1. Introduction

Subglacial water flow is regulated by the effective pressure, the difference between the ice and water pressures at the glacier base (Röthlisberger, Reference Röthlisberger1972; Shreve, Reference Shreve1972). The effective pressure controls rates of creep closure in subglacial drainage elements such as channels and cavities, and thereby influences the volumetric discharge by restricting water flow (Nye, Reference Nye1976; Flowers, Reference Flowers2015). Likewise, the magnitude and direction of water flow are determined by hydraulic potential gradients, which depend on gradients in the effective pressure (Hewitt, Reference Hewitt2011). The effective pressure also influences the frictional behaviour at the ice–bed interface and modulates ice–flow speeds (Lliboutry, Reference Lliboutry1968; Bindschadler, Reference Bindschadler1983; Schoof, Reference Schoof2005; Zoet and Iverson, Reference Zoet and Iverson2020). While the effective pressure is a fundamental variable that controls subglacial water flow and sliding at the ice–bed interface, direct measurements obtained via borehole drilling are sparse (Iken and others, Reference Iken, Echelmeyer, Harrison and Funk1993; Fountain, Reference Fountain1994; Hubbard and others, Reference Hubbard, Sharp, Willis, Nielsen and Smart1995; Engelhardt and Kamb, Reference Engelhardt and Kamb1997; Meierbachtol and others, Reference Meierbachtol, Harper and Humphrey2013; Andrews and others, Reference Andrews2014; Rada and Schoof, Reference Rada and Schoof2018).

Subglacial lakes that are observed to episodically fill and drain, often called ‘active’ lakes, present an opportunity for constraining effective pressures with altimetry data because subglacial water-volume changes manifest at the ice-sheet surface as elevation-change anomalies (Fricker and others, Reference Fricker, Scambos, Bindschadler and Padman2007; Reference Fricker, Scambos, Carter, Davis, Haran and Joughin2010; Fricker and Scambos, Reference Fricker and Scambos2009; Smith and others, Reference Smith, Fricker, Joughin and Tulaczyk2009). In particular, the coupling between the effective pressure in a subglacial lake with the surrounding drainage system drives the water-volume oscillations that are expressed at the ice-sheet surface (Evatt and others, Reference Evatt, Fowler, Clark and Hulton2006; Fowler, Reference Fowler2009; Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Creyts, Kingslake and Spiegelman2019). The ICESat (2003–09) and CryoSat-2 (2010 to present) satellite altimetry missions have detected over one hundred active lakes beneath the Antarctic Ice Sheet, while a smaller number have been found in Greenland, Iceland and various mountain glaciers (Smith and others, Reference Smith, Fricker, Joughin and Tulaczyk2009; Wright and Siegert, Reference Wright and Siegert2012; Siegfried and Fricker, Reference Siegfried and Fricker2018; Livingstone and others, Reference Livingstone2022). NASA’s ICESat-2 satellite altimetry mission (2018 to present) has allowed for continued detection and monitoring of active subglacial lakes at high spatial and temporal resolution (Neckel and others, Reference Neckel, Franke, Helm, Drews and Jansen2021; Siegfried and Fricker, Reference Siegfried and Fricker2021; Livingstone and others, Reference Livingstone2022; Fan and others, Reference Fan, Ke, Shen, Xiao, Livingstone and Sole2023; Freer and others, Reference Freer2024; Gray and others, Reference Gray2024a; Reference Gray2024b).

Previous modelling work quantified subglacial lake effective pressures with a finite element method (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Spiegelman and Creyts2021b). A limitation of the finite element method is that the mean effective pressure in the lake is determined numerically with a Lagrange multiplier, which only furnishes an indirect relation between lake activity and viscous ice flow. An alternative approach was developed to estimate subglacial water-volume changes with an inverse method that accounts for the effects of viscous ice flow on surface-elevation changes (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). The inverse method assumes that subglacial lake oscillations represent small perturbations to an ice-flow state that is described by auxiliary parameters such as the ice thickness, viscosity, flow speed and basal sliding coefficient (cf. Gudmundsson, Reference Gudmundsson2003).

In this study, we develop a method for estimating effective pressures from elevation-change anomalies above active subglacial lakes by synthesising the previous modelling approaches (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Spiegelman and Creyts2021b; Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). First, we derive general expressions for the effective pressure that depend on the ice–surface elevation and viscous ice flow. Then, we relate the effective pressure to the elevation change and basal vertical velocity with a linearised model (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). We present semi-analytical and synthetic examples to illustrate the basic behaviour of the method. Finally, we apply the method to a collection of subglacial lakes in Antarctica that have shown activity during the ICESat-2 era.

2. Model derivation

In this section, we first derive general formulas for the effective pressure, which is defined by

where ![]() $p_\mathrm{i}$ is the ice pressure and

$p_\mathrm{i}$ is the ice pressure and ![]() $p_\mathrm{w}$ is the water pressure. We refer to the condition

$p_\mathrm{w}$ is the water pressure. We refer to the condition ![]() $N=0$—when the ice and water pressures are balanced—as ‘flotation’. Then, we use a linearised (small perturbation) model to relate the effective pressure in a subglacial lake to the basal vertical velocity anomaly

$N=0$—when the ice and water pressures are balanced—as ‘flotation’. Then, we use a linearised (small perturbation) model to relate the effective pressure in a subglacial lake to the basal vertical velocity anomaly ![]() $w_\mathrm{b}$ that produces the observed surface-elevation change

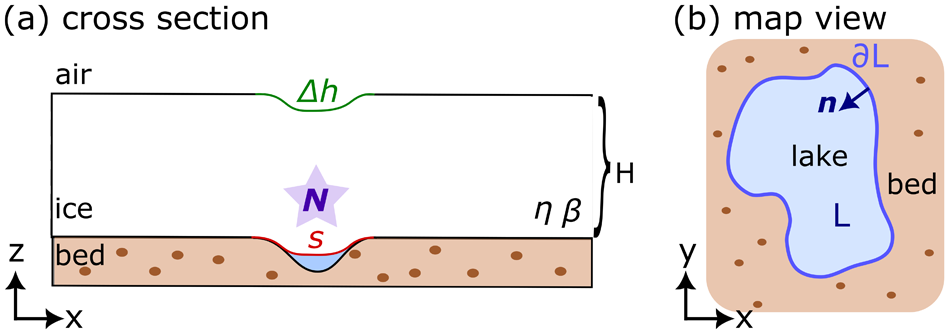

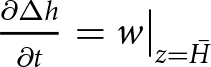

$w_\mathrm{b}$ that produces the observed surface-elevation change ![]() $\Delta h$ (Figs. 1,2).

$\Delta h$ (Figs. 1,2).

Figure 1. (a) Sketch of a subglacial lake in cross-section highlighting the elevation-change anomaly ![]() $\Delta h$, ice-base elevation

$\Delta h$, ice-base elevation ![]() $s$, and effective pressure

$s$, and effective pressure ![]() $N$. The ice layer over the lake is characterised by the thickness

$N$. The ice layer over the lake is characterised by the thickness ![]() $H$ and viscosity

$H$ and viscosity ![]() $\eta$, while the ice-bed interface is characterised by the basal drag coefficient

$\eta$, while the ice-bed interface is characterised by the basal drag coefficient ![]() $\beta$. (b) Map-view sketch showing the lake area

$\beta$. (b) Map-view sketch showing the lake area ![]() $L$, lake boundary

$L$, lake boundary ![]() $\partial L$ and normal vector

$\partial L$ and normal vector ![]() $\pmb{n}$.

$\pmb{n}$.

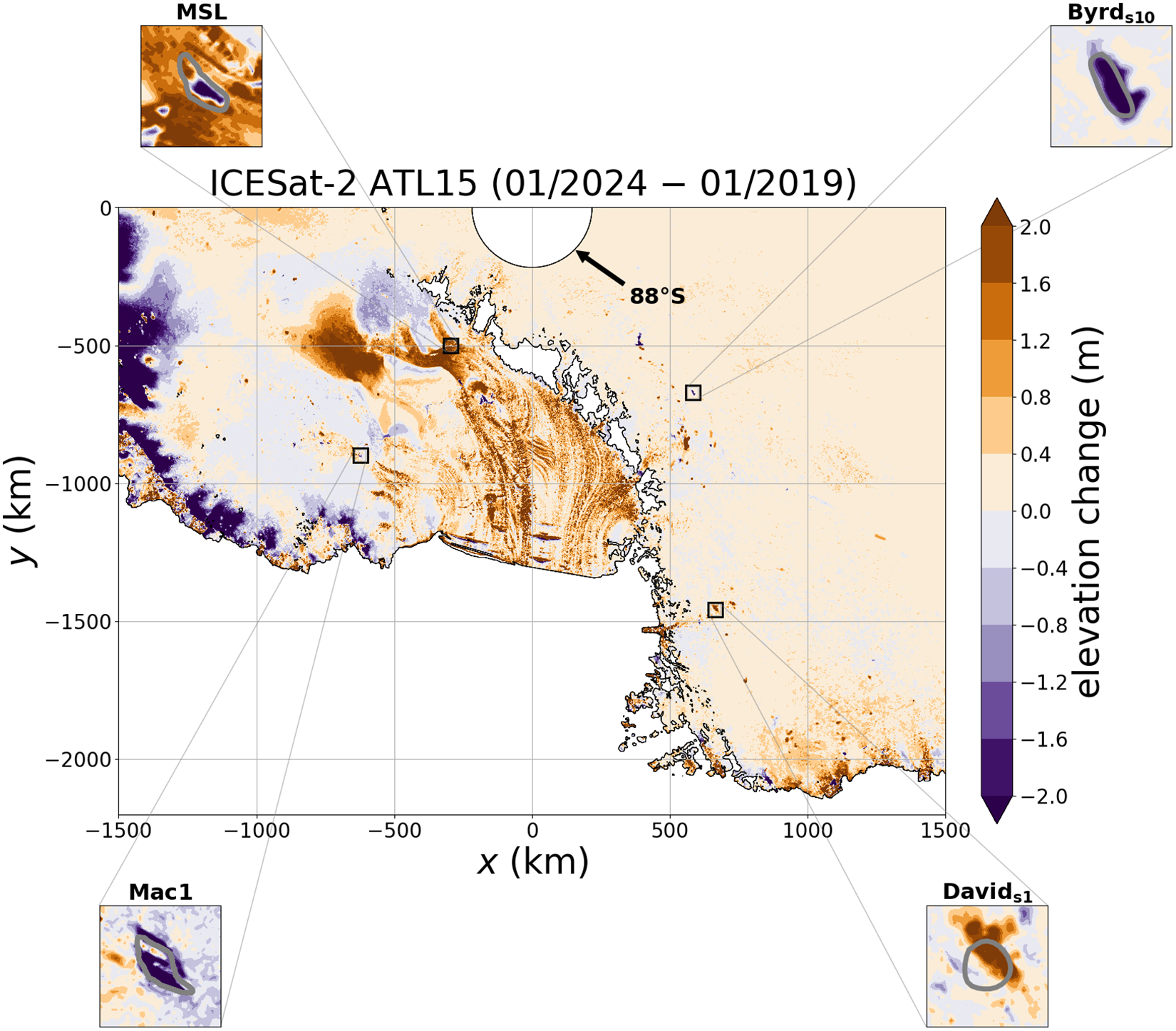

Figure 2. Map of ICESat-2 elevation-change data from Antarctica (ATL15 gridded product; Smith and others, Reference Smith, Jelley, Dickinson, Sutterley, Neumann and Harbeck2024) with insets showing anomalies over subglacial lakes Mac1 (MacAyeal Ice Stream), Mercer Subglacial Lake (MSL; Mercer Ice Stream), Byrds10 (Byrd Glacier) and Davids1 (David Glacier). The map-plane ![]() $(x, y)$ coordinates in the ATL15 dataset correspond to the Antarctic Polar Stereographic Projection (EPSG:3031). Lake outlines from Siegfried and Fricker (Reference Siegfried and Fricker2018) are shown in silver on the insets.

$(x, y)$ coordinates in the ATL15 dataset correspond to the Antarctic Polar Stereographic Projection (EPSG:3031). Lake outlines from Siegfried and Fricker (Reference Siegfried and Fricker2018) are shown in silver on the insets.

We represent the ice-surface elevation ![]() $z=h(x,y,t)$ via

$z=h(x,y,t)$ via ![]() $h= \bar{H} + \Delta h$ where

$h= \bar{H} + \Delta h$ where ![]() $\bar{H}$ is the background ice thickness and

$\bar{H}$ is the background ice thickness and ![]() $\Delta h$ is the elevation-change anomaly over the lake (Fig. 1a). The lower surface of the ice is denoted by

$\Delta h$ is the elevation-change anomaly over the lake (Fig. 1a). The lower surface of the ice is denoted by ![]() $z=s(x,y,t)$. We assume that ice deforms as a viscous fluid according to the incompressible Stokes equations with a linear sliding law at the base and a stress-free condition at the ice-air interface (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). For consistency with the linearised framework, we assume a uniform ice viscosity

$z=s(x,y,t)$. We assume that ice deforms as a viscous fluid according to the incompressible Stokes equations with a linear sliding law at the base and a stress-free condition at the ice-air interface (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). For consistency with the linearised framework, we assume a uniform ice viscosity ![]() ${\eta}$, basal drag coefficient

${\eta}$, basal drag coefficient ![]() ${\beta}$ and ice thickness

${\beta}$ and ice thickness ![]() $\bar{H}$ in the vicinity of the lake. The assumptions of a linearised framework and uniform material properties are adopted because subglacial lakes are expected to only generate small changes in ice flow relative to a given background state (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). The primary limitation of this approach is that the basal drag coefficient does not depend on the time-varying effective pressure in the subglacial lake, but is instead assumed to be constant. The relevant components of the linearised model are summarised below while precise details on the derivation are outlined in Appendix A.

$\bar{H}$ in the vicinity of the lake. The assumptions of a linearised framework and uniform material properties are adopted because subglacial lakes are expected to only generate small changes in ice flow relative to a given background state (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). The primary limitation of this approach is that the basal drag coefficient does not depend on the time-varying effective pressure in the subglacial lake, but is instead assumed to be constant. The relevant components of the linearised model are summarised below while precise details on the derivation are outlined in Appendix A.

