Insecure property rights pose barriers to economic activity and stifle growth across the developing world (Deininger and Goyal Reference Deininger and Goyal2024). The agricultural sector in sub-Saharan Africa employs 52% of workers, but insecure land tenure constricts agricultural investments and reduces productivity.Footnote 1 To alleviate these concerns, governments and international donors devote sizable resources to land tenure formalization programs. Land titles are available on-demand to many African farmers as part of “piecemeal” titling programs (Honig Reference Honig2022). Despite households’ incentives to title and the widespread availability of land titles, the uptake of formal property rights remains decidedly uneven. In Ethiopia, 79% of households possess such a title; in Burkina Faso, Burundi, and Malawi, only 3% possess a title.Footnote 2 Within countries, titling rates vary across every level of administrative division. What explains the uneven uptake of formal property rights?

The confluence of local politics and national land regimes constrains household decisions to acquire a formal land title.Footnote 3 In addition to administrative fees, mapping complex patterns of land use onto individual titles creates risk for households. Consequently, households formalize their landholdings only when the value of the land, or the potential returns to agricultural investments enabled by titles, increases to the point that the benefits justify the costs. In countries with centralized land tenure regimes, titling erodes the authority of intermediaries who then impede formalization when they can. In countries which devolve responsibilities for land tenure administration to local governments, customary elites facilitate land titling because they can capture the process and maintain their authority.Footnote 4

I illustrate this theory using 170,216 household observations from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and Living Standards Measurement Surveys (LSMS) across 22 African countries. I introduce a geospatial measure of land values and the returns to agricultural investments which sidesteps measurement problems associated with informal and illegible property markets. These cross-national data document granular variation in the uptake of formal property rights and build a descriptive understanding of land tenure formalization across sub-Saharan Africa. These data also provide substantively and statistically significant evidence that the interaction between the strength of local customary institutions and national land regimes moderates this relationship. In centralized land regimes, strong customary authorities attenuate the relationship between land values and land tenure formalization: a 1,000 USD increase in the returns to long-term agricultural investment is associated with a 32% increase in the likelihood of possessing a land title where chiefs are strongest and a 66% increase where chiefs are weakest. In contrast, strong customary authorities in devolved land regimes strengthen the relationship between returns to agricultural investment and land tenure formalization. In such countries, the same increase in the returns to investment is associated with a 57% increase where chiefs are strongest, and no increase where they are weakest.Footnote 5

I use an in-depth case study of Côte d’Ivoire to unpack the mechanisms by which chiefs capture land titles and to show how chiefs use titling to advance their own political agendas. The history of migration in Côte d’Ivoire interacts with village land institutions to create local variation in the strength of customary elites. I leverage this natural experiment through an original field survey of 801 household heads and 194 customary elites across the Ivorian cocoa belt.Footnote 6 I show evidence for a number of intermediate observable outcomes of my theory: villages with stronger chiefs have more land titles, chiefs capture the land titling process, and chiefs leverage this capture to advance their political agenda by discriminating against relative outsiders (allochthones).

These results add to a voluminous literature in political science and political economy which seeks to explain the presence or absence of strong property rights. Much of this research centers how states and elites manipulate property rights for political or economic advantages: it asks why and when states and elites supply property rights (Albertus Reference Albertus2021; Boone Reference Boone2014; Nathan Reference Nathan2023). I nuance these theories by explicitly incorporating the household decision to seek a land title within my model and show that household demand for formal property rights varies significantly even within regions and districts. While much of the existing body of work treats property rights or institutions in abstract terms (Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001; Libecap Reference Libecap1989; North and Weingast Reference North and Weingast1989), I open the “black box” of property rights by showing how households interact with concrete and tangible land titles. This article also builds a descriptive understanding of the geographic variation in land tenure formalization across sub-Saharan Africa.

Informal institutions structure state-building efforts and economic development across the developing world (Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Cheema, Khwaja and Robinson2020; Díaz-Cayeros, Magaloni, and Ruiz-Euler Reference Díaz-Cayeros, Magaloni and Ruiz-Euler2014; Lust Reference Lust2022). They often facilitate economic growth by serving as development intermediaries (Balán et al. Reference Balán, Bergeron, Tourek and Weigel2022; Baldwin Reference Baldwin2016). However, informal institutions do not always “add value” to development; they can serve as either compliments or substitutes to the state (Baldwin, Kao, and Lust Reference Baldwin, Kao and Lust2025; Henn Reference Henn2023; Honig Reference Honig2022). Through the lens of property rights, this article enumerates conditions under which informal elites support or impede state-building and advances the study of how informal institutions shape both local and national politics.

The article proceeds in six parts. The first section establishes an empirical puzzle: few African households title their land despite the benefits to so doing and the availability of titles. The second section delves into a demand-driven theory of land tenure formalization to explain this discrepancy. The third section outlines the data sources I marshal to test this theory, as well as the paper’s methodology. The fourth section presents the quantitative results of these tests and documents how the interaction between strong customary institutions and land regimes moderates the uptake of land titling. The fifth section traces the intermediate steps of this theory by showing how powerful chiefs in Côte d’Ivoire capture the land tenure formalization process in a devolved land regime. The sixth section concludes the article.

FORMAL AND INFORMAL LAND TENURE IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

The majority of land in sub-Saharan Africa is held via informal, or customary, land tenure regimes. Across the most recent waves of the DHS and LSMS data collection, only 15.2% of landholding households possess a title for at least one of their agricultural parcels. The remainder hold their land through customary or informal rights, which are not registered and are rarely written. Customary land rights may be recognized by the state on a case-by-case basis, but are usually managed by customary authorities such as village chiefs.Footnote 7 In contrast, formal land rights are registered with state institutions, generally in the form of a written land title. Titles document a claim to the land (ownership, use rights, alienability, etc.) and carry legal weight.

Secure property rights incentivize investment because they increase the likelihood that one receives the returns to one’s investments (North and Weingast Reference North and Weingast1989). Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001) famously show that countries with better institutions—defined as those with a smaller risk of property being expropriated—are richer than countries with worse institutions.Footnote 8 This mechanism also holds at the household level: abundant empirical research illustrates the linkages between land tenure security and agricultural investment. In Ghana, officers of local customary institutions feel more secure in leaving their plots fallow and have consequently higher level of soil fertility and agricultural profits compared to non office-holders (Goldstein and Udry Reference Goldstein and Udry2008). In a randomized control trial in Benin, even land demarcation sans additional titling procedures led households to shift cultivation to crops which required a longer-term investment (Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Houngbedji, Kondylis, O’Sullivan and Selod2018). Dillon and Voena (Reference Dillon and Voena2018) show that households in Zambian villages where widows are unable to inherit land invest less in land quality. In India, households in areas with historically stronger landlords and weaker property rights have lower agricultural investments and productivity, even after independence (Banerjee and Iyer Reference Banerjee and Iyer2005). In the United States, uncertain title of railroads’ land grants delayed the development and irrigation of frontier Montana and reduced land values by up to 21% (Alston and Smith Reference Alston and Smith2022).

The policies of African governments reflect the importance of land tenure security. Since the 2000s, 41 African countries have established piecemeal, or on-demand land titling procedures (Honig Reference Honig2022, 2). In contrast to top-down land formalization programs, demand-driven programs allow households to opt-in to land tenure formalization. Land titles are available, but households are not obligated to seek them.Footnote 9

International donors also focus on land tenure security. The Land Portal Foundation, a consortium of international donor organizations, tracks 3,871 land governance projects around the world in its database. USAID alone has implemented land tenure projects in 23 separate countries. The World Bank and the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) also focus on land tenure issues.

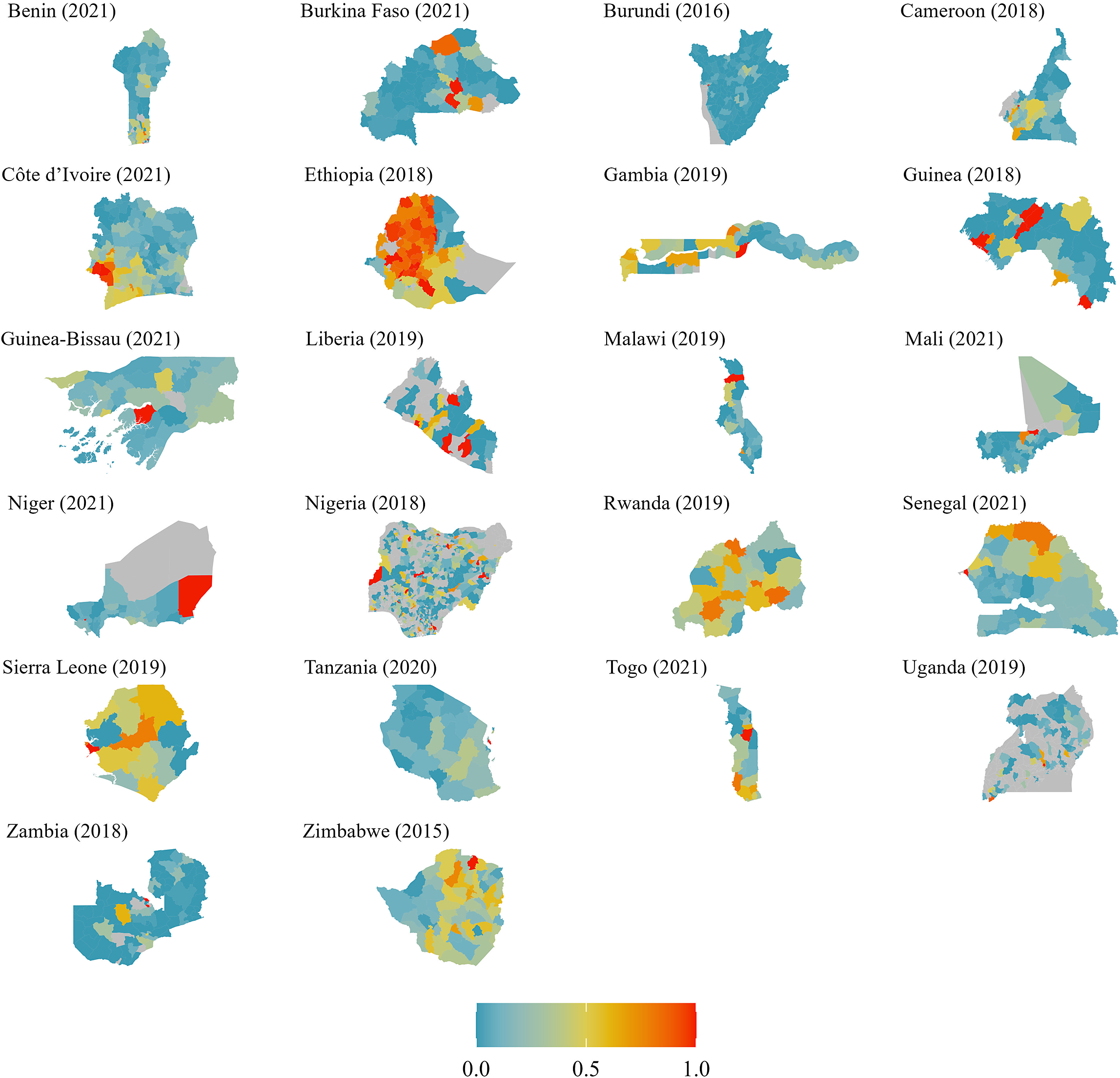

Titling remains rare across sub-Saharan Africa despite these efforts. Figure 1 documents extensive variation in the fraction of landholding households who possess a title, within both countries and regions. Areas with high rates of titling are not universally clustered around national capitals, or in resource producing areas. For example, there is a large concentration of formal land titles in the Fouta Djallon region of Guinea, a bastion of strong customary authority among the Peulh (Fulani) ethnicity. Mali’s highest rate of titling is in the fertile Mopti region, but several communes within the arid region around Gao also have high rates of titling. Even within the districts shown in Figure 1, the uptake of land tenure formalization varies dramatically across enumeration areas.

Figure 1. Subnational Variation in Land Titling Across 22 African Countries

Note: This figure shows the fraction of landholding households with at least one formal title for an agricultural parcel at the district (second-level administration division) level. Data are from the most recent round of the DHS and LSMS surveys. All calculations use provided survey weights. Table A13 in the Supplementary Material shows country-level averages.

These facts pose a puzzle. Rural households benefit from land titles. Many African states have made land titles available, often with support from international donors. Nevertheless, land titles remain rare, although high levels of spatial variation persist even within regions. What explains this limited uptake of land tenure formalization?

