Introduction

The tiger Panthera tigris has declined across its range and now occurs in only 13 countries. Poaching is a major cause of this decline, driven by the demand for tiger parts (Nowell, Reference Nowell2000). We focus on the problem of tiger poaching in the Bangladesh Sundarbans, which was considered to be a stronghold for the species, with an estimated population of 300–500 individuals in 2009 (Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Greenwood, Barlow, Islam, Hossain and Khan2009) but where there are now estimated to be only 106 remaining (Dey et al., Reference Dey, Kabir, Islam, Chowdhury, Hassan and Jhala2015).

For centuries social elites have killed tigers for sport in the Indian subcontinent (Rangarajan, Reference Rangarajan2001). Local hunters, known as shikaris, were employed as guides and trackers to support these hunts (Chakraborthy, Reference Chakraborthy2010). Described as low-caste individuals, who were looked down upon by other community members (Rangarajan, Reference Rangarajan2001; Chakraborthy, Reference Chakraborthy2010), shikaris assumed a stronger identity in the days of the British Raj, establishing a strong social bond with the British hunters (Sramek, Reference Sramek2006), not unlike the relationship observed on Scottish sporting estates between the gentleman sportsman and his local highland ghillie (MacMillan & Leitch, Reference MacMillan and Leitch2008; MacMillan & Phillip, Reference MacMillan and Phillip2010). During the British period shikaris were also hired to kill tigers in the Sundarbans because of the high number of human fatalities caused by tigers (Rangarajan, Reference Rangarajan2001; Chakraborthy, Reference Chakraborthy2010).

Poaching has been identified as a high-priority threat to the species in the region (Aziz et al., Reference Aziz, Barlow, Greenwood and Islam2013) but although studies have explored tiger-killing behaviour in villages, human–tiger conflict and the link between local usage of tiger parts and tiger killing (Khan, Reference Khan2009; Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Ahmad and Smith2013; Inskip et al., Reference Inskip, Ridout, Fahad, Tully, Barlow and Barlow2013, Reference Inskip, Fahad, Tully, Roberts and MacMillan2014; Saif et al., Reference Saif, Russell, Nodie, Inskip, Lahann and Barlow2016), there has been no research on the range of people involved, their motives and methods, and their links to the commercial trade. Our aim is to establish who is killing tigers, why and how, with a view to designing more effective conservation interventions that complement existing law-enforcement efforts. This type of study is rare in the literature on tiger conservation but provides essential baseline information upon which an effective and sustainable tiger conservation strategy can be implemented.

Study area

The Sundarbans is an extensive mangrove forest spanning the border between Bangladesh and India. In Bangladesh it covers an area of 6,017 km2 (Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Greenwood, Barlow, Islam, Hossain and Khan2009) and is divided into four administrative ranges (Satkhira, Khulna, Chandpai and Sarankhola), which are surrounded by eight subdistricts, known as upazilas (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 The locations of 29 Village Tiger Response Teams and surrounding subdistricts (upazilas) in the Bangladesh Sundarbans.

Methods

Sampling strategy and interview approach

We conducted semi-structured interviews with local people in the four administrative ranges during December 2011–June 2013 to gather information about tiger killing. We also conducted informal interviews with a researcher, two journalists, a police officer and a lawyer. Questions were mostly open-ended, giving respondents the opportunity to discuss everything they felt was relevant, and interviews continued until the data became saturated (Newing et al., Reference Newing, Eagle, Puri and Watson2011). This approach has been used in other studies seeking an in-depth understanding of wildlife killing (Pratt et al., Reference Pratt, Macmillan and Gordon2004; MacMillan & Han, Reference MacMillan and Han2011). Ethical approval was obtained from the Zoological Society of London and the University of Kent.

In deciding our research strategy we considered several factors. Firstly, we considered it unrealistic to expect interviewees to answer truthfully any directly incriminating questions about illegal wildlife killing for profit (Solomon et al., Reference Solomon, Jacobson, Wald and Gavin2007). Secondly, we were cognizant of the need to overcome any reservations they may have had about being questioned about a sensitive subject by an urban, well-educated female Bangladeshi. We invested time (1–7 days) in building trust with each respondent through social activities, teaching their children and participating in their daily activities. We were confident that trust had been established when many interviewees showed us tiger parts they had obtained.

