Introduction

Political Science (PS) in Latin America has experienced significant institutional growth since the second half of the twentieth century. The growth has manifested as the expansion of graduate and undergraduate programs, increased research funding availability, the establishment of national and regional political science associations, and growing academic publications and influence by local scholars. Within the subfield of comparative politics (CP), particularly concerning academic production, a heated debate has emerged between two contrasting tendencies: North Americanization vs. parochialism. While some Latin American scholars actively seek to publish and engage with mainstream literature from the Global North, others primarily concentrate their research on their home countries (Tanaka Reference Tanaka2017; Freidenberg Reference Freidenberg2017; Codato et al. Reference Codato, Madeira and Bittencourt2020; Lucca Reference Lucca2021). Footnote 1

Scholarship on PS’s institutionalization in the region has predominantly concentrated on case study research, examining countries such as Brazil, Argentina, El Salvador, Chile, Ecuador, Costa Rica, Uruguay, and Mexico, among others (Amorim and Santos Reference Amorim Neto and Santos2015; Calvo et al. Reference Calvo, Elverdín, Kessler and Victoria Murillo2019; Artiga-González Reference Artiga-González2006; Fuentes and Santana Reference Fuentes and Santana2005; Heiss Reference Heiss2015; Mejía Acosta et al. Reference Mejía Acosta, Freidenberg and Pachano2005; Alfaro Redondo and Cullel Reference Alfaro Redondo and Cullell2005; Barrientos del Monte Reference Barrientos Del Monte2015; Buquet Reference Buquet2012). Footnote 2 Notably, this scholarship often lacks a systematic comparative component, making it difficult to draw generalizable conclusions about the institutionalization process mentioned above. Furthermore, these studies have yet to explore a previously overlooked dimension of institutionalization: doctoral students’ training in comparative politics within Latin American universities.

The CP subfield in Latin America holds significant importance, making notable contributions to mainstream Global North political science literature (Munck Reference Munck2007). Most Latin American political scientists specialize in comparative politics (Freidenberg and Malamud Reference Freidenberg and Malamud2017). Since the 1990s, numerous young political scientists from Latin America have pursued academic training in the United States (Freidenberg and Malamud Reference Freidenberg and Malamud2013; Bulcourf and Cardozo Reference Bulcourf and Cardozo2017). However, with the growth of the discipline and graduate programs in the region, many students are opting for local training in Latin America in addition to those studying abroad. These changes in the region’s institutional educational landscape raise important questions about the nature of CP training received by graduate students. Do future Latin American comparative politics scholars receive similar training? Is there a single canon for instructing CP in the region?

To investigate PhD students’ training systematically, we built an original dataset of the comparative politics readings Footnote 3 that they encounter in 21 universities across nine Latin American countries. These universities offer courses in comparative politics within their political science doctoral programs. In total, our dataset comprises 1886 individual readings—our unit of analysis is a reading. This dataset facilitated a network analysis to determine the existence of a unified canon for teaching CP in Latin American doctoral programs. Additionally, we employed descriptive statistics to gain deeper insights into various reading characteristics (including reading type, outlet, methodology, language, and authors’ gender and region of origin), shedding light on the nature of the canon being imparted in these programs.

Among various reading characteristics, we devoted special attention to the type of readings to assess the presence of the tension between North Americanization and parochialism within PhD-level CP materials. Mainstream readings are those published in Scopus-indexed outlets. Footnote 4 Scopus-indexed publications undergo rigorous peer review and must engage with substantive comparative literature. They employ widely accepted theoretical and methodological frameworks within the discipline to contribute to academic knowledge. Therefore, regardless of whether these readings examine one or multiple cases, we classify them as mainstream. Typical examples include articles from prestigious US-based journals like the American Political Science Review or Comparative Political Studies, as well as publications from leading European book publishers such as Oxford or Cambridge University Press. Footnote 5

In contrast, parochial readings focus exclusively on their respective Latin American universities’ home countries. We categorized readings as parochial if they were not published in Scopus-indexed sources and solely concentrated on the country where the university is located.

Not all readings neatly fit into the categories of mainstream or parochial, though. We have identified a distinct third category, which we conceptualize as regional readings. Unlike mainstream materials, these readings do not engage in explicit dialogue with the established Global North literature and, as a result, are not indexed in Scopus database outlets. However, unlike parochial materials, regional readings extend beyond a university’s home country. Instead, they involve cross-case comparisons to contribute to academic knowledge within the discipline. Books or chapters published by the Fondo de Cultura Económica in Mexico or the Instituto de Estudios Peruanos in Peru, along with articles in Argentine journals like Revista POSTData or Desarrollo Económico, are frequently used as regional sources.

Our findings challenge the conventional dichotomy of North Americanization versus parochialism underscored by previous scholarship, offering a more nuanced interpretation within the context of doctoral curricula in CP. Across the region’s graduate programs, we have identified a reasonably unified canon for the teaching of comparative politics. While acknowledging some curriculum variations among universities, our analysis reveals a predominantly centralized network structure. This centralization can be attributed to the widespread inclusion of mainstream CP readings, primarily originating from the Global North, and shared by most universities.

Contrary to expectations set by existing literature, universities almost entirely exclude parochial materials from their curricula. Instead, they favor the inclusion of regional readings that embrace a comparative approach, often sourced from Latin American journals. This finding challenges the ongoing debate regarding the tension between parochialism and North Americanization, which fails to recognize the presence of regional readings. However, these readings are not consistently shared among universities. Consequently, unlike mainstream content, doctoral students in Latin America are not consistently exposed to similar regional materials. While most PhD students in Latin America engage with mainstream CP works by scholars like Gary W. Cox and Adam Przeworski, they typically do not consume similar materials originating from the region.

The article is organized as follows. Section two provides an overview of political science’s institutionalization in Latin America, focusing on comparative politics and the North Americanization versus parochialism debate. Section three details our data collection process and methods for investigating the presence of a unified canon for teaching comparative politics in the region. Section four presents our network analysis results, followed by section five, which offers descriptive statistics for a deeper understanding of the network. The last section summarizes the main findings, discusses their implications, and suggests future research directions.

Comparative Politics Institutionalization in Latin America: Between Autonomy and Northern Influence

From its origins in the mid-twentieth century to the present day, political science in Latin America has undergone a process of institutionalization, gradually consolidating as an independent field of study. This process, which entails the discipline’s transition from a vocation to a profession (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2015; Tanaka Reference Tanaka2017), has been studied through different dimensions, such as academic offerings at the undergraduate and graduate levels, regional journals’ publication impact, and the development of scientific and professional networks, among others (Durán-Martínez et al. Reference Durán-Martínez, Sierra and Snyder2023; D’Alessandro Reference D’Alessandro2013; Bulcourf Reference Bulcourf2012; Altman Reference Altman2012; Bulcourf and Cardozo Reference Bulcourf and Cardozo2017).

Historically, the development of PS in Latin America has had a solid link to democratization processes (Barrientos del Monte Reference Barrientos Del Monte2013; Ravecca Reference Ravecca2019). During the 1970s, the discipline experienced a “golden age,” cut short by the re-emergence of authoritarian regimes (Altman Reference Altman2006). However, with the return of democracy in the 1980s–1990s, PS’s institutionalization resumed its trajectory in the region. This resurgence was driven by scholars’ interest in understanding democratic transitions and changes in the international context following the end of the Cold War (Barrientos del Monte Reference Barrientos Del Monte2013). For instance, prior to democracy’s “third wave” (Huntington Reference Huntington1991), Latin American students interested in politics had to study law or sociology due to the lack of academic offerings in PS (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2015; Tanaka Reference Tanaka2017). The relatively recent establishment of undergraduate and graduate programs in universities across the region reflects the increasing trend in institutionalization (Tanaka and Dargent Reference Tanaka and Dargent2015; Altman Reference Altman2012).

While political science’s institutionalization has made significant progress in Latin America, there is still considerable variation among countries in the region. This variation can be attributed to divergent historical contexts and academic politics (Altman Reference Altman2006; Bulcourf and Cardozo Reference Bulcourf and Cardozo2017; Amorim Neto and Santos Reference Amorim Neto and Santos2015). In some countries, the establishment of bachelor’s degree programs in PS is relatively recent; in others, there exists a wide array of master’s and doctoral programs. Footnote 6 The level of institutionalization ranges from countries with well-established national political science associations and universities offering a broad spectrum of degrees and research programs, such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Uruguay, and, to a lesser extent, Colombia, Costa Rica, and Venezuela. In contrast, some countries like Bolivia lack these attributes (Varnoux Garay Reference Varnoux Garay2005; Barrientos del Monte Reference Barrientos Del Monte2013; Freidenberg Reference Freidenberg2017).

The growing institutionalization of PS is also evident in the academic production from and about the region. Notably, the subdiscipline of Latin American comparative politics has historically made significant contributions to the Global North’s “mainstream” literature in political science (Munck Reference Munck2007). The institutionalization of PS in Latin America has provided intellectuals with the necessary research infrastructure to “give voice” to a distinctive Latin American perspective when examining political phenomena. Guillermo O’Donnell’s work (Reference O’Donnell1973, Reference O’Donnell, Schmitter and Whitehead1986, Reference O’Donnell1993, Reference O’Donnell1994) stands out as a prime example of this phenomenon.

