Non-technical Summary

This paper describes arthropod trackway fossils collected from the Wapiti Formation (Late Cretaceous) of west-central Alberta, Canada. The fossil trackways were found in mudstone that formed beside an ancient river system. In describing these fossilized arthropod trackways, we followed a new approach that should help other scientists characterize similar fossils. This way, our trackway can be easily compared with others and used in future studies of how such fossils should be classified. From the number and shape of the leg impressions, we identify the trackways as Octopodichnus cf. O. raymondi. Our trackways also show deep footprints and signs that the arthropod trackmakers used their multiple pairs of legs in different ways while walking (a pattern called heteropody). In addition to the arthropod trackways, the mudstone contains other invertebrate trace fossils (including burrows, fecal mounds, and surface trail/scratch marks) and abundant plant fossils. Volcanic ash situated directly above the mudstone may have helped preserve the trackway. Judging from the form of the tracks and the geological evidence pertaining to the environment in which they were made, the trackway was likely produced by a crayfish or a similar lobster-like animal that lived in a swampy setting. Most other Octopodichnus isp. trackways, by contrast, are thought to have been produced by scorpions and tarantulas in desert environments. This paper adds to the trace-fossil record of crayfish-like arthropods from the Late Cretaceous and helps document the little-studied invertebrate trace fossils of the Wapiti Formation and, more broadly, Cretaceous rocks in the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin.

Introduction

With the largest diversity in the animal kingdom today, and a rich fossil record dating back to the Cambrian explosion (e.g., Edgecombe and Legg, Reference Edgecombe, Legg, Minelli, Boxshall and Fusco2013), arthropods are arguably the most successful group of animals on Earth. However, their evolutionary history and paleobiogeography are not entirely clear. Aside from trilobites, ostracods, and some eumalacostracans, arthropods have weakly biomineralized external skeletons that are ill-suited for preservation in the rock record (Wills, Reference Wills2001). Trace fossils of arthropods not only provide records of their activity (such as locomotion, feeding, and burrowing) but also fill key gaps in their limited body-fossil record (Braddy, Reference Braddy2004; Dunlop et al., Reference Dunlop, Scholtz, Selden, Minelli, Boxshall and Fusco2013). One of the key characteristics of arthropods is their eponymous jointed appendages. Limbs and locomotor patterns vary among arthropods, resulting in a diversity of fossil trackways and trails (e.g., Walker, Reference Walker1985; Kluessendorf and Mikulic, Reference Kluessendorf and Mikulic1990; Minter et al., Reference Minter, Braddy and Davis2007). Recent neoichnological studies on arthropods have revealed how substrate conditions can affect the expression of trackways produced by different arthropods, allowing for interpretations of the trackmakers even when the producers are not preserved (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Minter and Braddy2007; Lima et al., Reference Lima, Minter and Netto2017; Devine and Minter, Reference Devine and Minter2022; Clendenon and Brand, Reference Clendenon and Brand2023). Historically, early palichnological studies of arthropod trackways often named these fossils on the basis of inconsistent criteria or overreliance on minor morphological variations, and without deep consideration of substrate effects, resulting in a confusion of ichnotaxonomic designations (Trewin, Reference Trewin1994; Minter et al., Reference Minter, Braddy and Davis2007). Thus, some arthropod ichnotaxa need reevaluation (e.g., Keighley and Pickerill, Reference Keighley and Pickerill1996; Minter and Braddy, Reference Minter and Braddy2009), and many trackways attributed to arthropods need to be redescribed using a more consistent approach (e.g., Trewin, Reference Trewin1994; Minter et al., Reference Minter, Braddy and Davis2007; Bertling et al., Reference Bertling, Buatois, Knaust, Laing and Mángano2022).

The Upper Cretaceous Wapiti Formation is a non-marine unit largely exposed in west-central Alberta and parts of east-central British Columbia, Canada. The formation is well known for its rich fossil record of vertebrates, especially non-avian dinosaurs (e.g., Currie et al., Reference Currie, Langston, Tanke, Currie, Langston and Tanke2008; Bell et al., Reference Bell, Fanti, Currie and Arbour2014; Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Currie and Burns2015; Holland et al., Reference Holland, Bell, Fanti, Hamilton, Larson, Sissons, Sullivan, Vavrek, Wang and Campione2021) but also fish, amphibians, non-dinosaurian reptiles, mammals, and birds (Fanti and Miyashita, Reference Fanti and Miyashita2009; Nydam et al., Reference Nydam, Caldwell and Fanti2010; Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Bell, Vavrek, Larson, Koppelhus, Sissons, Langone, Campione and Sullivan2022; Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Paparella, Bell, Campione, Fanti, Larson, Sissons, Vavrek, Balsai and Sullivan2023). The Wapiti Formation is currently divided into five informal lithostratigraphic units that correlate with other Campanian and Maastrichtian fossil-rich units of western North America on the basis of radiometric ages, sequence stratigraphy, and biostratigraphy (Fanti and Catuneanu, Reference Fanti and Catuneanu2009; Zubalich et al., Reference Zubalich, Capozzi, Fanti and Catuneanu2021; Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Bell, Vavrek, Larson, Koppelhus, Sissons, Langone, Campione and Sullivan2022).

The body-fossil record from the Wapiti Formation is supplemented by a rich record of vertebrate trace fossils, including tracks and trackways of non-avian dinosaurs (McCrea et al., Reference McCrea, Buckley, Plint, Currie, Haggart, Helm, Pemberton, Lockley and Lucas2014; Enriquez et al., Reference Enriquez, Campione, Brougham, Fanti, White, Sissons, Sullivan, Vavrek and Bell2020, Reference Enriquez, Campione, Sullivan, Vavrek, Sissons, White and Bell2021, Reference Enriquez, Campione, White, Fanti, Sissons, Sullivan, Vavrek and Bell2022), pterosaurs, lepidosaurs, mammals, and possibly amphibians (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Fanti and Sissons2013b; Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Bell and Sissons2013; Kimitsuki et al., Reference Kimitsuki, Rodriguez, Sullivan, Zonneveld, Sissons, Bell, Campione, Fanti and Gingras2024). Bite marks left on dinosaur bones have also been recognized (Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Currie and Burns2015; Holland et al., Reference Holland, Bell, Fanti, Hamilton, Larson, Sissons, Sullivan, Vavrek, Wang and Campione2021). By contrast, body and trace fossils attributable to invertebrates have received less attention, with Wapiti Formation occurrences limited to as-yet undescribed unionid bivalve casts, body impressions of larval mayfly specimens, and a sample of amber-trapped arthropods (Tanke, Reference Tanke2004; Bell et al., Reference Bell, Fanti, Acorn and Sissons2013a; Cockx et al., Reference Cockx, McKellar, Tappert, Vavrek and Muehlenbachs2020). Invertebrate trace fossils have been reported (“nematode and bivalve traces,” Bell et al., Reference Bell, Fanti, Acorn and Sissons2013a, p. 147; deposit-feeding and tubular locomotion traces, Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Bell and Sissons2013; Rhizocorallium, Enriquez et al., Reference Enriquez, Campione, White, Fanti, Sissons, Sullivan, Vavrek and Bell2022; Skolithos, Planolites, and Taenidium, Kimitsuki et al., Reference Kimitsuki, Rodriguez, Sullivan, Zonneveld, Sissons, Bell, Campione, Fanti and Gingras2024), but these occurrences await formal description.

Recently, mudstone slabs bearing well-preserved arthropod trackways, along with other invertebrate trace fossils, were collected from exposures of the Wapiti Formation on the Wapiti River near the city of Grande Prairie. In this paper, we describe these trackways in detail, assess them ichnotaxonomically, and consider possible trackmakers. Our study provides new insights into the invertebrate fauna of the Wapiti Formation and presents much-needed context for interpreting other Wapiti invertebrate trace fossils in the future.