To verify sensitive data, similar questions were asked in different ways during different phases of the interview. The reliability of information obtained was assessed by asking for details about timing and location; for example, whether an event took place before or after cyclone Sidr (November 2007) or Aila (May 2009), which government was in power or which grade their son or daughter was in at the time. To persuade tiger killers to take part in the interview we agreed that participants could describe tiger killing events in the third person, without admitting their involvement in the process. They were also assured before the interview that the source of their knowledge or experience of killing would not be requested.

We did not request or record interviewees’ names or addresses, and anonymity was assured. All interviews were carried out in Bengali by SS to maintain consistency and trust. As some respondents felt uncomfortable about providing personal information (e.g. their religion), we omitted non-essential personal questions. To avoid any false or misleading answers we did not provide direct financial incentives to the interviewees (Gavin et al., Reference Gavin, Solomon and Blank2010). Interviews were generally 2–4 hours in duration. Interviewees were offered snacks during the interview; the interviews that lasted > 2 hours included breaks, and lunch or dinner was offered as a traditional gesture.

We used purposive sampling, actively seeking members of the village community with various levels and forms of engagement with tiger killing, categorized as (1) members of a Village Tiger Response Team, (2) general members of the community, and (3) tiger killers. Village Tiger Response Team members are unpaid volunteers from the community who help prevent tigers being killed if they enter a village. Established by the conservation NGO WildTeam, response teams are located in areas where human–tiger conflict is prevalent (Fig. 1). Team members are trained and experienced in dealing with such conflict; they are also knowledgeable about village life and forest resource collection practices.

Initially we conducted meetings with the members of each team and explained the research and ethical issues involved. We identified the most appropriate team members for subsequent, more in-depth interviews (n = 46) based on their knowledge and experience of wildlife poaching, killing of tigers in villages, and pirate activity. We interviewed 1–3 members of each team, on average. The interview guide (Supplementary Material 1) focused on their motivations for joining a Village Tiger Response Team, their role when a stray tiger enters a village, and their understanding of the uses and values of tiger parts and tiger poaching.

General members of the community (n = 62) were selected based on their knowledge and experience of tiger parts, wildlife poaching, killing of tigers in villages, and pirate activities. Interviewees were recruited using snowball sampling (Newing et al., Reference Newing, Eagle, Puri and Watson2011) following initial introductions by Village Tiger Response Team members in the community. Interviewees included honey collectors, wood cutters, fishers, labourers, shopkeepers, jewellery makers, gunin (people who recite spiritual scripts to ward off tigers), kobiraj (local doctors), tailors, businessmen, carpenters and victims of tiger attacks. The interview guide (Supplementary Material 2) focused on their attitudes and behaviours regarding tigers entering villages, tiger killing, dead tigers, local and commercial trade of tiger parts, and poaching.

Interviewees categorized as tiger killers were those who had killed a tiger in the forest. The interview guide used for general members of the community was also used for this group but, when the opportunity arose, the interviewer probed for more sensitive details about tiger killing activity. The tiger killers were selected using snowball sampling through various local contacts and police records. Some general members of the community mentioned that they had been involved in tiger killing incidents in the forest, and were subsequently recategorized as tiger killers. In total, we conducted 33 interviews with tiger killers, of which five were poachers, 27 were opportunistic killers (i.e. shikaris) and one had killed in self-defence.

In total, we conducted 141 interviews in 54 villages (39 of which bordered the Bangladesh Sundarbans). Using the main livelihood of the respondents as an indicator, respondents were identified as forest-going people (n = 67), non-forest-going people (n = 54) or others (n = 20), comprising people who had stopped going to the forest for safety reasons (n = 10) or because of old age (n = 6), and four forest department staff.

