Introduction

In one of the earliest European accounts of Southeast Asia, Tomé Pires describes in his Suma Oriental early sixteenth century a ‘town in the land of Arqat [an important kingdom in this period in north Sumatra], where a slave market (of men and women) is held in certain months, and [it is] open to all. Anyone who likes can go there in safety; and many people go there to buy slaves’. On the island of Madura, near Java, he claims ‘they have no other merchandise, except rice and foodstuffs, and many slaves.’ Further southeast in the Indonesian Archipelago, he refers to the ‘island of Sangeang’, near Bima, part of the lesser Sunda islands east of Java, which ‘is peopled with many inhabitants [who] go about plundering [and have] many ports and many foodstuffs and many slaves to sell’. In a similar way Pires mentions the Bugis, who ‘have fairs where they dispose of the merchandise they steal and sell the slaves they capture’. On the other side of the Indian Ocean world, Pires described ‘Abyssinia […] on the Red Sea’ that has amongst its main ‘merchandise – gold, ivory, horses, slaves, foodstuffs, etc.’Footnote 1

The travel accounts produced by the ongoing European expansion in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago worlds would continue to describe the widespread slave trade in later centuries. The descriptions of his travels through Portuguese Asia in the 1580s by the Dutchman Jan Huygen van Linschoten explained to his readership in the nascent Dutch Republic that enslaved people from Bengal and Mozambique were traded throughout the Indian Ocean world. Enslaved people from Bengal were, according to Van Linschoten, ‘seen as the most evil slaves and captives of entire India’, while those from Mozambique were seen as the strongest and were ‘made to do the most unpleasant and roughest work’.Footnote 2 From Portuguese ‘firangi’ raiders to Dutch company personnel, Europeans were quick to take up a role in this slave trade. Roughly a century after Van Linschoten, in 1670, the Dutch surgeon Nicolaus de Graaff, who travelled in the service of the Dutch East India Company to the trade office along the Ganges in the northern Indian market city of Chapra, near Patna. He described how ‘people died in masses and lied dead on the roads, in the river, yes, even on the streets and markets.’ He continued to explain that ‘this made the slaves cheap, because pressed by the great hunger, men sell their wives, wives sell their men, parents sell their children, the children their parents, and the brothers and sisters sell each other, for a low price; because for a hand full of rice or two we could buy a male or female slave, and for a rijksdaalder or two one can buy a nice boy or a young women of 10, 12, 16 or 20 years, healthy, but starved from hunger’.Footnote 3

Recent years have witnessed a growing number of studies on slavery and slave trade outside the Atlantic world in the early modern period. Following upon earlier studies that pointed out the significance of slave trade in especially the Western Indian Ocean,Footnote 4 a growing historiography has not only increased the study of slave trade in this region,Footnote 5 but also expanded its scope to other parts of the world Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago world and beyond, ranging from South Africa,Footnote 6 to South and Southeast Asia,Footnote 7 and from the Islamic world,Footnote 8 to Central Asia,Footnote 9 and the Mediterranean.Footnote 10 Several studies have indicated that slave trade was more widespread than previously thought, and have pointed at the pivotal role of expanding European colonialism.Footnote 11 Slave labour gained an important role in both colonial and indigenous production of global commodities such as sugar, silver, pepper and other spices. The expansion of slavery and slave trade in the early modern Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago was linked to the growth of and production for global trade fueled by early modern European colonial expansion.Footnote 12

These insights have challenged older notions of ‘Asian’ slavery that juxtaposed its character to slavery in the Atlantic world. This resulted in characterizations of slavery in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago as being a mainly local phenomenon, according to some scholars even a ‘mild’ form of slavery, concentrated primarily in cities and households, motivated by factors such as status and conspicuous consumption.Footnote 13 In contrast, the recent wave of studies of slavery in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago provide ground for new connections and comparisons. They seem to indicate that the basics of slave trade and commodified forms of slavery in these regions were quite comparable to the Atlantic world. Clearing away the pressing constraints of regionalism, we can now start to question how commodified slavery and slave trade functioned in this ‘Old World’-context from a more global historical perspective. The slave trade itself has been identified as a key indicator, signalling the presence of commodified slavery, and representing existing connections and movements between slave exporting and importing societies.Footnote 14 The regimes of commodified slavery fueled by slave trade in turn functioned alongside, and in interaction with, non-commodified coercion (bondage, corvée) and other labour relations (wage labour).Footnote 15

This renewed interest in slavery and slave trade in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago has led to calls for advancing this field by developing collaborative data initiatives that will allow to close the gap with the Atlantic studies, including the effort to work towards reconstructing slave trade patterns east of the Cape and assessing its impact.Footnote 16 As a way to improve our understanding of slave trade outside the Atlantic world, slave trade prices are fundamental to our understanding of slave trade patterns and markets. For the Atlantic world, a well-developed literature of slavery and slave trade has produced price data for West-Africa,Footnote 17 the Guianas and Caribbean,Footnote 18 the British Caribbean,Footnote 19 MexicoFootnote 20 and the interior of Portuguese Brazil.Footnote 21 This begs the question if we can establish similar prices series for Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago slave trade, and what that can tell us about the slave trade and its role in the early modern world economy?

This article contributes to the renewed explorations of these questions by analysing slave prices derived from evidence from especially the Dutch Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago world. For these parts of the world, the historiography of prices of enslaved people is not very extensive, but the literature nevertheless provides some important starting points. Perhaps most developed is the study of slave trade to and in South Africa. As a result, the Cape of Good Hope is the region for which the most solid price series are currently available, with data collected by Nigel Worden, Anna Jacoba Böeseken and Robert Shell from rural auctions and notarial deeds.Footnote 22 These series indicate a rising trend of the average price of enslaved people, from some 125 guilders on average in the 1670s and 1680s,Footnote 23 to an average of 260 to 270 guilders in the 1720s.Footnote 24 Especially towards the end of the eighteenth century, price levels strongly accelerated, with the average price of enslaved individuals sold in rural auctions peaking over 1,000 guilders in the 1790s.Footnote 25 Beyond the Cape, price data are more fragmentary. A collection of prices is provided by Richard Allen in his overview of European slave trade in the Indian Ocean, but except for the indications valued ‘in kind’, most of these prices cover purchases and sales in British Bencoolen in Sumatra. The overview does not mention the quantity of enslaved or transactions upon which these prices are based, making it more difficult to assess how representative these indications are. The prices strongly vary over time, ranging from 218 guilders in 1706, to an average of 179 guilders for the 1710s, 172 guilders for the 1730s, 156 guilders in the 1740s and 201 guilders in the 1760s.Footnote 26 The prices provided in his overview for the French Mascarenes (Réunion and Mauritius) are much lower, indicating the import (selling) prices of male slaves in 1770–73 averaged around 600 livres, equalling some 138.1 Dutch guilders.Footnote 27 For mid-eighteenth century Portuguese Goa, Jeanette Pinto mentions slave prices ranged between 50 and 75 rupees, which was somewhere between 63 and 94 Dutch guilders.Footnote 28 For the kingdom of Arakan and the Bay of Bengal, Wil O. Dijk collected slave trade prices for early to mid-seventeenth century.Footnote 29 Recent publications have added references to prices of enslaved persons sold in transactions in English and Dutch East India Company settlements in Bengal, in the coastal place of Mahavelona (Foulpointe) in Madagascar, and the rural surroundings (ommelanden) of Batavia in the 1720s and 1730s.Footnote 30

This article contributes to developing a first overview and a better understanding of the development of price levels in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago within the wider global context of early modern slave trade. And although this article significantly expands the body of data on slave prices and slave trade in the Indian Ocean and the Indonesian Archipelago, it is nevertheless important to point out that this field is still in its infancy. This article therefore aims to provide a fruitful ground for new global historical comparisons and a stimulus for future research into slavery and slave trade worldwide. It will not be able to provide the final reconstruction of price levels across the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago worlds, but must be seen as a point of departure. Much more data will be necessary to advance our knowledge of slave trade markets, their development and interactions. More is to be gained from collecting evidence on prices in Dutch and especially non-Dutch sources, and more detail can be gained for the price levels in both slave exporting and importing regions.

