°N, 39.17583°W, 2,610 m a.s.l.), in (A) flowering (September 25, 2024) and (B) dry stages (November 23, 2023).

In its native Mexico, S. tiliifolia grows as weed in crops, but also in ruderal environments or in the borders and clearings of native vegetation (González-Gallegos et al. Reference González-Gallegos, Castro-Castro, Quintero-Fuentes, Mendoza-López and de Castro Arce2016; Pichardo et al. Reference Pichardo, Vibrans and Lezama2009). In recent centuries, the plant has been transported to other continents, most probably accidentally together with commercial products. Deliberate transplantation of S. tiliifolia seems unlikely, as the species does not exhibit a high ornamental value with its small and short-lived flowers and its weedy behavior (Froissart Reference Froissart2008); for instance, Clebsch does not include it in her compilation of ornamental salvias (Clebsch Reference Clebsch1997). The global expansion of S. tiliifolia has been quite rapid since 1980 (Supplementary Figure S2).

In South Africa, S. tiliifolia has been in the Pretoria area since the 1940s (M van Dalsen, iNaturalist, personal communication, September 23, 2024), but it became a menace in many parts of the country after 2010 (Anonymous 2015). There, it grows in dense stands in both sunny and partially shaded sites; overruns rocky hillsides, roadsides, waste sites, and urban open spaces; and prefers moist places (Anonymous 2015, 2024). It competes with native species and may eventually supplant them (Anonymous 2024). In southern China, S. tiliifolia first appeared in the 1990s and is regarded there as having a high risk of becoming an invasive plant (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Xiang and Liu2013).

Salvia tiliifolia spreads by seeds that drop when the plant dries after the rainy season (Supplementary Figure S3); the seeds may be transported to adjacent places by mammals and birds (Anonymous 2024). In its region of origin, Mesoamerica, it is not considered a major problem, although it occurs as weed in coffee (Coffea arabica L.) orchards (Standley and Williams Reference Standley, Williams, PC and JA1973). Further, it grows in secondary vegetation along roads and at the edges of field crops. It usually does not grow in large numbers. Whereas S. tiliifolia is weeded out from croplands along with other species (Molina-Freaner et al. Reference Molina-Freaner, Espinosa-García and Sarukhán-Kermez2008), there are no targeted weed control programs for it. The situation is different in other continents. In southern China, it was suggested that land managers monitor the species and take action to stop its spread (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Xiang and Liu2013). In South Africa, S. tiliifolia is regarded as a difficult plant to control, because it just keeps growing back and cannot be eradicated until every plant in an area is removed (K Campbell, iNaturalist, personal communication, September 25, 2024); it is therefore recommended that plants be uprooted before they flower and set seed (Anonymous 2015).

In Ethiopia, S. tiliifolia is a recent invasive exotic species, first formally collected and described near Kombolcha in 1996 (Demissew Reference Demissew1996). It is now quite widespread over the Ethiopian highlands. Whereas naturalists (Supplementary Figure S4) and field inventories (Atsbeha Reference Atsbeha2012; Bersisa et al. Reference Bersisa, Wagari and Ishetu2021; Dagne and Birhanu Reference Dagne and Birhanu2023) reported observations on the occurrence of S. tiliifolia, there are few publications about the behavior and environmental preferences of this new invasive species in Ethiopia. Near Harar in eastern Ethiopia, S. tiliifolia was observed to be the dominant herbaceous species in coffee plantations, with highest mean field density and highest relative abundance (32%) (Bersisa et al. Reference Bersisa, Wagari and Ishetu2021). In 2012, the species was reported around Aksum in Tigray (Atsbeha Reference Atsbeha2012). Most studies in Ethiopia (Atsbeha Reference Atsbeha2012; Bersisa et al. Reference Bersisa, Wagari and Ishetu2021; Demissew Reference Demissew1996) explicitly mention that the species has no local name (except “new weed”), which stresses its relatively recent introduction. In the Tigray region, where we studied it, farmers are very worried by this invasive species, especially as they are already coping with the social, agronomic, and environmental impacts of the recent Tigray war (Nyssen et al. Reference Nyssen, Negash, Van Schaeybroeck, Haegeman and Annys2023; Weldegiargis et al. Reference Weldegiargis, Abebe, Abraha, Abrha, Tesfay, Belay, Araya, Gebregziabher, Godefay and Mulugeta2023).