2.1. Effective pressure formulas

2.1.1. Hydrostatic approximation

We derive an expression for the effective pressure in a subglacial lake by assuming that the water pressure follows a hydrostatic gradient,

where ![]() $\rho_\mathrm{w}=1000$ kg m

$\rho_\mathrm{w}=1000$ kg m![]() $^{-3}$ is the density of water and

$^{-3}$ is the density of water and ![]() $\pmb{g} = -g[0,0,1]^\mathrm{T}$ is gravitational acceleration with magnitude

$\pmb{g} = -g[0,0,1]^\mathrm{T}$ is gravitational acceleration with magnitude ![]() $g=9.81$ m s

$g=9.81$ m s![]() $^{-2}$. The water pressure is not known a priori because it depends on the stresses in the overlying ice column (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Spiegelman and Creyts2021b). Therefore, the water pressure is determined up to a constant that depends only on the map-plane coordinates

$^{-2}$. The water pressure is not known a priori because it depends on the stresses in the overlying ice column (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Spiegelman and Creyts2021b). Therefore, the water pressure is determined up to a constant that depends only on the map-plane coordinates ![]() $(x,y)$, which we resolve by averaging over the surface area of the lake. In this way, we obtain a formula for the water pressure at the ice–water interface (

$(x,y)$, which we resolve by averaging over the surface area of the lake. In this way, we obtain a formula for the water pressure at the ice–water interface (![]() $z=s$),

$z=s$),

where bars denote spatial means over the surface area of the lake (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Spiegelman and Creyts2021b). Taking the difference of the ice pressure ![]() $p_\mathrm{i}$ with (3), we obtain an expression for the effective pressure

$p_\mathrm{i}$ with (3), we obtain an expression for the effective pressure ![]() $N$ over the subglacial lake,

$N$ over the subglacial lake,

where we have defined the density difference, ![]() $\Delta \rho=\rho_\mathrm{w}-\rho_\mathrm{i}$, and the difference between the ice pressure and cryostatic pressure,

$\Delta \rho=\rho_\mathrm{w}-\rho_\mathrm{i}$, and the difference between the ice pressure and cryostatic pressure, ![]() $\varepsilon$. Two challenges arise in applying the formula (4) to estimate effective pressures in subglacial lakes. First, the mean effective pressure (

$\varepsilon$. Two challenges arise in applying the formula (4) to estimate effective pressures in subglacial lakes. First, the mean effective pressure (![]() $\bar{N}$) and the deviation of the ice pressure from the cryostatic pressure (

$\bar{N}$) and the deviation of the ice pressure from the cryostatic pressure (![]() $\varepsilon$) are undetermined at this stage, requiring incorporation of the ice-flow dynamics (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Spiegelman and Creyts2021b). Second, the motion of the ice–water interface

$\varepsilon$) are undetermined at this stage, requiring incorporation of the ice-flow dynamics (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Spiegelman and Creyts2021b). Second, the motion of the ice–water interface ![]() $s$ does not necessarily correspond to the motion of the ice surface

$s$ does not necessarily correspond to the motion of the ice surface ![]() $h$ (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Creyts, Kingslake, Siegfried and Spiegelman2021a; Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). We resolve these challenges by directly incorporating the effects of ice flow into the method below.

$h$ (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Creyts, Kingslake, Siegfried and Spiegelman2021a; Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). We resolve these challenges by directly incorporating the effects of ice flow into the method below.

The hydrostatic assumption implies that subglacial lakes are still bodies of water that tend to capture water from surrounding areas. Gradients in the subglacial lake effective pressure (4) balance the ‘background’ hydraulic gradient of the subglacial drainage system in the limit of a cryostatic ice pressure,

\begin{equation}

\nabla N\big|_{\varepsilon=0} = \rho_\mathrm{i} g \nabla h + \Delta\rho\, g \nabla s,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\nabla N\big|_{\varepsilon=0} = \rho_\mathrm{i} g \nabla h + \Delta\rho\, g \nabla s,

\end{equation} which implies that the water flux is zero and that the lake corresponds to a minima in the hydraulic potential (e.g.,

Hewitt, Reference Hewitt2011). In subglacial drainage systems, water flows due to deviations from the background hydraulic gradient, so we cannot estimate effective pressures with the formula (4) outside of the lake boundary. Therefore, we will restrict formulas to the interior of the lake below by introducing an indicator function ![]() $\chi$, defined by

$\chi$, defined by

\begin{equation}

\chi = \begin{cases}

1 & \pmb{x} \in L \\ 0 & \pmb{x} \notin L

\end{cases},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\chi = \begin{cases}

1 & \pmb{x} \in L \\ 0 & \pmb{x} \notin L

\end{cases},

\end{equation} where ![]() $L$ denotes the lake area (Fig. 1). While subglacial lake shorelines can migrate during volume-change events, we assume a fixed lake boundary

$L$ denotes the lake area (Fig. 1). While subglacial lake shorelines can migrate during volume-change events, we assume a fixed lake boundary ![]() $L$ for simplicity (Siegfried and Fricker, Reference Siegfried and Fricker2021; Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Creyts, Kingslake, Siegfried and Spiegelman2021a; Reference Stubblefield, Spiegelman and Creyts2021b). We revisit this assumption in the discussion. Extending the current implementation to allow for time-varying boundaries (evolving

$L$ for simplicity (Siegfried and Fricker, Reference Siegfried and Fricker2021; Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Creyts, Kingslake, Siegfried and Spiegelman2021a; Reference Stubblefield, Spiegelman and Creyts2021b). We revisit this assumption in the discussion. Extending the current implementation to allow for time-varying boundaries (evolving ![]() $\chi$) would be straightforward (see Data Availability statement for code repository).

$\chi$) would be straightforward (see Data Availability statement for code repository).

2.1.2. Small-slope approximation

We derive a direct relation between the effective pressure and ice dynamics by considering the normal stress at the ice-water interface. Assuming that the slope of the basal surface ![]() $s$ is small over the subglacial lake, the normal stress

$s$ is small over the subglacial lake, the normal stress ![]() $\sigma_\mathrm{n}$ at the base

$\sigma_\mathrm{n}$ at the base ![]() $z=s(x,y,t)$ is given by

$z=s(x,y,t)$ is given by

\begin{equation}

\sigma_\mathrm{n} = p_\mathrm{i} - 2\eta\frac{\partial w}{\partial z},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\sigma_\mathrm{n} = p_\mathrm{i} - 2\eta\frac{\partial w}{\partial z},

\end{equation} where ![]() $w$ is the vertical component of the ice velocity (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Wearing and Meyer2023b). The normal stress equals the water pressure at the ice-water boundary, which implies that the effective pressure is given by

$w$ is the vertical component of the ice velocity (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Wearing and Meyer2023b). The normal stress equals the water pressure at the ice-water boundary, which implies that the effective pressure is given by

\begin{equation}

N = 2{\eta} \frac{\partial w}{\partial z}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

N = 2{\eta} \frac{\partial w}{\partial z}

\end{equation} at ![]() $z = s(x,y,t)$. Incompressibility leads to an expression in terms of the horizontal flow divergence,

$z = s(x,y,t)$. Incompressibility leads to an expression in terms of the horizontal flow divergence,

\begin{equation}

N = -2{\eta} \left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial v}{\partial y}\right),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

N = -2{\eta} \left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial v}{\partial y}\right),

\end{equation} where ![]() $\pmb{u}=[u,v]^\mathrm{T}$ is the horizontal velocity. Eqn. (10) shows that the effective pressure is controlled by viscous flow towards the lake, reflecting the concept of creep closure. The ice is floating (

$\pmb{u}=[u,v]^\mathrm{T}$ is the horizontal velocity. Eqn. (10) shows that the effective pressure is controlled by viscous flow towards the lake, reflecting the concept of creep closure. The ice is floating (![]() $N\equiv 0$) when the horizontal flow divergence vanishes over the lake as in the case of rigid motion or cryostatic balance. An approximate analysis using (10) and mass continuity shows that the effective pressure is related to dynamic thickness changes through the logarithmic strain rate of the ice column (Appendix B). The effective pressure formulas (9)-(10) are general in the sense that they hold everywhere there is an ice–water interface with small slope. Below, we combine the effective pressure formula (9) that is based on viscous ice stresses with the hydrostatic formula (4) to estimate effective pressures in active subglacial lakes.

$N\equiv 0$) when the horizontal flow divergence vanishes over the lake as in the case of rigid motion or cryostatic balance. An approximate analysis using (10) and mass continuity shows that the effective pressure is related to dynamic thickness changes through the logarithmic strain rate of the ice column (Appendix B). The effective pressure formulas (9)-(10) are general in the sense that they hold everywhere there is an ice–water interface with small slope. Below, we combine the effective pressure formula (9) that is based on viscous ice stresses with the hydrostatic formula (4) to estimate effective pressures in active subglacial lakes.

We integrate Eqn. (10) over the lake area ![]() $L$ and use the divergence theorem to obtain an expression for the mean effective pressure,

$L$ and use the divergence theorem to obtain an expression for the mean effective pressure,

\begin{equation}

\bar{N} = \frac{2{\eta}}{|L|} \int_{\partial L} \pmb{u}\cdot \pmb{n}\;\mathrm{d}s,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\bar{N} = \frac{2{\eta}}{|L|} \int_{\partial L} \pmb{u}\cdot \pmb{n}\;\mathrm{d}s,

\end{equation} where ![]() $\partial L$ is the boundary of the lake,

$\partial L$ is the boundary of the lake, ![]() $|L|$ is the surface area of the lake, and

$|L|$ is the surface area of the lake, and ![]() $\pmb{n}$ denotes an inward-pointing unit normal to the lake boundary (Fig. 1b). In previous work, the mean effective pressure

$\pmb{n}$ denotes an inward-pointing unit normal to the lake boundary (Fig. 1b). In previous work, the mean effective pressure ![]() $\bar{N}$ was determined with a Lagrange multiplier, which provided an indirect relation between the effective pressure and ice flow (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Spiegelman and Creyts2021b). Eqn. (11) instead provides a direct relation between the mean effective pressure in a subglacial lake and viscous flow towards the lake.

$\bar{N}$ was determined with a Lagrange multiplier, which provided an indirect relation between the effective pressure and ice flow (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Spiegelman and Creyts2021b). Eqn. (11) instead provides a direct relation between the mean effective pressure in a subglacial lake and viscous flow towards the lake.

As a simple example, Eqn. (11) implies that a lake with circular boundary has a mean effective pressure of ![]() $\bar{N}=4\eta \bar{u}_\mathrm{in} /r$ where

$\bar{N}=4\eta \bar{u}_\mathrm{in} /r$ where ![]() $r$ is the radius of the lake and

$r$ is the radius of the lake and ![]() $\bar{u}_\mathrm{in}$ is the average inflow speed. This simple expression shows the sensitivity of the mean effective pressure to the ice viscosity. In the limit of a large lake area (

$\bar{u}_\mathrm{in}$ is the average inflow speed. This simple expression shows the sensitivity of the mean effective pressure to the ice viscosity. In the limit of a large lake area (![]() $r\to\infty$), the mean effective pressure approaches zero analogous to a floating ice shelf (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Wearing and Meyer2023b). On the other hand, the mean effective pressure can become large in the limit of a small lake area (

$r\to\infty$), the mean effective pressure approaches zero analogous to a floating ice shelf (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Wearing and Meyer2023b). On the other hand, the mean effective pressure can become large in the limit of a small lake area (![]() $r\to 0$), although the inflow speed

$r\to 0$), although the inflow speed ![]() $\bar{u}_\mathrm{in}$ may also diminish in this limit. While lakes that are smaller than the ice thickness are difficult to detect with altimetry-based methods (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Creyts, Kingslake, Siegfried and Spiegelman2021a), many small lakes that could have elevated effective pressures have been detected with ice-penetrating radar (Wright and Siegert, Reference Wright and Siegert2012; MacKie and others, Reference MacKie, Schroeder, Caers, Siegfried and Scheidt2020).

$\bar{u}_\mathrm{in}$ may also diminish in this limit. While lakes that are smaller than the ice thickness are difficult to detect with altimetry-based methods (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Creyts, Kingslake, Siegfried and Spiegelman2021a), many small lakes that could have elevated effective pressures have been detected with ice-penetrating radar (Wright and Siegert, Reference Wright and Siegert2012; MacKie and others, Reference MacKie, Schroeder, Caers, Siegfried and Scheidt2020).

2.2. Perturbation formulas

Next, we introduce a linearised (small perturbation) approach for estimating the effective pressure ![]() $N$ from elevation changes (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). We assume a uniform ice thickness

$N$ from elevation changes (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). We assume a uniform ice thickness ![]() $\bar{H}$ in the base state where the elevation of the ice-water interface

$\bar{H}$ in the base state where the elevation of the ice-water interface ![]() $s$ corresponds to

$s$ corresponds to ![]() $z=0$ (Fig. 1). The viscosity

$z=0$ (Fig. 1). The viscosity ![]() $\eta$ and basal drag

$\eta$ and basal drag ![]() ${\beta}$ are also assumed to be uniform in the vicinity of the lake. The limitations of these assumptions have been discussed and tested against a fully nonlinear model in previous work (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). Formally, we consider

${\beta}$ are also assumed to be uniform in the vicinity of the lake. The limitations of these assumptions have been discussed and tested against a fully nonlinear model in previous work (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). Formally, we consider ![]() $N$,

$N$, ![]() $w$,

$w$, ![]() $\Delta h$ and

$\Delta h$ and ![]() $s$ to be perturbations to a cryostatic base state characterised by the ice pressure

$s$ to be perturbations to a cryostatic base state characterised by the ice pressure ![]() $p_\mathrm{i} = \rho_\mathrm{i}g(\bar{H}-z)$ in addition to vanishing vertical velocity and effective pressure fields. In the base state, Eqn. (8) implies that the mean water pressure is cryostatic (

$p_\mathrm{i} = \rho_\mathrm{i}g(\bar{H}-z)$ in addition to vanishing vertical velocity and effective pressure fields. In the base state, Eqn. (8) implies that the mean water pressure is cryostatic (![]() $\bar{p}_\mathrm{w} = \rho_\mathrm{i}g\bar{H}$) while the mean effective pressure is zero (

$\bar{p}_\mathrm{w} = \rho_\mathrm{i}g\bar{H}$) while the mean effective pressure is zero (![]() $\bar{N}=0$). Likewise, the parameter

$\bar{N}=0$). Likewise, the parameter ![]() $\varepsilon$ vanishes in the cryostatic base state. We test the assumption that the background state is at flotation (

$\varepsilon$ vanishes in the cryostatic base state. We test the assumption that the background state is at flotation (![]() $N=0$) below by considering dynamic thickness changes away from the lake (Table 1; Appendix B).

$N=0$) below by considering dynamic thickness changes away from the lake (Table 1; Appendix B).