Scholars have underscored a tension between two extremes in Latin American comparative politics academic production: North Americanization vs. parochialism (Tanaka Reference Tanaka2017; Lucca Reference Lucca2021). While some Latin American scholarship has significantly influenced (and been influenced by) the Anglo-Saxon “mainstream” literature in PS, not all academic work on the region engages with this body of scholarship (Munck Reference Munck2007; Freidenberg Reference Freidenberg2017). Some Latin American researchers, especially younger scholars who have studied abroad, actively seek publication in US or European academic journals and dialogue with the mainstream literature from the Global North. However, many Latin America-based scholars tend to focus their research on their own countries (Lucca Reference Lucca2021; Chasquetti Reference Chasquetti2010; Rocha Reference Rocha2012), resulting in the formation of parochial scientific communities (Tanaka Reference Tanaka2017; Codato et al. Reference Codato, Madeira and Bittencourt2020). Traditionally, research projects in each country primarily center on national (or sub-national) cases; therefore, comparative political analyses involving multiple Latin American countries remain relatively scarce (Rocha Reference Rocha2012; Chasquetti Reference Chasquetti2017; Basabe-Serrano and Huertas-Hernandez Reference Basabe-Serrano and Huertas-Hernandez2018).

The North Americanization of CP in Latin America is rooted in the origins of the subfield, which has been intrinsically connected to developments in the Global North, particularly in the United States and continental Europe (Munck Reference Munck2007; Calvo et al. Reference Calvo, Elverdín, Kessler and Victoria Murillo2019). Global North scholars have historically influenced the work of Latin American social scientists (Munck and Snyder Reference Munck and Snyder2019). Footnote 7 Driven by both greater financial resources and intellectual curiosity in the study of Latin America than their Western European counterparts, US universities have attracted many young Latin American political scientists since the 1990s who pursued advanced academic training in the United States (Bulcourf and Cardozo Reference Bulcourf and Cardozo2017). Within PS, most of these academics have specialized in comparative politics. While some have opted to build their professional or academic careers in the United States, many have returned to Latin America after completing their PhD studies (Freidenberg and Malamud Reference Freidenberg and Malamud2013). Footnote 8 Upon their return, Latin American comparative politics naturally absorbed some of the themes, methods, and research design strategies predominating in the North (Bulcourf and Cardozo Reference Bulcourf and Cardozo2017). These migration processes have bolstered the transnational networks of scholars, both formal and informal, between the South and the North (Munck and Snyder Reference Munck and Snyder2019). Footnote 9

Nonetheless, Northern influences have not uniformly impacted all scientific communities across Latin America. As articulated by Weyland (Reference Weyland2015, 128), compared to other regions, “there is much less of a clear-cut separation between politics and political science in Latin America.” For example, changes in government or regime transitions can redefine leadership roles within universities, thus affecting their intellectual pursuits and research initiatives (Munck and Snyder Reference Munck and Snyder2019). Consequently, the distinct socio-political contexts in each country have given rise to a fragmented landscape within the field of PS, characterized by varying levels of institutionalization and diverse research agendas (Barrientos del Monte Reference Barrientos Del Monte2013). A clear manifestation of this fragmentation is a parochialism of academic production, whereby research programs predominantly confine their focus to domestic cases (Codato et al. Reference Codato, Madeira and Bittencourt2020).

In sum, while part of Latin American CP directly converses with the Global North scholarship to analyze political phenomena, other research programs focus primarily on their respective home countries. This dichotomy has resulted in a noticeable tension often referred to as “North Americanization versus parochialism” (Tanaka Reference Tanaka2017; Freidenberg Reference Freidenberg2017; Codato et al. Reference Codato, Madeira and Bittencourt2020; Lucca Reference Lucca2021). Given the active involvement of Latin American-based scholars in training graduate students in the region, this article explores whether this tension is mirrored in the curricula of PhD programs.

Data and Methods

To investigate the training of doctoral students, we constructed an original dataset encompassing the assigned readings in CP at 21 universities across nine Latin American countries. This dataset facilitated a network analysis, revealing the connections between universities based on their assigned readings. Our dataset includes various dimensions of these readings, such as author information (region of origin and gender) and reading details (type, outlet, method, and language), all of which we utilize to characterize the resultant network. In total, we collected data for 1886 readings, with each reading serving as our unit of analysis.

We conducted an extensive online search to identify universities potentially offering a PhD program in PS. Subsequently, we emailed these universities to gather the necessary information for constructing our dataset. Footnote 10 Specifically, we contacted the political science departments Footnote 11 —reaching out to doctoral program directors and coordinators—and requested the reading list for the comprehensive exam in comparative politics. Footnote 12 When that exam was not part of the doctoral program, we asked for syllabi for the core or general seminar on comparative politics. When that type of seminar was not offered either, we asked for syllabi for two or three seminars covering essential topics in comparative politics. In all instances, we requested the most updated version of the materials. Footnote 13

We collected data for 21 universities spanning nine Latin American countries, including six from Argentina, Footnote 14 four from Brazil, Footnote 15 three from Colombia, Footnote 16 two from Chile, Footnote 17 two from Mexico, Footnote 18 one from Uruguay, Footnote 19 one from Peru, Footnote 20 one from Ecuador, Footnote 21 and one from Venezuela Footnote 22 (see Table A.1 in the Appendix for the specific university departments, graduate programs, and consulted materials). Our sample of universities may present certain biases. For example, Argentine universities are overrepresented, while Mexican universities are underrepresented. Moreover, it is plausible that universities with more substantial financial resources were more responsive to our emails, likely due to having more administrative personnel available for public inquiries. Nonetheless, our sample includes both public and private universities from a diverse range of countries, making it sufficiently large and varied to draw generalizable conclusions about the state of comparative politics doctoral education across Latin America. Footnote 23

Based on our novel dataset, we conducted a network analysis to explore the similarities and differences in CP content provided by Latin American universities to their doctoral students. Our primary goal was to assess whether a unified model for training future comparativist scholars exists in Latin America. Graphically, each node represents a university, and connecting lines indicate shared readings between two or more universities. This analysis visually represents each university’s position within the broader network, reflecting the extent of shared readings.

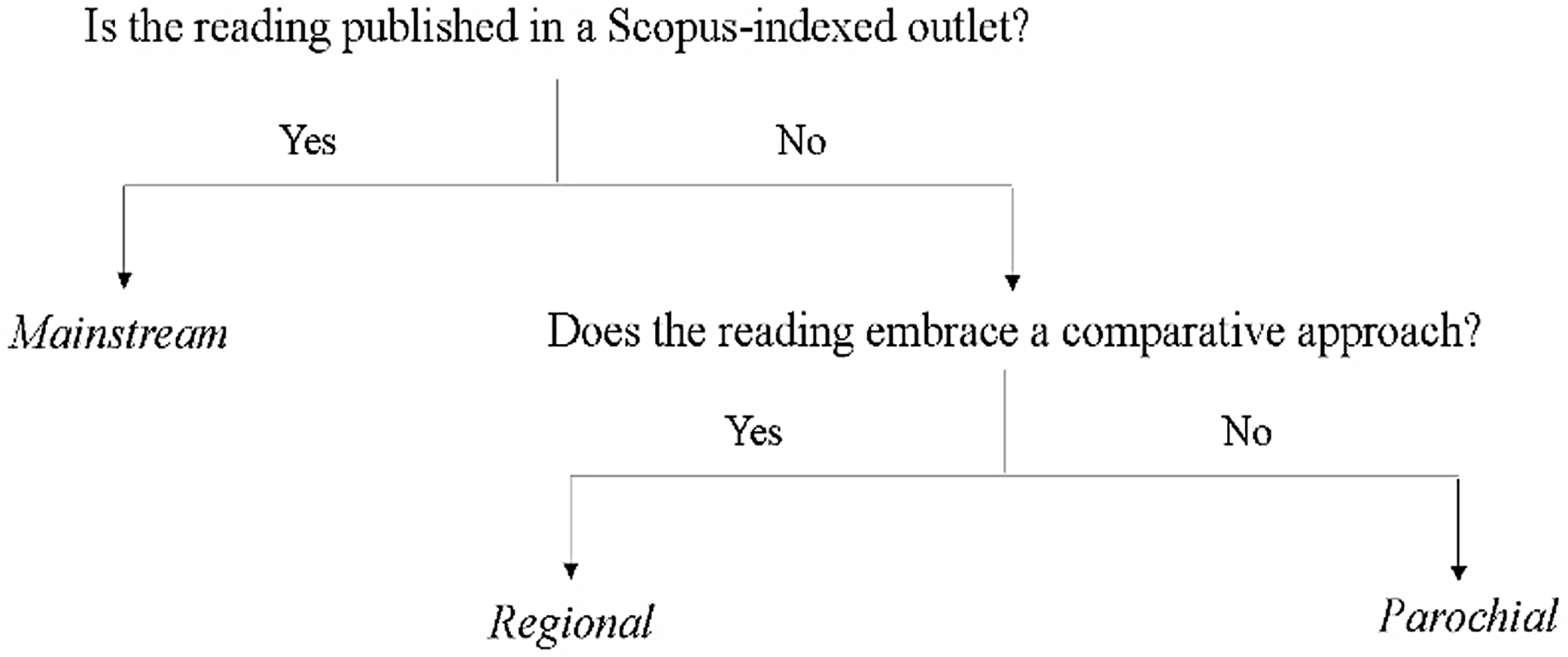

To evaluate whether the tension between North Americanization and parochialism is reflected in PhD program curricula, we categorized assigned readings into three types: mainstream, regional, and parochial. This categorization stems from the intersection of two analytical criteria. First, we determine if the reading is published in a Scopus-indexed outlet. Second, if the reading is not published in a Scopus outlet, we then assess whether it employs a comparative approach. Figure 1 illustrates our approach for categorizing these various types of readings.

Figure 1. Operationalization of Reading Types.

Source: Own elaboration.

