Introduction

As the urgency to mitigate the most severe impacts of climate change intensifies, experts stress the need for effective and timely policies (Ripple, Wolf, Gregg et al. Reference Ripple, Wolf, Gregg, Rockström, Mann, Oreskes, Lenton, Rahmstorf, Newsome, Xu and Svenning2024). While studies have shown that people overwhelmingly support stronger governmental climate action, there is often a misperception – both among policymakers and the public – that such support lacks majority backing, complicating efforts to advance specific climate measures (Bouman, Steg and Dietz Reference Bouman, Steg and Dietz2024). This study empirically tests two possible hurdles to the effective implementation of climate policies. One key question is whether political elites are more or less supportive of specific measures to reduce emissions compared to voters. Additionally, it is crucial to understand the political elites’ second-order beliefs: their perceptions of and expectations about what citizens want. According to Mildenberger and Tingley (Reference Mildenberger and Tingley2019), misconceptions about public opinion regarding climate policy preferences among both elected and unelected elites have led to weak political incentives for ambitious climate policy reforms. They call for a closer examination of second-order beliefs as a crucial factor influencing climate policy inaction.

Citizens’ second-order beliefs are important because such beliefs influence support for climate policies. A recent study finds that correcting widespread misperceptions about the prevalence of climate-friendly behaviors and norms significantly increases individuals’ willingness to act against climate change and their support for related policies, particularly among skeptics (Andre, Boneva, Chopra et al. Reference Andre, Boneva, Chopra and Falk2024b). A growing research field explores politicians’ perceptions of public opinion, addressing a significant gap in the study of political behavior. Politicians are found to hold a relatively pessimistic view of voters’ capabilities – differing from the more optimistic and policy-oriented views held by citizens about their own capabilities (Lucas, Sheffer, Loewen et al. Reference Lucas, Sheffer, Loewen, Walgrave, Soontjens, Amsalem, Bailer, Brack, Breunig, Bundi and Coufal2024). Unelected elites’ interpretations of public preferences matter because these elites often frame the policy options available to elected officials, shape public debate, and play central roles in policy enforcement. Their second-order beliefs have also been found to be inaccurate (Furnas and LaPira Reference Furnas and LaPira2024).

Understanding how elites, both elected and unelected, perceive public opinion is crucial, as their potential misperceptions can have democratically consequential effects, influencing whether policies reflect the public will. This research note adds insights from a European context in the domain of policies aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions. For the first time, the first- and second-order climate policy beliefs of citizens, elected elites, and unelected elites are integrated in one study. We make use of a coordinated survey of three groups that hold central roles in the process of policy-making: a population-based survey sample of ordinary citizens (N = 1,739), a sample of locally elected politicians (N = 794), and a sample of unelected elites; bureaucrats employed in the central administration (N = 1,192). We consider the latter two groups as functional elites in that they, through their positions, shape policy and the public discourse. That said, the two elite groups differ in a crucial sense: politicians represent their voters and depend on re-election to belong to the elite, whereas bureaucrats belong to the elite by virtue of their occupation.

We find that elected elites are much less likely to support the measure aimed at reducing emissions compared to citizens. Furthermore, we find that all groups underestimate the level of support among citizens for a meat-free day. A key contribution of our study is the significant difference in second-order beliefs that we find between citizens and elites. While we have seen indications that both citizens and political elites tend to underestimate public support for climate policies, our study is the first to directly compare groups of citizens, elected elites, and unelected elites. What stands out is a striking pattern when comparing the elites to citizens through a nested four-step OLS regression: both elected and unelected elites are significantly more likely than citizens to assume that public support is in the minority when we control for sociodemographic, ideological, and partisan factors. We argue that such underestimations are consequential because they influence political discourse as well as policy development, potentially leading to stagnation of climate policy processes.

First-order beliefs about climate politics

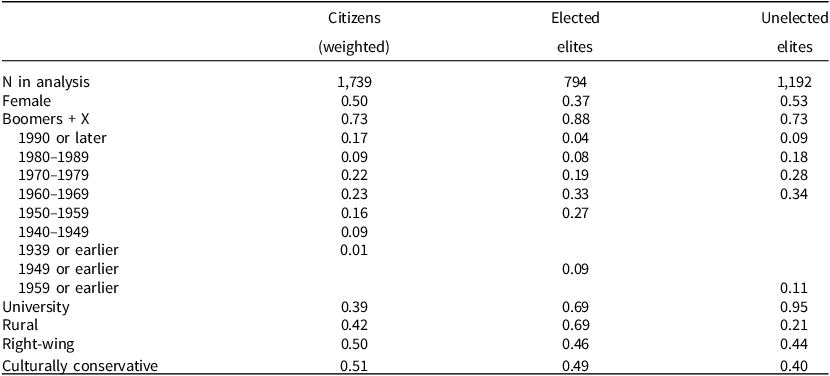

By first-order beliefs, we simply refer to respondents’ own opinions, be they citizens or elites. Research on the determinants of citizens’ climate preferences suggests that demographic variables only marginally predict attitudes when contrasted with policy-specific beliefs, climate change evaluations, and psychological factors (Bergquist, Nilsson, Harring et al. Reference Bergquist, Nilsson, Harring and Jagers2022). It is worth noting, though, that the demographic characteristics vary among the three groups examined in this note. As shown in Table 1, women and younger generations are underrepresented among elected elites. Education is the variable where the groups differentiate the most: around 40 percent of citizens have a university degree, while 60 percent of elected elites and 95 percent of unelected elites do so. Another crucial difference between the samples is how the elected elites (local politicians) are mostly rural, while the unelected elites (central bureaucrats) are mostly urban. The average local politician is more rural than the average citizen as each urban representative represents far more voters than a rural representative. Consequently, while these demographic predictors may be relatively weak in predicting support for climate policies, their influence still warrants consideration in this study. They play a key role in shaping our expectations for the findings and are essential to our modeling of both first- and second-order beliefs.

