Introduction

There are wide variations in the quality of relational experiences within stroke units for patients and relatives: from collaborative and empowering relationships to those that are restrictive, authoritarian and undignified (Luker, Lynch, Bernhardsson, Bennett & Bernhardt, Reference Luker, Lynch, Bernhardsson, Bennett and Bernhardt2015; Peoples, Satink & Steultjens, Reference Peoples, Satink and Steultjens2011). Patients and relatives describe an emotionally intense time following a stroke, with feelings of loss and vulnerability; changes in self compared to before the stroke; and existential questions around the meaning of life after stroke (Ellis-Hill & Horn, Reference Ellis-Hill and Horn2000; Lawton, Haddock, Conroy, Serrant & Sage, Reference Lawton, Haddock, Conroy and Sage2016; Lynch et al., Reference Lynch, Luker, Cadilhac, Fryer and Hillier2017; Ryan, Harrison, Gardiner & Jones, Reference Ryan, Harrison, Gardiner and Jones2017). These issues are rarely considered and, are therefore, even less likely to be addressed in acute in-patient stroke services.

Within the United Kingdom (UK), a person- or patient-centred approach is most commonly reported to be used in stroke units which reflects current UK National Health Service (NHS) policy (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Sims, Hewitt, Joy, Brearley, Cloud and Ross2013; Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, Haddock, Conroy and Sage2016; NHS England, 2019; NHS Scotland, Reference Scotland2019; Rosewilliam, Sintler, Pandyan, Skelton & Roskell, Reference Rosewilliam, Sintler, Pandyan, Skelton and Roskell2016). However, there is a disconnect between the conceptual thinking underpinning person-centred approaches and its interpretation in practice (Bombeke et al., Reference Bombeke, Symons, Debaene, De Winter, Schol and Van Royen2010). There has been a parallel, but more limited, interest in the development of relationship-centredness (Dewar & Nolan, Reference Dewar and Nolan2013; Nolan, Davies, Brown, Keady & Nolan, Reference Nolan, Davies, Brown, Keady and Nolan2004; Smith, Dewar, Pullin & Tocher, Reference Smith, Dewar, Pullin and Tocher2010; Tresolini & The Pew-Fetzer Task Force, Reference Tresolini1994) which is based on the following principles: (i) healthcare relationships includes the personhood of all those involved; (ii) affect and emotion are important components of healthcare relationships; (iii) relationships are constructed together with reciprocal influence; and (iv) maintaining genuine relationships are necessary for health and recovery, and are morally valuable (Soklaridis, Ravitz, Adler Nevo & Lieff, Reference Soklaridis, Ravitz, Adler Nevo and Lieff2016). This creates a subtle shift in perspective on the same issues.

Researchers have found a connection between the organisational context and culture in which care is delivered and the healthcare teams’ ability to build relationships (Aadal, Angel, Langhorn, Pedersen & Dreyer, Reference Aadal, Angel, Langhorn, Pedersen and Dreyer2018; Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, Haddock, Conroy and Sage2016; Ocloo et al., Reference Ocloo, Goodrich, Tanaka, Birchall-Searle, Dawson and Farr2020). It has been found that a focus on tasks or targets can reduce the quality of relationships (Greenwood & Mackenzie, Reference Greenwood and Mackenzie2010; Lawrence & Kinn, Reference Lawrence and Kinn2011; Rosewilliam et al., Reference Rosewilliam, Sintler, Pandyan, Skelton and Roskell2016; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Harrison, Gardiner and Jones2017). Also, when relationships are perceived to be more mutual, that is: equal and collaborative with opportunities for choice and negotiation, the quality and meaningfulness of experience improves and patients’ engagement and recovery are enhanced (Creasy, Lutz, Young, Ford & Martz, Reference Creasy, Lutz, Young, Ford and Martz2013; Luker et al., Reference Luker, Lynch, Bernhardsson, Bennett and Bernhardt2015; Ocloo et al., Reference Ocloo, Goodrich, Tanaka, Birchall-Searle, Dawson and Farr2020).

A lifeworld-led approach takes the idea of mutuality even deeper and focuses on how reality arises between the outer and inner subjective world through awareness and ongoing consciousness in human experience (Galvin & Todres, Reference Galvin and Todres2013). This contributes an innovative perspective to healthcare relationship theory and offers new ways to consider, and respond to, the existential issues faced by patients and relatives. Lifeworld-led approaches have been developed from phenomenological analyses of the meaning of care, being human, well-being and suffering (Dahlberg, Todres & Galvin, Reference Dahlberg, Todres and Galvin2009; Todres, Galvin & Dahlberg, Reference Todres, Galvin and Dahlberg2007). By focusing on the fully human response, considering embodied as well as cognitive knowing, a lifeworld-led approach considers the tacit and embodied nature of what it feels like to be human through the human body’s inherent ability to acquire and convey meaning within the process of relationship construction and human connection.