Data analysis

Data on poaching, killing, trade and other related issues were coded and thematic models were developed to identify links between various components (Pratt et al., Reference Pratt, Macmillan and Gordon2004). Comparing the models and identifying the words used most often by the various groups (e.g. shikari, pirates, poison, guns, recent demand, trader) facilitated the identification of emergent themes and issues. We used the Institutional Analysis and Development framework for the structural presentation of the data (Ostrom et al., Reference Ostrom, Gardner and Walker1994). This is a robust framework for describing the components of a system and establishing interactive links among them. In this analysis people engaged in killing, transporting and trading tigers are the components, and trade for commercial and cultural reasons and social relationships are the interactive links. We tested the rigour and accuracy of our descriptions and interpretations by analysing the data several times, triangulating data from various interviewees, and examining them to find common patterns (Newing et al., Reference Newing, Eagle, Puri and Watson2011). We used the qualitative data analysis software NVivo 10 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) for data management and to ensure all data were included in the analysis.

Results

We identified five groups involved in tiger killing: village tiger killers (i.e. local people who kill tigers that have entered their village), poachers, shikaris, trappers and pirates (Table 1).

Table 1 Information about the methods and motives of various tiger Panthera tigris killing groups in the Bangladesh Sundarbans (Fig. 1),and related conservation interventions and research needs, presented using the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework.

Village tiger killers

When a tiger enters a village thousands of people gather, armed with axes, sticks, bamboo rods and billhooks, to kill the tiger. Despite efforts by the Forest Department and members of the Village Tiger Response Team to restrain the crowd, tigers are often killed if they attack someone or do not return to the forest before sunset. As one interviewee (34; Supplementary Table S3) mentioned, ‘the Forest Department wants to save the tiger but they cannot even go close to it as the public will hit them too.’

Local people typically act in a group for safety reasons but also to avoid punishment for killing the tiger. Motivations for participation vary from excitement to retribution. Interviewees reported that local people kill tigers because they fear for their lives or their livestock, but also in revenge for previous tiger attacks. People who risk death to confront a tiger are highly regarded in the community and this may also act as a motive. As one interviewee (85; Supplementary Table S3) reported, ‘everyone who is brave hits the tiger.’ A man who was killed by a tiger in 2011 after he had pulled its tail is revered locally for his courage. Others mentioned that they participated in tiger killing to collect parts for traditional medicine or to sell: ‘A man asked me to collect a canine for him and he will give me BDT 2,000 (USD 26). So I went with an axe to kill it [the tiger].’ Regardless of their motive for killing, local people collect almost all parts of a dead tiger, including teeth, skin, bones and whiskers, for the local and commercial trade.

Poachers

Forty-three interviewees reported that poachers kill tigers and sell tiger parts. Of these, five admitted their direct involvement in tiger poaching activities in two ranges (Sarankhola and Satkhira) and provided a detailed description of poachers’ activities. In groups of 4–6, typically disguised as fishers to avoid attention, they set snare traps in the forest to catch deer or wild boar. The carcasses are then laced with poison (e.g. Furadan, n = 11; Basudin, n = 2; or Ripcord, n = 2) and placed on known tiger trails.

After killing a tiger, poachers remove the skin in one piece from head to tail, including the claws and whiskers. They bury body parts in a safe location, which they monitor until the meat decomposes and the right opportunity to sell arises. Tiger poaching is the main livelihood of the poachers. Using a trusted commercial network of buyers many have been killing tigers and selling their skins for 20 years or more. To optimize their profit they may liaise with several buyers, depending on the part being offered for sale.

When a tiger dies…we take the skin off, throw away the internal organs and take the rest. We sell the dry meat and bones to one buyer and the skin to another. (131; Supplementary Table S3)

Interviews indicated that the number of covert poaching incidents is rising. Although we could not quantify this trend, interviewees related it to recent reports about non-local Bangladeshi traders from larger cities offering ‘big’ money (USD 65 per kg for bones). One poacher (whose group had killed 27 tigers during 2010–2012) stated that tigers were becoming increasingly scarce and poachers now had to roam wider afield to meet demand.

Members of poaching gangs are relatives or friends but tensions over money and other issues can lead to frequent turnover of a gang's membership.