We linearise the effective pressure around the base-state lower-surface elevation (![]() $z=0$) via

$z=0$) via

\begin{equation}

N\big|_{z=s} = N\big|_{z=0} + N'(0,s)\big|_{\varepsilon=0},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

N\big|_{z=s} = N\big|_{z=0} + N'(0,s)\big|_{\varepsilon=0},

\end{equation} where the second term represents the directional derivative of ![]() $N$ at

$N$ at ![]() $z=0$ in the direction of the ice–water interface perturbation

$z=0$ in the direction of the ice–water interface perturbation ![]() $z=s$ in the cryostatic base state (

$z=s$ in the cryostatic base state (![]() $\varepsilon=0)$. We find from Eqn. (4) that the directional derivative is

$\varepsilon=0)$. We find from Eqn. (4) that the directional derivative is ![]() $g\Delta\rho\, (s-\bar{s})$. On the other hand, we resolve the first term in (12) with the expression (9) evaluated at

$g\Delta\rho\, (s-\bar{s})$. On the other hand, we resolve the first term in (12) with the expression (9) evaluated at ![]() $z=0$.

$z=0$.

With these considerations, the linearised expression (12) becomes

\begin{equation}

N\big|_{z=s} = 2\eta\frac{\partial w}{\partial z}\big|_{z=0} + g\Delta\rho\, (s-\bar{s})\chi.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

N\big|_{z=s} = 2\eta\frac{\partial w}{\partial z}\big|_{z=0} + g\Delta\rho\, (s-\bar{s})\chi.

\end{equation} The first term in (13) captures the effects of viscous ice flow while the second term represents perturbations to the hydrostatic normal stress due to movement of the ice base (cf.

Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Wearing and Meyer2023b). The second term (directional derivative) in (13) has been truncated with the indicator function ![]() $\chi$ because variations in the effective pressure cannot be constrained outside of the lake boundary with the hydrostatic formula. In particular, we recover the expression for the mean effective pressure (11) from Eqn. (13) because the mean of the hydrostatic term over the lake area vanishes.

$\chi$ because variations in the effective pressure cannot be constrained outside of the lake boundary with the hydrostatic formula. In particular, we recover the expression for the mean effective pressure (11) from Eqn. (13) because the mean of the hydrostatic term over the lake area vanishes.

We solve the linearised problem by deriving a formula for ![]() $\widehat{N}$, the Fourier transform of the effective pressure (13) with respect to the map-plane coordinates

$\widehat{N}$, the Fourier transform of the effective pressure (13) with respect to the map-plane coordinates ![]() $(x,y)$. In Appendix A, we show that

$(x,y)$. In Appendix A, we show that

\begin{equation}

\frac{\partial \widehat{w}}{\partial z}\big|_{z=0} = \tfrac{1}{\bar{H}}\mathsf{C}_w \widehat{w_\mathrm{b}}-\tfrac{\rho_\mathrm{i}g}{2\eta}\mathsf{C}_h \widehat{\Delta h} ,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\frac{\partial \widehat{w}}{\partial z}\big|_{z=0} = \tfrac{1}{\bar{H}}\mathsf{C}_w \widehat{w_\mathrm{b}}-\tfrac{\rho_\mathrm{i}g}{2\eta}\mathsf{C}_h \widehat{\Delta h} ,

\end{equation}where we have defined the functions

\begin{equation}

\mathsf{C}_h = \frac{2k^2 e^{k} \left(e^{2k} + 1 \right)}{\left(k+{\gamma}\right) e^{4

k} + 2\left({\gamma} + 2 ({1+\gamma}) k^{2} \right) e^{2 k} - \left(k-{\gamma}\right)}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mathsf{C}_h = \frac{2k^2 e^{k} \left(e^{2k} + 1 \right)}{\left(k+{\gamma}\right) e^{4

k} + 2\left({\gamma} + 2 ({1+\gamma}) k^{2} \right) e^{2 k} - \left(k-{\gamma}\right)}

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

\mathsf{C}_w = \frac{4k^4 e^{2k}}{\left(k+{\gamma}\right) e^{4

k} + 2\left({\gamma} + 2 ({1+\gamma}) k^{2} \right) e^{2 k} - \left(k-{\gamma}\right)},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mathsf{C}_w = \frac{4k^4 e^{2k}}{\left(k+{\gamma}\right) e^{4

k} + 2\left({\gamma} + 2 ({1+\gamma}) k^{2} \right) e^{2 k} - \left(k-{\gamma}\right)},

\end{equation} with ![]() $k$ being the wavevector magnitude normalised by the background ice thickness

$k$ being the wavevector magnitude normalised by the background ice thickness ![]() $\bar{H}$. In Eqns. (15)-(16), we have introduced a nondimensional parameter that arises from the sliding law,

$\bar{H}$. In Eqns. (15)-(16), we have introduced a nondimensional parameter that arises from the sliding law,

\begin{equation}

\gamma = \frac{\beta \bar{H}}{2\eta},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\gamma = \frac{\beta \bar{H}}{2\eta},

\end{equation} which relates all of the fundamental parameters that characterise the base state. The magnitudes of the functions ![]() $\mathsf{C}_h$ and

$\mathsf{C}_h$ and ![]() $\mathsf{C}_w$ decay at larger values of the sliding parameter

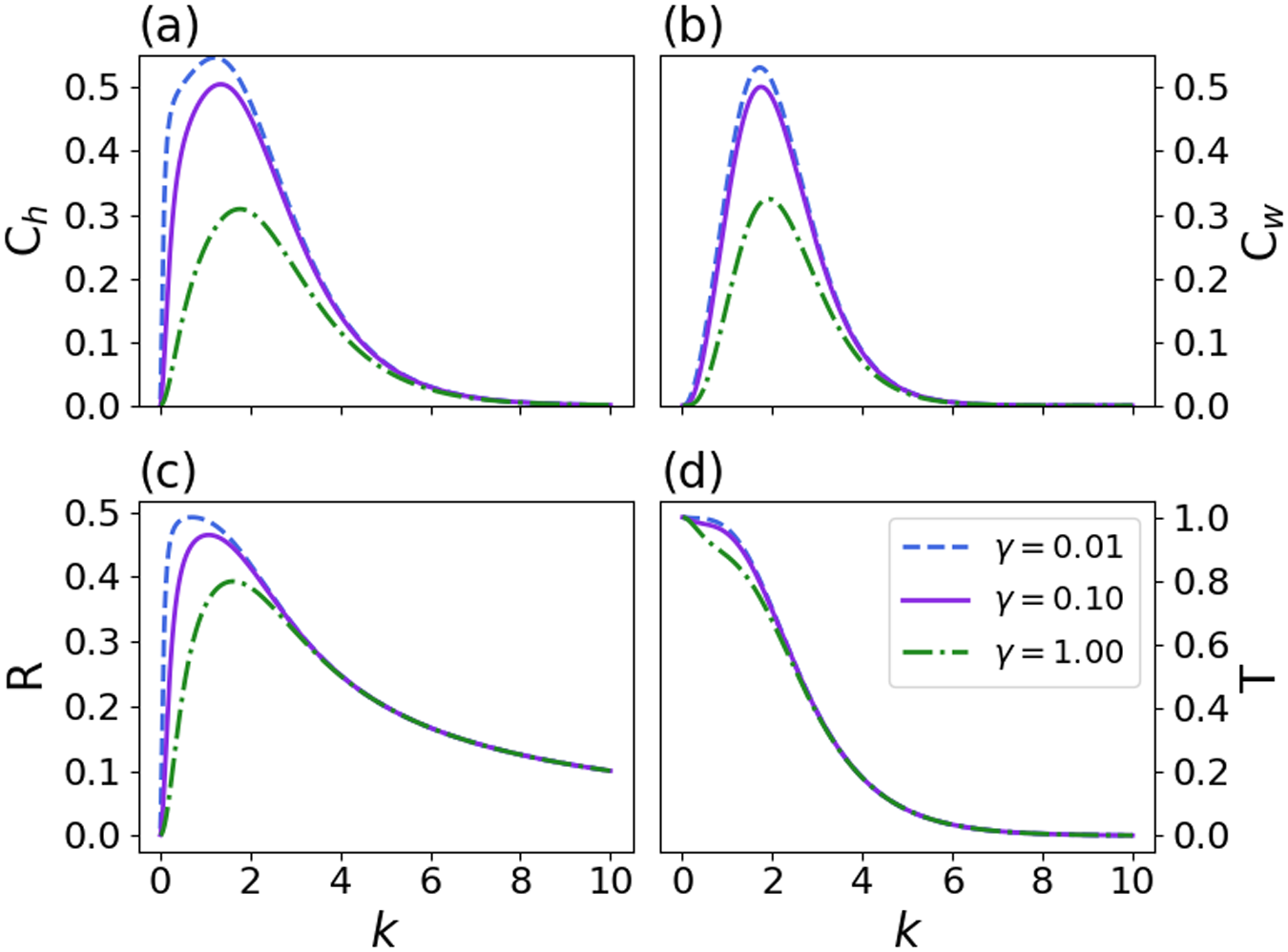

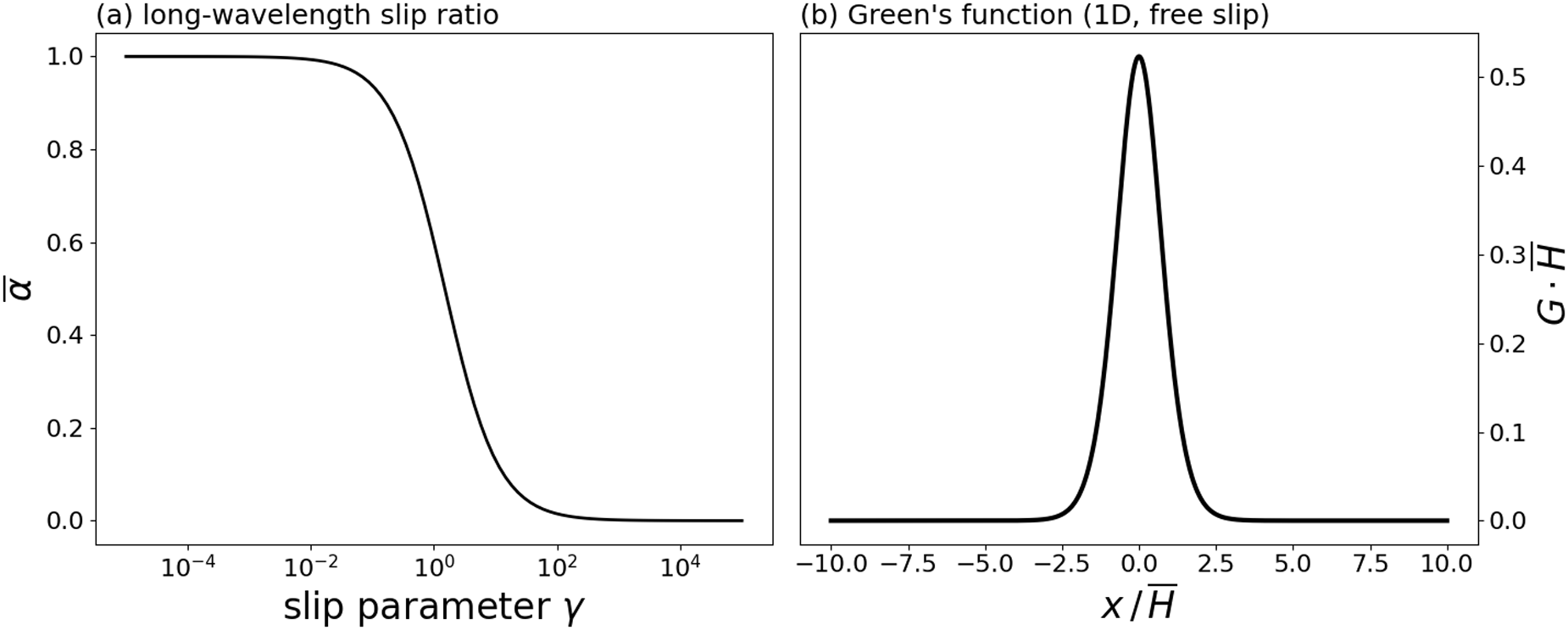

$\mathsf{C}_w$ decay at larger values of the sliding parameter ![]() $\gamma$, which leads to diminished viscous stresses at the base (Fig. 3a,b).

$\gamma$, which leads to diminished viscous stresses at the base (Fig. 3a,b).

Figure 3. (a,b) Functions ![]() $\mathsf{C}_h$ and

$\mathsf{C}_h$ and ![]() $\mathsf{C}_w$ (Eqns. 15-16) that determine the Fourier-transformed effective pressure

$\mathsf{C}_w$ (Eqns. 15-16) that determine the Fourier-transformed effective pressure ![]() $\widehat{N}$ (Eqn. 18) as functions of the scaled wavevector magnitude

$\widehat{N}$ (Eqn. 18) as functions of the scaled wavevector magnitude ![]() $k$ for different values of the nondimensional parameter

$k$ for different values of the nondimensional parameter ![]() $\gamma = {{\beta}H}/({2\eta})$. (c,d) Functions

$\gamma = {{\beta}H}/({2\eta})$. (c,d) Functions ![]() $\mathsf{R}$ and

$\mathsf{R}$ and ![]() $\mathsf{T}$ (Eqns. 23-24) that determine the Fourier-transformed elevation-change anomaly

$\mathsf{T}$ (Eqns. 23-24) that determine the Fourier-transformed elevation-change anomaly ![]() $\widehat{\Delta h}$ (Eqn. 22) for different values of

$\widehat{\Delta h}$ (Eqn. 22) for different values of ![]() $\gamma$. All functions are nondimensional.

$\gamma$. All functions are nondimensional.

We combine Eqns. (13) and (14) to obtain a formula for the Fourier-transformed effective pressure,

\begin{equation}

\widehat{N} = \tfrac{2\eta}{\bar{H}}\mathsf{C}_w \widehat{w_\mathrm{b}} - {\rho_\mathrm{i}g}\mathsf{C}_h \widehat{\Delta h}

+ g\Delta\rho\,\left(\widehat{s}- {\bar{s}}\widehat{\chi}\right),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\widehat{N} = \tfrac{2\eta}{\bar{H}}\mathsf{C}_w \widehat{w_\mathrm{b}} - {\rho_\mathrm{i}g}\mathsf{C}_h \widehat{\Delta h}

+ g\Delta\rho\,\left(\widehat{s}- {\bar{s}}\widehat{\chi}\right),

\end{equation} where we have assumed that the basal surface perturbation vanishes outside the lake boundary (![]() $s=s\chi$). The potential correlation between the effective pressure and the basal vertical velocity in (18) is analogous to the bending of an elastic beam (Evatt and Fowler, Reference Evatt and Fowler2007). In particular, upward motion (

$s=s\chi$). The potential correlation between the effective pressure and the basal vertical velocity in (18) is analogous to the bending of an elastic beam (Evatt and Fowler, Reference Evatt and Fowler2007). In particular, upward motion (![]() $w_\mathrm{b} \gt 0$) can result in compression (

$w_\mathrm{b} \gt 0$) can result in compression (![]() $N \gt 0$) at the base and downward motion can result in tension, although the precise level of correlation depends on the magnitude of the viscous term relative to the elevation-dependent terms. In Appendix C, we show that the opposite behaviour arises where the basal vertical velocity is proportional to the negative effective pressure in the limit of steady creep, which is consistent with commonly used creep closure laws for subglacial channels and other drainage elements (Nye, Reference Nye1976; Hewitt, Reference Hewitt2011). A simple, alternative interpretation relates the effective pressure to dynamic thickness changes, which are calculated implicitly with this method (Appendix B).