The importance of doing this lies in its potential to contribute to several debates. First, the developments in slave trade and prices were often directly related to political, economic and environmental transformations, especially the expansion of colonialism, collapse of polities and natural and human-made catastrophes. Second, slave prices could be more explicitly positioned in explanatory models for slavery, labour coercion and ‘free’ labour. Improving our knowledge of slave prices could enables us, for example, to further explore and test the Nieboer-Domar thesis that the high availability of land and low availability of labour results in labour coercion – the price and availability of coerced labour through slave trade seems a pivotal but relatively understudied factor. Third, improving knowledge of slave prices and trade in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago world allows for more advanced comparisons, between regions within the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago, as well as with the Atlantic world.

Sources and slave trade prices

This article considerably expands the base of available observations for the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago worlds by introducing new price data from a variety of sources and bringing this together with existing data. It draws on new data from several bodies of sources from the Dutch East India Company archives that cover large parts of the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago worlds. This article presents a new data set with 1,739 references to prices in slave trade transactions from a wide range of source material. First, these are references to slave trade and prices collected from digital source repositories, most notably the Generale Missiven (General Letters from the Council of India in Batavia to the Gentlemen Seventeen in the Dutch Republic) and the Dagregisters (Daily Registers) of Batavia.Footnote 31 Second, this data collection includes new evidence on individual transactions from recently created data sets on notarial deeds (acten van transport) and public auctions (venduties). This concerns data on transactions registered in notarial deeds, especially for the city of Batavia (Jakarta, Indonesia),Footnote 32 but also for Makassar, Ambon,Footnote 33 and Cochin (Kochi, India),Footnote 34 and on public auctions in Batavia.Footnote 35 Third, available data from the Overgekomen Brieven Papieren and court records series of the VOC archive,Footnote 36 the data collection of Wil O. Dijk for Arakan and the wider Bay of Bengal region,Footnote 37 and wider existing literature have been used in the analysis of this new source work as much as possible.Footnote 38 Alongside this new slave trade price database, this article uses the database of administration of cargoes on VOC voyages from Batavia (the Boekhouder Generaal Batavia) which contains an important series of registrations of the value of enslaved people transported between different VOC-settlements in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago.Footnote 39

Three important caveats should be mentioned here. First, it is important to realize that this collection of data concerns information from a wide range of different types of sources. This means that it does not always provide a similar type of observation on the slave trade or on the prices in that trade. The valuations of company cargoes, for example, provide a different perspective on the price of slaves than private market transactions. How these relate exactly is an open question. Throughout this article, therefore, evidence will be evaluated and weighed based on the context of a specific observation or source. This makes it possible to bring these different observations together, compare and develop a way to use them to provide an indication for price levels and developments in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago slave trade. Second, since this article aims to compare price developments between different regions, it was considered that this could best be done in current or nominal prices, with all values converted to one single currency (the Dutch guilder) based on their silver or gold content. Certainly, there must have been inflation over time and in different regions, but a conversion to historical real prices for so many different regions and such a long time span is problematic given the lack of data. It can be considered that the dangers of cliometric distortion outweigh the benefits of creating real prices series.

Third, the valuations or ‘prices’ that were placed upon enslaved people were influenced not only by regional variations but were also impacted by variables such age, gender, skill and more. For the Atlantic, we know that male slaves were valued higher than females and children, but these valuation patterns could differ per region and over time. In the Dutch slave trade in West-Africa in the 1720s, female slaves were priced on average at 60% of male slaves. This rose to 70% in the 1730s and 85% in the 1780s.Footnote 40 In Surinam, female slaves were valued on average a quarter less than male slaves.Footnote 41 The differences in valuations of enslaved men, women and children did not only reflect the demand for (certain types of) enslaved people but were also influenced by the demographics of the slave trade, which in turn was also subject to change over time.Footnote 42 The evidence of this article indicates that similar mechanisms were at play in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago, and this means that much more data and study is needed to better comprehend those more refined influence of gender, age and other categories in the formation of prices of enslaved individuals in different parts of the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago in different periods.

The Dutch East India Company, for example, valued the female slaves who were transported by the VOC in Asia on average 16.5% less than the transported male slaves.Footnote 43 Other individual factors, such as the skills and profession of the enslaved, the age or possible disabilities, had an important influence on the price. The Bengalese wigmaker Claas was sold by public auction in Batavia in 1751 for the sum of 200 rijksdaalders, while the male cook Cupido from Malabar was sold for 70 rijksdaalders.Footnote 44 The Buginese Februarij was sold for 150 rijksdaalders and was mentioned to be a ‘bas speelder’, a musician playing the (double) bass.Footnote 45 The slave woman Aurora from Malabar, referred to as ‘oude meijd’ or old maid, was sold for 30 rijksdaalders.Footnote 46 These individual variations are important to take into account, but reach beyond the scope of this article for now. The literature for the Cape of Good Hope suggests that female slaves were on average indeed priced lower, but that enslaved females of fertile age were priced higher.Footnote 47 The result is that the average price of women sold in the notarial deeds of the Cape of Good Hope in the period 1658–1731 was only 3% lower than that of men.Footnote 48 Given these considerations, and due to the availability of data, this article has taken the averages of all available transactions to reconstruct the development of regional price levels in the slave trade.

Patterns of slave trade in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago

The Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago worlds provide a highly interesting case. First, slave trade in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago was multidirectional in the sense that there was a myriad of long-distance middle passages between regions where enslaved people were drawn from and regions where they were transported to. Regions known for slave export could at the same time be importing slaves. Second, slave trade was carried out by a multiplicity of actors. Of course, European companies like the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC), East India Company (EIC) and Compagnie des Indes (CdI) were involved in slave trade directly. And these companies also regulated the slave trade in their domains. Most of the slave trade, however, was carried out by private trade, for example, by non-European merchants, (free)burghers or company personnel. Third, connected to this point, slave trade took place on different levels or scales. We can discern two main patterns of slave trade that existed side by side. On the one hand, there was a trade which we recognize from the Atlantic slave trade with the transport of enslaved humans in large shipments in ships that were refitted or even build especially for the slave trade.Footnote 49 In just a few years’ time between 1659 and 1661, for example, the VOC bought and transported at least 5,000 slaves from the Coromandel coast to Sri Lanka. Mostly forced into slavery as a result of impoverishment and starvation after a major famine in Tanjore, these slave were used to repopulate Dutch Ceylon after a series of conquests. On the other, there was the trade and transport of enslaved people in smaller groups with voyages that were primarily fitted out for other purposes. This trade and transport of enslaved people as a sort of ‘side-business’ was widespread and together these trickling flows must have accumulated to numbers of slave trade that could easily match or even exceed the ‘full’ cargo slave trade. A rough estimate of the ‘permitted’ or ‘tolerated’ private slave trade by crew members of VOC ships indicates that this might have amounted to some 175,000 to 225,000 slaves traded by VOC personnel while engaged on board VOC ships in intra-Asiatic voyages.Footnote 50

Although estimates for the slave trade in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago are generally still very tentative, and presumably still much too low, the current numbers nevertheless indicate something of the importance of slave trade and the existence of commodified slavery. It is estimated, for example, that some 2,000 ‘slaves, captives and fugitives’ were brought from South Asia to Bantam and Aceh every year, providing an estimated total of some 600,000 enslaved persons moved to these polities from the fifteenth to the seventeenth century.Footnote 51 The better studied French slave trade to the Mascarenes is estimated at some 311,383 to 358,215 slaves in the period 1670 to 1848.Footnote 52 For the Western Indian Ocean area, the estimates are most developed, indicating the export to Indian Ocean world destinations of in total some 392,000 slaves from Madagascar, 600,000 slaves from East Africa, and 400,000 slaves from the Red Sea area in the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries.Footnote 53 Other scholars, such as Richard Allen estimate even ‘a minimum of 1,100,000 slave exports from eastern Africa to the Middle East, South Asia, and various parts of the European colonial world’, while Paul Lovejoy estimated that the East Africa slave trade may have amounted to 2,118,000 slaves in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries.Footnote 54 As recently has been remarked, however, we need further research on the receiving areas, and we need to expand our horizon beyond the focus on the Western Indian Ocean, and especially beyond that on East Africa; this is likely to lead to these figures being revised upward.Footnote 55

Recent estimates for the Dutch empire in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago, for example, have set the estimated total of the imports to VOC settlements at a range of 660,000 to 1,135,000 slaves throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth century.Footnote 56 Rough indications on the flows of slave trade suggested that at least some 100,000 to 150,000 slaves were exported from Bali, while at least another 100,000 slaves were exported from Sulawesi. More research is needed to improve estimates, but similar numbers may have been transported to Dutch settlements from the Indian subcontinent, Madagascar and Southeast Africa, as well as the lesser Sunda island region, and the islands and coastal regions of western Sumatra.Footnote 57 Most of this slave trade was private trade. Against the 175,000 to 225,000 slaves transported through private trade by VOC personnel while working on intra-Asiatic voyages, the VOC itself has been estimated to have bought some 37,854 to 53,544 slaves. These numbers are likely to be updated based on further research, but do indicate that much of the rest of this trade was carried out through other private trade by burghers, Asian, Arab or African merchants and high VOC officials fitting out private vessels for slave trade.Footnote 58