DEMAND-DRIVEN LAND TITLING

This section responds to the above puzzle by introducing a new theory of land tenure formalization in which household demand for land titles takes center stage. Households decide whether to formalize their land. Pursuing a land title is costly: households pay an administrative fee and incur risks when titling. Consequently, they only title when the benefits outweigh the costs. These benefits are increasing the value of land and the returns to potential agricultural investments. Chiefs have an incentive to impede titling, because titling displaces their role in customary land administration and removes a long-term reservoir of political authority. On the other hand, when land administration is devolved, chiefs can capture local land administration regardless of titling. In these contexts, chiefs facilitate land titling because they can manipulate titling to advance their political agendas without ceding control over land.

Household Balance Costs and Benefits

Land titling is costly. In Senegal, a land title costs around 5,000 CFA, or about 8 USD, per hectare. In Côte d’Ivoire, Bassett (Reference Bassett2020, 144) enumerates “over 20 steps to obtain a land certificate and another dozen to obtain a land title,” many of which involve a fee. These steps involve multiple levels of government: the village land management committees (CVGFRs), the sous-prefectures, and the Agence Foncier Rurale (AFOR) in the capital. Such processes are common across the continent.Footnote 10

However, the costs to titling go beyond monetary fees or time spent in the sous-prefect’s office. Land tenure formalization is not a one-to-one mapping of existing land use onto paper; it creates winners and losers. In much of Africa, agricultural parcels are subject to overlapping ownerships which exist in a state of strategic ambiguity (German Reference German2022; Lund Reference Lund2008). One person may have the right to farm in the dry season, another in the rainy season. A third person may have the right to graze their animals on the parcel. A fourth person may be the descendant of the original inhabitants of the area, who collects customary (but debatably ceremonial) rents. Which of these four owns the parcel? Land titling forces the issue of hierarchy between these partial owners. Formalization may carry a particular risk for “groups such as women, pastoralists, hunter-gatherers, casted people, former slaves, and serfs, who have traditionally enjoyed subsidiary or derived (usufruct) rights to land” (Platteau Reference Platteau1996, 40).

Households pursue titling despite the expense and the risk because land conflicts are an unfortunately common occurrence in much of Africa. In Côte d’Ivoire for example, settlement patterns by Burkinabé and Baoulé migrants led to large scale uprisings with as many as 4,000 casualties in the 1970s (Boone Reference Boone2003, 220). In parts of Northern Ghana, the dispossession of historical elites led to conflicts between the village chiefs and the dispossessed earthpriests (Lund Reference Lund2008). The fact that individuals who are more highly placed within customary institutions feel more secure in fallowing land likewise highlights the risk of expropriation (Goldstein and Udry Reference Goldstein and Udry2008). Formal property rights can help alleviate such concerns. Titling one’s land reduces the risk of losing it.Footnote 11

Households will be more willing to title their land when the value is higher. Where an asset is more expensive, households will go to greater lengths to protect it—including undertaking a costly titling process (Besley and Ghatak Reference Besley, Ghatak, Rodrik and Rosenzweig2010). These arguments echo political economy theories of endogenous institutions, which posit that property rights emerge when the individual benefits to organizing such a system become equal to the individual costs. Shifts in relative prices can shock prevailing equilibria and drive institutional change (Libecap Reference Libecap1989). Rosenthal (Reference Rosenthal1992, 21) illustrates this dynamic clearly in Revolution-era France, where “it was not worthwhile to define property rights to unimproved land clearly, for enforcing such rights would have required monitoring unwarranted by the low value of the land.” In the context of land formalization, a shift in the value of land should drive rural households to seek formal titles for their parcels.Footnote 12

Land titling also incentivizes households to invest in their land. Households with more secure land are able to invest with comparatively greater surety that they will receive the returns to these investments (Dillon and Voena Reference Dillon and Voena2018; Goldstein and Udry Reference Goldstein and Udry2008). These investment can be short term, such as fallowing one’s land or investing in fertilizer, or long term, such as planting tree crops which can take four to five years to become productive. The potential returns to investment in the parcel drive titling by incentivizing households to protect their future investments in the land.

Land tenure insecurity is not always the binding constraint to investing in one’s agricultural parcels. Much land in sub-Saharan is arid or infertile (Herbst Reference Herbst2014). Many seemingly lush tropical areas suffer from poor soil. In such areas, the benefits to households from seeking a formal land title will be lesser—more secure land title will not unlock investment where the potential returns to such investments are too low. These dynamics suggest that households will formalize their land only when the value of the land or the returns to investment in agricultural parcels is high enough to justify the costs. More specifically, I hypothesize that:

H.1 Households in areas where the value of land is higher will be more likely to possess a title.

H.2 Households in areas where the returns to agricultural investment are higher will be more likely to possess a title.

Chiefs and Precolonial Institutions

Households do not title in a vacuum. Most villages in sub-Saharan Africa have some manner of customary leader—most often a village chief (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2016). These chiefs have an incentive to prevent households from seeking land titles. However, chiefs do not always have the capacity to act on this incentive to prevent titling.

Customary authorities, most often chiefs, are important political actors across sub-Saharan Africa (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2016). Chiefs’ control over land reinforces their authority in other dimensions. Chiefs can use control over insecure land to sanction households who defy the chiefs (Acemoglu, Reed, and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson2014). Even without such threats, the role chiefs play in resolving land disputes enhances their perceived authority. Chiefs are often the first step to resolve land disputes (Ribar Reference Ribar2023). When households bring their disputes to the chief they implicitly recognize the chiefs’ authority to arbitrate such disputes. Lund (Reference Lund2008, 10) summarizes this point, that “[r]ecognition of property rights by an institution simultaneously constitutes a process of recognizing the legitimacy of the institution.” By keeping land rights in the customary regime, chiefs maintain a long-term reservoir of political legitimacy. Baldwin and Ricart-Huguet (Reference Baldwin and Ricart-Huguet2023) illustrate this dynamic: households across sub-Saharan Africa perceive their chiefs to be more authoritative where land values are higher because of increased competition over land. If control over land held in the customary system enhances chiefs’ political authority, then removing control of land to a centralized formal land regime will reduce their authority.

Chiefs also act as development intermediaries. Baldwin (Reference Baldwin2016) notes that much of chiefs’ legitimacy as political actors comes from their performance on the job: constituents prefer a chief that delivers development goods, such as roads or clinics.Footnote 13 Land titles are another form of development good. However, the extent to which chiefs can claim credit for such development goods depends on where decisions are made. Where land tenure administration is centralized, credit-claiming becomes more difficult, creating a second rationale for chiefs to impede titling.

Stronger chiefs are better able to act on their incentives to impede titling.Footnote 14 Scholars often measure the strength of precolonial institutions by the number of hierarchical layers of governance (Honig Reference Honig2022; Neupert-Wentz and Müller-Crepon Reference Neupert-Wentz and Müller-Crepon2024). Chiefs situated within hierarchical institutions are better able to prevent land titling because they are more empowered to enforce their decrees. Within weakly hierarchical institutions, customary elites may not have the political capital to enforce judgements (Boone Reference Boone2003). Increased within-village hierarchy may also help chiefs to hold households accountable because within-village elites such as lineage heads can convey grievances to or from the chief or act as the chief’s lieutenant.

A variety of literature explores how precolonial institutions affect contemporary outcomes. Honig (Reference Honig2022, 14), for example, notes that

Customary institutions with hierarchical legacies trace their roots to powerful precolonial states with hierarchical authority structures that withstood the colonial conquest… producing variation in the contemporary strength of customary institutions within each country.

Similarly, Wilfahrt (Reference Wilfahrt2022) notes how the overlap of precolonial institutions and contemporary state organs affects local redistributive politics in Senegal. Neupert-Wentz and Müller-Crepon (Reference Neupert-Wentz and Müller-Crepon2024) show that areas with hierarchical precolonial institutions have greater levels of contemporary political complexity. Precolonial hierarchy is especially pertinent when it comes to chiefly control over land, because much of the chief’s authority over village life is predicated upon their control over land (Acemoglu, Reed, and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson2014). Honig (Reference Honig2022) further argues that the presence of strong customary institutions reduces titling directly. Hierarchical institutions produce vertical accountability, in that customary elites can sanction other customary elites, as well as horizontal accountability, because these chiefs are subject to some degree of checks and balances. The result, Honig argues, is that these institutions “hold leaders accountable to institutional goals” and “slow the erosion of customary land tenure” (Reference Honig2022, 9).Footnote 15 This political authority means that chiefs are better able to act on their incentives to prevent land titling.

Putting these factors together, chiefs in centralized land regimes have an incentive to impede land titling, and stronger chiefs are better able to prevent titling. As a result, I hypothesize that

H.3 Strong customary institutions will attenuate the relationship between land values/returns to titling in countries where land tenure formalization is centralized.

Devolved and Centralized Land Regimes

Titling reduces the power of chiefs when it removes land administration to a centralized authority. However, titling can buttress, rather than diminish, the power of chiefs in areas where chiefs can capture the process. In countries with centralized land tenure regimes, decisions around land tenure formalization are made at the national level. For example, the Liberian Land Authority presents itself as a “one-stop shop” for land tenure formalization. Land administration and titling occur in Monrovia—far from customary institutions. Another strong example is Rwanda, where the country’s comprehensive land tenure formalization drive was managed entirely by the state. Rwanda selected areas in which to title, household claims were mapped, and then the central land registry office published the information (Ali, Deininger, and Goldstein Reference Ali, Deininger and Goldstein2014). Other countries devolve their land tenure regimes to local authorities. Land administration is a difficult task: agricultural land often exists in hinterlands where state capacity is comparatively limited (Herbst Reference Herbst2014).

Where control of land is devolved, chiefs are able to capture the land tenure formalization process. For example, municipal councils in Senegal issue the rural land certificates (délibérations foncières), but in practice the municipal councils rely on chiefs to guide land titling procedures and resolve disputes. In a survey of 1,164 household heads across rural Senegal, 92% of households said it would be necessary to inform the chief to acquire a délibération foncière, 47% said it would be necessary for the chief to investigate your claim, and 18% said it would be necessary to pay the chief (Ribar Reference Ribar2023). Similarly, village land management committees (comitès villageois de gestion foncière rurale, or CVGFRs) in Côte d’Ivoire investigate land claims, although titles (certificats fonciers [CFs]) are formally distributed by the national land bureau. Village chiefs have no official position in CVGFRs, but they nevertheless almost always head the committee.Footnote 16

Chiefs can capture devolved land titling in both neocustomary and statist land regimes (Boone Reference Boone2014, 24–5). In statist regimes, “governments administer the allocation and holding of rural property directly”; in the latter, land is governed indirectly through customary institutions.Footnote 17 Local land tenure arrangements are complex, heterogeneous, and often illegible to the state (Scott Reference Scott1998). As a result, chiefs play a large role in adjudicating land claims even when land administration is officially in the hands of the state. The important factor in my analysis is chiefs’ de facto control over titling, rather than their de jure control.

This capture of the titling process means that chiefs do not lose their power over land tenure, even when households seek title. As a result, chiefs can use titling to advance their own political agendas. For example, Onoma (Reference Onoma2010, 81) shows how chiefs in Ghana used land tenure formalization to “purchase and ensure political support.” Different chiefs have different incentives: in Côte d’Ivoire, chiefs’ primary agenda is to exclude outgroups from titling. Devolved land titling also opens space for chiefs to use land titles as development goods to increase their perceived legitimacy (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2016). Because land titling under devolved land regime lets chiefs advance their agendas without eroding their power, chiefs within a devolved land regime have an incentive to facilitate titling.

Strong chiefs are better able to act on these incentives—they have greater control over villagers and so can facilitate titling. Acemoglu, Reed, and Robinson (Reference Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson2014, 323), for instance, find that stronger chiefs in Sierra Leone “have more authority to influence whether or not people can farm or sell a piece of land.” It may also be the case that stronger chiefs are more able to capture land titling institutions, but my Ivorian case study suggests that even comparatively weak chiefs are able to control their village land committees.

This argument also does not contract Honig (Reference Honig2022), who argues that strong customary institutions prevent individual chiefs from acting against the collective interests of customary institutions. If titling does not go against the interests of customary institutions writ large—in this case, because chiefs can capture titling and maintain a degree of power over land—then the accountability provided by hierarchical institutions need not impede titling.

Why do some African states devolve land tenure? Centralized land tenure administration was the default condition across colonial Africa. Centralized administration was necessary to alienate productive land from African populations (Hailey Reference Hailey1938, 1649). Starting in the late 1980s, the World Bank promoted a number of decentralization proposals across the developing world (Deininger Reference Deininger2003). A number of MCC compacts, such as those in Benin and Niger, also promoted decentralization reforms. These reforms are largely donor-driven, rather than reflective of domestic politics. Decentralization programs are also a bad candidate for clientelist or targeted policies, because by nature, they affect entire countries. German (Reference German2022) further notes that many of the structural reforms and other projects are more reflective of a World Bank-driven “knowledge-regime” than of local circumstance.

