Introduction

Congenital long QT syndrome is a genetic condition causing delayed myocardial repolarisation, resulting in a prolonged QTc segment on a resting electrocardiography, which is associated with ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death. Reference Schwartz, Crotti and Insolia1 There are multiple causative genetic variants affecting three major genes, KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A, which account for three distinct phenotypic expressions of congenital long QT syndrome type 1 (LQT1), type 2 (LQT2), and type 3 (LQT3), respectively. Reference Tester and Ackerman2 These major genes account for eighty-five percent of affected individuals. Reference Tester and Ackerman2 The first-line suggested treatment for individuals affected by LQT1 and LQT2 is beta blockers, preferably non-cardioselective options such as Nadolol. Reference Han, Liu, Li, Qing, Zhai and Xia3 Due to the risk of potentially catastrophic sequelae, it is vitally important that patients affected by congenital long QT syndrome are adherent with their medications. We have previously identified a very low incidence of probands and cardiac events in our paediatric population, with cascade screening identifying most patients. Reference Kendall, Wright, Rea, Murray, Muir and Prendiville4 Despite a low event rate in Northern Ireland, ensuring adequate adherence is critical, as non-adherence has been linked to both ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death. Reference Chatrath, Bell and Ackerman5,Reference Vincent, Schwartz and Denjoy6 Adherence and risk factors associated with non-adherence have been investigated sparingly worldwide, Reference Krøll, Butt and Jensen7,Reference Waddell-Smith, Li, Smith, Crawford and Skinner8 never solely in a paediatric population. Factors including limited understanding, taste, formulation, family structure and increasing independence during adolescence can all potentially influence paediatric adherence. Reference El-Rachidi, LaRochelle and Morgan9 Unpleasant side effects of beta blockers, such as tiredness, dizziness, and depression, are well documented in children with cardiac conditions and may also contribute. Reference Sullivan, Pompa, Schieber, Arora, Dionne and Beach10 This study aimed to examine beta blocker prescription adherence in a paediatric cohort of individuals affected by congenital long QT syndrome.

Methods

Chart review identified children and young people with LQT1 and LQT2 using the inherited cardiac conditions database at the Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children and electronic patient records, yielding a total of 152 patients. Data collected included diagnosis, age, medication prescription including formulation, dose, and frequency, duration of corrected QT interval, implantable cardioverter defibrillator insertion, whether a sibling was also affected, if there was a history of sudden cardiac death in a parent, and sex.

Whilst some children continue to be diagnosed following cardiac events, most patients are identified by cascade screening, including clinical assessment, baseline resting electrocardiography and genetic testing. In ambiguous cases, an exercise stress test is performed, as the QTc prolongation in the recovery period can aid diagnosis. Diagnosis is made based on the presence of a prolonged QTc interval (and/or abnormal T waves) on a resting electrocardiography or during recovery of an exercise stress test. Genetic testing is also performed, and a diagnosis can be aided by the presence of a known pathological variant. Historically, our departmental practice has been to treat patients with normal QTc duration with a known pathological variant, although we are aware that some specialist centres are now reporting that low-risk individuals may not require regular medicine. Reference MacIntyre, Rohatgi, Sugrue, Bos and Ackerman11 Follow-up at our centre for all patients includes regular clinical review, with Holter monitoring and exercise stress tests performed for further monitoring.

Although nadolol is considered superior to other beta-blockers in LQT1 and LQT2, Reference Han, Liu, Li, Qing, Zhai and Xia3 its availability in paediatric formulations was very limited in Northern Ireland during the study period. Consequently, the common practice over the studied period was to prescribe propranolol for neonates and infants due to its well-documented tolerability. Reference Sanatani, Potts and Reed12 As children grew older, they were typically transitioned to atenolol, and later, teenagers and young adults were switched to bisoprolol, with the aim of reducing dosage requirements (twice a day for atenolol and once a day for bisoprolol) in order to improve adherence and prevent disruption to school routines. Propranolol was in a liquid formulation; atenolol was either a liquid or tablet, bisoprolol was a tablet, and nadolol was in a liquid formation.