Geological setting

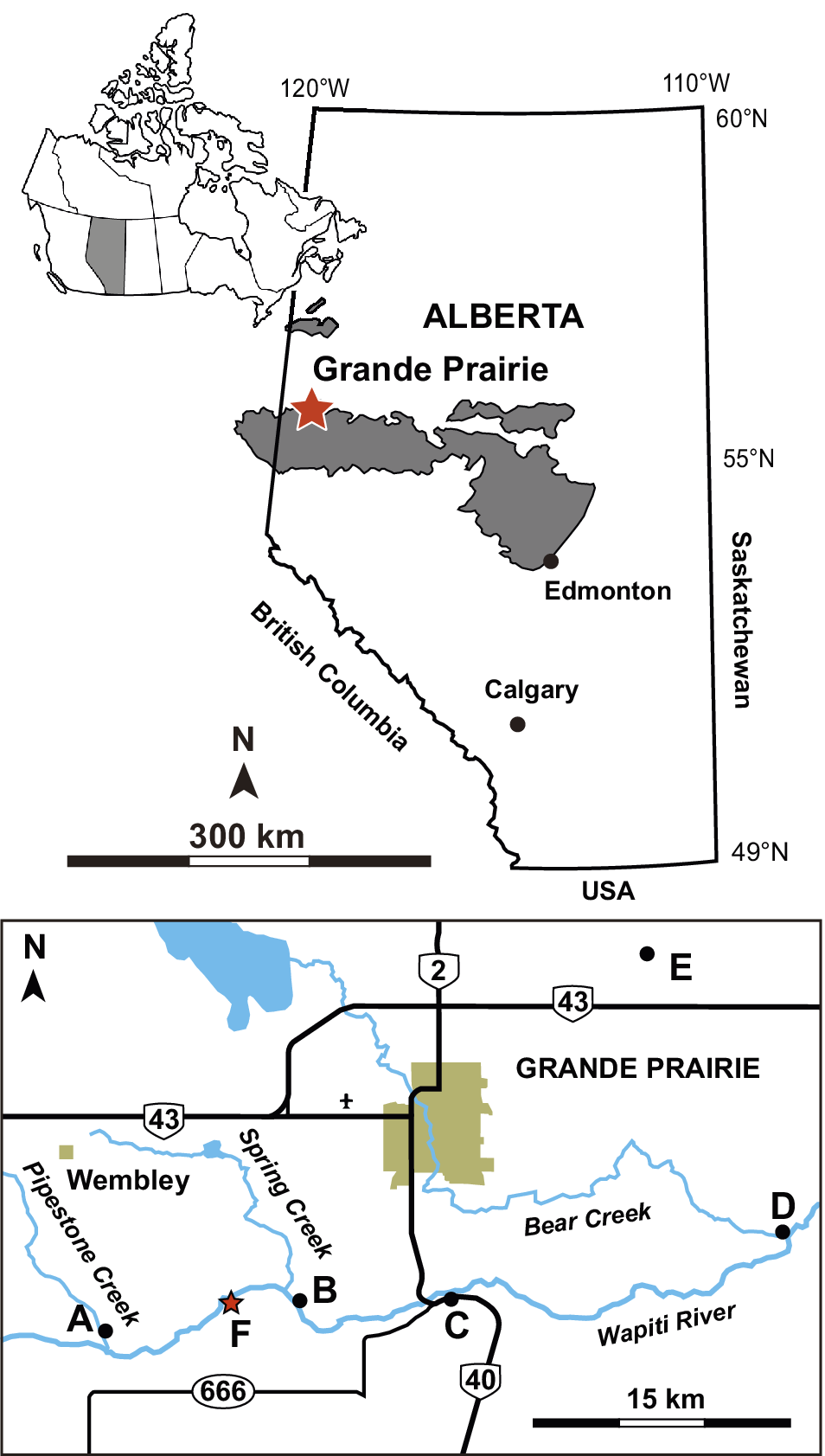

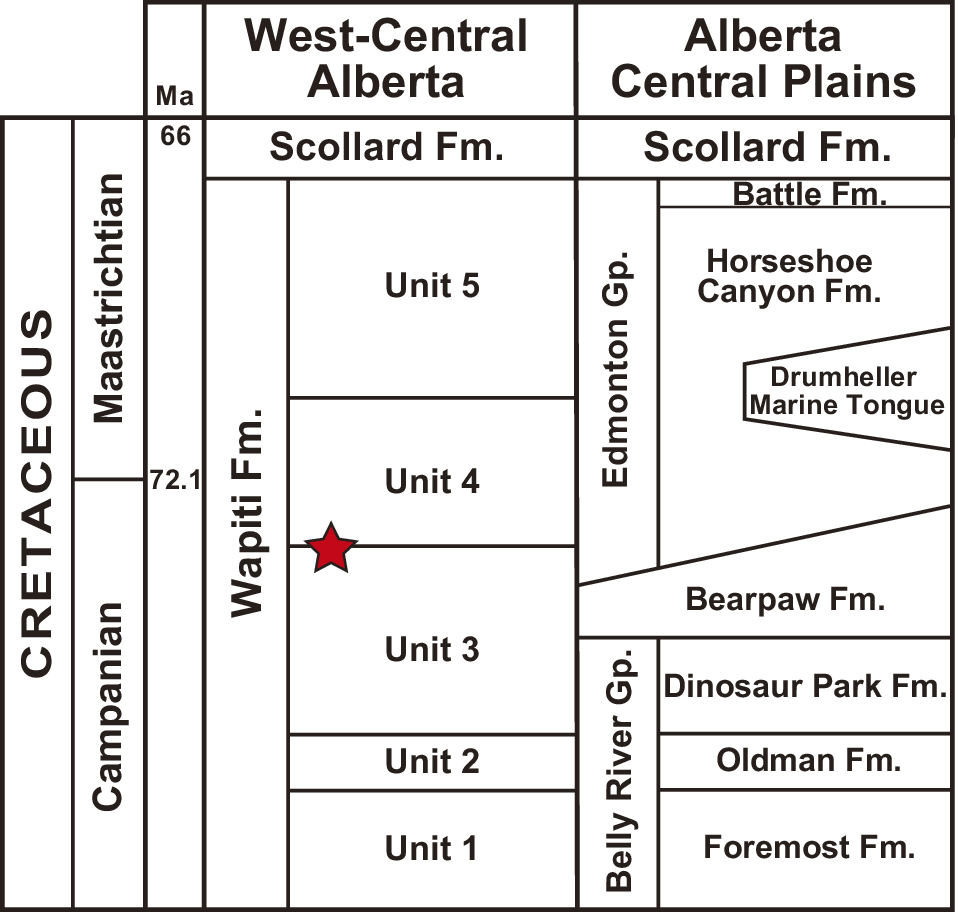

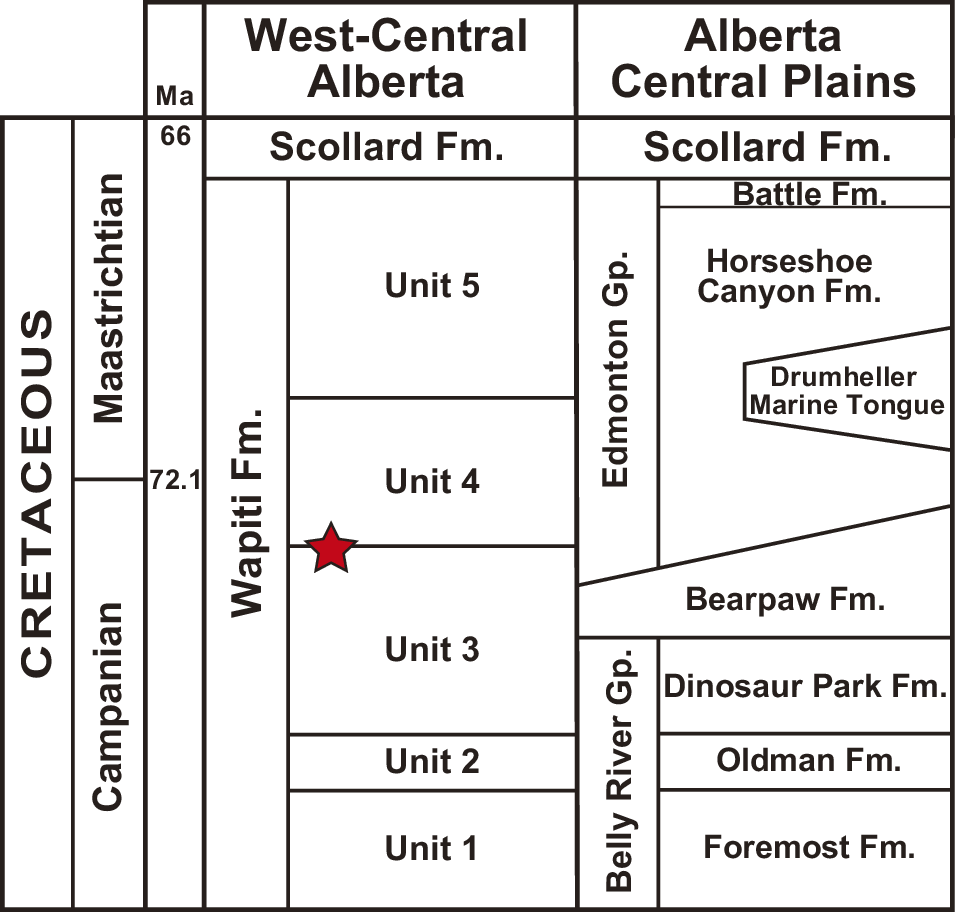

The mudstone slabs containing the fossil trackways were collected ex situ from exposures of the Wapiti Formation on the south bank of the Wapiti River, ~15 km southwest of Grande Prairie in west-central Alberta, Canada (55.070704°N, 118.992339°W). The locality is situated between the Spring Creek Bonebed—a monodominant assemblage of juvenile lambeosaurines (Holland et al., Reference Holland, Bell, Fanti, Hamilton, Larson, Sissons, Sullivan, Vavrek, Wang and Campione2021)—and the Pipestone Creek Bonebed, a monodominant assemblage of the ceratopsid Pachyrhinosaurus lakustai Currie et al., Reference Currie, Langston, Tanke, Currie, Langston and Tanke2008 (Fig. 1). Fanti and Catuneanu (Reference Fanti and Catuneanu2009) placed the Spring Creek Bonebed close to the top of Unit 3 of the Wapiti Formation (Fig. 2; see also Holland et al., Reference Holland, Bell, Fanti, Hamilton, Larson, Sissons, Sullivan, Vavrek, Wang and Campione2021), whereas the Pipestone Creek Bonebed is considered to lie within the lowermost part of Unit 4 (Cockx et al., Reference Cockx, McKellar, Tappert, Vavrek and Muehlenbachs2020; Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Bell, Vavrek, Larson, Koppelhus, Sissons, Langone, Campione and Sullivan2022). Given that the tracks described herein were found ~4 km upstream from the Spring Creek Bonebed, they are likely from the uppermost deposits of Unit 3 (Fig. 2). Overall, the upper portion of Unit 3 includes interbedded siltstone and sandstone, organic-rich mudstones, paleosols (either bentonitic or peat-rich), and coal seams deposited in and around high-sinuosity channels in a wet, lowland environment (Fanti and Catuneanu, Reference Fanti and Catuneanu2009). Integrated subsurface, outcrop, chronostratigraphic, and biostratigraphic data indicate that this unit is correlative with the upper Campanian marine Bearpaw Formation and the lower members of the transitional to non-marine Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Strathmore and Drumheller members) of central-southern Alberta (Eberth and Kamo, Reference Eberth and Kamo2020; Zubalich et al., Reference Zubalich, Capozzi, Fanti and Catuneanu2021). This period is characterized by the transgression of the Bearpaw Sea, and taxa recovered from Wapiti Unit 3 include terrestrial forms alongside others indicative of brackish and marginal-marine ecosystems that developed within tens of kilometers from the paleo-shoreline (Fanti and Miyashita, Reference Fanti and Miyashita2009; Koppelhus and Fanti, Reference Koppelhus and Fanti2019; Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Bell, Vavrek, Larson, Koppelhus, Sissons, Langone, Campione and Sullivan2022).

Figure 1. Map of the study area. The letters on the map indicate important fossil and geological localities. A: the Pipestone Creek Bonebed, a famous site overwhelmingly dominated by Pachyrhinosaurus lakustai Currie et al., Reference Currie, Langston, Tanke, Currie, Langston and Tanke2008; B: the Spring Creek Bonebed, containing a monodominant juvenile lambeosaurine hadrosaurid assemblage (Holland et al., Reference Holland, Bell, Fanti, Hamilton, Larson, Sissons, Sullivan, Vavrek, Wang and Campione2021); C: bentonite sampling site where Alberta Highway 40 crosses the Wapiti River; D: the mouth of Bear Creek, where two dated bentonite beds (Horizon B marker beds) are exposed; E: Kleskun Hill, a badlands exposure yielding diverse vertebrate fossils (Fanti and Miyashita, Reference Fanti and Miyashita2009); and F: the locality that yielded the arthropod trackways and other trace fossils described in this study, at 55.070704°N, 118.992339°W.

Figure 2. Stratigraphic columns for the study area in west-central Alberta and equivalent units in central Alberta. The probable stratigraphic position of the trace fossils described in this study, near the boundary between Units 3 and 4, is indicated by a red star. Modified from Kimitsuki et al. (Reference Kimitsuki, Rodriguez, Sullivan, Zonneveld, Sissons, Bell, Campione, Fanti and Gingras2024). Gp. = Group; Fm. = Formation.

The boundary between Unit 3 and Unit 4 has been defined primarily on the basis of well-log subsurface data and is marked by an unconformity between organic-rich mudstones of Unit 3 and coarse-grained channel and crevasse-splay deposits of lowermost Unit 4, recording an abrupt shift from high-accommodation to low-accommodation depositional conditions (Fanti and Catuneanu, Reference Fanti and Catuneanu2009, Reference Fanti and Catuneanu2010). From stratigraphic and paleocurrent analyses, Fanti and Catuneanu (Reference Fanti and Catuneanu2010) concluded that the unconformity also represents a shift from west–east oriented, high-sinuosity channel systems to southwest–northeast oriented, low-sinuosity channel systems.

Both the upper part of Unit 3 and the lower part of Unit 4 contain abundant volcanic ash beds related to continental-arc magmatism along the latitudinal extent of western North America (Fanti, Reference Fanti2009). A few of these ash beds have been dated (Fig. 1): Unit 4 bentonite beds from outcrop exposures along Highway 40 (~14 km east of the study area) were dated to 72.4 ± 0.7 Ma with U–Pb (Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Bell, Vavrek, Larson, Koppelhus, Sissons, Langone, Campione and Sullivan2022). Farther away, two bentonite beds at the mouth of Bear Creek (~33 km east of the study area) and one at Kleskun Hill (~35 km northeast) belong to Unit 3. The Bear Creek beds were dated to 75.26 ± 0.8 Ma and 73.5 ± 0.8 Ma with U–Pb (Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Bell, Vavrek, Larson, Koppelhus, Sissons, Langone, Campione and Sullivan2022), and the Kleskun Hill bed to 73.77 ± 1.46 Ma with Ar–Ar (Eberth in Fanti, Reference Fanti2007).

Sedimentology

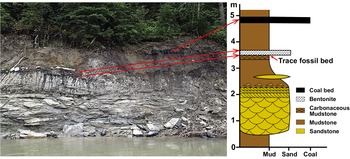

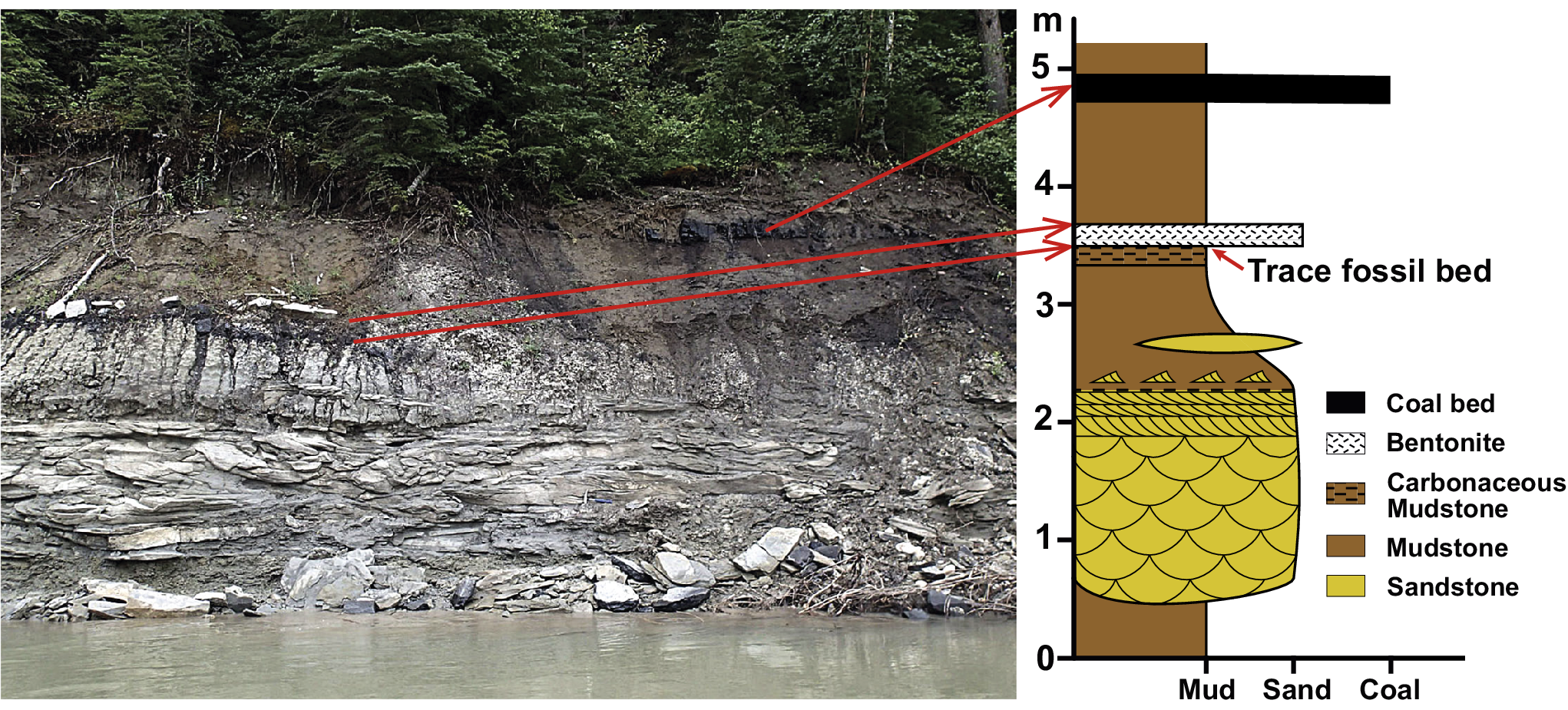

The base of the outcrop (~5 m high exposure) from which the track-bearing mudstones were collected is formed by an ~1.5 m thick, medium- to fine-grained sandstone bed with large-scale trough cross bedding, which overlies an unconformity and gradually fines upward into bioturbated mudstone deposits (Fig. 3). The mudstones that host the tracks are ~10 cm thick and occur approximately 1 m above the top of the cross-bedded sandstone. The track-bearing mudstone bed is characterized by high organic content, giving the rock a dark gray to black coloration that contrasts with the light gray of the underlying mudstone. This carbonaceous mudstone is directly overlain by a thin (~10 cm thick), massive, white to pale yellow bentonite. The mudstone overlying the bentonite is reddish brown and capped by a bed of coal. It is also worth noting that the locality is approximately 10 m upstream of Ursus Point Paleofloral site, where a mudstone bed underlying the cross-bedded sandstone contains well-preserved fossil leaves (data based on curated materials at the Philip J. Currie Museum).