Researchers call for the stroke discipline to acknowledge the importance of therapeutic relationships in the emotional well-being and recovery of stroke patients, their relatives/carers, and for multidisciplinary team (MDT) working (Bennett, Reference Bennett2016; Burton, Fisher & Green, Reference Burton, Fisher and Green2009). There is a growing evidence base for the development of therapeutic relationships particularly with people living with aphasia following a stroke (Bright & Reeves, Reference Bright and Reeves2020; Hersh, Godecke, Armstrong, Ciccone & Bernhardt, Reference Hersh, Godecke, Armstrong, Ciccone and Bernhardt2016; Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, Haddock, Conroy, Serrant and Sage2018); however, in the UK the development and maintenance of relationships within in-patient stroke services is limited. There is still a strong focus on biomedical needs and organisational priorities (Taylor, Jones & McKevitt, Reference Taylor, Jones and McKevitt2018). This study aimed to explore and describe the processes within an innovative approach focused on relationship-centred care, informed by a lifeworld-led approach, which aimed to enhance human connection and clinical practice on stroke units. This study’s specific research questions reported here are:

-

How do patients, their relatives/carers and staff on stroke units describe their meaningful relational experiences?

-

How do staff describe positive inter-colleague relations that enable them to create and maintain meaningful relationships in clinical practice?

-

What are the processes that enrich relationships for all?

Research design

An Appreciative Action Research (AAR) design was used, which combines the strengths from two research approaches: appreciative inquiry and action research (Dewar, McBride & Sharp, Reference Dewar, McBride, Sharp, McCormack and McCance2017; Egan & Lancaster, Reference Egan and Lancaster2005). It integrates the appreciative inquiry principles of generativity, imagination and attention to language to construct relational realities with the focus on collaborative action, experimentation and practical orientation of action research (Dewar et al., Reference Dewar, McBride, Sharp, McCormack and McCance2017). It uses the generative principles of appreciative inquiry (Cooperrider, Whitney & Stavros, Reference Cooperrider, Whitney and Stavros2005) to focus on existing strengths and what is working well, rather than a conventional problem-focus. In addition, the practical orientation of action research in which new knowledge is generated through cycles of collaborative action and reflection produces situationally relevant knowledge about practice for practice (Herr & Anderson, Reference Herr and Anderson2014; Sharp, Dewar, Barrie & Meyer, Reference Sharp, Dewar, Barrie and Meyer2018).

Setting and participants

The study was conducted consecutively over two sites, site one for 10 months and site two, 5 months. Both sites were district general hospitals with 400–500 beds and provided acute and rehabilitation care on combined specialist stroke units. Four staff from both sites were already known to CG.

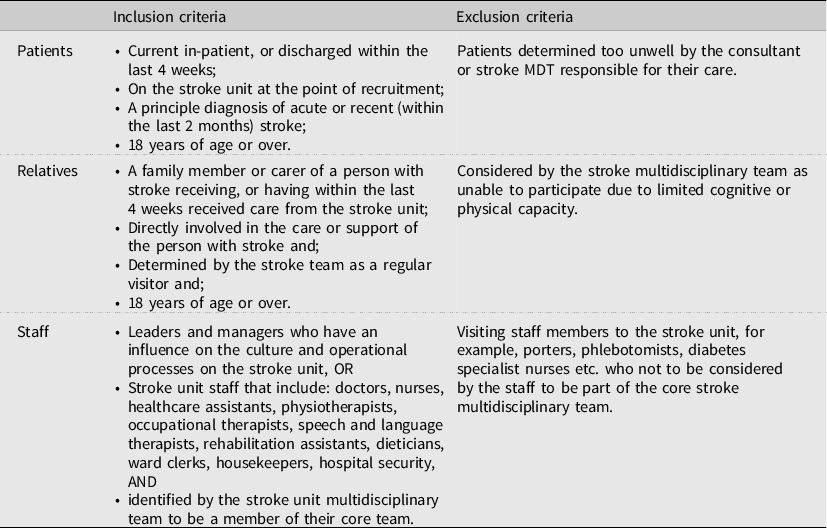

Inclusion criteria were as broad as possible. Exclusions were based on ethical considerations, for example, patients who were dying (Table 1). All staff from both MDTs were invited to participate through ward information meetings and posters in the staff room. Sixty-five staff who self-identified as belonging to the stroke MDT including managers (3), doctors (8), registered nurses (22), physiotherapists (4), occupational (6) and speech therapists (2), non-registered staff including therapy assistants (5), nursing assistants (13) and ward clerks (2) took part. Seventeen patients with stroke (12 female, age range 46–55 years to 86–95 years, median 76–85 years; 9 assessed by clinical team as having cognitive or communication difficulty, or both) and seven relatives [4 female; husband (3), wife (3), daughter (1); 76–85 years (4), 66–75 years (2) 56–65 years (1)] took part. Demographic information was collected at the time of consent. Participants engaged with the process to different extents – patients and relatives were recruited at different stages as they all chose to stop participating once they had left the stroke units. Staff engaged with the process as they wished – some participated in general discussions and observations, and, as the study progressed, a core group of six staff (n = 4 Site 1, n = 2 Site 2) developed a more active role in data generation and facilitating practice developments.

Table 1. Participant Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Ethical considerations

The study gained ethical approval from the NHS Health Research Authority (reference number 16/LO/0085) and the Lead Researcher’s University. Procedures were in place to support inclusion of patients with severe communication and cognitive impairment or low levels of consciousness; including supported communication and ‘aphasia friendly’ participant information, or if the patient was unable to understand the study information, their relative was consulted in line with the UK Mental Capacity Act (2005).