I used to kill tigers with my uncle and cousins. They poisoned a tiger…sold the parts but didn't inform me. Later I was informed about that deal from the buyer. I felt insulted and stopped working with them. (123; Supplementary Table S3)

Women are not involved in poaching but help in the village; for example by burying bones in the house yard.

Shikaris

All hunting is illegal in the Bangladesh Sundarbans but shikaris kill game covertly, primarily for personal consumption or to treat guests on special occasions. They are respected within the community. Shikaris who do not possess their own guns borrow guns in return for meat or, on occasion, tiger parts. Gun owners lend weapons only to individuals whom they trust not to divulge their identity. In one reported case a shikari injured by a tiger insisted his associate returned the gun to its owner before seeking help from the village.

Shikaris typically go to the forest in small groups. To keep the noise level low, only two or three enter the forest and the others wait in the boat. In the forest they climb a tree bearing new leaves or seasonal fruit, or if they see animal tracks nearby. Facing against the wind they make noises and play with leaves, mimicking rhesus monkeys Macaca mulatta to attract deer (deer consume the leaves dropped by monkeys). They also mimic deer mating calls, known locally as kui, to attract deer. Some shikaris (n = 7) reported hunting at night, using torchlight to locate animals by the reflection from their eyes. Shikaris recite religious verses while loading their guns, to make the meat halal.

All 27 shikaris interviewed admitted killing a tiger at least once in their lifetime. They remove the skin and bury the body in the forest, digging out the bones later. If the tiger does not die nearby the shikaris usually do not try to track it, for their safety. Interviewees (n = 13) have reported seeing dead tigers with bullet holes in the forest.

The shikaris’ motives for tiger killing are complex, driven by various socio-economic factors, such as safety, excitement, retaliation and money (Table 2). The narrative accounts of the shikaris and other interviewees suggest that they kill tigers opportunistically, as they generally go to the forest to kill deer. However, shikaris may not always know a trustworthy dealer and will often accept low prices for tiger parts because of the risks involved. Sometimes after killing a tiger shikaris take only the canines and claws, which can be traded easily in the local community, and leave the skin because it is too risky to sell. Three shikaris reported being coerced into giving skins to commercial traders for free, under threat that they would be reported to the authorities.

Table 2 Statements of some shikaris (with ID codes in square brackets; Supplementary Table S3) regarding their motives for killing tigers in the forest in the Bangladesh Sundarbans (Fig. 1).

Although it was not possible to estimate from our data the total number of tigers killed by shikaris annually, our evidence suggests that they are responsible for a significant number of tiger kills and, like poachers, are finding it harder to kill tigers because the tiger population is dwindling:

In the 90s I used to take the skin from 5–10 tigers each year…after 2000…only 4–5. (88; Supplementary Table S3)

Trappers

Interviewees reported that many local people go to the forest to set traps for deer. Trappers differ from shikaris in terms of killing method, motive and social status. They kill deer predominantly for sale or consumption. They do not have guns, and typically use various types of traps made of rope, including a row of loops, known as fashi faad, in which deer become entangled. Some interviewees (n = 21) reported that a tiger can release itself from these traps unless the loop is stuck around its neck. Another trap, known as chitka, pulls the animal into the air. It can trap a tiger if the rope is strong enough or if iron chain is used instead of rope.

Although the use of iron chain suggests trappers may target tigers occasionally, our findings indicate that killing of tigers by trappers is largely accidental. Many trappers who find a dead tiger will eschew the opportunity to take its parts because they lack a trustworthy network and may face significant difficulties and risks in selling the parts. According to one trapper (26; Supplementary Table S3), ‘we knew about the demand…we were scared…we didn't take the skin.’ Another (96; Supplementary Table S3) described how they found a dead tiger hanging from a sundari tree and became scared and ‘moved to another place.’