The multi-directional long-distance slave trade routes thus connected the different sides of the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago. The ‘Cape Malay’ community in South Africa, for example, traces its origins back to enslaved ancestors brought over from the Indonesian Archipelago. Slaves were transported from different parts of South Asia to the Cape of Good Hope as well.Footnote 59 Early seventeenth century, slaves from the Malabar coast were employed by the VOC to dig canals and build defence works in Batavia (present-day Jakarta, Java). For the Silida mines operated by the VOC in Sumatra, slaves were taken from Malabar and Madagascar, as well as relatively nearby Nias.Footnote 60 For now, it remains largely an open questions how thick these connections between the far ends of the slave trade system of the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago world were, and how these developed over time especially under the impact of European expansion. Most of the largest flows of slave trade were within the different subregions of the large slave trading system of the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago. A large slave trade route was, for example, from Madagascar and Southeast Africa to the northern regions around the Arabian Sea and later to South Africa. This was also the case for the Indonesian Archipelago, where the largest flows of slave trade export were directed from the eastern to the western parts of the archipelago.Footnote 61

This could perhaps lead one to think the forced movements of enslaved people were a mere local or regional affair, but it would be problematic to conceptualize these flows of slave trade as ‘local’ or ‘regional’ as opposed to intercontinental trade. The distance between Maputo (Mozambique) and Aden (Yemen), for example, is some 4,500 km. It is around 3,000 km from Tolanaro (Madagascar) to Cape Town (South Africa). In comparison, the distance from Elmina (Ghana) to Pernambuco (Brazil) is around 4,000 km, while it is around 5,300 km from Benguela (Angola). It is some 6,000 km from Elmina (Ghana) to Paramaribo (Surinam). Distances within the Indonesian Archipelago were shorter. From Nias to Jakarta is some 1,400 km, while it is some 2,800 km from the western parts of Papua. In turn, it is 3,800 km from Kolkata (India) to Jakarta (Indonesia). And slaves that were, for example, brought from Madagascar via the Cape of Good Hope to the Silida mines on Sumatra were transported over at least 12,000 km geographical distance. Of course, all of the travel distances depended upon sailing routes, and the travel time depended upon weather conditions.

Valuations of a global Company

So let us explore what we can learn about the development of prices of enslaved people in the multi-directional trade of the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago world. This study distinguishes two types of observations: first, the valuations by the VOC of the slaves it owned and transported, and, second, prices of enslaved groups or individuals in market transactions. The VOC valuations provide long-term observations on the development of price levels for a number of important slave trade regions, but need to be checked against other indications from sources on private slave trade. This collection of evidence for market transactions provides clusters of price data for specific places in shorter moments of time, but can provide in-depth insights in the development of market level slave prices, their relation to VOC valuations and the question whether these need to be corrected or not. We will thus first turn to the data with VOC valuations, and then to the data with market prices.

Although the VOC itself was not the largest slave trader, its extensive data does provide historians with unique information on the valuation of slaves in different regions. In its administration called the Boekhouder-Generaal Batavia (Bookkeeper General Batavia), the VOC registered the cargoes of its voyages, mentioning the volume of the products, their value, the origin and destinations. Unfortunately, this administration is preserved for roughly half of the years of the eighteenth century and provides long-term insights. The values in the BGB generally reflect the ‘purchasing’ or ‘cost’ price in the region where commodities (and in this case enslaved people) were acquired.Footnote 62 Of the 9,534 slaves registered in the BGB, a total of 249 slaves (shipped in 32 voyages) have not been administrated with a value, leaving price indications for a total of 9,285 slaves shipped in 408 voyages. These VOC shipments thus provide important indications for the price levels of slaves for different regions across the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago world.Footnote 63

The departure and arrival regions of the VOC slave transported covered by the BGB administration include important parts of slave trade patterns across Asia, but not all. The data set, for example, does not include any voyages from Bali and very little from Nias, as these routes were dominated by private slave traders, especially Balinese, Chinese and VOC-burghers. Most of the slaves in this VOC-administration were transported from Makassar (3,004), followed closely by Timor (2,098) and Malabar (1,553). The main destination for the slaves transported from these three regions was Batavia – reflecting in this case not only the importance of Batavia as a slave importing region but also the Batavia-centred nature of the administration. In the case of Macassar, almost all slaves were transported directly to Batavia (2,956); this was a bit less for Timor (1,534) and Malabar (930). The second most important destination for slaves from Timor was Banda (564), for Malabar this was Ceylon (614). Batavia was further supplied by slaves from Sumatra’s west coast (519), Ceylon (431), Ternaten (385), Coromandel (99) and various other settlements (63). In return, slaves were shipped further (or exported) from Batavia mainly to Ceylon (698), Malacca (125), Sumatra’s west-coast (121), Bantam (116), Timor (71), Palembang (45) and various other settlements (56).

In this way, the values mentioned in the BGB do provide indications for the long-term development of prices in slaves in an important selection of regions across Asia. As for other cargoes listed in the BGB, the valuations listed for transported slave generally reflect purchasing or minimum values for the regions from where the VOC voyages departed. This provides unique indications for slave exporting regions especially, mainly Makassar, Timor and the Malabar coast, and due to lower numbers more tentative also for Sumatra’s west coast and the Coromandel coast. The BGB registered not only a high number of arriving slave voyages for Batavia but also numerous voyages that departed. For Batavia, it must be reminded, however, that this city and its ommelanden were the most important slave importing region, and this may have impacted the gap between the VOC slave valuations and local market prices.

Two important exceptions should be mentioned to the general rule that the VOC values in the BGB generally applied directly to the regions from where VOC voyages departed. Voyages from Ceylon often carried cargoes and enslaved people from other parts of South Asia, especially the Malabar and Coromandel coasts. In May 1703, for example, the ship Ter Eem arrived from Colombo with 26 slaves, referred to as ‘Malabars’. The ship Ter Eem arrived in Colombo on an outward bound voyage from Amsterdam, and the slaves may have been taken from Malabar to Colombo by another VOC vessel.Footnote 64 On other occasions, ships that transported slaves came directly from Malabar and continued from Ceylon to Batavia. The ship Huis te Nieuwburg, for example, arrived in Colombo in April 1702 with 27 ‘male’ slaves, and continued with the same 27 slaves to Batavia in June 1702. The slaves were now referred to as ‘male Malabars’ (mannelijke Malabars). Both legs of the voyage were registered as separate voyages, but the slaves were in both instances valued at 1,036 Indian or ‘light’ guilders, 3 stuivers and 8 penningen.Footnote 65 Due to its role as transit hub in the slave transports from especially the Malabar coast to Batavia, in the case of Ceylon the administered slave values seem less indicative for the region itself, and more for the regions of origin, in this case the Malabar coast. This explains why the available BGB indications on Ceylon slave values are almost similar to those of the Malabar coast (for the periods 1710–20; 1740–60 – see Table 1), despite the fact that the VOC settlements on Ceylon were slave importing regions, and the Malabar coast an export region. Not entirely dissimilar were the dynamics of valuations for slaves transported from Ternate. More than half of the slaves transported from Ternate were marked as ‘gift’ (geschenk).Footnote 66 Slaves were gifted by local rulers to the Dutch East India Company to maintain relations, as a sign of tribute. On April 30, 1763, for example, the ship Vrouwe Elisabeth Dorothea departed from Ternate to Batavia with 5 slaves, 51 ‘paradijsvogels’ or birds of paradise (apus), and 92 turtle horns from ‘the king of Gorontalo and Salwatty’.Footnote 67 Later that year, on the 2nd of August, the ship Zeelelie set sail from Ternate to Batavia with 22 slaves that were gifted by ‘various rulers’.Footnote 68 These slaves were not necessarily local subjects from the polities of these rulers; in contrast, it seems the gifted slaves were not from Ternate, but from nearby enslavement regions, especially Papua. On the ship Hamer setting sail from Ternate to Batavia in August 1712, for example, the nine slaves gifted ‘by the kings of Ternate and Tidore to the Honourable Company’ were referred to as ‘male Papuans’.Footnote 69 The same was the case a year later for the 10 slaves transported on the ship Peter and Paul for the slaves gifted by the rulers of Ternate, Tidore and Bacan.Footnote 70 These practices of tributary slave gifting to the VOC continued far into the eighteenth century, but the references to the ‘Papuan’ origins of gifted slaves are most explicit in the early eighteenth century, since for Ternate the references to origins of slaves faded in later years.Footnote 71 Since for Ternate the gifted slaves were the majority, the practice of gifting slaves imported from other enslavement regions makes these valuations less indicative for Ternate and more indicative for the regions where gifted slaves were extracted from, in this case especially Papua.