$N \gt 0$) at the base and downward motion can result in tension, although the precise level of correlation depends on the magnitude of the viscous term relative to the elevation-dependent terms. In Appendix C, we show that the opposite behaviour arises where the basal vertical velocity is proportional to the negative effective pressure in the limit of steady creep, which is consistent with commonly used creep closure laws for subglacial channels and other drainage elements (Nye, Reference Nye1976; Hewitt, Reference Hewitt2011). A simple, alternative interpretation relates the effective pressure to dynamic thickness changes, which are calculated implicitly with this method (Appendix B).

Following previous work, we obtain the basal vertical velocity ![]() $w_\mathrm{b}$ from elevation-change data

$w_\mathrm{b}$ from elevation-change data ![]() $\Delta h$ with an inverse method that follows the linearised approach taken herein (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). The ice-base elevation

$\Delta h$ with an inverse method that follows the linearised approach taken herein (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). The ice-base elevation ![]() $s$ is determined up to an initial condition

$s$ is determined up to an initial condition ![]() $s_0$ by

$s_0$ by

\begin{equation}

s = s_0 + \int_0^t {w}_\mathrm{b} \;\mathrm{d}t',

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

s = s_0 + \int_0^t {w}_\mathrm{b} \;\mathrm{d}t',

\end{equation} where we have neglected a small advective component from the background flow under the assumption that the ice–water interface motion is caused by the basal vertical velocity from water-volume changes (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). We can calculate the effective pressure from Eqn. (18) after specifying the initial conditions and auxiliary parameters (![]() $H$,

$H$, ![]() $\eta$,

$\eta$, ![]() $\beta$,

$\beta$, ![]() $\bar{\pmb{u}}$) that the inverse method requires, where

$\bar{\pmb{u}}$) that the inverse method requires, where ![]() $\bar{\pmb{u}}$ is the mean ice surface velocity in the base state (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). We provide a simplified analysis of Eqn. (18) in the following section for illustration, while a complete description of the inverse method is provided by Stubblefield and others (Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a).

$\bar{\pmb{u}}$ is the mean ice surface velocity in the base state (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). We provide a simplified analysis of Eqn. (18) in the following section for illustration, while a complete description of the inverse method is provided by Stubblefield and others (Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a).

3. Analysis

Before applying the estimation method to Antarctic subglacial lakes (Fig. 2), we first analyse the effective pressure ![]() $N$ (Eqn. 18) in relation to the basal vertical velocity

$N$ (Eqn. 18) in relation to the basal vertical velocity ![]() $w_\mathrm{b}$. We then explore a synthetic example that falls within the parameter regime of the Antarctic subglacial lakes.

$w_\mathrm{b}$. We then explore a synthetic example that falls within the parameter regime of the Antarctic subglacial lakes.

3.1. Scaling

First, we scale Eqn. (18) to facilitate the analysis below. For simplicity, we refrain from renaming the nondimensional variables. We let ![]() $[h]$ be the elevation anomaly scale (1 m) and

$[h]$ be the elevation anomaly scale (1 m) and ![]() $[t]$ be the observational time scale (1 yr). We scale the map-plane coordinates

$[t]$ be the observational time scale (1 yr). We scale the map-plane coordinates ![]() $(x,y)$ by

$(x,y)$ by ![]() $H$, the effective pressure by

$H$, the effective pressure by ![]() $[N] = \rho_\mathrm{i}g [h]$, and the vertical velocity by

$[N] = \rho_\mathrm{i}g [h]$, and the vertical velocity by ![]() $[w_\mathrm{b}] = [h] [t]^{-1}$. With this scaling, Eqn. (18) becomes

$[w_\mathrm{b}] = [h] [t]^{-1}$. With this scaling, Eqn. (18) becomes

\begin{equation}

\widehat{N} = \frac{1}{\lambda}\mathsf{C}_w \widehat{w_\mathrm{b}} - \mathsf{C}_h \widehat{\Delta h}

+ \delta\left(\widehat{s} - \bar{s}\widehat{\chi}\right),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\widehat{N} = \frac{1}{\lambda}\mathsf{C}_w \widehat{w_\mathrm{b}} - \mathsf{C}_h \widehat{\Delta h}

+ \delta\left(\widehat{s} - \bar{s}\widehat{\chi}\right),

\end{equation} where we have defined the flotation factor ![]() $\delta = \rho_\mathrm{w}/\rho_\mathrm{i}-1$. The parameter

$\delta = \rho_\mathrm{w}/\rho_\mathrm{i}-1$. The parameter ![]() $\lambda$ is defined by the ratio

$\lambda$ is defined by the ratio

\begin{equation}

\lambda = \frac{[t]}{t_\mathrm{relax}},\qquad t_\mathrm{relax} = \frac{2\eta}{\rho_\mathrm{i}g \bar{H}},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\lambda = \frac{[t]}{t_\mathrm{relax}},\qquad t_\mathrm{relax} = \frac{2\eta}{\rho_\mathrm{i}g \bar{H}},

\end{equation} where ![]() $t_\mathrm{relax}$ is the timescale for viscous relaxation (decay) of topography (Turcotte and Schubert, Reference Turcotte and Schubert2014; Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Creyts, Kingslake, Siegfried and Spiegelman2021a; Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). The scaling in Eqn. (20) shows that the precise definition of the lake boundary is of lesser importance in determining the effective pressure since it only manifests in the smaller, hydrostatic term that is multiplied by the flotation factor. However, careful consideration of the lake boundary is important for determining where the underlying approximations are valid. Additionally, any suspended sediment in the water column could potentially increase the fluid density, making the hydrostatic term more important.

$t_\mathrm{relax}$ is the timescale for viscous relaxation (decay) of topography (Turcotte and Schubert, Reference Turcotte and Schubert2014; Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Creyts, Kingslake, Siegfried and Spiegelman2021a; Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). The scaling in Eqn. (20) shows that the precise definition of the lake boundary is of lesser importance in determining the effective pressure since it only manifests in the smaller, hydrostatic term that is multiplied by the flotation factor. However, careful consideration of the lake boundary is important for determining where the underlying approximations are valid. Additionally, any suspended sediment in the water column could potentially increase the fluid density, making the hydrostatic term more important.

3.2. Closure relations

Next, we examine relations between the effective pressure and basal vertical velocity, which are related in subglacial hydrology models through creep closure laws (e.g.,

Nye, Reference Nye1976; Evatt, Reference Evatt2015; Meyer and others, Reference Meyer, Fernandes, Creyts and Rice2016). We outline how our formulation reduces to a similar form as the previously derived closure laws under certain simplifying assumptions in Appendix C. For simplicity, we assume here that there is no ice advection in the background state (![]() $\bar{\pmb{u}}=0$) and no initial surface perturbations (

$\bar{\pmb{u}}=0$) and no initial surface perturbations (![]() $\Delta h = s = 0$ at

$\Delta h = s = 0$ at ![]() $t=0$). The general case has been previously covered (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). Under these assumptions, the elevation change is related to the basal vertical velocity by

$t=0$). The general case has been previously covered (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). Under these assumptions, the elevation change is related to the basal vertical velocity by

\begin{equation}

\widehat{\Delta h} = \mathsf{T} \widehat{w_{\mathrm{b}}} * \exp\left(-\lambda\mathsf{R} \, t\right),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\widehat{\Delta h} = \mathsf{T} \widehat{w_{\mathrm{b}}} * \exp\left(-\lambda\mathsf{R} \, t\right),

\end{equation} where ![]() $*$ denotes convolution over time (Appendix A).

$*$ denotes convolution over time (Appendix A).

In Eqn. (22), ![]() $\mathsf{R}$ describes viscous decay of surface topography (Fig. 3c) while

$\mathsf{R}$ describes viscous decay of surface topography (Fig. 3c) while ![]() $\mathsf{T}$ is a base-to-surface transfer function (Fig. 3d). These functions depend on the wavenumber

$\mathsf{T}$ is a base-to-surface transfer function (Fig. 3d). These functions depend on the wavenumber ![]() $k$ and nondimensional sliding parameter

$k$ and nondimensional sliding parameter ![]() $\gamma$ via

$\gamma$ via

\begin{equation}

\mathsf{R} = \frac{1}{k}\frac{(k+\gamma)e^{4{k}} -(2+4\gamma ){k}e^{2{k}} +k-\gamma }{\left(k+{\gamma}\right) e^{4

k} + 2\left({\gamma} + 2 ({1+\gamma}) k^{2} \right) e^{2 k} - \left(k-{\gamma}\right)},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mathsf{R} = \frac{1}{k}\frac{(k+\gamma)e^{4{k}} -(2+4\gamma ){k}e^{2{k}} +k-\gamma }{\left(k+{\gamma}\right) e^{4

k} + 2\left({\gamma} + 2 ({1+\gamma}) k^{2} \right) e^{2 k} - \left(k-{\gamma}\right)},

\end{equation} \begin{equation}

\mathsf{T} = \frac{2(k+\gamma)({k}+1)e^{3{k}}+2(k-\gamma)({k}-1)e^{{k}} }{\left(k+{\gamma}\right) e^{4

k} + 2\left({\gamma} + 2 ({1+\gamma}) k^{2} \right) e^{2 k} - \left(k-{\gamma}\right)}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mathsf{T} = \frac{2(k+\gamma)({k}+1)e^{3{k}}+2(k-\gamma)({k}-1)e^{{k}} }{\left(k+{\gamma}\right) e^{4

k} + 2\left({\gamma} + 2 ({1+\gamma}) k^{2} \right) e^{2 k} - \left(k-{\gamma}\right)}.

\end{equation}The functions (23)-(24) are rewritten slightly from previous work due to the scaling adopted herein (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). The elevation-change formula (22) provides the basis for the least-squares inverse method for obtaining the basal vertical velocity (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). Substituting the relations (19) and (22) into Eqn. (20), we obtain

\begin{align}

\widehat{N} &= \tfrac{1}{\lambda}\mathsf{C}_w \widehat{w_\mathrm{b}} - \mathsf{C}_h \left[ \mathsf{T} \widehat{w_\mathrm{b}} * \exp\left(-\lambda\mathsf{R} \, t\right) \right] \nonumber\\

&\quad + \delta \left(\int\limits_0^t \widehat{w_\mathrm{b}}

-\tfrac{1}{|L|} \widehat{w_\mathrm{b}}\big|_{k=0}\, \widehat{\chi} \;\mathrm{d}t' \, \right),

\end{align}

\begin{align}

\widehat{N} &= \tfrac{1}{\lambda}\mathsf{C}_w \widehat{w_\mathrm{b}} - \mathsf{C}_h \left[ \mathsf{T} \widehat{w_\mathrm{b}} * \exp\left(-\lambda\mathsf{R} \, t\right) \right] \nonumber\\

&\quad + \delta \left(\int\limits_0^t \widehat{w_\mathrm{b}}

-\tfrac{1}{|L|} \widehat{w_\mathrm{b}}\big|_{k=0}\, \widehat{\chi} \;\mathrm{d}t' \, \right),

\end{align}which provides a direct relation between the effective pressure and basal vertical velocity. In the limit of steady creep, Eqn. (25) reduces to a similar form relative to previous closure laws, where the closure rate is proportional to the negative effective pressure (Appendix C).

3.3. Sinusoidal oscillations

As a semi-analytical example, we assume that the basal vertical velocity oscillates in time according to

where ![]() $W$ denotes the spatial pattern of the basal vertical velocity anomaly. We assume that the lake is radially symmetric with radius

$W$ denotes the spatial pattern of the basal vertical velocity anomaly. We assume that the lake is radially symmetric with radius ![]() ${r}$ and surface area

${r}$ and surface area ![]() $|L| = \pi {r}^2$, which implies that the indicator function

$|L| = \pi {r}^2$, which implies that the indicator function ![]() $\chi$ transforms to

$\chi$ transforms to

\begin{equation}

\widehat{\chi} = 2\pi {r}^2 \frac{J_1(k{r})}{k{r}},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\widehat{\chi} = 2\pi {r}^2 \frac{J_1(k{r})}{k{r}},

\end{equation} where ![]() $J_1$ is the order-one Bessel function of the first kind.

$J_1$ is the order-one Bessel function of the first kind.

We insert (26)-(27) into Eqn. (25), calculate the integrals and neglect an exponential decay term (proportional to ![]() $\mathsf{C}_h$) to obtain the long-time behaviour (

$\mathsf{C}_h$) to obtain the long-time behaviour (![]() $\lambda \mathsf{R} t\gg 1$)

$\lambda \mathsf{R} t\gg 1$)

\begin{align}

{\widehat{N}}(k,t) &= \left[\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{in} \cos(\omega t) - \mathsf{E}_\mathrm{out} \sin(\omega t)\right]\widehat{W}(k) \nonumber\\

&\quad + \frac{\delta}{\omega}\left[\widehat{W}(k) - \frac{2 J_1(k{r})}{k{r}} \widehat{W}(0)\right] \sin(\omega t),

\end{align}

\begin{align}

{\widehat{N}}(k,t) &= \left[\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{in} \cos(\omega t) - \mathsf{E}_\mathrm{out} \sin(\omega t)\right]\widehat{W}(k) \nonumber\\

&\quad + \frac{\delta}{\omega}\left[\widehat{W}(k) - \frac{2 J_1(k{r})}{k{r}} \widehat{W}(0)\right] \sin(\omega t),

\end{align} \begin{equation}

\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{in} = \frac{1}{\lambda}\mathsf{C}_w - \frac{\mathsf{C}_h\mathsf{T}\,\lambda\mathsf{R}}{\omega^2 + \lambda^2\mathsf{R}^2}, \qquad

\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{out} = \frac{\mathsf{C}_h\mathsf{T}\,\omega}{\omega^2 + \lambda^2\mathsf{R}^2}.