Adherence and the factors influencing it were the primary outcomes of interest of this study. We hypothesised that multiple factors could potentially influence adherence. To assess adherence, individual practice pharmacists based at the general practice surgeries were contacted via telephone, and a history of repeat prescriptions over a year’s period (December 2023 to November 2024) was obtained. Using the prescription data, a medication possession ratio for the year was calculated. The medication possession ratio is a tool used to gauge adherence where a ratio is calculated for the number of days in each period that a patient has a supply of their medication. It is calculated by dividing the sum of days with prescribed medicine by the total number of days in the study period (see Figure 1). In the case that a medicine is taken multiple times a day, this is factored into the calculation, e.g., the total quantity of medication provided divided by total daily dose gives the sum of days with prescribed medicine. Deprivation was assessed by cross referencing the patient’s postcode to the Northern Irish Multiple Deprivation Measure. 13 The Northern Irish Multiple Deprivation Measure calculates a composite rank between 1 and 890 based on seven distinct aspects of deprivation and gives a post-code a composite score. For simplicity, this score was converted to a deprivation decile, with 1 being most deprived and 10 least deprived.

Figure 1. Medication possession ratio formula

![]() $MPR = SDPM \div TND 0$

. (MPR) Medication possession Ratio (SDPM) sum of days with prescribed medication, (TND) total number of days in study period.

$MPR = SDPM \div TND 0$

. (MPR) Medication possession Ratio (SDPM) sum of days with prescribed medication, (TND) total number of days in study period.

All data was anonymized and imported to SPSS (Version 30, IBM, New York). Descriptive statistics and frequencies were calculated. Normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro Wilk Test. As parametric assumptions were not satisfied continuous variables were reported as medians with an interquartile range. For comparisons of continuous data the Mann-Whitney U test was used. A Medication possession ratio value of ≥0.8 was chosen as being indicative of “adequate adherence” and lower than 0.8 was considered “poor adherence.” This cutoff of ≥0.8 has been used in multiple other studies examining adherence in the literature. Reference Waddell-Smith, Li, Smith, Crawford and Skinner8,Reference Adeyemi, Rascati, Lawson and Strassels14 A value of ≥1.0 was used to represent ideal adherence. Potential risk factors for poor adherence were analysed using multivariable binary logistic regression, odds ratios were calculated and the 2-sided p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. In addition to deprivation, QTc duration >470 ms, sex, age, medication prescribed (as there was only one patient on nadolol this was censored), having a sibling affected and proband status were all included as variables in the model. Due to the low burden of definite arrhythmic events (N = 1) in our cohort (which prompted an implantable cardioverted defibrillator insertion) this was not included as a variable.

Results

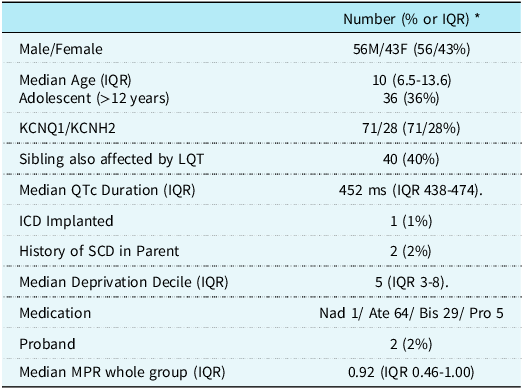

Ninety-nine patients’ data was obtained (71 affected by LQT1 and 28 affected by LQT2) (the remaining 53 were excluded due to incomplete data/no response from their general practice pharmacist) and included giving a study follow-up duration of 36,135 patient days (see Table 1). There were 56 boys and 43 girls, and the median age was 10 years interquartile range (6.5–13.6). Most patients (70%) were diagnosed with LQT1 and had a relevant variant in KCNQ1. Just under half (45%) of the cohort had a sibling who was also affected with congenital long QT syndrome. The median corrected QT duration (QTc) by Bazett’s formula was 452 ms (IQR 438–474). One patient had an implantable cardioverter defibrillator implanted, and two patients had lost a parent to sudden cardiac death. No patients from our cohort underwent left cardiac sympathetic denervation over the period examined.

Table 1. Patient characteristics

* Unless otherwise noted. Ate Atenolol, Bis Bisoprolol, ICD Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator, ms milliseconds, IQR Interquartile Range MPR Medication Possession Ratio, Nad Nadolol, Pro Propranolol, QTc Corrected QT Duration SCD Sudden Cardiac Death.

One patient was prescribed nadolol, sixty-four were prescribed atenolol, 29 were prescribed bisoprolol, and five were prescribed propranolol. The median deprivation decile was 5 (IQR 3–8). The median medication possession ratio was 0.92 (IQR 0.46–1.00), 56 patients (57%) had at least adequate adherence (≥0.8), and 44 of these patients had ideal (≥ 1). Conversely, 43 patients (43%) had adherence <0.8, and there were six patients (6%) who were completely non-adherent over the study period examined. Two patients (2%) in the cohort were the proband for their families.