The process

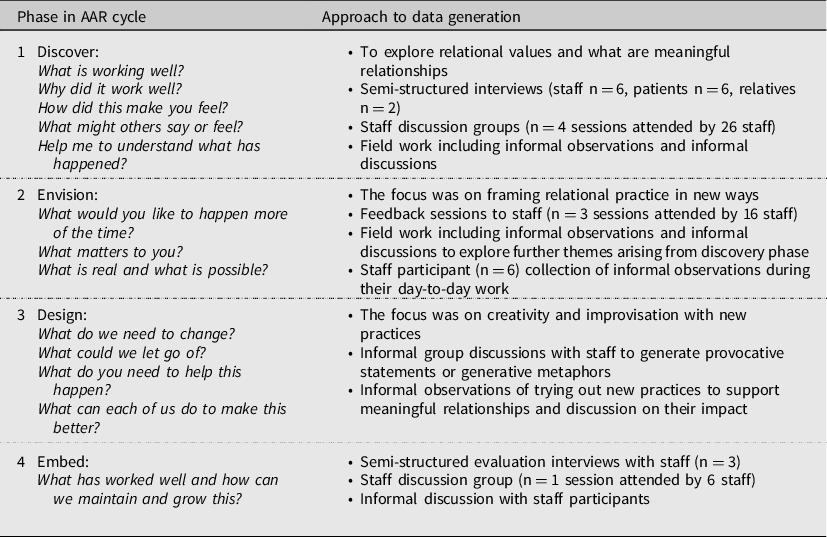

The AAR process is a cyclical process consisting of four phases: discover, envision, design and embed, with iterative cycles of feedback, reflection and evaluation at each phase (Dewar et al., Reference Dewar, McBride, Sharp, McCormack and McCance2017). A detailed description of data generation at each stage can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2. Approaches to Data Generation

On the first site, the inquiry and data generation were conducted over 10 months in 2016–2017 and for the second site, over five months in 2017. Data generation mainly took place within the ward: in the patient bays; around the nurse’s station and the day room/dining room. Data generation methods are outlined in Table 2 and included informal observation, informal discussions, discussion groups and semi-structured interviews. The cyclical AAR phases blended into each other rather than being separate phases of activity. Some cycles occurred within one conversation, others occurred over several months, and cycles occurred within cycles. The Discover phase focussed on uncovering, describing and appreciating what was working well, in relation to what was most meaningful and valued about relationships with others on the stroke unit; how participants felt during these meaningful experiences and; exploring what enabled these valued relationships to be created. In the Envision phase, data were fed back and explored with the participants to create collective ideas on what staff, patients and relatives would like for the future. This is a creative process imagining possibilities within the strengths identified through Discovery. In the Design phase participants co-created practical and real ways in which the type of relationships they valued could happen more often, sharing how would they feel, what would they think or do differently, or keep the same. These were a combination of personal and team-level changes. The final Embed phase used feedback and reflection alongside trying out new practices to evaluate if the new understandings and ways of working achieved their vision and how this could be maintained and further developed. The iterative cyclical AAR process continued until there was an understanding of the underlying processes within the staff participants’ relational practice and staff described a transformational change in their practice. Over 400 hours of observations and discussions were conducted over the two sites. Data from the first site provided tentative principles and insights into processes that supported humanising relationship-centred practice that were explored further and evaluated in the second site.

Data generation and analysis

Data generation was mainly conducted by CG, with six staff co-facilitators generating data in the final stages on both sites. Data generation and analysis were informed by relational constructionist and lifeworld-led care perspectives (Galvin & Todres, Reference Galvin and Todres2013; McNamee & Hosking, Reference McNamee and Hosking2012). Relational constructionism centres multiple, simultaneous relational processes, rather than individual actions, and views language as one of many ways in which inter-acting can occur. It recognises that language, gestures, and artefacts derive their significance in the ways they are used to construct relationships (Hosking, Reference Hosking2011; McNamee, Reference McNamee and Hosking2012). Therefore, relational constructionism expands the scope of relationship construction to be more-than-words, for example, tacit and embodied aspects of human relationships.

Todres’ (Reference Todres2007, Reference Todres2008) aesthetic dimension of sense-making was used to attend to the tacit, embodied aspects of human relationships during data generation and analysis. Galvin and Todres (Reference Galvin and Todres2013) developed the concept of aesthetic sense-making to describe the type of knowing that can guide humanly sensitive practice – termed ‘embodied relational understanding’. Data generation and analysis drew on this approach to consider data that were emotionally impactful or elicited an embodied response (felt-sense) for either the researcher or participants. This enabled sensitivity towards what was humanly meaningful.

Data analysis was a fluid, embodied and engaged process that occurred in every action cycle. There were two main parallel processes: (i) collaborative co-participant analysis in which participants and the researcher re-read data extracts or discussed in-the-moment after an observed interaction to make sense of the meaning and generate themes and patterns to inform their future action (Savin-Baden, Reference Savin-Baden2004); (ii) researcher-led analysis performed by author CG, along with reflective discussions with authors CEH and BD, used immersion crystallisation to further summarise and group themes across the data from both sites (Borkan, Reference Borkan, Crabtree and Miller1999).