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{in} = \frac{1}{\lambda}\mathsf{C}_w - \frac{\mathsf{C}_h\mathsf{T}\,\lambda\mathsf{R}}{\omega^2 + \lambda^2\mathsf{R}^2}, \qquad

\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{out} = \frac{\mathsf{C}_h\mathsf{T}\,\omega}{\omega^2 + \lambda^2\mathsf{R}^2}.

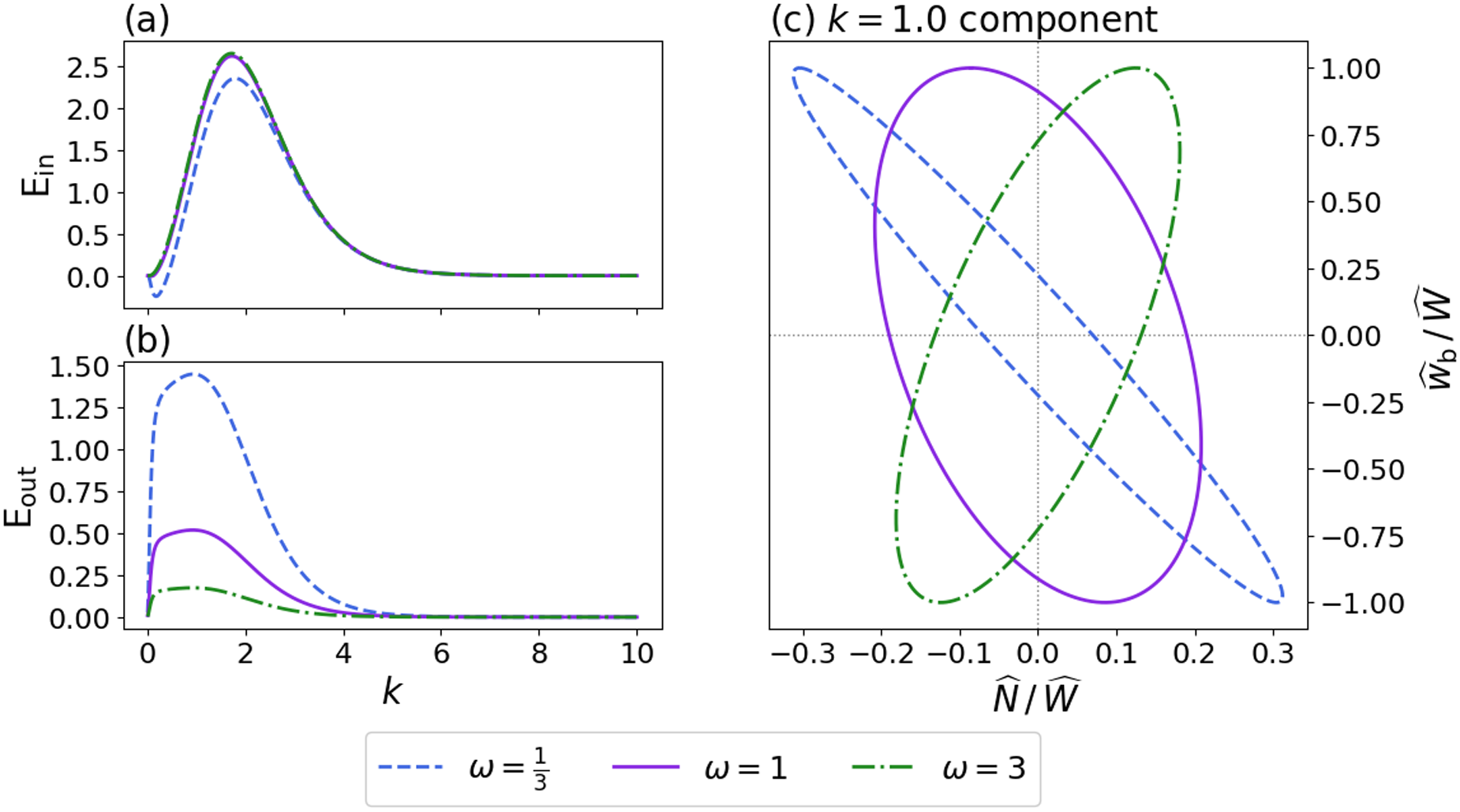

\end{equation} We plot the in-phase component ![]() $\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{in}$ and out-of-phase component

$\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{in}$ and out-of-phase component ![]() $\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{out}$ for various oscillation frequencies

$\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{out}$ for various oscillation frequencies ![]() $\omega$ in Figure 4. The in-phase component

$\omega$ in Figure 4. The in-phase component ![]() $\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{in}$ decreases as the oscillation frequency

$\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{in}$ decreases as the oscillation frequency ![]() $\omega$ decreases. For all oscillation frequencies, the in-phase component decays to zero at short wavelengths and in the long-wavelength limit (Fig. 4a). The out-of-phase component

$\omega$ decreases. For all oscillation frequencies, the in-phase component decays to zero at short wavelengths and in the long-wavelength limit (Fig. 4a). The out-of-phase component ![]() $\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{out}$ increases at slower oscillation frequencies (Fig. 4b). The spectra of the effective pressure and basal vertical velocity can be positively correlated, negatively correlated or uncorrelated, depending on the oscillation frequency and spatial wavenumber (Fig. 4c).

$\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{out}$ increases at slower oscillation frequencies (Fig. 4b). The spectra of the effective pressure and basal vertical velocity can be positively correlated, negatively correlated or uncorrelated, depending on the oscillation frequency and spatial wavenumber (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4. (a) In phase component ![]() $\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{in}$ and (b) out-of-phase component

$\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{in}$ and (b) out-of-phase component ![]() $\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{out}$ of the effective pressure spectrum (28) for different oscillation frequencies

$\mathsf{E}_\mathrm{out}$ of the effective pressure spectrum (28) for different oscillation frequencies ![]() $\omega$. The nondimensional parameters are set to

$\omega$. The nondimensional parameters are set to ![]() $\gamma=0.01$ and

$\gamma=0.01$ and ![]() $\lambda = 0.2$. (c) Effective pressure spectrum versus vertical velocity spectrum (

$\lambda = 0.2$. (c) Effective pressure spectrum versus vertical velocity spectrum (![]() $k=1$ component), normalised by the spectral amplitude of the vertical velocity

$k=1$ component), normalised by the spectral amplitude of the vertical velocity ![]() $\widehat{W}$. For this value of

$\widehat{W}$. For this value of ![]() $k=1$, we set the long-wavelength term to

$k=1$, we set the long-wavelength term to ![]() $\widehat{W}(0)=16\times\widehat{W}(k)$ in Eqn. (28), which corresponds to the Gaussian-shaped anomaly in Figure 5.

$\widehat{W}(0)=16\times\widehat{W}(k)$ in Eqn. (28), which corresponds to the Gaussian-shaped anomaly in Figure 5.

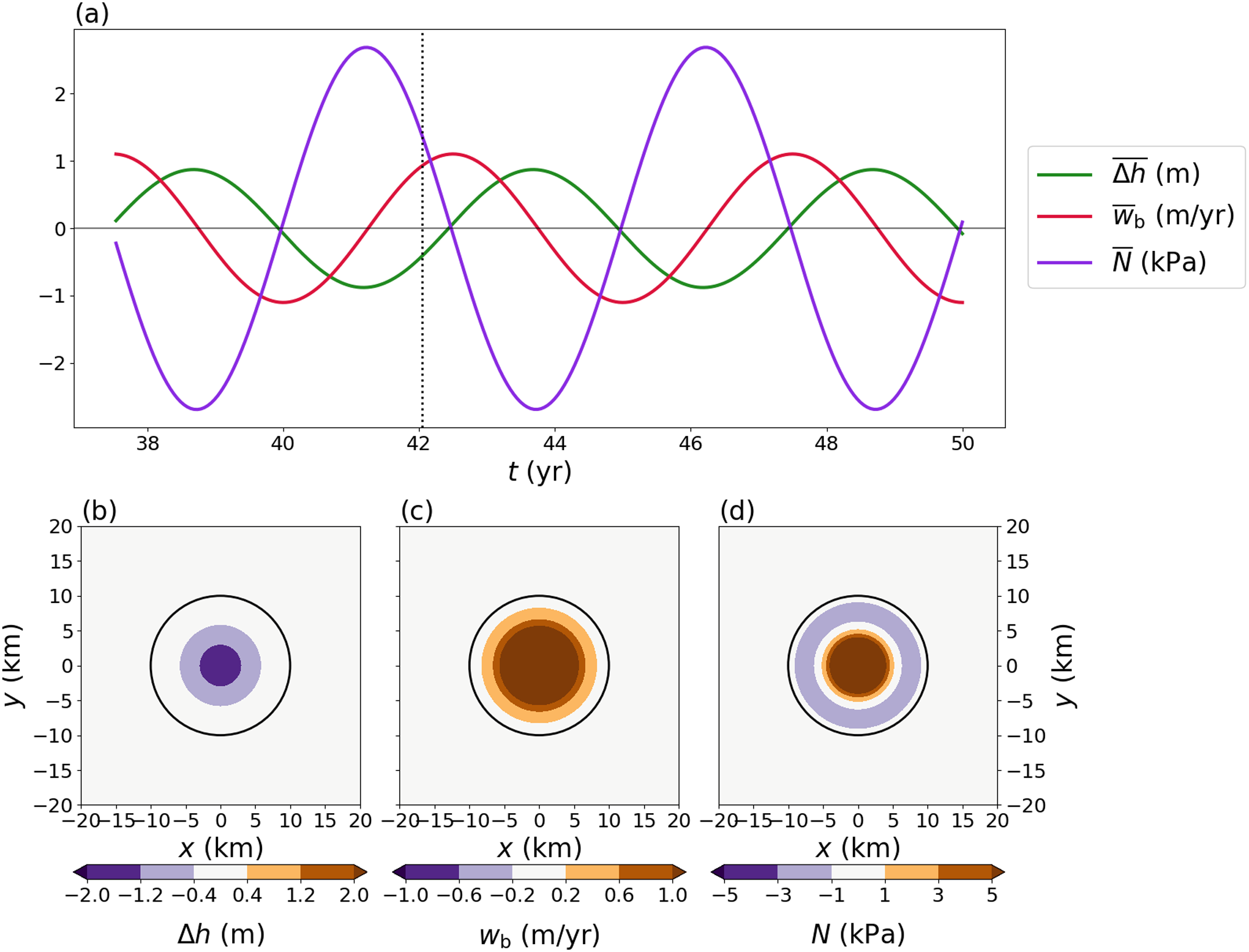

3.4. Synthetic example

To translate the preceding analysis to physical space, we consider a synthetic example with a Gaussian-shaped basal vertical velocity that exhibits sinusoidal oscillations in time (Fig. 5). In dimensional terms, the basal vertical velocity ![]() $w_\mathrm{b}$ has a width of

$w_\mathrm{b}$ has a width of ![]() $\sim$20 km, amplitude of

$\sim$20 km, amplitude of ![]() $5$ m yr

$5$ m yr![]() $^{-1}$ and oscillation period of 5 yr. While the relation between the effective pressure

$^{-1}$ and oscillation period of 5 yr. While the relation between the effective pressure ![]() $N$ and basal vertical velocity

$N$ and basal vertical velocity ![]() $w_\mathrm{b}$ depends on the nondimensional parameters, we consider the values

$w_\mathrm{b}$ depends on the nondimensional parameters, we consider the values ![]() $\lambda=0.2$ and

$\lambda=0.2$ and ![]() $\gamma=0.01$, which fall within the range of values for the Antarctic subglacial lakes discussed below (Table 1). The effective pressure is influenced by both the elevation-change anomaly (Fig. 5b) and the basal vertical velocity (Fig. 5c), but can be more strongly correlated with one over the other, depending on the parameter values. For these parameters, the mean effective pressure is negatively correlated with the elevation-change anomaly over time (Fig. 5a). Due to the combined influence of the basal velocity and elevation change, positive and negative values of the effective pressure can exist within the lake boundary simultaneously. For example, a ring-shaped region of negative effective pressure forms near the boundary of the lake at the start of the filling stages (Fig. 5d). Similar behaviour with the opposite sign can occur during the draining stages.

$\gamma=0.01$, which fall within the range of values for the Antarctic subglacial lakes discussed below (Table 1). The effective pressure is influenced by both the elevation-change anomaly (Fig. 5b) and the basal vertical velocity (Fig. 5c), but can be more strongly correlated with one over the other, depending on the parameter values. For these parameters, the mean effective pressure is negatively correlated with the elevation-change anomaly over time (Fig. 5a). Due to the combined influence of the basal velocity and elevation change, positive and negative values of the effective pressure can exist within the lake boundary simultaneously. For example, a ring-shaped region of negative effective pressure forms near the boundary of the lake at the start of the filling stages (Fig. 5d). Similar behaviour with the opposite sign can occur during the draining stages.

Figure 5. Synthetic example with nondimensional parameters ![]() $\gamma=0.01$ and

$\gamma=0.01$ and ![]() $\lambda=0.2$. (a) Time series of the mean elevation change, basal vertical velocity and effective pressure over the lake. (b)–(d) Map-plane plots of elevation change, basal vertical velocity and effective pressure at the time noted by the dashed vertical line in (a). The lake boundary is shown by the black circle.

$\lambda=0.2$. (a) Time series of the mean elevation change, basal vertical velocity and effective pressure over the lake. (b)–(d) Map-plane plots of elevation change, basal vertical velocity and effective pressure at the time noted by the dashed vertical line in (a). The lake boundary is shown by the black circle.