Figure 3. Image of the outcrop that yielded the trace fossils described in this study, with accompanying stratigraphic section. The trace fossils were found on the upper surface of a carbonaceous mudstone that is overlain by bentonite.

The track-bearing mudstone bed is planar laminated with fragments of carbonized plant material and thin (~1 mm) coal layers oriented parallel to the bedding plane. Notably, plant remains also occur on the upper surface of the slab but are not carbonized, instead being silicified and white to light gray in color. The top surface also bears remnants of the overlying bentonite, which appear as white smears on the surface or infill the trace fossils. In addition to the trackways described herein, the bedding surface displays a diversity of other invertebrate trace fossils and organic matter. Despite the abundance of plant material, there is no evidence of root traces, and the mudstone has not been pedogenically altered.

The fining upward sequence, with cross-bedded sandstone overlain by sandy mudstone and coal, is interpreted to represent a fluvial depositional setting, consistent with previous studies’ interpretations of the Wapiti Formation in the study area (Fanti and Catuneanu, Reference Fanti and Catuneanu2009, Reference Fanti and Catuneanu2010; Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Bell, Vavrek, Larson, Koppelhus, Sissons, Langone, Campione and Sullivan2022). The large-scale trough cross bedding present at the bottom of the outcrop is consistent with migrating channels (Cant, Reference Cant, Scholle and Spearing1982; Donselaar and Overeem, Reference Donselaar and Overeem2008; Swan et al., Reference Swan, Hartley, Owen, Howell, Ghinassi, Colombera, Mountney and Reesink2018), whereas the overlying mud and coal deposits and the track-bearing mudstone suggest a more quiescent mode of deposition, consistent with a poorly drained alluvial floodplain (Roberts, Reference Roberts2007; Fanti and Catuneanu, Reference Fanti and Catuneanu2009; Swan et al., Reference Swan, Hartley, Owen, Howell, Ghinassi, Colombera, Mountney and Reesink2018). The limited amount of exposure makes interpretations regarding channel morphologies challenging; however, the well-developed fining upward sequence, thick mud and coal deposits, and high proportion of mudstone with respect to sandstone support deposition in a meandering river system (Cant, Reference Cant, Scholle and Spearing1982; Fanti and Catuneanu, Reference Fanti and Catuneanu2009, Reference Fanti and Catuneanu2010).

The dark color of the carbonaceous track-bearing mudstone indicates elevated organic matter content, which in turn suggests that the sediments were deposited in a swampy environment such as floodplain ponds, marshes, and/or oxbow lakes (cf. Wing, Reference Wing1984; Roberts, Reference Roberts2007). Immersion in a standing body of water can lead to enhanced preservation of plant material by preventing oxidation and biodegradation (Kraus and Davies-Vollum, Reference Kraus and Davies-Vollum2004). Although deposition in standing water could also explain the planar laminae of the mudstone, similar bedding can be produced through biogenic stratification (e.g., Dafoe et al., Reference Dafoe, Rygh, Yang, Gingras and Pemberton2011), which could be the dominant process in this case judging from the abundance of invertebrate burrows. The fact that the plant remains on the top surface of the track-bearing mudstone bed are silicified instead of carbonized is noteworthy. Silicification of plant material requires substantial input of silica and is often associated with hydrothermal activity or volcanic deposits (cf. Matysová et al., Reference Matysová, Rössler, Götze, Leichmann, Forbes, Taylor, Sakala and Grygar2010). In this case, the volcanic ash layer directly above the mudstone likely provided the silica.

Materials and methods

The site was originally discovered during a prospecting excursion along the Wapiti River as part of Boreal Alberta Dinosaur Project (BADP) fieldwork in the northern summer of 2023, during which one track-bearing mudstone slab was collected. The area was revisited in 2024, and two additional slabs were collected. All three slabs were found ex situ at the base of an exposure on the south bank of the Wapiti River (Fig. 3); however, the source layer is unequivocal owing to the unique lithology of the mudstone (discussed in the preceding).

Three-dimensional models of the trackway-bearing slabs were constructed to facilitate investigation of the morphology of the trace fossils. The high-resolution reconstructions of the slabs allowed topographical analysis of minor indentations. For each slab, the surface bearing the tracks was photographed using a digital camera, and photogrammetric models were constructed using Agisoft Metashape Professional Version 1.6.5 (Agisoft LLC, 2020). These models were then exported as orthomosaics, and the trace fossils were measured using the ruler tools in Adobe Photoshop Version 23.1.0 (Adobe Inc., 2021). Digital elevation models (DEMs) were also constructed using Metashape and were used to perform topographical analyses. Four trackway segments (which are numbered TW1–TW4) are measured and described.

Terminology

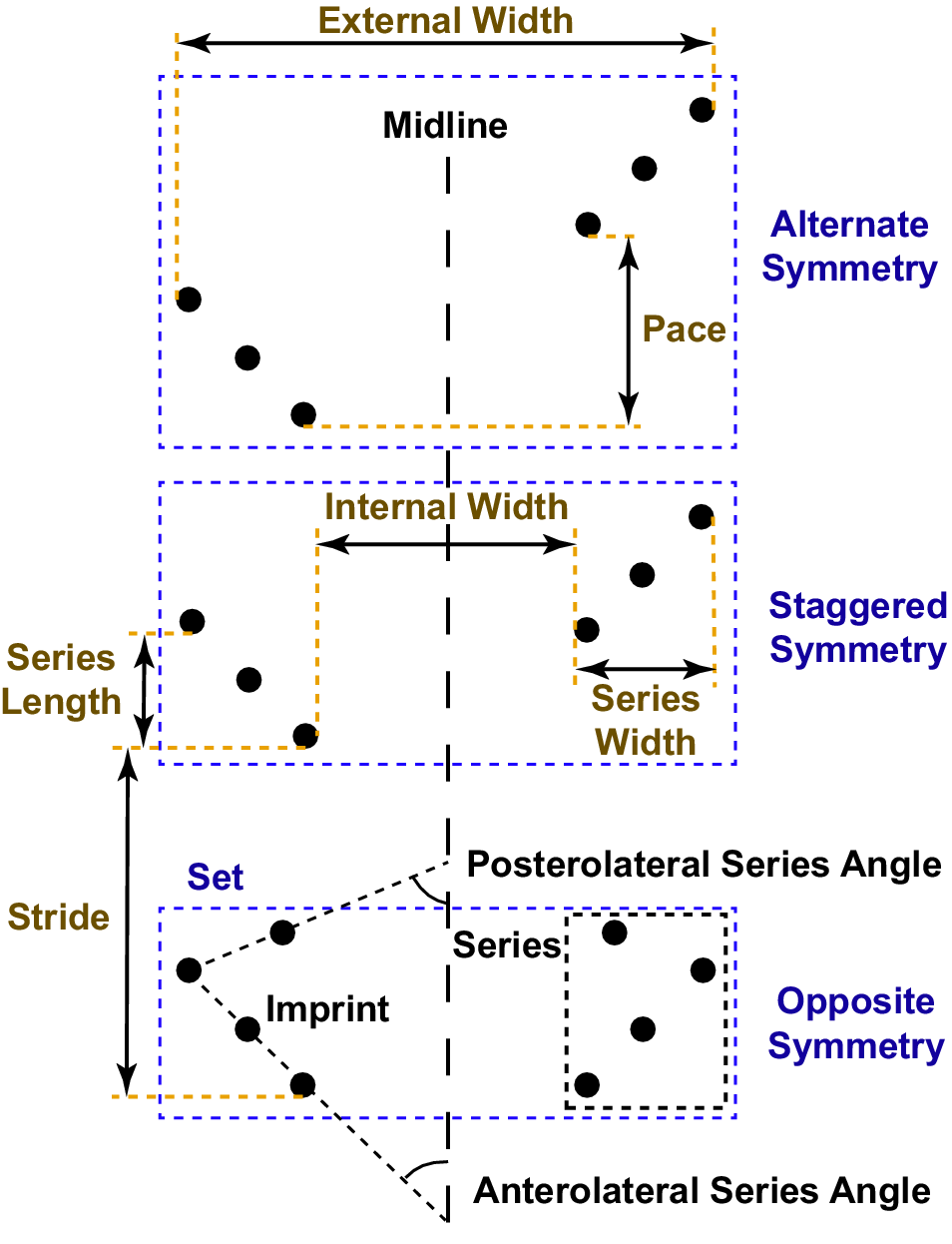

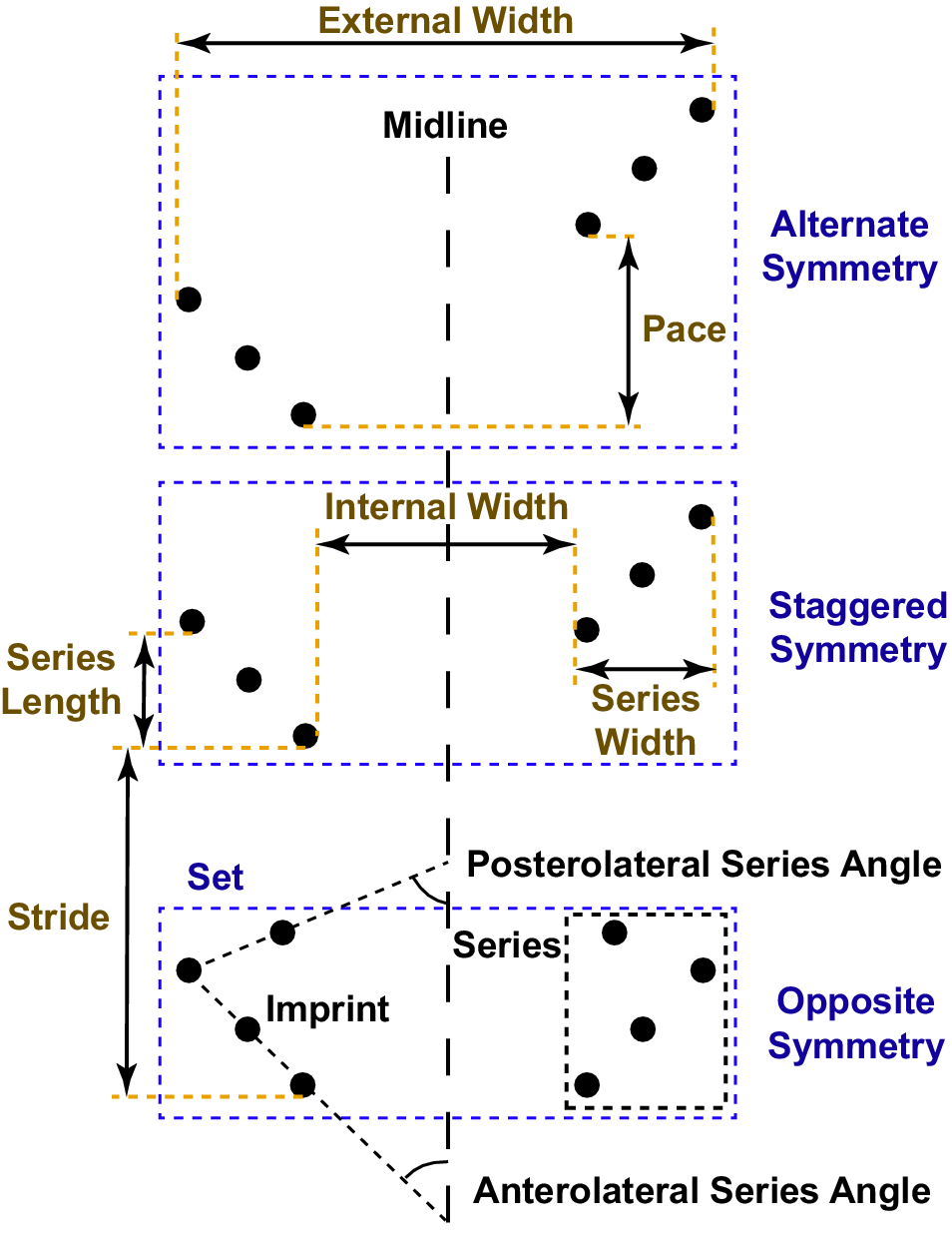

The terminology used to describe the trackway follows that proposed by Trewin (Reference Trewin1994) and modified by Minter et al. (Reference Minter, Braddy and Davis2007; Fig. 4). An arthropod trackway consists of multiple track series (imprints of all the limbs on one side of the body). Series length is measured parallel to the trackway midline and series width perpendicular to the midline. Two track series on opposite sides of the midline formed during a single locomotor cycle make up a track set.