Trustworthiness and reflexivity

This study’s trustworthiness and rigour focused on the interrelationship between (i) the participatory nature of AAR (Herr & Anderson, Reference Herr and Anderson2014); (ii) understanding the co-participants and the researcher’s role in influencing the context in which they are co-creating (McNamee & Hosking, Reference McNamee and Hosking2012; Sharp et al., Reference Sharp, Dewar, Barrie and Meyer2018) and; (iii) transparency around the process of data generation and analysis (Fossey, Harvey, McDermott & Davidson, Reference Fossey, Harvey, McDermott and Davidson2002). This was achieved through ongoing reflexive conversations on how the researcher and co-participants were ‘going on together’ by exploring each other’s roles in the process of creating any action, inter-action or non-action. We aimed to include many different perspectives such as ‘hidden voices’ of patients with cognitive or communication deficits or consideration of hierarchies within staff groups (Hosking & Pluut, Reference Hosking and Pluut2010; Sharp et al., Reference Sharp, Dewar, Barrie and Meyer2018). Ensuring transparency within analysis was achieved through collaborative analysis processes. CG conducted analysis on the wards to facilitate seeking regular sense-checking and feedback from participants. Generated tentative themes informed subsequent AAR cycles and were presented for feedback on ward notice boards accessible to patients, relatives, and staff. This enabled the researcher and co-participants to act with greater awareness of the possibilities available, their role in influencing relational practice and increase transparency in the choices made to develop practice.

Findings

The findings reported in this paper focus on understandings of what is most valued about relationships within the stroke units and the processes that can support and nurture these meaningful relationships. Firstly, the findings suggest that all participants (patients, relatives and staff) valued similar relational care experiences: described as connecting with each other at a human level – human connection. Secondly, there appeared to be specific processes leading to co-creation of human connections and their significance for patients, relatives and staff. Both will be described in more detail below. Pseudonyms have been used throughout.

Moments of human connection

Meaningful relational experiences happened when participants connected with each other at a human level. This was when the usual social boundaries and concerns dissolved and participants dropped into a space where deep and/or meaningful ways of being together as human to human could be shared. One nurse described this as, ‘giving something of your essential self’ (Nurse, Interview) that was more than their professional role. These moments could be shared as a group. Joanna, a Therapy assistant, recalled when she and some nurses were laughing with a group of patients while they demonstrated yoga positions from a class they attended the night before, ‘I think that it was a gelling moment, it was like a bonding. The patients saw these nurses and the rest of the staff as human beings, they are not just these coloured uniforms that go round checking charts all the time and drawing curtains’ (Therapy assistant, Interview). When in this space, their humanity could be shared and recognised and, through this recognition, a bond was created.

Moments could be created between individuals. Susan, a nurse, recalled how through offering her humanity through singing a song, she co-created a connection while caring for a patient (Ingrid) who was drowsy after her stroke, ‘I started to sing an Irish song with Ingrid, I didn’t know that she knew any Irish songs, it was just one I liked. Ingrid joined in and carried on the words. It made me feel lovely (smiling)’ (Nurse, Observational notes). While caring for Ingrid, the nurse felt comfortable enough with the patient to start singing. When Ingrid started singing it revealed her own humanity and a small part of herself to the nurse, providing recognition and a human response, creating an opportunity of being-in-relation by singing together.

Moments can also be created when the world as it is usually known is disrupted and finding meaningful ways to be together as human to human is paramount. A patient described connecting with member of staff through touch – especially significant for the patient as she was experiencing hallucinations and cognitive difficulties after her stroke, ‘It’s very difficult if you are having what they think are hallucinations. And you don’t know what that means even. So it is very, very difficult. Holding hands, when it happens, is extremely important. It really is enormously reassuring and it makes you feel that you’re OK, that life is alright and goes on, and you’re not really going out of your brain. It is terrifically important’ (Patient, Interview). The human connection created reassurance that they were both sharing the same world.

Entering healthcare is often entering the unknown and meaningful moments are those which recognise and support the human needs of those involved. A patient was sharing a joke with two healthcare assistants about how tall he was, while having assistance to transfer into a chair. His daughter, who had accompanied him on his entry to the ward, commented, ‘You need to laugh in a place like this. He loves his banter. His grandsons always give him a really hard time, so he will love this’ (Relative, Observation notes). Immediately recognising his love of banter and laughter was a key part of reassuring his daughter that the staff were tuned into his human needs and that his way of ‘being-in-the world’ would be supported.

As well as being experienced in dyads or groups, human moments could be experienced vicariously through observing or hearing about moments experienced by others. Moira, a staff nurse, had just observed another colleague with a patient and said, ‘Can I just say that was lovely, treating that lady with compassion, it was lovely. It made me feel warm, seeing a colleague with the same heart (as me), they have a genuine interest in people’ (Nurse, Observational notes). Human connection led to feelings of well-being at the time and for others who were observing or hearing about them. They appeared to support a sense of well-being and togetherness that was held in the shared experience, whether in person or vicariously.