Pirates

The main business of the pirates is extortion and kidnapping. Typically, fishers are required to give a certain amount of money to the local pirate gang each season, depending on how many boats, trawlers or fishers they have in their team. After paying the money the fishers get a receipt from the pirates as proof of payment, which they need to show if they encounter the pirates again during the same fishing season. Some local fishers have also been taken hostage or kidnapped to extort money. According to the interviewees, pirates are present throughout the forest and each group has its own range. They try to hide their location to protect themselves from the authorities. A woman (37; Supplementary Table S3) who stumbled into their hideout while collecting wood stated, ‘they held me up for the whole day…took BDT 300 (USD 4) but gave me rice and salt to eat. At midnight they moved out from there and released me so that I could not reveal their new location to anyone.’

Interviewees reported that most pirates are members of the village community and come to the village covertly to meet their families. Some pirate leaders give money to build mosques, and local people respect them. There were no reports of pirates ever having kidnapped any tourists, NGO workers or researchers.

Interviewees (n = 71) reported that pirates killed tigers in the forest for safety and money. A former pirate said that when pirates go to a new place they look for pugmarks as an indicator of tiger presence nearby. If they find pugmarks they try to track the tiger and shoot it. Eleven interviewees mentioned seeing tiger parts being processed for trade while imprisoned by pirates; e.g.:

I was kidnapped three times…in 2007, 2008 and 2010. Last time they took me in their trawler… .A tiger limb hung out from a sack…with skin and claw…a very big sack. The pirate told me, ‘see we killed a tiger, so how long will it take to kill you! (15; Supplementary Table S3)

Around 2008–2009 I have seen two skins in the trawler of X gang.…They told me both the skins are of female tigers. (119; Supplementary Table S3)

They were tanning a skin by hanging it from a rope. (136; Supplementary Table S3)

Although collecting ransom is the main business of the pirates, many interviewees reported that pirates allege that they also kill tigers to protect village residents.

It is not known how many tigers are killed by pirates but it may be a significant number. In 2009 a pirate leader told a researcher that his group had recently killed two tigers within 15 days. Another pirate associate reported that his gang killed two tigers within 5 months in 2013. One interviewee mentioned seeing 12 tiger skins when he was kidnapped 6–7 months previously.

Discussion

There are 76 villages bordering the Bangladesh Sundarbans, which are home to c. 350,000 people. Most of the local people are dependent on the natural resources of the forest for their livelihood, collecting honey, wood, fish, nipa Nypa fruticans leaf and thatching grass (Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Greenwood, Barlow, Islam, Hossain and Khan2009). Conflict between tigers and people is inevitable and some of the highest recorded levels of human mortality from tiger attacks occur in the Bangladesh Sundarbans, with an estimated 20–50 people killed annually whilst extracting resources from the forest (Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Greenwood, Barlow, Islam, Hossain and Khan2009; Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Ahmad and Smith2013). Prior to the formation of the Village Tiger Response Teams a significant number of tigers were also killed annually. During 2008–2012 a total of eight tigers were killed in the villages (WildTeam, unpubl. data). We have established that tiger killing is carried out to protect people and livestock but is also motivated by the desire to obtain tiger parts for local use or pecuniary rewards from the international trade, and by excitement and bravado.

There is no legal basis for tiger killing. Following independence in 1971 the Bangladesh Wildlife (Preservation) (Amendment) Act, 1974 banned tiger killing in Bangladesh for the first time. The Forest Act, 1927 banned the carrying of guns into the forest. Enforcement of these laws is largely the responsibility of the Forest Department, which is the custodian of the forest and its wildlife. The Rapid Action Battalion and Bangladesh Police conduct searches for pirates and other criminals in the forest. In 2010 the national government introduced compensation of BDT 100,000 (USD 1,282) for the families of victims of tiger attacks.

We have established that tiger killing occurs both in the village and in the forest. In the village there is a mutually agreed norm that tiger killing is carried out by the group to avoid individuals being punished (Inskip et al., Reference Inskip, Ridout, Fahad, Tully, Barlow and Barlow2013). In the forest, tiger killers do not follow any specific rules, as their motives vary and most of them kill tigers opportunistically (Saif & MacMillan, Reference Saif, MacMillan, Potter, Nurse and Hall2016).