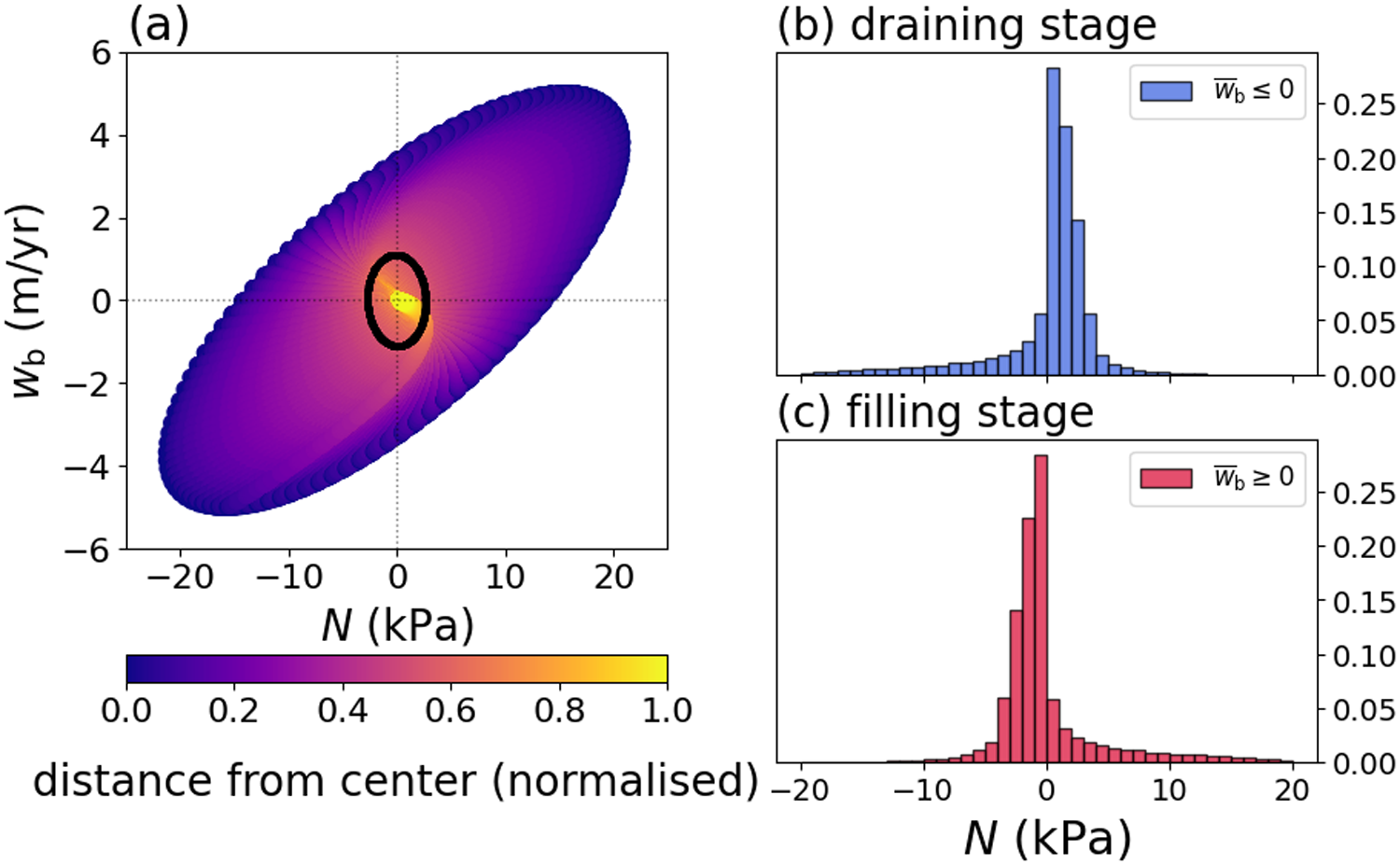

Table 1. Main parameters used in calculating the effective pressures of the Antarctic subglacial lakes (Figure 2). Data sources are provided in the ‘Data availability’ statement. The ‘Data’ section in the main text describes pre-processing of the elevation-change data and estimation of the ice-flow parameters (viscosity and basal drag). The off-lake pressure estimates ![]() ${\bar{N}_\mathrm{off}}$ are defined in Eqn. (30). The nondimensional parameters are defined by

${\bar{N}_\mathrm{off}}$ are defined in Eqn. (30). The nondimensional parameters are defined by ![]() $\gamma = {{\beta}{\bar{H}}}/({2{\eta}})$ (Eqn. 17) and

$\gamma = {{\beta}{\bar{H}}}/({2{\eta}})$ (Eqn. 17) and ![]() $\lambda = {\rho_\mathrm{i}gH [t]}/({2\eta})$ (Eqn. 21) where the observational timescale is

$\lambda = {\rho_\mathrm{i}gH [t]}/({2\eta})$ (Eqn. 21) where the observational timescale is ![]() $[t]=1$ yr. Parameter values are multiplied by the amount specified in the ‘units’ column.

$[t]=1$ yr. Parameter values are multiplied by the amount specified in the ‘units’ column.

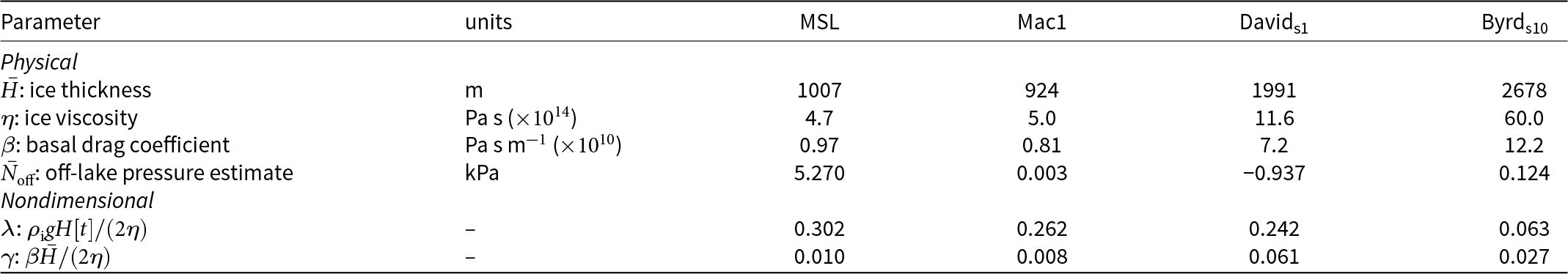

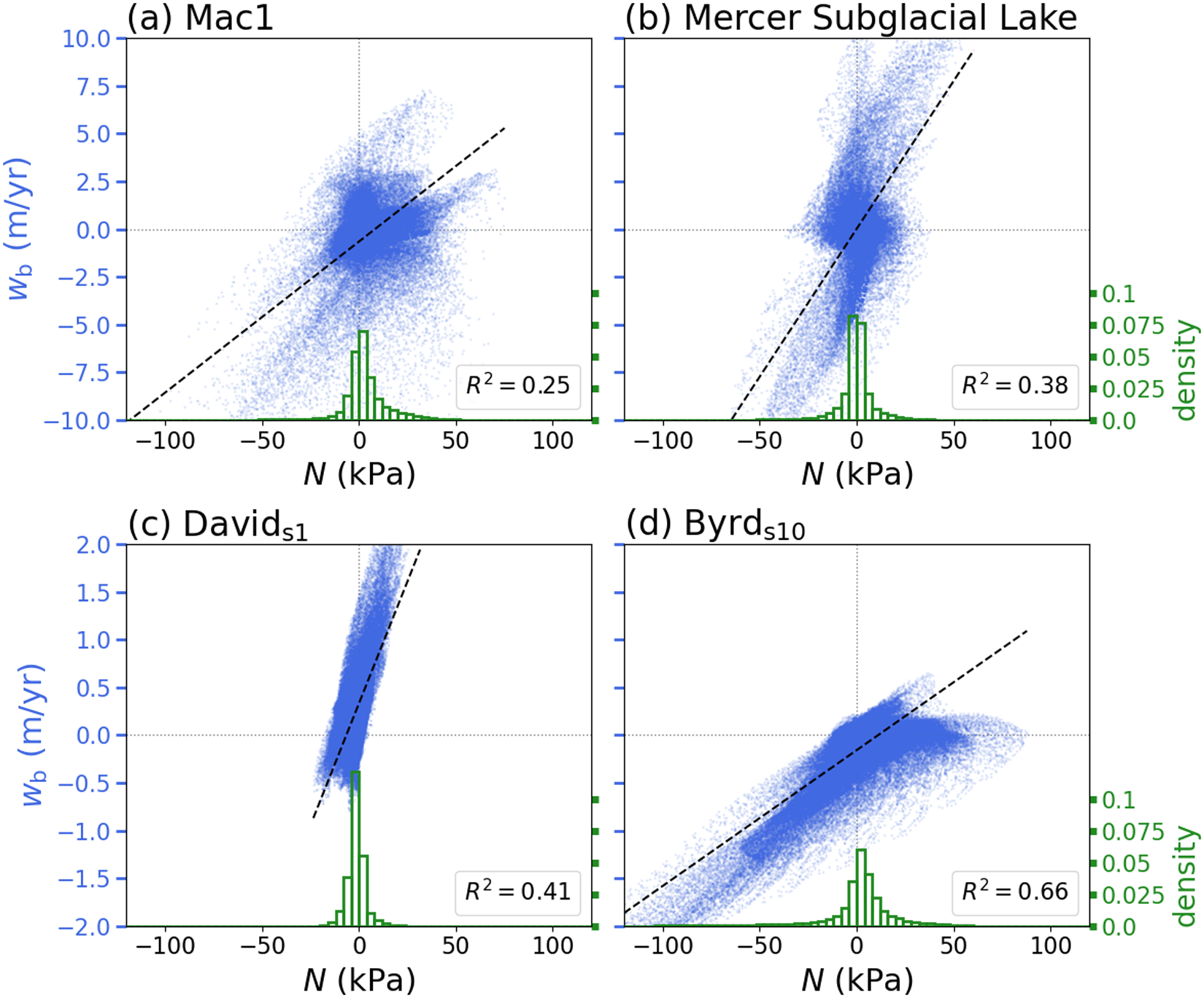

The largest magnitudes of ![]() $N$ and

$N$ and ![]() $w_\mathrm{b}$ occur near the centre of the lake where the deformation is largest, while the mean behaviour over the lake has a smaller magnitude that more closely corresponds to the behaviour near the lake boundary (Figs. 5 and 6a). In particular, the mean values of

$w_\mathrm{b}$ occur near the centre of the lake where the deformation is largest, while the mean behaviour over the lake has a smaller magnitude that more closely corresponds to the behaviour near the lake boundary (Figs. 5 and 6a). In particular, the mean values of ![]() $w_\mathrm{b}$ and

$w_\mathrm{b}$ and ![]() $N$ over the lake show a weaker correlation than the pointwise behaviour near the centre of the lake (Fig. 6a).

$N$ over the lake show a weaker correlation than the pointwise behaviour near the centre of the lake (Fig. 6a).

We compare histograms of the effective pressure for all spatiotemporal points during the draining stage (![]() $\bar{w}_\mathrm{b}\leq 0$) and the filling stage (

$\bar{w}_\mathrm{b}\leq 0$) and the filling stage (![]() $\bar{w}_\mathrm{b}\geq 0$) to highlight the bulk behaviour of the system (Fig. 6b-c). The effective pressure distribution has a peak around

$\bar{w}_\mathrm{b}\geq 0$) to highlight the bulk behaviour of the system (Fig. 6b-c). The effective pressure distribution has a peak around ![]() $1$ kPa during draining stages (

$1$ kPa during draining stages (![]() $\bar{w}_\mathrm{b}\leq 0$), accompanied by a long tail of negative values (Fig. 6b). During filling stages (

$\bar{w}_\mathrm{b}\leq 0$), accompanied by a long tail of negative values (Fig. 6b). During filling stages (![]() $\bar{w}_\mathrm{b}\geq 0$), the effective pressure distribution has a peak around

$\bar{w}_\mathrm{b}\geq 0$), the effective pressure distribution has a peak around ![]() $-1$ kPa that is accompanied by a long tail of positive values (Fig. 6c). For these parameters (

$-1$ kPa that is accompanied by a long tail of positive values (Fig. 6c). For these parameters (![]() $\lambda=0.2$ and

$\lambda=0.2$ and ![]() $\gamma=0.01$), the effective pressure falls within

$\gamma=0.01$), the effective pressure falls within ![]() $\pm 20$ kPa, which is a relatively small deviation from flotation (

$\pm 20$ kPa, which is a relatively small deviation from flotation (![]() $N=0$).

$N=0$).

Figure 6. (a) Basal vertical velocity ![]() $w_\mathrm{b}$ versus the effective pressure

$w_\mathrm{b}$ versus the effective pressure ![]() $N$ in the synthetic example (Figure 5) for different values of

$N$ in the synthetic example (Figure 5) for different values of ![]() $\lambda$. The nondimensional parameters are set to

$\lambda$. The nondimensional parameters are set to ![]() $\gamma=0.01$ and

$\gamma=0.01$ and ![]() $\lambda=0.2$. The colours of the points show the distance from the centre of the lake normalised by the distance to the boundary. The black ellipse corresponds to the spatial mean over the lake at each point in time. (b) Histogram of the effective pressure during the draining stages (

$\lambda=0.2$. The colours of the points show the distance from the centre of the lake normalised by the distance to the boundary. The black ellipse corresponds to the spatial mean over the lake at each point in time. (b) Histogram of the effective pressure during the draining stages (![]() $\overline{w}_\mathrm{b}\leq 0$) normalised by the total number of spatiotemporal points. (c) Histogram of the effective pressure during the filling stages (

$\overline{w}_\mathrm{b}\leq 0$) normalised by the total number of spatiotemporal points. (c) Histogram of the effective pressure during the filling stages (![]() $\overline{w}_\mathrm{b}\geq 0$) normalised by the total number of spatiotemporal points.

$\overline{w}_\mathrm{b}\geq 0$) normalised by the total number of spatiotemporal points.

4. Antarctic examples

4.1. Data

We use Eqn. (18) to calculate the effective pressure ![]() $N$ from the elevation-change anomalies

$N$ from the elevation-change anomalies ![]() $\Delta h$ and the basal vertical velocity inversions

$\Delta h$ and the basal vertical velocity inversions ![]() $w_\mathrm{b}$ over several Antarctic subglacial lakes (Fig. 2). The preprocessing of the elevation-change data and the inversion for the basal vertical velocity are described in detail by Stubblefield and others (Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). We use the ICESat-2 ATL15 L3B Gridded Antarctic and Arctic Land Ice Height Change (Version 4) data product (Smith and others, Reference Smith, Jelley, Dickinson, Sutterley, Neumann and Harbeck2024) to obtain elevation-change anomalies over the lakes by removing any regional thinning or thickening trend (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). We linearly interpolate the ATL15 data onto the fine spatiotemporal grid of the inverse method, which could produce errors in the pressure estimates if lake activity occurs more rapidly than the temporal resolution of ICESat-2 (91-day repeat cycle).

$w_\mathrm{b}$ over several Antarctic subglacial lakes (Fig. 2). The preprocessing of the elevation-change data and the inversion for the basal vertical velocity are described in detail by Stubblefield and others (Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). We use the ICESat-2 ATL15 L3B Gridded Antarctic and Arctic Land Ice Height Change (Version 4) data product (Smith and others, Reference Smith, Jelley, Dickinson, Sutterley, Neumann and Harbeck2024) to obtain elevation-change anomalies over the lakes by removing any regional thinning or thickening trend (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). We linearly interpolate the ATL15 data onto the fine spatiotemporal grid of the inverse method, which could produce errors in the pressure estimates if lake activity occurs more rapidly than the temporal resolution of ICESat-2 (91-day repeat cycle).