Table 1. Summary of relevant characteristics of each group

Notes: Mean values on the variables included in the regression analysis by panel. Female, ‘Boomers + X’ (share born in 1979 or earlier) and university are dichotomous variables. Rural, right-wing, and culturally conservative range from 0 to 1.

Party competition in Europe is mainly structured along two dimensions. We consider both the traditional left–right dimension and the social liberalism–conservatism dimension (Ford and Jennings Reference Ford and Jennings2020) in our analysis. Most scholarship on political cleavages focuses on party competition, but a recent analysis demonstrates that both these dimensions are important also for voters and that the second dimension has gained strength since the turn of the millennium (Dassonneville, Hooghe and Marks Reference Dassonneville, Hooghe and Marks2024). Most political behavior research subsumes support for climate policy issues into the liberal end of this liberalism–conservatism dimension, but some argue that environmentalism should be considered an independent dimension of political preferences (Kenny and Langsæther Reference Kenny and Langsæther2023). We adopt the broader social liberalism–conservatism framework to guide our expectations about various groups’ attitudes toward policies aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Accordingly, our analysis draws not only on studies specifically examining attitudes toward climate policies but also on the wider body of literature exploring attitudes along the social liberalism–conservatism axis.

Women and the younger generation are expected to be more in favor of a meat-free day because they support climate policies to a larger extent generally (Helliesen Reference Helliesen2023). Also, more specifically related to meat reduction, these groups are more aware of and willing to reduce their meat consumption for environmental concerns (Sanchez-Sabate and Sabaté Reference Sanchez-Sabate and Sabaté2019). More highly educated citizens are expected to be more likely to support a meat-free day, as higher education is associated with more culturally liberal values (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Stubager Reference Stubager2008). Culturally conservative values are generally more widespread in rural areas, while culturally liberal values are dominant in urban areas (Luca, Terrero-Davila, Stein et al. Reference Luca, Terrero-Davila, Stein and Lee2023). A center-periphery cleavage on attitudes toward climate policies has been identified across regions in Western Europe (Arndt, Halikiopoulou and Vrakopoulos Reference Arndt, Halikiopoulou and Vrakopoulos2023). The specific policy focus in this study presents a case of a climate policy with a potentially clear urban–rural divide, as rural respondents tend to oppose meat reduction as a measure to mitigate climate change more than urban respondents (Boer and Aiking Reference Boer and Aiking2022; Falck Reference Falck2023).

Studies of elites’ personal climate policy preferences are limited. In Norway, elected representatives are found to be strikingly congruent with citizens on various climate policy issues (Helliesen Reference Helliesen2023). A study from Finland finds that policymakers are more worried about climate change and more willing to pay to mitigate it compared to the public (Rapeli and Koskimaa Reference Rapeli and Koskimaa2022). A study from Flanders finds the opposite: that citizens are overall somewhat more favorable of climate policies than politicians are (Walgrave and Soontjens Reference Walgrave and Soontjens2025).

Given the sociodemographic composition of the panels, expectations for the first-order beliefs of elected elites are mixed. On the one hand, elected elites typically have higher education levels, a key factor in predicting progressive attitudes toward climate policy. On the other hand, younger generations and women – groups more likely to support a meat-free day – are underrepresented in politics (Helliesen Reference Helliesen2023). Additionally, locally elected representatives often reside in less central areas compared to the average citizen, which is associated with holding more conservative attitudes. Thus, we have no clear expectation of the direction elected elites will lean vis-a-vis citizens on the question of a meat-free day. In contrast, the unelected elites in this study are exclusively recruited from the central administration and therefore reside in more urban areas. They all possess higher education levels. Consequently, we expect that unelected elites are more likely than citizens to support implementing a weekly meat-free day in canteens.

Second-order beliefs about climate politics

Climate change presents a collective problem, with measures to reduce emissions often entailing individual costs. Globally, most people are inclined to combat climate change and expect their national governments to do the same (Andre, Boneva, Chopra et al. Reference Andre, Boneva, Chopra and Falk2024a). However, multiple studies have shown that citizens tend to underestimate other people’s belief in climate change and support for climate policies (Abeles et al. Reference Abeles, Howe, Krosnick and MacInnis2019; Andre, Boneva, Chopra et al. Reference Andre, Boneva, Chopra and Falk2024a; Ballew et al. Reference Ballew, Rosenthal, Goldberg, Gustafson, Kotcher, Maibach and Leiserowitz2020; Leviston, Walker and Morwinski Reference Leviston, Walker and Morwinski2013; Sokoloski, Markowitz and Bidwell Reference Sokoloski, Markowitz and Bidwell2018; Sparkman, Geiger and Weber Reference Sparkman, Geiger and Weber2022). Based on previous research, we anticipate that citizens will underestimate popular support for implementing a meat-free day in Norway. Such underestimations can be consequential, as studies have shown that perceptions of others’ beliefs, attitudes, and willingness to bear costs related to climate change mitigation can significantly influence one’s own attitudes and willingness to act (Abeles et al. Reference Abeles, Howe, Krosnick and MacInnis2019; Geiger and Swim Reference Geiger and Swim2016; Wyss, Berger and Knoch Reference Wyss, Berger and Knoch2023).