Table 1. VOC valuations (BGB) of slaves in Malabar, Ceylon and Coromandel (guilders)

All slave prices are noted in weighed averages per decade.

Table 2. Market prices (Acten van Transport) and VOC valuations (BGB) of slaves in Batavia (guilders)

Slave prices are noted in yearly averages for the Acten van Transport (with the total number of slaves) and weighed five yearly averages for the Boekhouder Generaal Batavia (with the total number of slaves, and the number of references or voyages involved).

Table 3. Market prices (Acten van Transport) and VOC valuations (BGB) of slaves in Makassar (guilders)

All slave prices are noted in weighed averages per decade.

In smaller numbers, gifted slaves were also transported from Makassar (88) and Timor (21). For Makassar and Timor, it is likely that the gifted slaves came from the Sulawesi and Timor region themselves. On Sulawesi local wars and village robberies created a steady stream of enslavement that may very well have where the slaves gifted by the rulers of Gowa and Boni may have come from. In the region of Timor and nearby islands, people were also enslaved in the conflicts between the numerous local polities, or could be claimed by rulers from populations considered slaves, as the example of the memoires of the slave Wange on Flores indicates.Footnote 72 Although these gifted people, often men, could be expected to have been amongst the more prestigious and expensive slaves, for neither of the three regions the valuations of gifted slaves differed significantly from the average slave valuations. In contrast to Ternate, gifted slaves were only a small minority amongst the total number of transported slaves in the case of Makassar and Timor (less than 3% and 1%). In this case, the BGB data thus seem to provide indications for these regions specifically.

Taking into account this contextualization of the valuations for different VOC regions, the questions remains, however, how these long-term indications of slave valuations relate to general market prices. The VOC did not claim a monopoly in the trade of slaves; its slave trade accounted for only a half per cent of the total value of the VOC-trade in the eighteenth century.Footnote 73 The slaves mentioned in this administration were not always bought directly prior to the specific transportation on a VOC ship, but could for example be in possession of the VOC for already a longer period of time and only moved between settlements for internal purposes. On the third of June, 1780, for example, the ship Kleine Pallas set sail from Batavia to Palembang with ten slaves ‘from the artisans quarter’ – the public works of Batavia where slaves and convicts were employed for work related to the city’s infrastructure. In these cases, the valuations thus do not seem to represent the actual expenses of buying these slaves, but a (fictive) purchasing value, or a basic indication of what it would cost to replace a slave in the region from where he or she was transported or originated from. The VOC functioned as a Company State. Not only could it easily hire slaves from its personnel and citizens, it also used the labour of convicts and slaves that were deemed ‘unmanageable’ by private owners. The VOC put up various regulations (registration of sales of slaves, (temporary) bans on the trade of specific groups of slaves to specific regions) and it imposed taxes on slave transports. This position of the VOC as a large merchant and government operating throughout Asia, of course, may have affected its position in slave markets, which in turn poses the question whether these VOC (purchasing) value indications were significantly lower than average market prices? And if so, what the difference between average market prices and the prices of VOC was?

Prices in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago slave trade

In order to answer these questions, we need insights into wider market prices in the trade in enslaved people and in the regional differences and developments across the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago. As explained in the introduction, this article can draw upon a collection of data, including a total of 1,739 references to prices in slave trade transactions, involving in total 13,630 enslaved persons.Footnote 74 This collection concerns mostly private trade, but includes 54 references to transactions in which the VOC is the buyer (of in total 4,955 slaves) and that are not in included in the BGB. This allows to compare the valuations of slaves by the VOC in the Bookkeeper General of Batavia administration with indications of price levels in slave markets. This collection of data has been compiled from information preserved and collected in different key series of the VOC archives. The data set thus covers some parts of the VOC world more extensively than others. This means that comparisons can be constructed in more detail for those specific regions and moments for which sufficient data are available.

Slave trade and prices in Batavia and ommelanden

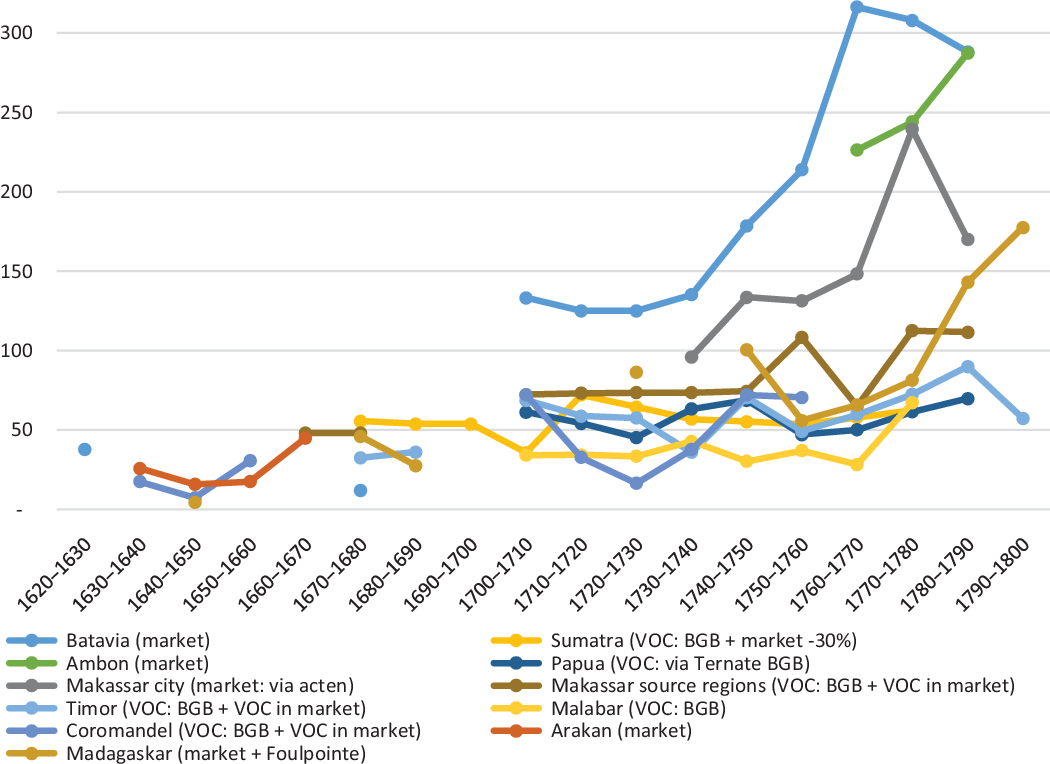

Not surprisingly, most detailed comparisons can be made for the region of Batavia and its surroundings. The prices mentioned in the acten van transport, the notarial deeds of slave transactions, provide the most precise indication of market prices in and around the city of Batavia. The averages of the cross-section years provide a clear rising price trend over the eighteenth century, with yearly averages increasing from 133.2 Dutch guilders in 1700 (N = 273), to 212.2 guilders in 1751 (253); 289.8 guilders in 1770 (89) and 288.2 guilders in 1780 (216). For the middle of the eighteenth century, estate auction prices are available alongside the prices in the private transactions registered with notaries. These auction sells were on average a bit more than 10% lower than the market price levels in Batavia. If we use averages in which every reference has the same weight, slaves in auctions were on priced at 174.7 guilders in 1747 against 197.4 guilders in regular transactions and 182.5 guilders against 212.2 guilders in 1751. In these auctions, however, included more instances of groups of enslaved that were sold together and were priced higher because of specific skills or social roles. In 1751, for example, a group of eight slaves was sold for the exceptionally high price of 1,134.3 Dutch guilders per person.Footnote 75 If we take the weighted averages of these auctions, the prices are thus closer to market prices (as is visible in Figure 1).Footnote 76

Figure 1. Slave prices in Batavia, 1620–1790 (guilders).