Removing any regional thickness-change trend is necessary for the inverse method and coincides with the assumption of flotation (![]() $N=0$) in the base state. To provide an independent point of comparison for the results, we use the approximation (B.1) that relates effective pressure to dynamic thickness changes (Appendix B) to estimate an ambient effective pressure via

$N=0$) in the base state. To provide an independent point of comparison for the results, we use the approximation (B.1) that relates effective pressure to dynamic thickness changes (Appendix B) to estimate an ambient effective pressure via

\begin{equation}

\bar{N}_\mathrm{off} = \frac{2\eta}{\bar{H}}\frac{\Delta H_\mathrm{off} }{\Delta t},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\bar{N}_\mathrm{off} = \frac{2\eta}{\bar{H}}\frac{\Delta H_\mathrm{off} }{\Delta t},

\end{equation} where ![]() $\Delta H_\mathrm{off}$ is the off-lake thickness change over the duration

$\Delta H_\mathrm{off}$ is the off-lake thickness change over the duration ![]() $\Delta t$ (5 years). We compute the off-lake thickness change by taking the spatial average of the ATL15 elevation-change product over all points that are at a distance greater than 80% from the centroid of the lake to the boundary of the computational domain (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Creyts, Kingslake, Siegfried and Spiegelman2021a). In the estimate (30), we have assumed a slip ratio of one and that all thickness changes arise from ice dynamics rather than snow accumulation (see Appendix B); removing any contributions from snow accumulation or assuming a smaller slip ratio would decrease the magnitude of the off-lake pressure estimates. We find that these estimates are at most only a few kilopascals in magnitude (Table 1), which is consistent with our results and underlying assumptions.

$\Delta t$ (5 years). We compute the off-lake thickness change by taking the spatial average of the ATL15 elevation-change product over all points that are at a distance greater than 80% from the centroid of the lake to the boundary of the computational domain (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Creyts, Kingslake, Siegfried and Spiegelman2021a). In the estimate (30), we have assumed a slip ratio of one and that all thickness changes arise from ice dynamics rather than snow accumulation (see Appendix B); removing any contributions from snow accumulation or assuming a smaller slip ratio would decrease the magnitude of the off-lake pressure estimates. We find that these estimates are at most only a few kilopascals in magnitude (Table 1), which is consistent with our results and underlying assumptions.

To invert the elevation-change data, we require the ice thickness ![]() ${\bar{H}}$, ice viscosity

${\bar{H}}$, ice viscosity ![]() ${\eta}$, basal drag coefficient

${\eta}$, basal drag coefficient ![]() ${\beta}$ and horizontal ice velocity

${\beta}$ and horizontal ice velocity ![]() $\bar{\pmb{u}}$ that are associated with the background ice-flow state over the lakes (Fig. 1). We obtain horizontal surface velocity from the MEaSUREs Phase-Based Antarctic Ice Velocity Map (Version 1) (Mouginot and others, Reference Mouginot, Rignot and Scheuchl2019a; Reference Mouginot, Rignot and Scheuchl2019b) and ice thickness from MEaSUREs BedMachine Antarctica (Version 3) (Morlighem and others, Reference Morlighem2020; Morlighem, Reference Morlighem2022). The basal drag and ice viscosity are estimated with the Ice-sheet and Sea-level System Model (shelfy-stream approximation) by inverting the surface-velocity data (Morlighem and others, Reference Morlighem, Rignot, Seroussi, Larour, Ben Dhia and Aubry2010; Larour and others, Reference Larour, Seroussi, Morlighem and Rignot2012). The ice flow-law coefficient is estimated by providing the empirical relation from Cuffey and Paterson (Reference Cuffey and Paterson2010) (with a flow-law exponent of

$\bar{\pmb{u}}$ that are associated with the background ice-flow state over the lakes (Fig. 1). We obtain horizontal surface velocity from the MEaSUREs Phase-Based Antarctic Ice Velocity Map (Version 1) (Mouginot and others, Reference Mouginot, Rignot and Scheuchl2019a; Reference Mouginot, Rignot and Scheuchl2019b) and ice thickness from MEaSUREs BedMachine Antarctica (Version 3) (Morlighem and others, Reference Morlighem2020; Morlighem, Reference Morlighem2022). The basal drag and ice viscosity are estimated with the Ice-sheet and Sea-level System Model (shelfy-stream approximation) by inverting the surface-velocity data (Morlighem and others, Reference Morlighem, Rignot, Seroussi, Larour, Ben Dhia and Aubry2010; Larour and others, Reference Larour, Seroussi, Morlighem and Rignot2012). The ice flow-law coefficient is estimated by providing the empirical relation from Cuffey and Paterson (Reference Cuffey and Paterson2010) (with a flow-law exponent of ![]() $n=3$) with an approximate depth-averaged temperature between the melting point and the surface temperature, which is obtained from the Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, version 2 (MERRA-2) climate reanalysis (Global Modeling and Assimilation Office (GMAO), 2015; Gelaro and others, Reference Gelaro2017). All ‘background’ values are obtained by averaging the data

$n=3$) with an approximate depth-averaged temperature between the melting point and the surface temperature, which is obtained from the Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, version 2 (MERRA-2) climate reanalysis (Global Modeling and Assimilation Office (GMAO), 2015; Gelaro and others, Reference Gelaro2017). All ‘background’ values are obtained by averaging the data ![]() $(\bar{H},\bar{\pmb{u}})$ and modelled variables

$(\bar{H},\bar{\pmb{u}})$ and modelled variables ![]() $(\eta,\beta)$ over a square region (60 km

$(\eta,\beta)$ over a square region (60 km ![]() $\times$ 60 km) surrounding the lake (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). Sources for all datasets and the code repository are provided in the ‘Data availability’ statement. Parameter values for each lake are reported in Table 1.

$\times$ 60 km) surrounding the lake (Stubblefield and others, Reference Stubblefield, Meyer, Siegfried, Sauthoff and Spiegelman2023a). Sources for all datasets and the code repository are provided in the ‘Data availability’ statement. Parameter values for each lake are reported in Table 1.

The Antarctic subglacial lakes that we explore here have been the subject of many previous studies: Mercer Subglacial Lake beneath the confluence of the Whillans Ice Stream and Mercer Ice Stream (Fricker and others, Reference Fricker, Scambos, Bindschadler and Padman2007; Fricker and Scambos, Reference Fricker and Scambos2009; Siegfried and others, Reference Siegfried, Fricker, Carter and Tulaczyk2016); Mac1 beneath MacAyeal Ice Stream (Fricker and others, Reference Fricker, Scambos, Carter, Davis, Haran and Joughin2010; Siegfried and Fricker, Reference Siegfried and Fricker2021); Byrds10 beneath Byrd Glacier (Smith and others, Reference Smith, Fricker, Joughin and Tulaczyk2009; Wright and others, Reference Wright2014); and Davids1 (sometimes referred to as D2) beneath David Glacier in East Antarctica (Smith and others, Reference Smith, Fricker, Joughin and Tulaczyk2009; Lindzey and others, Reference Lindzey2020; Malczyk and others, Reference Malczyk, Gourmelen, Werder, Wearing and Goldberg2023). These lakes cover a wide range of physical parameters arising from different ice flow regimes across East Antarctica and West Antarctica (Fig. 2). In particular, the lakes display a variety of combinations of the nondimensional parameters ![]() $\lambda$ and

$\lambda$ and ![]() $\gamma$ (Table 1). We first discuss the effective pressure estimates for each lake and then compare the behaviours between the lakes. Lake boundaries derived from elevation-change anomalies for these lakes are provided by Siegfried and Fricker (Reference Siegfried and Fricker2018); we compare the altimetry-derived boundaries to the spatial extent of the effective pressure estimates below. As noted in the description around Eqn. (20), the particular choice of the lake boundary does not substantially influence the calculated effective pressure but is of primary importance in deciding where the calculation is valid.

$\gamma$ (Table 1). We first discuss the effective pressure estimates for each lake and then compare the behaviours between the lakes. Lake boundaries derived from elevation-change anomalies for these lakes are provided by Siegfried and Fricker (Reference Siegfried and Fricker2018); we compare the altimetry-derived boundaries to the spatial extent of the effective pressure estimates below. As noted in the description around Eqn. (20), the particular choice of the lake boundary does not substantially influence the calculated effective pressure but is of primary importance in deciding where the calculation is valid.

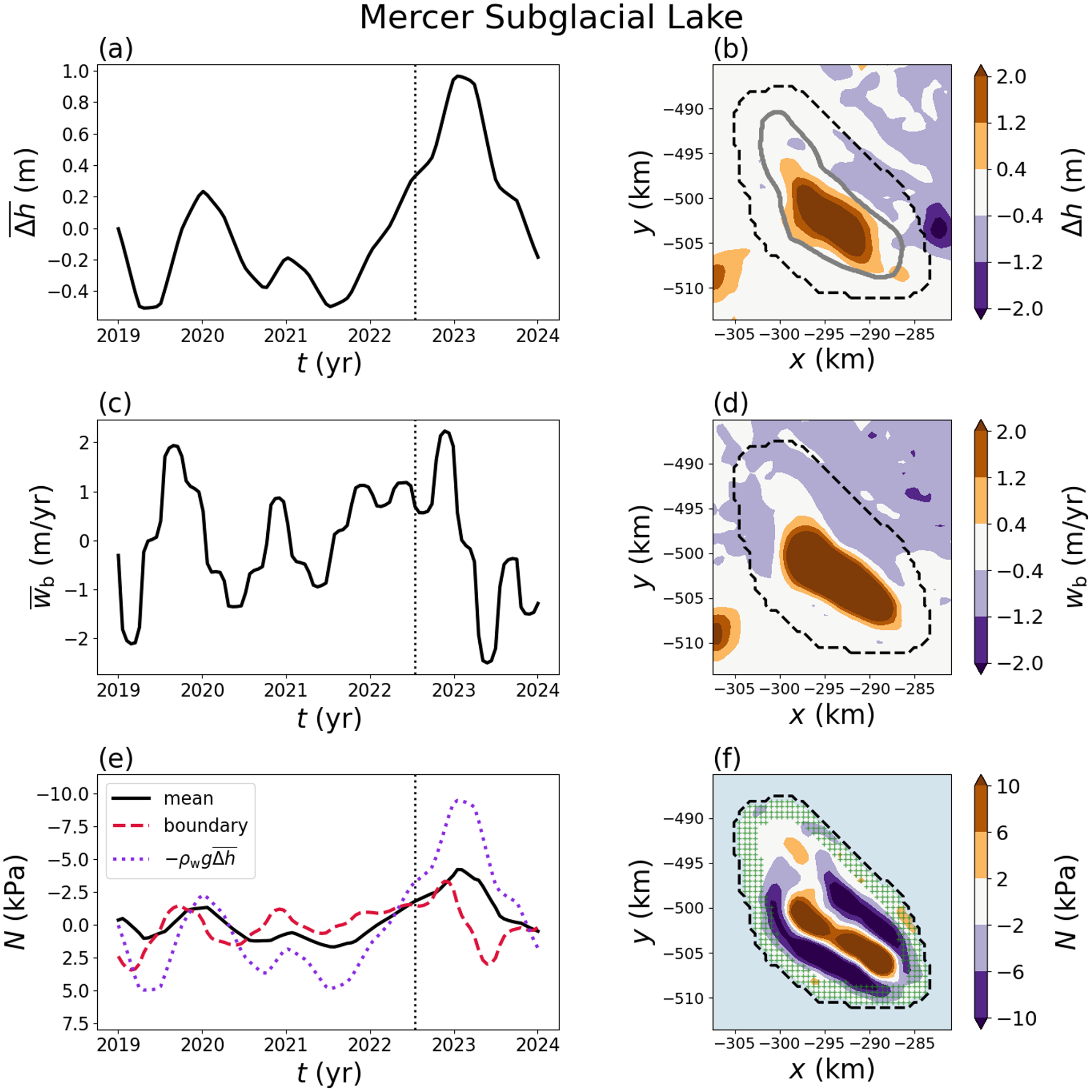

4.2. Mercer Subglacial Lake

Mercer Subglacial Lake (MSL) exists beneath an ice thickness of ![]() $H\approx 1$ km at the confluence of the Whillans Ice Stream and Mercer Ice Stream along the Siple Coast of West Antarctica (Fig. 2). MSL has filled and drained repeatedly since the beginning of the ICESat era (Fricker and others, Reference Fricker, Scambos, Bindschadler and Padman2007; Fricker and Scambos, Reference Fricker and Scambos2009; Siegfried and others, Reference Siegfried, Fricker, Carter and Tulaczyk2016; Siegfried and Fricker, Reference Siegfried and Fricker2018; Reference Siegfried and Fricker2021). The estimated ice viscosity (

$H\approx 1$ km at the confluence of the Whillans Ice Stream and Mercer Ice Stream along the Siple Coast of West Antarctica (Fig. 2). MSL has filled and drained repeatedly since the beginning of the ICESat era (Fricker and others, Reference Fricker, Scambos, Bindschadler and Padman2007; Fricker and Scambos, Reference Fricker and Scambos2009; Siegfried and others, Reference Siegfried, Fricker, Carter and Tulaczyk2016; Siegfried and Fricker, Reference Siegfried and Fricker2018; Reference Siegfried and Fricker2021). The estimated ice viscosity (![]() $\eta \approx 5\times 10^{14}$ Pa s) is an order of magnitude smaller than the East Antarctic lakes considered herein. The basal drag coefficient (

$\eta \approx 5\times 10^{14}$ Pa s) is an order of magnitude smaller than the East Antarctic lakes considered herein. The basal drag coefficient (![]() $\beta \approx 10^{10}$ Pa s m

$\beta \approx 10^{10}$ Pa s m![]() $^{-1}$) is slightly larger than Mac1, but the same order of magnitude or smaller than the East Antarctic lakes (Table 1).

$^{-1}$) is slightly larger than Mac1, but the same order of magnitude or smaller than the East Antarctic lakes (Table 1).

We estimate the effective pressure from the elevation-change anomaly and basal vertical velocity (Fig. 7). Since the beginning of the ICESat-2 period, the elevation-change data show that MSL completed a multi-peaked drainage event and has more recently begun to refill. The mean effective pressure in the lake, ![]() $\bar{N}$, was small but positive (up to

$\bar{N}$, was small but positive (up to ![]() $\sim$0.5 kPa) during the draining stage and has become negative during the filling stage as the ice column is lifted upwards (Fig. 7c). Maps of the elevation-change anomaly, basal vertical velocity and effective pressure during the filling stage highlight the spatial variability in the system (Fig. 7b,d,f). We find that the effective pressure has both regions of positive and negative effective pressure, which results from the combined influence of the basal vertical velocity and elevation change (Fig. 7f). In particular, the centre of the lake has a positive effective pressure that is surrounded by a ring of negative effective pressure that forms as the lake refills. The same type of ringed structure is found in the synthetic example (Fig. 5). We consider the possible consequences of this behaviour in the discussion. The altimetry-derived lake boundary from Siegfried and Fricker (Reference Siegfried and Fricker2018) closely corresponds to the spatial extent of the effective pressure anomaly over MSL.