Here we discuss the spread of S. tiliifolia in the Tigray highlands (northern Ethiopia), and efforts to control it. For management options on communal lands, the systematic removal approach is contrasted with the nature-based approach, that is, the restriction of ranging livestock to allow native vegetation to outcompete S. tiliifolia.

Materials and Methods

Plant Traits

Salvia tiliifolia is an erect, short hairy, annual herb with many branched stems, between 20-cm and 1.6-m high (Figure 1). The soft, bright green leaves are arranged in pairs that alternate at a 90° angle from one another. The leaves are simple, ovate with a truncate base, serrate margin, usually with wide teeth. Salvia tiliifolia has tiny blue flowers, upper calyx lip with three veins, corolla 4- to 10-mm long, clustered in spikes up to 30-cm long. The calyx elongates to 10 mm in fruit, enclosing three-angled ovoid nutlets (mericarps), brown and irregularly marbled with a darker tone (Anonymous 2015, 2024; Pichardo et al. Reference Pichardo, Vibrans and Lezama2009; Standley and Williams Reference Standley, Williams, PC and JA1973). The seeds (mericarps) are known as “chía” or “chía cimarrona” and constitute a staple food in Mexico and Central America, next to the cultivated Salvia hispanica L., the species commercially known as chía (Ayerza and Coates Reference Ayerza and Coates2005; Martínez Hernández Reference Martínez Hernández2017; Pichardo et al. Reference Pichardo, Vibrans and Lezama2009).

Field Investigation in Tembien

The research region, the Tembien area is situated between 30 and 120 km west of Mekelle, the regional capital of Tigray. The geology of the area is made up of Precambrian metamorphics, Mesozoic sedimentary rocks, Tertiary volcanics, and Quaternary lava flows (Gebreyohannes et al. Reference Gebreyohannes, De Smedt, Miruts Hagos, Kassa Amare, Hussein, Nyssen, Bauer and Moeyersons2010). A network of deeply incised rivers defines the landscape, with elevations between 1,500 and 2,900 m. A stepped geomorphology was produced by selective erosion as a result of the alternation of different lithologies (Coltorti et al. Reference Coltorti, Dramis and Ollier2007; Nyssen et al. Reference Nyssen, Poesen, Moeyersons, Deckers and Haile2006).

The region is classified as hot semiarid (BSh) by the Köppen climate classification (Peel et al. Reference Peel, Finlayson and McMahon2007). The depth of annual rainfall ranges from 500 to 900 mm (Jacob et al. Reference Jacob, Frankl, Haile, Zwertvaegher and Nyssen2013). Most rain falls in the main rainy season, which usually lasts from June to September. Except for the rainy season, when there are fewer sunshine hours and more rainfall, monthly potential evapotranspiration exceeds monthly rainfall. In one of the major towns, Hagere Selam, yearly rainfall from 2016 to 2022 ranged from 770 to 850 mm, 7% to 18% over the long-term normal. There is a tendency toward increased precipitation and warmer temperatures over time. While the rainy season in 2024 was unusually wet, the drought in 2023 was accompanied by anomalies in rain seasonality (J Nyssen et al. Reference Nyssen, Den Ouden, Bindewald, Brancalion, Kremer, Lapin, Raats, Schatzdorfer, Stanturf, Verheyen and Muys2024b).