Community members’ relationship with tigers is broadly aligned with an open access regime, where there is no regulative authority for establishing mutually agreed and enforceable rules and norms. Hence, tiger killing involves the dilemma of the tragedy of the commons (Hardin, Reference Hardin1968), in which every individual acts for their own personal benefit without taking responsibility for conserving resources. In contrast, hunter and gatherer communities of northern Canada, for example, have developed their own institutional structure for the systematic exploitation of wildlife (Padilla & Kofinas, Reference Padilla and Kofinas2014).

People kill tigers in the village and may also belong to pirate or poaching gangs in the forest. The groups that operate in the forest act independently of each other but are connected through a shared trade network for selling tiger body parts; for example, there is some evidence that pirate gangs collaborate with poachers in dealing with international trade networks (A.S.M. Rejuan, pers. comm.). Pirate gangs may also kidnap people who have specific skills in trapping or processing tiger parts.

The various groups involved in tiger killing also interact with law enforcement staff (i.e. Rapid Action Battalion, police, Forest Department) and members of Village Tiger Response Teams. The Village Tiger Response Teams and the Forest Department try to stop people from killing tigers in villages but arrests are mostly restricted to poachers and trappers who are using poison and snare traps.

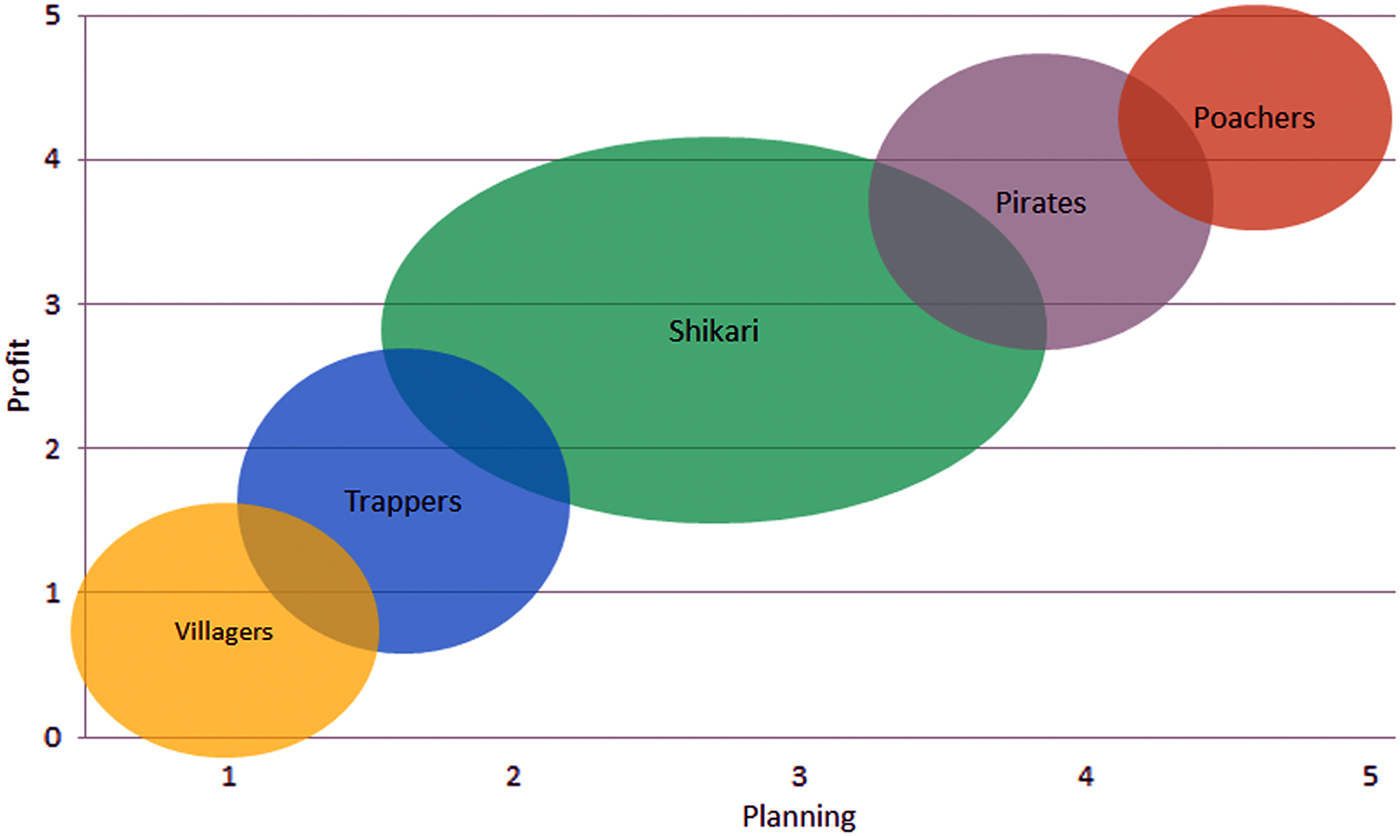

Fig. 2 depicts the behaviour of the various groups involved in tiger killing activities in terms of the main distinguishing characteristics (profit and planning). The degree of overlap suggests the extent of any collaboration in the killing and trade; for example, poachers plan their operations meticulously and kill tigers only for profit, and evidence suggests they often sell parts in collaboration with pirates. Shikaris also kill tigers but occupy a more central position as they have more diverse motives. Trappers occupy a slightly lower position than the shikaris, as their tiger killing is more opportunistic and they have less access to commercial networks.

Fig. 2 Groups of tiger killers in the Bangladesh Sundarbans (Fig. 1) positioned in terms of planning and profit, scored 0–5. The central, larger area occupied by the shikaris reflects their diverse motivations and situations in relation to tiger killing.

Conservation challenges and possible interventions

In the Bangladesh Sundarbans the existence of tiger killers with many and diverse motives creates challenges for tiger conservation. We suggest that tougher enforcement efforts alone will not succeed in reducing tiger killing and that a more dynamic and multifaceted strategy that addresses the various motives and opportunities for tiger killing is required to meet the global goal of doubling the wild tiger population by 2022 (GTRP, 2011).