Processes enabling human connections

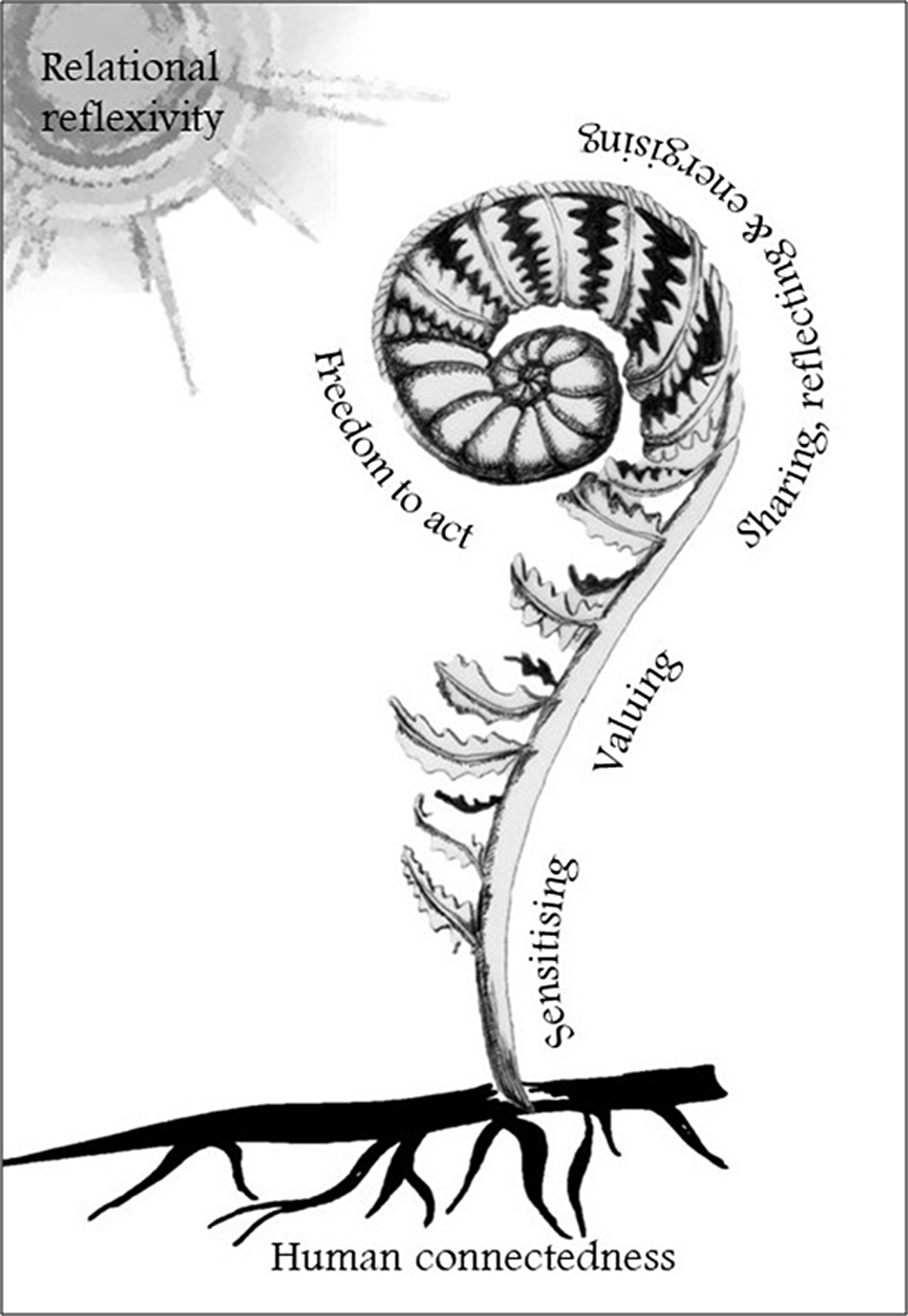

Through the action of participating in the AAR cycles, staff participants increasingly viewed their work as a relational activity full of possibilities for human connections. There were four orientating themes supporting humanising relational practice: (1) Sensitising to human connections; (2) Valuing human connections within the stroke unit space; (3) Sharing and reflecting that energises the team towards nurturing human connections; and (4) Having the freedom to act relationally.

The process appeared to start with sensitising to human connections and ultimately developed into more freedom to act relationally within the stroke unit space. The processes appeared to unfurl over time and, to denote this process, is illustrated in Fig. 1 as an unfurling fern.

Figure 1. Orientating processes of humanising relational knowing.

Sensitising to human connections

Sensitising involved heightening awareness of one’s relational self (one’s sense of self that is shared and co-created with others who you are in relationship with) and creating open communicative spaces to explore human connections. These processes were interdependent. Expanding the staff participants’ knowing-of-self was through their reflections and conversations with others on their responses to human connections while at work. Staff participants described this as a change in mindset towards being more human that seemed to reflect a change in focus towards how they feel and respond relationally. One participant described this as a, ‘kind of mindfulness’ (Occupational Therapist, Discussion Group) and another as, ‘letting your guard down’ (Therapy assistant, Discussion Group). Staff described personal challenges with sensitising to their relational aspects of work, one described themselves as, ‘not touchy feely’ (Physiotherapist, Observation notes), another said, ‘I’m not good at the more subjective side of care, I see myself as a ‘black and white’ evidence-based therapist.’ (Physiotherapist, Observation notes). The following quote, from a recently qualified occupational therapist, was from a reflection on a conversation she had with a patient’s family,

‘Before the family meeting I wrote out a long essay about what I was going to say, but I didn’t use it. Once I was in there it wasn’t right – I was aware of the power element and I needed to give them the same control, sometimes being in uniform doesn’t help. I’m human at the end of the day. It’s just being human and friendly. Because I am less experienced I like structure, but that meeting wasn’t structured. I need to learn to trust myself’ (Occupational Therapist, Observation notes). This quote illustrates how the therapist had carefully planned what she was going to say but then, through being sensitive to the relational dynamics within the meeting, and drawing on what it feels like within that specific context, changed her orientation from an information-giving stance towards a humanly relational one.