Figure 4. Schematic diagram of an arthropod trackway, illustrating the descriptive terminology used in this study (modified from Minter et al., Reference Minter, Braddy and Davis2007). Four pairs of walking legs contact the substrate in the bottom track set, but only three make contact in the middle and top track sets. Stride varies widely among the three track sets, resulting in different modes of track series symmetry across the midline.

Stride is the distance parallel to the midline between two consecutive tracks made by the same specific limb, corresponding to the distance moved in the direction of travel during a locomotor cycle. Pace is the distance parallel to the midline between tracks in the same set made by corresponding limbs on opposite sides of the body, such as the posteriormost right limb and the posteriormost left limb. The rows of series are said to display opposite symmetry if pace ≈ 0, staggered symmetry if the pace is approximately one-half of the stride length, and alternate symmetry for anything in between. The internal and external widths of a set are measured perpendicular to the midline, as the distances between the innermost and outermost tracks in the two series making up the set.

A less widely used morphological characteristic is the series angle, which can be measured when the tracks belonging to each series fall approximately on a straight line. Series angle is then the angle between the track series line and the trackway midline, with acute angles indicating that the track series line extends anterolaterally from the trackway midline and obtuse angles indicating that the line extends posterolaterally. If a series of three or more tracks forms an “L-shape” because at least one track at the beginning or end of the series is offset from the others, both posterior and anterior series angles can be measured using the lines formed by the posterior and anterior groups of imprints (Fig. 4). Neither Trewin (Reference Trewin1994) nor Minter et al. (Reference Minter, Braddy and Davis2007) formally defined a term to describe these angles, but researchers have used “angle converging/diverging to/from the direction of travel” (cf. Sadler, Reference Sadler1993) or “anterolateral” and “posterolateral” angles (Minter and Braddy, Reference Minter and Braddy2009). However, track imprints do not always form straight lines or a clear L-shapes, so angle measurements are frequently unfeasible, and the inconsistent naming scheme for trackways consisting of ‘L-shaped’ series may have led to some confusion in ichnotaxonomy (discussed in the following). In the Wapiti Formation trackways, the positioning and even the number of the preserved imprints shows considerable variation among series, complicating angle measurements and making them inconsistent. Accordingly, these measurements were not taken in the present analysis.

Repositories and institutional abbreviations

UALVP: University of Alberta Laboratory for Vertebrate Palaeontology, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; UA T: University of Alberta Museums Trace Fossil Collection, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Systematic ichnology

Ichnogenus Octopodichnus Gilmore, Reference Gilmore1927

Type ichnospecies

Octopodichnus didactylus Gilmore, Reference Gilmore1927.

Other ichnospecies

Octopodichnus minor, Brady, Reference Brady1947; Octopodichnus raymondi Sadler, Reference Sadler1993.

Diagnosis

The trackway of an eight-footed animal with impressions arranged in alternating groups of four; individual terminal appendage imprints circular to oval or have more complex bifid or trifid forms. After Sadler, Reference Sadler1993.

Octopodichnus cf. O. raymondi Sadler, Reference Sadler1993

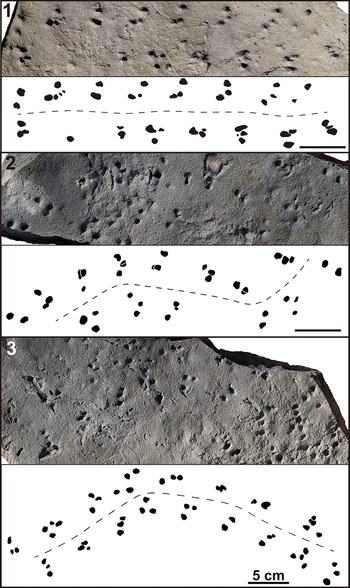

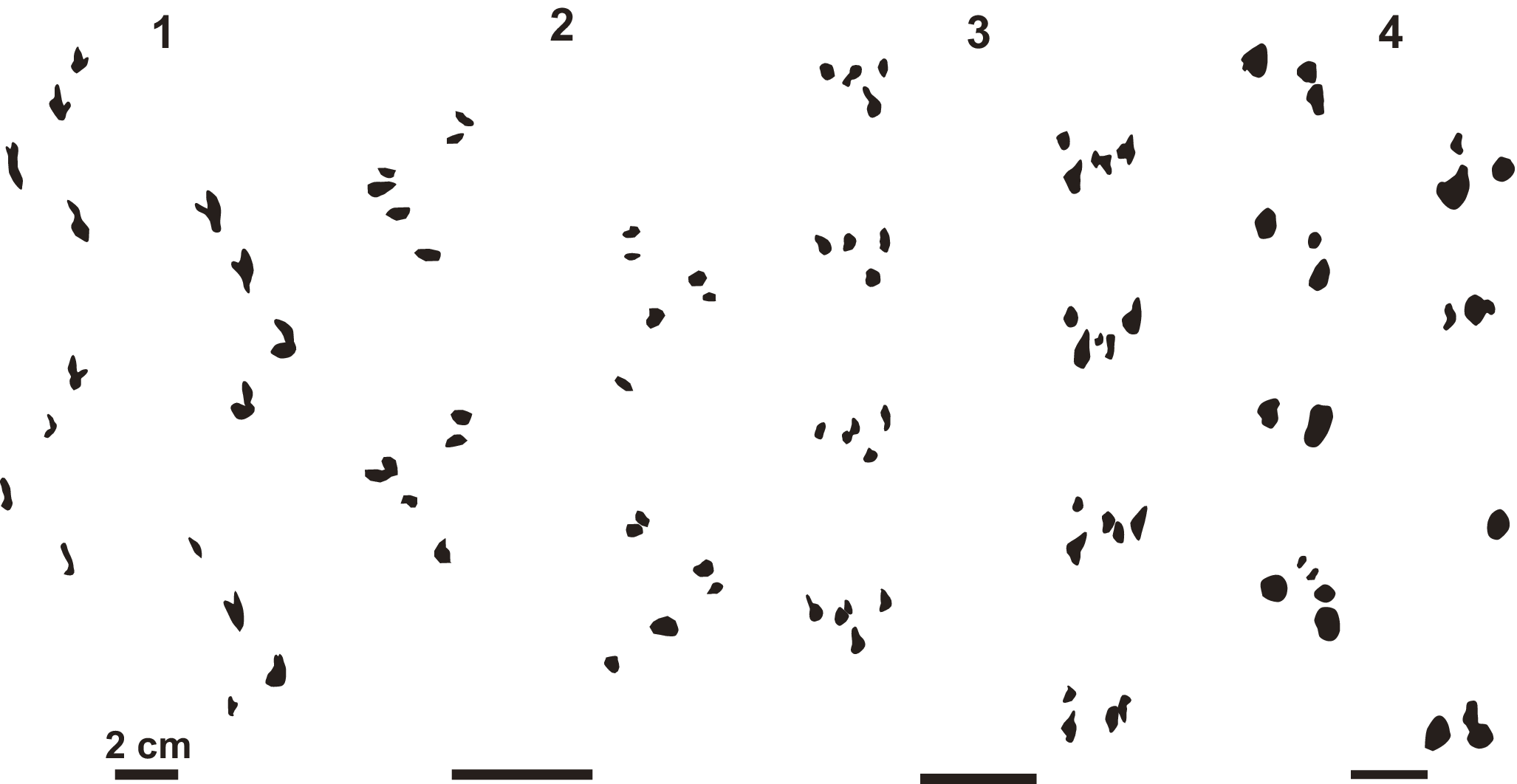

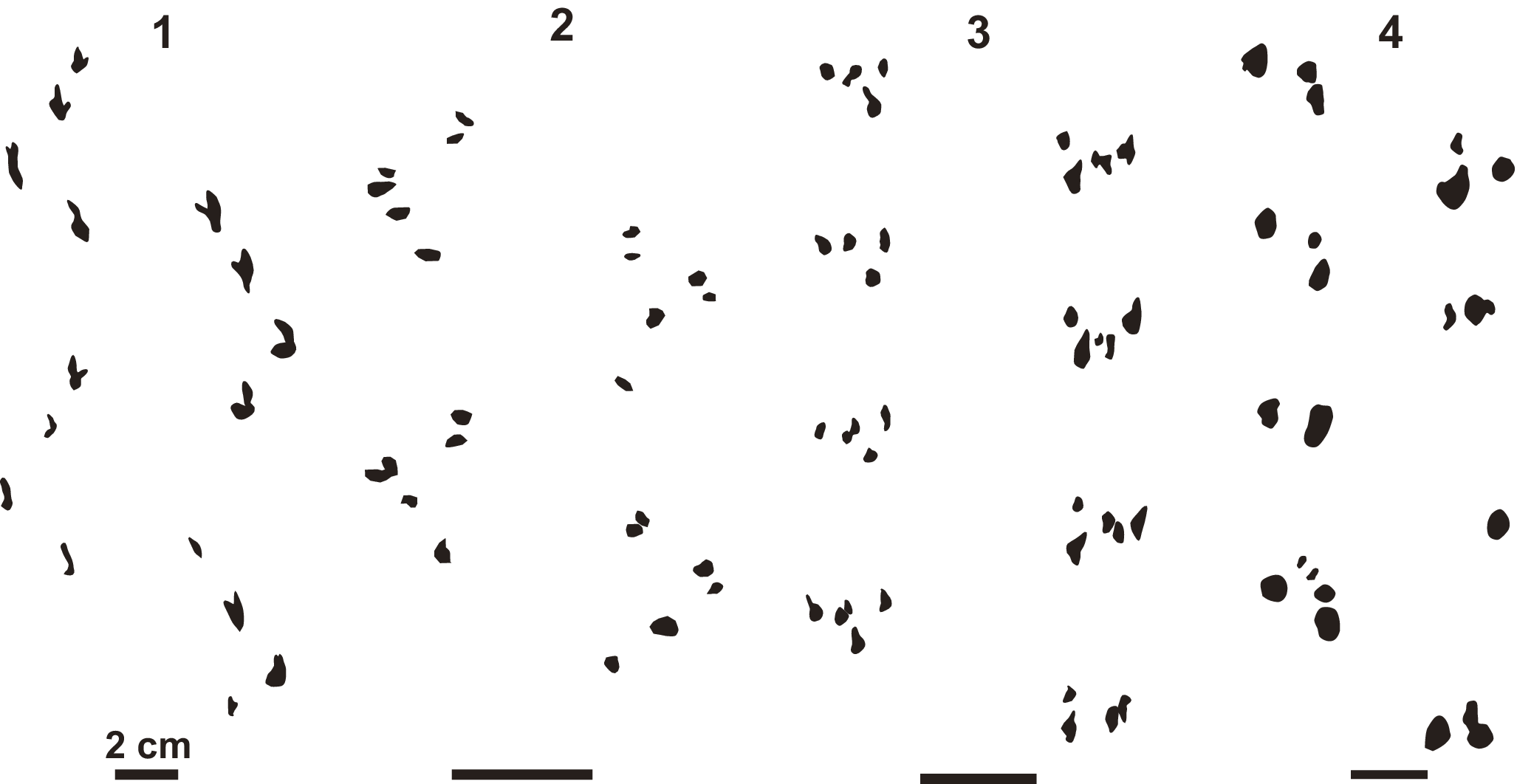

Figure 5. Epichnial view of Octopodichnus cf. O. raymondi with interpretive line drawings. Note that the dashed line represents the midline of the trackway rather than an actual medial impression. For all trackways, the direction of movement is interpreted to be from the left to the right of the image. (1) Rectilinear trackway on UALVP 62351 consisting of 16 track series (TW1). The total length of the trackway is approximately 35 cm. (2) S-shaped trackway on UA T119 consisting of 14 track series (TW2). The total length of the trackway is approximately 33 cm. (3) Curved trackway on UA T120 consisting of 17 track series (TW3). The total length of the trackway is approximately 43 cm. The other trackway on UA T120 (TW4) starts from the bottom right of the image and overlaps with the curved trackway near the top of the image but has been omitted from the drawing for clarity. Scale bars = 5 cm.