In 2012 the new Wildlife (Preservation & Protection) Act of Bangladesh introduced tougher punishments for tiger killing (7 years imprisonment); however, this law is not sufficient to combat poaching without effective enforcement measures (Pratt et al., Reference Pratt, Macmillan and Gordon2004). The lucrative nature of the tiger trade means that poachers and their clients can hire experienced lawyers to help them evade punishment, and there are numerous examples of poachers being acquitted during the legal process and avoiding punishment (Saif et al., Reference Saif, Russell, Nodie, Inskip, Lahann and Barlow2016). To combat this situation we suggest that conservation NGOs could hire specialist prosecuting lawyers to act against poachers, an approach that has been used successfully elsewhere (e.g. the Congo; PALF, 2014). Several respondents cited the lack of a trustworthy crime reporting system as a barrier to reporting poaching-related activity. A telephone hotline maintaining the anonymity of the informer could be introduced to assist patrolling operations by the Forest Department.

During 2010–2015 there was an increase in the number of tiger skins and skeletons seized in Bangladesh. Most of the skins lacked bullet marks or other external wounds, suggesting that the tigers were poisoned (Saif et al., Reference Saif, Russell, Nodie, Inskip, Lahann and Barlow2016). Poisoning is the trademark of professional poaching gangs. Banning Furadan and other poisons used to kill tigers might not stop poaching but it would increase costs and reduce activity at least in the short term (Aziz, Reference Aziz2015). Given that the tiger population in the Bangladesh Sundarbans is declining rapidly, any measure that slows the rate of poaching will contribute positively to conservation efforts.

We do not believe that relocation of people would reduce poaching significantly in the Bangladesh Sundarbans, although it has been suggested as a means of conserving tigers and is reportedly favoured by communities such as the Gujjars of north-east India (Harihar et al., Reference Harihar, Veríssimo and MacMillan2015). This option is currently being explored by the development organization Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit and the Bangladesh government and would involve the voluntary relocation of people from villages to reduce pressure on the forest, with training and guidance regarding alternative livelihood options. Although this could help to improve tiger habitat, it is unlikely that commercial poachers would stop poaching, which is lucrative, in favour of an alternative livelihood.