We operationalized readings as mainstream if they were published in outlets (journals, books, etc.) indexed in Scopus, a widely recognized database for scholarly research. Scopus-indexed publications undergo rigorous peer review, ensuring a high standard of excellence. Therefore, we consider readings published in Scopus-indexed outlets as mainstream because they are likely to engage with the most relevant theoretical debates in the discipline to meet the criteria of excellence. In essence, regardless of whether these readings examine one or multiple cases, they are inherently in dialogue with the comparative literature on the topic, which we deem sufficient for classification as mainstream. For example, consider a recent book by Pérez Bentancur, Piñeiro, and Rosenblatt (Reference Pérez Bentancur, Piñeiro and Rosenblatt2020) that studies Uruguay’s Frente Amplio. While this book centers on the Uruguayan case, we classified it as mainstream because it was published in a Scopus-listed outlet (Cambridge University Press). Furthermore, it references other cases and directly engages with the comparative scholarship on the topic.

We operationalized readings as regional if they were not published in Scopus-indexed outlets but did employ a comparative approach when studying political phenomena. This categorization highlights a previously overlooked middle ground within the tension discussed in the literature. Although “mainstream” and “parochial” are relevant categories, they do not encompass the whole universe of assigned materials in CP within Latin American universities. The “regional” category helps address this gap by acknowledging materials that take a comparative perspective but do not meet the criteria for mainstream classification.

Finally, we operationalized readings as parochial if they were not published in Scopus-indexed outlets and exclusively focused on the home country of the university. Both conditions are individually necessary and jointly sufficient for classifying a reading as parochial. This rigorous operationalization strategy ensures that all designated parochial readings genuinely exhibit parochial tendencies. While the absence of a Scopus listing initially indicated that these readings may not be in dialogue with other cases through established scholarship, the additional criterion of being case studies about the same country as the assigning university confirms their parochial nature.

Latin American Graduate Training in Comparative Politics: A Unified Canon?