The price averages collected for these cross-section years are slightly higher than the indications available in the study by Bondan Kanumoyoso based on the same notarial records for the ommelanden of Batavia in the 1720s and 1730s.Footnote 77 His study indicates that Balinese slaves were usually priced the highest, with average prices ranging between 140 and 160 Dutch guilders.Footnote 78 Slaves from Sulawesi and Sumbawa were on average sold for 120 to 140 Dutch guilders (150 to 175 Indian guilders), while slaves from other places in the Indonesian archipelago were sometimes bought for less than 120 Dutch guilders (150 Indian guilders). Kanumoyoso reminds us rightfully that the variation of prices was high: the most expensive slave was sold 280 Dutch guilders, while the lowest priced was sold for 40 guilders. As the cross-section years for the data presented in this article stretches over a longer period of time, the variation of prices was also higher, with one female slave from Tringamo sold for a price as high as 1,800 guilders in 1780, and three female slaves (from Bali and Bengal) sold for 52.8 guilders in 1700.Footnote 79

Two important factors might explain the small difference in prices for the cross-section years (1700, 1751, 1770 and 1780) and the sample for the ommelanden in the 1720s and 1730s. First, the prices vary for different categories of slaves, as well as for different categories of slave sellers and buyers. In addition to different valuations for slaves from different regions, distinctions were made according to gender, skill and even appearance. An important factor were also the differences for categories (or ethnicities) of slave buyers and sellers, with Europeans generally paying (or having to pay) a higher price. Second, there was an important difference between the city of Batavia and its urban and rural surroundings (the ommelanden). This is a rough distinction because contemporaries made distinction between the ‘inner city’ (the European dominated city within the city walls), the neighbourhoods in the ‘outer city’ (the urban areas outside the city walls), and different parts of the ‘ommelanden’ (the rural production areas around the city). A precise distinction between the outer city and the ommelanden is difficult to make here, however, since the urban areas of Batavia flowed naturally into the also densely inhabited rural environments. And the main distinction made in notarial deeds for place of residence was between ‘within’ or ‘outside’ the city walls. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the price levels between the inner city of Batavia and outside areas seem to have been roughly similar – with slaves priced in 1700 on average 131.6 guilders for slave sellers recorded as living in the inner city (N = 56), against 133.2 guilders for slave sellers living in the outer city (67). Later in the eighteenth century, however, slave prices tended to be higher for slave sellers from the inner city than those from the outer city. With the demand for slave labour slowly lessening over the eighteenth century, the difference grew from an average in 1751 of 241.5 guilders for the inner city (22) against 185.6 guilders for the outer city (95), to an average of 351 guilders for the inner city (17) against 266.4 guilders for the outer city (100). It must be noted that the number for 1770 shows the reverse picture, but this seems distorted due to a too low number of slave sellers in the inner city (only 6). The overrepresentation of Chinese and free Christian women amongst the inner city slave sellers may have been a factor. The difference between inner and outer city price levels could thus also be connected to the different backgrounds of slave buyers and sellers in these parts of Batavia.

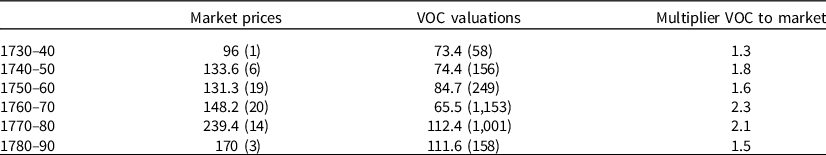

Based on the indications of the price levels in slave trade transactions, it is possible to compare these market prices in and around Batavia with the valuations of slaves transported from Batavia by the VOC in the BGB administration. This comparison indicates that the VOC valuations for slaves transported from Batavia were much lower than the market prices paid in and around Batavia. This gap also grew over time (see Table 2), from a factor 1.3 to 2 in the first half of the eighteenth century to a factor 2.4 in the second half of the eighteenth century (and a peak of a factor of 3 mid-eighteenth century). It must be remembered, however, that Batavia was one of the largest slave importing regions in the VOC empire, together with regions such as the Cape of Good Hope, Silida and the Banda islands. As demand could push market prices up, it seems that the gap between the conservative VOC ‘purchasing’ or ‘cost’ valuations and the price in private slave trade transactions was higher in importing regions than in exporting regions.

Using VOC valuations for other regions – comparing market prices for Sulawesi and Malabar

Similar comparisons should thus be made separately for the different regions involved in the slave trade. The case of Batavia indicates that it is more difficult to rely on BGB indications for importing regions, and that these valuations are perhaps better indicators for (purchasing) price levels in regions where slaves were exported from. Applying these indications for export regions is, however, less straight forward than it might seem, especially given the multidirectional character of the slave trade in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago. This could mean that regions sometimes did not have a simple ‘export’ or ‘import’ role, but could be marked by a combination of the two. At least two types of regions should be discussed in that respect. First, there were export hubs that channelled the slave exports from other regions. This was perhaps most clearly the case for the port city of Makassar. As one of the major ports in the slave export from the island of Sulawesi and surrounding regions, it has been estimated that in the eighteenth century yearly no less than 3,000 slaves were exported to Batavia.Footnote 83 Already before the conquest of the city by the VOC in the second half of the seventeenth century, Makassar sourced slaves across the region, from Manggarai, Timor, Tanimbar, Alor, Butung, Mindanao to Brunei. The Dutch conquest channelled the slave trade to VOC regions through Makassar and provided an important incentive on slave raiding in the region. The city of Makassar was thus a hub for slave export from a wide regional network, while as a city it was at the same time also a destination for slave trade itself.Footnote 84 This seems to have created a ‘double character’ in which VOC valuations may have reflected in part the trends of export prices of the surrounding slaving source regions, while the urban Makassar (market) prices may have reflected also local urban demand.

Slaves were thus transported in large shipments (see Table 3) from Makassar by the VOC directly, or by local Asian merchants and high VOC officials who participated actively in the slave export. Slaves were also traded in Makassar and exported through the private trade activities of lower VOC personnel, burghers or Asian merchants transporting slaves as a side business while travelling between Makassar and Batavia. Evidence of the latter flow can be found in the Batavian notarial archives through references of the transaction history of a slave sold in Batavia. In some cases, proof of earlier transactions were added to the documentation, and this was especially the case for prior transactions in Makassar, providing a total of 62 references to market prices in urban private trade. These can be compared to the BGB administration.Footnote 85 This shows indeed that market prices were significantly higher than VOC valuations, in this case a factor 1.3 to 1.8 in the period 1730 to 1760, and a factor 2.1 to 2.3 in the following decades up to 1780. After this period, it seems the gap between market prices and VOC valuations shrank along with the declining slave prices (to a factor 1.5). The double character of Makassar as a larger urban centre and an important transit hub for the regional export slave trade seems to have resulted in VOC (BGB) price valuations providing a better indication for regional export prices, while the indications of prices in private transactions reflected more closely the price levels in the local urban market.

The second type that needs further examination here consists of regions that underwent significant change in their position or role in slave trade networks over time (see Figure 2). The Malabar region, and the city of Cochin especially, was one of the important regions for slave exports in both the VOC and wider Indian Ocean worlds. The BGB data provide a good indication of the long-term trend, while market prices can be derived from a series of local acten van transport. Unfortunately, in Cochin prices were less frequently registered than in Batavia, possibly because the acten were drawn up by the local secretary of the Council of Police instead of notaries. Only fourteen indications of prices in the local acten have been retrieved from the thousands of transactions. Another three indications have been found in the OBP series. These transactions involved in total 58 enslaved persons for the entire eighteenth century. A reference for four slaves sold in 1706 has not been used here, because these were sold as a family for an exceptional high price.Footnote 86 Since there was only one price reference after 1770, this transaction has been left out as well.Footnote 87 This provides us with the comparison between VOC valuations and market prices as shown in Table 4 below. Interestingly, the VOC valuations seem quite on par with market prices in the first half of the eighteenth century. In the second half of the eighteenth century, market prices are higher and the gap with VOC valuations increased.

Figure 2. Slave prices in Makassar and Timor, 1660–1790 (guilders).

Table 4. Market prices (Acten van Transport) and VOC valuations (BGB) of slaves in Cochin (guilders)

All slave prices are noted in weighed averages per decade.