In summary, customary land enhances the power of chiefs. When households title land, it exits the customary system. Where the administration of land tenure is devolved, chiefs can retain some control over land tenure through their capture of local land institutions, and so titling land does not erode the chiefs’ authority. In devolved land regimes, chiefs have an incentive to facilitate land titling so they can use it to advance their political agendas and potentially claim credit for providing a development good. Where land tenure formalization is centralized, titling disconnects chiefs from their reservoir of political authority and so they have an incentive to oppose it. The incentive to impede or facilitate titling does not confer the ability: stronger chiefs—measured through the presence of hierarchical precolonial institutions—are better able to act on these incentives. In contrast to areas with centralized titling, I predict that:

H.4 Strong customary institutions will strengthen the relationship between land values/returns to titling in countries where land tenure formalization is devolved.

DATA SOURCES AND METHODOLOGY

This section overviews the sources of data and methodology I use in the cross-country portion of the article. For the outcome variable, I combine 62 waves of DHS and LSMS data across 22 African countries to extract 170,216 household-level observations of land titling.Footnote 18 Next, I combine geospatial measures of agricultural suitability with historical commodity pricing to measure both the value of agricultural land and the returns to agricultural investment. Third, I introduce my measure of chiefs’ capacity to act on their incentives to impede or facilitate titling, measured through the hierarchy of local precolonial institutions. Finally, I introduce my original coding of country land regimes.

Outcome Variable: Household Titling

The lack of accessible administrative data on land titling has hampered the ability of scholars to study the subject. To sidestep this problem, I combine data from the DHS and LSMS projects. The DHS project collects comparable data on developing countries around the world. In its module on agriculture and landholding, the DHS asks “do you have a title deed or other government recognized document for any land you own?” Like the DHS, the World Bank’s LSMS program is a large scale effort to collect comparable data across the developing world. The LSMS contains a parcel-level roster of agricultural land and asks “[d]oes your household currently have a title or ownership document for this parcel.”

These similar questions allow me to construct the main outcome variable of the article: a binary indicator for whether a household possesses a title for at least one parcel of agricultural land.Footnote 19 I also extract the age, sex, and education of the household head, which I include as demographic control variables. Finally, I capture a binary indicator for whether the household has a title for their dwelling, which I use as a placebo outcome in Section A.3 of the Supplementary Material.

These data provide observations for 22 countries across 62 survey waves. Six countries have only one survey wave; the remainder have at least two. Survey data come from the period between 2010 and 2021, with only three waves taking place earlier (Uganda in 2005 and 2009 and Tanzania in 2008). While the DHS data have been collected since the late 1980s, questions about land tenure only appeared in round seven of DHS, which started in the mid-2010s.

Land Values and Returns to Investment

Illegible and informal land markets in most of Africa prevent researchers from directly measuring realized values of land.Footnote 20 To overcome these issues, I implement a novel measurement of “attainable value”: the value for which the maximum attainable yield (per hectare) could sell for on the international commodity market. I combine geospatial crop suitability data with global commodity prices to obtain these land values at a 10km-by-10km grid cell level. Adjusting the underlying parameters of the crop suitability models creates two measures of the returns to agricultural investment: the marginal increase in attainable value from using fertilizer, and the marginal increase in attainable value from planting tree crops as opposed to nontree crops.

I use version 4 of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)’s Global Agro Ecological Zone (GAEZ) model to obtain the “attainable yield” of different crop types. The model takes into account climate, soil and terrain data, as well as phenology and crop calendars to calculate the attainable yield of crops for a 10km by 10km grid.Footnote 21 Potential total production is divided by total grid cell area. Prices come from the IMF’s Primary Commodity Price System.Footnote 22 I set prices to constant 2011 USD. The commodities included in these data are: bananas, barley, chickpeas, canola oil, cocoa, coconuts, coffee, cotton, corn, groundnuts, oats, palm oil, rice, rubber, sunflower oil, soybeans, sorghum, sugar, tea, and wheat.

For each crop and grid cell, I multiply the maximum attainable yield (metric tons per hectare) by the commodity prices in a given year (USD per metric ton) to obtain the attainable price (USD per hectare) for each crop. I then take the maximum of this vector. More formally, the maximum attainable value

![]() $ \pi $

of grid cell g in year y is defined as

$ \pi $

of grid cell g in year y is defined as

where p indicates crop price, s indicates the attainable yield, and observations are indexed by g for grid cell, y for year, and c for crop. These data measure the maximum attainable value in constant 2011 dollars per hectare for a given 10km-by-10km grid cell on a yearly basis.

This measure calculates the attainable value of agricultural production per hectare; in other words, in captures the value of agricultural land. However, testing H2 also requires a measure of the returns to potential agricultural investment. To that end, I calculate two additional variables: the returns to using fertilizer (a short-term investment) and the returns to planting tree crops (a long-term investment). The primary land value measure assumes that households do not fertilize their parcels. Fertilizer is not a consistent or linear multiplier for yields. In some locations and for some crops, fertilizer greatly increases yields. Elsewhere, the returns are minimal. By re-calculating the GAEZ attainable yield models assuming fertilizer use, I can take the difference to identify the returns to fertilization.

I also calculate the returns to cultivating tree crops over nontree crops. Tree crops require a high up-front investment: households must purchase saplings or wait for trees to become productive. Coffee trees, for example, take five to seven years to become commercially viable. As a result, tree crops represent a longer-term investment than purchasing fertilizer for the remaining year. Of the 20 crops for which I have price data, I classify bananas, coconuts, cocoa, coffee, rubber, and tea as tree crops. I calculate the maximum attainable value for tree crops, and subtract the maximum attainable value for other crops. Where this difference is negative, I reset it to zero, in recognition that farmers would not make an unprofitable decision.

Farmers do not receive the global commodity prices. However, the validity of this measurement requires only that the prices farmers receive are positively correlated with global commodity pricing. In Section B.2 of the Supplementary Material, I probe this requirement using a subset of data for which households’ planting decisions are available. Households respond to this measure of attainable value: a 1% increase in the average attainable value per hectare of a crop is associated with a 0.13–0.16 percentage point increase in the amount of land that farmers dedicate to that crop. Similarly, an increase of 1% in the fraction of an administrative area in which a crop is the most profitable is associated with a 0.076–0.08 percentage point increase in the fraction of land that farmers dedicate to that crop. In other words, the elasticity of crop planting with regards to the crop’s attainable value is positive, which supports this land value measure capturing the underlying phenomenon of agricultural production.

This metric superficially resembles a shift-share instrumental variables (SSIV) design. However, my measure is not an instrument—attainable yield operationalizes the latent land values directly. The “methodology” section discusses my methodological precautions in greater detail.

The Strength of Customary Institutions

To measure the extent to which chiefs are able to act on their incentives to impede or facilitate titling, I use geo-referenced data from Murdock’s Ethnographic Atlas (Moscona, Nunn, and Robinson Reference Moscona, Nunn and Robinson2020; Murdock Reference Murdock1967), a common reference for differences among precolonial institutions. The Murdock dataset includes 89 variables on 802 different ethnic groups around the world, of which 239 are located in sub-Saharan Africa. The specific variable from the Murdock dataset through which I operationalize chiefs’ capacity is the precolonial institution’s level of hierarchy, which Murdock measures in two numbers:

the first indicates the number of levels up to and including the local community and the second those transcending the local community. Thus 20 represents the theoretical minimum, e.g., independent nuclear or polygynous families and autonomous bands or villages, whereas 44 represents the theoretical maximum, e.g., nuclear families, extended families, clan-barrios, villages, parishes, districts, provinces, and a complex state (Murdock Reference Murdock1967, 160).

This article uses the first of these numbers: the number of administrative levels within villages.Footnote 23 This local hierarchy is more likely to reflect local norms, rather than constellations of power which were sedimented by colonial regimes (Chanock Reference Chanock1991). Acephalous societies, such as the independent villages of northern Ghana, would rank at the lowest level (Nathan Reference Nathan2023). In Senegal the Imamate of Fouta Toto possessed a ruling council, regional chiefs, village chiefs, neighborhood chiefs, lineage heads, and household heads. Such a precolonial kingdom ranks at a four-four (the highest levels for both sets of hierarchy) on the Murdock scale.

Precolonial elites used the institutional discontinuity brought about by European rule to supplement their own authority (Berry Reference Berry2001; Boone Reference Boone2014; Lund Reference Lund2008). In many cases, what today constitutes “custom” reflects the powers that customary elites could convince the colonial state they possessed (Chanock Reference Chanock1991). In other cases, customary elites and chiefs were entirely invented by colonial powers (Nathan Reference Nathan2023). Nevertheless, what matters for my analysis is not the specific powers claimed by the village chief, but rather the extent to which the chief can act on their incentives to facilitate or impede land titling. Within-village precolonial hierarchy increases this ability because it provides the chiefs with more avenues to sanction households who act against the chief as well as subordinates—such as lineage heads—through which to administer the village.

There is undoubtedly noise in the relationship between precolonial hierarchy and contemporary institutions.Footnote 24 However, a variety of literature suggests that, on average, contemporary political institutions are stronger in areas where precolonial institutions were more hierarchical (Honig Reference Honig2022; Neupert-Wentz and Müller-Crepon Reference Neupert-Wentz and Müller-Crepon2024; Wilfahrt Reference Wilfahrt2022). This source of error should be uncorrelated with the independent or dependent variables, so this source of error would attenuate my results toward zero rather than bias them. As a result, one can consider this article’s results as a lower bound on the relationship between land values and titling.Footnote 25

Ultimately, the hierarchy of precolonial institutions is an indirect measure of the strength of contemporary customary institutions. However, it has a crucial advantage over alternatives: it is comprehensive. This measure covers the universe of precolonial polities in Africa. These data are geospatial, so they produce variation at the levels where my other data sources vary. Section D of the Supplementary Material provides additional evidence of the correlation between these Murdock data and the strength of current precolonial institutions.

Devolved and Centralized Land Regimes

Finally, I code whether land regimes in a given country are centralized or devolved. This distinction matters because chiefs are better able to capture the land tenure process where decision-making is devolved. I classify a land regime as devolved if decisions about whether a household can title a given parcel are made at the national level (centralized) or another level (devolved). This variable operationalizes the extent to which chiefs are able to capture land titling in a way that preserves my ability to make cross-national comparisons.

I specifically code this variable based on where the decision is made, rather than the location at which land titles are certified or recorded. For example, in Senegal, déliberations foncières are adjudicated, issued, and recorded by municipal councils, a third-level administrative devision. Côte d’Ivoire is a more complicated case: village-level CVGFRs decide who can obtain a certificat foncier, the sous-prefect verifies that correct procedures were followed, and the national land agency ultimately certifies the title. While administrative procedures take place at all three levels, this is a devolved land regime because villages make the decisions. The process is similar in Zambia: the Office of the Commissioner of Lands ratifies decisions made by chiefs (Honig Reference Honig2022). In contrast, the National Land Agency of Rwanda maps parcels, adjudicates titling, and issues certificates—a centralized land regime (Deininger and Goyal Reference Deininger and Goyal2024, 60–2). Section E of the Supplementary Material gives a complete list of countries and more detailed narratives which explains exactly how and why I classified these countries. No countries changed land regimes during the period of study.

Methodology

I analyze these variables using a series of linear probability models with fixed effects at the country-survey wave level. I also include a set of demographic controls, including the household head’s education level, sex, age, marital status, and whether the household is urban or rural. My geographic controls are measured at the second-level administrative division, and include geographic area, population density of the district, an interaction of area and population density, average terrain ruggedness (Carter, Shaver, and Wright Reference Carter, Shaver and Wright2019), caloric yield (Galor and Özak Reference Galor and Özak2016), average road density, and density of highways (Meijer et al. Reference Meijer, Huijbregts, Schotten and Schipper2018). I transform the road density variables using the inverse hyperbolic sine to improve normality.