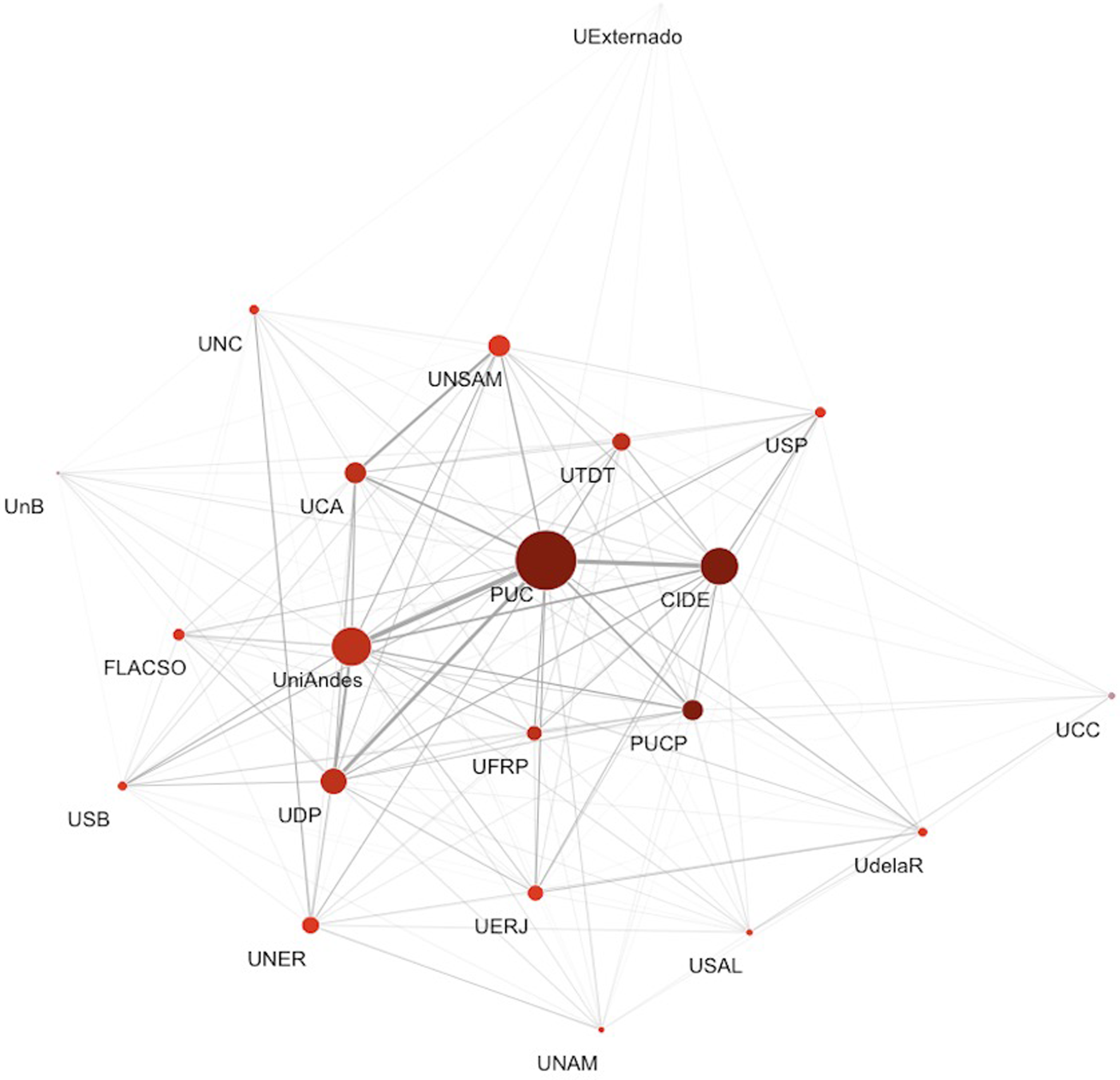

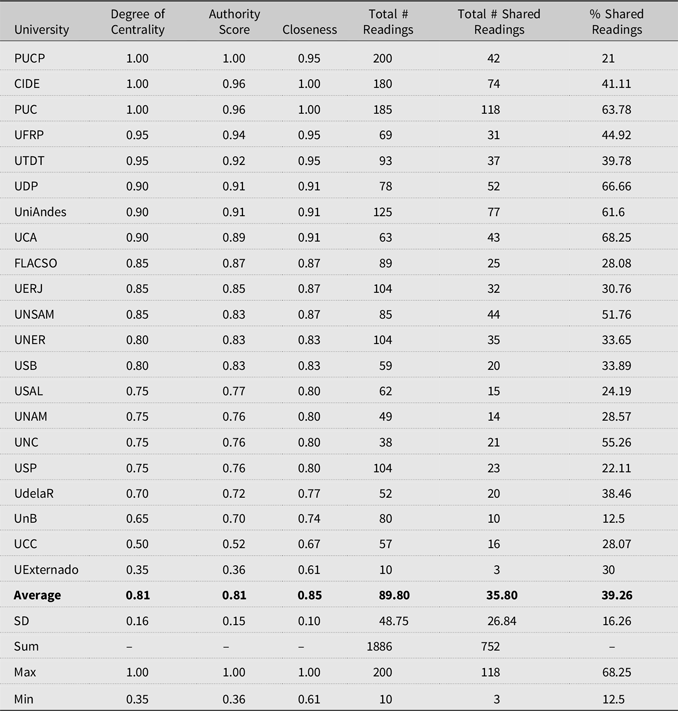

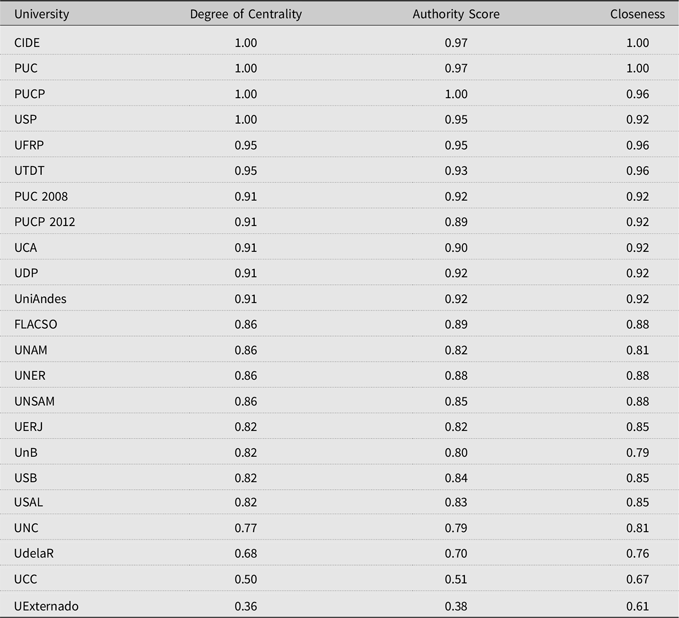

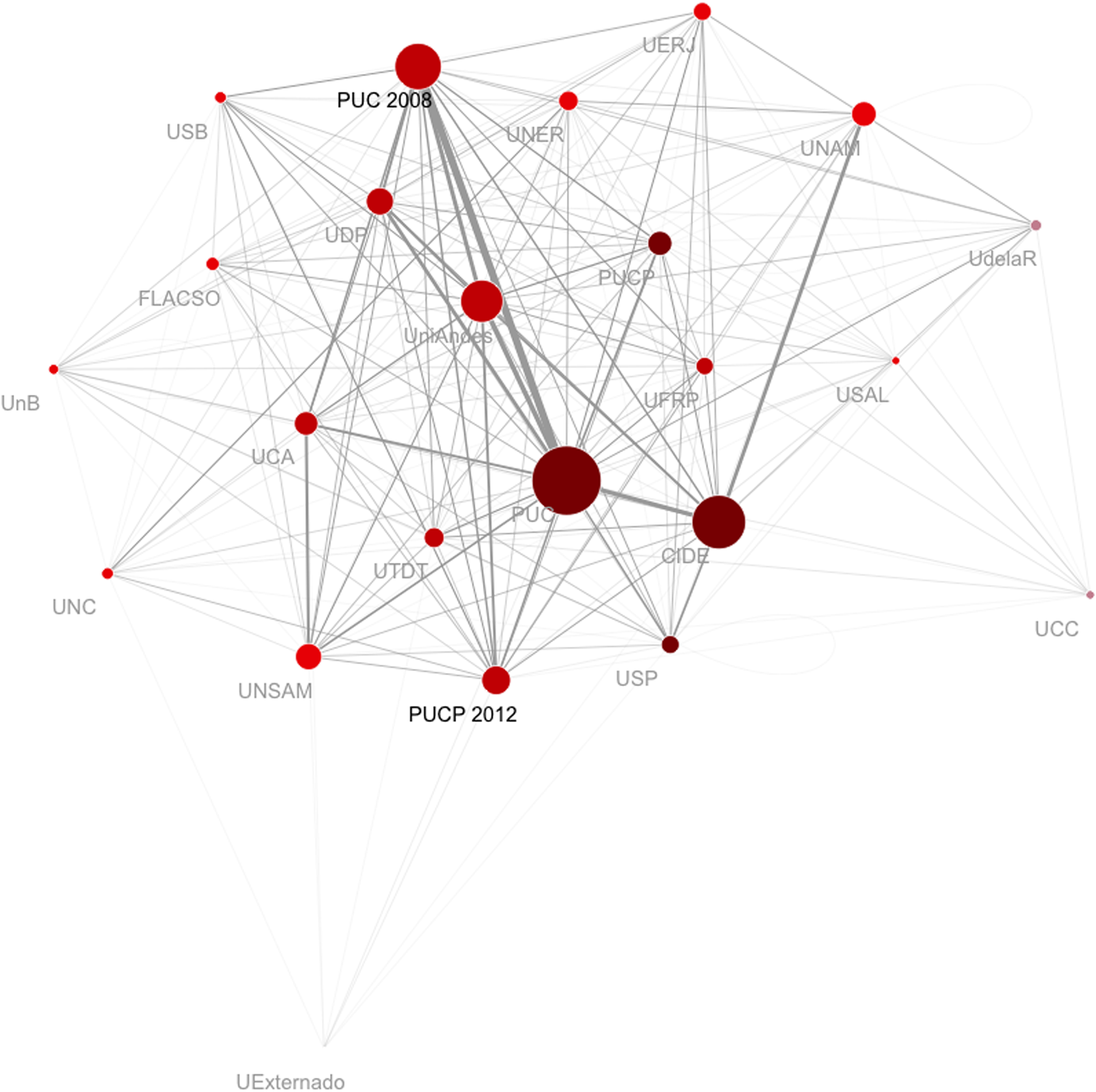

Figure 2 presents our network analysis’ results, with nodes representing universities and lines indicating shared readings. Footnote 24 The analysis reveals a reasonably centralized structure (Borgatti et al. Reference Borgatti, Ajay Mehra and Labianca2009), suggesting a well-defined center formed by PUCP, CIDE, and PUC, around which the rest of the universities tend to converge—except for the UExternado, which stands apart. A subgroup of universities (UFRP, UTDT, UDP, UCA, and UniAndes) is positioned closer to the center of the network. The remaining universities are dispersed further from one another and from the central cluster. However, they still surround the center, forming a third (FLACSO, UERJ, UNSAM, UNER, USB, USAL, UNAM, UNC, USP) and fourth (UdelaR, UnB, UCC) layer of a concentric circle. In summary, all universities in the network are clustered around the three most central institutions (PUCP, CIDE, and PUC).

Figure 2. Latin American Universities’ Connections across Comparative Politics Readings.

Source: Own elaboration.

Conceptually, the prominence of each university relies on its position and size within the network (Alonso and Carabali Reference Alonso and Carabali2019). These two indicators are crucial for assessing whether the canon is unified or not. The degree of centrality—the most widely used indicator in network analysis (Borgatti et al. Reference Borgatti, Ajay Mehra and Labianca2009)—gauges the total number of readings shared by “university X” with the other more central universities, determining each university’s position within the network. Footnote 25 A higher centrality value, standardized on a scale from 0 to 1, indicates a more central position within the network. Footnote 26 With a degree of centrality of 1, the PUCP, CIDE, and PUC are the network’s three most central universities, followed closely by a subgroup of five universities with a degree of centrality equal to or higher than 0.9 (UFRP, UTDT, UDP, UCA, and UniAndes). Footnote 27 As the shade of red becomes lighter in the figure, the universities’ degree of centrality decreases.

The size of each node reflects the total number of readings a university has in common with any other university. For instance, the PUC’s node is the biggest because, in total, it shares the greatest number of readings with other universities (118 readings). Footnote 28 In contrast, universities like UnB or UNAM are represented by tiny nodes because they barely share readings with other universities (respectively, they only share 10 and 14 readings with others).

It is worth noting that a higher degree of centrality for a university does not necessarily imply a larger node size. Put differently, a higher degree of centrality indicates that a university shares more readings with the more central universities of the network—not with any other university. The PUCP is an excellent example of this phenomenon. While it has a degree of centrality of 1, the highest possible value, its node size is relatively small. This is because it shares many readings with the other central universities in the network (e.g., PUC and CIDE) but only a few with more peripheral universities. A counterexample would be the UniAndes, which shares a great proportion of readings with other universities (hence, its node is large), but has relatively fewer readings in common with the network’s most prominent universities (hence, it is not at the center of the network).

In sum, our network analysis reveals a fairly cohesive model for instructing CP in the region, evident from the centralized arrangement of universities in the visualization. The next section will further evaluate the network’s underlying characteristics, devoting special attention to the types of readings incorporated and shared by universities to assess whether the North Americanization versus parochialism tension manifests in CP PhD curricula.

Reading Types’ Impact on Network Structure: Mainstream Dominance, Regional Engagement, and Scarce Parochialism

Universities present three possible types of readings: mainstream, regional, or parochial. Mainstream readings belong to the well-established canon of comparative politics, indicated by their inclusion in outlets indexed in Scopus. Regional readings are not published in Scopus-indexed outlets but offer a comparative approach when studying political phenomena. Parochial readings are neither published in Scopus-indexed outlets nor engaged in comparative analysis—they are exclusively focused on their home countries.