This sudden turn around the middle of the eighteenth century seems to be reflecting the changing position of the VOC on the Malabar coast. Until the early 1740s, the VOC had enjoyed a relatively influential position, binding several local kingdoms through contracts and claiming sovereignty over local Christian communities beyond its own borders. This position severely weakened after the VOC lost wars to the expanding kingdom of Travancore and signed a treaty that imposed a regional non-interference policy on the Company in 1753.Footnote 88 This may have forced VOC settlements such as Cochin into a less central role in the slave trade exports, leading to rising prices in urban private transactions. In contrast to the low prices of the first half of the eighteenth century, the resulting higher market prices after the turn of the middle of the eighteenth century now compared more with slave importing regions along the Malabar coast. For the large slave-owning metropole Goa, for example, mid-eighteenth century prices have been mentioned varying from 94.1 Dutch guilders for a male slave to 62.7 Dutch guilders for a young slave girl.Footnote 89 The shift in prices on the Dutch Malabar coast may thus have signaled the shift from an export dominated region in which both private and VOC buyers could relatively easily source slaves along the coast and in hinterlands. A new situation occurred in which the supply of slaves to the urban market of Cochin was now less undisturbed, resulting in higher market prices more conform to other urban centers such as Goa, while the VOC continued to value its slave transports according to lower regional export slave price levels.

If this assessment of the relation between slave trade export, (urban) markets and VOC valuations is correct, this implies that VOC valuations indeed closely resembled regional export prices. In regions that were mainly dominated by export slave trade and where slave imports and large demand from urban markets played a less significant role, this would mean that VOC valuations provide a relatively direct indication of purchasing or cost prices for the trade of large groups of enslaved human beings. For these instances, there is thus no need to multiply the VOC indications, except if one wants to come to an assessment of higher price levels in specific urban centres or other places of high demand for these regions. Of course, similar to the Makassar and Cochin examples, some regions were characterized by a combination of overall regional slave trade export alongside slave import to local hubs or zones with high demand for slave labour. This was the case, for example, for the island of Sumatra where some areas were important in enslavement and export slave trade, while simultaneously in specific areas large numbers of slaves where imported from long-distance slave trade for the labour in mines and pepper production. Again, VOC valuations seem to provide a good indication of price levels for the slave export from the region; the wider collection of prices shows a larger variation indicating both the higher levels of slave importing areas and export slave trade. Other regions, such as Timor or the Coromandel coast, however, were more clearly only slave exporting regions.

Reconstructing Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago slave trade price levels – a first attempt

Thus, in sum, the VOC (BGB) series can provide long-term price indications for the slave export from the areas of Timor, Papua (via Ternate), Coromandel, Malabar, Sumatra and the Makassar slave sourcing regions around the Flores Sea, Gulf of Boni and Makassar Straits. Additional references to prices are available for the mid-seventeenth century large scale slave trade by the VOC, especially for the regions in the Bay of Bengal, Makassar and Timor, reflecting early export slave price trends in these regions.Footnote 90 Market prices in turn are better indications for the higher price levels of slave importing regions, especially local urban demand in Batavia, Ambon, Makassar and Cochin.

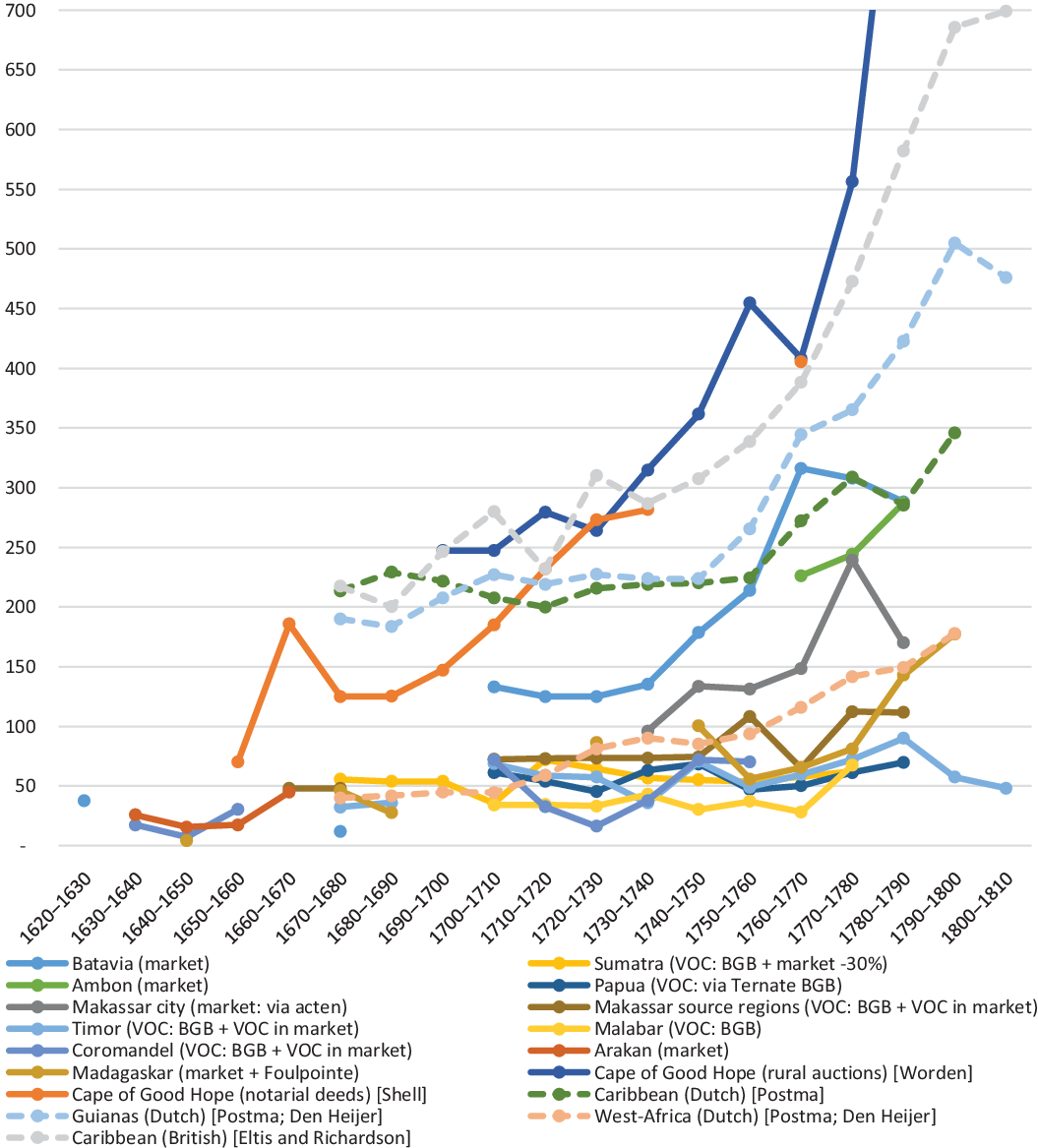

Taking together the evidence from VOC and market prices, it becomes clear that the price of slaves differed strongly per region, with marked differences between regions that were overall ‘supplying’ or ‘demanding’ slaves. Prices were highest in regions such as Batavia, Macassar and Ambon (see Figure 3). These were important destinations for the slave trade, both as centres of economic production (Batavia, Ambon) and places of transit (Batavia, Macassar). Regions that were important suppliers for the slave trade were characterised by much lower price levels. The prices of supplying regions in Southeast Asia – in this case Timor, Papua (via Ternaten as transit hub) and Sumatra’s west-coast – were below the levels of destination regions. Price levels in South Asian slave exporting regions were structurally a bit lower than in Southeast Asian supplying regions. This is interesting as these regions in South Asia seemed to have been supplying slaves to different parts of the Indian Ocean and Indonesian archipelago worlds (e.g. Java and the Cape of Good Hope), but were sometimes important destinations for slave trade as well (e.g. Malabar). In the course of the eighteenth century, slave prices seemed to have risen more strongly in importing regions than in Southeast and South Asian exporting regions. The price gap between supplying and demanding regions widened especially in the Indonesian archipelago in the second half of the eighteenth century.

Figure 3. Slave price levels in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian archipelago (guilders) – combined and corrected data.