According to the diamond of representation (Miller and Stokes Reference Miller and Stokes1963), voters can be well represented either by electing politicians that hold similar views as them or if their representatives know what their constituency wants. The first mechanism of representation – overlapping views of elected politicians and their voters – is often referred to as congruence. The second mechanism emphasizes that the quality of representation in a liberal representative democracy depends on elected elites having a reasonable idea of the interests and values of the public. Previous research shows that perceptions of public opinion significantly influence elite action (Butler, Nickerson, et al. Reference Butler and Nickerson2011; Miller and Stokes Reference Miller and Stokes1963; Walgrave, Soontjens and Sevenans Reference Walgrave, Soontjens and Sevenans2022; Walgrave, Soroka, Loewen et al. Reference Walgrave, Soroka, Loewen, Sheafer and Soontjens2024). Several studies find that elected elites tend to overestimate their constituents’ support for conservative positions. This conservative bias is found both across policy domains and across the political spectrum and is connected to the fact that politicians tend to be exposed to voter groups that are more conservative (Broockman and Skovron Reference Broockman and Skovron2018; Pereira Reference Pereira2021; Pilet, Sheffer, Helfer et al. Reference Pilet, Sheffer, Helfer, Varone, Vliegenthart and Walgrave2024; Walgrave, Jansen, Sevenans et al. Reference Walgrave, Jansen, Sevenans, Soontjens, Pilet, Brack, Varone, Helfer, Vliegenthart, Van Der Meer and Breunig2023; Walgrave, Soontjens and Sevenans Reference Walgrave, Soontjens and Sevenans2022). In a recent study of German citizens and politicians, Kübler (Reference Kübler2024) challenges this dominant finding by not identifying a general conservative bias, yet politicians’ second-order beliefs are skewed to the right when it comes to climate protection also in her analysis. Thus, based on previous research, we expect Norwegian politicians to underestimate public support for a meat-free day in canteens.

A just transition into sustainable societies depends not only on elected political elites. Unelected political elites’ second-order beliefs can also shape policy implementation. Bureaucratic elites perform crucial democratic roles as they formulate and implement policies (Bersch and Fukuyama Reference Bersch and Fukuyama2023). Yet, their position vis-à-vis citizens is radically different. As bureaucrats cannot be electorally sanctioned for their attitudes, they can use their knowledge and experience to argue for what they consider to be in the public interest without being strategic. And although the objectivity criterion is vital among bureaucrats, their job being to craft and implement policies that have been politically decided upon, their own views and their perceptions of what voters want can also influence politicians’ decision-making (Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger and Stokes Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Mildenberger and Stokes2019). Although unelected elites do not have a direct electoral connection to public opinion, our sample of bureaucrats are nevertheless constrained by public and stakeholder opinions in their professional life. This, combined with higher education levels and professional specialization, should make our bureaucrat sample better at estimating public opinion than ordinary citizens (Furnas and LaPira Reference Furnas and LaPira2024). That said, we have not seen much evidence of unelected elites actually having more accurate second-order beliefs. Instead, the available evidence points to unelected elites also having inaccurate perceptions of public opinion, and that these second-order beliefs are inferred from their own policy preferences (Furnas and LaPira Reference Furnas and LaPira2024; Mildenberger and Tingley Reference Mildenberger and Tingley2019). Given the composition of the sample, and what we know about the central role of projection effects in second-order beliefs, our expectations for the unelected elites’ second-order beliefs are mixed. On the one hand, they might overestimate support for meat-free days among citizens because they are more likely to be in favor of it themselves. On the other hand, we expect them to be more accurate in reading public opinion by virtue of their professional background and experience.

Research design

The data were collected through the coordinated online panels for research on democracy and governance in Norway (KODEM). This included the Norwegian Citizen Panel (Ivarsflaten et al. Reference Ivarsflaten, Dahlberg, Storelv, Løvseth, Bjånesøy, Bye, Böhm, Fimreite, Gregersen, Knudsen, Nordø, Schakel and Tvinnereim2023a), the Panel of Elected Representatives (Ivarsflaten et al. Reference Ivarsflaten, Bach, Fimreite, Finseraas, Stein, Løvseth, Storelv and Vestre2023b), and the Panel of Public Administrators (Ivarsflaten et al. Reference Ivarsflaten, Bach, Fimreite, Finseraas, Stein, Løvseth, Storelv, Vestre and Løseth2023c). Detailed information about the panels is provided in the online Supplementary Material (SM) and the methodology reports (Skjervheim et al. Reference Skjervheim, Grendal, Bjørnebekk and Wettergreen2023, Skjervheim et al. Reference Skjervheim, Bjørnebekk, Wettergreen and Grendal2023a, and Skjervheim et al., Reference Skjervheim, Bjørnebekk, Wettergreen and Grendal2023b).

This study sees citizens, elected elites, and unelected elites as strategic actors. For strategic political actors, being right means understanding what matters to the public. They are not focused on exact numbers like ‘52 percent of people support having a meat-free day in canteens’. Instead, they care about knowing if a majority supports it. The most common approach in literature on second-order beliefs is to ask respondents to estimate the share of the public support. These estimates are then compared to citizens’ actual responses to the same questions in a survey conducted in parallel. This way of measuring perceptual accuracy gives great analytical leverage and precision in measurements. We do however question the variability in such estimates. Following from the idea of both citizens and elites as strategic actors, a much simpler task is given in this study. Second-order beliefs are measured with a simple binary response scale. Respondents could choose between stating that they believed a majority or a minority of people in Norway supported the survey item.Footnote 1 This study then cannot detect minor mistakes in public opinion readings but is instead geared toward capturing mistakes that potentially carry political consequences.