Of note, there was no statistically significant difference between the median MPR of the two largest medication groups, atenolol 0.84 (IQR 0.37–1.0) and bisoprolol 0.92 (IQR 0.55–1.0) (p = 0.54). Of the 64 patients prescribed atenolol, 43 (67%) were prescribed it in a liquid formulation and 21 as a tablet. The median MPR for those on liquid preparation was 0.83 (IQR 0.31–1.0), and for those on tablets, the MPR was 0.84 (IQR 0.52–1.0); this was also not statistically significant (p = 0.816).

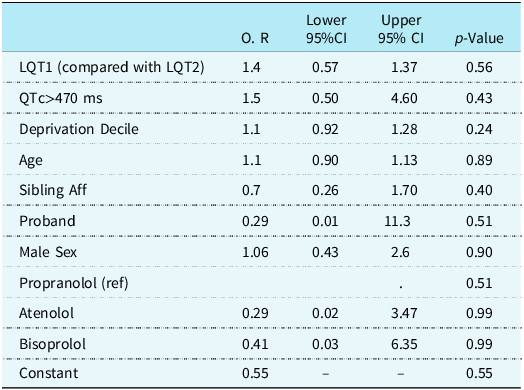

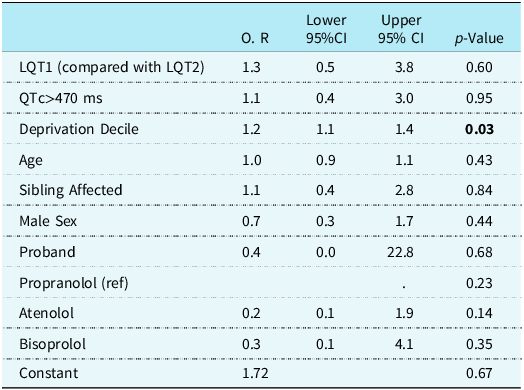

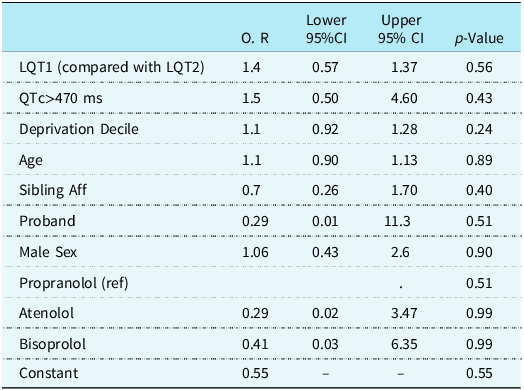

Risk factor analysis was performed by using multivariable binary logistic regression analysing risk factors for adequate and ideal adherence (see Tables 2 and 3). Adequate adherence is broadly agreed to be 0.8 in the literature. Given the risk of death associated with non-adherence, it was decided by the investigative team to also examine ideal adherence. Factors included QTc > 470 ms, patient age, sex, subtype of LQT syndrome, being the proband, whether a sibling was affected, deprivation decile, and current medication prescribed. No factors were significantly associated with adequate adherence. Decreased deprivation was associated with increased odds of ideal adherence (OR 1.2, P = 0.03).

Table 2. Multivariable binary logistic regression analysing potential risk factors for adequate adherence (MPR<0.8).

(CI Confidence Interval Dep Deprivation Decile, O.R Odds Ratio, QTc Corrected QT interval, Sibling Aff Sibling with LQTS).

Table 3. Multivariable binary logistic regression analysing potential risk factors for ideal adherence (MPR≥ 1.0)

(CI Confidence Interval Dep Deprivation Decile, O.R Odds Ratio, QTc Corrected QT interval, Sibling Aff Sibling with LQTS).