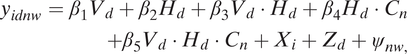

I model the moderating effects of land regime and informal institutions on the relationship between land values and titling through a series of triple interaction models. The triple interactions are necessary to capture the dependencies between land values/returns to investment, hierarchy, and land regimes. These regressions take the form:

$$ \begin{array}{r}{y}_{idnw}={\beta}_1{V}_d+{\beta}_2{H}_d+{\beta}_3{V}_d\cdot {H}_d+{\beta}_4{H}_d\cdot {C}_n\\ {}+{\beta}_5{V}_d\cdot {H}_d\cdot {C}_n+{X}_i+{Z}_d+{\psi}_{nw,}& & \end{array} $$

$$ \begin{array}{r}{y}_{idnw}={\beta}_1{V}_d+{\beta}_2{H}_d+{\beta}_3{V}_d\cdot {H}_d+{\beta}_4{H}_d\cdot {C}_n\\ {}+{\beta}_5{V}_d\cdot {H}_d\cdot {C}_n+{X}_i+{Z}_d+{\psi}_{nw,}& & \end{array} $$

where V indicates the land value variable (I estimate separate equations for each of three land value/agricultural investment variables), H represents the fraction of the district covered by hierarchical precolonial institutions, and C is a binary indicator for whether the country devolved its land administration. X and Z are vectors of household-level and district-level controls (respectively), i indexes observations by individual, d by district, n by country, and w by survey wave.Footnote 26 To facilitate interpretation, I also calculate marginal effects for all three land value variables. Tables 1–3 all include these control variables; Tables A1–A3 in the Supplementary Material replicate these analyses without controls, with similar results.

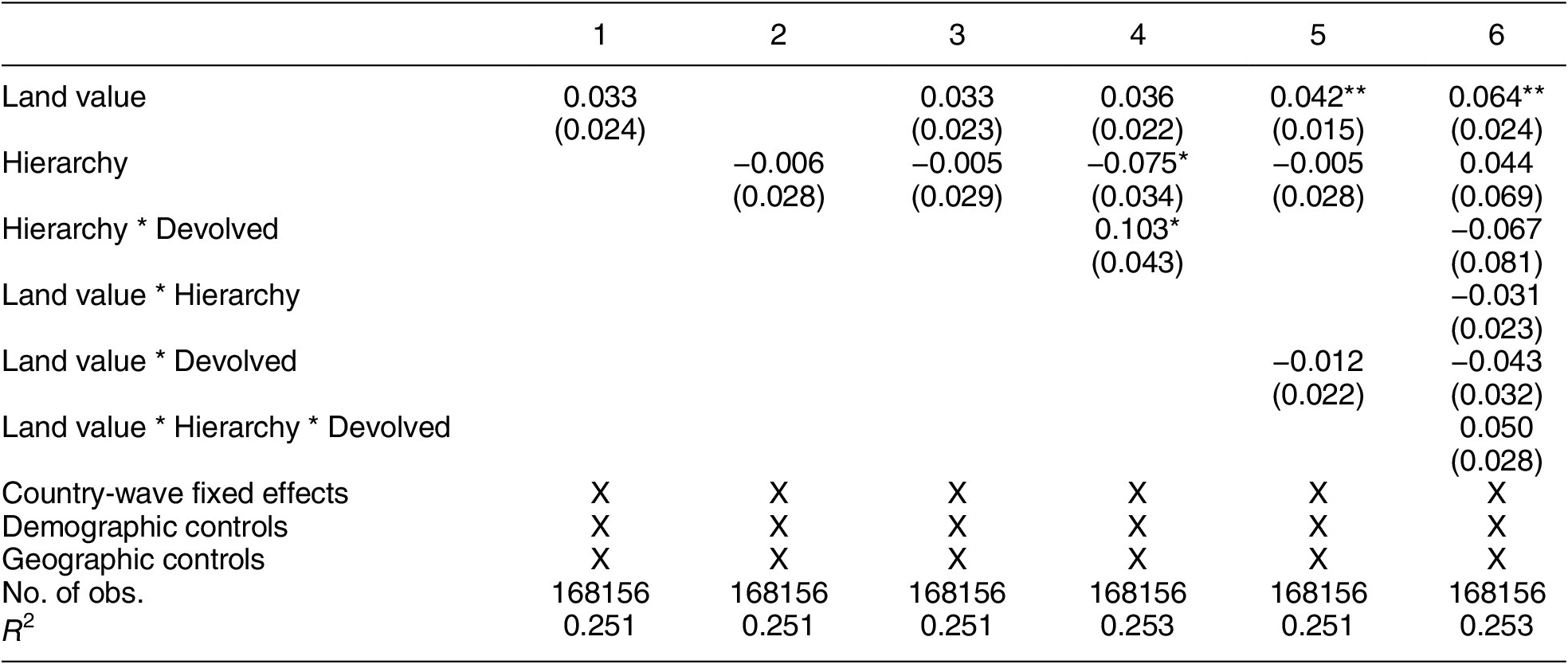

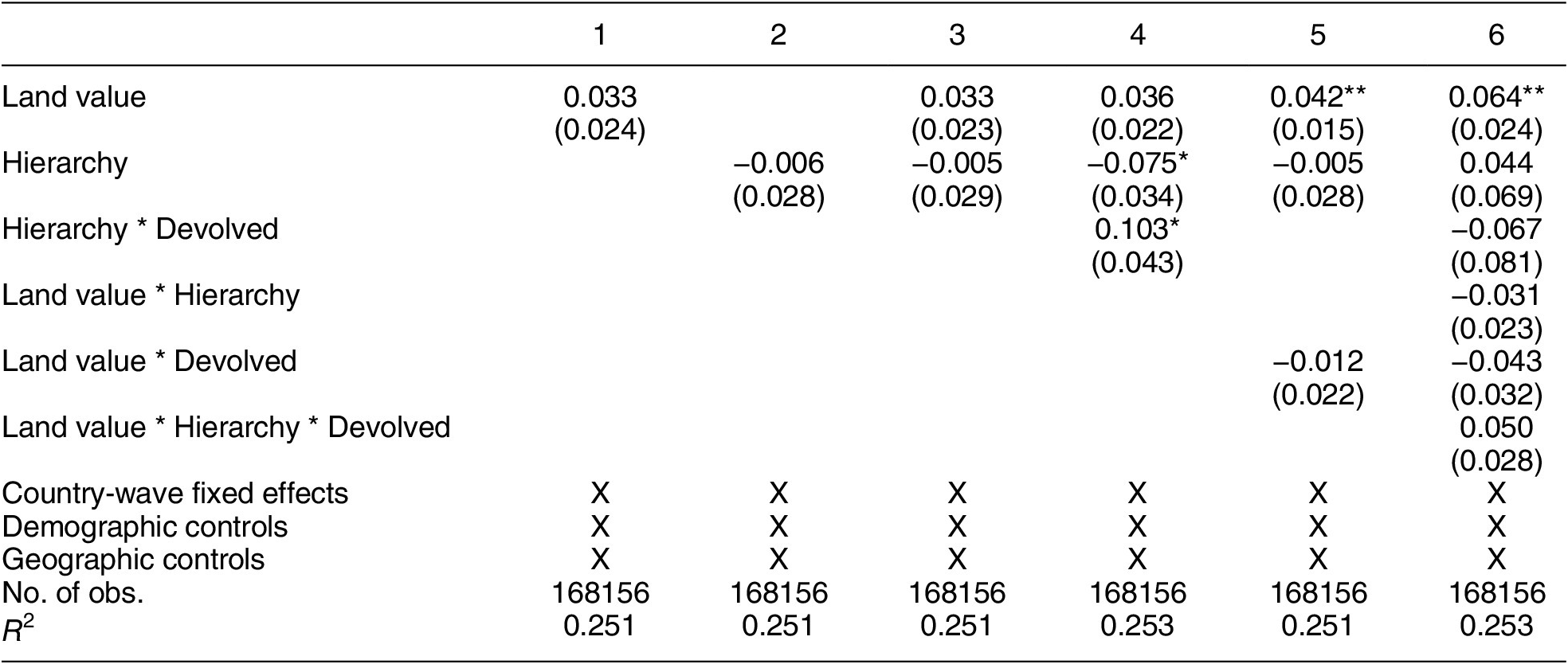

Table 1. Strong Customary Institutions Moderate the Relationship Between Land Value and the Uptake of Land Titles

Note: The dependent variable is whether a household possesses a land title. The independent variables are the maximum attainable value; the fraction of an administrative unit that is covered by a hierarchical precolonial institution; and whether the country devolved its land regime. The unit of analysis is the household. Land value data vary at the second-level administrative division. Demographic controls include the age, sex, and education of the household head; geographic controls include area, population density, an urban/rural indicator, road density, highway density, and terrain ruggedness. Table A4 in the Supplementary Material shows coefficients for these controls. Data are from the DHS and LSMS projects. All regressions use OLS with survey weights and country-wave fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the country-wave level.

