Postpartum depression (PPD) affects nearly one in five childbearing women and is characterised by excessive sadness and anxiety, poor sleep and low motivation within the first year after childbirth.Reference Shorey, Chee, Ng, Chan, Tam and Chong1 Although screening for PPD at postpartum obstetric visits is recommended, suboptimal rates of postpartum visit attendance leave a large proportion of birthing parents with PPD at risk of not being identified or referred for appropriate treatment. As such, PPD screening within well-child paediatric care, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics at multiple time points during infancy, fills a critical gap in identifying postpartum psychiatric symptoms and supporting connections to appropriate care and treatment.Reference Rafferty, Mattson and Earls2 However, the efficacy of this system is predicated on robust disclosure of symptoms, a largely untested assumption in routine paediatric clinic encounters.

A widely used tool for assessing PPD is the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).Reference Levis, Negeri, Sun, Benedetti and Thombs3 Relative to depression diagnoses obtained from clinical interviews, the EPDS demonstrates high specificity and sensitivity in detecting PPD.Reference Levis, Negeri, Sun, Benedetti and Thombs3 We sought to examine the endorsement and reliability of PPD symptom disclosure in clinic encounters occurring as part of infant well-child care and in research encounters administered as part of a known study, using the EPDS to gain insight into the influence of screening context on symptom disclosure.

This analysis leveraged EPDS data collected from women taking part in a longitudinal study approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Pennsylvania and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.Reference Gur, White, Waller, Barzilay, Moore and Kornfield4,Reference Kornfield, White, Waller, Njoroge, Barzilay and Chaiyachati5 Individuals from that study with singleton births and two completed EPDS assessments within any 4-week period in the first year after birth were included (n = 183); the clinic encounters occurred at a mean of 10.8 weeks postpartum (s.d. 4.6) and the research encounters at 11.6 weeks (s.d. 3.8), with n = 113 participants (62%) completing the clinic encounter EPDS assessment first. In the research encounter, participants completed the EPDS at any time or place on their phone, tablet or computer. In the clinic encounter, parents completed the EPDS as part of their infant’s well-child care, generally on a tablet or phone in the paediatrician’s office. Of note, item 10 (thoughts of self-harm) was not administered in the research encounter owing to issues with monitoring self-harm virtually; no participant endorsed (defined as ‘yes, quite often’ or ‘sometimes’) this item in the clinic encounter.