Discussion

This study presents novel findings regarding prescription adherence in a paediatric cohort affected by congenital long QT syndrome. The median medication possession ratio (0.92) was superior to the quoted value of “adequate adherence” of 0.8. This differs from the medication possession ratio in a study including both adults and children with congenital long QT syndrome in New Zealand. Reference Waddell-Smith, Li, Smith, Crawford and Skinner8 Risk factor analysis found decreasing deprivation to be predictive of ideal adherence; although small, the effect size was statistically significant. Similar findings have been seen in paediatric patients post liver transplant with greater deprivation. Reference Wadhwani, Bucuvalas and Brokamp15 Lower socio-economic status is also associated with lower medication adherence in hypertensive patients. Reference Kressin, Orner, Manze, Glickman and Berlowitz16 Potential reasons for increasing deprivation being associated with poorer adherence could include fewer GP appointments, Reference Butler, O’Donovan, Johnston and Hart17 lower educational attainment and understanding of parents Reference Brennan, Moore and Millar18 and increased incidence of parental ill health. 19 Worldwide the effect of race has been well documented, with Caucasian groups generally having higher adherence. Reference Adeyemi, Rascati, Lawson and Strassels14,Reference Salt and Frazier20 Race was not factored into our analysis, as 97% of the population of Northern Ireland is Caucasian, 21 and when examining a rare condition like congenital long QT syndrome in the paediatric population, there was concern that these patients would potentially be identifiable. The observed association between socioeconomic deprivation and lower adherence could conceivably inform patient interventions such as tailored education events or reminder systems in clinician-identified high-risk groups. Such interventions would ideally factor in parental and patient preferences to maximise improved adherence. Reference Fenerty, West, Davis, Kaplan and Feldman22

Age was not significantly associated with adherence in our cohort; this contrasts somewhat with other studies examining adherence in children with diabetes, Reference Adeyemi, Rascati, Lawson and Strassels14 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Reference Barnard-Brak, Marques and Kudesey23 and inflammatory bowel disease, Reference Barker, Shapiro, Lobato, McQuaid and Leleiko24 all of which found that adolescents have poorer adherence. Additionally, a mixed inherited cardiac condition questionnaire study found younger patients were more likely to report non-adherence compared with older patients with the same condition. Reference Sanatani, Potts and Reed12 In a condition that is potentially fatal in cases of poor adherence, Reference Kendall, Wright, Rea, Murray, Muir and Prendiville4 “adequate” adherence should ideally be 100%. As a time of increasing maturity and independence, adolescence is well documented as a challenging time to ensure a patient transitions to taking responsibility for their own health. Reference Sawyer, Drew, Yeo and Britto26 It may be that in the teenage population of our cohort we are missing non-adherence, as their parents are still collecting their medications from the pharmacy.

Formulation and side effects have previously been shown to affect paediatric adherence, especially if a medicine has a bitter or bad taste. Reference El-Rachidi, LaRochelle and Morgan9 We found no statistically significant difference between the two forms of atenolol. Patient and parent feedback regarding palatability was not obtained for this study but should inform prescribing considerations, and if a medicine is not tolerated, alternatives should be considered. Reference El-Rachidi, LaRochelle and Morgan9

Unlike many other conditions, congenital long QT syndrome is asymptomatic, where the effects of non-adherence would not necessarily be noticeable, potentially until affected by ventricular arrhythmia or sudden cardiac death. Anxiety and fear in both parents Reference Farnsworth, Fosyth, Haglund and Ackerman27 and young people Reference Last, English, Pote, Shafran, Owen and Kaski28 affected by inherited cardiac conditions is well documented. It would be reasonable, therefore, to assume that the presence of a sudden cardiac death in the family may be associated with increased adherence. However, this was not examined in our cohort due to a low incidence of sudden cardiac deaths in relatives.