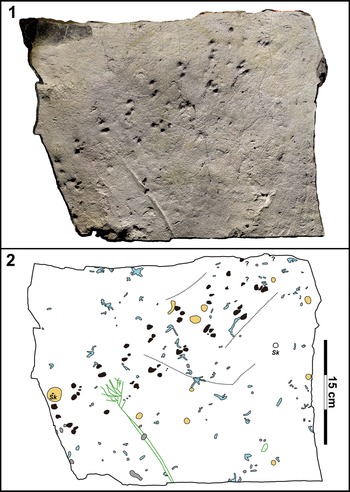

Figure 6. Representative mudstone block (UALVP 62351) bearing invertebrate trace fossils. (1) Photogrammetric model of the mudstone slab viewed from above. (2) Interpretive line drawing of the invertebrate trace fossils on the mudstone slab. The trackway fossil described in this paper is shaded in black while isolated arthropod tracks are shaded in gray, subhorizontal backfilled burrows in light blue, and areas containing fecal matter in yellow. Two unfilled Skolithos Haldeman, Reference Haldeman1840 are indicated by “Sk.” Three surface trails are traced in dashed lines. Green lines indicate outlines of large, silicified plant fragments on the slab surface.

Materials

One continuous trackway consisting of 16 track sets on UALVP 62351 (hereafter referred to as TW1); one continuous (TW2) and one partial trackway consisting of 14 and 10 track sets, respectively, on UA T119; two continuous trackways (TW3 and TW4) consisting of 17 and 7 track sets, respectively, on UA T120.

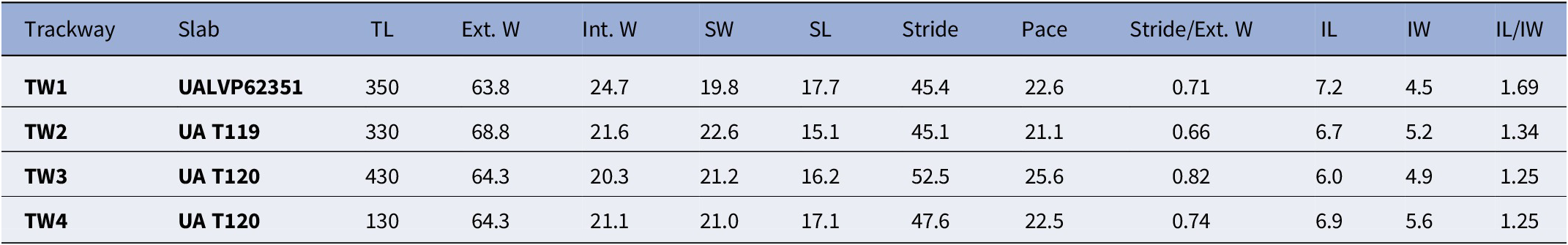

Description

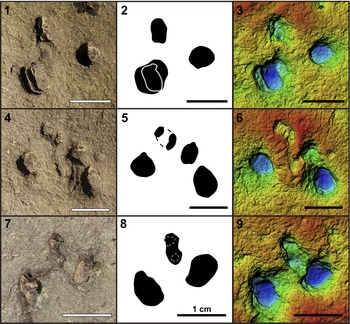

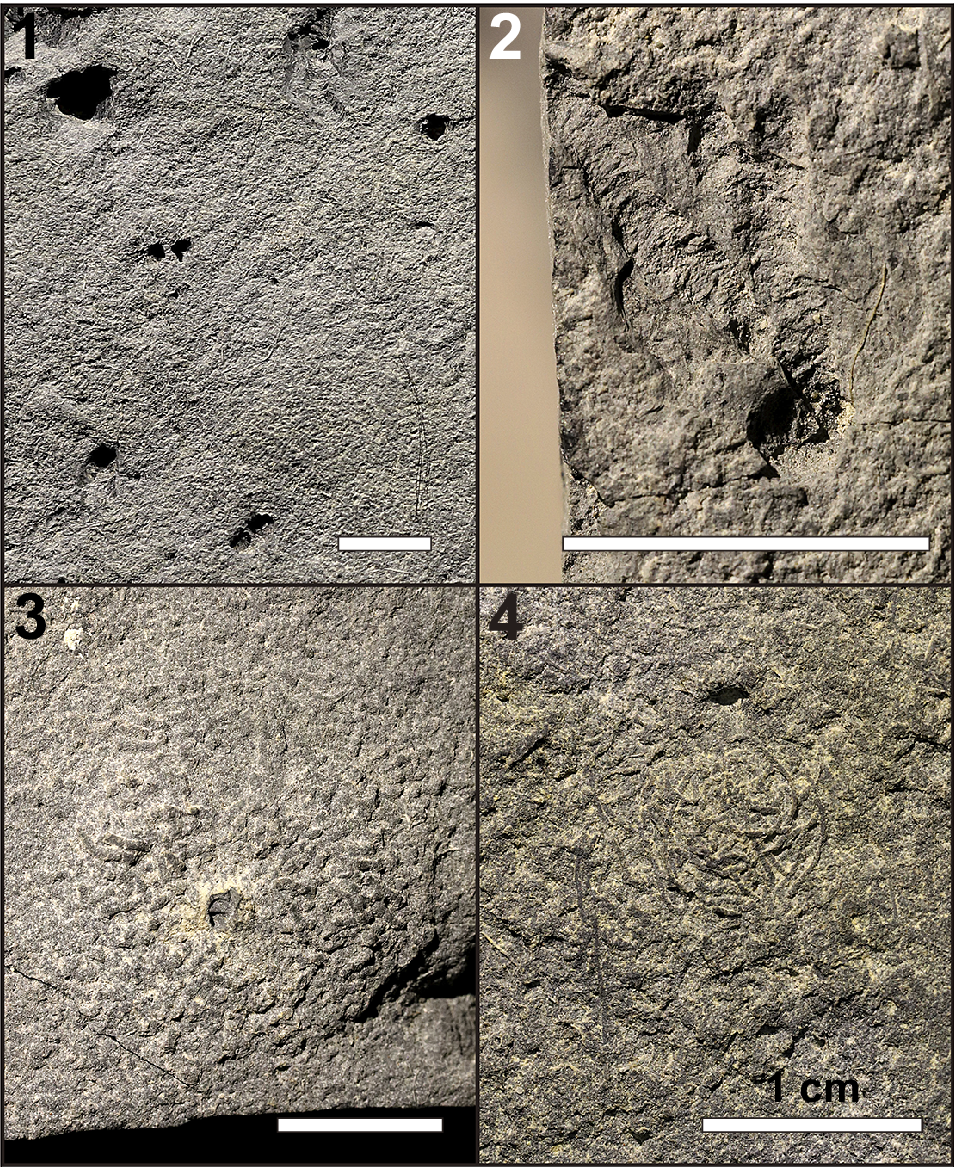

Each of the four trackways (TW1–TW4) consists of two parallel rows of track series with staggered to alternate symmetry (Figs. 5, 6). Trackways are straight to sinuous, with total preserved lengths ranging from 13 to 43 cm, and consist of 7 to 17 track sets preserved in concave epirelief. The average external widths of the trackways range from 64.3 to 68.8 mm whereas the average internal widths are 20.3–24.7 mm (Table 1). The average strides are 45.1–52.5 mm, and the average paces are 21.1–25.6 mm. These values result in stride-to-external-width ratios of 66% to 82%. Notably, extra track series are frequently evident on the outer sides of curves in the trackway as the trackmaker took an additional step with the limbs on the corresponding side of the body to compensate for the greater distance traveled. No medial impressions are preserved. Most track series consist of three track imprints, but the number ranges from one to four, and some tracks were overprinted by other limbs of the trackmaker (Fig. 7.1–7.3). Average series widths are 19.8–22.6 mm, and average series lengths are 15.1–17.7 mm (Table 1). Track emplacement is somewhat random, with no consistent spatial arrangement among the imprints in a given series. In series of three tracks, for example, the imprints may form a straight line, an equilateral triangle, or some intermediate configuration. In many series, the outermost imprint is situated farther anteriorly than the innermost imprint, while in other cases the outermost imprint is the more posteriorly situated. The imprints are elliptical, sometimes with tapering anterior ends, and the imprints are typically 4.5–5.5 mm wide, 6–7 mm long, and 3–5 mm deep (Fig. 7). Some imprints show bifurcation (Fig. 7.4–7.9). The deepest part of each track is flattened or displays a low push-back ridge. The imprints vary in size within each series, the inner- and/or outermost ones usually being the largest (Fig. 7).

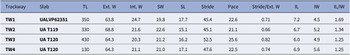

Table 1. Summary of trackway measurements. TL = total length; Ext. W = external width; Int. W = internal width; SW = series width; SL = series length; IL = imprint length; IW = imprint width. Values are reported in millimeters except for Stride/Ext. W and IL/IW (which are ratios)

Figure 7. Close-up of representative track series on TW1. The tracemaker direction of movement is interpreted to be from the bottom to the top in all images. The left column shows a photo of each track series, the middle column an interpretive drawing, and the right column a digital elevation model (DEM). The contour lines on the DEMs represent 1 mm of elevation. (1–3) Track series showing overstepping of the lower left imprint. (4–6) Four track imprints, including one that is clearly bifurcated. (7–9) Track series in which the posterior two imprints are much larger and deeper than the anterior imprint. Note also that the anterior imprint is faintly bifurcated. Scale bars = 1 cm.

Remarks

Several ichnotaxa attributed to arthropods are similar to the trace fossils described herein: Octopodichnus, Paleohelcura, Palmichnium, Siskemia, and Stiaria. Among these, Palmichnium consists of two rows of track series, each with three to five imprints (emended by Braddy and Gass, Reference Braddy and Gass2023). However, the series are usually registered in opposite symmetry, which contrasts with the staggered to alternate symmetry of the Wapiti trackway. While Palmichnium may occasionally exhibit staggered or even alternate symmetry, they are also considerably larger, with external widths typically on the order of hundreds of millimeters (Briggs and Rolfe, Reference Briggs and Rolfe1983; Draganits et al., Reference Draganits, Braddy and Briggs2001; Braddy and Gass, Reference Braddy and Gass2023). It is also worth noting that the imprints in each series of Palmichnium are usually well and regularly spaced and form a near-perfect line that may be slightly curved (e.g., Briggs and Rolfe, Reference Briggs and Rolfe1983; Draganits et al., Reference Draganits, Braddy and Briggs2001; Braddy and Gass, Reference Braddy and Gass2023), whereas the trackways from the Wapiti Formation suggest less regular limb placement.

Stiaria is a purported arthropod trackway with a single medial groove running between two rows of track series (Smith, Reference Smith1909; emended by Walker, Reference Walker1985). Stiaria quadripedia Smith, Reference Smith1909 can have up to four track imprints in a series (Walker, Reference Walker1985), similar to the trackways from the Wapiti Formation. The presence or absence of the medial groove in other Stiaria species, such as S. intermedia (Smith, Reference Smith1909), is regarded as minor morphological variation (e.g., Lucas et al., Reference Lucas, Minter, Spielmann, Smith, Braddy, Lucas, Zeigler and Spielmann2005; Minter and Braddy, Reference Minter and Braddy2009; Getty et al., Reference Getty, Sproule, Wagner and Bush2013). However, the applicability of whether the presence of a medial groove should be considered a minor morphological feature in S. quadripedia has not yet been widely discussed. In fact, the presence of the medial groove remains one of the key characteristics that differentiates S. quadripedia from Octopodichnus isp. and should be retained as a diagnostic trait unless compelling evidence is presented for synonymizing the two ichnotaxa. Hence, the complete lack of a medial impression in the Wapiti Formation trackways is enough to reject an assignment to Stiaria. The same applies to Siskemia Smith, Reference Smith1909, which features similarly patterned rows of track series on either side of two parallel medial impressions, rather than just one (Walker, Reference Walker1985).

Paleohelcura is another arthropod trackway ichnotaxon named for two parallel rows of track series consisting of three to four sets of imprints in alternate to staggered symmetry, with or without a medial imprint (Gilmore, Reference Gilmore1926; Peixoto et al., Reference de Peixoto, Mángano, Minter, Dos Reis Fernandes and Fernandes2020). While the original diagnosis of Paleohelcura included the presence of only three leg imprints per series, subsequent studies have included specimens with up to four tracks in a series (e.g., Lucas et al., Reference Lucas, Lerner, Bruner and Shipman2004). Lucas et al. (Reference Lucas, Lerner, Bruner and Shipman2004) noted that their specimen of Paleohelcura tridactyla had some differences from the holotype, including a shorter stride, a lower average stride-to-width ratio, and the intermittent occurrence of a fourth impression. The most recently emended diagnosis of Paleohelcura by Peixoto et al. (Reference de Peixoto, Mángano, Minter, Dos Reis Fernandes and Fernandes2020) includes up to four track imprints per series; however, this was challenged by Clendenon (Reference Clendenon2024) and Clendenon and Brand (Reference Clendenon and Brand2024). They contended that the fourth leg imprint was initially a misinterpretation by Brady (Reference Brady1947: p. 466), who stated “…one foot group showed a clear impression of a fourth foot on one side”, and suggested that the supposed fourth imprint more likely represents a background depression. We concur with Clendenon (Reference Clendenon2024) and Clendenon and Brand (Reference Clendenon and Brand2024) that arthropod trackways with four imprints per series should be identified as Octopodichnus isp. or S. quadripedia rather than Paleohelcura. The number of digit imprints, and their arrangement, are fundamental ichnotaxobases for purported arthropod-generated traces. Therefore, the distinctively eight-footed trackways from the Wapiti Formation cannot be classified as Paleohelcura. Both Octopodichnus and Paleohelcura should be considered valid ichnogenera.