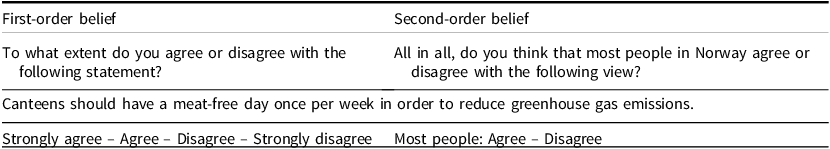

Research on citizens, elected elites, and unelected elites suggests projection as an explanation for biased second-order beliefs: people tend to think that others agree with them (see Mullen, Atkins, Champion et al. (Reference Mullen, Atkins, Champion, Edwards, Hardy, Story and Vanderklok1985) for a meta-analysis of the false consensus effect, Esaiasson and Holmberg (Reference Esaiasson and Holmberg1996) and Sevenans, Walgrave, Jansen et al. (Reference Sevenans, Walgrave, Jansen, Soontjens, Bailer, Brack, Breunig, Helfer, Loewen, Pilet and Sheffer2023) for accounts of projection among politicians, and Furnas and LaPira (Reference Furnas and LaPira2024) on unelected elite misperception of public opinion). Because we know that people’s second-order beliefs are influenced by their first-order beliefs, we risk reinforcing this effect by obtaining biased measurements in our analysis if we ask each individual to answer both questions. By employing a between-subject design, this risk is mitigated. The exact same, simple 1 × 2 design was fielded in each of the three samples. Table 2 presents the question wording. Randomization is not only useful to identify causal mechanisms. In this study, computer-assisted randomization is taken advantage of to measure second-order beliefs against first-order beliefs, collected in the same survey, but not by asking the same respondents. By design, this study cannot report within-subject results analyzing the relationship between first- and second-order beliefs. Instead, we adopt a collective representation approach as opposed to dyadic representation (Andeweg Reference Andeweg2011) and analyze elites’ beliefs in the aggregate.Footnote 2 Despite dependent variables with no midpoint option, the main analyses report linear regression models for easier interpretation.Footnote 3 The regressions are run with robust standard errors clustered by panel (Blair, Cooper, Coppock et al. Reference Blair, Cooper, Coppock, Humphreys and Sonnet2022). Operationalization details are included in the SM.

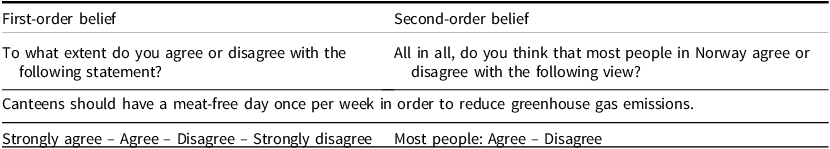

Table 2. Question wording: 1x2 survey design

The case of meat-free days

To study how citizens and elites evaluate the general opinion toward climate policy, we study a specific measure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions: The issue of a meat-free day once a week in canteens with the purpose being to reduce greenhouse gas emissions clearly stated in the survey question. This is a measure particularly relevant to the local political level, because it is typically municipal politicians who are responsible for handling questions about meat-free days in public canteens. This is something that has been debated by politicians in Norway. We discuss this further in the SM.

This specific policy is particularly interesting for at least three different reasons. First, the potential for emission cuts through meat reduction is large. On a global scale, food systems cause 35 percent of environmental pollution originating in human activity. Notable reductions in the consumption of animal-based foods in high-income societies are important for sustainable development (Jarmul, Dangour, Green et al. Reference Jarmul, Dangour, Green, Liew, Haines and Scheelbeek2020; Parlasca and Qaim Reference Parlasca and Qaim2022; Xu, Sharma, Shu et al. Reference Xu, Sharma, Shu, Lin, Ciais, Tubiello, Smith, Campbell and Jain2021). Unlike carbon dioxide, methane has a relatively short atmospheric lifespan, making reductions effective in the short term. Significantly cutting methane emissions can help slow the rate of near-term global warming, and in many European countries, reducing livestock has the greatest mitigation potential (Shindell, Sadavarte, Aben et al. Reference Shindell, Sadavarte, Aben, Bredariol, Dreyfus, Höglund-Isaksson, Poulter, Saunois, Schmidt, Szopa and Rentz2024).

Second, from earlier investigations, we know that citizens are quite split in their views on this issue: 55 percent agree that we should eat less meat to reduce emissions (see SM Figure A3). This makes the selected question an interesting item to investigate, whether various actors tend to overestimate or underestimate the support. A systematic review of research on consumer attitudes finds that meat reduction is among the least preferred of personal options to counter climate change in a variety of contexts (Sanchez-Sabate and Sabaté Reference Sanchez-Sabate and Sabaté2019). European citizens, in particular, do not view a decrease in meat consumption as a crucial factor for sustainability (Boer and Aiking Reference Boer and Aiking2023). Boer and Aiking (Reference Boer and Aiking2023) posit that the general public lacks an understanding of the critical role that reducing meat consumption plays in meeting ambitious climate-related objectives.

Third, attitudes toward meat reduction to reduce carbon emissions serve as a good starting point for investigating perceptions of popular climate policy support in Europe more generally. We do not have any reasons to believe that this is a climate policy where Norwegians are different from other European citizens. The average total meat supply per person is similar across borders in Europe (Our World in Data 2021), meat is traditionally and culturally important to European citizens, and the agribusinesses are facing similar challenges across borders. When comparing personal climate actions among EU citizens, it is evident that meat reduction efforts are not currently as prevalent as mainstream sustainability actions (Boer and Aiking Reference Boer and Aiking2023).Footnote 4 Data from the Norwegian Citizen Panel and Panel of Elected Representatives show that meat reduction is the least popular of the climate policies studied (Helliesen Reference Helliesen2023).