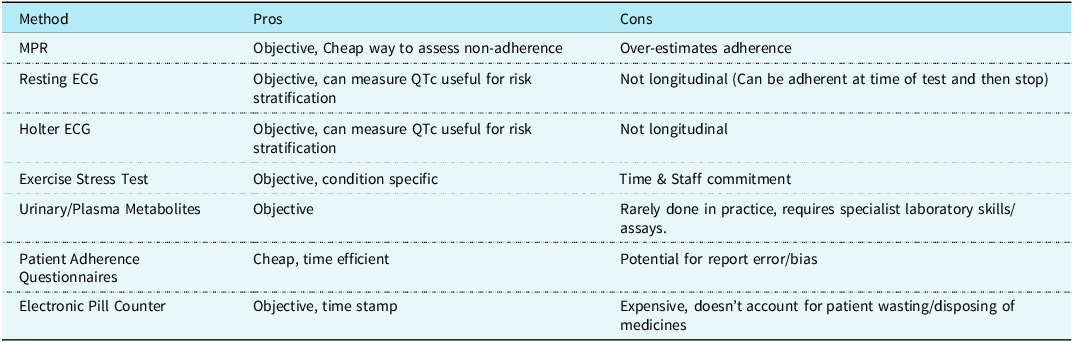

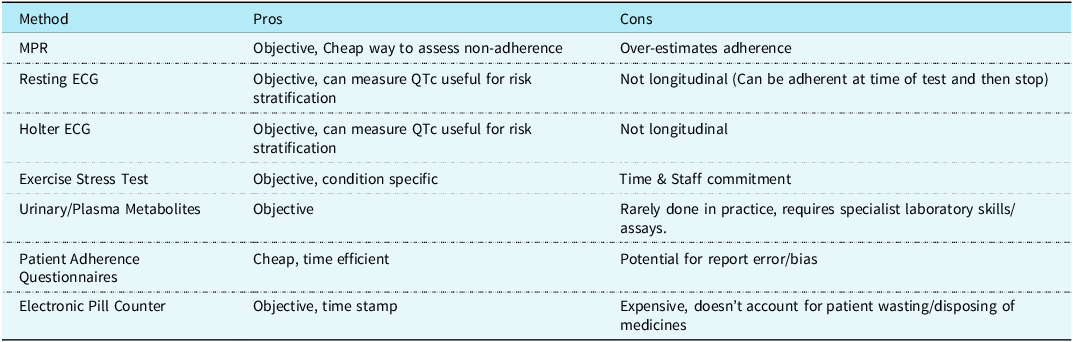

Adherence is intrinsically a difficult aspect of patient behaviour to measure, and whatever method is chosen will have strengths and weaknesses (see Table 4). Medication possession ratio strengths include its objectivity as to whether a patient has picked up a prescription or not and ability to objectively assess non-adherence (e.g., in the case that no scripts have been filled at all), highlighting families who may require further consultations/intervention to explore the reasons for the non-adherence. A major drawback is that a patient collecting a prescription does not ensure that they are taking medication. This and not factoring in the gaps between collections means it tends to overestimate adherence. Reference Lam and Fresco29 Urinary metabolites or plasma concentration Reference CitePloegmakers, van Poelgeest, Seppala, van Dijk, de Groot, Oliai Araghi, van Schoor, Stricker, Swart, Uitterlinden, Mathôt and van der Velde30 could be measured; however, this has cost implications and requires local laboratory expertise. Other methods of monitoring include blunted heart rate response on exercise stress testing, Reference Chen, De Souza, Franciosi, Harris and Sanatani31 which also provides useful clinical data, but the requirement for cardiovascular laboratory staff time potentially limits how often this can realistically be measured on a per-patient basis. Routine electrocardiography performance as well as Holter monitoring is standard surveillance and certainly helpful but can only give cross-sectional information and does not inform about adherence longitudinally. There are many patient questionnaires that can also be used to measure adherence, including disease-specific paediatric examples. Reference Quittner, Modi, Lemanek, Ievers-Landis and Rapoff32 However, these methods have the usual concerns regarding reporter error and/or bias.

Table 4. Potential methods of monitoring patients with LQTS adherence

(MPR Medication Possession Ratio).

Limitations

This study has several limitations, including its retrospective nature as well as the limitations highlighted with the method of measuring adherence as outlined above. Although it is a relatively large cohort of paediatric patients for a rare disease like congenital long QT syndrome, it may be underpowered for significant risk factors for non-adherence. Its external validity to patients more severely affected or with a higher proportion of probands may also be limited, as this is a cohort primarily identified by familial screening who generally have a milder phenotype. Another potential risk factor we did not examine in a largely asymptomatic group may be time from diagnosis; this was not examined due to the risk of it acting as a confounding variable in a model that included age. Of a potential cohort of 152, comprehensive data was only able to be collected for 99, which may introduce an availability bias. We were only able to compare formulations of atenolol, as this was the only medicine available in both a liquid and tablet preparation.

Future research could include prospective randomised controlled trials evaluating electronic reminder tools for high-risk families, aimed at improving medication adherence and prescription collection. Qualitative interviews with caregivers and children from deprived backgrounds may help identify specific barriers that can be addressed by the multidisciplinary team. Finally, multi-centre cohort studies would enhance the generalisability of findings across diverse settings.

Author contributions

SK Concept, data collection and analysis and first draft.

SN, AJ, BC

Data collection & editing

MD

Data analysis and editing

TP/PM/FC/BC

Editing

All authors approved the final draft of the article.

Financial support

SK is supported by the Belfast Trust Charitable Funds.

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standard

This study was registered with the Belfast Trust audit department. Audit number 6885.