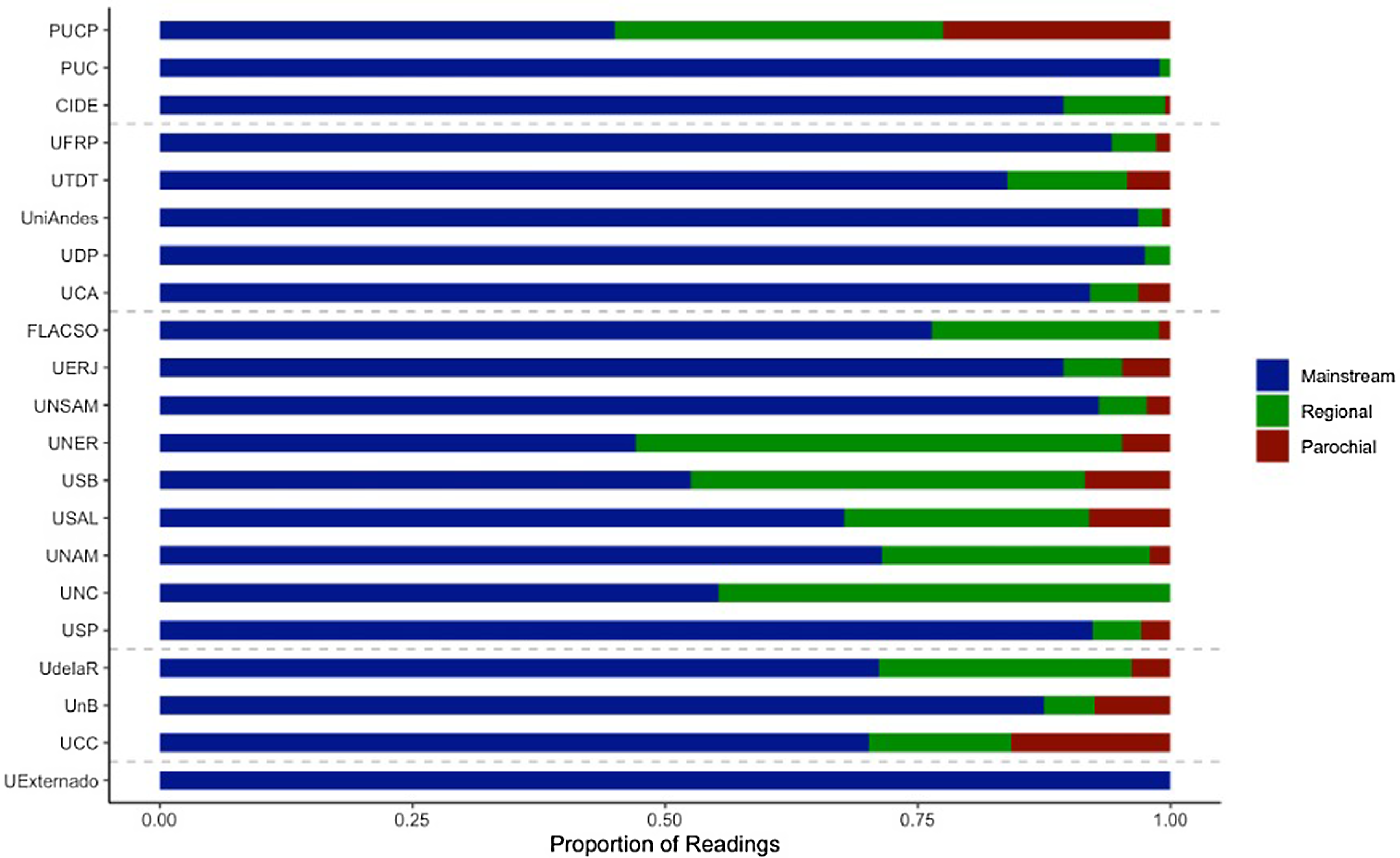

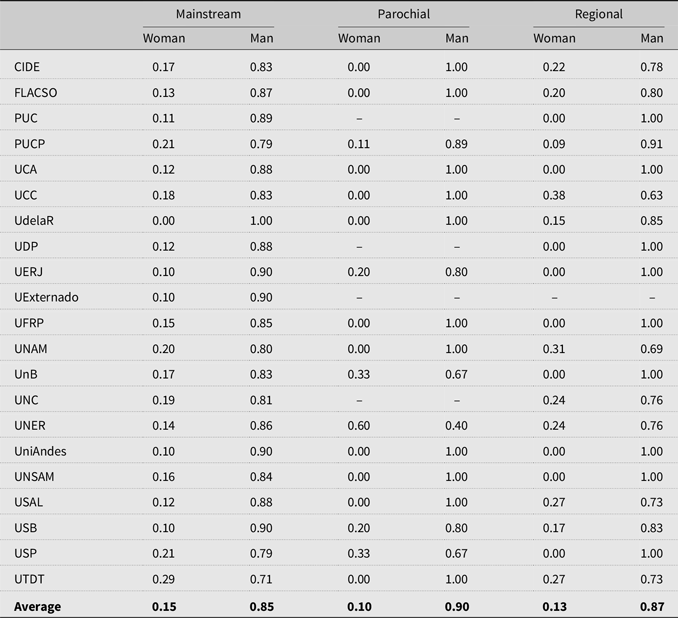

Figure 3 shows the proportion of different types of readings per university, organized by the most to the least central universities in the network.

Figure 3. Types of Readings per University.

Source: Own elaboration.

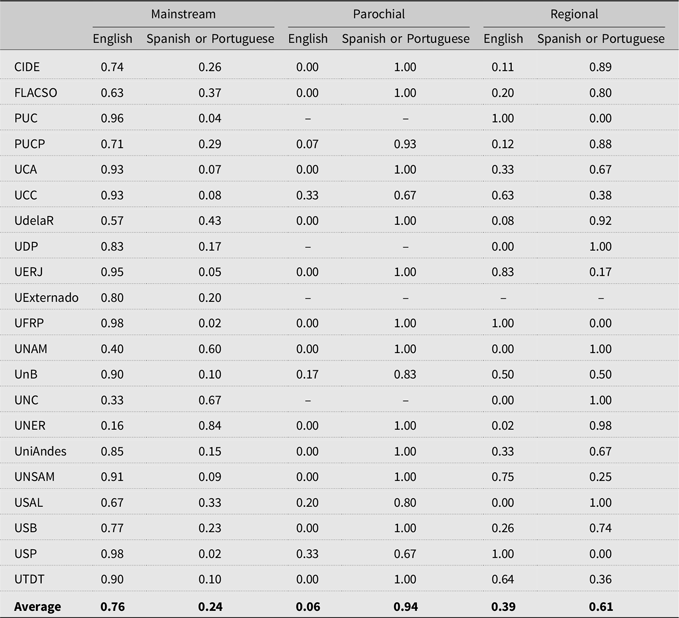

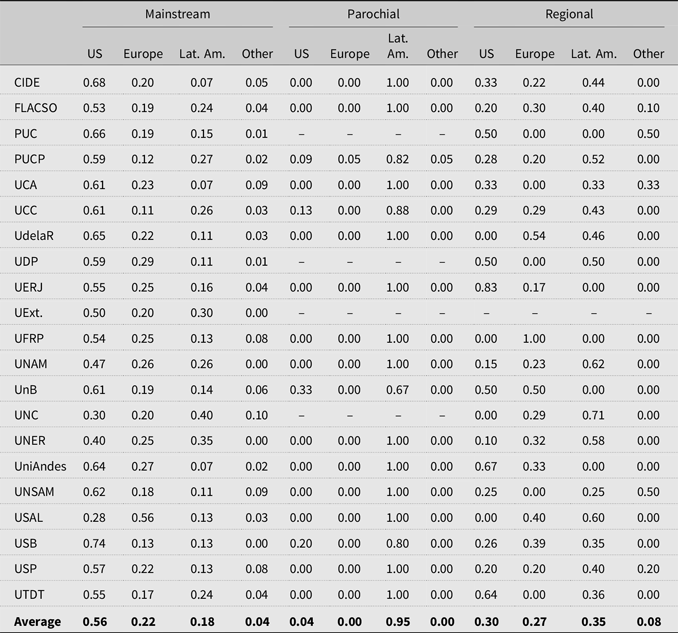

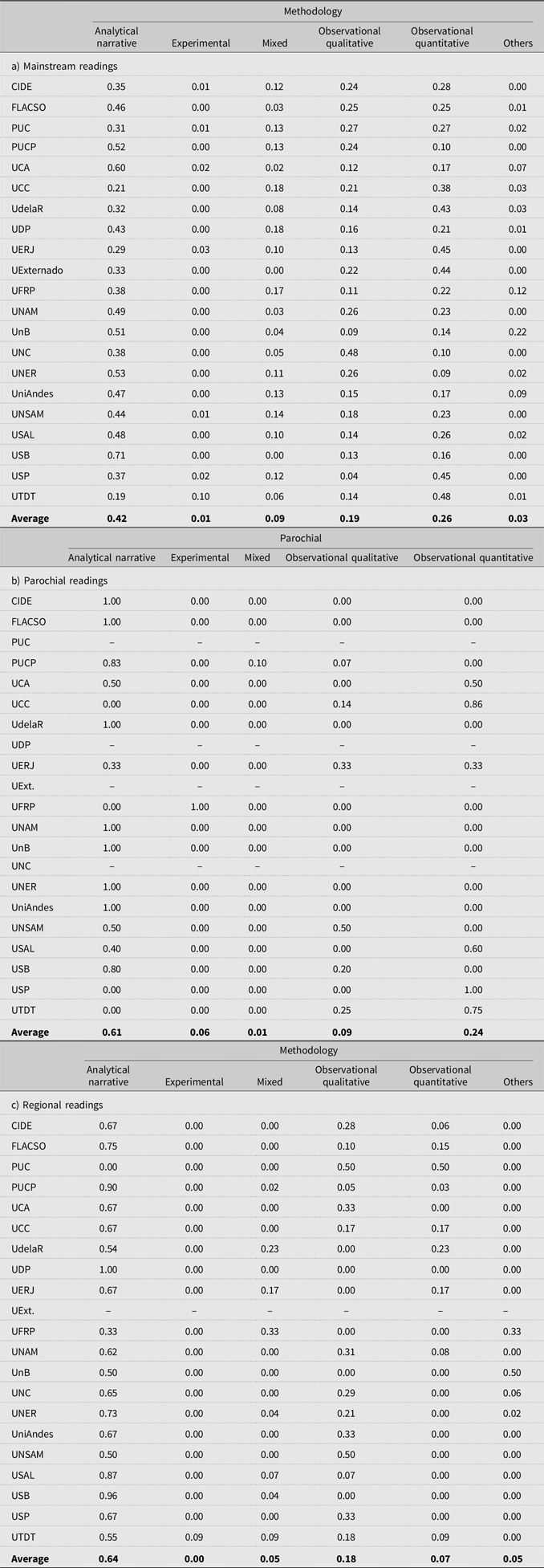

Most of the comparative politics readings offered in the region are mainstream (80%). The vast majority of universities focus their curricula on mainstream content, with 19 out of 21 universities in our sample offering over 50% of mainstream readings. Mainstream readings are predominantly authored in English (76%) by scholars from the Global North (78%). Footnote 29 The most common outlets for mainstream materials are Cambridge University Press for full books or selected book chapters (∼24%) and the American Political Science Review for journal articles (∼4%). Footnote 30 Their primary methodology is analytical narrative (42%), Footnote 31 followed by observational quantitative (26%) and qualitative (19%) methods. Footnote 32 Moreover, 85% of mainstream authors are men. Footnote 33 As we move further away from the central universities in the network, the proportion of mainstream readings decreases.