In this mountainous area, the farming communities typically use steeper slopes as communal rangeland and more level areas for crops. Free grazing is still the dominant way of feeding livestock and has even expanded due to the Tigray War (J Nyssen et al. Reference Nyssen, Den Ouden, Bindewald, Brancalion, Kremer, Lapin, Raats, Schatzdorfer, Stanturf, Verheyen and Muys2024b). Oxen (Bossp.) are used for farm operations such as plowing and threshing in the small-scale family farms of Tigray, which follow a permanent farming system based on cereals (Westphal Reference Westphal1975). Goats (Capra hircus) and sheep (Ovis aries) are also raised, primarily as a safety net in case of emergencies (Nyssen et al. Reference Nyssen, Naudts, De Geyndt, Haile, Poesen, Moeyersons and Deckers2008). Because crop cultivation has been practiced in Tigray for at least three millennia, the agricultural system has been gradually optimized (Blond et al. Reference Blond, Jacob-Rousseau and Callot2018; D’Andrea Reference D’Andrea2008). After harvest, stubble grazing occurs on cropland as well. Over the past 40 yr, many sloping lands—both rangelands and marginal croplands—have been turned into exclosures, fenced from human and livestock interference (Aerts et al. Reference Aerts, Nyssen and Haile2009; Nyssen et al. Reference Nyssen, Naudts, De Geyndt, Haile, Poesen, Moeyersons and Deckers2008). Linear landscape features, including cliffs and gullies, act as demarcations for these exclosures, with regulations outlining their use. Unlike open grazing land, where those with larger herds tend to monopolize the available biomass, exclosures facilitate communal collection and sharing of grasses, fostering equity within the community. Therefore, in Tigray, the transformation of an area of rangeland into an exclosure is a decision made with considerable deliberation. The natural vegetation is mainly open Olea–Acacia woodland, remnants of the primary dry Afromontane evergreen forests (Asmelash and Rannestad Reference Asmelash and Rannestad2024). The woodlands have a low, single-story, discontinuous canopy and comparatively few tree species. Under this open canopy, grasses and herbaceous vegetation appear during the rainy season (Aerts Reference Aerts, J, M and A2019).

To investigate S. tiliifolia’s rapid spread in Ethiopia’s semiarid Tigray region, and how to control it both on privately managed cropland and on communally owned rangeland and exclosures, we carried out field observations on its distribution and density in various habitats of Tembien between November 2023 and October 2024 (Nyssen Reference Nyssen2024), during both the growing and dry seasons. Forty-three different sites were visited, and open-ended interviews (Albudaiwi Reference Albudaiwi and M2017) were conducted at 14 locations with community members who were present on-site.

Results and Discussion

Salvia tiliifolia Invasion in Tembien

Salvia tiliifolia arrived suddenly but relatively late in Tembien. Raf Aerts (K.U. Leuven University), who made extensive inventories of plant species in Tembien during the period 2001 to 2006, confirmed that this species was absent at the time (personal communication). Farmers commonly mention ca. 2018 as the time of the plant’s arrival around Hagere Selam, where it has invaded rangelands surrounding the town, particularly those with heavy livestock browsing (Supplementary Figures S1 and S5). There are several native Salvia species in the study region with their own local names (Salvia schimperi Benth., Salvia merjamie Forssk., Salvia nilotica Juss. ex Jacq.), which do not have such an invasive behavior (Edwards Reference Edwards, J, JG and Worede1991; Endeshaw et al. Reference Endeshaw, Gautun, Asfaw and Aasen2000; November et al. Reference November, Aerts, Behailu and Muys2002; Seegeler Reference Seegeler1983).

Besides rangeland near towns, we observed S. tiliifolia as a dominant species in nearly all types of grazed areas: open Eucalyptus or Acacia woodlands, formal waste dumps, rocky gorges, coarse alluvial deposits, and sides of footpaths and dirt roads. The plants showed stunted growth under the shadow of trees, however, and seeds do not fully mature in such places. Salvia tiliifolia was conspicuous, but not dominant, in the herbaceous layer in places with less grazing pressure, such as grass strips between cropped parcels, gullies, and banks of ephemeral waterways, as well as on permanently moist places such as banks of grassed waterways and at the edges of a permanent springs. We have not seen S. tiliifolia in rainfed and irrigated croplands, because the species is weeded out at early growth stage. There were no observations in exclosures with dense vegetation. In some pocket areas with various land cover, S. tiliifolia was also absent. The dominance of S. tiliifolia in the herbaceous layer of grazed areas seems an extreme manifestation of the typical mechanism by which invasive species proliferate in rangelands. Browsing livestock continually remove the other herbs while avoiding the unpalatable S. tiliifolia, except for occasional browsing of the infructescence. The low grass and other herbs are further suppressed by S. tiliifolia. Visual observations show that S. tiliifolia is not prevalent in places with reduced grazing pressure, such as exclosures. Quantitative ecological research on this aspect would be appreciated.