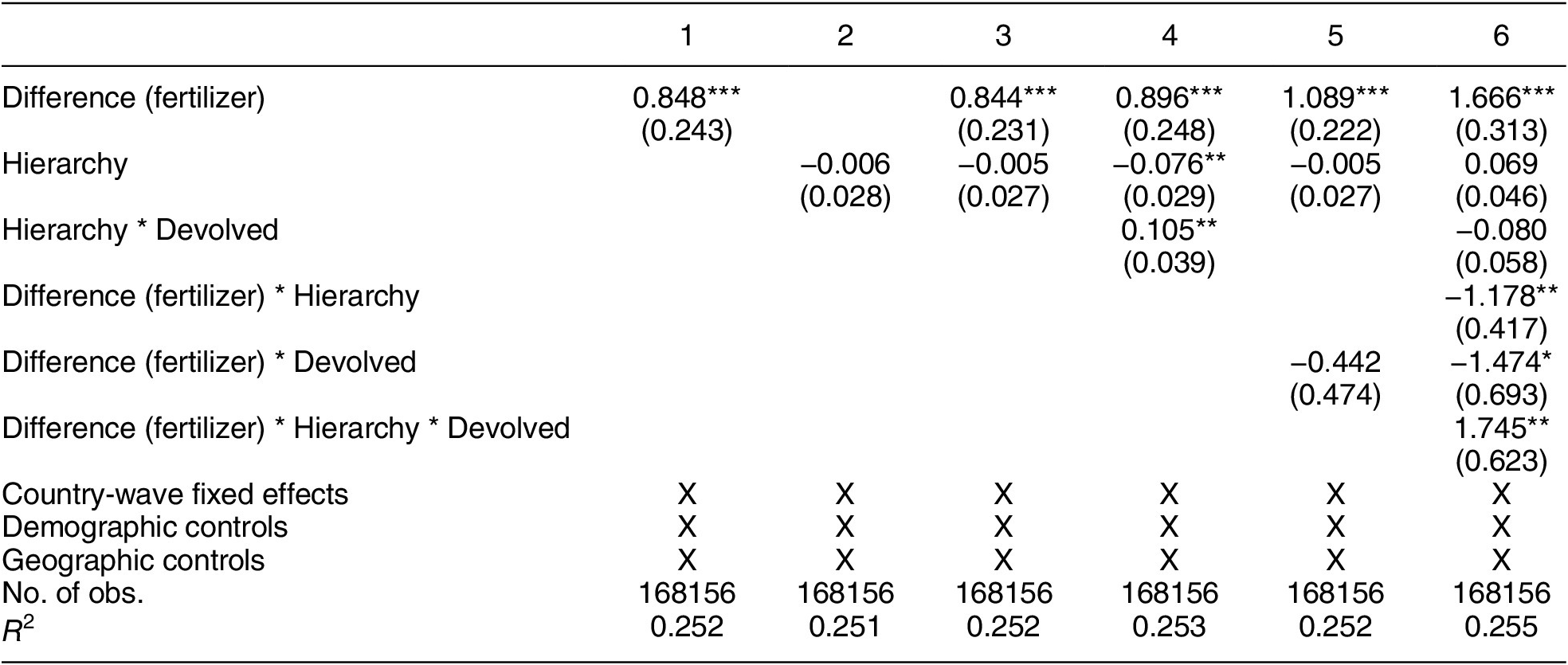

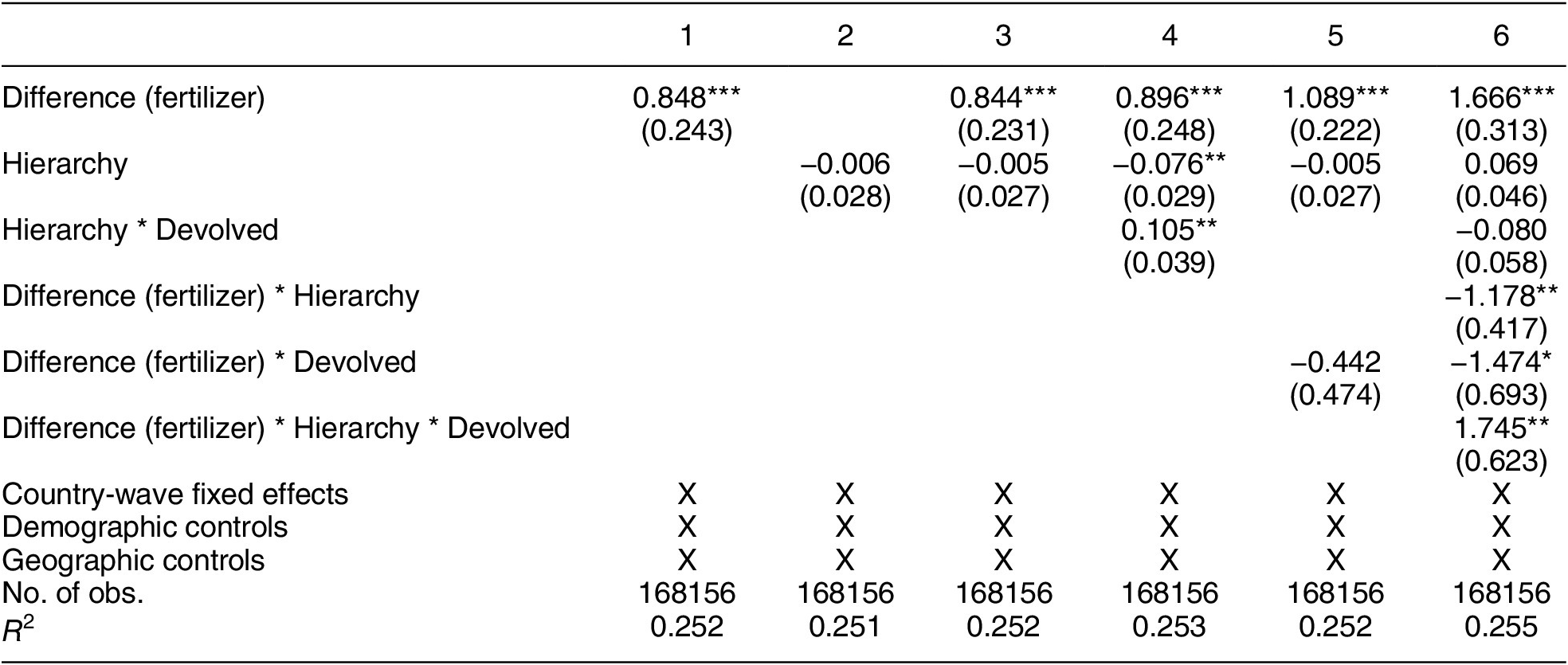

Table 2. Strong Customary Institutions Moderate the Relationship Between Returns to Fertilizer and the Uptake of Land Titles

Note: The dependent variable is whether a household possesses a land title. The independent variables are the increase in maximum attainable value from fertilizing a parcel; the fraction of an administrative unit that is covered by a hierarchical precolonial institution; and whether the country devolved its land regime. The unit of analysis is the household. Land value data vary at the second-level administrative division. Demographic controls include the age, sex, and education of the household head; geographic controls include area, population density, an urban/rural indicator, road density, highway density, and terrain ruggedness. Table A5 in the Supplementary Material shows coefficients for these controls. Data are from the DHS and LSMS projects. All regressions use OLS with survey weights and country-wave fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the country-wave level.

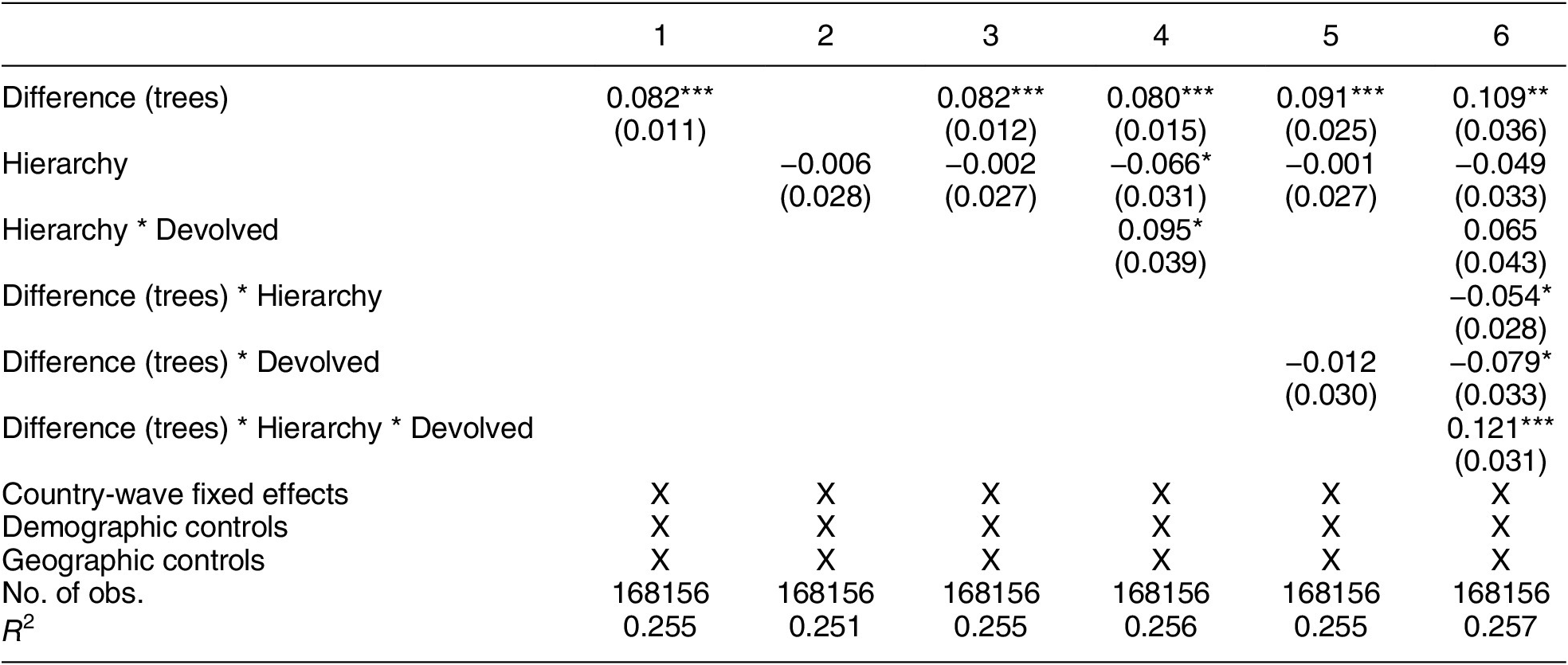

Table 3. Strong Customary Institutions Moderate the Relationship Between Returns to Planting Tree Crops and the Uptake of Land Titles

Note: The dependent variable is whether a household possesses a land title. The independent variables are the difference in maximum attainable value between planting tree crops and planting other crops; the fraction of an administrative unit that is covered by a hierarchical precolonial institution; and whether the country devolved its land regime. The unit of analysis is the household. Land value data vary at the second-level administrative division. Demographic controls include the age, sex, and education of the household head; geographic controls include area, population density, an urban/rural indicator, road density, highway density, and terrain ruggedness. Table A6 in the Supplementary Material shows coefficients for these controls. Data are from the DHS and LSMS projects. All regressions use OLS with survey weights and country-wave fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the country-wave level.

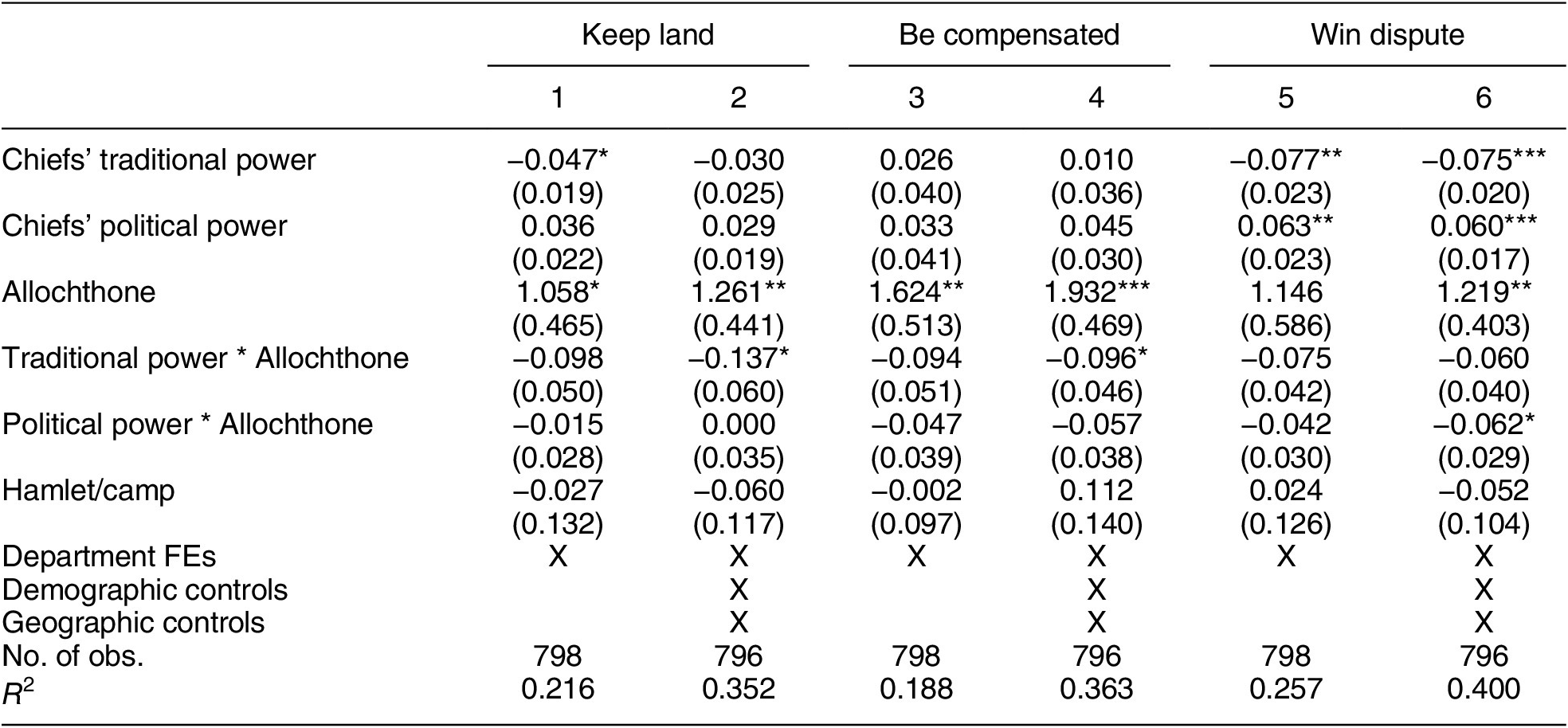

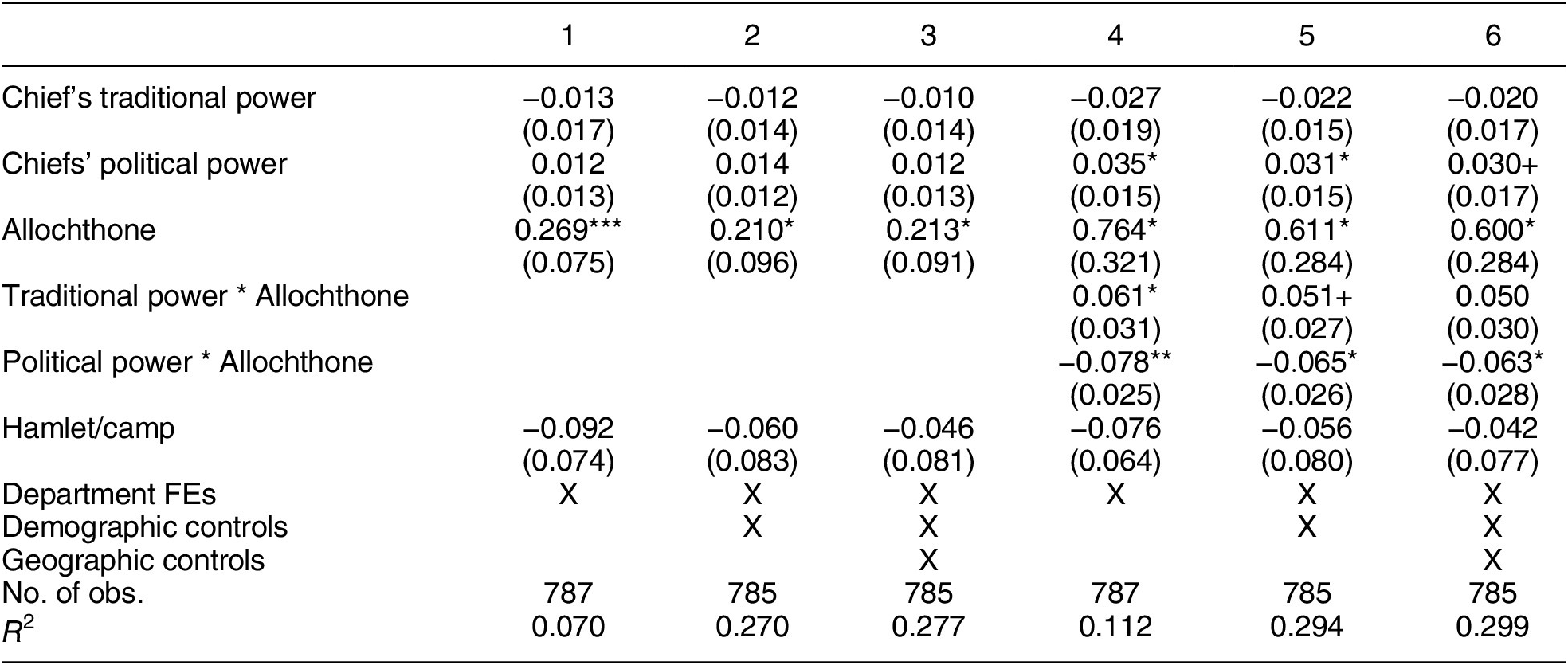

Table 4. Chiefly Authority Increases Titling for Autochthones but Not Allochthones

Note: The dependent variable is whether a respondent has a formal land title for at least one agricultural parcel. The independent variables are indices of responses to: [f]or each of these activities [that chiefs in Côte d’Ivoire sometimes mandate], I would like you to tell me how much of the village you think would do what the chief asked them to do. Demographic controls include education, sex, age, ethnicity, the respondent’s relationship to the household head, and wealth. Geographic controls include an indicator for PAMOFOR, distance to department capital, cocoa suitability, coffee suitability, and terrain ruggedness. Table C7 in the Supplementary Material shows coefficients for these controls. All regressions use OLS with inverse sampling probability weights. Standard errors are clustered at the administrative village level.