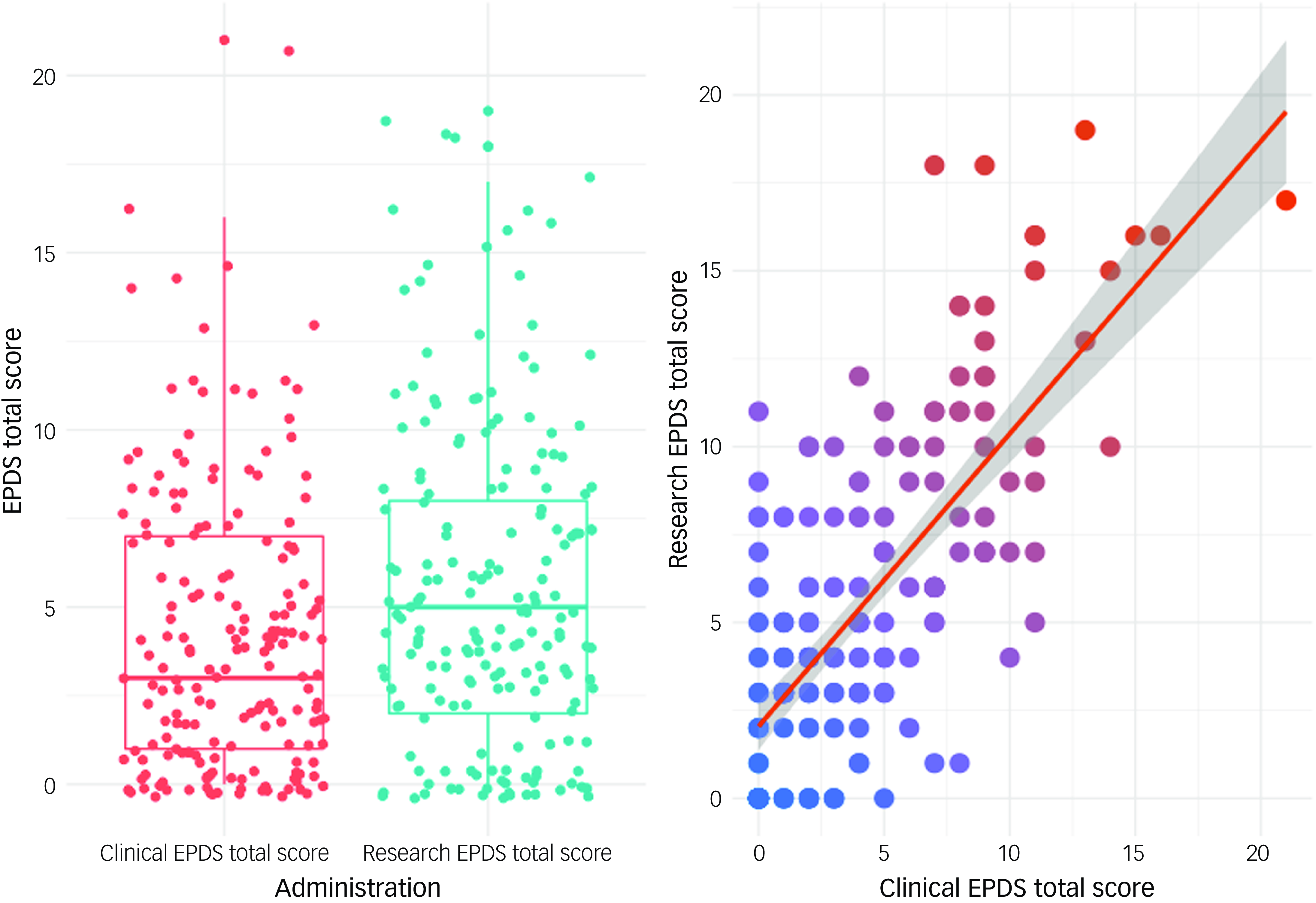

Reassuringly, total EPDS scores were highly correlated across encounter context according to Pearson’s correlation (r = 0.72, P < 0.001), with moderate reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.71). However, mean scores were significantly lower for EPDS clinic encounters versus research encounters (two-sided t-test: clinic, mean = 4.2, s.d. = 3.9; research, mean = 5.5, s.d. = 4.5; P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). When a screening threshold score of ≥10 was used to identify likely cases of PPD,Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky6 two-fold fewer participants screened positive at the clinic encounter (n = 17, 9%) compared with the research encounter (n = 36, 20%) on the EPDS (χ 2(1) = 24.05, P < 0.001). Thus, using the currently accepted screening threshold of ≥10, the EPDS was less likely to suggest PPD when completed during well-child care than when it was completed for research purposes. Concordance in EPDS scores across encounter contexts was higher when a threshold score of ≥8 for the clinic encounter (κ = 0.55, s.e. = 0.08, P < 0.001) was used than when a threshold score of ≥10 was used (κ = 0.33, s.e. = 0.09, P < 0.001).

Fig. 1 Postpartum depression Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) scores across clinical and research encounters. The graphs show means and distributions of EPDS scores by encounter setting and scatterplots of correlations of scores from the two encounters. Grey shading represents the 95% confidence level interval for predictions from the linear model of the relationship between total scores across the two encounters.

To increase detection, maternal depression screening is recommended as part of routine paediatric primary care. However, by comparing EPDS reports collected as part of routine paediatric well-child care with EPDS reports collected in a research encounter, we found that many women are likely to underreport PPD symptom burden during well-child visits, and PPD referrals may be missed when solely relying on screening in a paediatric clinical setting with currently accepted referral thresholds. Drivers for incomplete symptom disclosure may include factors such as the caregiver’s focus on the child as the patient, or a desire to be seen as a ‘good’ caregiver or other mental health stigmas.Reference Thornicroft, Sunkel, Alikhon Aliev, Baker, Brohan and El Chammay7 The current findings, coupled with existing known barriers, such as physician training, inadequate staff time, lack of referral plans and availability of mental health services, contribute to existing limitations of depression screening in paediatric clinics.Reference Hunt, Uthirasamy, Porter and Jimenez8 Although implementation of lower threshold scores could increase identification, there would be a trade-off with specificity, and it would require added clinical response and support. Additional work is needed to address insufficient identification, including further elucidation and intervention to address barriers to symptom disclosure and adequately support women’s needs.

The current analysis had several notable limitations. First, our results may not be generalisable. The data were drawn from a convenience sample recruited during the COVID-19 pandemic, which represented a unique contextual stressor for pregnant and postpartum women, and the timing of the clinic encounter was not standardised with respect to that of the research encounter. However, the order of EPDS encounters was balanced, and the encounters occurred within 4 weeks of each other, decreasing the likelihood that priming or timing significantly contributed to reported variations in symptoms. The convenience nature also limited analysis to participants accessing well-child care within one paediatric health system, and the sample was notable for having a small proportion (9%) without at least some college education. Second, we excluded the suicidality item from the EPDS version used for our research encounter, which reduced the range of possible scores. Notably, no participant endorsed this item during their clinic encounter, suggesting that the difference in our rates of threshold screens may be an underestimate of differential symptom disclosure. Third, we did not collect data on depression symptoms based on diagnostic interviews or alternative measures of PPD against which EPDS symptom disclosure could be compared. Moreover, although the EPDS is commonly used, concerns about high false-positive rates have been raised.Reference Matthey and Agostini9

In summary, this work suggests risk of inadequacy in current screening approaches and calls for a priori study designs in large, diverse populations to determine how to best support PPD symptom identification across venues in our shared efforts to meaningfully screen, connect and provide care at this vital junction.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, L.K.W., upon reasonable request.

Funding

All phases of this study were supported by the Lifespan Brain Institute at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Penn Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. L.K.W., R.E.W., W.F.M.N., and R.E.G. received support from National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) R01MH138428. B.H.C. reports grants from NIMH K08 career development award MH129657 during the conduct of the work. R.E.W., W.F.M.N., S.L.K. and R.E.G. received support from NIMH R01MH128593. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.