Voucher Specimen

Ethiopia, Tigray, Dogu’a Tembien: Hagere Selam, northern part of the town, in secondary vegetation on side of gravel road. 13.65139°N, 39.17250°W, 2,633 m a.s.l. February 5, 2025. Getachew Gebremedhin 1 (LUX herbarium, specimen no. MNHNL178636).

Pathways of the Invasion

Demissew (Reference Demissew1996) suggests that Salvia tiliifolia arrived in Ethiopia through weed-seed contaminated food aid in the 1980s. Grain trade is a known pathway for the introduction of alien plants (Ikeda et al. Reference Ikeda, Nishi, Asai, Muranaka, Konuma, Tominaga and Shimono2022). The fact that S. tiliifolia was first formally observed near Kombolcha, which was a hub for international food aid since the Ethiopian famine in 1983 to 1985 (Augenstein Reference Augenstein2020) supports this interpretation. On the other hand, no extensive surveys have been done, and the plant may also have been otherwise introduced and traveled along roads. Similarly, tree tobacco (Nicotiana glauca Graham), a woody noxious invasive species in the study area (Figure 2), is also said to have come in that period with food aid; yet specimens of the plant had already been collected in a garden in Addis Ababa in 1960 and at Haromaya University campus in 1975 (Nyssen Reference Nyssen1997).

Figure 2. Salvia tiliifolia was weeded out of this wheat field in Hech’i ( 13.64028°N, 39.20472°W, 2,258 m a.s.l.) but left to grow at its edge (November 2023). On the right, Nicotiana glauca.

The pathways of S. tiliifolia spread need to be studied further; the spread over the Ethiopian highlands would logically have followed roads, as dusty lorries transport thousands of seeds of alien plants (Bajwa et al. Reference Bajwa, Nguyen, Navie, O’Donnell and Adkins2018; Khan et al. Reference Khan, Navie, George, O’Donnell and Adkins2018) to suitable environmental conditions. The extent to which multiple traffic and war disturbances may have contributed to this spread is unknown. Further, seed dispersal by runoff water was evidenced in the study area by the presence of S. tiliifolia on sediment deposits in ephemeral streams down from major infested areas.

The wetter conditions in the study area in the last decades and particularly in recent years (J Nyssen et al. Reference Nyssen, Den Ouden, Bindewald, Brancalion, Kremer, Lapin, Raats, Schatzdorfer, Stanturf, Verheyen and Muys2024b), jointly with increasing temperatures, may have created a niche for the species, in line with observations of natural vegetation and crop belts that shift up the mountains in northern Ethiopia (Jacob et al. Reference Jacob, Frankl, Hurni, Lanckriet, De Ridder, Guyassa, Beeckman and Nyssen2017; Nyssen et al. Reference Nyssen, Frankl, Zenebe, Deckers and Poesen2015). The fact that S. tiliifolia spread in South Africa was observed to be strongly subdued in dry years (K Campbell, iNaturalist, personal communication, September 25, 2024) supports this hypothesis.

The large extent and dominance of the plant, with its specific phenology (annual pattern of S. tiliifolia’s life cycle) would be ideal for studies using multispectral satellite imagery with high spatiotemporal resolution. The plant with its dark bluish-green color appears in July, occupies large patches, and grows up to the end of September, when it rapidly decays to homogenous brown-yellowish patches. These colors are unique among the background vegetation and therefore can be picked up through multispectral imagery analysis, which allows detailed studies of its current extent, as well as pathways of diffusion over the last decades.

Salvia tiliifolia Management on Cropland in Tigray

According to local farmers, S. tiliifolia is now the main weed to be removed from croplands in Tigray; it grows rapidly and even suppresses other weed species. On well-managed farmlands, one will generally not observe full-grown S. tiliifolia (Figure 2). The farmers in the study area have experience with manually uprooting S. tiliifolia. While the work in itself is quite easy, because the species is very recognizable and the roots do not resist much (Supplementary Figure S6), it involves additional workload and is a burden, particularly for women and children. However, and depending on time constraints, it is often not weeded out from farm boundaries (Figure 2) and rangeland near farmlands, which will be a source of S. tiliifolia seed in the next cropping season.