Octopodichnus is a name for trackways produced by eight-footed arthropods (Gilmore, Reference Gilmore1927) and includes the type ichnospecies O. didactylus Gilmore, Reference Gilmore1927 together with O. minor Brady, Reference Brady1947 and O. raymondi Sadler, Reference Sadler1993, all of which are diagnosed primarily on the morphological arrangement of the imprints (Fig. 8). A fourth ichnospecies, O. minimus, was proposed by Kozur and Lemone (Reference Kozur, Lemone, Lucas and Heckert1995); however, Minter and Braddy (Reference Minter and Braddy2009) regarded this taxon as a nomen dubium because the ichnospecies was based on a single partial specimen that could not be clearly differentiated from other Octopodichnus ichnospecies. It is also worth noting that some researchers (Minter and Braddy, Reference Minter and Braddy2009; Lockley et al., Reference Lockley, Tedrow, Chamberlain, Minter, Lim, Sullivan, Lucas and Spielmann2011) have hinted that O. raymondi should be a junior synonym of P. tridactyla Gilmore, Reference Gilmore1926. This is based on the speculation that Sadler (Reference Sadler1993) may have assigned the trackway to Octopodichnus because of a previous notion by Briggs and Rolfe (Reference Briggs and Rolfe1983) describing the specimen (originally described by Alf, Reference Alf1968) being similar to Octopodichnus, combined with the possibility that Sadler inferred the trackmaker to have been an arachnid. However, as discussed earlier, the distinctively eight-footed nature of O. raymondi rules out synonymy with P. tridactyla.

Figure 8. Comparison of different ichnospecies of Octopodichnus with the trackway from the Wapiti Formation. (1) Type specimen of Octopodichnus didactylus (MNA N9393; MNA = Museum of Northern Arizona). (2) Type specimen of Octopodichnus minor (MNA N3654). (3) Type specimen of Octopodichnus raymondi (RAM 139; RAM = Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology). (4) Octopodichnus cf. O. raymondi (this study). The direction of movement of the tracemakers in all cases is from bottom to top. Note that the images are not to scale. The holotypes are redrawn from Minter and Braddy (Reference Minter and Braddy2009) and Lockley et al. (Reference Lockley, Tedrow, Chamberlain, Minter, Lim, Sullivan, Lucas and Spielmann2011). Scale bars = 2 cm.

Octopodichnus didactylus is characterized by having the three anterior imprints in each series of four arranged in an anteromedially oriented line, forming a posterolateral series angle (i.e., the angle between the anterior three imprints and the midline) of 45°. By contrast, O. minor has the posterior three tracks arranged in a posteromedially oriented line with an anterolateral series angle of 35° to 40°. Leg placement is less regular in O. raymondi, but Sadler (Reference Sadler1993) diagnosed the species in part because of the anterior three imprints in each series being angled “inward at 50 to 90°” (Sadler, Reference Sadler1993, p. 245), which translates to a posterolateral series angle of 50° to 90°. In addition, the strides of the trackway are shorter in O. raymondi compared with other ichnospecies (Fig. 8), which results in a relatively smaller stride-to-width ratio of 0.62 (compared with 1.14 in O. didactylus and 0.91 in O. minor; Sadler, Reference Sadler1993). Moreover, within each series, the imprints of O. raymondi are emplaced about the same position with respect to the direction of travel, resulting in a small series-length-to-series-width ratio. Although these measurements are not readily available in the literature, judging from the images of the type specimens of each ichnospecies, O. didactylus and O. minor have consistently longer series lengths with respect to series widths (series lengths of 65.5 mm and 22.2 mm compared with series widths of 30.1 mm and 14.9 mm, respectively), whereas the opposite is the case for O. raymondi (series length of 10.8 mm and series width of 13.6 mm).

Braddy (Reference Braddy, Lucas and Heckert1995) misinterpreted Sadler’s diagnosis by mistaking what was intended to be a posterolateral series angle with the anterolateral series angle. He further argued that the difference in series length between O. minor and O. raymondi could be due to minor variations reflecting different walking speeds of the same trackmaker, implying a need for synonymization of the two ichnotaxa; we disagree with the synonymization. The holotype of O. raymondi appears to consistently have the anterior three imprints in line in track series on the left side of the midline, whereas it is the posterior three imprints that are in line in the right row of track series. This is in sharp contrast with O. didactylus and O. minor, in which the well-spaced imprints make it clear which track imprints are in a straight line. It is this rather ambiguous imprint pattern that sets O. raymondi apart from the other Octopodichnus ichnospecies, in combination with a low series length-to-width ratio, and it is our opinion that O. raymondi should not be synonymized with either O. didactylus or O. minor. Ideally, measurable variables should be formulated to capture the difference in track arrangement, but this would require reanalysis of Octopodichnus specimens, which is beyond the scope of this study.

The arthropod trackway described herein is characterized by up to four track imprints per series, consistent with Octopodichnus. However, the frequent overstepping or complete absence of one of the four imprints makes it difficult to measure the series angle necessary to definitively assign it to an ichnospecies. It is also worth noting that digit placement is also inconsistent within and between the trackways, which adds to the complexity of assigning an ichnospecies. Therefore, it is not possible to determine the ichnospecies on this basis. The track series of the Wapiti Formation trackways appear to be more closely clustered than is the case in O. didactylus and O. minor, which is reflected in a low stride-to-external-width ratio (0.69–0.82) and a consistently shorter average series length (15.1–17.7 mm) with respect to average series width (19.8–24.7 mm). The stride-to-external-width ratio is slightly larger than that of the type specimen of O. raymondi (0.62; Sadler, Reference Sadler1993) but smaller than those of the other two ichnospecies. The trackways described herein most resemble O. raymondi, but without the measurements of the series angle, this assignment is tentative. Hence, the trackways are referred to Octopodichnus cf. O. raymondi.

Examples of Octopodichnus (including the type specimens of all three ichnospecies) have principally been reported from Permian aeolianites (e.g., Gilmore, Reference Gilmore1927; Brady, Reference Brady1947; Sadler, Reference Sadler1993), although an earlier occurrence has been suggested from the Carboniferous (albeit without a detailed description; Knecht et al., Reference Knecht, Benner, Swain, Azevedo-Schmidt and Cleal2024). Cretaceous examples are known from aeolianites of Argentina and Brazil (e.g., Francischini et al., Reference Francischini, Fernandes, Kunzler, Rodrigues, Leonardi and de Souza Carvalho2020; Melchor et al., Reference Melchor, Perez and Umazano2024) and floodplain or coastal plain deposits of the United States (Shibata and Varricchio, Reference Shibata and Varricchio2020). In more recent deposits, Octopodichnus trackways have been identified from Miocene and Pleistocene aeolianites (Lockley et al., Reference Lockley, Culver, Wegweiser, Lucas, Spielmann and Lockley2007, Reference Lockley, Helm, Cawthra, De Vynck, Dixon and Venter2022). Several modern analogs have also been produced through neoichnological experiments using tarantulas and scorpions (e.g., Sadler, Reference Sadler1993; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Minter and Braddy2007; Clendenon and Brand, Reference Clendenon and Brand2023).

Results

Other biogenic sedimentary structures

In addition to the trackways described, isolated invertebrate tracks, vertical burrows, radiating meniscate burrows, surficial trails or scratch marks, and fecal mounds are found on the surfaces of the mudstone slabs (Fig. 6). The isolated tracks each comprise 1–4 (but usually 1 or 2) leg imprints, some being similar in size to the series in the main described trackways and others significantly smaller (Fig. 9.1). The track marks are identified by their curled margins (from sediment deformation) and flat and compacted bases, and/or the presence of a leg drag mark on one side of a given imprint.

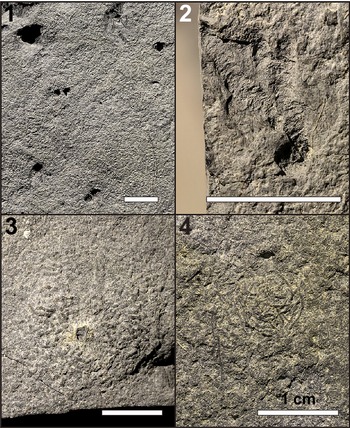

Figure 9. Invertebrate trace fossils present on UALVP 62351. (1) Isolated arthropod tracks. The leg imprint at the top left corner belongs to one of the series making up TW1. Note that many of the imprints are bifurcated rather than single. (2) Radiating, backfilled, subhorizontal burrows. Note that the burrows extend from a single vertical shaft situated near the bottom of the image. (3) Fecal mound with a vertical burrow in the center. The fecal pellets making up the mound are short and oriented randomly around the central burrow. (4) Fecal strings, thinner and longer than the pellets in the fecal mounds. The strings are coiled and do not form a mound. Scale bars = 1 cm.

The surface trails (or scratch marks) are shallow grooves that resemble Helminthoidichnites Fitch, Reference Fitch1850, three of which can be seen on UALVP 62351 (Fig. 6). Two of them extend parallel to the long axis of TW1 on different sides of the trackway, lateral to the leg imprints, and measure 110 mm and 70 mm long. The other impression is longer (184 mm) and bends midway: it originates (or terminates) approximately at the midline of the trackway and initially extends almost perpendicular to the trackway, then turns sharply to parallel the other impressions. The impressions are straight and neither curve nor meander nor loop.

Two types of burrows are found on the slab surface: vertical burrows and radiating burrows. The vertical burrows appear to have been passively filled and are simple in morphology, consistent with Skolithos Haldeman, Reference Haldeman1840. Two vertical burrows were observed, one with a diameter of 6.5 mm and the other with a diameter of ~2 mm. The latter runs through the center of a fecal mound (Fig. 9.3). The radiating burrows consist of multiple subhorizontal shafts originating from a vertical shaft (different from the Skolithos described in the preceding) in the center (Fig. 9.2). Many of these burrows lack the outer burrow wall, and the internal wall can be seen to bear annulations, which are likely remnants of meniscate backfills. The backfills occasionally include white mineral grains, which are likely derived from the overlying bentonite. The burrows range from 1.0 to 4.5 mm in diameter and are up to 18 mm long. The radiating burrows typically trend in similar directions and are usually confined within a 90° arc (although there are some cases where a few shafts extend in the opposite direction). Notably, none of the burrows exhibits any branching. While several radiating burrow ichnotaxa have been named (cf. Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Mángano and Buatois2019; Harris et al., Reference Harris, Olariu, Melnyk, LaGrange, Konhauser and Gingras2024), the burrows from the Wapiti Formation cannot be confidently assigned to any existing ichnotaxon.

Finally, the bedding surface bears small fecal pellets that are ~0.5 mm in diameter. The fecal material has a similar composition to the host rock. Some pellets are piled up in confined areas 1–2 cm in diameter (Fig. 9.3). The pellets are variably oriented and usually short (2–5 mm long) although some take the form of long strands that are curved to coiled (1.0–1.5 cm; Fig. 9.4). At least 18 fecal mounds were found across the three slabs.

Discussion

Taphonomic interpretations

The exquisite preservation of the trace fossils described in this paper demands a taphonomic explanation. Here we infer that the bentonitic overlying layer may have contributed to this phenomenon. Preservation of arthropod trackways is greatly improved by (1) lithologic contrast and/or the presence of a film (such as a mucous layer or biomat) between the substrate and casting material, (2) non-erosional deposition or rapid burial in the waning stages of a storm or flood event, and/or (3) formation of undertracks that penetrate deep into the substrate (Seilacher, Reference Seilacher2008). Therefore, the lithological contrast between the floodplain mud and the overlying ash was favorable for preserving surficial features. Ash fall is also an entirely non-erosional process that could rapidly have buried arthropod trackways along with other fine animal traces—such as fecal mounds—without disturbing them. Moreover, volcanic ash fall would have detrimentally impacted the contemporaneous biota (cf. Carrillo and Díaz-Villanueva, Reference Carrillo and Díaz-Villanueva2021), protecting the traces against bioturbation by inhibiting shallow-tier burrowers from reaching the underlying muds. Some deep-tier burrowers, however, may have colonized the bed after the ash fall to mine organic matter, producing the radiating burrows (discussed in the following).