Contrary to expectations from the literature, only 5% of the offered materials, on average, are parochial. Parochial readings are the least commonly offered type of readings by all universities, both central and peripheral, thus demonstrating a consistent pattern of low parochialism across all institutions in the network. Unlike mainstream content, parochial readings are overwhelmingly produced in Spanish or Portuguese (94%) by Latin American scholars (95%). Like mainstream content, analytical narrative remains the primary research method (61%), followed by observational quantitative (24%) and qualitative (9%) methods. Again, men are the predominant authors, accounting for 90% of parochial materials. Siglo XXI Editores from Mexico and Editorial Alianza from Spain each account for approximately 5% of parochial publications, making them the most common outlets for this type of material. Footnote 34

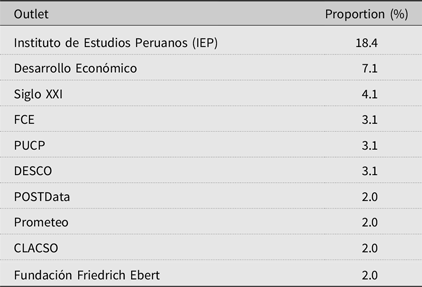

Instead of exclusively studying their home countries through parochial materials, universities are more inclined to incorporate readings that facilitate cross-case comparisons from regional journals. These types of readings—which we refer to as regional—represent, on average, 15% of the total proportion of readings. These materials are typically published in regional sources such as the Instituto de Estudios Peruanos (Fondo Editorial), comprising approximately 18% of them, or Desarrollo Económico from Argentina, accounting for around 7%. Footnote 35 The proportion of regional readings in university curricula increases as we move away from the center of the network, where mainstream readings tend to be more prevalent. Footnote 36 Put differently, regional readings are most common among peripheral vis-à-vis central universities. Footnote 37 While they are also predominantly authored by men (87%) and heavily rely on analytical narrative (64%), they offer a more mixed picture than mainstream and parochial readings in other relevant dimensions. For instance, they rely more on qualitative (18%) than quantitative (7%) methods. Footnote 38 Moreover, they are neither overwhelmingly written in Spanish/Portuguese (61%) nor English (39%), and their authors are almost evenly distributed from the United States (30%), Europe (27%), and Latin America (35%).

So far, we have uncovered two main findings. First, our network analysis reveals notable centralization within the network structure. Second, universities offer distinct types of readings, primarily mainstream, with a non-trivial proportion of regional materials and a negligible amount of parochial content. Now, the question arises: are these two outcomes interconnected? In other words, does the sharing of specific types of readings among universities significantly influence the overall network structure?

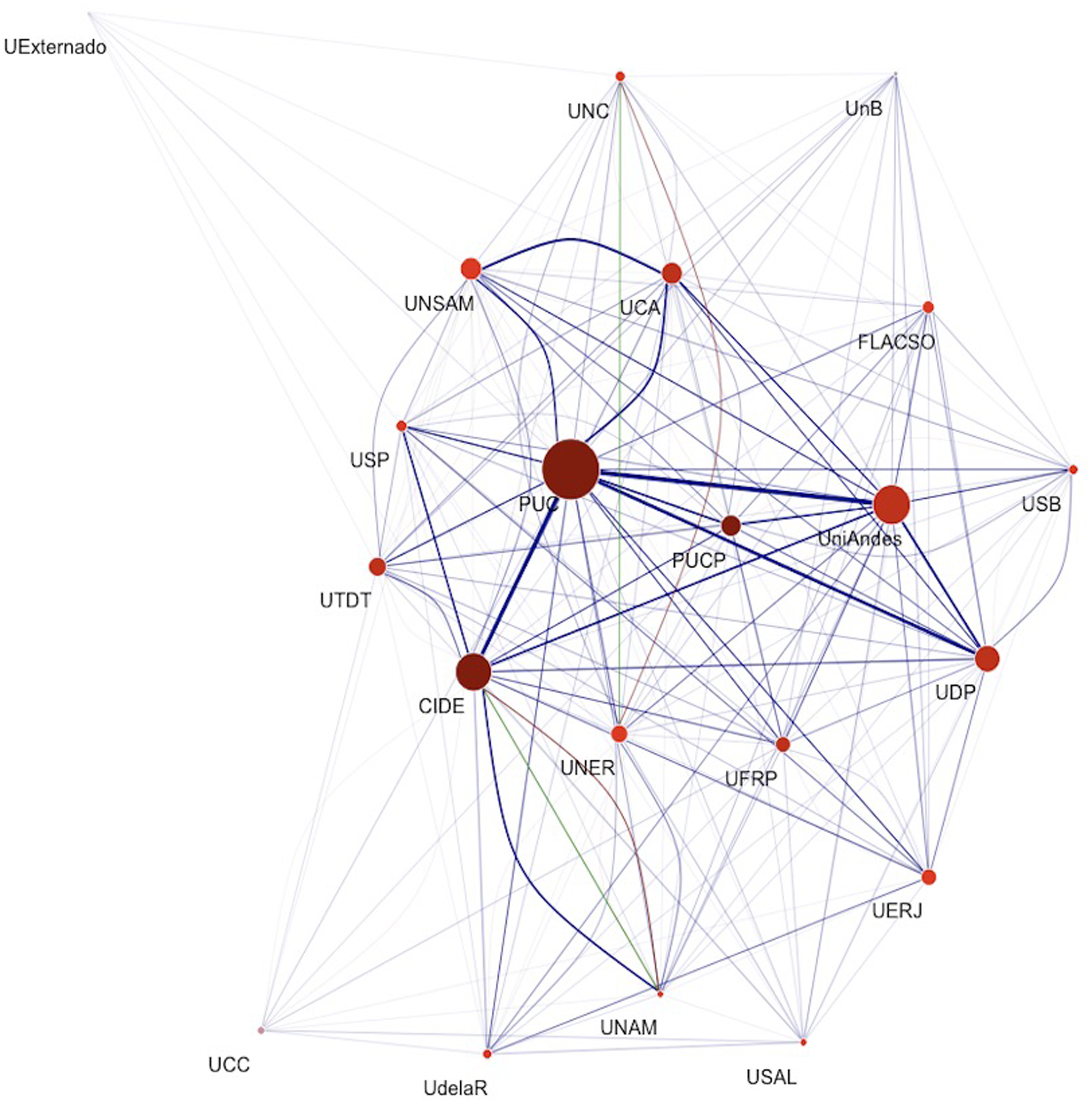

Figure 4 shows the connections between universities based on the type of shared reading. Mainstream readings are represented by blue lines, regional readings by green lines, and parochial readings by red lines. The thicker the line in the visualization, the greater the interconnections between universities. Notably, the figure displays a prevalence of mainstream literature connecting the universities, evident in the abundance of blue lines. In contrast, the network exhibits limited sharing of regional readings, indicated by the sparse green lines, and even scarcer sharing of parochial readings, with virtually no red lines in the visualization.

Figure 4. Latin American Universities’ Connections per Type of CP Reading.

Source: Own elaboration.

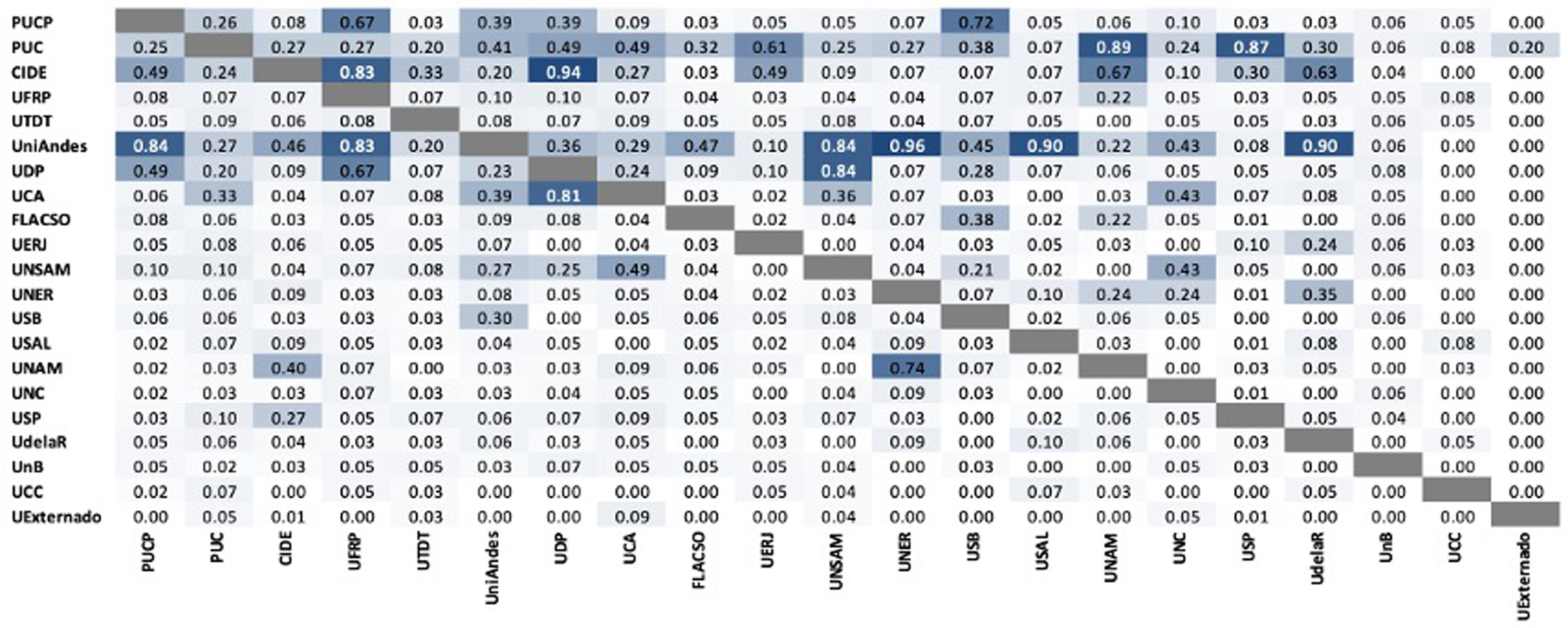

Figure 5 zooms into specific connections between all universities regarding shared mainstream readings. This heatmap employs varying shades of blue to represent the intensity of mainstream readings shared between pairs of universities. Deeper blue indicates higher overlap. Numbers within each dyad range from 0 to 1; 0 indicates no shared mainstream readings, while 1 denotes complete overlap. More central universities in the network (e.g., CIDE, UniAndes, and PUC) share a significant number of mainstream materials, as indicated by the prevalence of darkest shades of blue in the upper part of the heatmap. These connections are the key to the network’s centralized and reasonably cohesive structure. In contrast, peripheral universities (e.g., UdelaR or UnB) tend to have less overlap in their mainstream curricula, evidenced by the prevalence of lighter shades of blue in the lower portion of the heatmap. Importantly, all universities share at least one mainstream reading with another university. Footnote 39

Figure 5. Shared Mainstream Readings across Universities.