Global comparisons

These insights into the price levels in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago worlds can be compared to regions where price series were already available, especially South-Africa, West-Africa and the America’s. Since the prices for the different parts in Asia are already converted to their values in Dutch (or heavy) guilders, these can be compared directly to price series for South Africa and the Dutch Atlantic. The data for the British Caribbean can be converted based on the silver content of the British pound.Footnote 91

The Cape of Good Hope (South Africa)

The price data available in the literature for the Cape of Good Hope are derived from notarial deeds and rural auctions.Footnote 92 The slave prices based on the auction records of estates of Cape farmers entail the total enslaved population of each farm, with auction prices reflecting ‘the market value of each slave related to the demands of the locality and time’ (see Figure 4).Footnote 93 The notarial deeds contain individual transactions of slaves similar to the data collected for Batavia. This collection contains more observations on the slave trade in Cape Town. The price series for these notarial deeds is also based on the average of all transactions (and is little different from the average of all the transactions of male slaves).Footnote 94 The rural auction price series are periodic averages (developed by Worden); the notarial deeds series are yearly averages. The slight differences between the two price series might be explained by the more urban context of the notarial deeds, including more transactions of enslaved individuals recently imported from overseas, resulting in slightly lower prices.

Figure 4. Slave prices at the Cape of Good Hope, rural auctions and notarial deeds compared (guilders).

The Atlantic

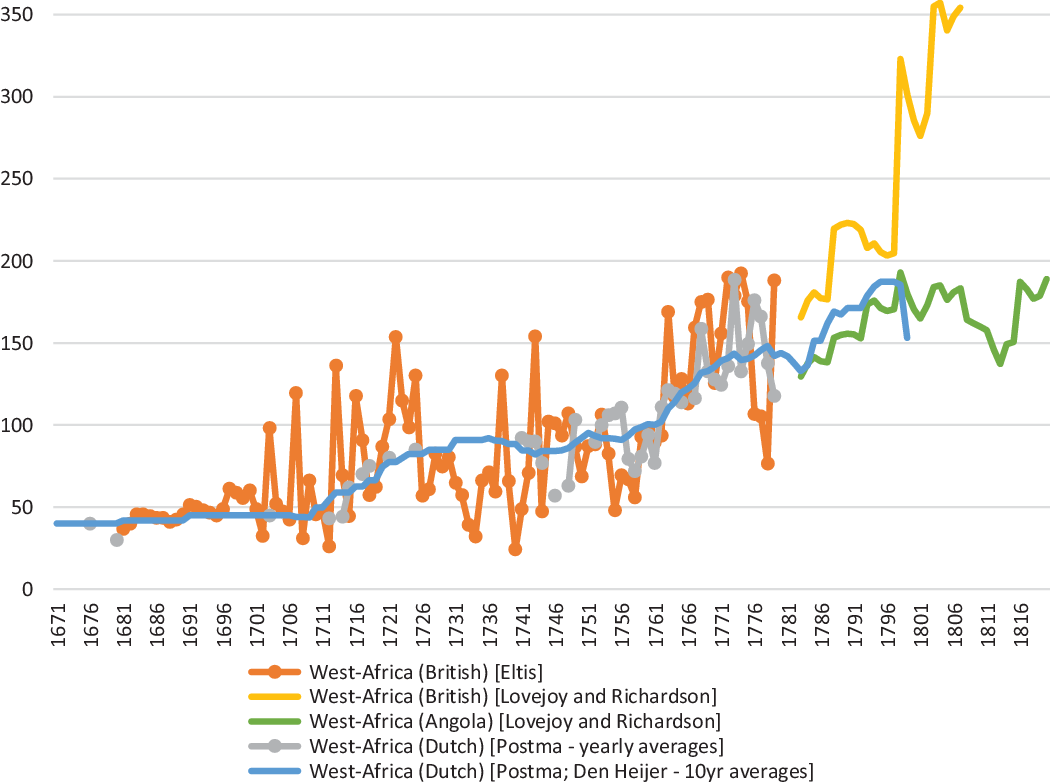

The rich literature of the Atlantic slave trade provides advanced price data for different regions in West-Africa and the Americas. As Patrick Manning emphasized, ‘the process of enslavement resulted in a two-tiered price structure, distinguishing the very low price of a newly taken captive (a price not based on the value of the person but on the cost of capturing him or her), and the higher price of a slave ready to be put to work (a price based on the value of that slave’s potential output)’.Footnote 95 The strict divide between slave export regions in West-Africa and slave import regions in the Americas may have increased the price differences. In West-Africa, slave trade was conducted through the exchange of import goods such as textiles, iron bars, beads, cowrie shell, silver coins and more.Footnote 96 The prices of the slave trade in West-Africa are thus based on the values of the cargoes that were used to buy enslaved Africans. This has resulted in several price series. Given the small numbers and the nature of the trade along the coast, it is often difficult to make distinctions between different buying regions. The price series that are available can best be described as series for the slave trade by British, Dutch and Portuguese merchants – with the later focussed on the regions of Luanda and Benguela in Angola (Figure 5).Footnote 97 More price data are available for the American import regions. In the America’s, enslaved Africans were sold either based on contracts or via public auctions. The prices between these methods of trade and payment could differ, but do not complicate the reconstruction of price levels.Footnote 98 Price series are available for again British and Dutch trade, and for two important early modern disembarkation regions, the Caribbean and the Guyanas (see Figure 6).Footnote 99

Figure 5. Slave prices in West-Africa, 1671–1820 (guilders).

Figure 6. Slave prices in the Guyanas and Caribbean, 1671–1820 (guilders).

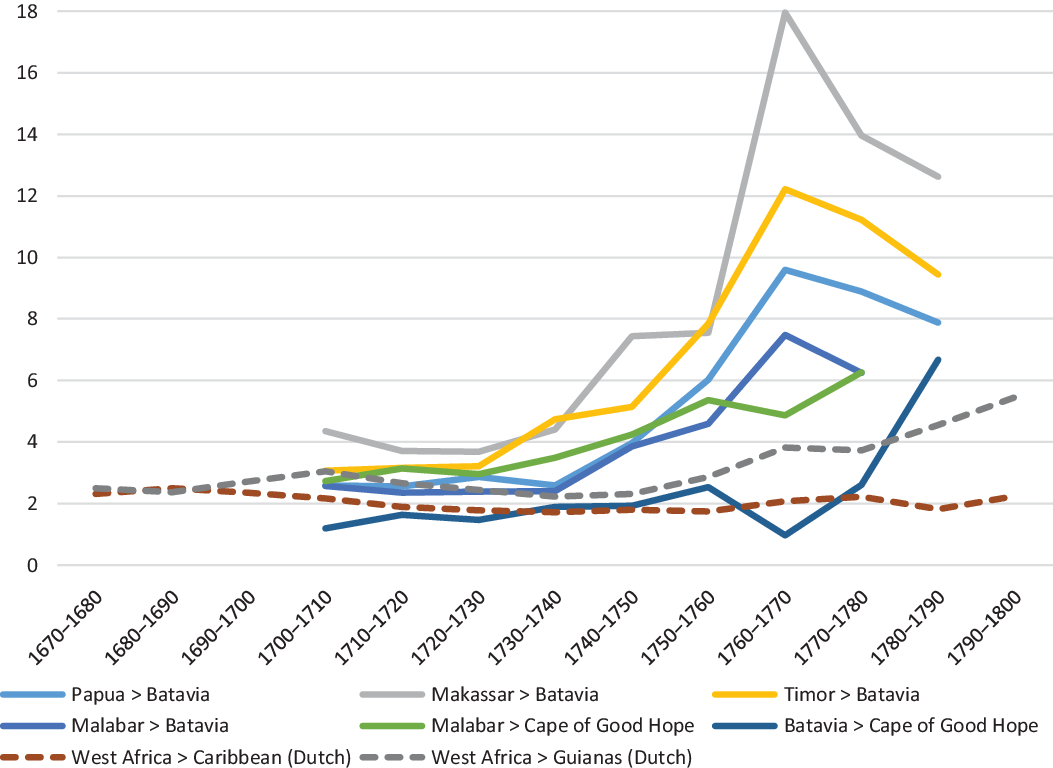

Exploring price levels in the Atlantic, Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago

Based on these series, the development of price levels in the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago in the seventeenth and eighteenth century can be compared. Figure 7 contains price series for those regions in the Indian Ocean, Indonesian Archipelago and Atlantic worlds for which sufficient data is available. A clear distinction arises between sourcing and importing regions. This means that for the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago regions, the market or VOC valuations could be used, mostly uncorrected. Only in the case of the west-coast of Sumatra, the market values needed to corrected to reflect purchasing or export prices. The picture that emerges from this overview provides some remarkable insights.

Figure 7. Slave prices in the Indian Ocean, Indonesian Archipelago and Atlantic worlds compared, 1620–1810 (guilders).