Increasing sensitivity towards human connections started with creating open communicative spaces. This involved being aware of different perspectives and not assuming understanding of others, along with openness to what may unfold in relation with others or, more simply, openness to connect with others. A few staff participants demonstrated their awareness of language of openness and curiosity to support this, illustrated in the following quote from a doctor talking about his conversation with a patient observed on a ward round,

‘It is learning the right questions, allowing somebody to talk, and from experience, knowing what the indications are from that particular story. And having those pauses, and, reinforcement, and just really trying to explore….’ (Doctor, Interview).

For others, an open communicative space developed new ways of understanding of others who may not have similar language or means of expressing their relationships,

‘We were talking about that (openness) in our team and there are just certain people in our team who just are not responsive to that. And you can’t change them, that’s their character, you can’t change them. I think it’s not that we’re more caring, it’s just a different way of …expressing things about patients’ (Therapy assistant, Discussion group).

Throughout the study, being purposefully and actively appreciative was a powerful approach to create safe open communicative spaces for discovering new perspectives and supporting participants’ openness. This openly appreciative stance underpinned the second process enabling human connections – valuing (Fig. 1).

Valuing

Being appreciative opened up new possibilities in relational activity. Noticing what was affirmative and appreciative, and talking with others about meaningful relational experiences, not only supported a new emergent narrative that valued relationships: it was also a form of relational practice itself. It heightened others’ awareness of the meaning ascribed to their habitual practices by patients, relatives or colleagues. It enabled staff to reconsider what was taken for granted and led to them forming different perspectives and collaborating to change the way they saw relationships on the stroke units. This is illustrated in the following two quotes where staff reflected on their appreciative noticing during the study,

‘It’s all about looking at the good things that we all do, whether it is something really small or something that’s really big. But even the littlest things to us, are a huge thing to other people’ (Healthcare assistant, Interview).

‘For the first time, you (the researcher) were coming in and saying, ‘we want to look at the good things’, and it’s rubbed off onto and what is the patient good at doing by us praising them. So saying to them, ‘oh that’s really good you worked really hard on that’ and members of staff saying it to other members of staff’ (Therapy assistant, Discussion group).

Using an overtly appreciative stance alongside a lifeworld-led approach enabled participants to increase sensitivity and value towards the lived bodily (embodied) experience of human connections that were beyond what words could describe, for example, ‘I felt I had a connection with her, I was willing her on to do well’ (Speech Therapist, Observation Notes), in another example, a physiotherapist described one of her meaningful relationships as, ‘It’s hard to describe, it felt like a different relationship’ (Physiotherapist, Discussion group). Noticing and valuing the lived bodily experience of being-in-relationships enhanced staff participants’ experiential knowing. This was shared with others predominately through story-telling that ‘unfurled’ the relational processes beyond the individual to the wider stroke unit team. This process is explored next.

Sharing, reflecting and energising

Sharing stories of meaningful experiences often led to reflections on new relational perspectives, illustrated in this reflection,

‘Hearing or reading about other people’s experiences since the project, one of the ones that interest me was Connie (a healthcare assistant) and her little touch of putting bed socks on a deceased patient after she had laid them out, and I saw her in, quite a different light. Because the way I see her, was seeing Connie as she means well but she’s quite immature and always says the wrong things, and I sometimes I want to step in and help her. But reading that, she does do the right things, at the right time for the right people’ (Therapy assistant, Discussion group).

Sharing in-the-moment appeared to be a particularly powerful opportunity for those developing their sensitivity towards their experiential knowing, as the feeling of the encounter appeared to be easier to recall and reflect on if carried out soon after the experience. For example, the researcher fed back to a nurse immediately after they observed her with a relative. The researcher had observed that she appeared relaxed and conversational with the relative. The researcher was interested to understand how she knew it was appropriate to put her arm around the relative. She responded with,

‘Well I’m a huggy person. I feel it in here (pointing to her chest) if it is alright. I know her too. I also know what it feels like with my dad when he is in hospital and I am the relative. It’s important for them to know that we care for them too’ (Nurse, Observation notes).

These types of reflective conversations made explicit the value of emotional and embodied responses to relationships. Even if the member of staff was not involved in the original encounter, some staff participants described how they had an emotional or embodied response to hearing or sharing a story. For example, one nurse, who was also a co-facilitator, shared with me,

‘Oh I’ve got some stories for you. Mrs. Smith’s family, she died last week. They asked me to thank Peter (a junior doctor). Peter had talked through the end-of-life pathway with them and they just wanted him to know that he was really lovely. When I told Peter, he said that he really appreciated that, it meant even more when it is about a patient dying, because you really want to get that right. I felt proud telling him. Proud that he did it’ (Nurse, Observation notes).

For others who found relational engagement with others less spontaneous, there appeared to be a moment when the study ‘clicked’ for them. This was a realisation that noticing and engaging with their response to being-in-relation could support their relational practice and led to feeling energised to co-create more human connections. It was engaging in the process of noticing, valuing and affirming relationships within the stroke units that enabled this realisation to occur. The following two quotations are examples from two members of staff when the study appeared to ‘click’ for them,

‘You feel choked up when you are writing them (her meaningful experiences). You remember the way the patient reacts, and their emotions. You realise that even though you are just doing your job, how important you are to them. When they said, ‘thank you’ I kind of just brushed it off, but I realise now that is really important to them. You kind of just take it for granted’ (Healthcare assistant, Observation notes).