Although comparative evidence is lacking, we do not see any reasons to believe that adapting this measure to reduce emissions will be easier or harder in Norway compared to other European countries.Footnote 5 Although only reporting results on one specific issue, this study is about gauging the public sentiment on measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions more generally. There is always a trade-off in (survey) research between fielding items that are close to theoretical concepts – often more general statements – and items that are closer to respondents’ minds. The latter outweighed the former consideration in this study. When designing the survey, we aimed at choosing a policy that would maximize generalizability by choosing an issue that would not be very context-specific to Norway. Topics related to energyFootnote 6 and transportationFootnote 7 – which are the areas with the largest potential for cutting emissions – would be hard to generalize to a broader European context. Resources only allowed fielding of one single item. Although some context-specific matters do of course impair the generalizability of the results,Footnote 8 the concern addressed by this study is not context-specific. However, it has been demonstrated that perceptual accuracy varies widely from issue to issue (Pereira Reference Pereira2021: 1312–1313). To establish a more comprehensive understanding of the underestimation of support for climate measures, additional evidence from diverse issues and varying contexts is essential.

Results

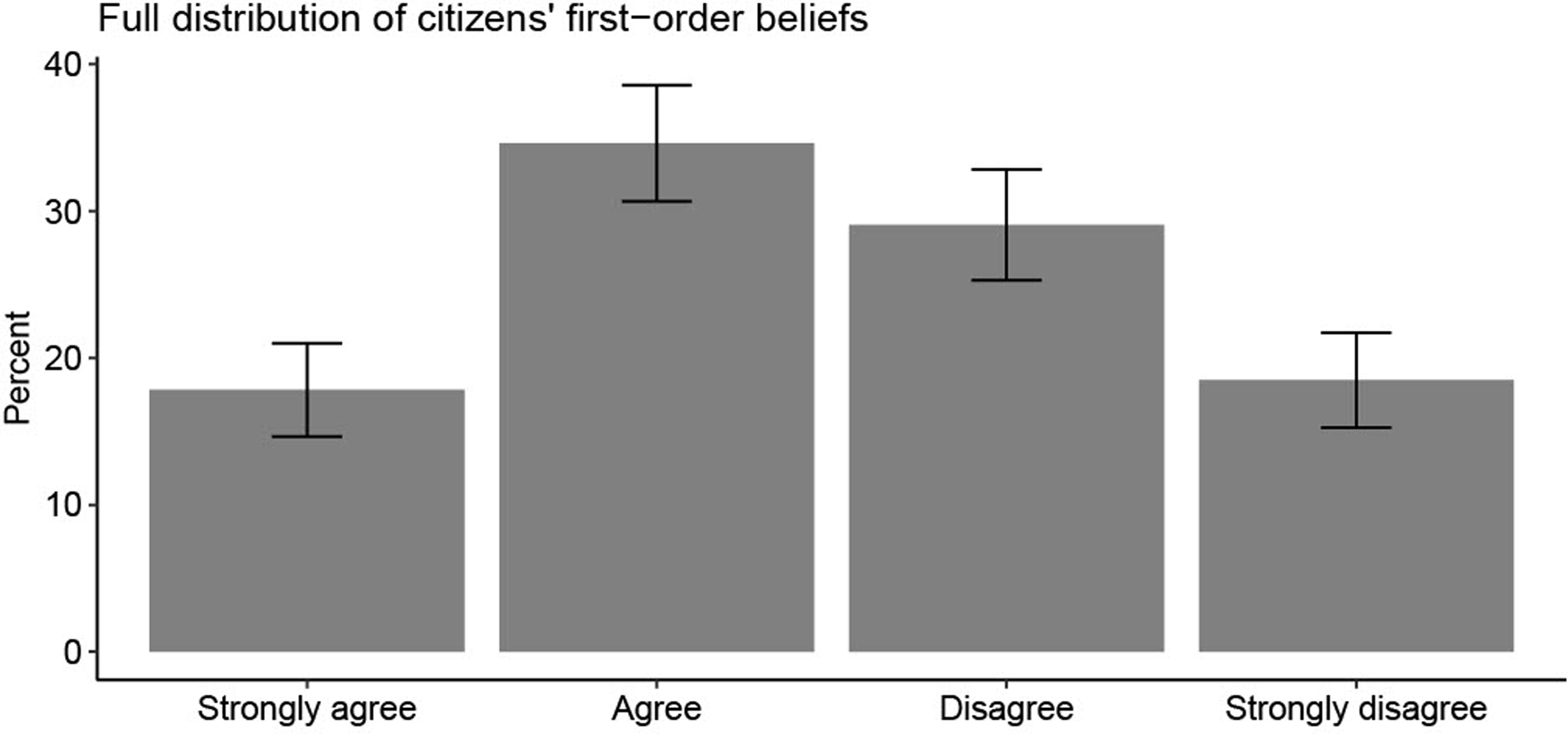

To assess the first-order beliefs of elites relative to citizens and to assess the second-order beliefs of citizens and elites, we rely on public opinion data. Figure 1 shows that Norwegians are split in their support for meat-free days to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Specifically, the survey item in this study regarding meat-free days in canteens reveals a 52 percent support rate when those responding ‘Strongly agree’ (17.8%) and ‘Agree’ (34.6%) are taken together. This estimate is based on data collected alongside the elite study.Footnote 9

Figure 1. Attitudes toward canteens having a meat-free day once per week in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions among Norwegian citizens.