Threats to Inference

I measure land values by interacting the attainable yield per hectare for a variety of different agricultural products with their commodity prices on the global market and taking the maximum. This estimation strategy is a form of weighted exposure to common shocks design (Borusyak and Hull Reference Borusyak and Hull2020): the crop prices are the shocks, and the total attainable yields per hectare are the weights. These shocks themselves are exogenous; no individual farmer or country can affect the a crops global commodity price. One potential threat to inference in this case is that observations’ weights (i.e., their crop suitabilities) are likely not entirely exogenous to land titling. Soil quality may have other causal pathways to land titling rates; for example, Baldwin and Ricart-Huguet (Reference Baldwin and Ricart-Huguet2023) show that land quality affects the power of traditional leaders. In such cases, a nonrandom exposure to common shocks research design can lead to omitted variable bias (Borusyak and Hull Reference Borusyak and Hull2020). I include the average shock across all years for observation i to control for this bias.

A second threat to inference is that a country’s land tenure regime, centralized or decentralized, is endogenous to other variables. Albertus (Reference Albertus2021, 169), for example, points out that farmers who are “fixed geographically and lack property rights while facing obstacles to acquiring necessary agricultural inputs and credits are the stuff of clientelist party fantasy.” As a result, states may centralize land regimes in order to withhold titling. Many African leaders are also large-scale landowners, which gives them economic incentives to promote or withhold titling (Onoma Reference Onoma2010). Countries may also make the decision to devolve land titling on the basis of geography: devolution would be especially useful in countries with large hinterlands which complicate governance (Herbst Reference Herbst2014). Mali and Niger, for instance, both have sparsely populated hinterlands and devolved land tenure. However, small countries, such as Ghana and Lesotho, also devolved land tenure.Footnote 27 The decision to devolved tenure could also involve different social alliances and constellations of power: states are more likely to devolve power to rural elites who support their political regime (Boone Reference Boone2003).

Many of these variables—politics, geography, and political coalitions—may co-vary with land tenure regimes.Footnote 28 I control for the direct effect of these variables through country-wave fixed effects. I also control indirectly for both population density, administrative area size, and their interaction in all regressions which should control for being in a hinterland. Devolved land rights is also a national variable, whereas local power blocs or hinterlands are subnational. One important note is that these control variables do not eliminate the possibility that it is devolved land regimes which drive these results. Variables which correlate with devolved land tenure—such as state capacity or bureaucratic weakness—could confound these results when interacted with land values and strength of chiefs. Ultimately, the control variables and robustness checks minimize the probability of unobserved variables confounding my results, but do not eliminate it.

The concept of ownership is not constant across sub-Saharan Africa. Land ownership is often plural, in that multiple actors may have at least some claim over a particular parcel. Increased costs of titling due to plural ownership of land could reduce titling rates in certain areas and bias the results. The detailed subset of LSMS data collected as part of the EHCVM helps identify the extent of collective ownership. These surveys contain data on 148,885 separate parcels across 42,287 landholding households. Among these households, 70.6% individually own their parcels, 11% collectively own their parcels, and 18.4% own some parcels collectively and own some parcels individually.Footnote 29

Because my outcome variable is whether a household possesses at least one land title, so this statistical bias would exist only for the 11% who only hold land collectively. None of these 11% of households report owning their collectively held land; instead, they report holding it through loans or sharecropping agreements. I exclude these households because I limit my analysis to landholding households. While the DHS data collection does not ask the mechanism through which a household holds land, I have no reason to believe that collective ownership is more common in countries where DHS data collection took place than in countries where LSMS data collection took place. I cannot entirely exclude the possibility that differing norms of collective ownership create bias in my results, but statistics from a subset of the data suggest that this problem applies only to a small percentage of respondents.

Finally, another potential threat to inference comes from the potential endogeneity of donor funded land tenure formalization programs. Donors may target programs to areas where land values are high; in turn, these programs will likely increase rates of land titling. As such, donor funded land tenure formalization programs are a mediator variable, rather than a confounding variable (Morgan and Winship Reference Morgan and Winship2015). It is possible that adding this variable into my analysis would attenuate my results. Unfortunately, there is no comprehensive database of land tenure formalization programs with sufficient geographic granularity to explore this mediator. However, donor-funded land programs would only mediate the direct relationship between land value variables and titling. Land tenure formalization programs often subsidize the administrative costs of titling, but they do not change chief’s incentives to impede or facilitate land titling. As such, including donor-funded land programs would be unlikely to affect the overall marginal effects I display in Figure 2.

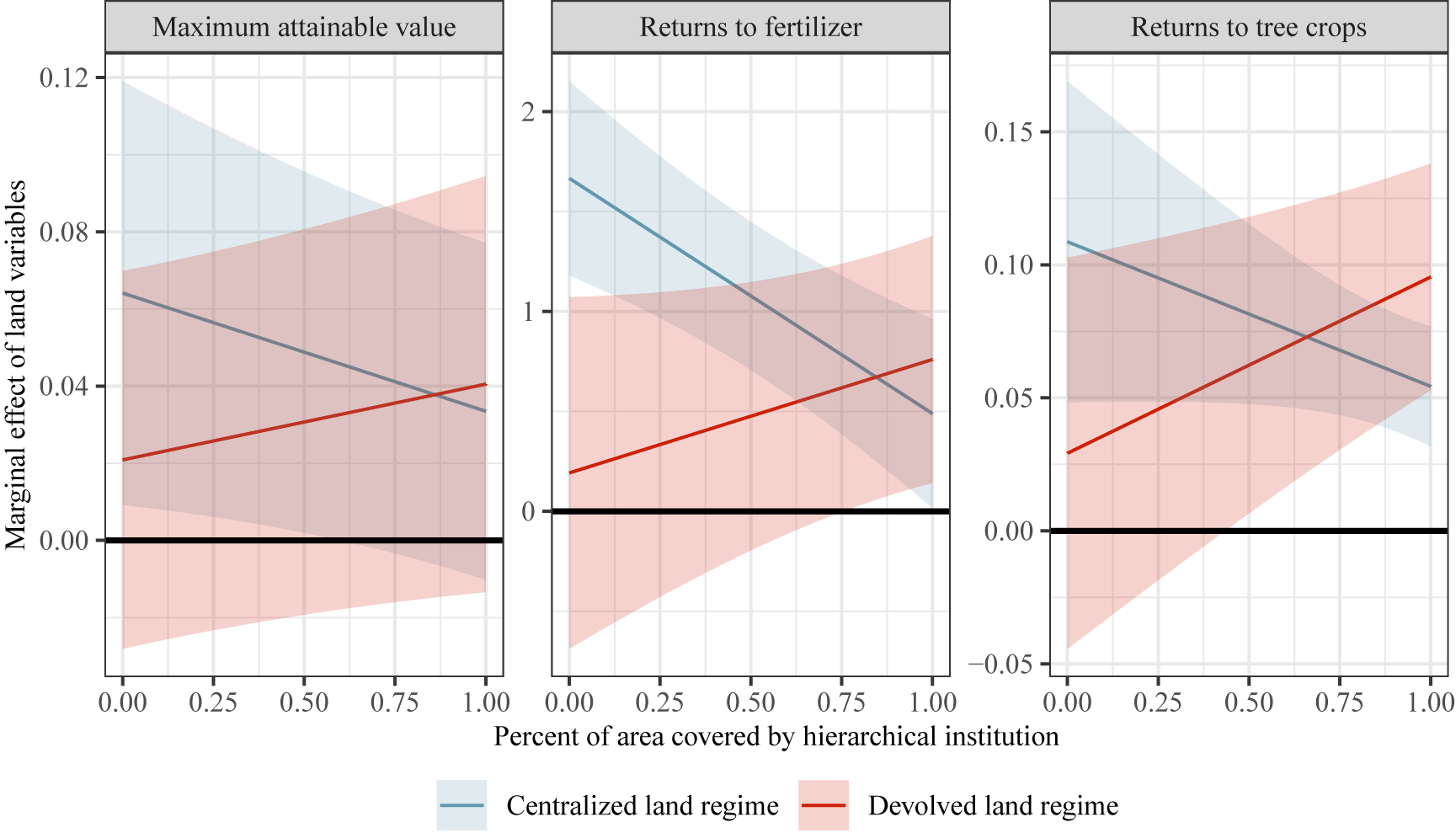

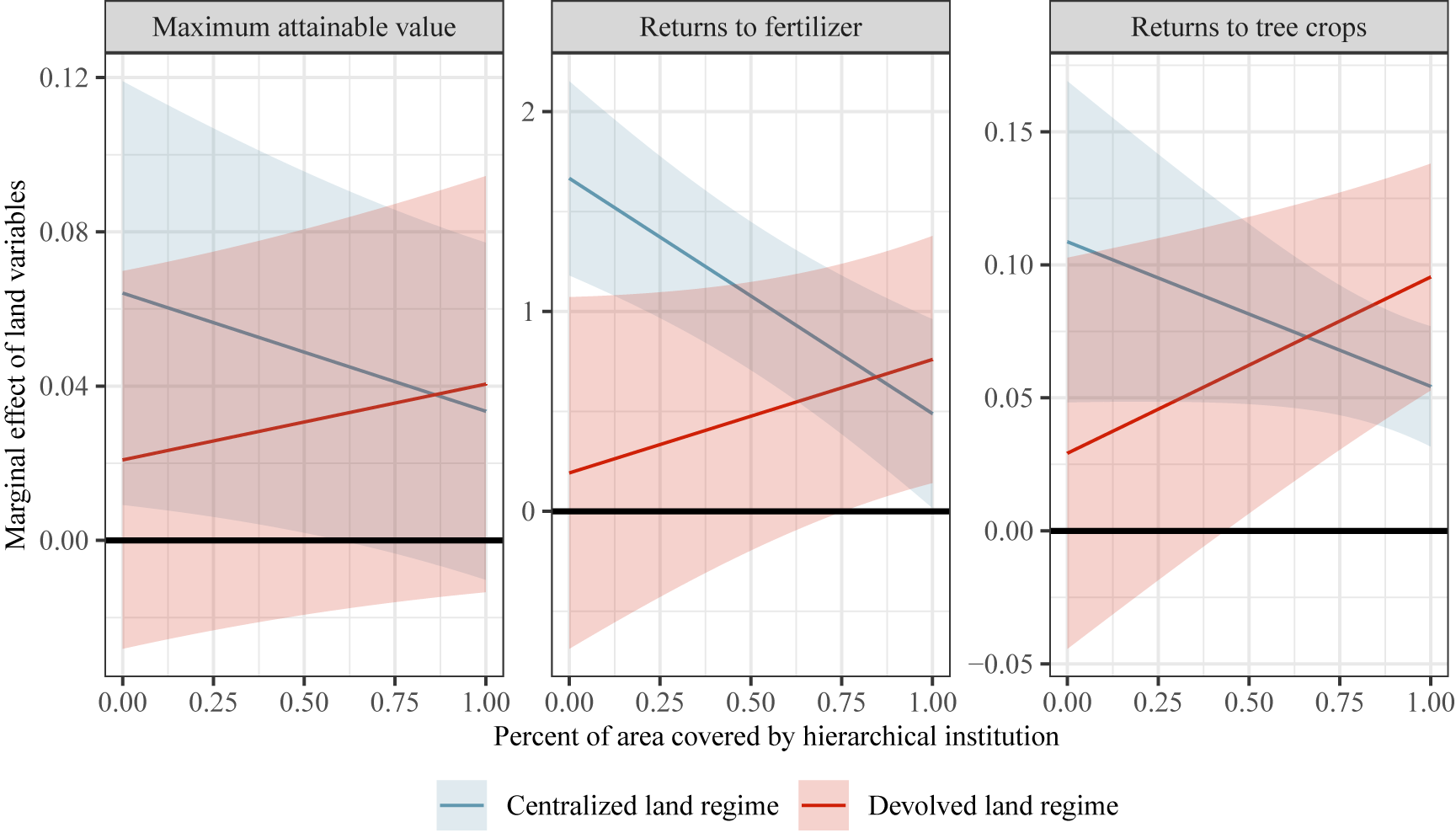

Figure 2. The Marginal Effect of Land Variables by the Presence of Precolonial Institutions Depends on the Prevailing Land Regime

Note: This figure shows the marginal effects of three land variables on the probability a household has a title, broken out by the percent of the administrative division covered by a hierarchical customary institution and whether the country has a devolved or centralized land regime. Results are from column 6 of Tables 1–3.