$\sim$0.5 kPa) during the draining stage and has become negative during the filling stage as the ice column is lifted upwards (Fig. 7c). Maps of the elevation-change anomaly, basal vertical velocity and effective pressure during the filling stage highlight the spatial variability in the system (Fig. 7b,d,f). We find that the effective pressure has both regions of positive and negative effective pressure, which results from the combined influence of the basal vertical velocity and elevation change (Fig. 7f). In particular, the centre of the lake has a positive effective pressure that is surrounded by a ring of negative effective pressure that forms as the lake refills. The same type of ringed structure is found in the synthetic example (Fig. 5). We consider the possible consequences of this behaviour in the discussion. The altimetry-derived lake boundary from Siegfried and Fricker (Reference Siegfried and Fricker2018) closely corresponds to the spatial extent of the effective pressure anomaly over MSL.

Figure 7. Elevation change (![]() $\Delta h)$, basal vertical velocity inversion (

$\Delta h)$, basal vertical velocity inversion (![]() $w_\mathrm{b}$) and effective pressure (

$w_\mathrm{b}$) and effective pressure (![]() $N$) for Mercer Subglacial Lake. (a) Time series of the mean value of the elevation change over the lake. (b) Map–plane contour plot of the elevation change at the time shown by the vertical dashed line in (a). The dashed black line shows the boundary selected for calculating the effective pressure while the solid grey line shows the boundary from Siegfried and Fricker (Reference Siegfried and Fricker2018). (c) Time series of the mean basal vertical velocity and (d) map–plane plot at the time shown by the vertical dashed line. (e) Time series of the mean effective pressure (solid), effective pressure within 2 km of the boundary (long dashed) and the reference pressure

$N$) for Mercer Subglacial Lake. (a) Time series of the mean value of the elevation change over the lake. (b) Map–plane contour plot of the elevation change at the time shown by the vertical dashed line in (a). The dashed black line shows the boundary selected for calculating the effective pressure while the solid grey line shows the boundary from Siegfried and Fricker (Reference Siegfried and Fricker2018). (c) Time series of the mean basal vertical velocity and (d) map–plane plot at the time shown by the vertical dashed line. (e) Time series of the mean effective pressure (solid), effective pressure within 2 km of the boundary (long dashed) and the reference pressure ![]() $-\rho_\mathrm{w} g \overline{\Delta h}$ (short dashed). (f) Map–plane plot of the effective pressure. The green hatched region corresponds to the values used to estimate the effective pressure near the lake boundary.

$-\rho_\mathrm{w} g \overline{\Delta h}$ (short dashed). (f) Map–plane plot of the effective pressure. The green hatched region corresponds to the values used to estimate the effective pressure near the lake boundary.

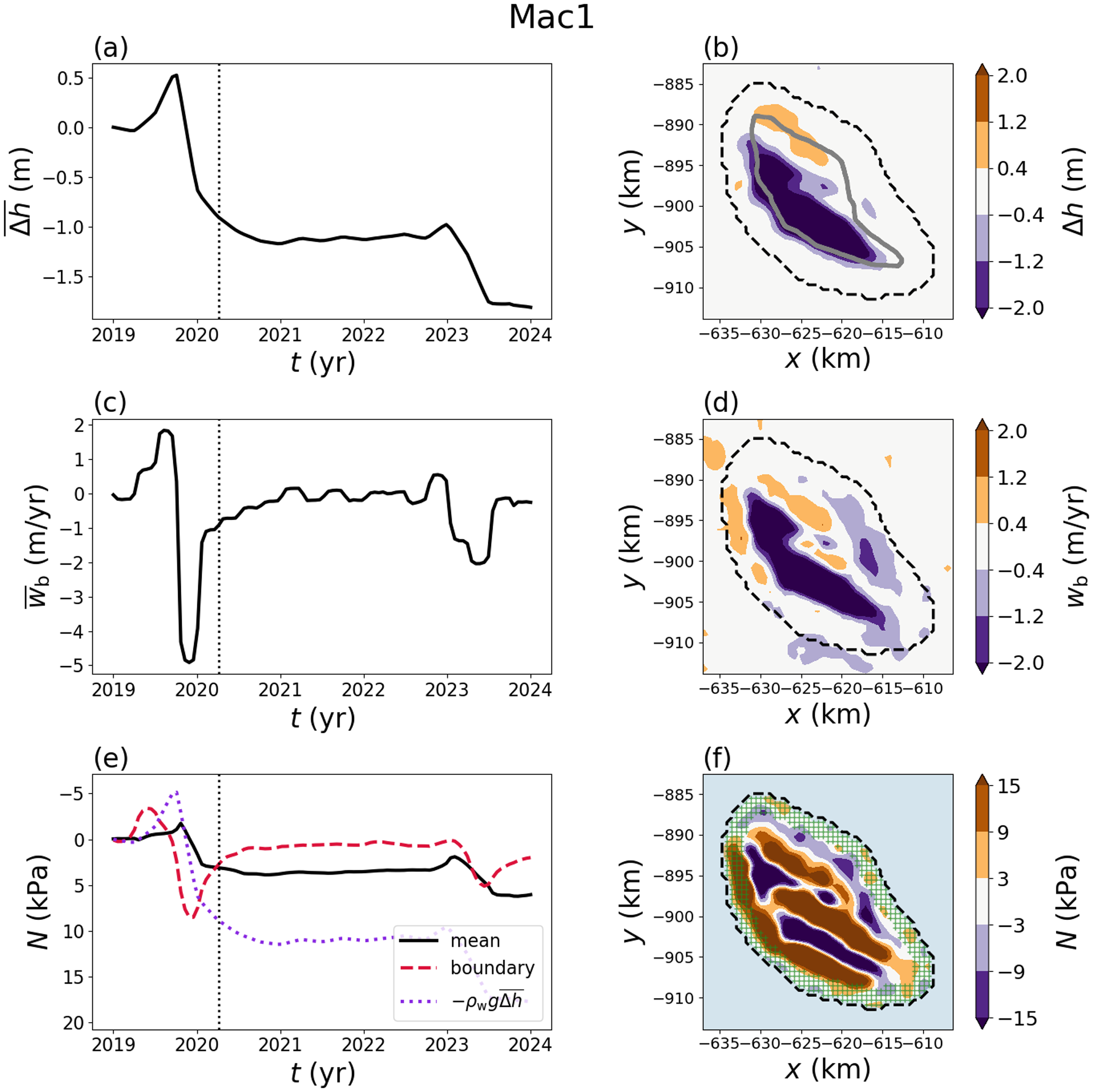

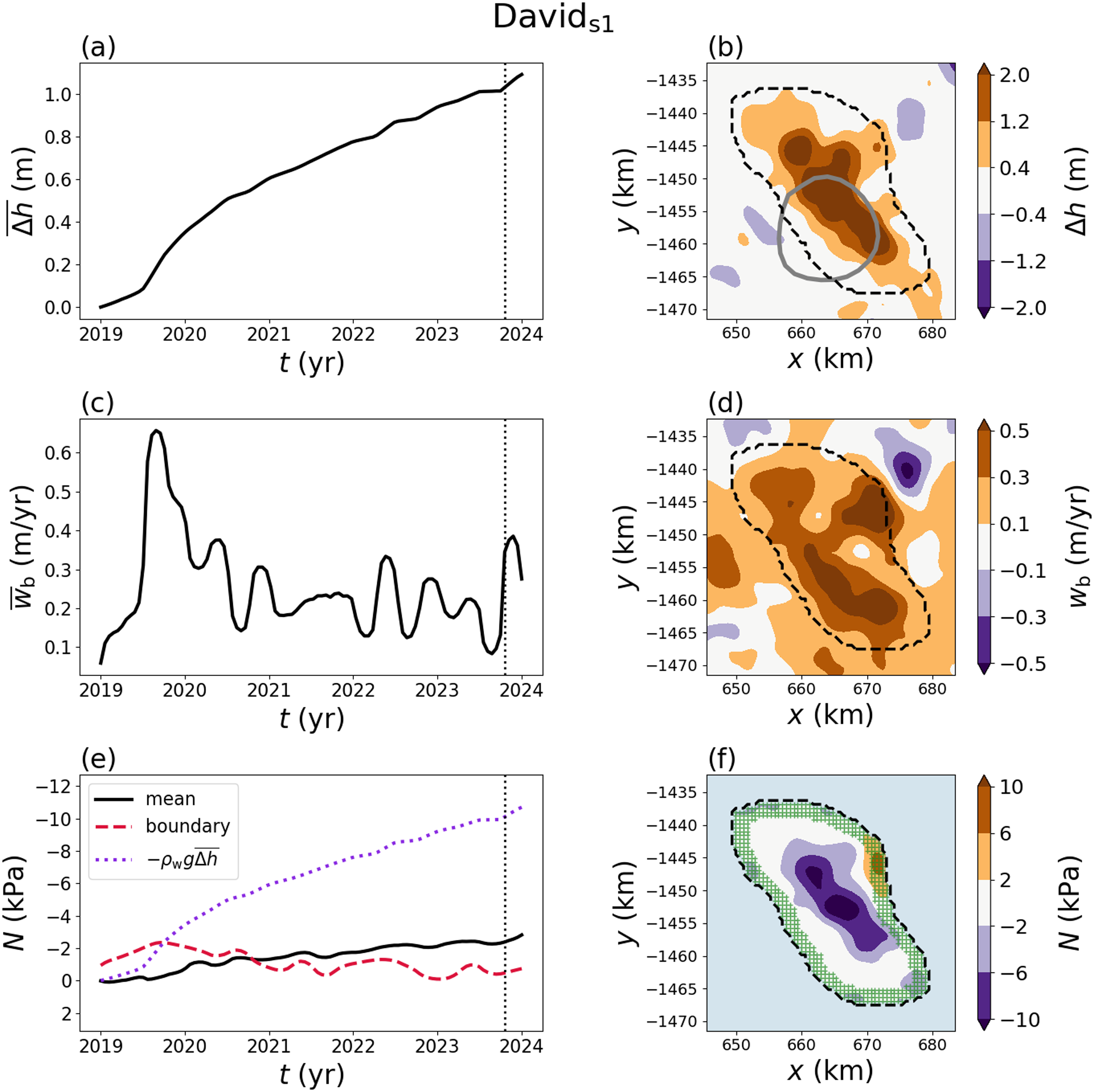

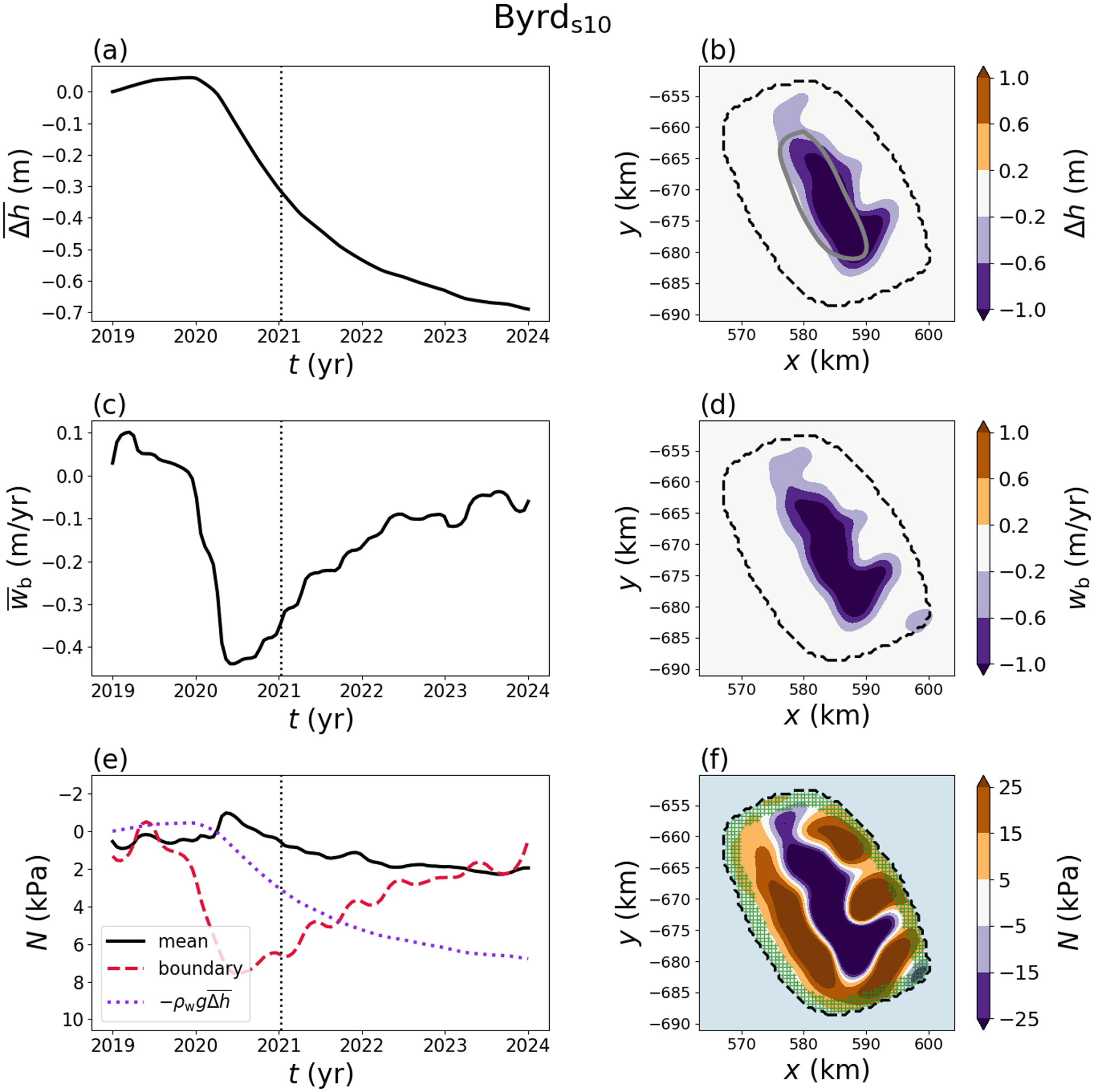

4.3. Mac1