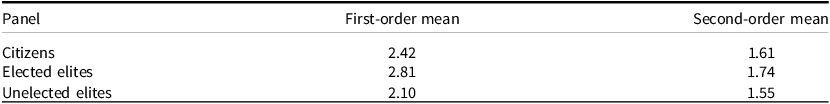

Table 3 presents the mean values for each dependent variable by group. The mean weighted value for citizens’ first-order beliefs is 2.42, indicating a position between ‘Agree’ and ‘Disagree’, slightly leaning toward ‘Agree’. For elected elites, the mean value is 2.81, suggesting a tendency toward ‘Disagree’. Unelected elites have a mean value of 2.10, showing a lean toward ‘Agree’.

Table 3. Mean values of first- and second-order beliefs by panel

Notes: First-order values: Strongly agree (1) – Agree (2) – Disagree (3) – Strongly disagree (4). Second-order values: Agree (1) – Disagree (2). Survey weights included for citizens.

Regarding second-order beliefs, citizens have a weighted mean value of 1.61, indicating a perception that the majority of Norwegians disagree. Elected elites have a mean value of 1.74, reflecting a stronger belief that the majority disagreeFootnote 10 . Unelected elites have a mean value of 1.55, also suggesting that they tend to believe the majority disagree, but to a lesser extent than citizens.