RESULTS

Previous theory suggests that both the value of land and the returns to agricultural investment should be positively associated with titling rates (H1 and H2). In countries with centralized land tenure regimes, strong customary institutions—measured by the hierarchy of precolonial institutions—will attenuate this relationship (H3). In countries with devolved land tenure regimes, strong customary institutions will strengthen it (H4).

Table 1 shows the results of regressing the household titling indicator on the maximum attainable value per hectare (in the previous year), in various combinations with the percent of the administrative division covered by a hierarchical precolonial institution and an indicator for whether the country has devolved its land regime. The maximum attainable yield per hectare has a qualitatively similar magnitude across specifications, though it only reaches conventional statistical significance in columns 5 and 6. In these specifications, a one standard deviation increase in the maximum attainable value per hectare (1.2) is associated with 0.045–0.053 percentage point increase in the likelihood of a household possessing a formal land title, which translated to a 27%–31% increase over the baseline probability of possessing a land title of 0.168. This table shows support for H1, but does not support H3 or H4: households title in response to higher land values, but the moderating effect of the interaction between land regime and strong customary institutions is unclear.

Table 2 repeats these analyses, but using the returns to fertilizing the parcel, which measures the potential for short-term investment in a parcel. The directionality of these results is identical, but they are consistently statistically significant. Across different specifications, a one standard deviation increase in the returns to using fertilizer (0.046) is associated with a 0.036–0.041 percentage point marginal increase to the likelihood of possessing a title, which translates to a 21.7%–22.6% increase over the mean titling rate of 0.168. These effects are both substantively and statistically significant—households who could make more money by using fertilizer are more likely to have a land title. Table 2 supports for hypotheses H2–H4.

Finally, Table 3 repeats these analyses using the returns to long-term investment in a parcel. This measure captures the marginal increase in maximum attainable value from planting tree crops rather than nontree crops (and is equal to zero if that difference is negative). These results are statistically significant and support H2–H4. Across models, a one standard deviation increase in the returns to planting tree crops is associated with a 0.039–0.041 percentage point increase in the likelihood of a household possessing a land title, an increase of 23.3%–24.6% over the baseline likelihood of possessing a land title (0.168).

To make sense of these triple interaction models, Figure 2 shows the marginal effect of the different measurement strategies for land value on titling rates by the strength of precolonial institutions, across both types of land regime. The vertical axes show the marginal effect of land value/returns to investment. In other words, the vertical axis shows the magnitude of the relationship between land values/returns to investment and land titling rates, conditional on other variables. For example, a value of 0.10 on the vertical axis for a given level of precolonial strength and a given land regime implies that within this subgroup, a one unit increase in the land value variable is associated with a 0.10 point increase in the probability of land titling. The horizontal axes show the percentage of the district covered by hierarchical precolonial institutions (the measure of a chiefs’ capacity to act on their incentives).

Figure 2 shows that across all specifications, the marginal effect of land values on land titling is weakly positive. The relationship between land values and land titling is never negative—only statistically indistinguishable from zero or positive. However, the magnitude of the relationship between land values and titling varies dramatically. Consistent with my theory, devolved land regimes invert the relationship between strong precolonial institutions and land values.

In countries with devolved land regimes, the relationship between land values and titling is weakly increasing in a district’s coverage by hierarchical precolonial institutions. Within devolved regimes, a one unit increase in the returns to tree crops is associated with a (statistically insignificant) 0.029 percentage point increase in titling rates at the lowest rates of hierarchy, and a statistically significant increase of 0.095 percentage points at the highest levels of hierarchy. The slope of the marginal effects is similar for the maximum attainable value and the returns to fertilization, but at no point do they cross the threshold for statistical significance. In summary, within devolved land regimes, the presence of hierarchical customary institutions strengthens the relationship between land values and land titles.

Centralized land regimes tell a different story. Within these countries, the relationship between land values and titling is positive and significant at all but the highest levels of precolonial hierarchy. A one unit increase in the marginal returns to planting tree crops within centralized land regimes is associated with a 0.111 point increase in the likelihood of having a title among households at the lowest levels of hierarchy. Among households at the highest level of hierarchy, a one unit increase in the returns to tree crops is associated with only a 0.053 increase in the likelihood of having a land title. The magnitude and significance of these results are similar for the maximum attainable value of a parcel and the marginal returns to fertilization. Strong precolonial institutions weaken the relationship between land values and titling within centralized land regimes.

These results paint a nuanced portrait of the relationship between the value of land, returns to agricultural investment, and the uptake of formal land titles. Consistent with H.1 and H.2, households with more valuable land—as well as those with higher returns to agricultural investment—are more likely to have a formal title for at least one of their parcels. However, local politics, in the form of strong customary institutions, interacts with a country’s land regime to moderate these relationships. In countries where land administration is centralized, households title less when chiefs are strong, consistent with H.3 and suggesting that chiefs impede titling. Households in countries where land regimes are devolved title more when their chief is strong, consistent with H.4.

One alternative mechanism that could explain these results is that households in areas with higher land values—or higher returns to agricultural investment—are simply wealthier. Higher levels of household wealth could alleviate monetary barriers to the uptake of titling, and therefore increase uptake. To test this mechanism, I conduct a series of placebo regressions using the same sets of explanatory variables, but with a binary indicator for whether the household has a formal title for their dwelling as the outcome. Titles for dwellings would be equally facilitated by increased wealth, but not by incentives to invest on agricultural land. These regressions (detailed in Table A7 in the Supplementary Material) show null effects across the board, suggesting that higher household wealth is not a mechanism through which land values drives titling. Population density also does not predict land titling rates, suggesting it does not capture the underlying value of the land (Table A9 in the Supplementary Material). Results are similar across British and non-British colonial powers (Table A8 in the Supplementary Material). Section A.4 of the Supplementary Material shows that these results are robust to a variety of model specifications, including excluding Ethiopia and Rwanda, log-transforming the geospatial variables, and subsetting to only the most recent survey wave.

CÔTE D’IVOIRE: CUSTOMARY ELITES IN ACTION

This section uses a case study in Côte d’Ivoire to show that chiefly authority increases land titling in a devolved regime, all else held constant, as well as to trace how chiefs use their capture of land titling to advance their political agenda. Côte d’Ivoire is a particularly useful case because its unique history of migration and land use has led to high variation in the authority of customary chiefs.Footnote 30 The country is a devolved land regime, where village land committees (CVGFRs) adjudicate titling decisions. Holding the land regime and land values constant means this case study isolates the relationship between chiefly authority and the uptake of formal property rights. This case study also illustrates that the positive relationship between strong chiefs and land titling in devolved countries does not simply attenuate the negative relationship in centralized regimes. Rather, strong chiefs in Côte d’Ivoire actively facilitate titling.

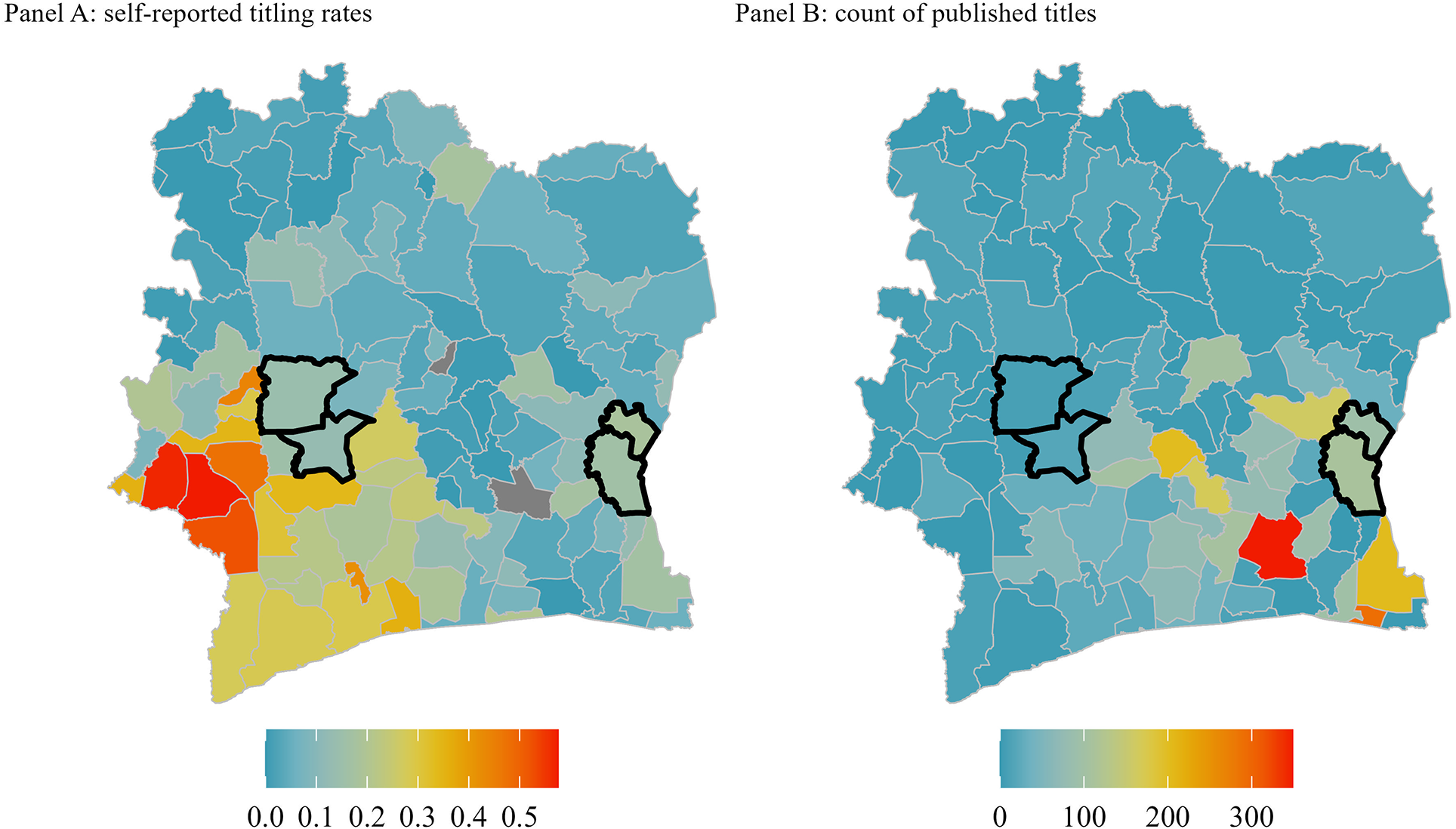

I unpack this case study through a field survey of 801 household heads and 194 customary elites in the Indénié-Djuablin and Haut-Sassandra regions.Footnote 31 Figure 3 highlights these areas, alongside two measures of household titling rates. Both regions cover the country’s central forest belt, where similar ecological conditions allow households to grow coffee, cocoa, rubber, and oil palms as cash crops.Footnote 32

Figure 3. Spatial Distribution of Land Titles Across Côte d’Ivoire

Note: The left panel shows self-reported titling rates by department from the 2021 LSMS survey. All averages use household weights. The right panel shows the count of CFs published in the Ivorian national gazette (Journal Officiel de la République de Côte d’Ivoire) as of November 7, 2022. The lengthy publication process makes these administrative data a lagging indicator. Highlighted administrative divisions show where the survey took place.