‘No, I can see the value – if being a bit more human helps us to feel better about what we do’ (Physiotherapist, Discussion group).

Feeling energised to create more human connections within the stroke unit space led to the final relational process – freedom to act and be more relational.

Freedom to act/be more relational

Overall, increasing staff awareness of their relational self, and sensitising to meaningful human connections, supported a change in the type of discourse on the stroke units. A more relational, or relationship-centred, discourse was increasingly dispersed among the previously more dominant clinical and operational discourse of usual stroke unit care. This subtle, yet significant, change in discourse led to staff being more attuned towards relationships and, through talking about relationships more, increased the value of relationships within the team. A consequence of this was staff having more freedom to be relational and respond relationally in their daily practice. There were many examples from the data, for example: a housekeeper stopping mopping the floor to sit with a patient who was crying; a patient’s relative buying a birthday present for a neighbouring patient who had no family. One relative described how staff demonstrated their freedom to act more relationally with her husband who had dementia, saying,

‘It’s not just because they run to get him something when he asks, it’s just they kind of look at him and smile, treat him normally, sort of treat him like a human being’ (Relative, Interview).

Freedom to act didn’t necessarily have an observable change in what the staff did; however, it could change the perspective of the encounter and how staff felt towards the patient or relative which supported feelings of human connection. This is illustrated in a physiotherapist’s final reflections on participating in the study,

‘What has changed? It is how you are, not what you do. I need to ignore the pressure to do something and think about how you are. I have more awareness of positivity in developing relationships. I think outside the professional box’ (Physiotherapist, Personal reflective notes).

Staff participants emphasised the need for the processes towards relational knowing presented in Fig. 1 to be emergent and flexible. They described the process as different to other practice developments and to resist formalising the process into a framework that could potentially be seen by colleagues as a ‘tick-box exercise’. This feedback reflected the fluid and constantly changing nature of human connections and being-in-relation with others.

Discussion

This study describes how the experience of human connections are important within day-to-day life on two stroke units. This study demonstrates that patients, relatives and staff co-create both meaningful relationships and transient moments of human connections within the stroke unit space. We found that the experience of human connections was the foundation for meaningful relationships. When staff became aware of their human experience of connecting with others through the relational processes illustrated in Fig. 1, they recognised a change in themselves which, together with others, enabled and energised a wider change in the stroke unit culture. It was important to recognise that they didn’t have to learn any new techniques, they enhanced their awareness and gained new perspectives of the reality already existing around them. This allowed them to see new opportunities to connect more often with others. Increasing the value of human connections by colleagues created a supportive ward culture which enabled them the freedom to act and develop their relational practice. Therefore, we found that it is possible to increase the value of relational practice in stroke units within the current clinical context where biomedical and organisational processes tend to have priority.

The orientations of humanising relational practice have been described in previous research into relationship-centred care and relational practice within various care contexts including stroke units, (Bennett, Reference Bennett2016; Dewar & Nolan, Reference Dewar and Nolan2013; Dewar & Sharp, Reference Dewar and Sharp2013; Dickson, Riddell, Gilmour & McCormack, Reference Dickson, Riddell, Gilmour and McCormack2017; Feo et al., Reference Feo, Conroy, Marshall, Rasmussen, Wiechula and Kitson2017; McCormack, Karlsson, Dewing & Lerdal, Reference McCormack, Karlsson, Dewing and Lerdal2010). The processes described in this study align closely with Dewar’s 7C’s Caring Conversations Framework (Dewar & Nolan, Reference Dewar and Nolan2013) which outlines key attributes in interactions to support relationship-centred care. Our study describes new understandings in developing a humanising relationship-centred approach, specifically within the stroke unit MDT context. In particular, our study provides new understandings for practice around: (i) understanding of relational self; (ii) reflections enhancing embodied relational knowing, and; (iii) freedom to act. These are discussed in more detail below.

Self-awareness is often cited as being a pre-requisite, or even a competency, of person- or relationship-centred practice (Hughes, Bamford & May, Reference Hughes, Bamford and May2008; McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, Karlsson, Dewing and Lerdal2010; Scholl, Zill, Härter & Dirmaier, Reference Scholl, Zill, Härter and Dirmaier2014; Soklaridis et al., Reference Soklaridis, Ravitz, Adler Nevo and Lieff2016). Evidence in clinical practice on how to support practitioners’ self-awareness appears to have developed from an individualist perspective that stresses the practitioner’s responsibility in creating therapeutic relationships (Kitson, Dow, Calabrese, Locock & Muntlin Athlin, Reference Kitson, Dow, Calabrese, Locock and Muntlin Athlin2013; McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, Karlsson, Dewing and Lerdal2010; Tresolini & The Pew-Fetzer Task Force, Reference Tresolini1994). More recently, constructionist perspectives have highlighted the value of reflexive dialogues and reflective learning with others to support knowing of a shared and co-constructed meaning of self-in-relation (Dewar & Cook, Reference Dewar and Cook2014; Roddy & Dewar, Reference Roddy and Dewar2016; Wasserman & McNamee, Reference Wasserman and McNamee2010). We found in our study that there was a shift in attention in the relational encounter from organisational agendas or expected role behaviours towards enhancing human connections. All involved could draw on their personal human experience that brought mutuality to relationships which reflects what both Gergen (Reference Gergen2009) and McNamee and Hosking (Reference McNamee and Hosking2012) have described, that once relational processes rather than individuals are centred, it opens up possibilities toward the re-thinking of self within the context of relationships. For most participants, knowing of self-in-relation, and affirming and valuing human connections with others, was a transformative moment that resulted in feelings of well-being and increased their capacity to support further meaningful relationships.