Associated trace fossils

Invertebrate trace fossils other than Octopodichnus cf. O. raymondi preserved on the trackway-bearing slabs include simple vertical burrows (Skolithos isp.), radiating subhorizontal burrows with backfills, and fecal mounds. These structures are distinctive, were produced by tracemakers other than those that produced the trackway, and merit future taxonomic evaluation. However, only a brief discussion is provided herein. The vertical burrows lack distinct linings or fills, which are features consistent with Skolithos. One of the burrows is associated with a fecal mound, and similar mounds are found all over the surface of the rock slabs. Similar fecal mounds are commonly produced by annelids. For example, fecal mounds produced by arenicolid worms (Cumulusichnus asturiensis Mángano et al., Reference Mángano, Buatois, Piñuela, Volkenborn, Rodríguez-Tovar and García-Ramos2024) were recently described from Jurassic delta plain deposits of the Lastres Formation of Spain. In modern terrestrial settings, some earthworm species are known to produce fecal mounds (casts), although we are not aware of well-described fossil examples. However, Edaphichnium Bown and Kraus, Reference Bown and Kraus1983 are pellet-filled earthworm burrows (e.g., Smith et al., Reference Smith, Hasiotis, Kraus and Woody2008). In subaqueous non-marine settings, tubificid worms are known to produce similar fecal mounds (cf. Dafoe et al., Reference Dafoe, Rygh, Yang, Gingras and Pemberton2011). Fossil pellet mounds in fluvio–lacustrine successions were reported from the Eocene Green River Formation of the United States, although they were not described in detail (Bohacs et al., Reference Bohacs, Hasiotis and Demko2007).

The radiating subhorizontal burrows are similar in diameter to the central burrow shaft of the fecal mound and were likely produced by similar, if not identical, tracemakers. The size of the burrows and their internal structure (annulations that most likely resulted from meniscate backfills) make them resemble Taenidium barreti (Bradshaw, Reference Bradshaw1981) specimens from Oligocene fluvio–lacustrine deposits in Spain (de Gibert and Sáez, Reference de Gibert and Sáez2009, p. 167, fig. 4E, F). However, the specimens from Spain are straight to curved and do not radiate like those described here. In fact, Taenidium do not exhibit true branching, much less radiate from a single point (D’Alessandro and Bromley, Reference D’Alessandro and Bromley1987; Keighley and Pickerill, Reference Keighley and Pickerill1994). Annulated moniliform burrows that radiate from a single point have recently been identified from late Miocene lacustrine deposits in Iceland and were given the name Thorichnus ramosus Pokorný et al., Reference Pokorný, Krmíček and Sudo2017. While the burrow sizes and morphologies are similar to the ones described here, T. ramosus are diagnosed by primary branching, which is absent in the radiating burrows from the Wapiti Formation. Other similarly radiating backfilled burrows include mining structures such as Cladichnus D’Alessandro and Bromley, Reference D’Alessandro and Bromley1987 and Skolichnus Uchman, Reference Uchman2010 (e.g., Wetzel and Uchman, Reference Wetzel and Uchman2013), although these tend to have more numerous rays, primarily successively branched, and shafts that radiate according to a more regular pattern. These structures (usually found in marine settings) are thought to represent structures formed during food mining under unfavorable local geochemistry (particularly anoxic substrate conditions; e.g., Wetzel and Uchman, Reference Wetzel and Uchman2013), whereas in the case of the Wapiti Formation specimens, the radiating burrows would have been used to access food that was available only beneath the volcanic ash. This is also evidenced by occasionally present bentonites that form burrow infills. Terrestrial anecic worms produce vertical shafts that may have branched endings (Genise, Reference Genise2017), while in subaqueous settings, modern tubificid worms occasionally burrow into sandy substrates (Dafoe et al., Reference Dafoe, Rygh, Yang, Gingras and Pemberton2011), and chironomid larvae can produce deep (≤34 cm) burrows with branched endings (Gingras et al., Reference Gingras, Lalond, Amskold and Konhauser2007) within loosely compacted, subaqueous sediment.

Interpretations of the arthropod trackway

The presence of three to four leg imprints in each track series indicates that the trackways from the Wapiti Formation represent walking traces (repichnia) of an arthropod with at least four sets of walking appendages. Such trace fossils have been found principally in Permian rocks and are commonly inferred to have been produced by arachnids, typically tarantulas and sometimes scorpions (e.g., Brady, Reference Brady1947; Lockley et al., Reference Lockley, Culver, Wegweiser, Lucas, Spielmann and Lockley2007; Chure et al., Reference Chure, Good, Engelmann, Lockley and Lucas2014; Good and Ekdale, Reference Good and Ekdale2014), and neoichnological studies support these interpretations (e.g., Brady, Reference Brady1939; Alf, Reference Alf1968; Sadler, Reference Sadler1993; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Minter and Braddy2007; Abbassi and Mustoe, Reference Abbassi and Mustoe2018; Clendenon and Brand, Reference Clendenon and Brand2023). However, our interpretation of the depositional environment as swampy is inconsistent with the typical habitat of modern exemplars of these arthropod groups. Most modern scorpions and tarantulas are found in deserts, grasslands, and forests (Williams, Reference Williams1987; Lourenço, Reference Lourenço, Gopalakrishnakone, Possani, Schwartz and Rodríguez de la Vega2015). Indeed, with few exceptions (e.g., tidal flat sandstone, Minter and Braddy, Reference Minter and Braddy2009; channel overbank or coastal plain deposit, Shibata and Varricchio, Reference Shibata and Varricchio2020), most Octopodichnus specimens are found in sandstone successions interpreted as aeolian dune deposits (e.g., Brady, Reference Brady1947; Lockley et al., Reference Lockley, Tedrow, Chamberlain, Minter, Lim, Sullivan, Lucas and Spielmann2011; Good and Ekdale, Reference Good and Ekdale2014). Although rivers may cut through arid habitats and create localized swampy areas that arthropods may enter incidentally, the abundance of the trackways described herein suggests that they were likely produced by a permanent resident of the swampy paleoenvironments typical of the Wapiti Formation Unit 3 (Fanti and Catuneanu, Reference Fanti and Catuneanu2009; Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Bell, Vavrek, Larson, Koppelhus, Sissons, Langone, Campione and Sullivan2022).

The paleoclimate of the Wapiti Formation alluvial plain is equally inconsistent with the typical geographical distribution of modern scorpions and tarantulas. Although the paleoclimate has yet to be described in detail (cf. Koppelhus and Fanti, Reference Koppelhus and Fanti2019), the area is calculated to be situated at ~62°N paleolatitude (according to the online paleolatitude calculator of van Hinsbergen et al., Reference van Hinsbergen, De Groot, van Schaik, Spakman, Bijl, Sluijs, Langereis and Brinkhuis2015), and the environment has been interpreted as a northern temperate one (e.g., Fanti and Miyashita, Reference Fanti and Miyashita2009; Fanti et al., Reference Fanti, Bell and Sissons2013, Reference Fanti, Bell, Vavrek, Larson, Koppelhus, Sissons, Langone, Campione and Sullivan2022). In North America, temporally equivalent sedimentary units include the Cantwell Formation in Alaska (~71°N paleolatitude; Fiorillo et al., Reference Fiorillo, McCarthy and Hasiotis2016) and the Horseshoe Canyon Formation in Alberta (~55°N paleolatitude; calculated from online paleolatitude calculator of van Hinsbergen et al., Reference van Hinsbergen, De Groot, van Schaik, Spakman, Bijl, Sluijs, Langereis and Brinkhuis2015). The inferred paleoclimates under which the Cantwell and Horseshoe Canyon formations were deposited were likely analogous to modern, continental humid climates in the Köppen scheme, marked by strong seasonality due to annual change in photoperiod (Tomsich et al., Reference Tomsich, McCarthy, Fowell and Sunderlin2010; Quinney et al., Reference Quinney, Therrien, Zelenitsky and Eberth2013; Fiorillo et al., Reference Fiorillo, McCarthy and Hasiotis2016). Modern scorpions and tarantulas prefer tropical to lower temperate latitudes (Williams, Reference Williams1987; Lourenço, Reference Lourenço, Gopalakrishnakone, Possani, Schwartz and Rodríguez de la Vega2015; Abbassi and Mustoe, Reference Abbassi and Mustoe2018; Ochoa and Rojas-Runjaic, Reference Ochoa, Rojas-Runjaic, Rull, Vegas-Vilarrúbia, Huber and Señaris2019; Perafán et al., Reference Perafán, Ferretti, Hendrixson and Pérez-Miles2020), at which continental humid climates do not typically occur.

The trackways produced by modern arachnids show major differences from the trackways from the Wapiti Formation. For example, scorpion trackways generally lack the distinct heteropody observed in the Wapiti Formation specimens (Brady, Reference Brady1947; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Minter and Braddy2007; Clendenon and Brand, Reference Clendenon and Brand2023). By contrast, tarantula trackways exhibit heteropody, but their imprints are more circular than the track imprints described here (Brady, Reference Brady1947; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Minter and Braddy2007; Clendenon and Brand, Reference Clendenon and Brand2023). Trackways produced by other Araneae are less well documented, but an Agelenidae (grass spider) trackway reported by Eiseman et al. (Reference Eiseman, Charney and Carlson2010) shows four track imprints per series, one or two of which are highly elongate because of the tarsi dragging across the surface. Such elongation does not occur in the Wapiti Formation trackways. However, the most notable difference is in the depth of the track imprints. The imprints of scorpions and tarantulas are usually shallow, which is especially apparent in substrates with relatively high water content (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Minter and Braddy2007; Clendenon and Brand, Reference Clendenon and Brand2023). The scorpion and tarantula trackways produced during experiments by Clendenon and Brand (Reference Clendenon and Brand2023) are comparable in external width to the trackways reported here (on average 51.9–62.6 mm for scorpions and 59.7–76.5 mm for tarantulas), yet none are as deeply impressed. While unknown Late Cretaceous scorpions and spiders could conceivably have produced trace fossils comparable to those described here, other arthropods should also be considered as potential trackmakers.

Horseshoe crabs (Xiphosura) are aquatic chelicerates sometimes found in non-marine settings (e.g., Mujal et al., Reference Mujal, Belaústegui, Fortuny, Bolet and López2018; Bicknell et al., Reference Bicknell, Kimmig, Budd, Legg, Bader, Haug, Kaiser, Laibl, Tashman and Campione2022; Xing et al., Reference Xing, Wang, Klein and Gao2024; cf. Shibata and Varricchio, Reference Shibata and Varricchio2020), and possible xiphosuran trackways have been reported from the upper Paleocene fluvial deposits of the Paskapoo Formation of southwest Alberta (Micrichnus paleocenus Russell, Reference Russell1940). However, xiphosurans typically produce trackways with opposite symmetry, bifid imprints, and strong heteropody due to the outermost limbs being used as “pushers” to propel the body (Alberti et al., Reference Alberti, Fürsich and Pandey2017; King et al., Reference King, Stimson and Lucas2019). In addition, their trackways are commonly associated with drag mark(s) produced by a single tail and/or single or paired lateral genal spines (Shu et al., Reference Shu, Tong, Tian, Benton, Chu, Yu and Guo2018). Therefore, horseshoe crabs are also unlikely to have produced the trackways described here.

On the basis of the overall shape and size of the fossil arthropod trackways from the Wapiti Formation and the sedimentary context in which they occur, we propose that these trackways were likely produced by crayfish or similar decapods. Crayfish (which refers to the sister taxa Astacoidea and Parastacoidea) are common freshwater decapods found today in temperate zones in North America, as well as South America, Europe, East Asia, Oceania, and Madagascar (Crandall and Buhay, Reference Crandall, Buhay, Balian, Lévêque, Segers and Martens2008; Kawai and Crandall, Reference Kawai, Crandall, Kawai and Cumberlidge2016). It is worth noting that there is a clear biogeographic dichotomy between Astacoidea, which are present only in the Northern Hemisphere (Laurasia), and Parastacoidea, which are limited to the Southern Hemisphere (Gondwana). A few possible decapod body and trace fossils have previously been reported from Cretaceous deposits that formed at high latitudes, namely the Griman Creek Formation (~60°S; Bell et al., Reference Bell, Bicknell and Smith2020) and the Otway and Strzelecki groups in Australia (78 ± 5°S; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Rich, Poore, Schultz, Austin, Kool and Vickers-Rich2008), and the Cantwell Formation in Alaska (71 ± 10°N; Fiorillo et al., Reference Fiorillo, McCarthy and Hasiotis2016). In addition, Tshudy et al. (Reference Tshudy, Donaldson, Collom, Feldmann and Schweitzer2005) reported excellently preserved decapod crustaceans from exposures of the Coniacian Badheart Formation, located ~70 km northwest of the present study area. However, this decapod, which was named Hoploparia albertaensis Tshudy et al., Reference Tshudy, Donaldson, Collom, Feldmann and Schweitzer2005, was marine in habitat and thus does not represent a potential trackmaker for footprints preserved in a continental deposit such as the Wapiti Formation.