A first striking conclusion from the comparison of price levels in the slave trade worldwide is that the eighteenth century the price of enslaved people rose strongly in slave importing regions across the globe. For the Atlantic, we know that the demand for slave labour rose in the Americas as well as in parts of West-Africa.Footnote 100 Except for some regions in the western Indian Ocean, such as Madagascar, East Africa and the Cape of Good Hope, the slave trade of the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago was not directly connected to the Atlantic system. The rising price levels thus seem to indicate a rise in the demand for slave labour that was not limited to the Atlantic, but also took place in slave importing regions in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago. In the available data within the scope of this study, this most clear for Batavia, Makassar and the Cape of Good Hope. The rise in the price of slaves in the Cape was perhaps most pronounced. This is interesting as the Cape was for most of this period involved in the Asian trading system, importing slaves from East Africa, Madagascar, South and Southeast Asia. Only very late in the eighteenth century, the Cape became linked up to the Atlantic slave trade, but even then mainly through the export of slaves from the African east-coast and Madagascar to the Atlantic.Footnote 101 The rising trends in prices in Indonesian Archipelago regions stagnated towards the end of the eighteenth century. Especially the rising prices in Batavia and its ommelanden were curbed in the 1770s, possibly indicating the stagnation of slavery-based production regimes already before the age of abolitions. This did not mean the end of coerced labour as the eighteenth century witnessed the expansion of the direct and indirect use of coercive corvée labour regimes by the VOC to increase the production of global commodities such as cinnamon, indigo and especially coffee. After the strong expansion of the use of slave labour in the VOC world in the seventeenth and eighteenth century, the role of slave labour thus seems to have reduced as the colonial economy transitioned to corvée and contract labour for agricultural production on Java and in the Batavian ommelanden towards the end of the eighteenth century.Footnote 102 This marks a stark contrast to Atlantic regions in which slave labour continued as the main force of (colonial) production even after the abolition of slave trade.

Second, most but not all regional price levels in South and Southeast Asia remained below the price levels of the American regions, which could be supplied ónly through long-distance slave trade. Only those Asian and African regions that where primarily slave importing regions and where slave labour was in high demand, most notably the Cape of Good Hope and Batavia, were marked by price levels that approached or even exceeded Atlantic levels. This did not mean, however, that slavery and slave trade mattered less in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago. These differences either between oceanic regions or within these different parts of the world cannot be explained by perceived regional characteristics of ‘Asian’ or ‘Atlantic’ slavery.Footnote 103 The slave trade was part of commodified systems of slavery that had much in common. We have to look therefore at the dynamics of the slave trade itself and its impact on the development of prices in the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago. Noticeable aspects that must have played an important role were that of the direction of trade and of the distances between supplying and demanding regions. The Guyana’s and the Caribbean were largely supplied through a single very long-distance Atlantic middle passage. Almost all demanding regions in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago, including the Cape of Good Hope and Batavia and the ommelanden, could instead draw slaves from both long distances (South Asia) and much shorter inter-regional slave trade trades (Makassar; Bali; Timor). This multiplicity of slave trade sourcing regions might explain why prices in exporting regions of the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago worlds responded differently to the growing demand and rising prices in importing regions.

Third, price levels in exporting regions in both West-Africa and South and Southeast Asia did not keep up with the rising price trends. Price levels in slave exporting regions around the globe were generally low and quite comparable. In the 1670s, the cost of buying an enslaved person was on average 32 Dutch guilders in Timor, 40 in West Africa, 46 in Madagaskar, 48 in Makassar. In the 1740s, prices in export regions were on average 85 Dutch guilders in West Africa, 74 in Makassar, 69 in Papua and 30 in Malabar. The slave trade made the lives of enslaved non-Europeans relatively cheap. In comparison, the average earnings of a sailor in the service of the Dutch East India Company late seventeenth century were around 10 Dutch guilders per month. Across the globe, the price of an enslaved person was thus well below this yearly salary of 120 Dutch guilders. Different parts of the world nevertheless showed nuanced differences in developments of slave prices in export regions. Late seventeenth century, prices in West Africa were roughly similar to export regions in South and Southeast Asia (Malabar; Arakan; Bengal; Makassar). Prices started to diverge strongly, however, over the course of the eighteenth century, with prices in Malabar, Coromandel and Papua remaining lower, prices in the Makassar slave sourcing regions (and to lesser extent Timor) rising slightly, and prices in West Africa rising the most especially in the second half of the eighteenth century. This corresponds with the indications for demanding regions that – with the exception of South Africa – the prices in the Asian slave trade system did rise, but more slowly than the more rapidly rising prices of the strongly expanding eighteenth century Atlantic system.

Fourth, one last interesting feature of slave trade routes between Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago regions must be noted in comparison to the Atlantic middle passage. The margins between price levels in supplying and demanding regions in absolute sense were much higher in the Atlantic world where prices rose rapidly in the second half of the eighteenth century. If we compare the difference in price levels of exporting and importing regions not in absolute, but in relative terms, however, the picture seems to be the reverse (Figure 8). So despite the multiplicity of slave trade connections, slave trade routes from Indonesian Archipelago exporting regions and from South Asia to Batavia, as well as the Malabar trade route to the Cape of Good Hope all knew relative price level margins (expressed in guilders per 100 kilometre) that were higher than the Atlantic slave trade routes. Only for the slave trade from Batavia to the Cape of Good Hope this was not the case. Perhaps this high relative margin on Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago slave trade routes can be related to the curious fact that the VOC tried to monopolize many trading products, but never really tried to monopolize the trade in enslaved people. The VOC participated in the slave trade for its own labour supply, but left the slave trade open to private trade of burghers, Asian merchants and VOC-personnel. Were the absolute margins too low, requiring perhaps a too large volume in Company slave trade to make it attractive; or should we consider the reverse, namely that it were exactly these high relative margins that kept the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago slave trade thriving through a system of private trade, channelled both through Asian shipping and private trade of the crews and mostly captains and officers on East India Company ships? Just as these relative margins rose strongly in the Indian Ocean and especially the Indonesian Archipelago slave trade routes, slave trade price levels rose across the board in the Atlantic. One could wonder how this relates to the patterns of slave trade and price developments in different parts of the world. Does this reflect the stability of slave prices in Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago export regions? What does that tell us about patterns of enslavement and the ‘two-tiered price structure’ in those regions? And how does it relate to the development of slave trade?

Figure 8. Relative price differences on slave trade routes (guilders per 100 km).

Implications and further research

This article has provided a first reconstruction of the level of prices of enslaved human beings and their development in a number of important supplying and demanding slave trade regions in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago world and compared this to the Atlantic. Doing so, this article aims to contribute to our understanding of the multidirectional and complex early modern Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago slave trade in its global context. This study aims to stimulate and facilitate new global comparisons, between the Atlantic, Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago worlds, as well as within these regions. As we have seen in this article, these comparisons indicate that until the middle of the eighteenth century, the prices in the slave trade complex of the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago and that of the Atlantic world were not far apart and developed along similar lines. This is an important finding.

Although the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago were deeply connected by the slave trade, this slave trade complex was not directly connected to the Atlantic slave trade, except for the slave trade from the western Indian Ocean region to the Americas in the later parts of the eighteenth century. The congruent developments in slave trade prices in these different parts of the world are therefore striking. The clear distinction in price levels between slave importing and exporting regions indicates the important role of slave trade in the Atlantic as well as in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago. The middle of the eighteenth century in many ways marked a turning point. In the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago, price levels diverged increasingly not only between export and import regions, resulting in higher relative price margins, but also in more pronounced differences in price levels between South Asia and Southeast Asia. In the Atlantic world, the acceleration of the plantation system towards the end of the eighteenth century drove up prices even more rapidly, while relative price margins remained much lower, because prices in the supplying region of West Africa were also marked by a steady increase.

Although these indications on price levels are still relatively crude, this study has shown that the development of global series of slave trade prices is not only possible but also very useful to advance our knowledge of slavery and slave trade from a global historical perspective. Further research and data collection are necessary. A bright horizon remains to be explored. The slave trade was an important indicator of coerced mobility connecting different regions, exporting and importing slaves, as well as different slavery and bondage systems. The multi-directional character of the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago slave trade has several important implications for studying and especially reconstructing price levels. The development of this price data, however, shows that the patterns of slave trade and slavery in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian Archipelago worlds can and should be compared to the Atlantic world. These comparisons bring to light useful insights, not just into differences but also into similarities.

Matthias van Rossum is Senior Researcher at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam. He specializes in global labour history and the history of slavery and slave trade. He is (co-)leader of several research and infrastructure projects that explore the history of slavery and colonialism, such as Exploring Slave Trade in Asia and GLOBALISE.