In many countries the authorities shoot poachers on sight (Messer, Reference Messer2010) and in Bangladesh 41 pirates were shot dead by law enforcement authorities in a single year (Dhaka Tribune, 2015). In our view killing people violates the principle of proportionality, and we recommend a less hostile approach (e.g. offering an amnesty and an alternative livelihood to non-commercial tiger-killers) in exchange for assisting the Forest Department with tiger conservation and anti-poaching efforts; Daily Sun, 2016).

We argue that law enforcement alone may not be the best approach to curtail tiger killing by shikaris. An important priority should be to enlist greater support for tiger conservation amongst the population (e.g. by providing access to medical facilities to reduce dependence on traditional tiger medicines; Saif et al., Reference Saif, Russell, Nodie, Inskip, Lahann and Barlow2016). Hunting and trapping activities by the local community can also be tackled through a range of positive incentives. Shikaris do not hunt solely for money or food but also for pleasure and excitement, and although they operate illegally they do so with the support of the community. The guns they use are mostly licensed, and issued on the basis of personal security. One potential solution would be to provide an amnesty whereby guns are handed over in exchange for a reward or a replacement pistol (which are unlikely to be used to kill tigers). Other incentives for compensating shikaris could include the provision of educational or medical facilities to their families, or social activities involving national heroes, such as cricketers.

Providing alternative livelihood options for trappers would reduce their dependency on trapping as a source of income. Training to add value to dairy products is a potential option to explore, as most trappers also possess cows, buffaloes and goats. A similar initiative has been successful in the Ecuadorian Amazon, where local hunters have diversified into chocolate production (Halle & Puyol, Reference Halle and Puyol2014). In the Indian Sundarbans an algaculture project established by a civil organization has significantly changed the lifestyle of local people (Ghosh, Reference Ghosh2015). There is scope for the development of similar projects in Bangladesh.

The formation of Village Tiger Response Teams in 2009 appears to have reduced the number of tigers killed in villages (there have been no such incidents since 2013). However, these teams do not have the capacity to deal with targeted killing of tigers in the forest. Their scope is limited by their lack of institutional authority (Rejuan, Reference Rejuan2014) and their voluntary basis. One option could be to support their activities by providing mediation and negotiation services to help people claim compensation from the Forest Department, as happens in India's Corbett Tiger Reserve; however, the involvement of NGOs can be problematic as the level of support they can offer depends on external funding and the political environment (Rastogi et al., Reference Rastogi, Hickey, Badola and Hussain2014).

This is the first in-depth study of the various tiger killing groups in the Bangladesh Sundarbans. The scenario is complex as it involves multiple groups with different motives, and this complexity is a challenge to tiger conservation and shows the need for a multifaceted approach. We have shared our recommendations from this study with the WildTeam, INTERPOL and TRAFFIC to inform anti-poaching efforts, and also with tiger scientists to update the Bangladesh Tiger Action Plan and the National Tiger Recovery Programme.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Zoological Society of London, Environmental Education and Conservation Global, the Rufford Foundation, and Future of Nature for funding. We also thank Professor Md Anwarul Islam, Dr Adam Barlow, Christina Barlow, Dr Petra Lahann and all colleagues from WildTeam, the research team—Maruf, Nodie, Ratul, Kader and Badshah—and the Village Tiger Response Teams and interviewees for their time and support.

Author contributions

SS planned and designed the research project and collected and analysed the data. HMTR assisted in analysing the data using the Institutional Analysis and Development framework. DCM contributed to the development of the methodology and supervised data collection and analysis. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Biographical sketches

Samia Saif is a conservation scientist from Bangladesh. Her research interests include wildlife trade, poaching, local use of wildlife, and human−wildlife conflict. H. M. Tuihedur Rahman's research interests lie in sustainable natural resource management and rural economic development. Douglas Macmillan's research focuses on developing and assessing approaches to integrating biodiversity conservation and management with sustainable livelihoods and lifestyles, with an emphasis on economic incentives for promoting sustainable use of wild resources.