Source: Own elaboration.

The cells or dyads should be interpreted as the proportion of shared readings of a university in the Y-axis over a university in X-axis. For example, take the dyad on column 1, row 6 (cell value: 0.84). That means that the UniAndes shares 0.84 of its mainstream materials with the PUCP, over the PUCP’s total mainstream materials. The same interpretation criterion applies to the upcoming heatmaps, Figures 6 and 7.

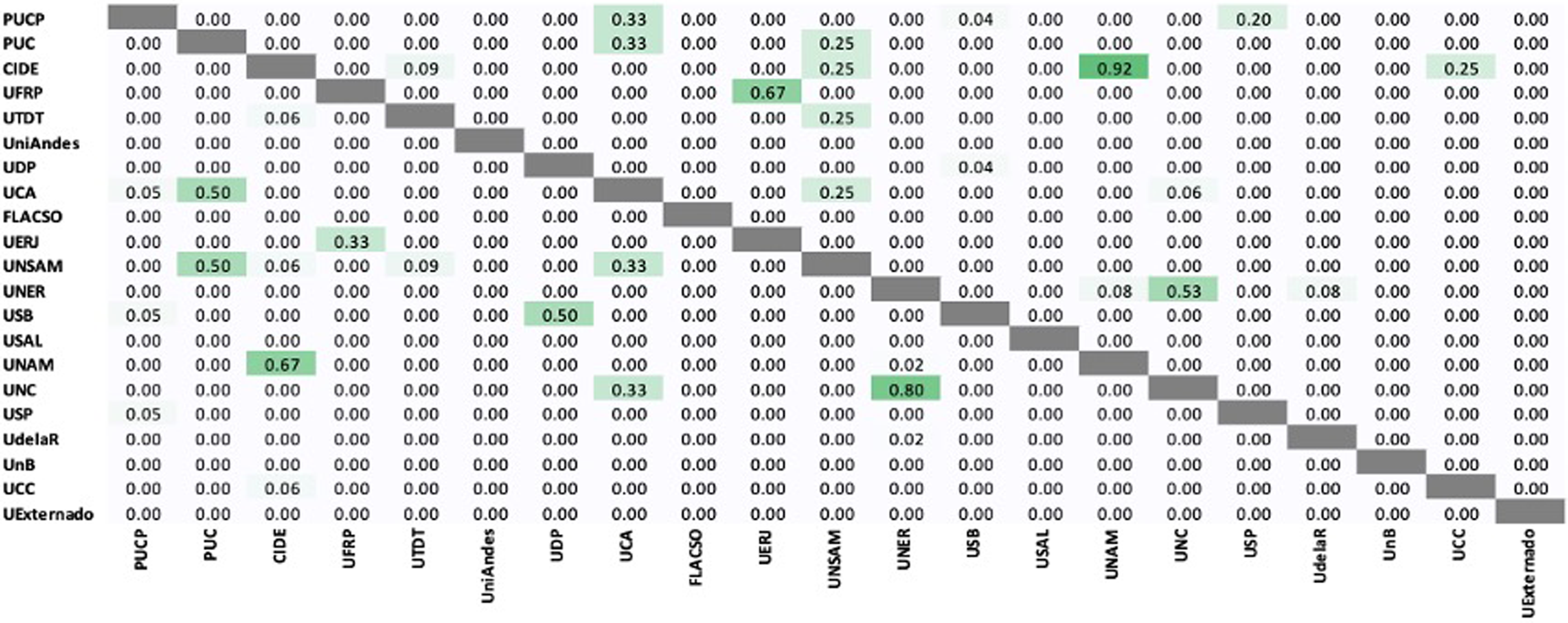

Figure 6. Shared Regional Readings across Universities.

Source: Own elaboration.

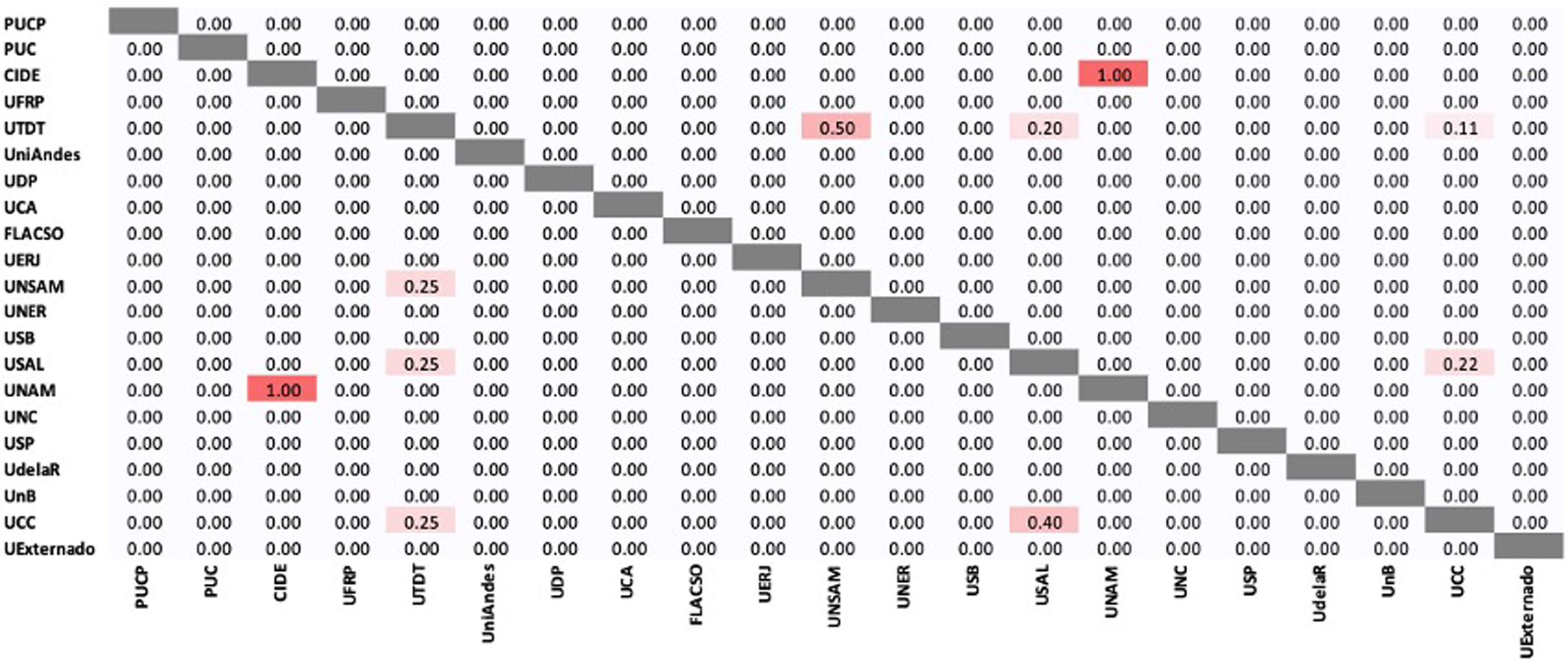

Figure 7. Shared Parochial Readings across Universities.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 6 reveals that, unlike mainstream content, regional readings are infrequently shared among universities, leading to a fragmentation of materials from Latin American sources. Put differently, this heatmap indicates that only a small proportion of regional readings are shared among a few universities, with no discernible clear or systematic pattern, as evidenced by the sparsely shaded green areas. Both central and peripheral universities in the network are occasionally connected in a seemingly random manner when it comes to regional content. Indeed, not even universities within the same country tend to share regional content, except for the two Mexican universities in our sample (CIDE and UNAM). These results suggest that future scholars encounter diverse materials from Latin America during their PhD studies.

Finally, Figure 7 illustrates the shared parochial readings among universities. The limited proportion of shared parochial readings is unsurprising, given their rarity in CP materials. Furthermore, parochial readings focus solely on a university’s home country, making them less likely to be shared with others. The heatmap shows only five pairs of universities sharing parochial materials, evident from the extremely few red areas. As expected, each pair comprises universities from the same country. Footnote 40

Discussion

This article represents the first comprehensive analysis of graduate-level comparative politics teaching in Latin America. To achieve this goal, we have compiled an original dataset consisting of comparative politics readings from 21 universities across nine Latin American countries. Our findings reveal a reasonably cohesive model for instructing comparative politics at the doctorate level in the region. Without neglecting relevant contrasts between universities, the network displays a clear centralized structure, indicating that most universities share a similar set of readings.

Our research contributes to an existing body of scholarship that emphasizes a central tension between North Americanization and parochialism in Latin American comparative politics (Tanaka Reference Tanaka2017; Freidenberg Reference Freidenberg2017; Codato et al. Reference Codato, Madeira and Bittencourt2020; Lucca Reference Lucca2021). Our network analysis, complemented by an examination of reading characteristics, offers a nuanced perspective on this ongoing debate within the literature. We found that the relatively uniform canon for teaching CP in the region’s graduate programs is explained by the inclusion of mainstream readings from the Global North, which are widely shared among universities. Contrary to expectations, our findings reveal that parochial content is nearly absent in these curricula.