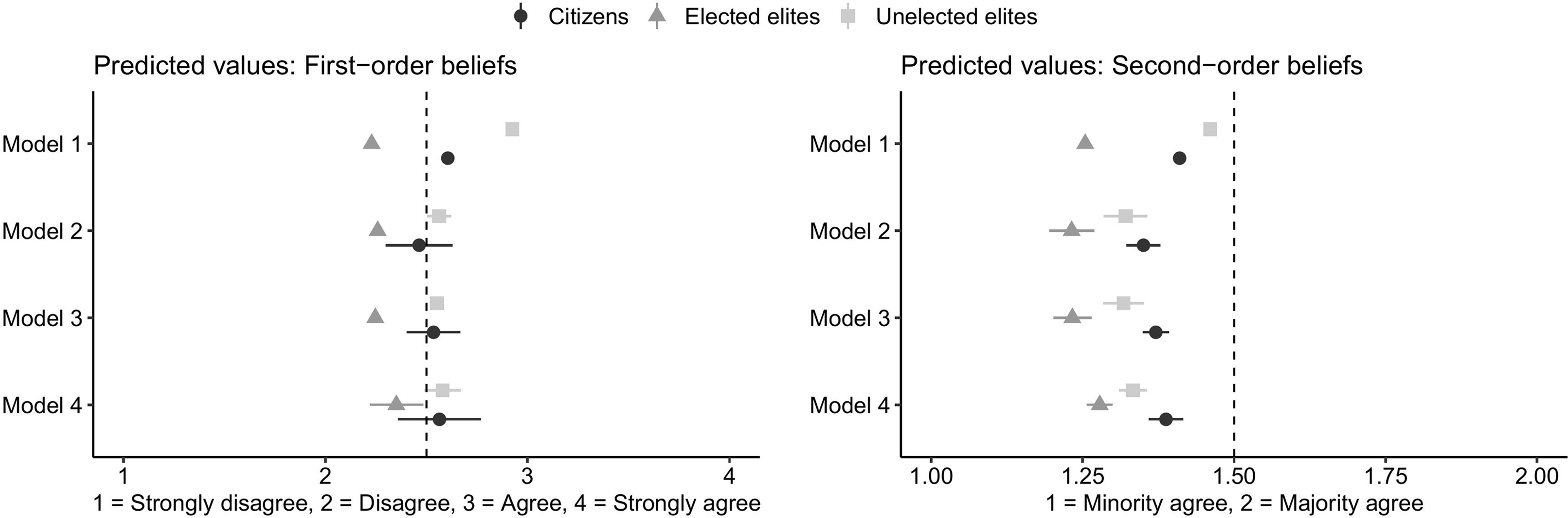

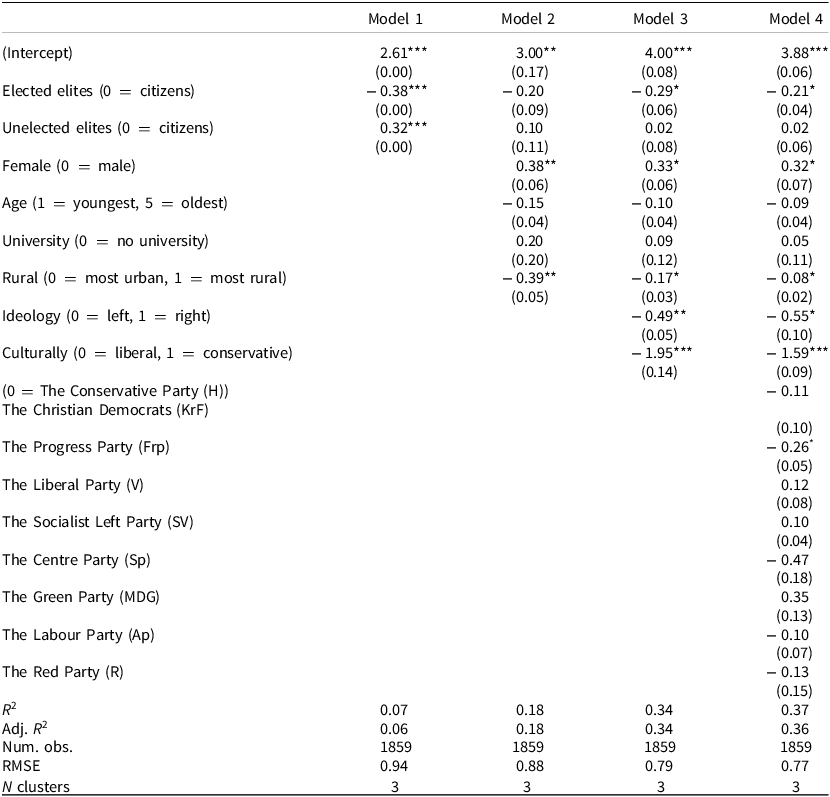

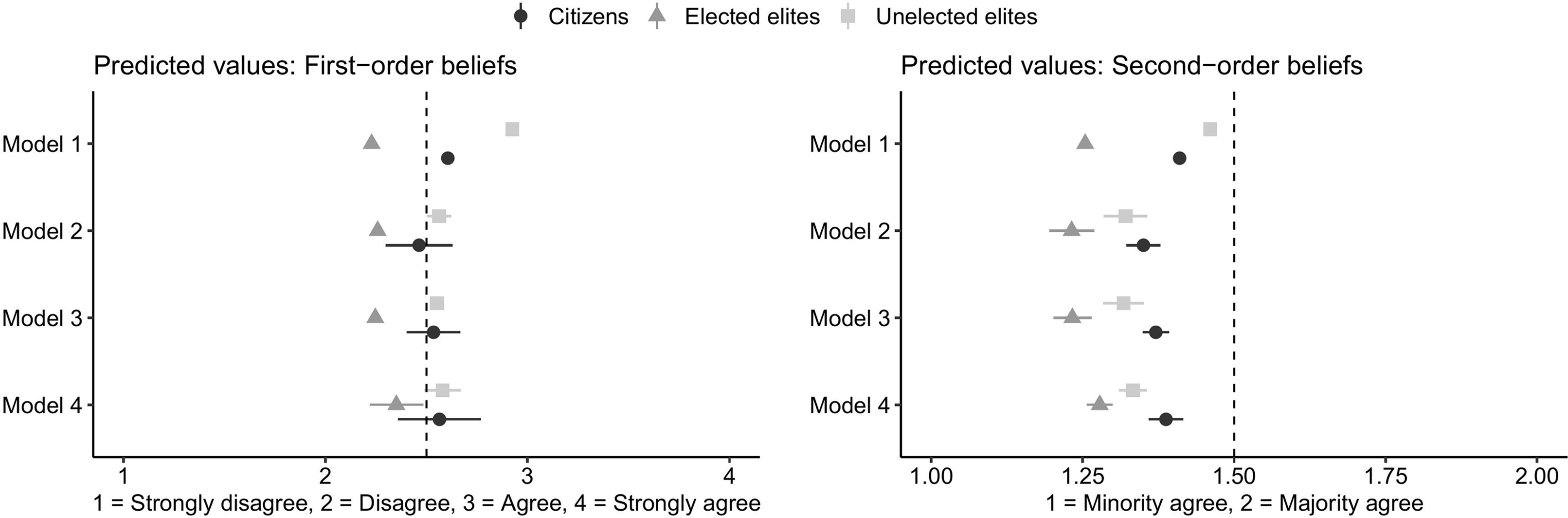

The main findings are illustrated in Figure 2. For this analysis, all three samples are pooled and a variable indicating which panel they belong to has been added to the dataset. Table 4 presents the detailed results from four nested regression models of first-order beliefs. Table 5 reports the results from similar nested models but with second-order beliefs as the dependent variable.

Figure 2. First-order and second-order beliefs among citizens, elected elites, and unelected elites.

Table 4. OLS regression of first-order beliefs on meat-free days in canteens. Dependent variable coded: Strongly disagree (1) – Disagree (2) – Agree (3) – Strongly agree (4)

***P < 0.01; **P < 0.05; *P < 0.1.

Table 5. OLS regression of second-order beliefs on meat-free days in canteens. Dependent variable coded: Most disagree (1) – Most agree (2)

***P < 0.01; **P < 0.05; *P < 0.1.

Model 1 for first-order beliefs reflects the baseline finding described in Table 3. The population is split regarding whether canteens should have a meat-free day once a week: the estimate is between ‘disagree’ and ‘agree’, leaning slightly toward ‘agree’. Elected elites’ first-order beliefs in model 1 lean closer to ‘disagree’, while unelected elites are near ‘agree’. The difference between citizens and both elite groups vanishes in model 2 with the inclusion of sociodemographic variables. Model 3 adds two measures of ideology: self-placement on the left–right axis and an index indicating cultural conservatism. With these ideological measures included, elected elites significantly differ from citizens, being less likely to support meat-free days. Model 4 includes political party affiliation. Importantly, including the party variable does not eliminate the statistically significant difference between elected elites and citizens observed in models 1 and 3. Elected elites tend to oppose meat-free days more than citizens, even after considering political party affiliation. Unelected elites’ own opinions are not different from citizens’ when we take indicators of political attitudes into account.

The next analysis explores whether citizens, elected elites, and unelected elites tend to underestimate or overestimate public support for this issue among Norwegians. Second-order belief results show that across all three groups, respondents are more likely to believe a minority supports a meat-free day once a week. All point estimates are to the left of 1.50 in Figure 2 (the stippled line). This indicates a perceived resistance to the idea of a weekly meat-free day in canteens among the majority of each group. Model 1 shows that elected elites are significantly less likely to believe that most Norwegians support a meat-free day in canteens compared to citizens, and unelected elites are significantly more likely than citizens to think a majority support it. Elected elites remain significantly less likely to think a majority supports a meat-free day once a week, even after accounting for sociodemographic variables in model 2. Interestingly, the coefficient shifts to negative values for unelected elites in this model, indicating that when we account for sociodemographic factors, the unelected elites go from being more likely than citizens to think that a majority would support a meat-free day to being more likely than citizens to think that a minority would support a meat-free day. Model 3 adds ideological variables. Elected elites still significantly underestimate majority support compared to citizens when accounting for sociodemographic and ideological factors. The negative coefficient for unelected elites suggests that they are more likely to underestimate support compared to citizens, and this underestimation is statistically significant. Model 4 includes the party variable. Adding the party variable does not explain the significant difference between elected elites and citizens observed in models 1–3. Elected elites continue to be significantly more likely to underestimate support for meat-free days compared to citizens. The observed difference also remains significantly lower for the unelected elites compared to citizens.