This case study also illustrates how chiefs use their control over land titling to further their political agenda. Land tenure in Côte d’Ivoire pits autochthones, or sons of the soil, against allochthones, or relative newcomers. Most areas have an autochthonous group, who are the descendants of the first inhabitants to “clear the bush.” Village chiefs are almost always autochthones. Later arrivals are called “allochthones,” or simply “strangers.” These relative newcomers often give symbolic gifts to acknowledge the precedence of the autochthones, though in many cases the allochthones have lived in the village for decades. Burkinabé families are particularly prominent among the allochthones, because the long-serving first president Félix Houphouët-Boigny recruited wealthy planters from Burkina Faso to increase Ivorian cocoa and coffee production (Zolberg Reference Zolberg1964). Autochthony is orthogonal to ethnicity; any ethnicity would be autochthonous in their homeland and allochthonous elsewhere. Arriving families often established their fields and households at some distance from the original village. Over time, these settlements grew into hamlets and campements. These hamlets often rival the original village in population and economic prominence; near Daloa, for example, allochthones now outnumber autochthones and hold most of the area’s land (Boone et al. Reference Boone, Bado, Dion and Irigo2021).

Village chiefs discriminate against allochthones when they can because chiefs perceive the allochthone’s land to be merely borrowed. The headman of an allochthonous hamlet near Abengourou to whom I spoke worried that the village chief would displace the hamlet in a few years when his cocoa trees became unproductive. An autochthonous farmer in the same region only permitted allochthones to farm land once he knew them personally, “to avoid them trying to claim the land.” AFOR, in contrast, is agnostic as to customary versus use-based claims to land. As a result, chiefly capture of the land tenure formalization process in Côte d’Ivoire manifests as discrimination against allochthones.

Strong Chiefs Lead to More Titles

Côte d’Ivoire devolved land tenure to CVGFRs, so my theory would predict that villages with authoritative chiefs would have more titles. I measure chiefly authority using seven survey questions: “[f]or each of these activities [that chiefs in Côte d’Ivoire sometimes mandate], I would like you to tell me how much of the village you think would do what the chief asked them to do.” The seven activities were: (1) Participate in village cleanup day; (2) Give up a piece of land for a school; (3) Spend a day repairing a road; (4) Spend a day planting trees; (5) Come to participate in a traditional dance; (6) Give money to support a traditional ceremony; and (7) Give up a piece of land for a mosque. For each activity, respondents answered: nobody, very few people, some people, most people, or everybody. I create two indices. One captures chiefs’ political authority and includes items one to four. The other captures chiefs’ authority in a more traditional sphere and includes items five to seven.Footnote 33 Chiefs’ political power is the metric which aligns with my overall theory: strong chiefs are those with higher political power. I include traditional authority for a comparison.

Overall, approximately 38% of households possess at least one formal land title. Table C6 in the Supplementary Material shows the relationship between the chiefly authority indices and household titling.Footnote

34 The outcome variable is a binary indicator for whether a household possesses a formal land title for at least one of their parcels. The independent variables are the two indices of chiefly authority. Columns 1–3 show no relationship between chiefly authority and titling. Columns 4–6, however, show that chiefs political power increases titling, but only for autochthones.Footnote

35 Among autochthones, a one standard deviation (

![]() $ \sigma =0.52 $

) increase in chiefs’ political authority is associated with a 0.13 percentage point increase in titling, an increase of 34% over the baseline rate. In contrast, a one standard deviation in political authority is associated with a 0.09 percentage point decrease in titling among allochthones, a decrease of 22% relative to the baseline rate of titling. These results paint a clear picture: in this devolved land regime, strong chiefs lead to more titles for the in-group (autochthones). However, in the Ivorian context, chiefly capture of land tenure administration means strong chiefs actually decrease titling rates among the outgroup (allochthones), in line with the chiefs’ agendas.Footnote

36

$ \sigma =0.52 $

) increase in chiefs’ political authority is associated with a 0.13 percentage point increase in titling, an increase of 34% over the baseline rate. In contrast, a one standard deviation in political authority is associated with a 0.09 percentage point decrease in titling among allochthones, a decrease of 22% relative to the baseline rate of titling. These results paint a clear picture: in this devolved land regime, strong chiefs lead to more titles for the in-group (autochthones). However, in the Ivorian context, chiefly capture of land tenure administration means strong chiefs actually decrease titling rates among the outgroup (allochthones), in line with the chiefs’ agendas.Footnote

36

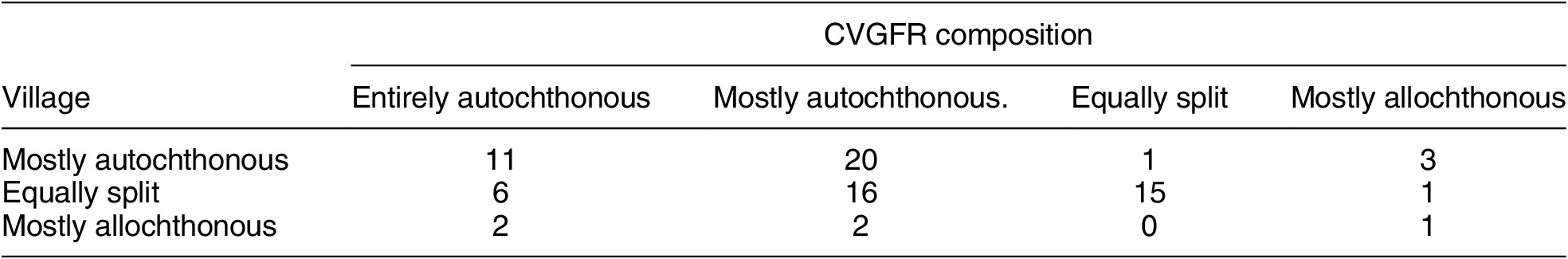

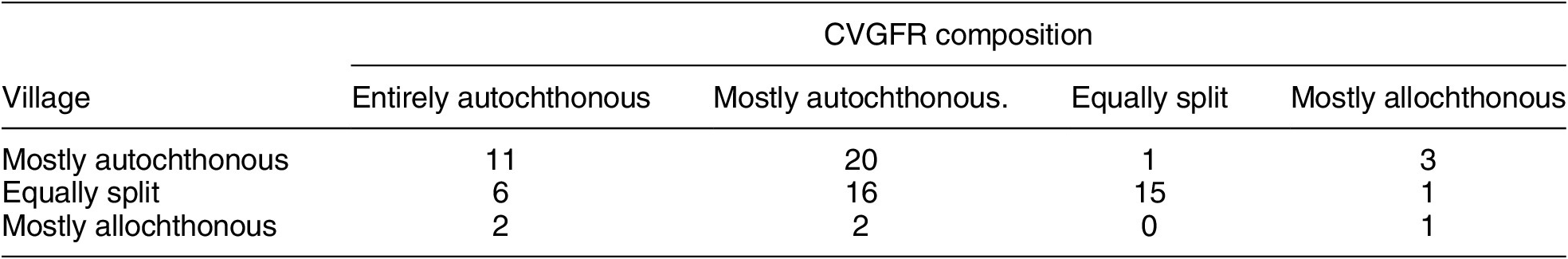

Chiefs Capture Land Management and Exclude Allochthones

How do chiefs capture titling? One mechanism is that chiefs dominate the CVGFRs and fill them with co-ethnics. CVGFRs investigate land claims and issue dossiers for potential CFs (Bassett Reference Bassett2020). The national land bureau (AFOR) ultimately records and issues CFs, but important decisions are made locally. I asked the chiefs of each village (1) whether the village was mostly autochthonous or allochthonous and (2) whether the CVGFR was mostly autochthones or allochthones. Table 5 shows that even in villages which are equally split or mostly allochthonous, autochthones dominate the CVGFRs.

Table 5. Chiefs Staff Village Land Management Committees with Autochthones

Note: Data from a 2024 survey of customary elites in the Haut-Sassandra and Indénié-Djuablin regions of Côte d’Ivoire.

Chiefs may also unevenly enforce land titles. If titles are less useful where chiefs are more powerful, it further suggests that chiefs can capture and control the titling process. In other words, strong chiefs may be able to overrule or override land titles. Table 6 shows whether respondents agree that: (1) having a title helps you keep your land if the government wants to take it; (2) having a title helps you be compensated if the government does take your land, and (3) having a title is useful in case of a dispute against your peers. If chiefs enforce titles unevenly, we would expect to see a negative coefficient on the interaction between allochthones and chiefly authority, because the chief’s agenda is to discriminate against allochthones.

Table 6. Autochthones More than Allochthones Think Strong Chiefs Make Titles More Useful

Note: Dependent variables are answers to “[d]o you think somebody with a certificat foncier would be (1-2) more likely to keep their land if the government attempted to take it; (3-4) to be compensated fairly for the land, were it taken” and (5-6) to succeed in a land dispute? All answers use a five-point Likert scale. Demographic controls include education, sex, age, ethnicity, the respondent’s relationship to the household head, and wealth. Geographic controls include an indicator for PAMOFOR, distance to department capital, cocoa suitability, coffee suitability, and terrain ruggedness. Table C8 in the Supplementary Material shows coefficients for these control variables. All regressions use OLS with inverse sampling probability weights. Standard errors are clustered at the administrative village level.

A clear divide emerges in Table 6 between the in-group (autochthones) and the out-groups (allochthones). Across all three categories, allochthones think titles are more useful. The chiefs’ authority has no relationship with the perception that titles are useful to be compensated for land expropriated by the government, which makes sense if households think such decisions are made at a higher political level. Across the remaining outcomes, a one standard deviation increase in chiefs’ traditional authority is associated with a 0.17–0.26 standard deviation decrease in the perceived utility of titles among autochthones. Among allochthones, the same increase in chief’s authority is associated with a larger 0.50–0.53 standard deviation decrease in the perceived usefulness of titles. All respondents think strong chiefs reduce the usefulness of titles, but this result is much stronger among allochthones, the out-group. Unlike previous results, it is chiefs’ customary authority, rather than their political authority that makes a difference. Land titles are less of a constraint on the behavior of more powerful chiefs which allows them to capture land management and discriminate against allochthones.

Chiefs are also able to extract rents from their control over titling. While chiefs have no official role in titling, 70% of the 801 respondents in my survey expected to have to pay chiefs to formalize a land title. Only 57% thought they would have to pay their CVGFR, which is actually empowered to title land and collect fees. More broadly, on average allochthones and autochthones thought they would have to pay 3.8 customary actors—actors without a de jure position in the titling process—in order to acquire a title.Footnote 37 These statistics show that chiefs’ role in titling process not only buttresses their political authority, but allows them to extract rents.

An alternative explanation for the broader results is that households title less when they have confidence that the chief can protect their property rights. Such trust would decrease the marginal increase of perceived land tenure security from titling one’s land, and therefore would reduce uptake of land titling. In Table C5 in the Supplementary Material, however, I show that trust in one’s chief does not increase either household titling or the extent to which households perceive land titles as valuable. This result accords with other recent literature, which suggests that the legibility provided by land titles is a valuable resource regardless of title’s legal weight (Ferree et al. Reference Ferree, Honig, Lust and Phillips2023).

By holding land values and the national land regime constant while varying chiefs’ power at a highly granular level, this case study sheds light into how customary authorities constrain the land titling process. Strong chiefs facilitate titling within their village—but only for the chiefs’ in-group. Moreover, allochthones perceive titles to be less effective, suggesting that enforcement of land titles may be unequal. While the cross-national analysis reveals broad trends which are consistent with the theory, this case study shows that the observable implications of this theory in Côte d’Ivoire align with the intermediate steps of the broader theory.

CONCLUSION

Secure property rights are a necessary condition for economic development. Land titles benefit households: titles reduce the risk of households losing their land and they make households feel more secure making profitable investments. These land titles are available on-demand in many African countries. So why do titling rates remain low across the continent?

Households whose land has higher attainable agricultural value and higher returns to agricultural investment are more likely to possess a title. However, the confluence of the strength of customary institutions and the country’s land regime moderate this relationship. Where land tenure administration is devolved, an increase of 1,000 USD in the returns to long-term agricultural investment is associated with a (statistically insignificant) 14% increase in titling rates where customary institutions are weakest, and a statistically significant increase of 55% where customary institutions are strongest. Where land tenure administration remains centralized at the national level, the same increase in the returns to long-term investment is associated with a 63% increase in the likelihood of having a title among households with the weakest customary institutions, and an increase of only 34% among households with the strongest customary institutions.