The body-fossil record of crayfish extends back to the Triassic (Hasiotis and Mitchell, Reference Hasiotis and Mitchell1993), but an unequivocal crayfish (or related decapod) trace-fossil record extends back to the Permian (Hasiotis et al., Reference Hasiotis, Mitchell and Dubiel1993; Hembree and Swaninger, Reference Hembree and Swaninger2018), with possible earlier burrows from the Late Devonian (Audo et al., Reference Audo, Hasiotis and Kawai2023). A comprehensive molecular study combined with data on fossil lobsters (Achelata, Astacidea, Glypheidea, and Polychelida) suggests the split between the crayfish and lobster lineages may have occurred in the Devonian or Carboniferous to Permian (Bracken-Grissom et al., Reference Bracken-Grissom, Ahyong, Wilkinson, Feldmann and Schweitzer2014). It is thought that Astacoidea were present in North America by the Early Cretaceous (Audo et al., Reference Audo, Hasiotis and Kawai2023).

Fairchild and Hasiotis (Reference Fairchild and Hasiotis2011) and Clendenon and Brand (Reference Clendenon and Brand2023) observed trackways produced by modern crayfish in different environmental settings (underwater and on subaerial surfaces that varied in moisture content, grain size, and degree of inclination). During underwater locomotion, crayfish use the posterior three pairs of pereiopods (walking legs) for walking on the substrate and the anterior walking legs (pereiopods 2) periodically for stability and rarely for walking (Pond, Reference Pond1975; Fairchild and Hasiotis, Reference Fairchild and Hasiotis2011). Instead, the anterior pair of walking legs (pereiopods 2) are chelate and serve a larger role in food exploitation (Holdich and Lowery, Reference Holdich and Lowery1988). The differential significance of the walking legs during aquatic locomotion and the chelate nature of pereiopods 2 and 3 result in heteropody of modern crayfish trackways (Fairchild and Hasiotis, Reference Fairchild and Hasiotis2011; Clendenon and Brand, Reference Clendenon and Brand2023). Division of labor among the four pairs of walking legs is not as pronounced during terrestrial locomotion (Pond, Reference Pond1975), although heteropody is still visible in modern crayfish trackways produced in subaerial walking on damp to saturated substrates (Clendenon and Brand, Reference Clendenon and Brand2023). Heteropody occurs in the Wapiti Formation trackways in that the inner- and outermost imprints are larger and deeper than the others (Figs. 5, 7), further supporting our inference that the trackmaker was crayfish-like. In addition, neoichnological experiments by Clendenon and Brand (Reference Clendenon and Brand2023) showed crayfish track imprints to be deeper than those of scorpions and tarantulas under consistent experimental conditions. Crayfish trackways on subaerially exposed surfaces illustrated in online blog posts also show deep track imprints and are almost identical to the trackways reported herein (Martin, Reference Martin2012; Evans, Reference Evans2016; Fahringer, Reference Fahringer2016). The difference in imprint depth is probably because crayfish are about four times heavier than scorpions and spiders of similar size (scorpions and tarantulas weighing 6–7 g can produce trackways with external widths that overlap with those produced by crayfish weighing ~27 g; Clendenon and Brand, Reference Clendenon and Brand2023).

One major difference between many modern crayfish trackways and those from the Wapiti Formation is the lack of uropod impressions that occur as two parallel grooves medial to the track series. This lack can be explained by either the trackmaker having elevated its telson above the substrate while walking underwater (Fairchild and Hasiotis, Reference Fairchild and Hasiotis2011) or the substrate having been too firm for the uropod to deform (Clendenon and Brand, Reference Clendenon and Brand2023). In overall morphology, the Wapiti trackways are most similar to those produced by modern crayfish on “wet drying” substrates (Clendenon and Brand, Reference Clendenon and Brand2023). It is likely that the narrow, weight-bearing legs deform comparably firm substrates by concentrating pressure at the points of contact, whereas the broad and dragging motion of the uropod distributes a portion of the animal’s weight over a larger area, failing to generate the pressure needed to overcome the cohesion of wet sediment. However, subaerial exposure of the track-bearing surfaces was likely brief judging from the complete lack of desiccation cracks and absence of plant roots. It is also possible that the trackways were produced in a fully subaqueous setting, but modern subaqueous track imprints differ from the Wapiti Formation specimens in lacking sharp margins (e.g., Fairchild and Hasiotis, Reference Fairchild and Hasiotis2011), likely due to infilling of the imprints by surrounding sediment after the legs have been lifted off the substrate.

Despite the progress over the past few decades in the palichnology of crayfish burrows (e.g., Hasiotis and Mitchell, Reference Hasiotis and Mitchell1993; Genise et al., Reference Genise, Bedatou and Melchor2008; Zonneveld et al., Reference Zonneveld, Lavigne, Bartels and Gunnell2006; cf. Genise, Reference Genise2017), only a few arthropod trackways have been attributed to crayfish, often on dubious grounds (Rose et al., Reference Rose, Harris and Milner2021). The first widely accepted fossil crayfish trackway to be described was the type specimen of Siskemia eurypyge Rose et al., Reference Rose, Harris and Milner2021 from a lacustrine shoreline deposit in the Lower Jurassic Moenave Formation of southwest Utah, USA (Rose et al., Reference Rose, Harris and Milner2021). This trackway is similar to those of modern crayfish, consisting of leg imprints that are ovoid to elongate and positioned with staggered symmetry; the Utah trackway also resembles those from the Wapiti Formation in most respects but shows two distinct parallel uropod drag impressions on the inside of the track series, a defining characteristic of Siskemia. Recently, a second possible crayfish trackway was reported from the Lower Cretaceous Wonthaggi Formation of Australia (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Lowery, Hall, Rich, Morton, Kool, Swinkels and Vickers-Rich2021, Reference Martin, Lowery, Hall, Rich and Edwards2024). This trackway was also reported to be Siskemia-like, but a fuller taxonomic appraisal has not yet been published. Another trackway that may be of crayfish origin was referred to Octopodichnus isp. and is from estuarine overbank deposits of the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation in Montana, USA (Shibata and Varricchio, Reference Shibata and Varricchio2020). The Two Medicine trackway predates the Wapiti Formation trackways by ~5 million years (79.603 ± 0.096 Ma; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Swisher and Horner1993) and consists of series of four variably arranged imprints, at least two of which are described as consistently didactyl (Shibata and Varricchio, Reference Shibata and Varricchio2020). No tail drag marks were observed. While Shibata and Varricchio (Reference Shibata and Varricchio2020) did not specify the potential trackmakers, it is possible that the tracks were produced by crayfish or anatomically similar brackish-marine decapods, depending on the degree of marine influence.

Another group of large decapods that inhabited freshwater environments during the Late Cretaceous was crabs (Brachyura). The divergence of freshwater crabs from among their marine ancestors is thought to have occurred in the Early Cretaceous (Tsang et al., Reference Tsang, Schubart, Ahyong, Lai, Au, Chan, Ng and Chu2014; Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Ballou, Luque, Watson-Zink and Ahyong2024). However, the native distribution of modern North American freshwater crabs is limited to Mexico (Yeo et al., Reference Yeo, Ng, Cumberlidge, Magalhães, Daniels, Campos, Balian, Lévêque, Segers and Martens2008; Cumberlidge et al., Reference Cumberlidge, Ng, Yeo, Magalhães and Campos2009). Moreover, the trackways produced by modern crabs are different from the trackways described herein. When crabs walk sideways, which is characteristic of many species, their trackways are typically asymmetrical with irregular patterns of series repetition; and when they walk straight, the imprints are typically comma shaped due to leg dragging (e.g., Melchor et al., Reference Melchor, Genise, Farina, Sánchez, Sarzetti and Visconti2010; examples of marine crabs: Frey et al., Reference Frey, Curran and Pemberton1984; Abbassi and Mustoe, Reference Abbassi and Mustoe2018). Both morphologies are attested in trace fossils interpreted as crab trackways, including Foersterichnus rossensis Pirrie et al., Reference Pirrie, Feldmann and Buatois2004 (for forward walking with elongated leg imprints) and Laterigradus lusitanica de Carvalho et al., Reference de Carvalho, Pereira, Klompmaker, Baucon, Moita, Pereira, Machado, Belo, Carvalho and Mergulhão2016 (for sideways walking). In addition, and except for only a few marine groups, brachyurans lack subchelae on their walking legs (Davie et al., Reference Davie, Guinot, Ng, Castro, Davie, Guinot, Schram and Klein2015) and therefore cannot produce bifid tracks like those observed in the Wapiti Formation trackways.

Other (potential) decapod trace fossils

The precise nature of the trackmaker responsible for the isolated tracks from the Wapiti Formation remains unclear, although it can be reasonably inferred that they also were produced by crayfish or similar arthropods. Judging from the abundance of organic matter in the mudstone slabs, the substrate was littered with dead plant matter that could have produced variations in substrate consistency, affecting the way animal tracks were preserved and accounting for the presence of some isolated marks similar to the imprints in the trackways. An alternative interpretation is that the isolated marks were formed during probing behavior by crayfish as they sought to find and consume food (Holdich and Lowery, Reference Holdich and Lowery1988). Fairchild and Hasiotis (Reference Fairchild and Hasiotis2011) observed that crayfish use legs 2 and 3 (the non-pusher legs), as well as the antennae, to probe the sediment. The two sets of legs used for probing have subchelae, which may explain why some of the isolated tracks are bifid (Fig. 9.1).

The antennae of a crayfish can be used to probe into the sediment, and Fairchild and Hasiotis (Reference Fairchild and Hasiotis2011) also observed antennal sweeping motions that left marks on the sediment surface. Such antennal sweep marks can be observed in some of the supplementary images in Clendenon (Reference Clendenon2023). Three surficial marks on UALVP 62351, which superficially resemble Helminthoidichnites Fitch, Reference Fitch1850 (cf. Buatois et al., Reference Buatois, Mángano, Maples and Lanier1998, Reference Buatois, Wetzel and Mángano2020; Metz, Reference Metz2020), may be sweep marks from the antennae of the trackway maker. Although Fairchild and Hasiotis (Reference Fairchild and Hasiotis2011) described the antennal sweep marks as resembling Undichna Anderson, Reference Anderson1976 and Batrachichnus Woodworth, Reference Woodworth1900, they might be expected to vary in morphology depending on tracemaker behavior. Two of the surficial marks from the Wapiti Formation occur parallel to the trackway (just outside of the track series) and seem likely to have been generated by the trackway producer (Fig. 6). The third trace is “kinked” and can be interpreted as having been formed when the tracemaker moved its right antenna laterally from the trackway midline then took a step forward. Alternatively, the surficial marks could be trails left by arthropod larvae or other vermiform grazers (e.g., Buatois et al., Reference Buatois, Mángano, Maples and Lanier1998, Reference Buatois, Wetzel and Mángano2020; Lima et al., Reference Lima, Minter and Netto2017; Metz, Reference Metz2020).

Conclusions

A trackway from the Upper Cretaceous Wapiti Formation has been identified as Octopodichnus cf. O. raymondi. Judging from the trackway’s morphology and inferred paleoenvironmental context, a crayfish or similar decapod crustacean is the most likely trackmaker. While tracks assigned to Octopodichnus are generally attributed to arachnids (e.g., Brady, Reference Brady1947; Lockley et al., Reference Lockley, Culver, Wegweiser, Lucas, Spielmann and Lockley2007; Good and Ekdale, Reference Good and Ekdale2014), the swampy paleoenvironment and the high-latitude setting of the Wapiti Formation, as well as differences in imprint morphologies between the Wapiti trackways and those of arachnids, make such an attribution inapplicable in this case. Freshwater crabs are also dismissed as plausible trackmakers due to the absence of fossil freshwater crabs in the Cretaceous of western North America and morphological differences between the Wapiti Formation trackways and those produced by modern and fossil crabs (cf. Frey et al., Reference Frey, Curran and Pemberton1984; Melchor et al., Reference Melchor, Genise, Farina, Sánchez, Sarzetti and Visconti2010; Abbassi and Mustoe, Reference Abbassi and Mustoe2018). To date, this is only the third well-substantiated example of a possible crayfish (or similar arthropod) fossil trackway to be reported. Therefore, these occurrences add to our knowledge of the understudied invertebrate diversity from the Wapiti Formation and to the generally sparse Late Cretaceous fossil record of crayfish worldwide (Audo et al., Reference Audo, Hasiotis and Kawai2023).

The trackways from the Wapiti Formation provide a good example of how different arthropod taxa can produce similar trace fossils and illustrate the need to revise Octopodichnus and related ichnogenera (such as Stiaria and Paleohelcura) as the ichnotaxobases are still not entirely clear. In addition, the unique mode of preservation (buried under a volcanic ash layer) and high fidelity of the arthropod trackways and other minute ichnites highlights the potential for further important discoveries in the Wapiti Formation.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by NSERC Discovery Grants to M.K.G., J.-P.Z. and C.S. and an endowment associated with the Philip J. Currie Professorship at the University of Alberta. The field study was conducted under Province of Alberta Permit to Excavate Palaeontological Resources 24-049. We extend our gratitude to T. Nielsen, who piloted his jet boat to access the outcrop and retrieve the specimens described in this paper. We also thank C. Clendenon, J. Evans, and T. Martin for helpful discussions on crayfish trackways. G. Mángano, N. Minter, and an anonymous reviewer helped us improve our manuscript. Finally, we thank all the BADP field crew members who kept us company and assisted us during fieldwork and Northwestern Polytechnic for generously accommodating most of the crew during the field period.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.