We found that creating space to share stories focussing on relationality and the values and beliefs around one another’s lived experience on the stroke unit, enhanced the team’s collective ability to co-create new relationships based on those values or beliefs (Barrett & Fry, Reference Barrett and Fry2005; Cooperrider et al., Reference Cooperrider, Whitney and Stavros2005). This particular study showed how embodied, or felt-sense, is an important aspect of relational practice that is not explicitly conceptualised in the literature on person-, patient- or relationship-centredness, nor in qualitative studies into relationships in stroke unit settings. In our study, participants often experienced human connections as a feeling that was more difficult to put into words. We found that humanising lifeworld-led theory informed exploring the feeling of human connectedness with participants and, through the humanising values framework (Dahlberg et al., Reference Dahlberg, Todres and Galvin2009), provided a discourse for participants’ own embodied (felt-sense) knowing. Galvin and Todres (Reference Galvin and Todres2011) have described this as ‘embodied relational understanding’. A humanising lifeworld-led lens supported sensitivity beyond practitioners’ cognitive understanding of what is needed for a positive and therapeutic relationship and increased embodied relational understanding of being-in-relation with others. Embodied knowing in the context of humanising lifeworld-led care theories has been described within a small number of phenomenological studies into stroke care and rehabilitation (Hydén & Antelius, Reference Hydén and Antelius2011; Nyström, Reference Nyström2006; Nyström, Reference Nyström2009; Suddick, Cross, Vuoskoski, Stew & Galvin, Reference Suddick, Cross, Vuoskoski, Stew and Galvin2019; Sundin & Jansson, Reference Sundin and Jansson2003; Sundin, Jansson & Norberg, Reference Sundin, Jansson and Norberg2002), with the majority of these studies working with people with communication disability to explore non-verbal understandings in healthcare relationships. However, only two other known studies have researched the practical translation of embodied relational knowing using action research methods to inform stroke unit relationships (Dewar & Nolan, Reference Dewar and Nolan2013; Galvin et al., Reference Galvin, Pound, Cowdell, Ellis-Hill, Sloan, Brooks and Ersser2020), and our study contributes further evidence to this emerging area.

Staff participants’ freedom to respond relationally was founded on their recognition that relational practice was a way-of-being, an intention to humanly connect, rather than their observable behaviour. Having the freedom to be relational was grounded in knowing their relational self, and having confidence in the possibilities of new ways of being-in-the-moment with others – it did not require a set of competencies, skills or specific knowledge because, by the nature of being human, they already had human understanding. Others have similarly described relational understanding as constantly changing and ongoing in practice situations, and mixed with not knowing, or the unknown (Ellis-Hill, Pound & Galvin, Reference Ellis-Hill, Pound and Galvin2021; Todres, Reference Todres2008). Freedom to respond relationally required staff participants to navigate the prevailing positivist biomedical culture and clinical discourse while equally valuing theirs and others lived experience of their relationships. Tensions between organisational and personal aims in healthcare are well known (Coghlan & Casey, Reference Coghlan and Casey2001; Hebblethwaite, Reference Hebblethwaite2013; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Harrison, Gardiner and Jones2017). An important aspect of our study was the concurrent individual and team-level approach that enabled staff to develop and practise their new ways of being relational. Embodied relational knowing was particularly valuable to remain connected with our common humanity during the study. It added vitality, a deep sense of meaning and a motivating force to prevent ‘going through the motions’ in healthcare relationships and practice development. Through this relational process, we have shown that patients, relatives and staff well-being can improve when they had the freedom to respond to others through meaningful relationships.

Conclusion

It is important when considering the quality of relationships formed on stroke units that practitioners are supported in developing and maintaining their sensitivity towards how relationships are co-created among patients, relatives/carers and colleagues. This sensitivity is subject to team and organisational cultures and appears to be easily obscured when biomedical and organisational needs are prioritised which is increasingly described in more recent qualitative studies on in-patient stroke units. Creating opportunities for staff to reflect on their human and lived experience of relationships within the stroke unit space required active facilitation. Space for reflection enabled participants to see their own relationships and themselves (knowing-self) in relation to their work. The process of developing relational knowing and practice was achieved with a nuanced and improvisatory manner through story-telling and reflections that supported multiplicity and reflected the uniqueness of being-in-relation. With each conversation, there were possibilities for new knowing and experimentation of new relational practices that maintained a local-contextual relevance and aliveness. Humanising relational knowing was not supported through procedures, guidelines, training or competencies. An alternative approach that is constantly changing, alive and in relation with others is imperative to nurture and sustain relational practice.

Financial support

This work was supported by Health Education England (HEE) / National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (CG, award number CDRF-2014-05-017). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, NHS or the UK Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflicts of interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.