Additionally, our findings challenge the aforementioned debate by highlighting the presence of an overlooked yet relevant category of academic content within university curricula: regional readings. These readings are typically drawn from regional sources and involve comparative analyses that extend beyond each university’s home country. Nevertheless, there is no consistent distribution of these regional readings among universities, as each institution tends to select its own set of such materials. As a result, doctoral students are not consistently exposed to similar CP readings originating from Latin America.

Is there a unified model of teaching comparative politics at the graduate level in the region, after all? In a broader sense, yes, as our network analysis has demonstrated. However, the more precise answer is both yes and no, depending on the type of readings under scrutiny. Yes, there is a unified model because emerging Latin American scholars receive similar mainstream training in comparative politics influenced by the Global North. And no, there is not a unified model because they consume diverse regional materials sourced from Latin American outlets. Essentially, while the mainstream canon imported from the Global North brings universities’ CP curricula closer together, the inclusion of regionally produced content sets them apart.

Drawing insights from Svampa (Reference Svampa2021), establishing a comparative politics canon rooted in Latin America could be pivotal in preventing the marginalization of regional academic production. To foster inter-country academic connections, the next step could involve establishing a uniform collection of regional readings shared across universities. By consolidating and disseminating a uniform selection of sound regional readings, Latin American comparative politics can maintain autonomy in the materials studied in graduate programs.

Rather than advocating a normative stance in favor of mainstream readings, we propose that integrating various types of readings could enrich the training of doctoral students in Latin America. Both parochial and regional readings offer distinct advantages for studying comparative politics in the region. For instance, they can provide a “dense knowledge” of cases, as highlighted by several scholars (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2015; Tanaka and Dargent Reference Tanaka and Dargent2015; Munck and Snyder Reference Munck and Snyder2019). Indeed, Global North scholars often utilize these materials to gain unique insights into the cases they study. While mainstream readings are essential for engaging PhD students with the core debates in the discipline, both regional and parochial materials are equally valuable for fostering the study of comparative politics from Latin America. This combination of assigned materials may help address the tension identified in the literature (Tanaka Reference Tanaka2017; Lucca Reference Lucca2021) between North-produced and localized academic knowledge.

Future research could assess an alternative operationalization strategy to classify the type of readings, addressing potential measurement biases. While Scopus is a widely accepted source, it might present certain publication biases, such as prioritizing English-speaking publications or not fully capturing research that provides “dense knowledge” of cases. Furthermore, to enhance our understanding of the topic, future research may expand the sample of universities studied to ideally encompass all comparative politics materials offered in Latin American PhD programs. Exploring the complete universe of CP materials would provide a more comprehensive view of doctoral students’ training in the region.

Additionally, investigating the evolution of CP curricula over time is a promising avenue of research. In this regard, we conducted an exploratory analysis of the evolution of the CP materials from two central universities in the network: PUC and PUCP. Footnote 41 We examined their materials from 2008 and 2012, respectively, to assess whether and how they have adapted and updated their curricula over the years. Footnote 42 Their past materials exhibit minimal changes compared to their current ones, indicating that both universities maintain central positions within the network when analyzing their older curricula. Footnote 43 Importantly, PhD programs in the region are relatively new, having emerged only in recent years, with no presence in the 1990s or early 2000s. Therefore, conducting a longitudinal analysis that could potentially reveal significant variations in the offered CP materials would require these programs to have been in place for a longer duration. Looking ahead, examining the evolution of the types of readings, together with their methodologies, language, and authorship, among other dimensions, would enrich our understanding of the discipline’s trajectory in the region.

Moreover, new research could delve into the professional and institutional profiles of universities. Such analyses could uncover potential relationships between universities’ institutional characteristics (such as professors’ training and country of origin, proportion of women in departments, and research funds availability) and their position within the network, as well as the types of readings offered.

Last but not least, future studies would benefit from cross-regional comparisons of graduate training in comparative politics. This approach could involve contrasting not only countries or regions within the Global South (e.g., Latin America with Africa or South Asia) but also between the Global South and the Global North (e.g., Latin America with the United States). Such comparisons could provide us with key insights into the academic training of future comparativists worldwide.

Acknowledgements

We thank Richard Snyder, Eva Rios, Rafael Piñeiro, and Tomas Dosek for their thoughtful and encouraging comments. We also thank Luciano Sigalov for his excellent research assistance. We are grateful to all the program directors and/or administrative staff who shared the requested materials for this paper with us.

Appendix

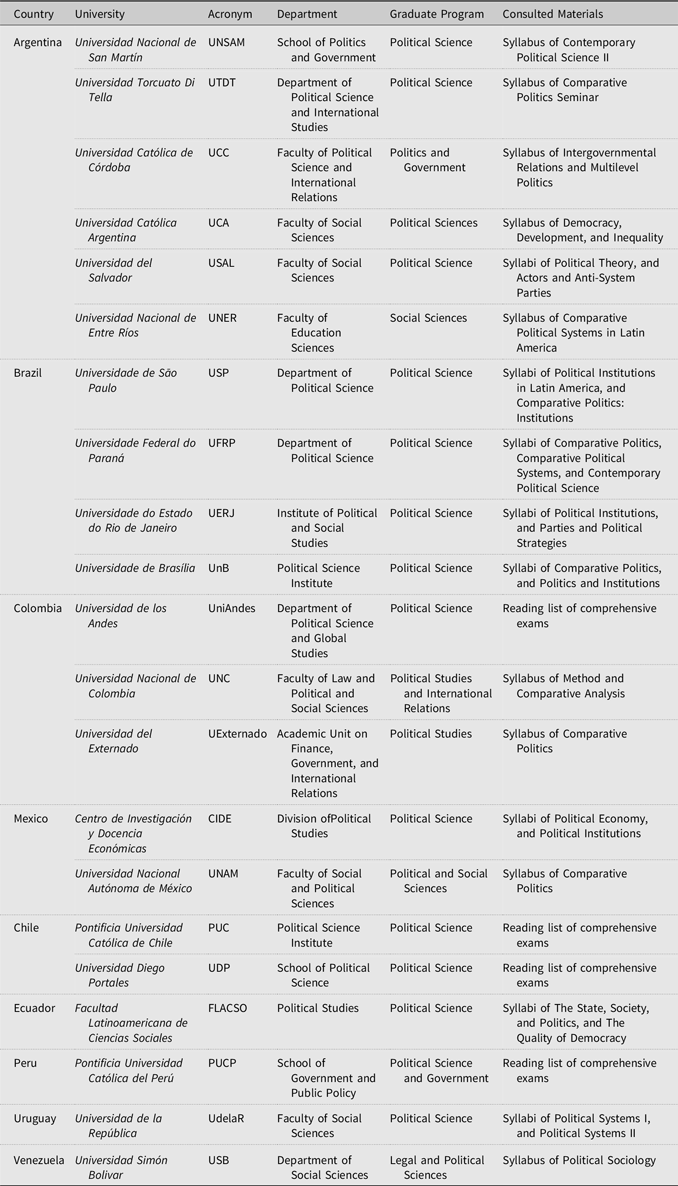

Table A1. Sample of Universities

Source: Own elaboration. The departments’ name, graduate program, and consulted materials translation from Spanish or Portuguese to English is ours.

Table A2. Latin American Universities’ Degree of Connectivity Measures

Source: Own elaboration.

Table A3. Language per Type of Reading

Source: Own elaboration.

Table A4. Authors’ Country of Origin per Type of Reading

Source: Own elaboration.

Table A5. Methodology per Type of Reading

Source: Own elaboration.

Table A6. Authors’ Gender per Type of Reading

Source: Own elaboration.

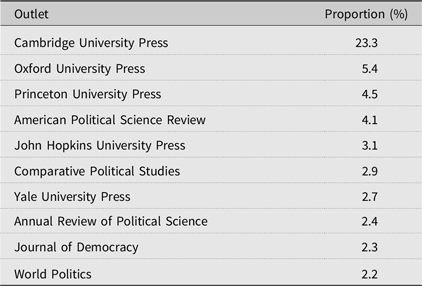

Table A7. List of Top Ten Outlets for Mainstream Readings

Source: Own elaboration.

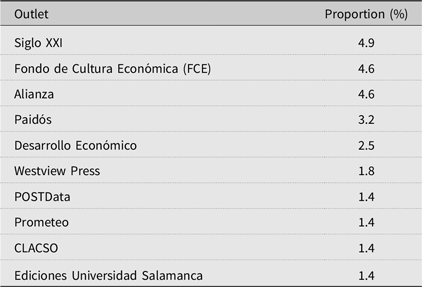

Table A8. List of Top 10 Outlets for Parochial Readings

Source: Own elaboration.

Table A9. List of Top Ten Outlets for Regional Readings

Source: Own elaboration.

Table A10. List of Top Ten Assigned Readings

Source: Own elaboration. When the reading was offered in different languages across universities, we counted it as the same text. For example, La Quiebra de las Democracias (count = 8) was offered six times in Spanish and two in English.

Table A11. Latin American Universities’ Degree of Connectivity Measures

Source: Own elaboration. The variation in the metrics of the PUC 2008 and PUCP 2012 compared to the PUC and PUCP (that is, their most recent materials) can be attributed mostly to the inclusion of newer readings by these universities since 2008 and 2012, respectively, rather than modifications to their old ones.

Figure A.1. Latin American Universities’ Connections across Comparative Politics Readings (including PUC 2008 and PUCP 2012).

Source: Own elaboration.