The descriptive means confirm the expectations we had for first-order beliefs based on the broader literature on attitudes along the social liberalism–conservatism dimension and the sociodemographic composition of the groups: elected elites are less in favor of a meat-free day and unelected elites are more in favor, compared to ordinary citizens. Model 2 confirmed that the differences between the groups are mainly explained by the sociodemographic composition of the panels, as no significant differences were observed between the groups when this was included in the regression model. Particularly women and urban respondents are more likely to be in favor of a meat-free day. We have also shown in models 3 and 4 that political beliefs and orientations are influential in predicting first-order beliefs. Individuals with right-wing ideology, those who hold more culturally conservative values, and those affiliated with the Progress Party (Frp) are less likely to support a meat-free day.

The second-order belief results suggest that all groups are more likely to underestimate than overestimate public support for climate policies, and that this underestimation is significantly more pronounced among elites than among citizens. The descriptive means suggest that elected elites’ tendency to think there is minority support among citizens is extensive, and that such perceptions are less pronounced among citizens and unelected elites. However, through rigorous and robust regression analyses, we have shown that both elite groups tend to underestimate support more than citizens when sociodemographic, ideological, and party indicators are accounted for in nested OLS models. This indicates that individuals holding elite positions in Norway receive some kind of different signal, or process information in a different way, than ordinary citizens. This is in line with the disconnect between public opinion and political decision-making that has been found elsewhere in the domain of climate politics, where widespread support for more climate action is often misinterpreted as opposition (Bouman, Steg, and Dietz Reference Bouman, Steg and Dietz2024). Support for the specific survey item investigated in this study is not widespread, but it is staggering how substantial the differences in the various groups’ second-order beliefs are. It can also be worth noting for future analyses in this domain that men and older respondents are more likely to underestimate support for a meat-free day compared to their counterparts. Those affiliated with the Progress Party (FrP) are also more likely to underestimate support compared to voters of the Conservative Party (H). This is all in line with the projection hypothesis.

Discussion

The key contribution of this study lies in its unique data collection approach, which simultaneously targets three democratically significant and typically difficult-to-reach populations: a representative sample of ordinary citizens, locally elected political representatives, and centrally employed public administrators. By directly comparing these three groups, we highlight a significant and underexplored difference in second-order beliefs: elected and unelected elites are substantially more likely than citizens to underestimate public support for climate policies. This misalignment in perceptions is particularly serious given the influential roles elites play in shaping policy and public discourse. The specific survey item we addressed was carefully chosen for its familiarity to respondents across all three samples. At the same time, it represents a central policy issue in the climate mitigation debate. By focusing on this issue, our study provides valuable insights into the dynamics of second-order beliefs in the context of climate change mitigation policy. We think the dynamics observed in Norway could potentially be generalized to similar contexts in this region.

While we have argued for the broader relevance of data derived from a single survey item in a single country, it is clear that more empirical evidence is needed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the second-order beliefs among these various groups. Walgrave and Soontjens (Reference Walgrave and Soontjens2025) make a significant contribution in this regard by examining six different climate issues where they conclude – along the same lines as we do – that locally elected politicians underestimate public support for climate policies. They argue that there are two possible approaches to implementing climate policies: politicians can either be responsive to citizens’ demand for such policies or act responsibly by implementing them despite a lack of voter demand, based on a belief that it is the right thing to do given the severe consequences of climate change. These two independent studies of local politicians in Flanders and Norway suggest that local politicians are neither responsive nor responsible when it comes to climate change mitigation.

This research note does not explore the mechanisms behind the underestimation of support for climate policies. Investigating this more rigorously will be an important next step. It could be that climate politics, often unpopular, present politicians with a dilemma. Those seeking re-election may perceive the risk of electoral loss as outweighing potential gains, prompting them to align with opposition to climate policies rather than endorse new, radical initiatives. At the same time, our results suggest that this tendency to underestimate support for climate policies is also present among political elites that are not seeking re-election. Exploring differences in second-order beliefs between elected and unelected elites is a particularly promising research avenue for understanding the mechanisms behind perceptual accuracy. The second-order beliefs presented in this study may be a significant barrier to the implementation of effective climate policies. Bouman, Steg and Dietz (Reference Bouman, Steg and Dietz2024) suggest that such perceptions are compounded by the influence of vocal minority groups, economic elites, and media narratives that exaggerate resistance to climate policies. Further research is essential to delve into dynamics and identify strategies to overcome current barriers to responsive or responsible policy-making on climate mitigation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676525100467.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, IF, upon request. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality restrictions, as they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants, particularly elite respondents.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the constructive comments received from the editor and anonymous reviewers at EJPR. Earlier versions of this manuscript were presented at the following venues, where we benefited from valuable feedback: the Centre for Climate and Energy Transformation (CET), the Digital Social Science Core Facility (DIGSSCORE), Living with Climate Changes (2023), EPSA 2023, SWEPSA 2023, the Norwegian National Political Science Conference 2024, NOPSA 2024, and ECPR 2024. We owe special thanks to Elisabeth Ivarsflaten, Stefaan Walgrave, and Dustin Tingley for their crucial feedback.

Funding statement

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (The Inclusive Politics Project, grant no. 101001133).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.