Salvia tiliifolia Management on Communal Lands

The conventional strategy has long been the extensive and methodical clearance of invasive plants before they set seed (Engel et al. Reference Engel, Nyssen, Desie, den Ouden, Raats and Hagemann2024; Mack and Foster Reference Mack and Foster2009; Parmesan and Hanley Reference Parmesan and Hanley2015). Whereas it is impossible to totally “get rid of” the invasive plant in this way, it may subdue the growth in that area in the next year, and annual repetitive removal may exhaust the seedbank (Anonymous 2015, 2024). In the study area, experimental community weeding of S. tiliifolia on rangeland showed that 45 person-days ha−1 are necessary for an initial manual S. tiliifolia removal operation (J Nyssen et al. Reference Nyssen, Gebremedhin, Tesfamariam, Haile, González-Gallegos and Ghebreyohannes2024a; Supplementary Figure S7).

Conversely, in communal lands where free grazing is forbidden (exclosures), we observed that S. tiliifolia is totally absent, particularly at locations away from roads (Figure 3). Also, we observed that S. tiliifolia has a stunted growth in shady places with seeds that do not fully mature. Locally, S. tiliifolia coexists with other herbs in peri-urban exclosures, but it does not dominate. In such cases, the grasses and herbs—including S. tiliifolia—are all harvested together (Supplementary Figure S8) to serve as fodder for livestock. In contrast to thistles for instance, withered S. tiliifolia is accepted by farmers as a part of the harvested hay. Establishing exclosures therefore seems the most cost-effective strategy to control S. tiliifolia while sustaining fodder production. In this nature-based approach (Ammondt and Litton Reference Ammondt and Litton2012; Ngondya and Munishi Reference Ngondya and Munishi2022; Tracy et al. Reference Tracy, Renne, Gerrish and Sanderson2004), the recovery of herbaceous and woody vegetation in newly established exclosures would be sped up by S. tiliifolia removal in the first years. Conversely, opening the exclosures for free grazing to relieve the fodder crisis caused by the S. tiliifolia invasion would only result in the exclosures being invaded by S. tiliifolia due to selective grazing. All in all, the mere protection of the indigenous vegetation enables subduing S. tiliifolia at a lower economic cost (Lázaro-Lobo and Ervin Reference Lázaro-Lobo and Ervin2021; Leuzinger and Rewald Reference Leuzinger and Rewald2021; B Nyssen et al. Reference Nyssen, Den Ouden, Bindewald, Brancalion, Kremer, Lapin, Raats, Schatzdorfer, Stanturf, Verheyen and Muys2024).

Figure 3. At Jira, Salvia tiliifolia grows densely along footpaths (A, 13.68472°N, 38.95750°W, 1,991 m a.s.l.), while it is totally absent from the adjacent exclosure (B, 13.67972°N, 38.96028°W, 1,920 m a.s.l.). Both photos taken in October 2024: courtesy of (A) Gebrekidan Mesfin; (B) Miro Jacob.

The ability of S. tiliifolia to dominate rangelands and suppress grasses, particularly in areas of intensive livestock grazing, underscores the urgent need for effective management strategies. Field observations and local knowledge suggest that a combination of weeding on cropland and the establishment of exclosures, where only haymaking but no grazing is allowed, may offer the most sustainable approach to controlling its spread.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Figures S1 to S8 are available as Supplementary Material at https://doi.org/10.1017/inp.2025.14

Data availability

Species observation locations (with photographs) are reported in the iNaturalist database and reported as a reference to Nyssen (Reference Nyssen2024).

Acknowledgments

We thank Kyle Campbell and Mark van Dalsen (iNaturalist) and Raf Aerts (K.U. Leuven) for their help in preliminary identification of the species. Abraha Teklu and the Meserete Birhan ‘Idir traditional neighborhood solidarity group in Hagere Selam are also acknowledged for all assistance. Gebrekidan Mesfin and Miro Jacob (EthioTrees) provided photos and coordinates of areas with dense S. tiliifolia growth. Sofie Annys (Ghent University) assisted in voucher specimen collection and handling. We thank Odile Weber and the Botany team of the Musée National d’Histoire Naturelle du Luxembourg for mounting and housing the voucher specimen.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or the commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.